Abstract

Introduction: An all-of-society approach to disaster risk reduction emphasizes inclusion and engagement in preparedness activities. A common recommendation is to promote household preparedness through the preparation of a ‘grab bag’ or ‘disaster kit’, that can be used to shelter-in-place or evacuate. However, there are knowledge gaps related to how this strategy is being used around the world as a disaster risk reduction strategy, and what evidence there is to support recommendations.

Methods: In this paper, we present an exploratory study undertaken to provide insight into how grab bag guidelines are used to promote preparedness in Canada, China, England, Japan, and Scotland, and supplemented by a literature review to understand existing evidence for this strategy.

Results: There are gaps in the literature regarding evidence on grab bag effectiveness. We also found variations in how grab bag guidelines are promoted across the five case studies.

Discussion: While there are clearly common items recommended for household grab bags (such as water and first aid kits), there are gaps in the literature regarding: 1) the evidence base to inform guidelines; 2) uptake of guidelines; and 3) to what extent grab bags reduce demands on essential services and improve disaster resilience.

1.0 Introduction

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 advocates an all-of-society approach toward disaster risk reduction (DRR). This approach recognizes the importance of engagement - across all levels of society - in preparedness activities, including action toward household preparedness1.

Household preparedness recommendations are typically oriented toward encouraging people to prepare their households; for self-sufficiency during and after a disaster for at least three days. Grab bags, which can be used to shelter-in-place or evacuate, are commonly recommended as a preparedness strategy2. The rationale for recommending assembly of grab bags, is emergency services may not reach everyone within the first 72 hours after an adverse event3. A bag of essentials may support self-sufficiency, and ensure the needs of people in a household are met while services are recovering from disruptions. In literature and practice, this type of bag is referred to by different names, including disaster emergency supply kits, disaster preparedness kits, go bags and grab bags. But what is the evidence they work? And how are grab bag recommendations promoted in different parts of the world?

As a first step toward addressing these questions, we present an exploratory study designed to provide insight into how grab bag guidelines are used to promote preparedness in Canada, China, England, Japan, and Scotland, supplemented with a literature review focused on existing research evidence for this DRR strategy. Our objective is to provide an overview of different practices, in combination with existing literature, to inform future research agendas in this area.

2.0 Methods

This study is comprised of two parts: the first is a literature review of grab bag guidelines and supporting research evidence and the second is a five-country case study of approaches used to promote grab bags for household preparedness.

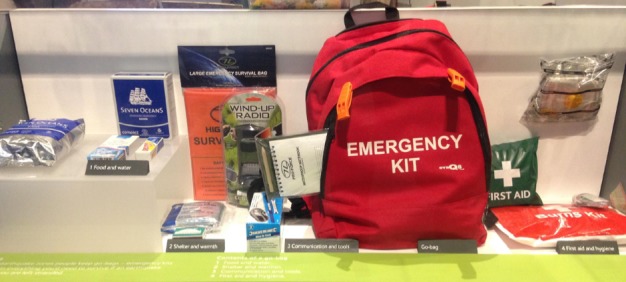

For the literature review, peer reviewed publications and grey literature 2006-2016 were searched using two databases (Embase and Scopus), as well as Google. Keywords included: emergency supply kit; emergency kit; go bag; grab bag; disaster supply kit; disaster emergency kit; emergency preparedness kit; disaster; emergency; hazards; evidence; emergency preparedness; resilience; and community resilience. The inclusion criteria were: 1) published in English, 2) focus on household preparedness, and 3) reference to grab bags. We did not include studies focused on general preparedness, or grab bag guidelines specific to pets, businesses and communities. The articles were reviewed and summarized by two co-authors (CP, TO), with emphasis on terminology, evidence of evaluation, and content of grab bags. See Appendix for database search strategies and a summary of search results by database.

The five-country case study included a comparison of approaches used to promote grab bags as a household preparedness strategy. Interns from Canada, China, and Japan, working at Public Health England, conducted research focused on their own countries and England, to contribute to an exchange of preparedness practices. Scotland was included for its novel approach in the establishment of a National Centre for Resilience (NCR).

3.0 Results

The results are presented in two parts.

3.1 Summary of the literature After removal of duplicates, a total of 38 articles which met the inclusion criteria were included in the literature review. Of these, seven articles were outside the scope of the study, resulting in a final sample of 31 articles. Table 1 summarises the articles included.

Of the 31 articles reviewed, 22 used grab bags as a measure of disaster preparedness. Most of these articles used survey methods to assess population preparedness, using indicators such as having a grab bag and an emergency plan. Facilitators and barriers were commonly discussed, with references to action by different demographics (eg. age, gender, marital status, education).

Bagwell et al.4, Crawford and McAlister5, Jassempour et al.6, Kettunen et al.7, Kohn et al.8, Kruvand and Bryant9, and Mack et al.10 evaluated preparedness before and after implementation of community preparedness programs. These studies highlighted techniques and tools with potential to improve awareness and action (eg. preparation of a grab bag or emergency plan). While grab bags were not specifically evaluated, the importance of evaluation for preparedness programs was emphasized.

Five studies investigated medication and medical supplies as important items for a grab bag11 ,12, 13, 14, 15. The specific needs of high-risk populations are important considerations. Kleinpeter et al.13 described the complications that arose for peritoneal dialysis patients after evacuating New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. Complications regarding storage of stockpiled medication included temperature control and expiration dates. This type of information is important for understanding the specific needs of populations living with chronic conditions, who may be at heightened risk during disasters.

Nine articles did not focus on grab bags as a measure of preparedness, instead they emphasized content and effectiveness of grab bags16 , 17, disaster preparedness18, post-disaster narratives13, 19, medical supplies and preparedness11, 13, 14, and preparedness interventions10,20. The different research methods, strategies, and approaches to study household preparedness were identified.

Perman et al.16 and Heagele17 discussed grab bags in terms of the evidence for effectiveness and variations in guidelines offered to the public. Perman et al.16 examined the contents of 71 guidelines on recommended items and stated that overly comprehensive lists can be overwhelming, whereas simple lists can be inadequate, calling for a standard for grab bag guidelines including empirical evidence on which items best support resilience. Heagele17 reviewed the literature on grab bag guidelines and found a lack of empirical evidence on how they support resilience. Heagele17 nevertheless reiterated the importance of continuing to promote grab bags as a preparedness strategy – given their potential to support households needing to be self-sufficient until help arrives. This is particularly important for high risk populations who must tailor the grab bags to ensure they have supplies to meet their unique needs.

