Abstract

Sandfish (Arctoscopus japonicus) meat and roe were used as natural materials for the preparation of antioxidant peptides using enzymatic hydrolysis. Meat and roe were hydrolyzed using Alcalase 2.4 L and Collupulin MG, respectively. Optimal hydrolysis conditions were determined through the effects of pH, temperature, enzyme concentration, and hydrolysis time on the radical scavenging activity of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). The optimal hydrolysis conditions for meat hydrolysate (MHA) obtained via Alcalase 2.4 L treatment were a pH of 6.0, temperature of 70 °C, enzyme concentration of 5% (w/w), and a hydrolysis time of 3 h. The optimal hydrolysis conditions for roe hydrolysate (RHC) obtained via Collupulin MG treatment were pH 9.0, 60 °C temperature, 5% (w/w) enzyme concentration, and 1 h hydrolysis time. Under the optimal conditions, the DPPH radical scavenging activities of MHA and RHC were 60.04 and 79.65%, respectively. These results provide fundamental data for the production of antioxidant peptides derived from sandfish hydrolysates.

Keywords: Sandfish, Arctoscopus japonicus, Enzymatic hydrolysis, Hydrolysis conditions, Antioxidant peptide

Introduction

Oxidative stress is closely linked to aging and plays an important role in the development and progression of diseases such as Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular disease, neurodegenerative disease, and cancer [1]. Some studies have shown that the hyperproduction of free radicals is a crucial factor in elevating oxidative stress [2]. In addition, oxidative-stress-induced lipid oxidation can cause flavor and texture alterations in food as well as nutrient loss, leading to a reduced shelf-life [3]. Accordingly, many artificial antioxidants such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), and propyl gallate (PG) are widely used as food additives to preserve food quality. However, artificial antioxidants can induce toxic side effects when ingested. Compared with artificial antioxidants, food-borne natural antioxidants such as antioxidant peptides not only have strong antioxidant activities but are also safer for consumption, with no allergenic or carcinogenic properties. Natural antioxidant peptides have been obtained using various methods, including extraction, synthesis, and enzymatic hydrolysis from products with abundant protein content. Of these, antioxidant peptides obtained via enzymatic hydrolysis have been demonstrated frequently in recent studies [4–7]. These antioxidant peptides efficiently inhibit free radicals and contribute toward reducing oxidative stress.

Sandfish, Arctoscopus (A.) japonicus, belongs to the order Perciformes and is a cold-water species. It is widely distributed along the east coast of Korea, north central Japan, Sakhalin, and Alaska and usually lives 100–200 m below the ocean surface, partially buried in sand or mud [8, 9]. Sandfish is a much sought after ingredient in Korean food and is usually eaten whole. The demands for roe are increasing yearly, primarily owing to its unique texture, taste, and health benefits. In addition, A. japonicus is rich in protein and has been identified as a source of bioactive peptides in a preliminary study [5]. Nevertheless, further study on the hydrolytic conditions for antioxidant peptides derived from A. japonicus is needed. Therefore, in this study, meat and roe of A. japonicas were used as natural materials for the preparation of antioxidant peptides using enzymatic hydrolysis. Optimal hydrolysis conditions were established using the radical scavenging activities of both hydrolysates. Based on the results of this study, we aim to provide fundamental data for the production of antioxidant peptides derived from sandfish protein hydrolysates.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sandfish (A. japonicus, 95.0 ± 5.0 g in weight and 20.0 ± 2.2 cm in length) was procured from a wholesale market located in Daegu, Republic of Korea. It was transported with ice to the Department of Food and Nutrition (Yeungnam University) and separated into meat and roe, which were ground using a mixer (M-1211; Starion, Busan, South Korea) and stored under ultrarapid freezing (MDF-435; Sanyo, Tokyo, Japan). Isopropyl alcohol (IPA), 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), dimethyl casein, and tyrosine were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Five hydrolytic enzymes (Alcalase 2.4 L, Collupulin MG, Flavourzyme 500 MG, Neutrase 0.8 L, and Protamex) were purchased from Novo Nordisk Co. (Bagsvaerd, Denmark). The specifications, protease activities, and optimum pH and temperature values of these enzymes are presented in Table 1. The protease activity of each hydrolytic enzyme was measured using casein as a substrate according to the method of Senphan and Benjakul [10]. One unit of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 µmol of tyrosine from 0.1% casein substrate solution per min under optimum conditions.

