Abstract

Ginseng and red ginseng are popular as functional foods in Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, and China. They possess various pharmacologic effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, anti-obesity, and anti-viral activities. Ginsenosides are a class of pharmacologically active components in ginseng and red ginseng. Major ginsenosides are converted to minor ginsenosides, which have better bioavailability and cellular uptake, by microorganisms and enzymes. Studies have shown that ginseng and red ginseng can affect the physicochemical and sensory properties, ginsenosides content, and functional properties of dairy products. In addition, lactic acid bacteria in dairy products can convert into minor ginsenosides and ginseng and red ginseng improve functionality of products. This review will discuss the characteristics of ginseng and red ginseng, and their bioconversion, functionality, and application in dairy products.

Keywords: Ginseng, Red ginseng, Ginsenoside, Bioconversion, Dairy product

Introduction

The consumption of healthy foods has risen following an increase in average income and many consumers purchase various functional products including vitamins, probiotics, and ginseng-related products [1]. Ginseng and red ginseng are popular functional foods in Korea. Especially, sales of red ginseng have risen steadily [1].

In Korea, ginseng is commercially distributed as four types, namely; fresh ginseng, white ginseng, Taekuksam, and red ginseng, and these are manufactured using different methods [2]. Fresh ginseng has high water content and coexists with soil microorganisms [3]. White ginseng is produced by sun-drying fresh ginseng [4]. Taekuksam is produced by blanching in water and drying [2]. Red ginseng is produced by repeatedly steaming and air-drying fresh ginseng [5]. Four types of ginseng were manufactured to use ginseng root. White ginseng was referred to as ginseng in oriental medicine books and red ginseng has a long history of production development and export to other countries [6]. Ginseng and red ginseng are delivered in diverse forms including natural root, powder, tablet, tea, extract, and beverage [7, 8]. The major companies that manufacture red ginseng products have emphasized functionality and manufacture fermented red ginseng for the satisfaction of consumer needs and the expansion of ginseng sales in the domestic and foreign functional food markets [9, 10].

According to a report by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, the production of milk has remained steady in recent years, while the production and consumption of milk powder, fermented milk, and soy milk have increased and the domestic milk powder were exported to China [11]. Dairy companies have produced diverse functional dairy products including organic, reduced fat, and artificial-additives-free, reduced sodium and sugar, lactose-free, probiotics-supplemented, and nutrient-, calcium-, or protein-fortified products [11, 12]. This review aims to introduce the characteristics of ginseng and red ginseng and explore their potential applications in dairy products for Korean consumers.

Ginseng and red ginseng

Characteristics

The term ginseng refers to the dried root of several plant species in the genus Panax (family Araliaceae) that have a history of medicinal use spanning over 5000 years [13]. The ginseng species are Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolius, Panax notoginseng, and Panax japonicus [13]. P. ginseng, commonly called Korean ginseng, is an important herb in East Asia. This species has a short root and possesses antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, antidiabetic, and anti-stress effects [14]. P. quinquefolius, commonly called American ginseng, is used in North America and is resistant to spoilage. It has antioxidative, antiulceric, and neuroprotective effects [14]. P. notoginseng, commonly called Chinese ginseng, is valuable in Japan and southern areas of China, and may prevent rheumatoid arthritis and decrease cholesterol [14]. P. japonicus is a traditional medicinal herb in the southwest region of China, and its use was recorded in a book of traditional Chinese medicine published in 1765. P. japonicus may help to prevent a decrease in haematopoietic activity and inhibit tumor growth [15]. The chemical constituents of ginseng are carbohydrates, amino acids, minerals, lipids, proteins, and bioactive components such as ginsenosides, acidic polysaccharides, and polyacetylenes [14]. Polyacetylenes are unsaturated triple-bonded polyalcohols that represent the main nonpolar active constituents of ginseng [16]. Polyacetylenes have lipophilic properties and include panaxynol, panaxydol, panaxydiol, panaxytriol, panaxacol, panaxyne epoxide, and ginsenoyne A-K [16]. They have anticancer and antioxidant effects that are attributed panaxydol, panaxynol, and panaxytriol [17]. The acidic polysaccharides of ginseng comprise of galacturonic acid, glucuronic acid and mannuronic acid, which have molecular weights over 15,000 Da [18, 19]. Acidic polysaccharides have pharmaceutical activities including anticoagulating and anticancer effects [19, 20].

Red ginseng was reported in the Annals of King Jeongjo, and the method for processing red ginseng was introduced in Goryeo Dogyeong [21]. An overview of the process is as follows; fresh ginseng is selected, the dirt is removed, and the root is washed with clean water. The washed ginseng is steamed for 1–3 h at 90–98 °C. Then it is dried with hot air and laid in the sun until its moisture content drops to between 15 and 18% [21]. The production process, which includes significant heating, increases the amounts of total sugar, reducing sugar, and polyphenols in red ginseng [22]. The amounts of arginine-fructose-glucose and arginine-fructose increase during the steaming and drying processes. In addition, the color and maltol content of red ginseng are changed by the steaming process [23]. The bioactive components such as ginsenosides, acidic polysaccharides, and polyacetylenes changed during the production process of red ginseng. The amount of acidic polysaccharides in red ginseng is three times higher than that in white ginseng because of the degradation of sugar components [21]. The ginsenoside content in red ginseng was increased during the production process especially, that of ginsenosides Rh1, Rg2, Rg3, Rk3, Rh4, Rk1, and Rg5 because of deglycosylation at the C-20 position [23].

Health functionality

Previous studies have indicated that ginseng and red ginseng may contribute to the prevention of diseases through diverse mechanisms such as antiobesity, antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-stress, antiviral, and anticancer effects.

Ginseng increased the plasma adiponectin level and inhibited fat accumulation and adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells [24]. Ginseng exhibited electron-donating activity and inhibited nitric oxide production and NF-кB activity [25]. Ginseng alleviated the degradation of immune organs in the rat because it reduced the secretion of corticosterone [26]. Ginseng increased the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase in the skin and liver, and reduced acanthosis and tumor nets [27].

Red ginseng inhibited the growth of lung carcinoma cells, reduced the activities of rennin and angiotensin-converting enzyme, decreased the angiotensin II levels, activated nitric oxide production, and caused a reduction of arterial blood pressure [28, 29]. Red ginseng inhibited the synthesis of cholesterol and HMG-CoA reductase activity [30]. It reduced behavioral impairment, protected dopaminergic neurons, prevented oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, and inhibited apoptosis via the upregulation of PI3 K/Akt signals in brain cells under oxidative stress [31, 32]. Red ginseng ameliorated the decline of learning potential and memory retention in aged mice by showing that red ginseng extract improved the activities of the antioxidant enzyme Nrf2 and HO-1 [33]. Red ginseng was effective against diverse virus types including influenza virus and norovirus [5]. Red ginseng also acted as a mucosal adjuvant against influenza virus A/PR8 during viral infection and improved H1N1 vaccine efficacy by increasing anti-influenza virus A-specific IgG titers and survival rates [5]. Pretreatment with red ginseng and ginsenosides induced antiviral protein in feline calicivirus-infected Crandell-Reese feline kidney [5]. Red ginseng inhibited obesity, adipocyte hypertrophy, and adipose inflammation in high fat diet-fed ovariectomized mice [34]. It has been demonstrated that the pharmaceutical effects of ginseng and red ginseng can be attributed to their ginsenoside content.

Ginsenosides

Analysis and classification

Ginsenosides are characteristic components of ginseng that have been reported to show pharmaceutical effect, and more than 50 ginsenosides have been identified using methods including thin layer chromatography (TLC), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography (GC), capillary electrophoresis, near infrared spectroscopy, and enzyme immunoassay [21, 35]. TLC is a simple and easy-to-operate analytical technique, and HPLC is the most common analytical method, so TLC and HPLC are usually used to together identify ginsenosides [36, 37].

Ginsenosides are categorized based upon the positions of their hydroxyl groups and/or double bonds [38]. Ginsenosides are classified into two major types, dammarane and oleanane. The dammarane-type ginsenosides are divided into three groups: protopanaxadiol (PPD), protopanaxatriol (PPT), and ocotillol types. The oleanane group contains oleanolic acid type [39]. The PPD type consists of an aglycone with a dammarane skeleton and sugar moieties attached to the β-OH at C-3 and/or C-20 and includes ginsenosides Ra1, Ra2, Ra3, Rb1, Rb2, Rb3, Rc, Rd, Rg3, Rh2, F2, and compound K [39]. The PPT type consists of an aglycone with a dammarane skeleton and sugar moieties attached to the α-OH at C-6 and/or β-OH at C-20 and includes ginsenoside Re, Rf, Rg1, Rg2, Rh1, and F1 [39]. The ocotillol type has an epoxy ring at C-20 and includes majonoside R2 and pseudoginsenoside F11. The oleanane group consists of a pentacyclic structure with aglycone oleanolic acid and includes only ginsenoside RO [39].