Table 1: Summary of articles.

| Authors | Purpose of the articles | Focus on grab bags | Terminology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annis, Jacoby, & DeMers21 | Evaluate preparedness among US Navy personnel | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Disaster kit; Emergency kit; Emergency preparedness kit; Emergency supplies kit |

| Goodhue et al.22 | Evaluate preparedness of families with children in an intestinal rehabilitation clinic | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; How many households have a grab bag versus individual items; Extra supplies for children with special needs | Emergency supply kit; Disaster kit; Disaster survival kit |

| Heagele17 | Review evidence on effectiveness of grab bags used in household preparedness in the US | Inconsistent reporting; Lack of evidence on effectiveness; Lack of literature on how grab bags items are determined;Facilitators and barriers to preparing grab bags | Disaster preparedness kit; Disaster supply kit |

| Kruvand & Bryant9 | Examine whether the CDC* zombie apocalypse campaign translated to preparedness knowledge/ behaviour in youth | Intention to assemble a grab bag used as a measure of preparedness; Strategies to educate youth | Emergency kit |

| Ochi et al.14 | Make recommendations on effective preparedness based on a systematic review of medication loss in disasters | Specific items to be included in grab bags: medications and medical aids | Emergency pack; Emergency kit |

| Tanner & Doberstein23 | Examine the level of emergency preparedness among University students | Grab bags and individual components used as a measure of preparedness | Emergency preparedness kit; Emergency kit |

| Thomas et al.24 | Report on outcomes of CDC employees participating in Ready CDC | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Emergency kit |

| USAID19 | Report on how grab bags increased earthquake preparedness in Nepal | Woman’s experience using a grab bag after earthquake was effective | Go bag; Disaster preparedness kit; Emergency kit |

| Witvorapong, Muttarak & Pothisiri25 | Examine determinants of and relationships between social participation and disaster preparedness | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Emergency kit |

| Asada et al.11 | Survey pharmaceutical patients about preparedness and preservation of medication lists during a disaster | Discusses medication preparation and preservation for diabetes; Suggests keeping a medication lists | Emergency bag |

| Bagwell et al.4 | Assess preparedness of families of children with special healthcare needs and the impact of education and interventions | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Participants received backpack with first aid supplies and flashlights | Disaster kit |

| Chan et al.26 | Examine if previous disaster experience increases household preparedness in a village in China | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Disaster Emergency kit; Disaster kit |

| Jassempour et al.6 | Evaluate the effectiveness of applying a PAPM*-based disaster preparedness education program by focusing on uptake or creation of survival kits | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Measured level of awareness of grab bags and contents | Disaster survival kit |

| Kohn et al.8 | Measure outcomes of a personal preparedness curriculum for public health workers | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Linking dissemination with improved uptake; Discussed barriers and facilitators to preparedness behaviours | Emergency kit; Supply kit; Emergency preparedness kit; Preparedness kit |

| McCormick et al.27 | Examine the effects of experiencing a tornado on preparedness awareness and personal preparedness | Grab bags and individual grab bag items used as a measure of preparedness pre- and post-tornado | Preparedness kit; Disaster preparedness kit; Emergency preparedness kit; Disaster kit |

| Gershon et al.28 | Characterize preparedness for persons with disabilities, determine the role of the personal assistant and the impact of prior emergency experience on preparedness | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Populations changed contents of grab bags after experiencing a disaster | Go-bag; Grab bag |

| McCormick, Pevear & Xie29 | Evaluate the level of preparedness of residents and ‘at-risk’ residents, using the mass media personal preparedness ‘Get10’ campaign recommendations | Grab bags and individual grab bag items used as a measure of preparedness | Disaster kit; Preparedness kit; Disaster preparedness kit |

| Burke, Bethel, & Foreman Britt30 | Assess knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about disaster preparedness among Latino migrant and seasonal workers in North Carolina. | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Emergency kit |

| Loke, Lai & Fung31 | Explore the extent of disaster preparedness and concerns about disasters among the elderly in Hong Kong | Individual grab bag items used as a measure of preparedness | Survival pack; Emergency survival kit; Supplies kit |

| Tomio, Sato & Mizumura15 | Describe disaster preparedness among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and examine how differences in health, functional, and disability conditions are associated with disaster preparedness | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Focus on medications and medical records as a measure of medical preparedness | Emergency pack |

| Iannucci20 | Create a prototype person-centered program that individualizes preparedness for persons living in poverty with a disability | Abstract only. Identify and evaluate items needed for a tailored grab bag | Emergency kit; Preparedness kit |

| Perman et al.16 | Compare content guidelines for 71 grab bag guidelines in US | Analysis of comprehensiveness and specificity of grab bag guidelines | Disaster kit |

| Schmidt et al.32 | Explore perceptions of personal and program preparedness of nursing students | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness | Disaster kit; Go bag |

| Semenza, Ploubidis & George33 | Explore whether the health frame can act as a motivating factor for climate change adaptation behaviour to reduce climate risks | Grab bags used as a measure of climate change adaptation | Emergency kit |

| Crawford & McAlister5 | Prepare a high-risk population for disaster | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Distributed 3000 grab bags | Go-bag |

| Kettunen et al.7 | Evaluate educational efforts of a pandemic preparedness committee and assess community readiness | Grab bags used as a measure of pandemic preparedness | Emergency kit |

| Feret & Bratberg12 | Assess views of preparation and readiness of assisted-living residents after participating in a preparedness program | Grab bags used as a measure of preparedness; Focus on medical information and supplies | Disaster kit; Emergency preparedness kit; Emergency kit |

| Department of Homeland Security18 | Update and summarize current citizen preparedness research | Comparison of grab bag surveys from 2005-2007; Review of studies using grab bags as a measure of preparedness | Disaster supply kit; Emergency preparedness kit; Go bag; Disaster kit; Emergency supply kit |

| Kleinpeter, Norman & Krane13 | Describe disaster planning, implementation, and follow-up that occurred in a PD* program after Hurricane Katrina | Patients told to bring 1 week of PD supplies. No other grab bag contents specified | Disaster kit |

| Mack et al.10 | Introduce a curriculum that prepares low-income, low-resource families to survive disaster | Discusses barriers to grab bag assembly; Emphasizes need for items for children and culturally diverse food lists | Disaster kit; Safety kit; Disaster preparedness kit; Preparedness kit; Disaster survival kit |

| McRandle34 | Provide tips and environmentally sensitive solutions to help people manage in a disaster | Discusses items to include and the need to check items regularly | Emergency kit |