Table 1.

Specification, optimum pH, and temperature for the activities of various enzymes

| Commercial enzyme | Optimum conditions | Protease activitya (unit/g) | Enzyme composition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Temperature (°C) | |||

| Alcalase 2.4 L | 6.5–8.5 | 55–70 | 2.4 | Endopeptidase |

| Collupulin MG | 5.0–7.5 | 50–70 | 4.6 | Endopeptidase |

| Flavourzyme 500 MG | 5.0–7.0 | 40–60 | 5.0 | Aminopeptidase, exopeptidase |

| Neutrase 0.8 L | 7.0–8.0 | 40–60 | 0.8 | Endopeptidase |

| Protamex | 5.0–7.0 | 50–60 | 1.5 | Endopeptidase |

aOne unit of proteolytic activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that liberates 1 μmol of tyrosine from 0.1% casein substrate solution per min under the optimum conditions

Protein hydrolysis

Before hydrolysis, the meat and roe were defatted to promote extraction through the breakage of chemical bonds in the lipid–protein complexes. Briefly, the ground meat and roe were separately mixed with IPA (1:4, w/v) for 50 min at ambient temperature. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 700×g for 30 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was accumulated and lyophilized. Defatted meat (DM) and defatted roe (DR) were stored at −40 °C.

All hydrolyses were performed in a shaking incubator (KMC-8480SF, Vision Scientific Co., Daejeon, Korea) to control the temperature and in a triangle flask (500 mL) to control the pH throughout the hydrolysis. Samples were hydrolyzed according to the method of Souissi et al. [11]. DM and DR were mixed separately with distilled water at a ratio of 1:10 (w/v) and then boiled at 90 °C for 20 min to deactivate endogenous enzymes. The pH and temperature of each mixture were adjusted to within the optimum pH and temperature range for each enzyme (Table 1). Briefly, pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 1 N HCl or 1 N NaOH, and each enzyme (Alcalase 2.4 L, Collupulin MG, Flavourzyme 500 MG, Neutrase 0.8 L, and Protamex) was added to the reaction mixture to give an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:50 (w/w). The mixture was agitated at 140 rpm in a shaking incubator at 55 °C for 1 h and boiled at 90 °C for 20 min to deactivate enzyme. The DM or DR hydrolysate was centrifuged at 1600×g for 30 min to separate the hydrolysate from the unhydrolyzed fraction. The hydrolyzed supernatant was collected and lyophilized in a freeze dryer (FD-1, Eyela, Tokyo, Japan) and stored at −40 °C for future analysis.

Measurement of antioxidant activity

The 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity method is one of the most convenient and widely used methods for evaluating antioxidant activity. It is very rapid and simple compared with other methods for measuring hydroxyl, superoxide, and 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical scavenging activities [12, 13]. In addition, screening of peptides using the DPPH method has been demonstrated to be effective in identifying those that may possess antioxidant activity [4, 6, 7].

The antioxidant activity of enzymatic hydrolysates was measured using the DPPH radical scavenging activity method described by Jang et al. [5]. Briefly, 1 mL of the sample was mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.2 mM DPPH radical solution. The mixture was then spun using a vortex (Vortex-Genie2, Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY, USA) for 5 s and reacted at 37 °C for 30 min. Absorbance was then measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer (U-2900; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The scavenging activity was calculated as follows: [1 − (A sample/A control)] × 100, where A control is the absorbance of the control (without sample) at 517 nm and A sample is the absorbance of the hydrolysate at 517 nm.

Determination of optimal hydrolysis conditions

pH and temperature

The samples were hydrolyzed separately at different pH values (5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, and 9.0) and temperatures (30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 °C) for 1 h. Enzyme was added to the reaction to give an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:50 (w/w). The reactant was centrifuged at 1600×g for 30 min, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the hydrolyzed supernatant was measured.