Bioconversion using enzymes and microorganisms

Minor ginsenosides have more pharmaceutical activity than major ginsenosides because of their smaller size, higher bioavailability, and better permeability across cell membranes [40]. Therefore, several research groups have studied the deglycosylation of ginsenosides. The methods for converting major ginsenosides to minor ginsenosides are mild acid or alkali hydrolysis, heating, microbial, and enzymatic action [40–42]. Several studies have reported that major ginsenosides can be deglycosylated by digestive enzymes or microorganisms (Table 1). Such biotransformation processes have the advantages of high specificity and selectivity, and a low environmental impact [40].

Table 1.

The pathway of ginsenosides by enzymatic and microbial bioconversion

| Materials | Pathway of bioconversion (References) | Materials | Pathway of bioconversion (References) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | |||

| β-Glucosidase | Rb1 → Rd → compound K [42] | Cellulase 12T | Rb1 → Rd → Rg3 [44] |

| β-Glycosidase | Rb1 or Rb2 → Rd → F2 → compound K [43] Rc → compound Mc → compound K [43] |

Cellulase KN | Re → Rg1 → F1 [45] |

| Microorganism | |||

| Bifidobacterium sp. Int57 | Rb2, Rc → Rd [46] |

A. usamii

KCTC 6954 |

Rb1 → Rd → F2 → compound K [53] |

| Bifidobacterium sp. SH5 | Rb1, Rb2, Rc → Rd [46] |

A. niger

KCCM 11239 |

Rb1 → Rd → Rg3 [54, 55] Rb1 → Rd → F2 [54] |

| Leu. paramesenteroids a | Rb1 → Rd → F2 → Rh2 [46] | A. niger g.848 | Rb1 → Rd → F2 → compound K [56] |

| L. plantarum | Rb1 → Rd → Rg3 [47] | P. bainier | Rb1 → Rd → F2 → compound K [58] |

| Leu. mesenteroides DC102 | Rb1 → gypenoside XVII/Rd → F2 → compound K [49] | P. bainier sp. 229 | Rb1 → gypenoside XYII/Rd → F2 → compound K [59] Rb1 → Rd → Rg3 → Rh2 [59] |

| L. rhamnosus GG | Rb1 → Rd [50] | P. bainier 229-7 | Rb1 → Rd [60] |

| Lc. lactis | Rb1 → Rd → F2 [51] | ||

a L., Lactobacillus; Lc., Lactococcus; Leu., Leuconostoc; A., Aspergillus; P., Paecilomyces

Enzymatic bioconversion

Enzymatic transformation is one of the various methods used for converting major ginsenosides into minor ginsenosides. β-Glucosidase, β-glycosidase, pectinase, cellulase, and naringinase are used commercially for this purpose [42–45]. β-Glucosidase and β-glycosidase converted ginsenoside Rb1 to ginsenoside compound K, and pectinase reacted with ginseng to produce ginsenoside compound K [42, 43]. Cellulase generated ginsenoside Rg3 in white ginseng extract, and cellulase mixed with naringinase transformed ginsenosides Re and Rg1 into ginsenoside F1 [44, 45].

Microbial bioconversion

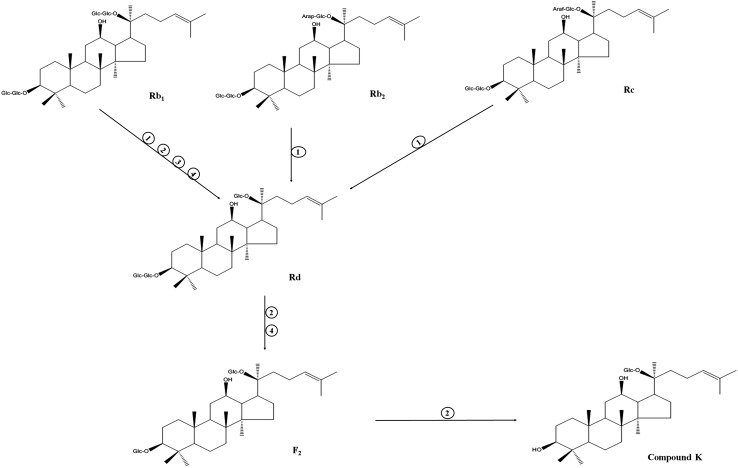

Microorganisms produce various enzymes including β-glucosidase, β-glycosidase, and β-galactosidase for the transformation of ginsenosides [42, 43]. Lactic acid bacteria including Bifidobacterium bifidum, B. longum, Bifidobacterium sp., Leuconostoc paramesenteroides, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides, Lactobacillus delbrueckii, L. plantarum, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, L. fermentum, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, L. rhamnosus, and Lactococcus lactis participated in biotransformation and produced β-glucosidase [46–51]. Lactic acid bacteria convert major ginsenosides Rb1 or Rd into minor ginsenosides Rg3, F2, Rh2, and compound K (Fig. 1). Fungi also produced β-glucosidase and transformed major ginsenosides into minor ginsenosides [52–57]. Aspergillus sp. hydrolyzed PPD type-ginsenosides, especially, A. usamii, A. niger, and A. oryzae and produced ginsenosides Rg3, compound K, and small sized ginsenosides [52–57]. Paecilomyces bainier produced β-glucosidase and hydrolyzed ginsenoside Rb1 into ginsenosides Rd, F2, and compound K [58–60].

Fig. 1.

The bioconversion pathway of ginsenosides by starter cultures in dairy products [40, 46, 49–51]. 1 Bifidobacterium sp.; 2 Leuconostoc mesenteroides; 3 Lactobacillus rhamnosus; 4 Lactococcus lactis

Improved health functionality through bioconversion

Ginsenosides are the main bioactive constituents in ginseng and have diverse pharmaceutical effects (Table 2). Ginsenoside Rb1, of the PPD type, has been found to exert anti-apoptotic effect via the stimulation of estrogen receptor, appeared to cause the downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and had a protective effect against oxidative stress induced by tetra-butylhydroperoxide [61]. Ginsenoside Rb2 has an anti-osteoporosis effect as shown by its ability to protect osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells against cytotoxicity and osteoblast dysfunction induced by H2O2 [62]. Ginsenoside Rb3 inhibited the isoproterenol-induced increase in malondialdehyde levels, increased the activities of creatine kinase and lactate dehydrogenase, and attenuated myocardial ischemia injury induced by isoproterenol and impaired heart function [63]. Ginsenoside Rc reduced the inflammatory response by suppressing the TBK1/IRF-3 and p38/ATF-2 pathways [64]. Ginsenoside Rd exhibited a neuroprotective effect and a protective effect against from lipid peroxidation, and increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes [65, 66]. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibited the growth of colon cancer and breast cancer cell, and suppressed melanin synthesis and tyrosinase activity [67–69]. Ginsenoside Rh2 had anti-obesity, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antiviral activities [70–73]. Ginsenoside F2 induced the apoptosis in breast cancer stem cells, inhibited adipogenesis process, and suppressed IL-17A production [74–76]. Ginsenoside compound K inhibited histamine release, enhanced insulin secretion, increased the level of type I procollagen and decreased MMP-1 activity [42].

Table 2.

The main functionalities of ginsenosides

| Ginsenoside | Functionality | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protopanaxadiol (PPD)-type | Rb1 | Anti-apoptotic effect, anti-inflammatory effect, antioxidant effect | [61] |

| Rb2 | Anti-osteoporosis effect | [62] | |

| Rb3 | Effect against myocardial injury and heart function impairment | [63] | |

| Rc | Anti-inflammatory effect | [64] | |

| Rd | Neuroprotective effect, anti-inflammatory effect | [65, 66] | |

| Rg3 | Anti-cancer effect, anti-melanogenic effect | [67–69] | |

| Rh2 | Anti-obesity effect, anti-inflammatory effect, anti-cancer effect, anti-viral effect | [70–73] | |

| F2 | Anti-cancer effect, anti-obesity effect, inhibition effect of skin inflammation | [74–76] | |

| Compound K | Anti-allergic effect, anti-diabetic effect, anti-aging effect | [42] | |

| Protopanaxatriol (PPT)-type | Re | Anti-arrhythmic effect, reduction of insulin resistance | [77, 78] |

| Rf | Inhibition of tolerance to analgesia | [79] | |

| Rg1 | Anti-depressant effect, anti-inflammatory effect, neuroprotective effect, protection against sepsis-associated encephalopathy | [80–83] | |

| Rg2 | Neuroprotective effect, anti-apoptosis effect, protective effect against UV-B | [84–86] | |

| Rh1 | Inhibitory effect of atopic dermatitis, anti-metastatic effect | [87, 88] | |

| F1 | Protective effect against UV-B | [89] | |

| Ocotillol type | Pseudoginsenoside F11 | Protective effect against neurotoxicity, anti-amnesic effect, anti-neuroinflammatory effect | [90–92] |

| Oleanolic acid type | Ro | anti-inflammatory effect, anti-apoptosis effect | [93, 94] |

Ginsenoside Re of the PPT type exhibited an antiarrhythmic effect and insulin sensitivity, and promoted the uptake and disposal of glucose in 3T3-L1 adipocytes [77, 78]. Ginsenoside Rf enhanced U50-induced analgesia and inhibited tolerance to analgesia [79]. Ginsenoside Rg1 ameliorated depression-like behavior, showed neuroprotective action, alleviated hepatic histological abnormality in mice with CCl4-induced liver injury, and reduced inflammatory mediators. It also protected dopaminergic neurons from 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced toxicity and brain damage from sepsis by inhibiting cerebral inflammation and neuron loss in the hippocampus [80–83]. Ginsenoside Rg2 had a protective effect against glutamate-induced neuronal injury and the formation of Aβ in PC12 cells, protected memory functions against impairment induced by cerebral ischemia–reperfusion and the neuronal apoptosis, and attenuated the UV-B-induced promatrix metalloproteinase-2 gelatinolytic activity and protein level [84–86]. Ginsenoside Rh1 inhibited the infiltration of inflammatory cells into skin lesions and MMP-1 transcriptional activity and decreased the concentrations of IgE and IL-6 in serum, expression and stability of Ap-1 dimer, c-Fos, and c-Jun by inhibiting the activation of JNK and ERK 1/2 in HepG2 cells [87, 88]. Ginsenoside F1 had a protective effect against UVB-induced apoptosis in HaCaT cells [89].

Pseudoginsenoside F11, an ocotillol type-ginsenosides, antagonized methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in mice and shortened the prolonged latency induced by methamphetamine [90]. Pseudoginsenoside F11 rescued the cognitive impairment in mice treated with Aβ1-42, and inhibited the neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in N9 microglia via inhibition of TLR4-mediated TAK1/IKK/NF-κB, MAPK, and PI3 K/Akt pathways [91, 92].

Ginsenoside Ro, the oleanolic acid type, downregulated inflammatory cytokines including nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 that are induced by LPS, inhibited caspase 3 activity, and alleviated IL-1β-induced inflammation and matrix degradation [93, 94].

Application in dairy products

Milk fortified with ginseng and red ginseng

Milk of cows, buffaloes, goats, and sheep is used for human consumption directly and as various dairy products [95]. Milk consists of water, lactose, proteins, lipids, organic acids, minerals, vitamins, salts (Ca, Mg, K, and Na), and enzymes (lysozyme, oxidoreductase, phosphatase, lipolytic enzyme, and proteinase) [95, 96]. Raw milk is processed via several steps including storage, cleaning, homogenization, fat standardization, heat treatment, cooling, and filling/packing [96].

Milk products fortified with ginseng or red ginseng have been developed and information about them is available through published research, conference abstracts, and patent applications. A method for extracting saponin from ginseng-supplemented milk has been optimized as a quantitative method of indicating the presence of ginseng in milk [97]. The optimized temperature, time, and cooling temperature were 86 °C, 2 h 50 min, and 4 °C, respectively, for the extraction of total saponin from ginseng milk [97]. A milk beverage fortified with 0.1% American ginseng extract was evaluated for its ginsenoside content using HPLC and sensory tests including a quantitative descriptive analysis and a consumer study [98]. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb2, Rc, Rd, Re, and Rg1 were detected in in the American ginseng-supplemented milk beverage [98]. Sensory tests demonstrated that the American ginseng affected flavor attributes, increased the bitterness and metallic taste of the product, and changed its color [98]. Those findings demonstrated that the dairy industry could potentially develop ginseng milk, using sensory tests to achieve consumer satisfaction.

Red ginseng-supplemented milk products have been made with red ginseng alone or red ginseng mixed with lactoferrin, cyclodextrin, and black garlic [99–102]. Bae et al. [99] demonstrated the possibility of red ginseng milk through color, stability, and consumer acceptability. Park et al. [100] developed milk fortified with red ginseng extract (0.3–1.5%) and cyclodextrin (α, β, and γ). Cyclodextrin, a banana extract, and a flavoring agent were used to reduce the bitterness of red ginseng in accordance with the preferences the children, the elderly, and the infirm [100]. Chung et al. [101] made a red ginseng milk beverage fortified with black garlic extract. They added black garlic extract (0.1–20%), red ginseng extract (0.001–10%), and gintonin (0.001–10%), and conducted a sensory evaluation with consumers. Jung et al. [102] made red ginseng milk and determined its physicochemical properties and antioxidant capacity. The physicochemical properties of red ginseng milk (0.5–2%) were measured including pH, titratable acidity, color, general composition, and sensory properties. Antioxidant activities were measured using a DPPH radical scavenging activity assay, β-carotene bleaching assay, and ferric thiocyanate assay. Red ginseng in milk had the following effects: the lactose content, titratable acidity, a value (green–red), b value (blue–yellow), and antioxidant effects were increased, whereas the pH and L values (white–black) were decreased [102]. Oligosaccharide and cyclodextrin were mixed with red ginseng milk to improve the taste, and these two additives resulted in stronger sweetness and weaker bitterness [102].

Ginseng and red ginseng milk are manufactured as functional dairy products and their compositions and physicochemical properties have been analyzed by diverse methods. The presence of ginsenosides in ginseng milk was confirmed by HPLC analysis, and it can be expected that they will provide health benefits. The addition of cyclodextrin, banana, and vanilla should reduce bitterness and increase sweetness in red ginseng milk.

Yogurt fortified with ginseng and red ginseng

Yogurt is produced the fermentation of lactose to lactic acid to lower the pH of milk proteins to near their isoelectric points. Starter bacteria are used, including S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus, L. acidophilus, L. casei, and Bifidobacterium sp. [103, 104]. Yogurt types are classified as set, stirred, drinking sweet, fruit, frozen, and dried [103]. Plain yogurt is made by cup incubation of vat incubation, and yogurt is sold as full-fat, low-fat, and non-fat [105]. Plain/stirred yogurt is manufactured through several steps; milk storage, standardization, pre-heating, homogenization, heat/cooling, inoculation, sugar or flavor preparation, filler, cooling, and cold storage [105].

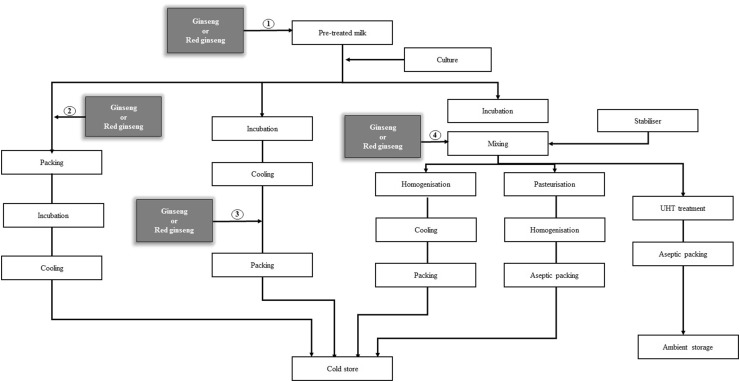

Several research groups have manufactured yogurts fortified with ginseng and red ginseng (Tables 3, 4; Fig. 2). Ginseng yogurt was evaluated for its physicochemical, microbial, and sensory properties and functional effects [106–116]. Mice that administered 2% ginseng yogurt using starter cultures of L. acidophilus L 54, S. thermophilus CHR 16–18, and B. bifidum ATCC 11863 for 3 weeks, showed an increase of HDL cholesterol content, and a decrease of blood glucose level, total cholesterol content, LDL-cholesterol content, and cholesterol ester content [106]. Kim [107, 108] made a yogurt fortified with ginseng extract, white ginseng extract, and tail ginseng extract using S. thermophilus 018812 and L. bulgaricus 011711. Ginseng, white ginseng, and tail ginseng affected the pH, titratable acidity, viscosity, and viable cell counts of the product. Sensory evaluations showed that ginseng and tail ginseng had potential as dairy product components [107, 108]. Lee et al. [109] made yogurts with diverse concentration (0.5–2%) of ginseng that were incubated using L. bulgaricus KCTC 3188 and S. thermophilus KCTC 3658. The addition of ginseng affected the pH value, titratable acidity, lactic acid bacteria counts, viscosity, amino acid content, and organic acids content, because ginseng promoted acid formation by lactic acid bacteria [109]. In addition, yogurt products with different concentrations of ginseng were tested by sensory evaluation [109]. In another study, a yogurt containing 1–3% ginseng was fermented with B. minimum KK-1 and B. cholerium KK-2 [110]. This ginseng yogurt did not score highly in assessment by consumers, however, an increase in the concentration of ginseng enabled an increase of viable bacterial cell counts [110]. Hekmat et al. [114] investigated a yogurt supplemented with ginseng extracts produced by the alcohol and water. The yogurt was inoculated with L. rhamnosus GR-1 and stored for 28 days. The viable cells of L. rhamnosus GR-1 remained in the ginseng-supplemented yogurt during storage and this results indicated that L. rhamnosus GR-1 was stable in ginseng [114]. Cimo et al. [115] made yogurt containing P. quinquefolius (American ginseng roots) and inoculated L. rhamnosus GR-1 as the mother culture and L. bulgaricus, L. delbrueckii, and S. thermophilus as starter culture. This study indicated that American ginseng improved the viability of L. rhamnosus GR-1 and the mother culture enhanced quantity of ginsenosides Rg1, Re, Rb1, and Rb2 in American ginseng [115]. Yogurt was made by inoculating L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus, and B. bifidum and adding nanopowderd and powdered ginseng (concentrations of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7%) [116]. This study showed that nanopowdered and powdered ginseng improved viable bacterial cell number, physicochemical properties, DPPH radical scavenging activity, and sensory evaluation results and changed the color of the yogurts during storage [116]. Especially, the nanopowdered ginseng showed remarkable results than the powdered ginseng on lower concentration [116]. Addition of ginseng affected physicochemical properties and improved functionalities of product.

Table 3.

Microbial strains and conditions for manufacture of yogurt fortified with ginseng

| Type | Starter culturea | Fermentation conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt | L. acidophilus L. 54, S. thermopilus CHR 16–18, B. bifidum ATCC 11863 | Ginseng extract (2%); inoculation volume, 2%; incubation temperature, 37 °C | [106] |

| S. thermophilus 018812, L. bulgaricus 011711 | Ginseng extract (39 mg/g saponin); additives, 8% sugar; inoculation volume, 2%; incubation temperature, 42 °C | [107, 108] | |

| L. bulgaricus KCTC 3188, S. thermophilus KCTC 3658 | Ginseng extract (0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2%); inoculation volume, 2%; incubation temperature, 37 °C | [109] | |

| B. minimum KK-1, B. cholerium KK-2 | Ginseng extract (1, 2, and 3%); additives, 7% sugar; inoculation volume, 3%; incubation temperature, 37 °C | [110] | |

| Bifidobacterium sp. KK-1, KK-2, K-103, K-506, L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus | Ginseng powder (1%); additives, 0.1% vit. C; inoculation volume, 1% (each culture); incubation temperature, 37 °C | [111] | |

| Kefir starter (S. lactis, S. cremoris, S. diacetylactis, L. casei var. rhamnosus, L. acidophilus) | Ginseng (0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2%); incubation temperature, 23 °C | [112] | |

| B. longum H 1 (KCCM 10493) | Ginseng extract concentration; 10 brix | [113] | |

| L. rhamnosus GR-1 | Alcoholic and aqueous ginseng extract (150 or 500 μg/mL milk); inoculation volume, 1%; incubation temperature, 37 °C | [114] | |

| Starter culture (L. bulgaricus, L. delbrueckii, S. thermophilus), Probiotic mother culture (L. rhamnosus GR-1) | Ginseng extract (0.5, 1, and 2%); inoculation volume, 2% starter culture and 4% probiotic mother culture; incubation temperature, 37.5 °C | [115] | |

| Chr. Hansen (L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus, B. bifidum) | Nanopowdered ginseng (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7%); inoculation volume, 0.02%; incubation temperature, 43 °C | [116] |

a L., Lactobacillus; S., Streptococcus; B., Bifidobacterium

Table 4.

Microbial strains and conditions for manufacture of yogurt fortified with red ginseng

| Type | Starter culturea | Fermentation conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt | L. acidophilus KCTC 3150, L. salivarius subsp. salivarius CNU 27 | Red ginseng extract (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 1%); inoculation volume, 2% (each culture); incubation temperature, 37 °C | [117] |

| Yomix 321 (S. thermophilus, L. bulgaricus) | Red ginseng extract (0.25, 0.5, and 1%); additives, 1.5% glucose; incubation temperature, 42 °C | [118] | |

| Yo-MIX 401 (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus) | Red ginseng extract (0.1–0.3%); incubation temperature, 43 °C | [119] | |

| L. acidophilus, S. thermophilus | Red ginseng extract (0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2%); inoculation volume, 0.02%; incubation temperature, 40 °C | [120] |

a L., Lactobacillus; S., Streptococcus

Fig. 2.

Manufacturing process of yogurt fortified with ginseng and red ginseng [106–120, 122]. The addition of ginseng or red ginseng before incubation could improve the pharmaceutical effect because of bioconversion [1, 2]. The addition of ginseng or red ginseng after incubation did not affect the growth of lactic acid bacteria [3, 4]

Red ginseng yogurt was evaluated for its physicochemical, microbial, taste, and functional properties [117–120]. Red ginseng yogurt was made by mixing skim milk, soy milk, and red ginseng (0.1–1.0%) and inoculating L. acidophilus KCTC 3150 and L. salivarius subsp. salivarius CNU 27 as starter cultures [117]. The pH, titratable acidity, viable cell counts, viscosity, carbohydrate content, organic acid content, and sensory properties were examined. Red ginseng promoted the growth of lactic acid bacteria through bioactive components [117]. In addition, red ginseng improved the yield of enzymes that hydrolyze carbohydrates, resulting in a change in lactose content [117]. In another study, a yogurt containing 0.25–1% red ginseng extract was analyzed to determine its physicochemical and antioxidant properties [118]. The red ginseng content of the yogurt was decided according to the effect on its sensory properties, especially, bitterness and astringent taste of red ginseng [118]. Red ginseng yogurt had a higher antioxidant capacity because of the phenols and flavonoids in red ginseng [118]. Choi et al. [119] made a red ginseng yogurt that contained 0.1–0.3% red ginseng, and used L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus as starter cultures. Red ginseng yogurt was assessed by its contents of protein, fat, moisture, salt, and total solids, as well as its pH value, and the concentration of red ginseng was decided according to the results of sensory evaluations [119]. Jung et al. [120] developed a red ginseng yogurt by adding 0.5–2% red ginseng extract and inoculating the culture with L. acidophilus and S. thermophilus. This red ginseng yogurt was assessed for its physicochemical and microbial properties, and antioxidant effects. The addition of red ginseng extract affected the composition, color, incubation time, and antioxidant capacity of the yogurt. Red ginseng promoted the growth of lactic acid bacteria, which reduced the fermentation time, and the fat content of the yogurt was also lower [120]. The potential use of ginseng and red ginseng as additives in dairy products was assessed through physicochemical analysis, sensory test, and functional evaluation. The inclusion of ginseng or red ginseng in yogurt can potentially be adjusted to meet the preferences of consumers while providing functionalities such as antioxidant and anti-tumor effects.

Cheese fortified with ginseng and red ginseng

Cheese is produced in more than 2000 varieties worldwide, which are divided into three major types: rennet or natural, fresh or non-ripened, and processed [96]. Cheese consists of fat, cholesterol, protein, lactose, vitamins, and minerals. Starter cultures for cheese include Lactococcus sp. (Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris and Lc. lactis subsp. lactis), Leuconostoc sp., S. thermophilus, and Lactobacillus sp. (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis, and L. helveticus) [121]. Cheese is made via several steps, including preripening, curding, moulding, pressing, salting, drying, ripening, and packing [122].