*Abbreviations: CDC= Centre for Disease Control; PAPM= Precaution Adoption Process Model; PD= Peritoneal dialysis

3.2 Summary of the five-country case studies The five country case studies, explored grab bag guidelines in Canada, China, England, Japan, and Scotland. The institution of origin for grab bag guidelines and recommendations varies across each country. In Canada, Japan, and Scotland, grab bag guidelines and recommendations stem from national government through Public Safety Canada, the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA), and Ready Scotland, respectively. In China, grab bag guidelines and recommendations occur through an academic institution from the Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster & Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC). In England, grab bag guidelines and recommendations are the responsibility of individual local authorities through Local Resilience Forums (LRFs) such as the Coventry, Solihull and Warwickshire (CSW) Resilience Team. These sources and their grab bag guidelines were explored in each country.

3.2.1 Canada In Canada, disaster preparedness is coordinated at a national level by Public Safety Canada35. Their website includes guidelines on what to include and the use of grab bags. This is an integral part of an ongoing campaign called ‘72 Hours… Is Your Family Prepared?’ that encourages households to be prepared to be self-sufficient for at least 72 hours after an adverse event3. In addition to grab bag guidelines, the campaign includes tips on knowing the risks in your community, and making a household emergency plan. A video explains how to assemble household grab bags and includes an interactive checklist. The 72 Hour campaign also provides a specialised grab bag guideline for persons with disabilities, who may have specific needs in an adverse event.

Public Safety Canada designates grab bags as emergency kits. The following is a list of items suggested: water, food, a manual can opener, wind-up battery-powered flashlights, a radio with extra batteries, first aid kit, extra keys for the car and house, cash, travelers’ cheques and change, and important family documents (e.g. identification, insurance, bank records, a copy of the household emergency plan, and contact information)36. Additional supplies to consider are: water for cooking and cleaning, personal hygiene items, hand sanitizer, toilet paper, prepaid phone card, mobile phone charger, pet food, infant formula, baby food and supplies, prescription medications, medical equipment, a whistle, and duct tape36. Within both lists, there are justifications for items included and website links are included for organizations that have grab bags available for purchase (e.g. St. John Ambulance, Salvation Army, and the Canadian Red Cross).

In addition to publications, the 72 Hour Preparedness campaign uses a range of dissemination techniques through promotional materials, social media, advertising, exhibits and special events, such as the annual Emergency Preparedness Week in May3. According to the Government of Canada3, the Get Prepared website has been visited 3 million times since its launch in 2006.

Other organizations in Canada that provide online guidelines for preparing grab bags are the Canadian Red Cross, Scouts Canada, Girl Guides Canada, and individual provincial/territorial governments and municipalities. Of note, the quantity and types of items suggested varies by organization, with some commonalities, such as water and food. There are extensive guidelines from organizations within Canada describing items to include in household grab bags and how they might be used, however there are inconsistencies, particularly in terminology. For example, the Canadian Red Cross calls them disaster preparedness kits37, while Emergency Management Ontario refers to them as emergency survival kits38.

While all organizations utilize their websites to disseminate disaster preparedness information, some are more proactive at communicating to the public. The Canadian Red Cross (@redcrosscanada) and Public Safety Canada (@Get_Prepared) for example, use Twitter to promote preparedness. Additionally, The Canadian Red Cross created a preparedness app called ‘Be Ready’ which aims to spread awareness of the importance of preparedness while giving people a tool to help prepare for and act in a disaster39.

3.2.2 China The CCOUC was established by the joint effort of Oxford University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong as a non-profit research centre. One of its core missions is to provide knowledge transfer and community service to enhance preparedness among communities facing disaster threats in Greater-China and the Asia-Pacific region40. Their Ethnic Minority Health Project (EMHP) is an initiative that highlights the work of CCOUC in disaster preparedness41. In China, there are no governmental level guidelines on using grab bags, therefore CCOUC works to fill this gap by providing information about household grab bags, with support from local health authorities, such as the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and village heads and village doctors. CCOUC advocates for the preparation and use of grab bags to minimize negative health impacts of natural disasters, whilst EMHP targets ethnic minorities residing in remote, poor, and disaster-prone areas.

Recommendations for grab bags, prepared by CCOUC in 2009, are based on the main protection principles highlighted by the Sphere Handbook42. The recommendations address basic survival needs for health, and the unique environmental constraints of rural areas in China. These include: a) water, sanitation and hygiene, b) food and nutrition, c) shelter and non-food items, d) healthcare and e) access to information. All items contained in the grab bag can be adapted to various hazard and disaster contexts. For example, the multi-purpose knife serves various functions (e.g. can opener, cutter, direction indicators) and the flint, apart from lighting a fire, can send signals allowing relief workers to locate victims43.

CCOUC emphasizes that decisions regarding what to include in a grab bag be based on public health principles and individual needs. For example, it is important to consider the special needs of patients living with chronic conditions44 and/or those who have lower literacy skills. CCOUC asks patients to take pictures of the medications they are currently taking; this helps ensure relief workers can efficiently and accurately identify medications people are taking and support patient safety. Regarding information and communication, CCOUC encourages villagers to keep a family portrait, a list of emergency contact information, and a copy of all the identification documents for each of the family members as part of their household grab bag. The family portrait and emergency contact information are particularly useful to support communication among people with low literacy skills. Having a copy of identification documents is useful if evacuation is required, health services are needed, and original documents are inaccessible43. To ensure villagers have a clear understanding of the importance and use of grab bags, CCOUC distributes grab bags in the EMHP sites and provides education on how to prepare, adapt, make accessible and use them according to local context43. Figure 1 provides an example of the grab bag and grab bag contents distributed to rural villages in China by CCOUC.

Grab bag and contents distributed to rural villages in China by CCOUC.

Picture taken by co-author (GKWC) and may be published under the CC-BY license with permission from the copyright holder (GKWC), original copyright 2016.