Enzyme concentration

The optimal enzyme concentration was determined at the optimal pH and temperature, which were determined prior to the test. The samples were hydrolyzed with different enzyme amounts (Alcalase: 0.12, 0.24, 0.36, 0.48, and 0.60 unit; Collupulin MG: 0.23, 0.46, 0.69, 0.92, and 1.15 unit) corresponding to 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5% of enzyme concentration for 1 h. The mixture was centrifuged at 1600×g for 30 min, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the hydrolyzed supernatant was measured.

Hydrolysis time

The optimal hydrolysis time was measured at the optimal pH and temperature and with the optimal enzyme concentration. Samples were hydrolyzed at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 h time points. Each mixture was centrifuged at 1600×g for 30 min, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity of the hydrolyzed supernatant was measured.

Statistical analysis

All results of the present study are given as the mean and standard deviation (mean ± SD) of three or more iterations. The collected sample data were assayed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and Duncan’s multiple range test was used to identify significant differences (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results and discussion

Effect of enzymes

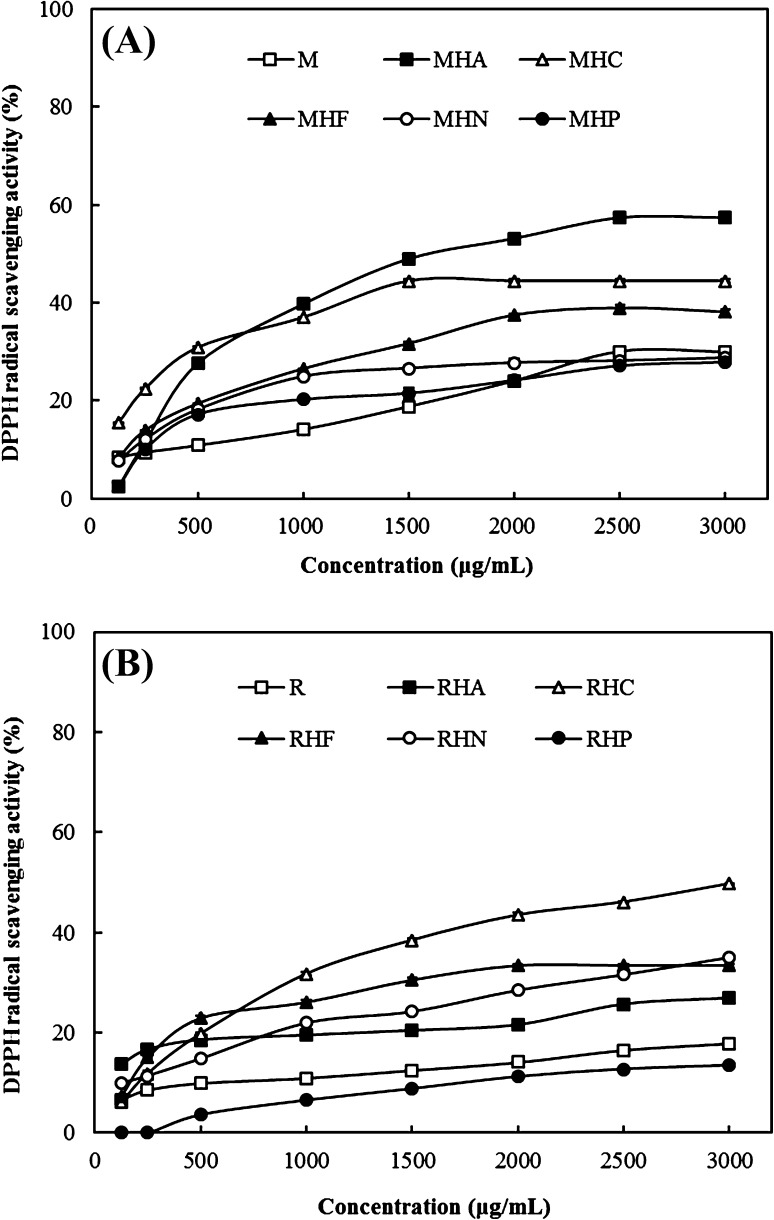

To determine the best enzyme for antioxidant peptide production, the samples were hydrolyzed using five different enzymes (Alcalase 2.4 L, Collupulin MG, Flavourzyme 500 MG, Neutrase 0.8 L, and Protamex). The DPPH radical scavenging activities of the five hydrolysates were evaluated, and the results are shown in Fig. 1. Meat hydrolysate (MH) showed a higher DPPH radical scavenging activity compared with unhydrolyzed meat (M) at concentrations of 500, 1000, 1500, and 2000 μg/mL. However, the DPPH radical scavenging activity of MH obtained using Neutrase 0.8 L (MHN) and Protamex (MHP) was slightly lower than that of M at a concentration of 2500 and 3000 μg/mL. Although the DPPH radical scavenging activity of MH obtained using Collupulin MG (MHC) stopped increasing above a concentration of 1500 μg/mL, most MH was capable of scavenging DPPH radicals in a dose-dependent manner. In particular, the DPPH radical scavenging activity of MH obtained using Alcalase 2.4 L (MHA) was the highest among the hydrolysates, i.e., 39.76, 48.97, 53.14, 57.40, and 57.40% at concentrations of 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500, and 3000 μg/mL, respectively. All roe hydrolysates (RH) except the RH obtained using Protamex (RHP) showed higher DPPH radical scavenging activities compared with unhydrolyzed roe (R). The DPPH radical scavenging activity of the RH obtained using Collupulin MG (RHC) was the highest among the samples. Therefore, the MH and RH of A. japonicus were prepared using Alcalase 2.4 L and Collupulin MG, respectively, for antioxidant peptide production.