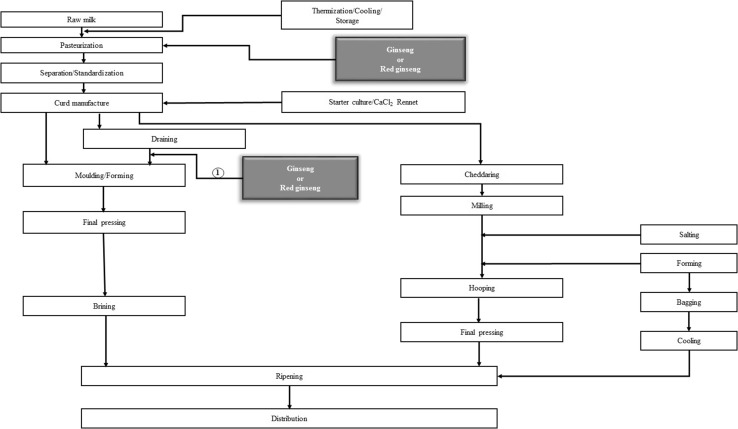

Several research teams have manufactured diverse cheeses fortified with additives including red ginseng (Table 5; Fig. 3). Red ginseng cheese has been evaluated for its physicochemical properties and taste [123–126]. Further, other components such as black garlic and Rubus coreanus have been included in red ginseng cheese [127, 128]. Park et al. [123] made fresh cheese containing fermented red ginseng (1, 3, and 5%) by L. acidophilus. During the storage period, the number of viable cells of lactic acid bacteria in the red ginseng cheese increased, because lactic acid bacteria used red ginseng as a nutrient. The acceptability of the cheese to consumers was decreased in proportion to the concentration of red ginseng because of red ginseng flavor [123]. Nam et al. [124] made red ginseng cheese with the addition of the amino acid-fermented red ginseng condensate to reduce the bitterness added by red ginseng. In other studies, asiago cheese was fortified with red ginseng extracts, red ginseng hydrolyzates, nanopowdered red ginseng, and powdered red ginseng [125, 126]. The red ginseng additives affected the physicochemical properties, numbers of viable cells of lactic acid bacteria, components, and sensory aspects of the asiago cheese during ripening. Previous studies demonstrated that a low concentration of red ginseng extract, red ginseng hydrolysate, nanopowdered red ginseng, and powdered red ginseng was acceptable for utilization in dairy products [125, 126]. Chung et al. [127] made three types of cheese, namely mozzarella, cheddar, and appenzeller, which were fortified with red ginseng and black garlic extract. Chung et al. [128] made appenzeller cheese fortified with fermented red ginseng and Rubus coreanus using L. acidophilus. These fortified cheeses were evaluated as having excellent tastes. In Korea, cheeses fortified with nutrients and flavors have sold, but research has been lacking about the physicochemical and microbial properties, functionality, and appeal of red ginseng cheese. There is a potential for the dairy industry to conduct research with the aim of reducing the flavor and bitterness imparted by red ginseng and improve the taste while adding the functionality.

Table 5.

Microbial strains and conditions for manufacture of cheese fortified with red ginseng

| Type | Starter culturea | Fermentation conditions | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheese | LYO50 (Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis) | Fermented red ginseng (1, 3, and 5%); inoculation volume, 0.003%; incubation temperature, 30–32 °C | [123] |

| ABT-5 (L. acidophilus, Bifidobacterium sp., S. thermophilus) | Inoculation volume, 0.004% | [124] | |

| Flora Danica (Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris) | Red ginseng extract and red ginseng hydrolyzates (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5%); inoculation volume, 1% | [125] | |

| Flora Danica (Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris) | Nanopowdered red ginseng and powdered red ginseng (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5%); inoculation volume, 1% | [126] | |

| Mozzarella: L. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus, Cheddar and appenzeller: ALP-DIP D (CHOOZIT Alp D; Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis, S. salvarius subsp. thermophilus, L. helveticus, L. lactis) | Red ginseng extract (0.001–10%); additives, 0.1–20% black garlic extract; inoculation volume, 1.5% | [127] | |

| FLORA-DANICA (Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris, Lc. lactis subsp. diacetylactis, Lc. lactis subsp. lactis, Leu. mesenteroides subsp. cremoris | Fermented red ginseng and Rubus coreanus (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5%); inoculation volume, 0.003% | [128] |

a L., Lactobacillus; S., Streptococcus; B., Bifidobacterium; Lc., Lactococcus; Leu., Leuconostoc

Fig. 3.

Manufacturing process of cheese fortified with ginseng and red ginseng [122–128]. Cheese was fortified with ginseng or red ginseng fermented product, powder, and solution [1]

In conclusion, ginseng and red ginseng are being developed, prepared, and sold in various forms, such as concentrate, tablet, tea, and powder, to enhance consumer acceptance. The diverse functionalities of ginseng and red ginseng can be attributed to ginsenosides, which are their main pharmacologically active components. To enhance their functionalities, microorganisms and enzymes are being used to convert ginsenosides into smaller minor ginsenoside molecules, although studies on the functionalities of ginsenosides, and the microorganisms and enzymes used for the conversion, are ongoing. Dairy products are known worldwide as highly nutritious foods, with milk, yogurt, and cheese being the most common examples. Recent studies have examined approaches for increasing the nutritional value of dairy products by adding ginseng or red ginseng. These materials have an impact on the physicochemical properties of dairy products. Other studies are being conducted to identify approaches for enhancing the consumer acceptability of dairy products by adding various materials such as cyclodextrin, black garlic, and Korean black raspberry, in addition to ginseng or red ginseng. Although anti-cholesterol and antioxidant effects have been identified as functionalities of dairy products containing ginseng or red ginseng, experiments on other functionalities are still lacking. Moving forward, additional functionality testing on dairy products containing ginseng or red ginseng should be conducted to provide a foundation of basic data required for their use as functional food ingredients.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by High Value added Food Technology Development Program, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (314073-03) and the Priority Research Centers Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0093824).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. 2015 An actual output of functional food. http://www.mfds.go.kr. Accessed Oct. 31, 2016

- 2.Baeg IH, So SH. The world ginseng market and the ginseng (Korea) J. Ginseng Res. 2013;37:1–7. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2013.37.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.In G, Ahn NG, Bae BS, Lee MW, Park HW, Jang KH, Cho BG, Han CK, Park CK, Kwak YS. In situ analysis of chemical components induced by steaming between fresh ginseng, steamed ginseng, and red ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2017;41:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gui Y, Ryu GH. Effects of extrusion cooking on physicochemical properties of white and red ginseng (powder) J. Ginseng Res. 2014;38:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Im K, Kim J, Min H. Ginseng, the natural effectual antiviral: protective effects of Korean red ginseng against viral infection. J. Ginseng Res. 2016;40:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nam KY. The comparative understanding between red ginseng and white ginsengs processed ginsengs (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) J. Ginseng Res. 2005;29:1–18. doi: 10.5142/JGR.2005.29.1.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Ginseng statistics book. 2015. Available from: http://www.mafra.go.kr. Accessed Oct. 28, 2016.

- 8.Ryu GH. Present status of red ginseng products and its manufacturing process. Food Ind. Nutr. 2003;8:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JW. Market trends and prospect of red ginseng products pp. 175. In: 2010 Spring Ginseng Conference. May 7, Olympic Parktel, Seoul, Korea. The Korean Society of Ginseng, Seoul, Korea (2010)

- 10.Lee JW. The industry status of red ginseng products pp. 7. In: 2012 Symposium. May 11–12, Korea National College of Agriculture and Fisheries, Jeonju-si, Jeollabuk-do, Korea. The Plant Resources Society of Korea, Jecheon-si, Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea (2012)

- 11.Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. 2013 Market condition report of Korean dairy products. Available from: http://www.mafra.go.kr. Accessed Jan. 11, 2016

- 12.The association for packaging and processing technologies. Executive summary and industry perspective. Available from: http://www.pmmi.org. Accessed Oct. 21, 2016

- 13.Kennedy DO, Scholey AB. Ginseng: potential for the enhancement of cognitive performance and mood. Pharmacol. Biochem. Be. 2003;75:687–700. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jee HS, Chang KH, Park SH, Kim KT, Paik HD. Morphological characterization, chemical components, and biofunctional activities of Panax ginseng, Panax quinquefolium, and Panax notoginseng roots: a comparative study. Food Rev. Int. 2014;30:91–111. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2014.883631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang S, Wang R, Zeng W, Zhu W, Zhang X, Wu C, Song J, Zheng Y, Chen P. Resource investigation of traditional medicinal plant Panax japonicus (T.Nees) C.A. Mey and its varieties in China. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015;166:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeo CR, Yong JJ, Popovich DG. Isolation and characterization of bioactive polyacetylenes Panax ginseng Meyer roots. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2017;139:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi KT, Yang DC. Pharmacological effects and medicinal components of Korean ginseng (Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer) Korean Ginseng Res. Ind. 2012;6:2–21. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim DW, Lee YJ, Min JW, Kim YJ, Rho YD, Yang DC. Conversion of acidic polysaccharide and phenolic compound of changed ginseng by 9 repetitive steaming and drying process, and its effects of antioxidation. Korean J. Orient Physiol. Pathol. 2009;23:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srivastava R, Kulshreshtha DK. Bioactive polysaccharides from plants. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:2877–2883. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(89)80245-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwak YS, Kim YS, Shin HJ, Song YB, Park JD. Anticancer activities by combined treatment of red ginseng acidic polysaccharide (RGAP) and anticancer agents. J. Ginseng Res. 2003;27:47–51. doi: 10.5142/JGR.2003.27.2.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SM, Bae BS, Park HW, Ahn NG, Cho BG, Cho YL, Kwak YS. Characterization of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng Meyer): history, preparation method, and chemical composition. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh MH, Park YS, Lee H, Kim NY, Jang YB, Park JH, Kwak JY, Park YS, Park JD, Pyo MK. Comparison of physicochemical properties and malonyl ginsenoside contents between white and red ginseng. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 2016;47:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim E, Jin Y, Kim KT, Lim TG, Jang M, Cho CW, Rhee YK, Hong HD. Effect of high temperature and high pressure on physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of Korean red ginseng. Korean J. Food Nutr. 2016;29:438–447. doi: 10.9799/ksfan.2016.29.3.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, Virgous C, Si H. Ginseng and obesity: observations and understanding in cultured cells, animals and humans. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016;44:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hossen MJ, Hong YD, Baek KS, Yoo S, Hong YH, Kim JH, Lee JO, Kim D, Park J, Cho JY. In vitro antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of the compound K-rich fraction BIOGF1 K, prepared from Panax ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2017;41:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng L, Liu XM, Cao FR, Wang LS, Chen YX, Pan RL, Liao YH, Wang Q, Chang Q. Anti-stress effects of ginseng total saponins on hindlimb-unloaded rats assessed by a metabolomics study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;188:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma J, Goyal PK. Chemoprevention of chemical-induced skin cancer by Panax ginseng root extract. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park D, Bae DK, Jeon JH, Lee J, Oh N, Yang G, Yang YH, Kim TK, Song J, Lee SH, Song BS, Jeon TH, Kang SJ, Joo SS, Kim SU, Kim YB. Immunopotentiation and antitumor effects of a ginsenoside Rg3-fortified red ginseng preparation in mice bearing H460 lung cancer cells. Environ. Toxicol. Phar. 2011;31:397–405. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KH, Bae IY, Park SI, Park JD, Lee HG. Antihypertensive effect of Korean red ginseng by enrichment of ginsenoside Rg3 and arginine-fructose. J. Ginseng Res. 2016;40:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SJ, Lee MJ, Ko YJ, Choi HR, Jeong JT, Choi KM, Cha JD, Hwang SM, Jung HK, Park JH, Lee TB. Effects of extracts of unripe black raspberry and red ginseng on cholesterol synthesis. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013;45:628–635. doi: 10.9721/KJFST.2013.45.5.628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jun YL, Bae CH, Kim D, Koo S, Kim S. Korean red ginseng protects dopaminergic neurons by suppressing the cleavage of p35–p25 in a Parkinson’s disease mouse model. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:148–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen CT, Luong TT, Kim GL, Pyo S, Rhee DK. Korean red ginseng inhibits apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells via estrogen receptor β-mediated phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/Akt signaling. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y, Oh S. Administration of red ginseng ameliorates memory decline in aged mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee H, Choi J, Shin SS, Yoon M. Effects of Korean red ginseng (Panax ginseng) on obesity and adipose inflammation in ovariectomized mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;178:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuzzati N. Analysis methods of ginsenosides. J. Chromatogr. B. 2004;812:119–133. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(04)00645-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mroczek T. Qualitative and quantitative two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography/high performance liquid chromatography/diode-array/electrospray-ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry of cholinesterase inhibitors. J. Pharmaceut. Biomed. 2016;129:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He C, Feng R, Sun Y, Chu S, Chen J, Ma C, Fu J, Zhao Z, Huang M, Shou J, Li X, Wang Y, Hu J, Wang Y, Zhang J. Simultaneous quantification of ginsenoside Rg1 and its metabolites by HPLC-MS/MS: Rg1 excretion in rat bile, urine and feces. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2016;6:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin BK, Kwon SW, Park JH. Chemical diversity of ginseng saponins from Panax ginseng. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim YJ, Zhang D, Yang DC. Biosynthesis and biotechnological production of ginsenosides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33:717–735. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui L, Wu SQ, Zhao CA, Yin CR. Microbial conversion of major ginsenosides in ginseng total saponins by Platycodon grandiflorum endophytes. J. Ginseng Res. 2016;40:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim WY, Kim JM, Han SB, Lee SK, Kim ND, Park MK, Kim CK, Park JH. Steaming of ginseng at high temperature enhances biological activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2000;63:1702–1704. doi: 10.1021/np990152b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang XD, Yang YY, Ouyang DS, Yang GP. A review of biotransformation and pharmacology of ginsenoside compound K. Fitoterapia. 2015;100:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noh KH, Son JW, Kim HJ, Oh DK. Ginsenosid compound K production from ginseng root extract by a thermostable β-glycosidase form Sulfolobus solfataricus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009;73:316–321. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chang KH, Jee HS, Lee NK, Park SH, Lee NW, Paik HD. Optimization of the enzymatic production of 20(S)-ginsenoside Rg3 from white ginseng extract using response surface methodology. New Biotechnol. 2009;26:181–186. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Choi KD, Yu H, Jin F, Im WT. Production of ginsenoside F1 using commercial enzyme cellulase KN. J. Ginseng Res. 2016;40:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chi H, Lee BH, You HJ, Park MS, Ji GE. Differential transformation of ginsenosides from Panax ginseng by lactic acid bacteria. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2006;16:1629–1633. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bai Y, Gänzle MG. Conversion of ginsenosides by Lactobacillus plantarum studied by liquid chromatography coupled to quadrupole trap mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2015;76:709–718. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park SE, Na CS, Yoo SA, Seo SH, Son HS. Biotransformation of major ginsenosides in ginsenoside model culture by lactic acid bacteria. J. Ginseng Res. 2017;41:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quan LH, Piao JY, Min JW, Kim HB, Kim SR, Yang DU, Yang DC. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to prosapogenins, gypenoside XVII, ginsenoside Rd, ginsenoside F2, and compound K by Leuconostoc mesenteroides DC102. J. Ginseng Res. 2011;35:344–351. doi: 10.5142/jgr.2011.35.3.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ku S, You HJ, Park MS, Ji GE. Whole-cell biocatalysis for producing ginsenoside Rd from Rb1 using Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2016;26:1206–1215. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1601.01002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li L, Shin SY, Lee SJ, Moon JS, Im WT, Han NS. Production of ginsenoside F2 by using Lactococcus lactis with enhanced expression of β-glucosidase gene from Paenibacillus mucilaginosus. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2016;64:2506–2512. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu H, Liu Q, Zhang C, Lu M, Fu Y, Im WT, Lee ST, Jin F. A new ginsenosidase from Aspergillus strain hydrolyzing 20-O-multi-glycoside of PPD ginsenoside. Process Biochem. 2009;44:772–775. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jo MN, Jung JE, Yoon HJ, Chang KH, Jee HS, Kim KT, Paik HD. Bioconversion of ginsenoside Rb1 to the pharmaceutical ginsenoside compound K using Aspergillus usamii KCTC 6954. Korean J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;42:347–353. doi: 10.4014/kjmb.1407.07010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chang KH, Jo MN, Kim KT, Paik HD. Purification and characterization of a ginsenoside Rb1-hydrolyzing β-glucosidase from Aspergillus niger KCCM 11239. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13:12140–12152. doi: 10.3390/ijms130912140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang KH, Jo MN, Kim KT, Paik HD. Evaluation of glucosidases of Aspergillus niger strain comparing with other glucosidases in transformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to ginsenosides Rg3. J. Ginseng Res. 2014;38:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu CY, Zhou RX, Sun CK, Jin YH, Yu HS, Zhang TY, Xu LQ, Jin FX. Preparation of minor ginsenosides C-Mc, C-Y, F2, and C-K from American ginseng PPD-ginsenoside using special ginsenosidase type-I from Aspergillus niger g.848. J. Ginseng Res. 39: 221–229 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Kim BH, Kang JH, Lee SY, Cho HJ, Kim YJ, Kim YJ, Ahn SC. Biotransformation of ginseng to compound K by Aspergillus oryzae. J. Life Sci. 2006;16:136–140. doi: 10.5352/JLS.2006.16.1.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan Q, Zhou XW, Zhou W, Li XW, Feng MQ, Zhou P. Purification and properties of a novel β-glucosidase, hydrolyzing ginsenoside Rb1 to CK, from Paecilomyces bainier. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;18:1081–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yan Q, Zhou W, Shi XL, Zhou P, Ju DW, Feng MQ. Biotransformation pathways of ginsenoside Rb1 to compound K by β-glucosidases in fungus Paecilomyces bainier sp. 229. Process Biochem. 2010;45:1550–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ye L, Zhou CQ, Zhou W, Zhou P, Chen DF, Liu XH, Shi XL, Feng MQ. Biotransformation of ginsenoside Rb1 to ginsenoside Rd by highly substrate-tolerant Paecilomyces bainier 229-7. Bioresource Technol. 2010;101:7872–7876. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ahmed T, Raza SH, Maryam A, Setzer WN, Braidy N, Nabavi SF, Oliverira MR, Nabavi SM. Ginsenoside Rb1 as a neuroprotective agent: a review. Brain Res. Bull. 2016;125:30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang Q, Gao B, Jie Q, Wei BY, Fan J, Zhang HY, Zhang JK, Li XJ, Shi J, Luo ZJ, Yang L, Liu J. Ginsenoside-Rb2 displays anti-osteoporosis effects through reducing oxidative damage and bone-resorbing cytokines during osteogenesis. Bone. 2014;66:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang T, Yu X, Qu S, Xu H, Han B, Sui D. Effect of ginsenoside Rb3 on myocardial injury and heart function impairment induced by isoproterenol in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;636:121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu T, Yang Y, Kwak YS, Song GG, Kim MY, Rhee MH, Cho JY. Ginsenoside Rc from Panax ginseng exerts anti-inflammatory activity by targeting TANK-binding kinase 1/interferon regulatory factor-3 and p38/ATF-2. J. Ginseng Res. 2017;41:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ye R, Li N, Han J, Kong X, Cao R, Rao Z, Zhao G. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rd against oxygen-glucose deprivation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. Res. 2009;64:306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang YX, Wang L, Xiao EL, Li SJ, Chen JJ, Gao B, Min GN, Wang ZP, Wu YJ. Ginsenoside-Rd exhibits anti-inflammatory activities through elevation of antioxidant enzyme activities and inhibition of JNK and ERK activation in vivo. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013;17:1094–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Junmin S, Hongxiang L, Zhen L, Chao Y, Chaojie W. Ginsenoside Rg3 inhibits colon cancer cell migration by suppressing nuclear factor kappa B activity. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015;35:440–444. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6272(15)30122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee SJ, Lee WJ, Chang SE, Lee GY. Antimelanogenic effect of ginsenoside Rg3 through extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated inhibition of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Y, Liu QZ, Xing SP, Zhang JL. Inhibiting effect of Endostar combined with ginsenoside Rg3 on breast cancer tumor growth in tumor-bearing mice. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2016;9:180–183. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hwang JT, Kim SH, Lee MS, Kim SH, Yang HJ, Kim MJ, Kim HS, Ha J, Kim MS, Kwon DY. Anti-obesity effects of ginsenoside Rh2 are associated with the activation of AMPK signaling pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocyte. Biochem Bioph. Res. Co. 2007;364:1002–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yi PF, Bi WY, Shen HQ, Wei Q, Zhang LY, Dong HB, Bai HL, Zhang C, Song Z, Qin QQ, Lv S, Wu SC, Fu BD, Wei XB. Inhibitory effects of sulfated 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 on the release of pro-inflammatory mediators in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;712:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Han S, Jeong AJ, Yang H, Kang KB, Lee H, Yi EH, Kim BH, Cho CH, Chung JW, Sung SH, Ye SK. Ginsenoside 20(S)-Rh2 exerts anti-cancer activity through targeting IL-6-induced JAK2/STAT3 pathway in human colorectal cancer cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kang S, Im K, Kim G, Min H. Antiviral activity of 20(R)-ginsenoside Rh2 against murine gammaherpesvirus. J. Ginseng Res. in press (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Mai TT, Moon JY, Song YW, Viet PQ, Phuc PV, Lee JM, Yi TH, Cho M, Cho SK. Ginsenoside F2 induces apoptosis accompanied by protective autophagy in breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;321:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siraj FM, SathishKumar N, Kim YJ, Kim SY, Yang DC. Ginsenoside F2 possesses anti-obesity activity via binding with PPARγ and inhibiting adipocyte differentiation in the 3T3-L1 cell line. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Ch. 2015;30:9–14. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2013.871006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park SH, Seo W, Eun HS, Kim SY, Jo E, Kim MH, Choi WM, Lee JH, Shim YR, Cui CH, Kim SC, Hwang CY, Jeong WI. Protective effects of ginsenoside F2 on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced skin inflammation in mice. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co. 2016;478:1713–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peng L, Sun S, Xie LH, Wicks SM, Xie JT. Ginsenoside Re: pharmacological effects on cardiovascular system. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2012;30:e183–e188. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2011.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gao Y, Yang MF, Su YP, Jiang HM, You XJ, Yang YJ, Zhang HL. Ginsenoside Re reduces insulin resistance through activation of PPAR-γ pathway and inhibition of TNF-α production. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;147:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nemmani KVS, Ramarao P. Ginsenoside Rf potentiates U-50, 488H-induced analgesia and inhibits tolerance to its analgesia in mice. Life Sci. 2003;72:759–768. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(02)02333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu Z, Qi Y, Cheng Z, Zhu X, Fan C, Yu SY. The effects of ginsenoside Rg1 on chronic stress induced depression-like behaviors, BDNF expression and the phosphorylation of PKA and CREB in rats. Neuroscience. 2016;322:358–369. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xin Y, Wei J, Chunhua M, Danhong Y, Jianguo Z, Zongqi C, Jian-an B. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury in mice through suppression of inflammation. Phytomedicine. 2016;23:583–588. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhou T, Zu G, Zhang X, Wang X, Li S, Gong X, Liang Z, Zhao J. Neuroprotective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in both in vivo and in vitro models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:480–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Li Y, Wang F, Luo Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 protects against sepsis-associated encephalopathy through beclin 1-independent autophagy in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2017;207:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li N, Liu B, Dluzen DE, Jin Y. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg2 against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;111:458–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang G, Liu A, Zhou Y, San X, Jin T, Jin Y. Panax ginseng ginsenoside-Rg2 protects memory impairment via anti-apoptosis in a rat model with vascular dementia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115:441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kang HJ, Huang YH, Lim HW, Shin D, Jang K, Lee Y, Kim K, Lim CJ. Stereospecificity of ginsenoside Rg2 epimers in the protective response against UV-B radiation-induced oxidative stress in human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Photoch. Photobio. B. 2016;165:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zheng H, Jeong Y, Song J, Ji GE. Oral administration of ginsenoside Rh1 inhibits the development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions induced by oxazolone in hairless mice. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoon JH, Choi YJ, Lee SG. Ginsenoside Rh1 suppresses matrix metalloproteinase-1 expression through inhibition of activator protein-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012;679:24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee EH, Cho SY, Kim SJ, Shin ES, Chang HK, Kim DH, Yeom MH, Woe KS, Lee J, Sim YC, Lee TR. Ginsenoside F1 protects human HaCaT keratinocytes from ultraviolet-B-induced apoptosis by maintaining constant levels of Bcl-2. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:607–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu CF, Liu YL, Song M, Liu W, Wang JH, Li X, Yang JY. Protective effects of pseudoginsenoside-F11 on methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem Be. 2003;76:103–109. doi: 10.1016/S0091-3057(03)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang CM, Liu MY, Wang F, Wei MJ, Wang S, Wu CF, Yang JY. Anti-amnesic effect of pseudoginsenoside-F11 in two mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacol. Biochem Be. 2013;106:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang X, Wang C, Wang J, Zhao S, Zhang K, Wang J, Zhang W, Wu C, Yang J. Pseudoginsenoside-F11 (PF11) exerts anti-neuroinflammatory effects on LPS-activated microglial cells by inhibiting TLR4-mediated TAK1/IKK/NF-κB. MAPKs and Akt signaling pathways. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:642–656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim S, Oh MH, Kim BS, Kim WI, Cho HS, Park BY, Park C, Shin GW, Kwon J. Upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 by ginsenoside Ro attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in macrophage cells. J. Ginseng Res. 2015;39:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jgr.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiao-Hong Z, Xian-Xiang XU, Tao XU. Ginsenoside Ro suppresses interleukin-1β-induced apoptosis and inflammation in rat chondrocytes by inhibiting NF-κB. Chin. J. Nat. Medicines. 2015;13:283–289. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(15)30015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walstra P, Wouters JTM, Geurts TJ. Dairy science and technology. 2th ed. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp. 3–16 (2006)

- 96.Spreer E. Milk and dairy product technology. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1998. pp. 3–337. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lee SS, Park JM, Oh HI, Kwak HS. Optimization of saponin extraction conditions in ginseng milk using response surface methodology. J. Ginseng Res. 1994;18:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tárrega A, Salvador A, Meyer M, Feuillère N, Ibarra A, Roller M, Terroba D, Madera C, Iglesias JR, Echevarría J, Fiszman S. Active compounds and distinctive sensory features provided by American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius L.) extract in a new functional milk beverage. J. Dairy Sci. 2012;95:4246–4255. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bea JS, Lee HJ, Lee US, Hong ST. Development of red ginseng milk containing lactoferrin (abstract no. P3-61). In: Abstracts: 2010 International symposium and annual meeting. October 27–29, Hotel Inter-Burgo, Daegu, Korea. The Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition, Seoul, Korea (2010)

- 100.Park R, Choi KM, Ryu MS, Park BH, Jeong MR, Yoo BW. Functional milk comprising Panax ginseng concentrate and cyclodextrin. Korea Patent 10-1313640 (2013)

- 101.Chung BH, Huh J. Red ginseng milk beverage containing black garlic and method for preparing thereof. Korea Patent 10-1701809 (2017)

- 102.Jung JE, Yoon HJ, Yu HS, Lee NK, Jee HS, Paik HD. Physicochemical and antioxidant properties of milk supplemented with red ginseng extract. J. Dairy Sci. 2015;98:95–99. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-8476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yildiz F. Development and manufacture of yogurt and other functional dairy products. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL, USA. pp. 1–45 (2010)

- 104.Muehlhoff E, Bennett A, McMahon D. Milk and dairy products in human nutrition. Rome, Italy: Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations; 2013. pp. 41–102. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chandan RC, Kilara A. Manufacturing yogurt and fermented milks. 2th ed. Wiley-Blackwell, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichestesr, West Sussex, UK. pp. 195–295 (2013)

- 106.Goh JS, Chae YS, Gang CG, Kwon IK, Choi M, Lee SK, Kim GY, Ahn JK. Studies on development of ginseng-yogurt and it’s health effect. II. Effect of ginseng-yogurt on the blood glucose, serum cholesterol and inhibition of cancer in mouse. Korean. J. Dairy Sci. 1994;16:253–261. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kim JW. Studies on the characteristics of liquid yoghurt from milk added with ginseng. J. Agr. Sci. 1996;23:219–226. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim JW. Utilization of ginseng products in the manufacture of curd yoghurt. J. Agr. Sci. 1999;26:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee IS, Paek KY. Preparation and quality characteristics of yogurt added with cultured ginseng. Korean J. Food Sci. Technol. 2003;35:235–241. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kim NY, Han MJ. Development of ginseng yogurt fermented by Bifidobacterium spp. Korean J. Food Cook. Sci. 2005;21:575–584. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kim DH, Han MJ, Choo MK. Ginseng fermented by lactic acid bacterium, yoghurt containing the same, and lactic acid bacteria used in the preparation thereof. Korea Patent 10-0497895 (2005)

- 112.Jeong YH, Kang IJ. Method for producing functional fermented milk using vinegar hydrolysis ginseng. Korea Patent 10-2009-0056182 (2009)

- 113.Kim KT, Lee YC, Noh JH, Kim YC, Choi SY, Lee YK Cho CW, Lee MH, Kim SW, Chon YI, Hong JC, Song GR, Seong WJ, Jung YJ, Cho MH. Fermented ginseng yoghurt drink composition and preparation method thereof. Korea Patent 10-1158506 (2012)

- 114.Hekmat S, Cimo A, Soltani M, Lui E, Reid G. Microbial properties of probiotic fermented milk supplemented with ginseng extracts. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013;4:392–397. doi: 10.4236/fns.2013.44050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cimo A, Soltani M, Lui E, Hekmat S. Fortification of probiotic yogurt with ginseng (Panax quinquefolius) extract. J. Food Nutr. Disor. 2013;2:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee SB, Ganesan P, Kwak HS. Comparison of nanopowdered and powdered ginseng-added yogurt on its physicochemical and sensory properties during storage. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2013;33:24–30. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2013.33.1.24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Bae HC, Nam MS. Properties of the mixed fermentation milk added with red ginseng extracts. Korean J. Food Sci. An. 2006;26:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kim SI, Ko SH, Lee YJ, Choi HY, Han YS. Antioxidant activity of yogurt supplemented with red ginseng extract. Korean J. Food Cook. Sci. 2008;24:358–366. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Choi KM, Yoo BW, Kim JH, Kim GI, Jang SM, Jeong HK, Choi HY, Kim KH, Kim MJ. Red ginseng yoghurt comprising red ginseng concentrate. Korea Patent 10-1357686 (2014)

- 120.Jung J, Paik HD, Yoon HJ, Jang HJ, Jeewanthi RKC, Jee HS, Li X, Lee NK, Lee SK. Physicochemical characteristics and antioxidant capacity in yogurt fortified with red ginseng extract. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. 2016;36:412–420. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2016.36.3.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fox PF, Guinee TP, Cogan TM, McSweeney PLH. Fundamentals of cheese science. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: An Aspen Publication, Aspen Publishers Inc; 2000. pp. 1–544. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stromblad J. Dairy processing handbook. Yongsan-gu, Seoul, Korea: Tetra Pak Korea; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Park JH, Moon HJ, Oh JH, Lee JH, Jung HK, Choi KM, Cha JD, Lim JY, Han SB, Lee TB, Lee MJ, Choi HR. Changes in the functional components of Lactobacillus acidophilus-fermented red ginseng extract and its application to fresh cheese production. Korean J. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2014;32:47–53. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nam HS, Kim IH, Moon SE, Jo SJ, Lee HY. Cheese manufacturing methods, including ginseng, and it contained. Korea Patent 10-1608146 (2016)

- 125.Choi KH, Min JY, Ganesan P, Bae IH, Kwak HS. Physicochemical and sensory properties of red ginseng extracts or red ginseng hydrolyzates-added asiago cheese during ripening. Asian Aust. J. Anim. 2015;28:120–126. doi: 10.5713/ajas.14.0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Choi KH, Yoo SH, Kwak HS. Comparison of the physicochemical and sensory properties of asiago cheeses with added nano-powdered red ginseng and powdered red ginseng during ripening. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2014;67:348–357. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chung BH, Huh J. Method for preparing red ginseng cheese containing black garlic. Korea Patent 10-1701811 (2017)

- 128.Chung HK, Park JH, Huh CK, Choi HY, Oh JH, Lee JH, Moon HJ, Choi YJ, Yang HS, Kim KH, Choi KM, Cha JD, Hwang SM, Kang JL, Lee TB, Lee MJ, Lee SJ. Manufacturing method for cheese using red ginseng and Rubus coreanus. Korea Patent 10-1631264 (2016)