3.2.3 England In England (and the United Kingdom) emergency preparedness is primarily governed by the 2004 Civil Contingencies Act (CCA). This places duty on several agencies to prepare for and assist the public in preparing for emergencies, such as widespread flooding. The first publication to include a reference to an emergency grab bag was the leaflet Protect and Survive45.

In 2004, the Government produced and sent a leaflet to all residents46 that detailed actions to be taken in the event of an emergency, and included a list of suggested contents for a household grab bag. These suggested contents included: a list of useful phone numbers; home and car keys; toiletries, sanitary supplies and regularly prescribed medication; a battery radio and a torch with spare batteries; candles and matches; a First Aid kit; a mobile phone; cash and credit cards; spare clothes and blankets; bottled water, ready-to-eat food and a bottle/tin opener. This list has remained effectively the same for the past decade, but with added emphasis on tailoring the contents for individual needs (e.g. specific supports for children, older people, persons living with disabilities and pets).

The use of grab bags is now currently promoted locally. For example, an LRF, based in Bedfordshire (BLRF), uses Twitter (@what_would)47 to engage with the community and re-tweets examples of grab bag good practices from around the country including Merseyside48 and Essex49. Another LRF in Coventry, Solihull and Warwickshire (CSW) use their website50 and Twitter account (@PreparedPics) to promote the use of grab bags with a series of tweets throughout June 201651 using the #GrabBag hashtag and went through recommended items for a grab bag in an informative, but light-hearted manner.

The way guidelines for grab bags are presented varies considerably across England. CSW uses a light-hearted manner across their website and Twitter presence with a family of cartoon characters based on crash test dummies to emphasise the points being made52. Essex has communicated the importance and use of grab bags through their “What If” initiative53. Local Resilience Fora use branding for all preparedness information and warnings, are actively promoting the use of grab bags, and strategically aligning all messaging for consistency and recognition. There are 38 LRFs in England. Each local fora has grab bag guidance, such as Bedfordshire54, however Essex and CSW are more prominent.

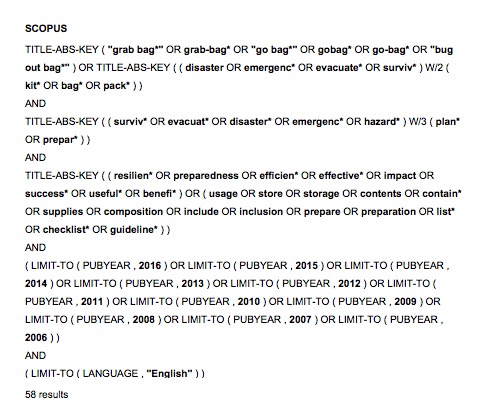

In London, a grab bag display can be found in the Natural History Museum, in their Volcanoes and Earthquakes Exhibition (see Figure 2). Using ‘go-bag’ as their terminology of choice, the simplistic and comprehensive display summarises the goal of grab bags: to provide food, water, shelter, warmth, communication, tools, first aid, and hygiene. The display includes physical examples of the items, such as a wind-up radio, waterproof notebook and the grab bag itself. The grab bag is defined in relation to people living in earthquake zones and can be found in the exhibit about the deadly 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

Go-bag display in the Volcanoes and Earthquakes Exhibition at the Natural History Museum in London, England.

Photo taken by the lead author (CJP) with permission from the Natural History Museum. Image may be published under the CC-BY license with permission from the copyright holder (CJP), original copyright 2018.

3.2.4 Japan In Japan, the FDMA, a subordinate body of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, oversees community education and interventions to promote disaster resilience. One DRR strategy used by this organization is to provide grab bag guidelines55.

The grab bag contents suggested by the FDMA55 include: a bankbook, flashlight, candles, gloves, radio, dry battery, cash, cigarette lighter, can opener, helmet, disaster hood (used as a cushion daily, or used as a hood), knife, baby bottle, food, blanket, clothes, first aid kit, and their signature stamp. It is common for the Japanese to use a signature stamp in formal documentation procedures. FDMA also provides a disaster survival handbook on their website as educational material providing detailed recommendations about grab bag contents. For example, diapers and sweaters as suggested clothes, and food, such as instant noodles, chocolates, and canned food56.

The FDMA handbook has various advantages. Firstly, it can be accessed electronically. Secondly, cartoon images are used in each chapter to make it easier to understand for people with limited literacy skills or for whom Japanese is not their first language. Only a limited portion of the official website is translated into English, therefore it would be difficult for people who cannot read Japanese to access the webpage.

3.2.5 Scotland Scotland is pursuing a multi-dimensional, ‘whole society’ approach to building resilient communities, which aims to make resilience everyone’s business, summarized in ‘Ready Scotland’57. This brings together a wide range of organisations in the public, private, voluntary sector organisations and other civil society groups in a collective effort to change the culture around resilience, and improve the ability of communities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from emergencies.

The Scottish approach is delivered through an assets-based community development approach by Scotland’s resilience community. This means providing individuals and groups of people with the knowledge and skills they need to effect change in their own communities, through a process of engagement, education, empowerment and encouragement58. The focus is on relatively simple ‘asks’ of individuals, organisations and communities, with the intention that they a) become more aware of risks, b) plan and take action toward preparedness, and c) cooperate with and help others. The public are encouraged to assemble grab bags to improve household resilience. In empowering self-sufficient citizens, this strategy allows the public to contribute to the resilience of their communities, allowing emergency response agencies to more accurately prioritize cases such as addressing the needs of high risk populations. The “Ready Scotland” website hosts advice on grab bag contents, and household emergency plan templates which include a checklist of items59. This advice has been taken up, adapted and used by a range of partner organisations.

The National Centre for Resilience (NCR) acts as a “hub” for the Scottish resilience community providing research, analysis and leadership in developing best practices. It facilitates shared outcomes and priorities in community resilience by supporting partners through design, delivery and dissemination of resources and toolkits such as grab bags60. The NCR is a catalyst for collaborations, by bringing together resilience partners on a network basis across diverse communities, including those in educational settings. Resilience education initiatives, in formal and informal settings, have adapted the grab bag concept to be more youth-friendly. For example an activity based around completing a “Family Emergency Plan”, which includes a grab bag checklist to be completed by families or in the classroom.