Fig. 1.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of various enzymatic hydrolysates obtained from (A) meat and (B) roe of A. japonicus. M unhydrolyzed meat; MHA meat hydrolysate obtained using Alcalase 2.4 L, MHC meat hydrolysate obtained using Collupulin MG, MHF meat hydrolysate obtained using Flavourzyme 500 MG, MHN meat hydrolysate obtained using Neutrase 0.8 L, MHP meat hydrolysate obtained using Protamex. R unhydrolyzed roe, RHA roe hydrolysate obtained using Alcalase 2.4 L, RHC roe hydrolysate obtained using Collupulin MG, RHF roe hydrolysate obtained using Flavourzyme 500 MG, RHN roe hydrolysate obtained using Neutrase 0.8 L, RHP roe hydrolysate obtained using Protamex. The results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates

Alcalase 2.4 L is an endopeptidase produced from a select strain of Bacillus licheniformis. The serine protease, subtilisin A, is its main enzymatic component, and the specific activity is 2.4 unit per gram. The optimum condition of hydrolysis has a very wide range of temperature (55–70 °C) and pH (6.5–9.5); thus, it has been observed to be most effective in fish protein hydrolysis and antioxidant peptide production from shrimp [14], herring [15], Pacific whiting [16], and sardinella [11]. However, the optimal conditions can be different depending on the type of substrates. Collupulin MG (or papain) is an extract of papaya that possesses proteolytic activity. It is a type of microgranule capable of breaking the peptide bonds in basic amino acids, such as leucine and glycine [17]. In addition, Collupulin MG is widely used in the food industry because of its excellent water solubility. Ren et al. [18] showed that grass carp protein hydrolysate obtained using papain has higher antioxidant activity compared with the hydrolysate obtained using Alcalase. In addition, Je et al. [19] demonstrated that the hydrolysate of tuna backbone prepared via papain digestion exhibits higher DPPH radical scavenging activity compared with the hydrolysate obtained using Alcalase, α-chymotrypsin, Neutrase, pepsin, or trypsin. These results suggest that enzyme type is an important factor in determining the antioxidant activity of crude hydrolysate. This is because the amino acid composition of hydrolysates produced via proteolysis depends on the specific enzyme used.

