Abstract

Ethanol extracts from developed kimchi condiments (KME, KMEE) and mixtures of sub-ingredients (ME, MEE) showed high nitrite scavenging activity. ME was able to scavenge 89% of total nitrite at 50 mg/mL ME and pH 1.2. The nitrite scavenging abilities of KME and KMEE were significantly higher than in ethanol extract from the control condiment. The inhibitory effects on N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) formation by decrease of salted-fermented fish products (Jeot-gal) and increase of condiments in the composition of kimchi were investigated. The modified kimchi (KM) was prepared with new condiments, which included new sub-ingredients and reduced Jeot-gal. The NDMA and its precursor levels were significantly decreased in KM compared with those in the control kimchi (KC). The KM also obtained higher sensory scores than KC. Therefore, the increase of sub-ingredients and reduction of Jeot-gal in kimchi would be recommended for production of reduced-NDMA kimchi while maintaining or even enhancing flavor profiles.

Keywords: Condiment, Kimchi, N-nitrosodimethylamine, Nitrite, Salted-fermented fish products

Introduction

Kimchi is a Korean fermented vegetable food that has been salted, blended with various sub-ingredients, such as garlic, dried red pepper powder, ginger, green onion, onion, and salted-fermented fish products (Jeot-gal), and fermented for a certain period at ambient temperature [1]. The most common raw material used to prepare kimchi is baechu (Chinese cabbage). Temperature is the most important factor affecting kimchi fermentation, because microorganisms naturally present in the raw materials are the main cause of kimchi fermentation. Nowadays, kimchi is fermented at 13–20 °C for 1–3 days and then stored at −2.0 to 2.0 °C in a Kimchi refrigerator for long-term storage by slow fermentation in Korea.

N-Nitrosamines (NA) can be easily found in air, water, foods, cosmetics, tobacco, and packing materials [2]. N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) as a very toxic NA is a potent carcinogen and is readily formed by the reaction of nitrite with dimethylamine (DMA), a secondary amine [3]. Nitrate reductases in the mouth and various other environments convert nitrate into nitrite [4]. Jeot-gal made from salt-fermented anchovy and salt-fermented shrimp contains a large amount of DMA and biogenic amines, while baechu contains large amounts of nitrate and nitrite [5]. Thus, the possibility of nitrosamine formation in kimchi during fermentation and storage may exist due to the presence of both these ingredients. However, garlic, red pepper, ginger, green onion, and onion are also sub-ingredients in kimchi, and contain NDMA inhibitors such as ascorbic acid, allyl sulfur compounds, and phenolic compounds [3]. Therefore, kimchi contains substances that both promote and inhibit NDMA formation.

NDMA in kimchi has previously been detected [2] and so, in this study, a method was developed to reduce the levels of NDMA and its precursors in kimchi.

Based on the report of Chung et al. [3] that garlic could inhibit NDMA formation and had nitrite-scavenger activity, we hypothesized that the types and amounts of kimchi sub-ingredients (condiments) might affect the amounts of NDMA and its precursors in kimchi. The increase of NDMA inhibitors and decrease of salted-fermented fish products in the new condiments may inhibit NDMA formation. This hypothesis was tested in the present study: firstly, new condiments were developed and used to prepare reduced-NDMA kimchi; and secondly, NDMA and its precursors (nitrate, nitrite, and DMA) in the developed kimchi were analyzed to examine the effects of these new condiments on their contents. In addition, the nitrite-scavenging activity of kimchi condiments and a mixture of sub-ingredients added to the new condiments were examined.

Materials and methods

Preparation of extracts

Korean garlic, ginger, dried red pepper powder, onion, apple, cooked rice, raw red hot pepper, and green onion were purchased from an E-mart in Gwangju, Korea. The mixture (M) in Table 1 was prepared from grinding onion (500 g), apple (200 g), cooked rice (60 g), raw red hot pepper (100 g), and green onion (80 g). The M were dried and ground to fine powder. The powder was extracted three times with 10 vol. of 70% ethanol for 8 h at 80 °C. After filtration, the extract was concentrated using a rotary evaporator (N-1200BV, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan) and then freeze-dried in a lyophilizer (Clean Vac-8, Hanil Science Industrial Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). The kimchi condiments of KC, KM and KME in Table 1 were freeze-dried and ground for 70% ethanol extracts, named KCC, KMC and KMEC.

Table 1.

Composition of kimchi ingredients

| Ingredient (g) | Control (KC)d | KMe | KMEf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salted Chinese cabbage | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Dried red pepper powder | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Garlic | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Ginger | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Green onion | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Sugar | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Salt-fermented anchovy | 2.5 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Salt-fermented shrimp | 2.5 | – | – |

| Ma | – | 14.5 | 8 |

| EMb | – | – | 0.25 |

| Water | 15.5 | – | 6.25 |

| Ec | – | 5 | 5 |

a M: mixture, from grinding a mixture of onion (500 g), apple (200 g), cooked rice (60 g) red hot pepper (raw, 100 g), and green onion (80 g)

bEM: mixture of ethanol extracts, namely garlic ethanol extract (0.1 g/mL), onion ethanol extract (0.18 g/mL), green onion ethanol extract (0.18 g/mL), ginger ethanol extract (0.05 g/mL), and dried red pepper powder (0.25 g/mL)

cE: extract for kimchi condiment, containing dried pollack (50 g), dried anchovy (20 g), dried sea tangles (5 g), and green onion (20 g) extracted with water (1 L) for 1 h at 100 °C

dControl (KC): kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients and Jeot-gal

eKM: kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients with M, E and reduced Jeot-gal

f KME: kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients with 55.2% of the amount of M found in the KM condiment, E, EM, and reduced Jeot-gal

Dried pollack (50 g), dried anchovy (20 g), dried sea tangle (5 g), and green onion (20 g) were extracted with water (1 L) for 1 h at 100 °C, and the resultant extract (E) was used instead of Jeot-gal in the new kimchi condiments for the reduction of secondary amines.

The mixture of ethanol extracts from sub-ingredients (EM) contained garlic ethanol extract (0.1 g/mL), onion ethanol extract (0.18 g/mL), green onion ethanol extract (0.18 g/mL), ginger ethanol extract (0.05 g/mL), and dried red pepper powder ethanol extract (0.25 g/mL). M and EM were used as ingredients in kimchi condiments (Table 1). The 70% ethanol extract of M (ME) and the 70% ethanol extract of 55% of M in first developed condiments and EM (MEE) were used to assess nitrite-scavenging abilities.

Nitrite-scavenging ability of extracts

The nitrite-scavenging abilities of extracts were assessed by the method of Kang et al. [6] and determined by measuring the residual nitrite capacity at an absorbance of 520 nm. Various concentrations of samples (1 mL) were added to 0.1 mM NaNO2 solution (1 mL) and 0.2 M citrate buffer (7 mL; pH 1.2 and pH 4.2, respectively) and then the mixtures were adjusted to pH 1.2 and pH 4.2, respectively, and a final volume of 10 mL. The reaction mixture was incubated in a water bath at 37 °C for 1 h. Acetic acid (5 mL, 2%) and Griess reagent (0.4 mL; a 1:1 ratio of 1% sulfanilic acid and 1% naphthylamine both in 30% acetic acid) were added to the reaction mixture (1 mL) and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Spectrophotometric analysis was performed at 520 nm to determine residual nitrite levels.

Kimchi preparation

Baechu (Chinese cabbage) grown in Pyeongchang, Korea, were cut in half and soaked in a salt solution (10% w/v) for 16 h. The soaked Chinese cabbages were washed three times under running tap water, and drained for 2 h. The ingredients used to prepare the kimchi condiments are listed in Table 1. Kimchi was fermented at 13.5 °C for 2 days and stored at −1.0 °C in a Kimchi refrigerator (RP20H3010HY, Samsung, Seoul, Korea). Kimchi was homogenized in a mixing blender (HMF-3450, Hanil Electric, Seoul, Korea) for subsequent experimentation.

NDMA determination

Homogenized kimchi (30 g) was steam-distilled using the methods of Hotchkiss et al. [7] and Kim et al. [8].

The samples were acidified to pH 1 with sulfuric acid containing sulfamate to prevent artificial nitrosamine formation, and 1.0 ppm NDPA (1 mL) was added as an internal standard. The sample was steam-distilled on a steam generator. The distillate (150 mL) was collected and transferred to a 250-mL flask, to which DCM (60 mL) and sodium chloride (500 mg) were added. The distillate was extracted three times with DCM (180 mL). The combined DCM extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, concentrated to a volume of 3–5 mL in a Kuderna-Danish apparatus, and then evaporated under nitrogen gas to a final volume of 1.0 mL. The concentrated samples were used for GC–MS/MS analysis after filtration through a 0.22-μm filter.

GC–MS/MS analysis was performed using Trace 1310 and TSQ 8000 equipment (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). GC conditions were as follows: column, DB-WAX (60 m × 0.25 mm I.D., 0.25 μm df, Agilent Technologies); injection port temperature, 220 °C; transfer line temperature, 240 °C; ion source temperature, 150 °C; reagent gas, ammonia at a flow rate of 2 mL/min; measurement mode, CI mode; injection volume, 2 μL. The column temperature started at 50 °C, held for 1 min, followed by a 20 °C/min ramp to 120 °C, then a 5 °C/min ramp to 180 °C, held for 4 min, and finally a 25 °C/min ramp to 220 °C held for 5 min. Quantification of NDMA was carried out by analysis of known amounts of internal standard NDPA, which was added to the samples prior to extraction.

Nitrate and nitrite determination

Nitrate analysis

Nitrate was measured using the colorimetric method described by Raikons et al. [9] and Kim et al. [8]. The method was based on nitrate ions reacting with 2,6-dimethylphenol to form a colored product with maximum absorbance at 324 nm.

Briefly, distilled water (22.5 mL) was added to homogenized kimchi (2.5 g), and the mixture was homogenized using a high-speed vortex mixer (Daihan Scientific Co.) for 3 min and extracted using an orbital shaker for 30 min. The sample was then boiled for 60 min at 95–100 °C and cooled immediately in an ice-bath. The sample extract was mixed with potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) trihydrate (0.5 mL) and 2 M ZnSO4 (1 mL). The sample was filtered through Whatman paper No. 1 (Whatman, GE Healthcare UK Limited, Buckinghamshire, UK). The samples (0.4 mL) were mixed with H2SO2–H3PO4 (3 mL, 1:1) and 0.12% 2,6-dimethylphenylacetic acid (0.4 mL). The absorbance of nitrate standard solutions and samples was measured at 324 nm.

Nitrite analysis

Homogenized kimchi (20 g) was mixed with distilled water (25 mL) using a high-speed vortex mixer (VM-10; Daihan Scientific Co., Wonju, Korea) for 10 min. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3000×g for 15 min and the supernatants were used for nitrite analysis. The samples (150 L) were mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (a 1:1 mixture of 0.1% N-naphthylene diamine dihydrochloride in distilled H2O and 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid) and then kept at room temperature for 10 min. The optical density was measured at 540 nm [8].

DMA determination

Homogenized kimchi (25 g) was mixed with 7.5% cold trichloroacetic acid solution (50 mL) using a high-speed vortex mixer (VM-10; Daihan Scientific Co.) for 10 min. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3000×g for 15 min, and the supernatants were neutralized with 1 M NaOH and used to analysis DMA [10]. The copper-dithiocarbamate method of Dyer and Mounsey [11] with slight modifications was used to determine DMA in the samples.

The neutralized supernatant extract (2 mL) was thoroughly mixed for 2 min with 5% CS2 in chloroform (5 mL) and alkaline solution containing 40% NaOH and NH4OH (0.2 mL, 1:1), followed by the addition of 30% acetic acid (1 mL). The mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 min. The chloroform layer was transferred into a screw-capped test tube and mixed with anhydrous sodium sulfate (0.2 g). The optical density was measured at 440 nm.

Monitoring NDMA formation in an artificial digestion system

The simulated saliva and gastric juices were made according to previously described methods [12, 13]. The 20 mL simulated saliva [12] was added to 50 g of homogenized kimchi. The mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 5 min and then 80 mL of simulated gastric juice [13] was added. The mixture was adjusted to pH 2.5 with 3 N HCl and then incubated in 37 °C for 1 h with gentle shaking (100 rpm) and the NDMA and nitrite were detected as the above methods.

Sensory evaluation

Kimchi was evaluated by twenty panelists aged 20–26 years old using a five-point scoring scale (1, worst or weak; 5, best or strong). Panelists evaluated sensory parameters such as flavor, texture, taste, salty taste, sour taste, and overall acceptability.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation averaged from three or twenty values per experiment. Each experiment was performed a minimum of three times. The data was analyzed using the SPSS package (Version 10.0, SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan’s multiple-range test was used to compare the results of the different treatments. The results were considered to have statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Results and discussion

Nitrite-scavenging ability of ME, MEE, and kimchi condiments

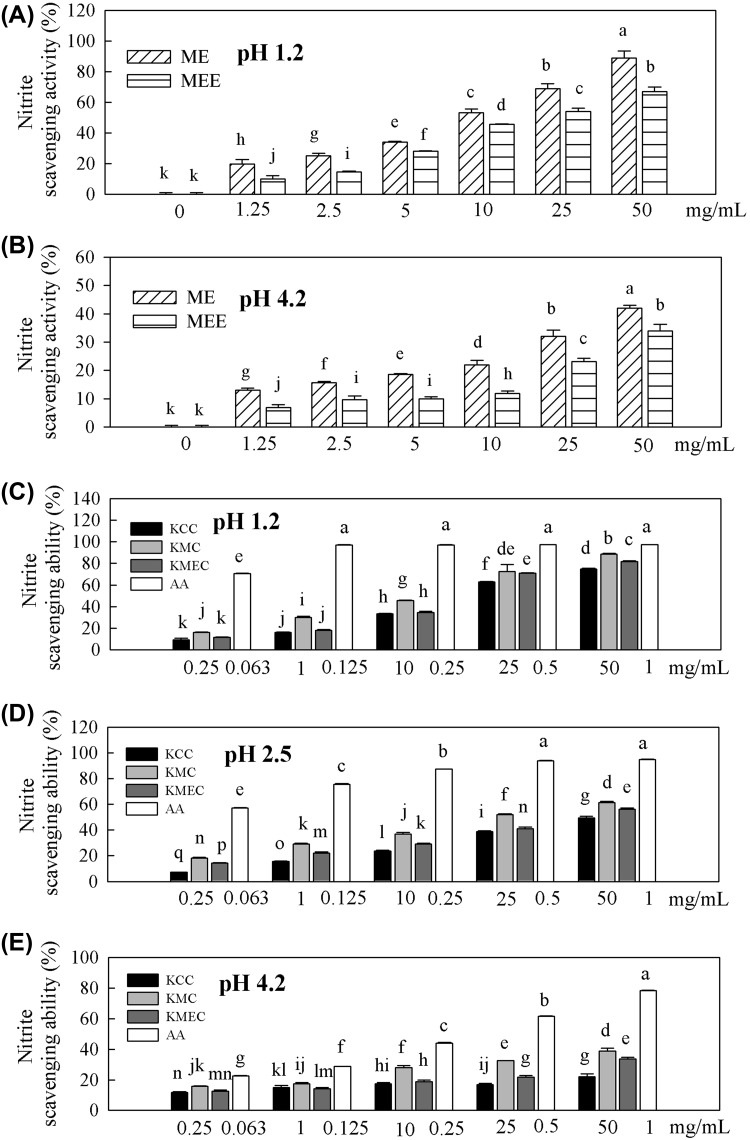

All ME, MEE, and kimchi condiments (KCC, KMC, and KMEC) exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in nitrite-scavenging ability. The scavenging abilities of the kimchi condiments were also higher at pH 1.2 and pH 2.5 than at pH 4.2. At 50 mg/mL and pH 1.2, ME demonstrated the highest nitrite-scavenging ability (89.0%; Fig. 1A) with the nitrite-scavenging ability of ME being higher than that of MEE (Fig. 1A, B). KMC and KMEC had higher nitrate scavenger activity than basic kimchi condiment (KCC) at 25 and 50 mg/mL (Fig. 1C–E). The scavenging abilities of all extracts were significantly lower than those of ascorbic acid as a positive control at the same concentration. The 70% ethanol extracts of kimchi condiment may contain nitrite scavengers such as allyl sulfur compounds and phenolic compounds. However, the nitrite scavengers would have been mixed with other substances in the crude kimchi extracts and, as a result, their scavenging abilities will likely be lower than that of pure ascorbic acid at the same concentration.

Fig. 1.

Nitrite-scavenging abilities of ME, MEE, and kimchi condiments (KCC, KMC, KMEC) at various pH. Nitrite-scavenging abilities are represented by the inhibition percentage of samples compared with the control. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3), and means with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. ME, extract of mixture (M) of onion, apple, cooked rice, raw red hot pepper, and green onion; MEE, extract of 55.2% of M in first developed condiments and a mixture of ethanol extracts of garlic, onion, green onion, ginger, and dried red pepper powder; AA, ascorbic acid; KCC, KMC and KMEC, ingredient without salted Chinese cabbage in Table 1

Nitrite can react with secondary amines under the acidic condition of the stomach (pH 1–3) to form NAs during kimchi digestion [3] and the pH of ripened kimchi is about pH 4. Thus, the nitrite-scavenging ability in this study was tested at pH 1.2, pH 2.5, and pH 4.2.

Red hot pepper (raw) contained high ascorbic acid contents (116 mg/100 g), while garlic, onion, and green onion contained high contents of allyl sulfur compounds [3]. The use of red hot pepper (raw) in M increased ascorbic acid contents in kimchi condiments and it might act as a nitrite scavenger. However, the ME and MEE samples will not contain ascorbic acid due to degradation of the ascorbic acid during extraction and concentration procedures. Thus, the nitrite scavenger ability measured for ME and MEE has little to no contribution from ascorbic acid.

Nitric oxide (NO) is oxidized to form the anions nitrite (NO2 −) and nitrate (NO3 −) [14]. Lundberg et al. [15] demonstrated the importance of low gastric pH for NO formation from nitrite [15]. Indeed, reducing agents such as ascorbic acid and cysteine may facilitate NO formation from nitrite [16]. The nitrite scavenging activity of natural compound and extract was reduced when the pH was increased from pH 1.2 to pH 4.2 because NO formation from nitrite is enhanced under acidic and reducing conditions [16]. The results suggest that bioactive compounds in M and EM may inhibit NDMA formation in kimchi due to their nitrite-scavenging abilities.

Effects of M and EM on NA precursors levels in kimchi

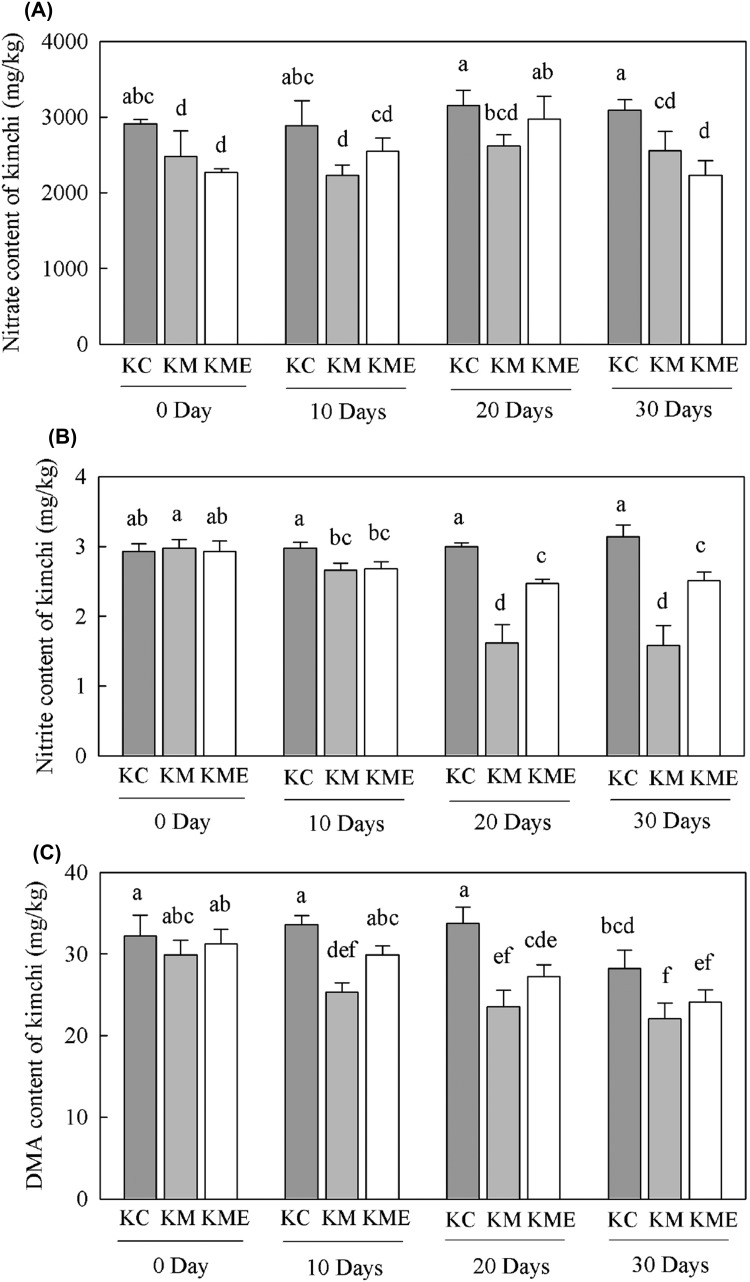

The amount of nitrate in KME increased slightly during 20 days of storage at −1 °C, but the amount of nitrate decreased again at 30 days. In contrast, the nitrate levels in KC and KM at 0, 10, 20, and 30 days of storage showed no statistically significant changes (Fig. 2A). In comparison with KC, the nitrate levels in KM and KME decreased over 0, 10, 20, and 30 days of storage (Fig. 2A). The differences in nitrate level between KM and KME were not statistically significant (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Changes in NDMA precursor levels caused by changing the types and amounts of condiments in kimchi. Values are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3), and means with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. M was prepared by grinding the ingredients of onion, apple, cooked rice, raw red hot pepper, and green onion. EM was a mixture of ethanol extracts of garlic, onion, green onion, ginger, and dried red pepper powder. E was the hot water extract of dried pollack, dried anchovy, dried sea tangles, and green onion. KC, kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients and Jeot-gal; KM, kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients with M, E and reduced Jeot-gal; KME, kimchi containing basic sub-ingredients with 55.2% of the amount of M found in the KM condiment, E, EM, and reduced Jeot-gal; DMA, dimethylamine

KM and KME had the same nitrite levels as KC at 0 day of storage, but lower nitrite levels after 10, 20, and 30 days of storage (Fig. 2B). The nitrite level in KM was lower than in KME after 20 and 30 days of storage (Fig. 2B).

The DMA concentrations in KC, KM, and KME were unchanged after fermentation at 13.5 °C for two days (0 day; Fig. 2C). However, higher DMA levels were obtained in KC than in KM and KME after 20 and 30 days of storage. The DMA level in KME was higher than that of KM after 10 days of storage, but both KM and KME had similarly decreased DMA concentrations after 30 days of storage (Fig. 2C).

KM had a similar or slightly higher effect on decreasing nitrite and DMA levels compared with KME, but not for nitrate concentration. The results suggested that the M and EM might inhibit NDMA formation through an indirect decrease of NDMA precursors.

The LAB species (Lactobacillus sakei, Lactobacillus curvatus, and Lactobacillus brevis) incubation temperature was set at −1 °C for 3 or 7 days after initial incubation at 13.5 °C for 2 days. The viability and growth of the LAB species was then confirmed by culture in MRS agar plates (data not shown). Salt-fermented anchovy and salt-fermented shrimp form about 40% of the total salted-fermented fish products and are commonly used as kimchi ingredients in Korea [17] but the amines contained in these products are precursors of nitrosamine. Kang et al. [18] showed that similar amounts of DMA and NDMA were detected in the salt-fermented anchovy and shrimp. NDMA content was higher in unfermented kimchi with the addition of salt-fermented anchovy than with salt-fermented shrimp but the type of Jeot-gal had no effect on NDMA formation in fermented kimchi [18].

For the production of reduced-NDMA kimchi, we developed two kinds of condiments including basic sub-ingredients from M and EM. Table 1 shows the basic sub-ingredients for making baechu kimchi, such as dried red pepper powder, garlic, ginger, green onion, sugar, and Jeot-gal. M, a mixture of sub-ingredients, was prepared by grinding a mixture of onion, apple, cooked rice, red hot pepper and green onion. M is widely used as one of the kimchi sub-ingredients in Korea to improve its taste. EM was prepared by mixing garlic ethanol extract, onion ethanol extract, green onion ethanol extract, ginger ethanol extract, and dried red pepper powder to increase the inhibitory effects of basic sub-ingredients on NDMA formation in kimchi. Dried pollack, dried anchovy, dried sea tangles, and green onion were extracted with water to furnish an extract, named E. E was used as a sub-ingredient instead of Jeot-gal to reduce the secondary amine content in the kimchi condiment. Developed condiment, 1, contained the basic sub-ingredients without salt-fermented shrimp and with reduced amounts of salt-fermented anchovy + M (14.5 g/100 g salted cabbage) + E (5 g/100 g salted cabbage). Developed condiment 2 contained basic sub-ingredients without salt-fermented shrimp and with a reduced amount of salt-fermented anchovy + EM (0.25 g/100 g salted cabbage) + M (8 g/100 g salted cabbage) + E (5 g/100 g salted cabbage). The developed condiments may contain increased types and amounts of NDMA inhibitors and NDMA precursor scavengers. The developed condiments showed decreased DMA levels (data not shown) because of reduced Jeot-gal content and so the developed condiments may reduce NDMA formation in kimchi. In addition, the developed condiments must result in a nice taste in order to make these methods applicable to the kimchi industry. Kimchi was prepared with developed condiment 1 (KM) or the developed condiment 2 (KME).

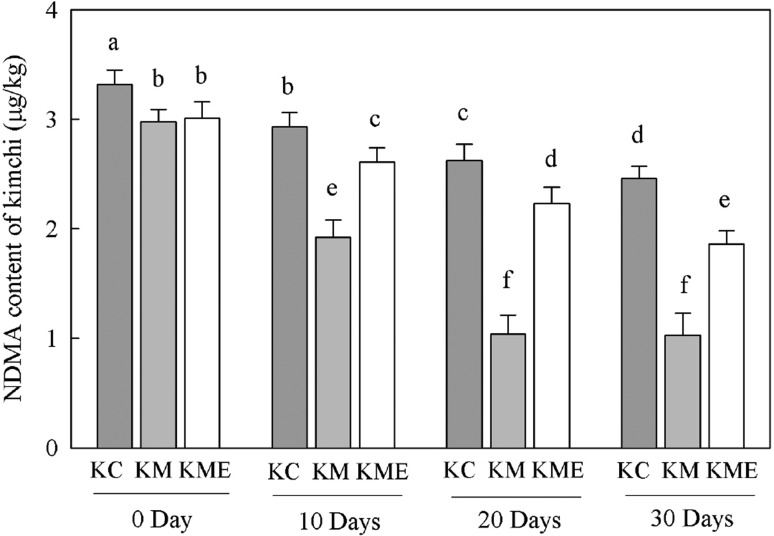

Effects of M and EM on NDMA levels in kimchi

NDMA levels in KM and KME were lower than those of KC throughout the storage period (Fig. 3). The NDMA levels in all samples decreased in a time-dependent manner. KM and KME significantly reduced NDMA concentrations after 30 days of storage, by 65.4 and 38.2%, respectively, compared with KC.

Fig. 3.

Changes in NDMA levels caused by changing the types and amounts of condiments in kimchi. The values are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 3), and means with different letters are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. See Fig. 2 for abbreviations

Kimchi is a side dish that is eaten daily by Koreans; since NDMA is known to be present in kimchi, it is important to find a way to reduce its concentration. M and EM may include many NDMA inhibitors, and changes in the amounts and types of NDMA inhibitors, such as ascorbic acid, allyl sulfur compounds, and phenolic compounds, present in kimchi might change the levels of NDMA and its precursors (nitrate, nitrite, and DMA) in kimchi during fermentation and storage.

Of all nitrosamines, only NDMA was detected in the tested kimchi samples. Park et al. [2] reported that NDMA, NDEA, NDBA, and NPIP were detected in kimchi, but Kim et al. [19] reported only the detection of NDMA in kimchi, in agreement with the present study.

The concentration of NDMA and its precursors (nitrate, nitrite and DMA) in KM and KME were lower than in KC, while KM was shown to have a larger effect on decreasing the concentration of NDMA and its precursors than those of KME.

Chung et al. [3] and Choi et al. [13] reported that garlic, strawberries, and kale effectively reduced the exogenous and endogenous formation of NDMA and suggested that allyl sulfur compounds, ascorbic acid, and phenolic compounds in garlic, strawberries, and kale might act as nitrite scavengers. In addition, Lee et al. [20] demonstrated that the reactions of flavonoids with nitrous acid protect against the formation of NA.

Kang’s study [18] investigated the effects of the amount and type of Jeot-gal on NDMA formation in kimchi and found it was increased by increased use of Jeot-gal. Their study suggested that Jeot-gal was the major cause of NDMA formation in kimchi and those results were used to provide a scientific basis on which to perform this study. In this study, we developed a substitute to Jeot-gal and attempted to develop a kimchi formulation, which can be produced industrially and commercialized. Impact of the new formulation on taste as well as effectiveness in reducing of NDMA content was evaluated and achieved by decreasing proportions of Jeot-gal and increasing that of kimchi condiments.

The reduction of salted-fermented fish products in the kimchi condiments of KM and KME may reduce NDMA formation in kimchi during storage. The technology developed in this study for production of reduced-NDMA kimchi does not require new equipment or specialist training. The price of the reduced-NDMA kimchi will increase slightly due to the increased use of more expensive kimchi condiments, increased use of sub-ingredients and reduction in Jeot-gal content. However, the modified components in kimchi condiments would be recommended for production of reduced-NDMA kimchi in the kimchi industry because of the associated health benefits.

Change in concentration of NDMA and nitrite in kimchi under gastric digestion

We studied the amounts of NDMA formation and nitrite after the incubation of kimchi (KC, KM, and KME) with simulated saliva and gastric juice. The NDMA and nitrite amounts in KM were significantly decreased compared to the KC (Table 2).

Table 2.

The contents of nitrite and NDMA after simulated gastric digestion of 20 day-fermented kimchi

| Kimchi groups | NDMA (μg/kg) and nitrite (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrite | NDMA | |

| Control (KC) | 0.5 ± 0.1a | 1.5 ± 0.1a |

| KM | 0.2 ± 0.1c | 1.1 ± 0.2b |

| KME | 0.3 ± 0.1b | 1.3 ± 0.0ab |

The values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3); means with different letters in the same column are significantly different from each other (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. Abbreviations: see Table 1

In the model system of human consumption, the inhibition of NDMA formation might be mainly due to ascorbic acid, phenolic compounds and allyl sulfur compounds in kimchi [3, 8] and the decrease of salted-fermented fish products in kimchi were decreased the NDMA level in KM during artificial digestion.

Sensory evaluation of KM and KME

As shown in Table 3, KM had higher sensory scores for taste, sour taste, and overall acceptability than KC after 10 days of storage, while the opposite trend was observed for salty taste. KM and KME had lower sensory scores in the salty test than KC after 0 and 10 days of storage. The scores for flavor, texture, taste, and overall acceptability decreased during long-term storage, while the score for sour taste increased.

Table 3.

Sensory evaluation of kimchi during storage for 30 days

| Kimchi | Days | Flavor | Texture | Taste | Salty taste | Sour taste | Overall acceptability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KC | 0 | 3.7 ± 0.3a | 3.8 ± 0.3a | 3.9 ± 0.3ab | 3.5 ± 0.3a | 1.2 ± 0.3d | 3.8 ± 0.2b |

| 10 | 3.7 ± 0.2a | 3.6 ± 0.4a | 3.3 ± 0.3b | 3.5 ± 0.6a | 2.1 ± 0.1c | 3.4 ± 0.2c | |

| 20 | 2.9 ± 0.5b | 3.1 ± 0.5b | 2.9 ± 0.5c | 3.6 ± 0.5a | 2.3 ± 0.2c | 3.1 ± 0.3c | |

| 30 | 3.0 ± 0.5b | 3.1 ± 0.1b | 3.1 ± 0.7bc | 3.5 ± 0.7a | 2.6 ± 0.2b | 3.1 ± 0.4c | |

| KM | 0 | 3.8 ± 0.4a | 3.7 ± 0.4a | 4.2 ± 0.3a | 2.6 ± 0.2c | 1.5 ± 0.4d | 4.3 ± 0.2a |

| 10 | 3.8 ± 0.6a | 3.7 ± 0.5a | 4.1 ± 0.3a | 2.5 ± 0.2c | 2.5 ± 0.1b | 4.2 ± 0.4a | |

| 20 | 3.0 ± 0.5b | 3.2 ± 0.4ab | 3.2 ± 0.5bc | 3.1 ± 0.4ab | 2.5 ± 0.2bc | 3.5 ± 0.5bc | |

| 30 | 3.3 ± 0.5ab | 3.2 ± 0.3ab | 3.3 ± 0.5bc | 3.0 ± 0.5ab | 2.8 ± 0.4ab | 3.7 ± 0.3bc | |

| KME | 0 | 3.7 ± 0.2a | 3.8 ± 0.4a | 4.1 ± 0.4a | 2.6 ± 0.2c | 1.3 ± 0.4d | 3.8 ± 0.2b |

| 10 | 3.5 ± 0.2ab | 3.5 ± 0.4a | 3.5 ± 0.4ab | 2.6 ± 0.2c | 2.2 ± 0.1c | 3.8 ± 0.2b | |

| 20 | 3.0 ± 0.5b | 2.9 ± 0.5b | 3.1 ± 0.5bc | 3.1 ± 0.6ab | 2.6 ± 0.2b | 3.4 ± 0.5bc | |

| 30 | 3.4 ± 0.5ab | 2.6 ± 0.7b | 3.1 ± 0.9bc | 3.3 ± 0.6a | 3.0 ± 0.2a | 3.3 ± 0.5bc |

Values are expressed as the mean ± SD (n = 20), and means with different letters are significantly different from each other in the same items (p < 0.05), as determined by Duncan’s multiple range test. See Table 1 for abbreviations

Microorganisms naturally present in the raw materials, which contain numerous microflora including lactic acid bacteria, are the main cause of kimchi fermentation. The kimchi fermentation process has several stages based on the change in pH caused by lactic acid bacteria that continuously produces acid [21] and so sour taste may increase during storage.

The KM obtained higher sensory scores in taste and overall acceptability than KC, confirming that KM produces palatable kimchi. The decrease in salty taste scores for KM and KME might be caused by the lower Jeot-gal content. The sensory scores for flavor, texture, taste, and overall acceptability decreased with increasing storage periods. The results suggested that young people in Korea might prefer less fermented kimchi than fully fermented kimchi. The overall consumption of kimchi by Koreans is decreasing and falling even more dramatically amongst young people [22]. Therefore, sensory tests were performed on young people to find kimchi that young people prefer.

M and EM cause a decrease in the concentration of NDMA and nitrite in kimchi through nitrite-scavenging activity. These results suggested that reduction of Jeot-gal and increase of kimchi sub-ingredients could produce reduced-NDMA kimchi with a pleasant taste. In addition, detailed characterization of the individual bioactive components as NDMA inhibitors in kimchi is needed.

Acknowledgements

This research was supports by a grant from the World Institute of Kimchi (KE1701-5), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jeong SH, Lee HJ, Jung JY, Lee SH, Seo HY, Park WS, Jeon CO. Effects of red pepper powder on microbial communities and metabolites during kimchi fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013;160:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park JE, Seo JE, Lee JY, Kwon HJ. Distribution of seven N-nitrosamines in food. Toxicol. Res. 2015;31:279–288. doi: 10.5487/TR.2015.31.3.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung MJ, Lee SH, Sung NJ. Inhibitory effect of whole strawberries, garlic juice or kale juice on endogenous formation of N-nitrosodimethylamine in humans. Cancer Lett. 2002;182:1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lidder S, Webb AJ. Vascular effect of dietary nitrate (as found in green leafy vegetables and beet root) via the nitrate–nitrite–nitric oxide pathway. Brit. J. Clin. Pharmaco. 2013;75:677–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang KH, Lee SJ, Ha ES, Sung NJ, Kim JG, Kim SH, Kim SH, Chung MJ. Effects of nitrite and nitrate contents of Chinese cabbage on formation of N-nitrosodimethylamine during storage of kimchi. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;45:117–125. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2016.45.1.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang KH, Park SY, Kwon KH, Lim HK, Kim SH, Kim JG, Chung MJ. Antioxidant activity and inhibitory effect against oxidative neuronal cell death of kimchi containing a mixture of wild vegetables with nitrite scavenging activity. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015;44:1458–1469. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2015.44.10.1458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotchkiss JH, Barbour JF, Scanlan RA. Analysis of malted barley for N-nitrosodimethylamine. J. Agr. Food Chem. 1980;28:678–680. doi: 10.1021/jf60229a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SH, Kang KH, Kim SH, Lee SH, Lee SH, Ha ES, Sung NJ, Kim JG, Chung MJ. Lactic acid bacteria directly degrade N-nitrosodimethylamine and increase the nitrite-scavenging ability in kimchi. Food Control. 2017;71:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.06.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raikos N, Fytianos K, Samara C, Samanidou V. Comparative study of different techniques for nitrate determination in environmental water samples. Fresenius Z. Anal. Chem. 1988;331:495–498. doi: 10.1007/BF00467037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gou J, Lee HY, Ahn J. Effect of high pressure processing on the quality of squid (Todarodes pacificus) during refrigerated storage. Food Chem. 2010;119:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyer WJ, Mounsey YA. Amines in fish muscle II. Development of trimethylamine and other amines. J. Fish Res. Board of Can. 1945;6:359–367. doi: 10.1139/f42-043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim JD, Lee OH, Lee JS, Jung HY, Kim BK, Park KY. Safety effects against nitrite and nitrosamine as well as anti-mutagenic potentials of kale and Angelica keiskei vegetable juices. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014;43:1207–1216. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2014.43.8.1207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi SY, Chung MJ, Lee SJ, Shin JH, Sung NJ. N-nitrosamine inhibition by strawberry, garlic, kale, and the effects of nitrite-scavenging and N-nitrosamine formation by functional compounds in strawberry and garlic. Food Control. 2007;18:485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2005.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moncada S, Palmer R, Higgs E. Nitric oxide: physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 1991;43:109–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Lundberg JM, Alving K. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: measurements in expelled air. Gut. 1994;35:1543–1546. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.11.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samouilov A, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL. Evaluation of the magnitude and rate of nitric oxide production from nitrite in biological systems. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;357:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim YM. Present status and prospect of fermented seafood industry in Korea. Food Sci. Ind. 2008;41:16–33. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang KH, Kim SH, Kim SH, Kim JG, Sung NJ, Lee SJ, Chung MJ. Effects of amount and type of Jeotgal, a traditional Korean salted and fermented seafood, on N-Nitrosodimethylamine formation during storage of kimchi. J. Korean Soc. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;45:1302–1309. doi: 10.3746/jkfn.2016.45.9.1302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KR, Shin JH, Lee SJ, Kang HH, Kim HS, Sung NJ. The formation of N-nitrosamine in kimchi and salt-fermented fish under simulated gastric digestion. J. Food Hyg. Saf. 2002;17:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SYH, Munerol B, Pollard S, Youdim KA, Pannala AS, Kuhnle GGC, Debnam ES, Rice-Evans C, Spencer JPE. The reaction of flavanols with nitrous acid protects against N-nitrosamine formation and leads to the formation of nitroso derivatives which inhibit cancer cell growth. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2006;40:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mheen TI, Kwon TW. Effect of temperature and salt concentration on kimchi fermentation. Kor. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1984;16:443–450. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park JH, Lee HJ. Shifts in kimchi consumption between 2005 and 2015 by region and income level in the Korean population: Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (2005, 2015) Korean J. Community Nutr. 2017;22:145–158. doi: 10.5720/kjcn.2017.22.2.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]