4.0 Discussion

This paper presents a literature review focused on the use of grab bags to promote household preparedness and five country case studies of grab bag promotion. Though the academic literature has identified a gap in empirical evidence for this DRR strategy, promotion of grab bags continues. Indeed the authors who contributed to featured case studies support grab bag strategies, recognizing the approach’s potential to save lives and reduce negative disaster impacts. This strategy reflects the precautionary principle; which stipulates that risk management action can be taken despite scientific uncertainty due to lack of evidence, to protect people from harm61. Based on this principle, we recommend that grab bags continue to be promoted as a household preparedness measure, but echo recommendations by Perman et al.16 and Heagele17 for an improved evidence base and development of good practice alongside its current use.

4.1 Evidence of grab bag effectiveness The Sendai Framework stresses engagement with its recommendations for an all-of-society approach to DRR1. The assembly of grab bags, tailored to the needs of individuals in a household, exemplifies activity that promotes discussion of preparedness and has the potential to move people toward action. Grab bags as a preparedness measure are promoted by many countries to reduce the risk of harm to a population in the face of a hazard and are assumed to influence resilience, but further evidence is needed to understand this role.

Two of the 31 articles reviewed explicitly provided information on the effectiveness of grabs bags for increasing community resilience. Heagele17 discusses the lack of evidence on the efficacy of grab bags and the need for further research to support assumptions of grab bags contribution to DRR. The author stipulates that it is important to investigate if and how grab bags are effective. A recent article from USAID19 includes testimony from a woman who used a grab bag during the deadly Nepal earthquake in April 2015 who discusses how the items helped her family survive post-disaster.

Research examining the effectiveness of grab bags as a preparedness behaviour would be beneficial to: 1) inform policy makers, government officials, and investors about the potential return of investment on promotional grab bag campaigns; 2) enhance motivation for grab bag preparation; and 3) improve knowledge about the most useful items to include in a grab bag. A research agenda should include qualitative methods to capture experiences of peoples’ use of grab bags. These methods could improve understanding of grab bags usage and how to move people from awareness to action; grab bags might also influence public confidence regarding whether preparedness actions will make a difference in a disaster18. An additional item for the research agenda is to explore mechanisms that contribute to uptake of grab bag recommendations, while also exploring different strategies to include households with limited means to assemble these types of kits.

4.2 Content of grab bags When using grab bags as a measure of preparedness, survey questions most often ask about having a grab bag, rather than individual items. However, Goodhue et al.22, Loke et al.31, McCormick et al.27 ,29, and Tanner and Doberstein23 inquired about specific types of supplies in the grab bag. This distinction provided insight not only about who possessed a grab bag, but also its comprehensiveness, and which items were easiest to acquire.

This literature review revealed that grab bags are an integral DRR strategy, and often used as an indicator for preparedness. The literature is predominantly quantitative, and focused on facilitators and barriers to preparedness at household and individual levels. The quantitative studies that examined grab bag use, by investigating completeness of grab bags compared to official guidelines, provide a base for future research. Qualitative and mixed methods studies are needed to better understand the role of grab bags in supporting community resilience.

4.2.1 Listing content for guidance In the case studies, guidelines varied according to the type of items and quantity. Some guidelines focused on portability, for utility in evacuation, whereas others included too many items to be realistically portable. This issue was identified by Perman et al.16 where some of the 71 checklists they compared discouraged action because they were overwhelming. Given that grab bags are promoted for both sheltering-in-place and evacuation, the need for realistic lists and evidence to support them is paramount.

4.2.2 Approaches to communication Another area of variability, noted in the five-country case study, is the accessibility of the grab bag guidelines and dissemination techniques. While all five countries utilize organizational websites to display grab bag guidelines, dissemination techniques vary. In Canada, grab bag promotion is incorporated into a larger preparedness campaign titled ‘72 Hours… Is Your Family Prepared?’ using a variety of strategies such as promotional material, social media, and special events3. In China, the CCOUC uses websites and leaflets to disseminate information on grab bags, while also using knowledge transfer initiatives such as the EMHP. Through EMHP, CCOUC distributes physical grab bags to some high risk populations. In Scotland, dissemination strategies include the ‘Ready Scotland’ campaign, flyers, and preparedness activities in schools. England and Japan use similar dissemination strategies using cartoons to add a fun and light-hearted tone to their message. In England, the CSW Resilience Team regularly uses Twitter to promote grab bag use using cartoon families. In Japan, the FDMA government website is home to information on grab bags and an electronic disaster survival handbook that uses cartoons and drawings of grab bag items to make the handbook more accessible for persons with lower literacy, or those who cannot read Japanese.

The five-country case study revealed promising practices to promote awareness and action. Empirical studies to understand the uptake of recommendations would enable organizations to invest in practices that have higher impact on behavioural outcomes. The literature has repeatedly shown that a small percentage of the population is prepared and has a formal grab bag ready18 ,22 ,31 ,32. Yet of those who have grab bags, many do not contain all the recommended items22 , 23 , 27 , 29. This underscores the need to evaluate dissemination and public interpretation of preparedness guidelines. A number of studies have started to address this gap, with evaluation of tools, programs and dissemination techniques for changes in knowledge and uptake of preparedness behaviours such as grab bag preparedness6 , 7 , 9 , 10.

4.3 Limitations This study provides insight from five-country case studies and a review of extant literature. While grab bag guidelines were explored across countries, the variation in terminology, contexts, and disaster risk sensitivities makes direct comparison challenging. The differences in contexts may explain inconsistencies in suggested items for inclusion in a grab bag. Expansion of this study to other countries, particularly developing countries, is recommended. Additionally, due to resource constraints, the literature review only searched two bibliographic databases and Google. A next step would be to expand the literature search to include other databases and languages.

5.0 Recommendations

The following recommendations are provided to address gaps in the literature on effectiveness of grab bags, and share promising practices in household preparedness strategies. This study supports the continued use, promotion, and preparation of grab bags, despite lack of evidence of effectiveness. To build an evidence-base, more research is needed to understand: 1) the evidence base that informs guidelines; 2) uptake of grab bag guidelines at the household level; and 3) to what extent grab bags can reduce demands on essential services and improve disaster resilience. Such research can provide insight on how to encourage public engagement in disaster preparedness practices and support community resilience processes.

Future research should also continue to examine dissemination techniques to ensure guidelines are reaching intended audiences and promoting positive change in preparedness behaviour. Tailored messaging will ensure the needs of different populations are included, particularly for households where there are limited means to assemble supplies.