Effect of pH value

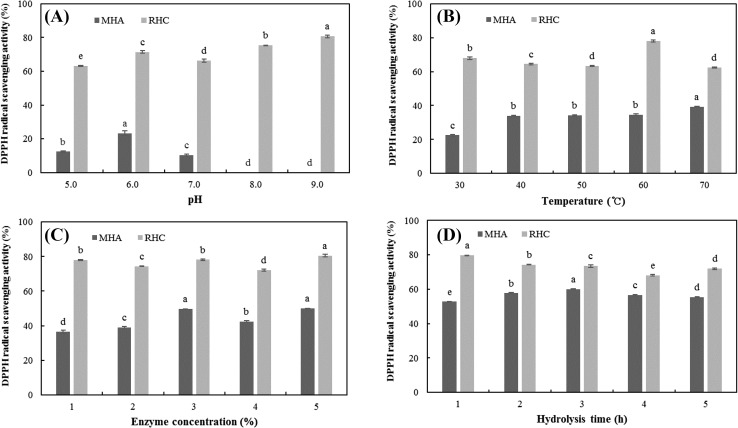

To determine the optimal pH for preparing MHA and RHC with the strongest radical scavenging activity, the samples were hydrolyzed at various pHs and the radical scavenging activity of each hydrolysate was measured [Fig. 2(A)]. The highest radical scavenging activity of MHA was 23.31% at pH 6.0, and the strongest radical scavenging activity of RHC was 80.72% at pH 9.0. Therefore, MHA and RHC were prepared by adjusting the pH to 6.0 and 9.0, respectively. Guerard et al. [20] demonstrated that pH significantly affects radical scavenging activity during the hydrolysis of shrimp processing discards. In addition, Zhuang et al. [21] reported that pH significant affects radical scavenging activity in the hydrolysate obtained from jellyfish umbrella collagen. Similarly, the present study confirmed that DPPH radical scavenging activities significantly differ in response to changes in pH. However, any correlation found between radical scavenging activity and pH was irregular.

Fig. 2.

DPPH radical scavenging activity of the hydrolysates according to different (A) pH, (B) temperature, (C) enzyme concentration, and (D) hydrolysis time. MHA meat hydrolysate obtained using Alcalase 2.4 L, RHC roe hydrolysate obtained using Collupulin MG. The results are expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicates. Values with different letters in the same sample are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Effect of temperature

Appropriate temperature promotes hydrolysis by increasing the enzymatic activity, the degree of hydrolysis (DH), and, in turn, the hydrolysis yield. However, proteins or peptides are denatured because of many physical factors, such as heat, cold, desiccation, mechanical agitation, and pH. In particular, denaturation via heating leads to disruption of the native peptide structure and loss of its biological activity [22, 23]. Accordingly, we obtained hydrolysate with the highest radical scavenging activity by determining the antioxidant activity of hydrolysate in response to temperature. The strongest radical scavenging activity of 39.22 and 78.03% were observed in MHA hydrolyzed at 70 °C and RHC hydrolyzed at 60 °C, respectively [Fig. 2(B)]. Consequently, MHA and RHC were prepared via hydrolysis at temperatures of 70 and 60 °C, respectively.

Effect of enzyme concentration

To determine the optimal enzyme concentration for producing MHA and RHC with the strongest DPPH radical scavenging activity, the samples were hydrolyzed by adding various enzyme concentrations and the scavenging activity of each hydrolysate was measured [Fig. 2(C)]. For MHA, the highest radical scavenging activity of 49.88% occurred when the hydrolysate was prepared with a 5% enzyme concentration. This was not significantly different from the hydrolysate prepared with an enzyme concentration of 3% (p > 0.05); however, it was remarkably different from the hydrolysates obtained using enzyme concentrations of 1, 2, and 4%. For RHC, the peak radical scavenging ability of 80.53% was achieved when the hydrolysate was prepared with a 5% enzyme concentration. Therefore, both MHA and RHC were prepared using a 5% enzyme concentration. These results were consistent with those of a previous study in which the antioxidant activity markedly changed depending on the hydrolytic conditions, e.g., the substrate-enzyme ratio [24].

Effect of hydrolysis time

To determine the optimal hydrolysis time for producing MHA and RHC with the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity, the samples were hydrolyzed for different lengths of time and the radical scavenging activity of each hydrolysate was measured [Fig. 2(D)]. The radical scavenging activity of MHA increased with time until the 3 h time point, after which it began to decline. The strongest radical scavenging activity of 60.04% was observed in the hydrolysate collected at the 3 h time point. For RHC, the highest radical scavenging ability of 79.65% was observed in the hydrolysate collected at the 1 h time point. The DPPH radical scavenging activity for RHC decreased with time; however, a slight increase in activity was observed after 5 h. Therefore, MHA and RHC were hydrolyzed for 3 and 1 h, respectively. Kong and Xiong [25] indicated that the radical scavenging activity of zein protein hydrolysate was impervious to hydrolysis time. However, Dong et al. [26] and Peng et al. [27] demonstrated that the antioxidant activity of silver carp and whey protein hydrolysate increased in response to hydrolysis time, respectively. Wu et al. [28] also reported that the DPPH radical scavenging activity of mackerel hydrolysate increased in response to longer hydrolysis times. Similarly, the results of the present study indicate that the radical scavenging activity is dependent on hydrolysis time and type of substrate.

Furthermore, the results of the present study determined the optimal hydrolysis conditions for the preparation of hydrolysate derived from A. japonicus meat and roe (Table 2). The antioxidant activity of MHA was the strongest when it was prepared using a pH of 6.0, a hydrolysis temperature of 70 °C, an enzyme concentration of 5%, and a hydrolysis time of 3 h. The antioxidant activity of RHC was the strongest when it was prepared using a pH of 9.0, a hydrolysis temperature of 60 °C, an enzyme concentration of 5%, and a hydrolysis time of 1 h. Under the optimal hydrolysis conditions, the DPPH radical scavenging activities of MHA and RHC were 60.04 and 79.65%, respectively, which were higher than those of the hydrolysates obtained under control conditions. These results provide fundamental data for the production of hydrolysates with high radical scavenging activity and of antioxidant peptides from sandfish protein hydrolysates.

Table 2.

Optimal hydrolysis conditions for the preparation of hydrolysates derived from meat and roe of A. japonicus

| Optimal conditions | DPPH radical scavenging activity (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | Temperature (°C) | Enzyme concentration (%) | Hydrolysis time (h) | ||

| Meat | 6.0 | 70 | 5 | 3 | 60.04 ± 0.32a |

| Roe | 9.0 | 60 | 5 | 1 | 79.65 ± 0.16 |

aThe results are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 2017 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zaveri NT. Green tea and its polyphenolic catechins: medicinal uses in cancer and noncancer applications. Life Sci. 2006;78:2073–2080. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rani V, Deep G, Singh RK, Palle K, Yadav UC. Oxidative stress and metabolic disorders: pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies. Life Sci. 2016;148:183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liceaga-Gesualdo AM, Li-Chan ECY. Functional properties of fish protein hydrolysate from herring (Clupea harengus) J. Food Sci. 1999;64:1000–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb12268.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bougatef A, Nedjar-Arroume N, Manni L, Ravallec R, Barkia A, Guillochon D, Nasri M. Purification and identification of novel antioxidant peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of sardinelle (Sardinella aurita) by-products proteins. Food Chem. 2010;118:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang HL, Liceaga AM, Yoon KY. Purification, characterisation and stability of an antioxidant peptide derived from sandfish (Arctoscopus japonicus) protein hydrolysates. J. Func. Foods. 2016;20:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu R, Wang M, Duan JA, Guo JM, Tang YP. Purification and identification of three novel antioxidant peptides from Cornu Bubali (water buffalo horn) Peptides. 2010;31:786–793. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Zhang H, Wang L, Guo X, Wang X, Yao H. Isolation and identification of antioxidative peptides from rice endosperm protein enzymatic hydrolysate by consecutive chromatography and MALDI-TOF/TOF MS/MS. Food Chem. 2010;119:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SI, Yang JH, Yoon SC, Chun YY, Kim JB, Cha HK, Choi YM. Biomass estimation of sailfin sandfish, Arctoscopus japonicus. Korean waters. Kor. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2009;42:487–493. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang HL, Liceaga AM, Yoon KY. Isolation and characteristics of anti-inflammatory peptides from enzymatic hydrolysates of sandfish (Arctoscopus japonicus) protein. J. Aquat. Food Prod. T. 2017;26:234–244. doi: 10.1080/10498850.2016.1221015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senphan T, Benjakul S. Comparative study on virgin coconut oil extraction using protease from hepatopancreas of pacific white shrimp and Alcalase. J. Food Process. Pres. 2016;41:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souissi N, Bougatef A, Triki-Ellouz Y, Nasri M. Biochemical and functional properties of sardinella (Sardinella aurita) by-product hydrolysates. Food Technol. Biotech. 2007;45:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gülçin İ, Alici HA, Cesur M. Determination of in vitro antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of propofol. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:281–285. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koleva II, van Beek TA, Linssen JP, Groot AD, Evstatieva LN. Screening of plant extracts for antioxidant activity: a comparative study on three testing methods. Phytochem. Analysis. 2002;13:8–17. doi: 10.1002/pca.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang GR, Zhao J, Jiang JX. Effect of defatting and enzyme type on antioxidative activity of shrimp processing byproducts hydrolysate. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2011;20:651–657. doi: 10.1007/s10068-011-0092-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyle NT, Merritt JH. Quality of fish protein hydrolysates from herring (Clupea harengus) J. Food Sci. 1994;59:76–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1994.tb06901.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjakul S, Morrissey MT. Protein hydrolysates from Pacific whiting solid wastes. J. Agr. Food Chem. 1997;45:3423–3430. doi: 10.1021/jf970294g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menard R, Khouri HE, Plouffe C, Dupras R, Ripoll D, Vernet T, Tessier DC, Lalberte F, Thomas DY, Storer AC. A protein engineering study of the role of aspartate 158 in the catalytic mechanism of papain. Biochemistry. 1990;29:6706–6713. doi: 10.1021/bi00480a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ren J, Zhao M, Shi J, Wang J, Jiang Y, Cui C, Kakuda Y, Xue SJ. Optimization of antioxidant peptide production from grass carp sarcoplasmic protein using response surface methodology. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2008;41:1624–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Je JY, Qian ZJ, Byun HG, Kim SK. Purification and characterization of an antioxidant peptide obtained from tuna backbone protein by enzymatic hydrolysis. Process Biochem. 2007;42:840–846. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guerard F, Sumaya-Martinez MT, Laroque D, Chabeaud A, Dufossé L. Optimization of free radical scavenging activity by response surface methodology in the hydrolysis of shrimp processing discards. Process Biochem. 2007;42:1486–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhuang YL, Zhao X, Li BF. Optimization of antioxidant activity by response surface methodology in hydrolysates of jellyfish (Rhopilema esculentum) umbrella collagen. J. Zhejiang Univ-SC B. 2009;10:572–579. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0920081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell LN. Peptide stability in solids and solutions. Biotechnol. Progr. 1997;13:342–346. doi: 10.1021/bp970057y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell LN, Labuza TP. Aspartame degradation kinetics as affected by pH in intermediate and low moisture food systems. J. Food Sci. 1991;56:17–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb07964.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahidi F, Zhong Y. Bioactive peptides. J. AOAC Int. 2008;91:914–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kong B, Xiong YL. Antioxidant activity of zein hydrolysates in a liposome system and the possible mode of action. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2006;54:6059–6068. doi: 10.1021/jf060632q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong S, Zeng M, Wang D, Liu Z, Zhao Y, Yang H. Antioxidant and biochemical properties of protein hydrolysates prepared from Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) Food Chem. 2008;107:1485–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng X, Xiong YL, Kong B. Antioxidant activity of peptide fractions from whey protein hydrolysates as measured by electron spin resonance. Food Chem. 2009;113:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu HC, Chen HM, Shiau CY. Free amino acids and peptides as related to antioxidant properties in protein hydrolysates of mackerel (Scomber austriasicus) Food Res. Int. 2003;36:949–957. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(03)00104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]