Defined terminology is an important aspect for grab bag guidelines, the most common terms used were ‘disaster kit’, ‘emergency kit’, ‘disaster preparedness kit’, and ‘emergency preparedness kit’. Introducing standardized terms could help to minimize confusion and provide consistency for sharing information between countries and organizations. An additional recommendation is to add the term ‘grab bag’ to the glossary of terms provided by leading organisations in DRR such as the World Health Organization (WHO).

6.0 Conclusion

The results of this study identified gaps in the evidence on the effectiveness of grab bags, and found variations in guidelines and promotion practices across different countries. With the implementation of the Sendai Framework and its emphasis on an all-of-society approach to DRR1, there is an opportunity to raise widespread awareness of the importance of household preparedness. Grab bags are recognized as an important strategy to support DRR, however the need for an evidence base must be addressed to support investments in this area.

7.0 Appendix

Table 2: Embase search strategy.

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ("grab bag*" or grab-bag* or "go bag*" or GoBag* or go-bag* or "bug out bag*").tw. | 19 |

| 2 | ((disaster or emergenc*) adj2 (kit* or bag* or pack*)).tw. | 385 |

| 3 | 1 or 2 | 404 |

| 4 | ((surviv* or evacuat* or disaster* or emergenc* or hazard*) adj3 (plan* or prepar*)).tw. | 9931 |

| 5 | disaster/ or disaster planning/ | 21453 |

| 6 | 4 or 5 | 28499 |

| 7 | 3 and 6 | 46 |

| 8 | limit 7 to ((chinese or english or japanese) and yr="2006 -Current") | 39 |

| 9 | (us* or stor* or cont* or supplies or composition or inclu* or prepar* or list* or checklist* or guideline*).tw. | 12274294 |

| 10 | 8 and 9 | 37 |

| 11 | (effective* or resilien* or efficien* or benefi* or impact or success* or useful*).tw. | 4501740 |

| 12 | 8 and 11 | 19 |

Scopus search strategy.

Screenshot taken by the lead author (CJP). Image may be published under the CC-BY license with permission from the copyright holder (CJP), original copyright 2018.

Table 3: Summary of databases searched and results.

| Source | Results |

|---|---|

| EMBASE | 39 (27 relevant) |

| SCOPUS | 58 (22 relevant) |

| TOTAL (after removing duplicates) | 35 |

Corresponding Authors

Christina J. Pickering (cpick030@uottawa.ca) and Dr. Virginia Murray (Virginia.Murray@phe.gov.uk.)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.

Competing Interests Statement

I have read the journal’s policy and have the following conflicts to declare. The following co-authors of this manuscript are currently members of the Editorial Board for a PLOS Currents journal: Dr. Emily YY Chan, Dr. Tracey O'Sullivan, and Dr. Virginia Murray. The authors have no other competing interests to declare.

Biographies

Since joining the Scottish Government I have been leading on a number of key policy areas, including: justice; transport; fisheries; public services reform and the setting up of the new scrutiny bodies in Scotland; health and social care improvement. More recently I led the Scottish Government Response Team (SGoRR) and dealt with a number of emergencies and high profile incidents, including severe winter weather and the Clutha Vaults helicopter crash. I am currently the Natural Hazards policy lead for the Scottish Government Resilience Division, and also lead on the implementation and sponsorship of the National Centre for Resilience (NCR). I have experience of fast-paced and high profile areas as well as a high degree of stakeholder engagement, both internal and external to Government, often at senior level. I also represent the Scottish Government on the a number of UK-wide groups, including the Natural Hazards Partnership Steering Group, and the Public Weather Service Customer Group. I am a graduate of the University of Florence (Italy) where I studied law and I am a dual qualified and bilingual Italian/Scottish Solicitor and Notary Public. This was followed by a Master of Arts Degree in Social Policy and Criminology at The Open University-Scotland. I live and work in Edinburgh (Scotland - UK) with my husband and a young daughter. I also volunteer as a pro-bono solicitor supporting local communities

Head of Extreme Events and Health Protection, Public Health England, UK

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Contributor Information

Christina J. Pickering, Canada and Overseas Training Fellow, Public Health England, London, United Kingdom; Enhancing Resilience and Capacity for Health (EnRiCH) Research Lab, Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Canada

Tracey L. O'Sullivan, Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences and Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Alessia Morris, Scottish Government, Resilience Division, United Kingdom, Edinburgh, Midlothians, Scotland, UK.

Carman Mark, Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC), JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong S.A.R., China..

David McQuirk, Emergency Response Department, Health Protection and Medical Directorate, Public Health England, London, United Kingdom.

Emily YY Chan, Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC), JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong S.A.R., China; Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom; FXB Centre of Health and Human Rights, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Emily Guy, Interdisciplinary School of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Gloria KW Chan, Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC), JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong S.A.R., China..

Karen Reddin, Emergency Response Department, Health Protection and Medical Directorate, Public Health England, London, United Kingdom.

Ralph Throp, Resilience Division, Scottish Government, Edinburgh, Midlothians, Scotland, United Kingdom.

Shinya Tsuzuki, Health Science Division, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan; Tier 5 Intern, Public Health England, London, United Kingdom.

Tiffany Yeung, Hong Kong Jockey Club Disaster Preparedness and Response Institute, Hong Kong, China; Overseas Training Fellow for Healthcare Professionals, Public Health England, England, United Kingdom.

Virginia Murray, Public Health England, London, England; Integrated Research on Disaster Risk Scientific Committee, Beijing, China..

References

- 1.UNISDR (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction). 2015. Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015-2030. Geneva: UNISDR.

- 2.Codreanu, T., A. Celenza, and I. Jacobs. 2014. Does disaster education of teenagers translate into better survival knowledge, knowledge of skills, and adaptive behavioral change? A systematic literature review. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 29(6): 629–642. doi.10.1017/S1049023X14001083. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Government of Canada. 2015. The “72 Hours...Is Your Family Prepared?” campaign. Government of Canada: Get prepared. Date modified January 15. https://www.getprepared.gc.ca/cnt/bt/index-en.aspx.

- 4.Bagwell, H., R. Liggin, T. Thompson, K. Lyle, A. Anthony, M. Baltz, M. Melguizo-Castro, T. Nick, and D. Kuo. 2014. Improving disaster awareness and preparedness among families of children with special healthcare needs. Journal of Investigative Medicine 62(2): 511–512.

- 5.Crawford, J., and S. McAlister. 2010. Emergency preparedness in the bleeding disorders population. Haemophilia 16: 53–54.

- 6.Jassempour, K., K.K. Shirazi, M. Fararooei, M. Shams, and A.R. Shirazi. 2014. The impact of educational intervention for providing disaster survival kit: Applying precaution adoption process model. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 10 (Part A): 374–380. doi.10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.10.012.

- 7.Kettunen, C., J. Becker, K. McIntyre, C. Hill, S. Kennedy, C. Callahan, and B. Distelrath. 2009. Survey of community residents to assess readiness for a pandemic. American Journal of Infection Control 37(5): E33. doi.10.1016/j.ajic.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Kohn, S., N. Semon, H.K. Hedlin, C.B. Thompson, F. Marum, S. Jenkins, C.C. Slemp, and D.J. Barnett. 2014. Public health-specific personal disaster preparedness training: An academic-practice collaboration. Journal of Emergency Management 12(1): 55–73. doi.10.5055/jem.2014.0162. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kruvand, M., and F.B. Bryant. 2015. Zombie apocalypse: Can the undead teach the living how to survive an emergency? Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974) 130(6): 655–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Mack, S.E., D. Spotts, A. Hayes, and J.R. Warner. 2006. Teaching emergency preparedness to restricted-budget families. Public Health Nursing 23(4): 354–360. doi.10.1111/j.1525-1446.2006.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Asada, Y., T. Mori, C. Takayama, Y. Asahi, S. Morishita, H. Fujii, Y. Watanabe, Y. Kawagoe, A. Nonaka, and T. Miyakawa. 2014. How to preserve insulin? & what we learned from the energy-saving lifestyle after the disaster. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 106(Supplement 1): S80–S80. doi:10.1016/S0168-8227(14)70365-1.

- 12.Feret, B., and J. Bratberg. 2008. Pharmacist-based intervention to prepare residents of assisted-living facilities for emergencies. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 48(6): 780–783. doi.10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07068. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kleinpeter, M.A., L.D. Norman, and N.K. Krane. 2006. Disaster planning for peritoneal dialysis programs. Advances in Peritoneal Dialysis. Conference on Peritoneal Dialysis 22: 124–129. [PubMed]

- 14.Ochi, S., S. Hodgson, O. Landeg, L. Mayner, and V. Murray. 2015. Medication supply for people evacuated during disasters. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine 8(1): 39–41. doi.10.1111/jebm.12138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Tomio, J., H. Sato, and H. Mizumura. 2012. Disparity in disaster preparedness among rheumatoid arthritis patients with various general health, functional, and disability conditions. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine 17(4): 322–331. doi.10.1007/s12199-011-0257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Perman J, Shoaf K, Kourouyan A, and M Kelley. 2011. Disaster kit contents: a comparison of published guidelines for household preparedness supplies. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters. 29 (1). 1-25.

- 17.Heagele, T.N. 2016. Lack of evidence supporting the effectiveness of disaster supply kits. American Journal of Public Health 106(6): 979–982. doi.10.2105/AJPH.2016.303148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Department of Homeland Security. 2007. Citizen Preparedness Review No. 5: Update on citizen preparedness research. Accessed February 8, 2017. http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1910-25045-4658/citizen_prep_review_issue_5.pdf.

- 19.USAID (United States Agency for International Development). 2015. “Go bags” increase earthquake preparedness in Nepal. USAID News & Information. Last modified June 3. https://www.usaid.gov/results-data/success-stories/go-bags-increase-earthquake-preparedness-nepal.

- 20.Iannucci, M. 2011. Living at the intersection of disability and poverty is dangerous to one’s health: A person-centered approach to emergency preparedness. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom) 97: eS1519.

- 21.Annis, H., I. Jacoby, and G. DeMers. 2016. Disaster preparedness among active duty personnel, retirees, veterans, and dependents. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 31(2): 132–140. doi:10.1017/S1049023X16000157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Goodhue, C.J., N.E. Demeter, R.V. Burke, K.T. Toor, J.S. Upperman, and R.J. Merritt. 2016. Mixed-methods pilot study: Disaster preparedness of families with children followed in an intestinal rehabilitation clinic. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 31(2): 257–265. doi.10.1177/0884533615605828. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Tanner, A., and B. Doberstein. 2015. Emergency preparedness amongst university students. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 409–413. doi.10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.08.007.

- 24.Thomas, T.N., M. Leander-Griffith, V. Harp, and J.P. Cioffi. 2015. Influences of preparedness knowledge and beliefs on household disaster preparedness. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 64(35): 965–971. doi.10.15585/mmwr.mm6435a2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Witvorapong, N., R. Muttarak, and W. Pothisiri. 2015. Social participation and disaster risk reduction behaviors in tsunami prone areas. PLOS ONE 10(7): e0130862. doi.10.1371/journal.pone.0130862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chan, E.Y.Y., J.H. Kim, C. Lin, E.Y.L. Cheung, and P.P.Y. Lee. 2014. Is previous disaster experience a good predictor for disaster preparedness in extreme poverty households in remote Muslim minority based community in China? Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16(3): 466–472. doi.10.1007/s10903-012-9761-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.McCormick, L.C., J. Pevear, A. Rucks, and P. Ginter. 2014. The effects of the April 2011 tornado outbreak on personal preparedness in Jefferson County, Alabama. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 20(4): 424-31. doi.10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182a45104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gershon, R.R.M., L.E. Kraus, V.H. Raveis, M.F. Sherman, and J.I. Kailes. 2013. Emergency preparedness in a sample of persons with disabilities. American Journal of Disaster Medicine 8(1): 35–47. doi.10.5055/ajdm.2013.0109. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.McCormick, L.C., J. Pevear, and R. Xie. 2013. Measuring levels of citizen public health emergency preparedness, Jefferson County, Alabama. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 19(3): 266–273. doi.10.1097/PHH.0b013e318264ed8c. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Burke, S., J.W. Bethel, and A. Foreman Britt. 2012. Assessing disaster preparedness among Latino migrant and seasonal farmworkers in Eastern North Carolina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9(9): 3115–3133. doi:10.3390/ijerph9093115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Loke, A.Y., C.K. Lai, and O.W.M. Fung. 2012. At‐home disaster preparedness of elderly people in Hong Kong. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 12(3): 524–531. doi.10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Schmidt, C.K., J.M. Davis, J.L. Sanders, L.A. Chapman, M.C. Cisco, and A.R. Hady. 2011. Exploring nursing students’ level of preparedness for disaster response. Nursing Education Perspectives (National League for Nursing) 32(6): 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Semenza, J.C., G.B. Ploubidis, and L.A. George. 2011. Climate change and climate variability: Personal motivation for adaptation and mitigation. Environmental Health 10(1): 46. doi.10.1186/1476-069X-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.McRandle, P.W. 2006. Preparing for disasters. World Watch 19(5): 6–6.

- 35.Public Safety Canada. 2016. Emergency management. Government of Canada. Last modified May 10. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/mrgnc-mngmnt/index-en.aspx-.

- 36.Government of Canada. 2016. Get an emergency kit! Government of Canada: Get prepared. Last modified May 31. https://www.getprepared.gc.ca/cnt/kts/bsc-kt-en.aspx.

- 37.Canadian Red Cross. 2017a. For home and family: Get a kit. Canadian Red Cross. Accessed Feb 8. http://www.redcross.ca/how-we-help/emergencies-and-disasters-in-canada/for-home-and-family/get-a-kit.

- 38.Ontario MCSCS (Ontario Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services). 2016. Step 2: Build a kit. Emergency Management Ontario. Last modified May 25. https://www.emergencymanagementontario.ca/english/beprepared/Step2BuildAKit/Step2_build_a_kit.html.

- 39.Canadian Red Cross. 2017b. Emergencies and disasters in Canada: Be Ready app. Canadian Red Cross. Accessed Feb 9. http://www.redcross.ca/how-we-help/emergencies-and-disasters-in-canada/be-ready-app.

- 40.CCOUC (Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response). 2016a. About us: Introduction. CCOUC. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.ccouc.ox.ac.uk/introduction.

- 41.CCOUC (Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response). 2016b. Activities in China: Ethnic Minority Health Project. CCOUC. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.ccouc.ox.ac.uk/home-5.

- 42.The Sphere Project. 2011. Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response. The Sphere Project. Accessed February 10, 2017. http://www.spherehandbook.org/.

- 43.Chan, E.Y.Y., C.Y. Zhu, P.Y. Lee, and K.S.D. Liu. 2016. Training manual on health and disaster preparedness in rural China. Edited by E.Y.Y. Chan, K.W.K. Ling, C.S. Wong, K.S.D. Liu, and P.Y. Lee. CCOUC & WZQCF. Last modified February, 2016. http://ccouc.org/_asset/file/public-health-manual-eng-small.pdf.

- 44.Chan, E.Y.Y., and E. Sondorp. 2007. Medical interventions following natural disasters: Missing out on chronic medical needs. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health 19 Spec No: 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Home Office. 1980. Protect and survive. London: HM Stationary Office. Last modified June, 1999. http://www.atomica.co.uk/main.htm.

- 46.Cabinet Office. 2004. Preparing for emergencies: What you need to know. Accessed February 9, 2017. http://www.cheshirefire.gov.uk/Assets/preparingforemergencies.pdf.

- 47.BLRF (Bedfordshire Local Resilience Forum). 2017a. Media tweets by @what_would. Twitter. Accessed February 9. https://twitter.com/what_would?lang=en-gb.

- 48.Merseyside Resilience Forum. 2017. Preparing for emergencies in the North West. Merseyside Prepared. Accessed, February 10. http://www.merseysideprepared.org.uk/.

- 49.ECPEM (Essex Civil Protection and Emergency Management). 2016. Are you prepared for an emergency? Accessed February 8, 2017. http://media.wix.com/ugd/aacf38_0bf9dd8e78454f9bb9912b77cca65ab9.pdf.

- 50.CSW Council (Coventry, Solihull and Warwickshire Council). 2017a. Planning, preparing and responding to emergencies. CSW Resilience Team. Accessed February 9. http://cswprepared.org.uk.

- 51.CSW Resilience Team. 2016. Media tweets by @PreparedPics. Twitter. Accessed June, 2016. https://twitter.com/PreparedPics/media?lang=en-gb.

- 52.CSW Council (Coventry, Solihull and Warwickshire Council). 2017b. Prepare 4 action. CSW Resilience Team. Accessed February 9. http://cswprepared.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Be-Prepared-Home_Emergency_Plan.pdf.

- 53.ECPEM (Essex Civil Protection and Emergency Management). 2017. What If…? ECPEM. Accessed February 9. http://www.whatif-guidance.org/.

- 54.BLRF (Bedfordshire Local Resilience Forum). 2017b. Additional advice and tips for your family: Get ready- Get a kit. BLRF: What Would You Do If..? Accessed February 9. https://www.bllrf.org.uk/content/?id=163.

- 55.FDMA (Fire and Disaster Management Agency). 2017. Introduction of disaster prevention goods (防災グッズの紹介). Accessed February 9 (in Japanese). http://www.fdma.go.jp/html/life/sack.html.

- 56.FDMA (Fire and Disaster Management Agency). 2015. My disaster survival handbook (私の防災サバイバル手帳 watashi no bousai survival techou). Accessed February 9, 2017 (in Japanese). http://www.fdma.go.jp/html/life/survival/pdf/h27/survival2703_all.pdf.

- 57.Ready Scotland. 2016. Preparing Scotland: Philosophy, principles, structure and regulatory duties. Accessed February 7, 2017. http://www.readyscotland.org/ready-government/preparing-scotland/.

- 58.Scottish Government. 2013. Building community resilience: Scottish guidance on community resilience. Scottish Government. Last modified April 30, 2013. http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2013/04/2901.

- 59.Ready Scotland. 2017a. Ready Scotland: Preparing for emergencies. Accessed February 7. http://www.readyscotland.org/.

- 60.Ready Scotland. 2017b. NCR. Ready Scotland: Preparing for and dealing with emergencies. Accessed, February 7. http://www.readyscotland.org/ready-government/ncr/.

- 61.UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). 1992. Rio declaration on environment and development. UN Environment. Accessed February 8, 2017. http://www.unep.org/documents.multilingual/default.asp?documentid=78&articleid=1163.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript.