Abstract

Despite aggressive therapies, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is associated with a less than 50% 5-year survival rate. Late stage HNSCC frequently consists of up to 80% cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF). We previously reported that CAF-secreted hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) facilitates HNSCC progression, however very little is known about the role of CAFs in HNSCC metabolism. Here we demonstrate that CAF-secreted HGF increases extracellular lactate levels in HNSCC via upregulation of glycolysis. CAF-secreted HGF induced basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) secretion from HNSCC. CAFs were more efficient than HNSCC in using lactate as a carbon source. HNSCC-secreted bFGF increased mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and HGF secretion from CAFs. Combined inhibition of c-Met and FGFR significantly inhibited CAF-induced HNSCC growth in vitro and in vivo (p<0.001). Our cumulative findings underscore reciprocal signaling between CAF and HNSCC involving bFGF and HGF. This contributes to metabolic symbiosis and a targetable therapeutic axis involving c-Met and FGFR.

Keywords: HNSCC, cancer-associated fibroblast, HGF, bFGF, c-Met, FGFR, glycolysis, glycolytic capacity, OXPHOS, maximal respiration

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the fifth most common cancer globally and represents more than 90% of all head and neck cancers. Despite current scientific and therapeutic advancements, there has been no significant improvement in HNSCC patient survival over the past four decades (1). Conventional treatment options, including surgical resection with radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, are associated with a low 5-year survival. Treatment failure with tumor recurrence is common among patients with HNSCC (2). The poor therapeutic responses underscore the need for an improved understanding of the tumor biology.

Over the last few decades, there has been growing interest in the tumor microenvironment and its role in tumor progression and response to therapy. In addition to cancer cells, a tumor comprises many stromal components, which include tumor infiltrating immune cells, endothelial cells, neuronal cells, lymphatic cells, cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and the extracellular matrix (ECM) (3). In HNSCC, the surrounding stroma contains an abundance of CAFs. Previous studies have reported that CAFs secrete hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (4,5). Further, CAF-secreted HGF binds and activates c-Met tyrosine kinase receptor on HNSCC cells triggering proliferation, invasion and migration (5). HNSCC likely modulates the microenvironment CAFs by secreting basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). Several cancer types secreted bFGF, including HNSCC (6). Secreted bFGF binds to fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) expressed on the cell surface of several cell types and regulates proliferation and migration (7). FGFR inhibition reduces HNSCC growth stimulated by human foreskin fibroblasts (8). Although the autocrine regulation of bFGF is documented, little is known about the paracrine regulation of bFGF between HNSCC and CAFs. Further, the role of CAFs in HNSCC metabolism has not been elucidated.

Unlike normal cells, malignant cells often display increased glycolysis, even in the presence of oxygen; a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect. The metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells leads to the extensive use of glucose for their growth and survival (9). Cells use two major pathways to produce ATP: glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). The glycolytic pathway involves a series of reactions that converts glucose to pyruvate, resulting in ATP, NADH and hydrogen ions. Pyruvate can have three fates: conversion to lactate, conversion of Acetyl-CoA, or conversion to alanine (10). In the conversion of pyruvate to lactate, NADH and hydrogen ions are consumed by LDH5. Lactate and hydrogen ions are pumped out of the cell by several mechanisms to maintain homeostasis of the intracellular pH. The release of protons out of the cell results in extracellular acidifiation. Pyruvate is also converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase to enter the mitochondria and undergo OXPHOS. In many non-transformed differentiated cells such as neurons and fibroblasts, OXPHOS produces most of the cellular ATP. In contrast, cancer cells heavily depend on glycolysis for ATP production. This is supported by the fact that HNSCC has increased lactate levels, which correlates with reduced survival (11). The mechanisms whereby HNSCC tumors survive highly acidic conditions remain unknown; yet, elucidation would provide potential therapeutic targets. In addition, comprehensive studies elucidating cross talk between HNSCC and the surrounding CAFs are lacking. We hypothesized that CAF-secreted HGF regulates HNSCC metabolism and HNSCC-secreted bFGF and lactate regulate CAF proliferation and mitochondrial OXPHOS. Our data elucidate dynamic reciprocal signaling between HNSCC and CAFs. Finally, building on this mechanistic insight we demonstrate the efficacy of simultaneous inhibition of c-Met and FGFR as a therapeutic approach for HNSCC.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Patient samples were collected under the auspices of the Biospecimen Repository Core at the the University of Kansas Cancer Center with written informed consent from patients, using protocols approved by the Human Subjects Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center, in accordance with the U.S. Common Rule (45 CFR 46). Cancer associated fibroblasts were isolated from HNSCC patient samples by dissecting sample into <2 mm components, and allowing the sample to adhere to 10 cm culture dish. CAFs are characterized by their expression of α-smooth muscle actin, and lack of expression of cytokeratin-14, as we demonstrate in our previous publication (5). CAFs were cultured for less than 12 passages to ensure biologic similarity to the original specimen. Well characterized HNSCC cell lines UM-SCC-1, HN5 and OSC-19, (gifts from Dr. Thomas E Carey, University of Michigan; Dr. Jeffrey N Myers, MD Anderson; and Dr. Jennifer R Grandis, University of Pittsburgh, respectfully, obtained in 2013–2014) all authenticated in 2017 by STR profiling (University of Arizona Genetics Core, Tucson, AZ), and confirmed to be negative of mycoplasma using PCR Mycoplasma Test Kit (MD Bioscience, Oakdale, MN), were used in this study (12). HNSCC cells and primary CAF lines were cultured and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS in a humidified 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. In all experiments, results obtained from primary patient lines were confirmed using at least two different patient samples. Conditioned media was collected from a 95% confluent flask of either cancer cells or fibroblasts for a period of 24 h for cancer cells and 72 h for fibroblasts with serum free DMEM.

Reagents

Growth factors, basic fibroblast growth factor (#F0291) and hepatocyte growth factor (#H5791), obtained through Sigma Aldirch, (St. Louis, MO). PF-02341066 (Crizotinib) obtained from Active Biochem (Maplewood, NJ), and AZD-4547 obtained from Chemietek (Indianapolis, IN).

Primary antibodies used: HKII (#2867), phospho p44/42 MAPK (#4370), bFGF (#3196), TFAM (#8076) obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA); MCT1 (NBP1-59656) was obtained from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO); FGFR1 (E10580), FGFR2 (E10570), FGFR3 (E10230) obtained from Spring Bioscience (Pleaston, CA); FGFR4 obtained from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN). β-tubulin (T0198) obtained from Sigma Aldrich. β-actin (#sc-1616) obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). Secondary anti-rabbit IgG Dylight 680 (#35568), anti-rabbit IgG Dylight 488 (#35553), and anti-mouse IgG Dylight 800 (#35521) from ThermoFisher (Waltham, MA).

Primer sequences used: bFGF (F: CTGTACTGCAAAAACGGG; R: AAAGTATAGCTTTCTGCC), c-MET (F: CATGCCGACAAGTGCAGTA; R: TCTTGCCATCATTGTCCAAC), HGF (F: ATCAGACACCACACCGGCACAAAT; R: GAAATAGGGCAATAATCCCAAGGAA), HKII (F: CAAAGTGACAGTGGGTGTGG; R: GCCAGGTCCTTCACTGTCTC), PFK-1 (GGCTACTGTGGCTACCTGGC; R: GCATGGAGTACAGGGAAACC), PGC-1α (F: CCGCACGCACCGAAATTCTC; R: GCCTTCTGCCTGTGCCTCTC); TIGAR (F: CGGAATTCAGAACAGTTTTCCCAAGGATCTCC; R: CGGAATTCAACCTTAGCGAGTTTCAGTCAGTCC); (F: β-ACTIN (F: AGGGGCCGGACTCGTCATACT; R: GGCGGCACCACCATGTACCCT) all obtained from ThermoFisher.

Measurement of Glycolysis and OXPHOS in HNSCC and CAFs

Extracellular acidification and oxygen consumption rates (ECAR and OCR, respectively) were measured using the XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA). To assess effects of conditioned media or growth factors, cells were cultured in serum free media for 24 h, and then exposed to conditioned media or growth factor, with and without inhibitors if applicable, for 48 h. Cells were washed with unbuffered DMEM and equilibrated with 700 μl of pre-warmed unbuffered DMEM containing 1 mM sodium pyruvate at 37 °C for 30 min.Seahorse reagent concentrations: Oligomycin, 1 μM (Sigma, O4876); 2-Deoxyglucose, 100 mM (Sigma, D6134); Glucose, 910 μM (Sigma, G5400); Rotenone, 1μM (Sigma, R8875); FCCP, 0.3 μM (Sigma, C2920); All flux analyses were normalized to protein content (assessed by Bradford assay) within individual wells.

Immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysates were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer with a mixture of protease and phosphatase inhibitors (minitab, Fisher Scientific) on ice. Equal amount of proteins were separated through a 10% SDS-PAGE. Blots were blocked with Odyssey blocking buffer, incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C, and dylight conjugated secondary antibody for 1–2 h. Protein bands were detected using the LI-COR odyssey protein imaging system. Immunoblots for data presented, were analyzed from at least 3 experimental repeats. Densitometric analyses were performed with ImageJ (v1.50i).

Immunofluorescence

HNSCC and CAFs plated in 8 well chamber slides (10,000 cells per well; in combination group, 5,000 cells of each cell type were plated to maintain consistent cell number) under serum-free conditions for 48 h. Methanol (70%) used to fix cells, and subsequently, cells were treated with permeabilization buffer (Triton-X (0.5%) in PBS). 2 % Bovine Serum Albumin in PBS solution used to block cells. Cells were incubated in primary antibody overnight (1:100 concentration at 4 °C). Dylight conjugated antibody used to detect primary. Slides were mounted with a coverslip in vectashield mounting media, and images captured on Nikon Eclipse TE2000 inverted microscope with a photometrics coolsnap HQ2 camera. Fluorescence intensity was quantified using Metamorph software v. 7.8.0.0.

RNA Analysis

RNA was extracted from harvested cells using TRIzol reagent (Fisher) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was subjected to DNAse digestion prior to cDNA preparation using the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). PCR products were resolved on agarose gel and imaged. Agarose gel images of RT-PCR data presented, were analyzed from atleast 3 experimental repeats. Densitometric analyses were performed with ImageJ (v1.50i).

Proliferation and Migration Assays

To assess CAF proliferation, 2 × 103 cells were plated in a 96-well plate in 10% FBS containing DMEM. The media was then replaced with serum-free DMEM, HNSCC conditioned media or recombinant bFGF, with or without inhibitors (AZD-4547 or rotenone) for 72 h. Nuclear content across treatment groups was assessed using the CyQUANT assay kit (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Fold-change in CAF proliferation relative to the vehicle control was determined.

To determine if dual inhibition of c-Met and FGFR mitigate CAF-induced HNSCC proliferation in admixed cultures (2 × 104 cells of each cell type per 6-well plate well), UM-SCC-1 cells were stained with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) per the manufacturer instructions, and extensively washed to remove unbound dye. Cells were treated in duplicate with vehicle control (DMSO), AZD-4547 (2 μM), PF-02341066 (1 μM) or a combination of both inhibitors in serum-free DMEM. After 72 h, cells were trypsinized, washed, fixed in 70% ethanol and suspended in 100 μl of PBS. CFSE-stained UM-SCC-1 cells were analyzed by flow cytometry at 488 nm. Data are presented as fold change in cell number relative to the vehicle control.

To assess the effect of UM-SCC-1 on CAFs migration, CAF cells were seeded in duplicate trans-well inserts (2 × 104 cells per insert) with a pore size of 8 μm (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL) in serum-free media. The inserts were placed in the holding-well containing vehicle control (DMSO), UM-SCC-1-CM with or without AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L) for 24 h. The number of cells that migrated through transwell chamber was counted in 4 fields after hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining using the Hema3 kit (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) by a blinded observer. Cells were plated in parallel along with the corresponding treatment in 96-well plates to assess cell viability using the CyQuant kit (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). The number of cells that migrated through the insert was normalized to the cell viability. Fold-change in CAFs migration in treatment arms relative to the vehicle control was determined.

For single carbon source assessment, Biolog phenotype microarray (Biolog, Hayward, CA) was used following manufacturer’s instructions. A question was raised of glutamine and palmitate alone, and these were not included on the biolog plate. To assess these, we plated cells (1 × 104 cells/well) in HBSS with either glucose (Fisher Scientific) alone, glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich) alone, or palmitate (Sigma-Aldrich) conjugated to Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA, Fisher Scientifc) to dissolve palmitate (BSA as a control was also applied in glucose and glutamine groups) and assessed proliferation over same time period (72 h). Results were normalized to glucose.

siRNA

Cells were transfected with either pooled c-Met siRNA (100 nM) (#sc-29397, pooled of three transcripts, Santa Cruz Biotech. Inc., Dallas, TX) or control siRNA (100 nM) (Santa Cruz proprietary control sequence based upon (13), Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc.) using Lipofectamine-2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 4 h.

Lactate Assessment

Lactate concentration in conditioned media assessed using L-lactate assay kit (Eton Bioscience, San Diego, CA), per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were plated (3 × 105 cells/dish in 60 mm dish) in various conditions for 48 h following 24 h serum starvation.

ELISA

Human HGF (#RAB0212) and bFGF (#RAB0182) ELISA kits were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Cytokine levels were assessed in duplicate wells, per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were plated (3 × 105 cells/dish in 60 mm dish) in various conditions for 48 h following 24 h serum starvation

In vivo Studies

All in vivo protocols were approved by the KUMC Instituional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). To assess the in vivo efficacy of targeting c-Met and FGFR, 100 μl of admixed HNSCC (UM-SCC-1, 1×106 cells) and CAFs (0.5×106 cells) in serum-free DMEM were innoculated into the right flank of athymic nude-Foxn1nu mice. Mice were treated with vehicle control (saline with 1% tween-80), AZD-4547 (15 mg/kg/d), PF-02341066 (15 mg/kg/d) or a combination of AZD-4547 and PF-02341066 via oral gavage, QD five days/week for two weeks. Tumors diameters were measured in two perpendicular dimensions using a vernier caliper, and the volume calculated as previously described (14), briefly (tumor volume = long dimension × short dimension2 × 0.52).

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). For in vitro experiments, data were analyzed using Mann Whitney test for comparison between two groups and Kruskal Wallis test for comparison of multiple groups. For in vivo study, one-way analysis of variance test was employed to assess the level of significance in tumor volumes between treatment arms. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 Version 6.03 (La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was claimed at 95% confidence level (p-value<0.05).

Results

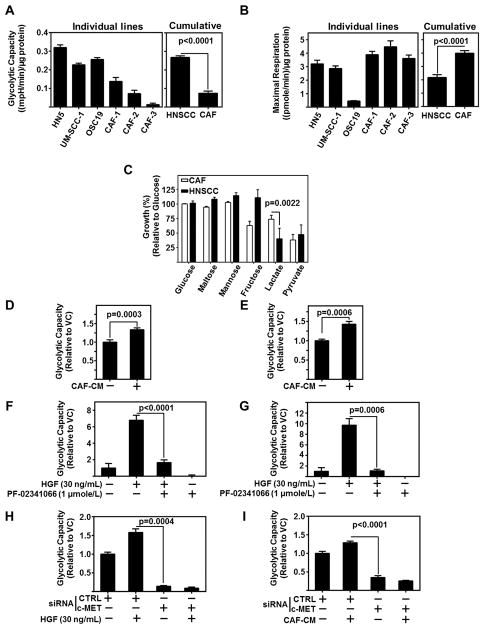

HNSCC Demonstrate Higher Glycolytic Potential than CAFs

Previously, we reported CAF-conditioned media (CM) regulates HNSCC proliferation, migration, and invasion (5). HNSCC tumors are highly glycolytic and increased glycolysis is associated with tumor progression and metastasis. To elucidate the metabolic preferences of HNSCC and CAFs, we assessed the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and the oxygen consumption rate (OCR), to determine glycolytic capacity (Figure 1A) and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (Figure 1B). Compared to CAFs, HNSCC cells demonstrated a significantly higher glycolytic capacity than CAFs (p<0.0001). In contrast, the maximal respiration of CAFs was significantly higher than HNSCC (p<0.0001). To further characterize preferential carbon sources for energy by HNSCC and CAFs, we tested cell proliferation in the presence of a single carbon source. CAFs demonstrate significantly greater growth (p=0.0022) in the presence of lactate as a sole carbon source compared to HNSCC (Figure 1C). An additional finding was that HNSCC utilize fructose more efficiently than CAFs, which may be a consequence of the increased glycolysis in HNSCC, however this finding was not followed in this study. As palmitate and glutamine alone were not included in the Biolog assay plate, we also tested the growth of HNSCC and CAFs exposed to these carbon sources in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and observed no significant differences between HNSCC and CAFs in growth rates to palmitate or glutamine alone (Figure S1A). This single carbon source assay suggests CAFs use lactate more efficiently than HNSCC cells.

Figure 1. CAFs regulate HNSCC Glycolysis through c-Met.

(A) Glycolytic capacity of HNSCC (HN5, UM-SCC-1, OSC19) and three patient derived CAF lines assessed by Seahorse flux analyzer. Graph represents cumulative results from three independent experiments. Combined graph represents mean of all three HNSCC lines and all three CAF lines.

(B) Maximal Respiration of HNSCC (HN5, UM-SCC-1, OSC19) and three patient derived CAF lines assessed by Seahorse flux analyzer. Graph represents cumulative results from three independent experiments. Combined graph represents mean of all three HNSCC lines and all three CAF lines.

(C) Differential growth of CAFs v HNSCC in single carbon sources over 72 h. Data represent cumulative results from four CAF lines and three HNSCC Cell lines.

(D) Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity of HN5 exposed to two CAF-CMs.

(E) Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity of UM-SCC-1 exposed to two CAF-CMs. All error bars in figure represent ± SEM.

(F) HN5 treated with recombinant HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or c-MET inhibitor, PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). ECAR normalized to protein content per well. Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity graphed across treatment arms.

(G) UM-SCC-1 treated with recombinant HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or c-MET inhibitor, PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). ECAR normalized to protein content per well. Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity graphed across treatment arms.

(H) UM-SCC-1 treated with recombinant HGF (30 ng/mL) and either control siRNA (CTRL) or c-MET siRNA. ECAR normalized to protein content per well. Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity graphed across treatment arms.

(I) UM-SCC-1 treated with CAF-CM and and either control siRNA (CTRL) or c-MET siRNA. ECAR normalized to protein content per well. Cumulative results of glycolytic capacity graphed across treatment arms.

CAF-secreted HGF Regulates HNSCC Glycolysis through c-Met

We previously reported that paracrine activation c-Met by CAF-secreted HGF is a contributing event to HNSCC progression (4,5). Additionally, c-Met has been linked to glycolysis as c-Met inhibition reduces intracellular NADPH in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines by downregulating TP53-Induced Glycolysis and Apoptosis Regulator (TIGAR) (15). NADPH is generated when glucose 6-phosphate is oxidized to ribose 5-phosphate in the pentose phosphate pathway, and through the malic enzyme conversion of malate to pyruvate (16). Importantly, NADPH production correlates with glucose uptake (17). These studies led us to question the role of CAF secreted HGF in regulating HNSCC glycolysis. Of note, HGF is secreted in the microenvironment by CAFs not HNSCC, and is readily detectable in CAF-CM (Figure S1B)(4). We found CAF-CM to significantly increase the glycolytic capacity of HNSCC (HN5 (p=0.0003) and UM-SCC-1 (p=0.0006)) (Figure 1D–E).

In order to further elucidate the role of HGF in inducing HNSCC glycolysis, HNSCC cells were stimulated with recombinant HGF, with or without c-Met inhibition using PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). HGF-induced HNSCC glycolysis was inhibited in the presence of PF-02341066 (Figure 1F–G). Inhibition of HGF-induced ECAR and glycolytic capacity by PF-02341066 demonstrates that glycolysis in HNSCC is regulated by c-Met. To confirm the increased ECAR was a result of glycolysis and not by some other biological pathway (58, 59), we directly assessed lactate after HGF stimulation of HNSCC cells. We observed HGF to enhance lactate production (Figure S1C). In order to rule out off-target effects of PF-02341066, HNSCC cells were transfected with c-Met siRNA. c-Met knockdown significantly reduced the ability of HGF (p=0.0004) and CAF-CM (P<0.0001) to increase the glycolytic capacity of HNSCC cells (Figure 1H–I). Met is activated through both ligand, HGF, and ligand-independent means, such as with IGF-1 or EGFRvIII (18,19). PF-02341066 inhbition of c-Met even without HGF applied demonstrates a pronounced decrease in glycolytic capacity, (Figure 1F–G). C-MET silencing with siRNA also demonstrates a decrease in glycolytic capacity (Figure 1H–I), alongside a decrease in HKII and PFK-1, regardless of HGF stimulation (Figure S1D). As HGF is not secreted by HNSCC, these data support a role for ligand independent activation of Met in HNSCC glycolysis. Addition of HGF as a ligand further promotes glycolysis.

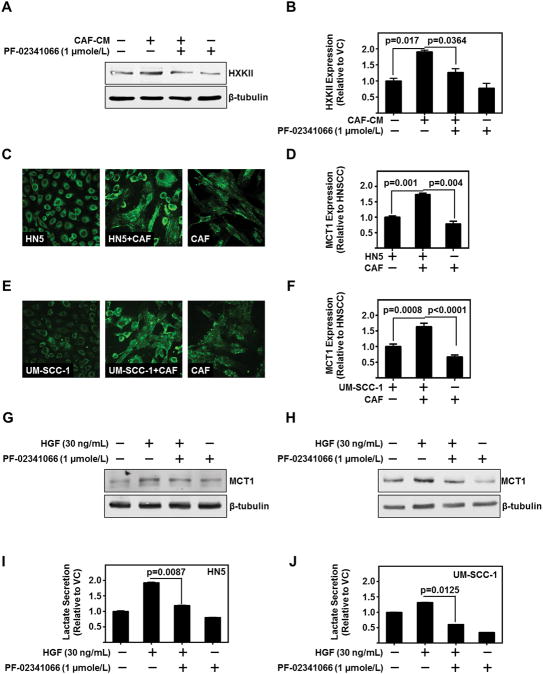

c-Met Regulates HNSCC Glycolysis through Hexokinase-II

Hexokinase-II and phosphofructokinase are key rate limiting enzymes in the glycolytic cascade. Hexokinase-II is highly upregulated in the early stage of tumorigenesis in several cancers including HNSCC (20). Hexokinase-II levels in HNSCC were induced by CAF-CM (p=0.0117) (Figure 2A–B and S2A). Further, c-Met inhibition by PF-02341066 mitigated CAF-CM-induced hexokinase-II levels (p=0.0364) (Figure 2A–B). Knockdown of c-Met with siRNA mitigated CAF-CM or HGF induced hexokinase-II and phosphofructokinase mRNA levels in HNSCC. These results suggest CAF secreted HGF induces key enzymes in the glycolytic pathway of HNSCC.

Figure 2. CAF-Secreted HGF Regulates HNSCC Glycolytic Enzymes and Lactate Production.

(A,B) Representative immunoblot of hexokinase-II (HK-II) protein levels of HN5 treated with CAF-CM and/or c-MET inhibitor, PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). β-tubulin serves as loading control. Cumulative densitometric analysis of HKII/β-tubulin normalized to vehicle control treated lane.

(C,D) Representative immunofluorescent image (Magnificaiton is 200X) of MCT1 (green) on HN5, CAF, or co-culture of HN5 and CAF. Number of cells kept constant between wells. MCT1 levels were assessed as total fluorescent intensity, and cumulative results.

(E,F) Representative immunofluorescent image (Magnificaiton is 200X) of MCT1 (green) on UM-SCC-1, CAF, or co-culture of HN5 and CAF. Number of cells kept constant between wells. MCT1 levels were assessed as total fluorescent intensity, and cumulative results.

(G) Representative immunoblot of MCT1 protein levels expressed in HN5 with treatment of recombinant HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). β-tubulin serves as loading control.

(H) Representative immunoblot of MCT1 protein levels expressed in UM-SCC-1 with treatment of recombinant HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). β-tubulin serves as loading control.

(I) Lactate secretion as assessed by enzymatic based absorbance assay of HN5 treated with HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). Data represent cumulative normalized to vehicle control treated cells.

(J) Lactate secretion as assessed by enzymatic based absorbance assay of HN5 treated with HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). Data represent cumulative results normalized to vehicle control treated cells. Error bars on all graphs represent ± SEM.

Excessive glycolysis is associated with over expression of the lactate transporter MCT1, which is the best characterized transporter of the MCT family (21). MCT1 is overexpressed in HNSCC (11). We hypothesized CAFs enhance MCT1 levels in HNSCC, facilitating lactate secretion from HNSCC. We observed a significant increase in MCT1 levels in co-cultured HNSCC and CAFs as assessed by total fluorescent intensity of the co-culture (HN5 (p=0.0010) and UM-SCC-1 (p=0.0008)) (Figure 2C–F). Additionally, CAF-CM increased MCT1 protein levels in HNSCC (Figure S2A). To evaluate the role of c-Met in regulating MCT1 levels, we stimulated HNSCC with HGF and with c-Met inhibitor PF-02341066. Treatment with PF-02341066 mitigated HGF-mediated induction of MCT1 levels in HNSCC (Figure 2G–H). Further, PF-02341066 treatment decreased HGF-induced lactate secretion from HNSCC (HN5 (p=0.0087) and UM-SCC-1 (p=0.0125)) (Figure 2I–J). Additionally, CAF-CM increased HNSCC lactate secretion, and knockdown of MCT1 mitigated this secretion (Figure S2B). These data demonstrate that CAFs regulate HNSCC glycolysis by HGF induction of key glycolytic enzymes and lactate efflux through MCT1.

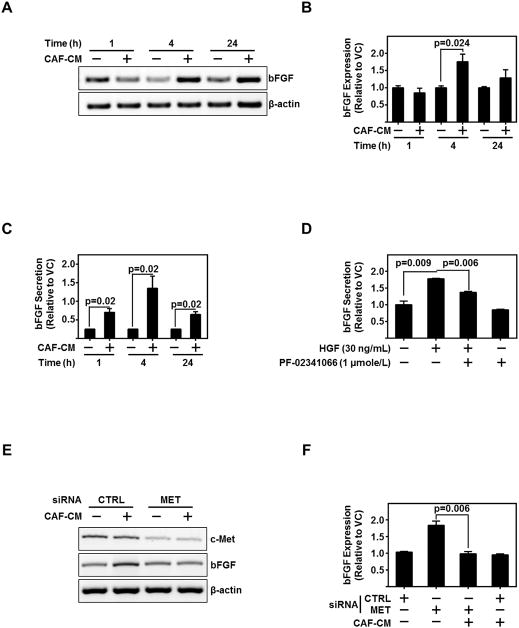

CAF-secreted HGF Regulates bFGF Secretion from HNSCC

FGFRs are expressed in myofibroblasts from both normal oral mucosa and HNSCC (22). However, aberrant FGFR signaling plays an important role in the tumor progression (23). A previous report demonstrated bFGF is essential for autocrine and paracrine activation of FGFR (24). We demonstrate the expression of bFGF in HNSCC cell lines and secretion of bFGF in HNSCC-CM (Figure S3A–B); further, we observe strong expression of FGFR throughout patient-derived CAFs (Figure S3C).

We questioned the interplay of CAF-secreted HGF in stimulating bFGF from HNSCC. CAF-CM induced bFGF mRNA expression and protein secretion (Figures 3A–C). Inhibition of c-Met by either PF-02341066 or siRNA significantly reduced HGF-induced or CAF-CM-induced bFGF secretion from HNSCC (P=0.006) (Figures 3D–F, and S3D). Taken together, these data demonstrate CAF-secreted HGF regulates bFGF expression and secretion in HNSCC through c-Met.

Figure 3. c-Met Regulates bFGF Expression in HNSCC.

(A,B) Representative PCR product of bFGF mRNA in UM-SCC-1 treated with CAF-CM for the indicated time points. β-actin serves as loading control. Graph depicts cumulative densitometric results of three independent experiments of bFGF/β-actin normalized to vehicle control treated cells at each timepoint.

(C) Graph depicts ELISA protein assessment of bFGF secreted from HN5 exposed to three different CAF-CMs. Cumulative data from three independent experiments are normalized to vehicle treated cells at each timepoint.

(D) Graph depicts ELISA protein assessment of bFGF secreted from UM-SCC-1 exposed to either HGF (30 ng/mL) and/or c-MET inhibitor, PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L). Cumulative data from three independent experiments are normalized to vehicle treated cells.

(E,F) representative PCR product of c-MET, bFGF, or β-actin (as loading control) mRNA in UM-SCC-1 exposed to CAF-CM with either control siRNA (CTRL) or c-Met siRNA. Cumulative results from three independent experiments of bFGF/β-actin normalized to CTRL siRNA, vehicle treated UM-SCC-1. Error bars on all graphs representative ± SEM.

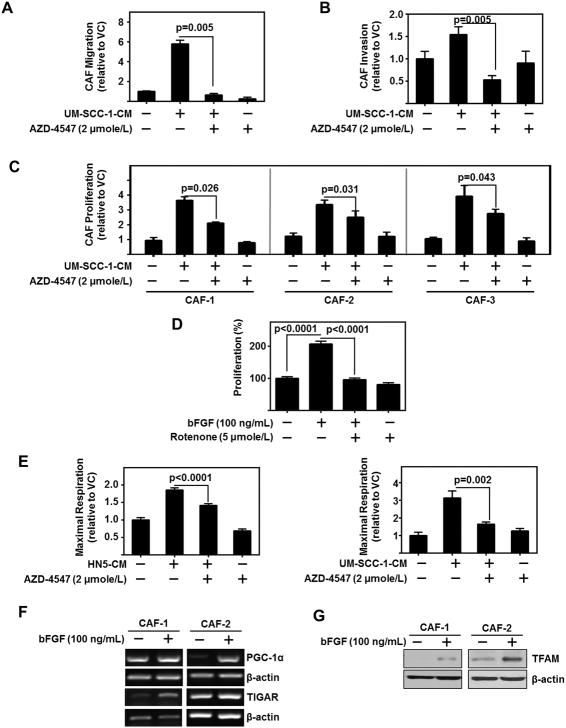

HNSCC-secreted bFGF Stimulates OXPHOS, Proliferation and Migration in CAFs

Under physiological conditions, normal cells use OXPHOS to produce cellular energy. In contrast, cancer cells rely heavily on glycolysis to produce energy and promote tumor progression. Recent studies demonstrate metabolic reprograming in CAFs promotes tumor progression (25). For example, highly glycolytic lung tumors reprogram their stromal cells to survive even in low glucose conditions (26). Recently, FGFR was shown to activate mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-1 (PDK1) and regulate the metabolic activity of cancer cells (27). Based upon this, we hypothesized HNSCC-secreted bFGF mediates and alters CAF metabolism. In support of this, we observed HNSCC-CM to increase CAF migration, invasion and proliferation in an FGFR-dependent manner (Figure 4A–C). In order to determine if mitochondrial OXPHOS was necessary for CAF proliferation, we treated CAFs with increasing doses of rotenone, a mitochondrial complex I inhibitor to determine the IC50 value. We then used half the IC50 to inhibit mitochondrial OXPHOS without inducing cell cytotoxicity over 72 h. Our data demonstrate that rotenone treatment significantly attenuated bFGF induction of CAF proliferation (p<0.0001) (Figure 4D). This indicates the regulation of OXPHOS in CAFs is necessary to obtain the proliferation phenotype. We assessed OXPHOS in CAFs treated with HNSCC-CM with or without pan-FGFR inhibitor, AZD-4547. HNSCC-CM increases maximal respiration in CAFs, which is mitigated by AZD-4547 (HN5-CM (p<0.0001) and UM-SCC-1 (p=0.0002)) (Figure 4E). These results suggest HNSCC-secreted bFGF plays an important role in the regulation of OXPHOS in CAFs.

Figure 4. HNSCC regulates CAFs through bFGF induction of OXPHOS.

(A) HNSCC-CM (UM-SCC-1) enhanced CAF migration is attenuated by AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L). Migration assessed using transwell assay. Data represent cumulative results from three independent experiments and are normalized to cell viability.

(B) HNSCC-CM (UM-SCC-1) enhanced CAF invasion is attenuated by AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L). Invasion assessed using transwell assay. Data represent cumulative results from three independent experiments and are normalized to cell viability. Error bars on all graphs represent ± SEM.

(C) HNSCC-CM enhanced CAF proliferation is attenuated by AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L). Three CAF lines were treated with UM-SCC-1-CM and/or AZD-4547. Graphs depict three independent experiments for each cell line.

(D) HNSCC-induced CAF proliferation is dependent on OXPHOS. Proliferation of CAFs in presence of bFGF (100 ng/mL) and/or Rotenone (5 μmole/L). Graph depicts cumulative results of three experiments plated in triplicate, error bars represent ± SEM.

(E) CAF were treated with HN5-CM or UM-SCC-1-CM and/or FGFR inhibitor, AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L). Data normalized to protein content per well. Graph depicts fold change in maximum respiration normalized to basal media control cells.

(F) Representative PCR product of PGC-1α and TIGAR from two patient-derived CAF lines treated with bFGF (100 ng/mL); β-actin serves as loading control.

(G) Representative immunoblot of TFAM from two patient-derived CAF lines treated with bFGF (100 ng/mL). β-actin serves as loading control.

Expression of p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis (TIGAR) promotes mitochondrial OXPHOS in breast carcinoma cells through the utilization of lactate and glutamate (28). In addition, TIGAR hydrolyses fructose-2,6-bisphosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate decreasing their levels and consequently reducing glycolysis (15). We tested the effect of bFGF on TIGAR mRNA levels in two patient-derived CAF lines. Our data demonstrate that bFGF induced the expression of TIGAR in both CAF lines (Figure 4F). Additionally, FGF signaling has previously been associated with activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) (29). PGC-1α is a well-known regulator of mitochondrial OXPHOS (30–32). In CAFs, bFGF induced PGC-1α expression (Figure 4F). PGC-1α enhances the transcription of transcription factor A, mitochondrial (TFAM), an important transcription factor in mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS (31,32). bFGF induces the expression of TFAM in CAFs (Figure 4G). These data indicate that bFGF attenuates CAF glycolysis through increased transcription of TIGAR, and stimulates CAF OXPHOS by inducing expression of PGC-1α and TFAM.

These results demonstrate HNSCC-secreted bFGF regulates CAF OXPHOS, proliferation, migration, and invasion. Moreover, FGFR inhibition did not return CAF proliferation and migration to baseline levels, indicating a role for other HNSCC-secreted factors. Nonetheless, these data support HNSCC-secreted bFGF as a key factor responsible for induction of CAF mitochondrial OXPHOS, proliferation and migration. This finding is particularly important as invasive CAFs may lead the metastatic cascade (33).

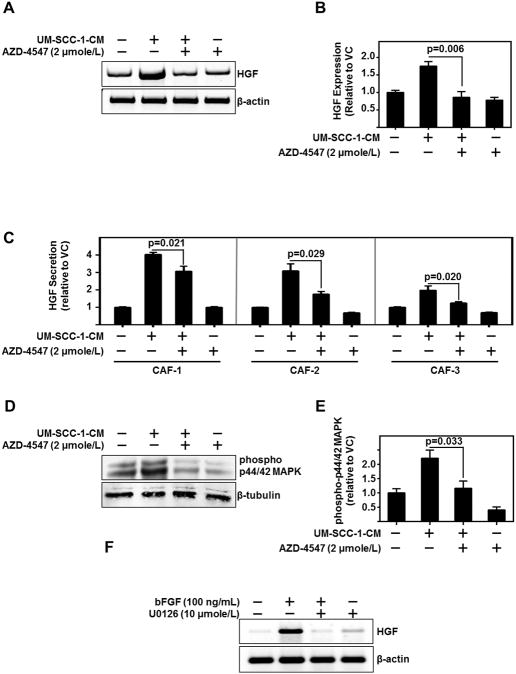

HNSCC-secreted bFGF Regulates HGF Secretion from CAFs

Since HNSCC induces CAF HGF secretion (5), we assessed whether CAF-secreted HGF was a consequence of HNSCC-secreted-bFGF. We demonstrate FGFR inhibition significantly reduces HNSCC-CM-induced HGF expression and secretion from CAFs (CAF-1 (p=0.021), CAF-2 (p=0.029) and CAF-3 (p=0.020)) (Figure 5A–C). With this observation, we wanted to further delineate the mechanism of bFGF regulating HGF. Activation of FGFR triggers phosphorylation and signaling through p44/42 MAPK. We found HNSCC-CM significantly induced phosphorylation of p44/42 MAPK in CAFs which was attenuated by FGFR inhibition (p=0.033) (Figure 5D–E). Moreover, p44/42 MAPK inhibition with U0126 decreased HGF expression in CAFs (Figure 5F). Taken together these results suggest that HNSCC-secreted bFGF induces p44/42 MAPK phosphorylation, which in turn regulates HGF production in CAFs.

Figure 5. HNSCC Cells Regulate HGF Levels in CAFs via FGFR and MAPK.

(A,B) Representative PCR product of HGF and β-actin (used as loading control) in CAF treated with UM-SCC-1-CM and/or FGFR inhibitor, AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L). Graph depicts cumulative results of three independent experiments.

(C) ELISA protein assessment of HGF secreted from 3 CAF lines treated with UM-SCC-1-CM and/or AZD4547 (2 μmole/L). Graph depicts cumulative results form three independent experiments normalized to vehicle control treated CAF.

(D,E) Representative immunoblot of phospho- p44/42 MAPK and β-tubulin (used as loading control) in CAF treated with UM-SCC-1-CM and/or AZD4547 (2 μmole/L). Graph depicts cumulative results form three independent experiments of phospho p44/42 MAPK/β-tubulin normalized to vehicle control treated CAF.

(F) Representative PCR product of HGF and β-actin (used as loading control) of CAF treated with either bFGF (100 ng/mL) and/or p44/42 MAPK inhibitor, U0126 (10 μmole/L).

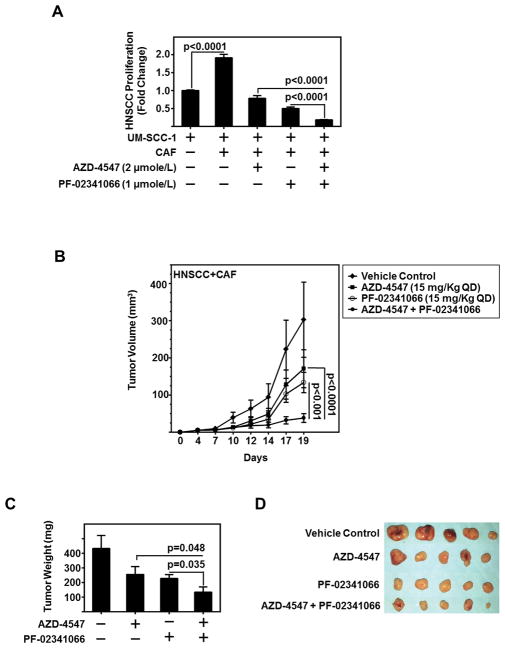

Combined Inhibition of c-Met and FGFR Inhibits CAF-facilitated HNSCC Proliferation In vitro and Xenograft Growth In vivo

With this recipricoal symbiosis, we sought to determine the effect of combinatorial c-Met and FGFR inhibiton in HNSCC-CAF models. HNSCC rapidly proliferates in the presence of CAFs, with a two-fold increase observed (Figure 6A). Using combined treatment with c-Met inhibitor PF-02341066 and FGFR inhibitor AZD-4547, HNSCC proliferation induced by CAFs was significantly decreased compared with either single agent alone (p<0.001) (Figure 6A). In co-cultured cells, the reciprocal activation of c-Met on HNSCC and FGFR on CAFs further induces signaling, resulting in increased tumor glycolysis and growth. Combined inhibition of both receptors in admixed cultures interferes with the reciprocal signaling between the two cell types. Thus, the combination treatment group reduced HNSCC proliferation below CAF induced levels. We assessed the combinatorial effect by Bliss analysis, and found the combination of PF-02341066 and AZD-4547 to be additive in nature (Figure S4A). The combined inhibition of both cell populations potentiates the effect of targeting either cell population alone, and demonstrates in vitro the therapeutic relevance of combination therapy in vitro.

Figure 6. Dual Inhibition of c-Met and FGFR Reduces HNSCC Tumor Growth In vitro and In vivo.

(A) CAF-facilitated UM-SCC-1 proliferation attenuated in FGFR inhibitor, AZD-4547 (2 μmole/L), or c-Met inhibitor, PF-02341066 (1 μmole/L), or combination of AZD-4547 and PF-02341066. Graph depicts cumulative results of CFSE-sorted UM-SCC-1 counted by flow cytometry from three independent experiments and normalized to UM-SCC-1 alone with no CAFs.

(B) CAF (0.5 × 106 cells)-HNSCC (1 × 106 cells) admixed tumor inoculated subcutaneously in athymic nude-Foxn1nu mice volume decreases with treatment of AZD-4547 (15 mg/kg QD) and/or PF-02341066 (15 mg/kg QD) (n=5/group).

(C) Graph depicts mean tumor weight of each treatment group from admixed CAF-HNSCC xenograft experiment depicted in (B). Error bars on all graphs represent ± SEM.

(D) gross images of tumors excised from CAF-HNSCC xenograft experiment depicted in (B).

We previously observed CAF and HNSCC xenograft tumors grow at a faster rate than HNSCC alone (5). Thus, we sought to determine the antitumor efficacy of combined inhibition of c-Met and FGFR in an admixed HNSCC-CAF model. HNSCC (UM-SCC-1) cells admixed with CAFs (2:1 ratio) were injected subcutaneously in the flank of athymic nude-Foxn1nu mice. Established tumor-bearing mice were treated orally QD with vehicle control, PF-02341066 (15 mg/kg QD), AZD-4547 (15 mg/kg QD), or combination of PF-02341066 and AZD-4547 (15 mg each/kg QD) for five days a week. Combined treatment with PF-02341066 and AZD-4547 demonstrated significant reduction in tumor volume compared to treatment with either agent alone (p<0.001) (Figure 6B). Moreover, the reduction in tumor weight on combined treatment was significantly decreased compared to either PF-02341066 (P=0.035) or AZD-4547 (P=0.048) treatment alone (Figure 6C–D). No significant differences were observed in HNSCC only xenografts (Figure S4B). Taken together, our data suggest that combined inhibition of FGFR and c-Met has greater antitumor effects than either agent alone.

Discussion

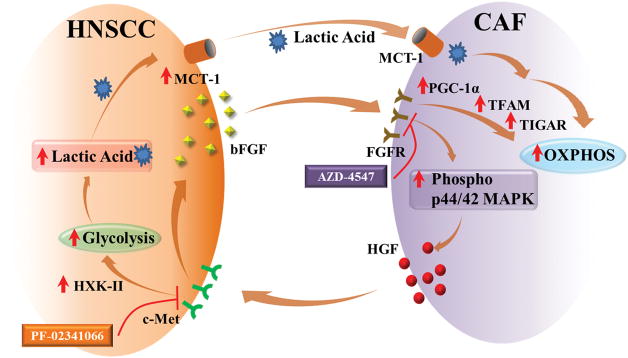

In spite of recent advances in cancer treatment, current therapies for HNSCC are associated with poor survival and high morbidity. Innovative therapeutic strategies are needed for improved treatment of this disease. Despite a long-known recognition that the enhanced proliferation of cancer cells is associated with altered energy metabolism, no therapeutics are clinically available for HNSCC patients which target metabolism. Additionally, the underlying biology explaining a mechanism for dysregulated metabolism is poorly understood. We find in this study that CAFs promote HNSCC glycolysis, and act as a cellular compartment to sequester and use the resultant lactate. This creates a metabolic symbiosis where both cell types feed off each other to enhance proliferation, migration, and progression of this disease (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Schematic Representation of Tumor-Stroma Metabolic Symbiosis.

HNSCC-secreted bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) increases p44/42 MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) phosphorylation which induces secretion of HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) from CAFs which binds to the c-Met receptor on HNSCC cells inducing secretion of bFGF from HNSCC cells. Further, HGF regulates expression of HXK-II (hexokinase-II) and increases cellular glycolysis. Lactic acid produced through glycolysis is transported out of the cells by MCT-1 (monocarboxyl transporter-1). The lactic acid is used by CAFs as a source of energy through OXPHOS. OXPHOS in CAFs is induced by agonization of FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) by bFGF. This induces increased expression of PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α) and TFAM (Transcription Factor A, mitochondria), which increase OXPHOS. Additionally bFGF induces the expression of TIGAR (p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis), which downregulates glycolysis and increases OXPHOS. All in all, CAFs and HNSCC metabolically couple to facilitate tumor progression, and targeting this symbiosis inhibits tumor growth.

A large portion of late stage HNSCC tumors consists of CAFs. An increased ratio of CAFs to HNSCC correlates with increased tumor volume (34). Additonally, migrating HNSCC derived CAFs lead the invasive front in the metastatic process (33). Reciprocal signaling between the tumor and stroma has been reported in several cancers to facilitate tumor growth, invasion and resistance to therapy. Even though great strides have been made in understanding cancer cell metabolism, there exists a large gap in the knowledge pertaining to metabolic symbiosis between the tumor and cells in the microenvironment.

Previously, we reported that CAFs enhance HNSCC growth and metastasis (4,5). Further, we and others reported that c-Met and its ligand HGF are overexpressed in various cancer types including HNSCC (4,35). Although we could not detect HGF secretion from HNSCC cell lines (Figure S2A), we reported that paracrine activation of c-Met by CAF-secreted HGF facilitates HNSCC progression (4). Very little is known about the regulation of HGF in CAFs and its impact on HNSCC metabolism.

HNSCC tumors are highly glycolytic and are routinely diagnosed using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) imaging. 18F-FDG uptake in HNSCC tumors correlates with high lactate levels, poor prognosis and reduced survival (36). In addition to glycolysis, glutaminolysis also produces lactate in cancer cells. However, it has been demonstrated that glucose, not glutamine, is the dominant energy source in a panel of 15 HNSCC cell lines (37).

Lactate produced as a byproduct of glycolysis is actively transported out of the cell by MCT1, a bi-directional lactate transporter that is overexpressed in several tumors (38). MCT1 inhibition decreases lactate efflux, proliferation, cell biomass, migration and invasion in breast cancer cells (39). A high level of stromal MCT1 is a negative prognostic factor in non-small cell lung cancer (40). Our data demonstrate an increase in MCT1 levels in admixed cultures of HNSCC and CAFs. C-Met inhibition reduced MCT1 levels and lactate production in HNSCC cells. This corroborates reports which link MET signaling intermediates MAPK and STAT3 with MCT1(41,42).

Expression of FGFR and its ligands has been reported in various cancers, including HNSCC (43). FGFR plays a pivotal role in tumorigenesis by regulating a multitude of processes, including cell survival, proliferation, metastasis and angiogenesis (44). FGFR has been linked to metabolic alterations as FGFR knockout mice demonstrate altered metabolism, and FGFR1 directly regulates mitochondrial respiration through inducation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) (45,46). Our data demonstrate that bFGF stimulation of CAFs induces expression of PGC-1α and its downstream target transcription factor A, mitochondrial (TFAM). TFAM is a stimulatory component of the transcriptional complex that regulates the expression of all 13 proteins encoded by mitochondrial DNA that function as essential subunits of respiratory complexes I, III, IV and V (47). In addition, we demonstrate increased transcription of p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis (TIGAR) in CAFs. TIGAR hydrolyses fructose-2,6-bisphosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate decreasing their levels and consequently reducing glycolysis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (15). In addition, TIGAR promotes mitochondrial OXPHOS in breast carcinoma cells through the utilization of lactate and glutamate (28). Increased expression of TIGAR, PGC-1α and TFAM on bFGF stimulation in CAFs indicates the mechanism by which CAFs undergo metabolic reprogramming to enhance OXPHOS.

In this present work, we demonstrate that c-Met inactivation alters HNSCC metabolism alongiside a mitigation of CAF-stimulated bFGF protein secretion from HNSCC. Activation of multiple signaling pathways occur downstream of HGF/c-Met. These include p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p44/42 MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt (48). Further, FGFR inhibition reduced both HNSCC and stromal compartments in xenograft models (8). Our data corroborates and extends previous reports demonstrating bFGF-mediated FGFR activation triggers downstream p44/42 MAPK signaling a well known regulator of cell proliferation (49). Indeed, FGFR-mediates proliferation of CAFs on stimulation with HNSCC conditioned media. Inhibition of mitochondrail OXPHOS using half the IC50 dose of rotenone, attenuated bFGF-induced CAF proliferation without significant cytotoxicity. Mitochondrial OXPHOS has been reported to be important for proliferation in other cell types (50,51). In addition to regulating cell proliferation, our data demonstrate that HNSCC cells regulate HGF secretion from CAFs via FGFR. This finding is in agreement with previous reports demonstrating regulation of HGF secretion by bFGF in mesenchymal cells (52), and in murine cells (53). Together these findings support our hypothesis of a dynamic reciprocal interaction between HNSCC and CAFs that facilitates HNSCC tumor metabolism and progression throughc-Met/FGFR signaling as shown in graphical abstract.

Clinically relevant small molecule c-Met inhibitor PF-02341066 (crizotinib), effectively reduces HNSCC growth in vitro and in vivo and circumvents acquired resistance to molecular targeted therapy (54). PF-02341066 is a competitive ATP inhibitor that induces apoptosis, and inhibits cell proliferation, angiogenesis, migration and invasion in multiple pre-clinical cancer models. Further, PF-02341066 potentiates the effects of radiation and chemotherapeutic agents. Here we have shown that c-Met inhibition with PF-02341066 reduced glycolysis and bFGF expression in HNSCC. AZD-4547 is a clinically relevant small molecule pyrazoloamide derivative, pan FGFR tyrosine kinases inhibitor (55). AZD-4547 has been reported to inhibit progression of numerous cancers, and we demonstrate that FGFR inhibition with AZD-4547 reduces OXPHOS, proliferation, migration and HGF expression in CAFs.

Based on our mechanistic insights we tested the antitumor efficacy of FGFR inhibitor AZD-4547 in combination with c-Met inhibitor PF-02341066 both in vitro and in vivo, and show, for the first time, that the combination treatment significantly inhibited HNSCC growth in vitro and in vivo. Our cumulative findings underscore the therapeutic potential of combinatorial treatment with PF-02341066 and AZD-4547 in HNSCC

Supplementary Material

Statement of Significance.

HNSCC cancer cells and CAFs have a metabolic relationship where CAFs secrete HGF to induce a glycolytic switch in HNSCC cells and HNSCC cells secrete bFGF to promote lactate consumption by CAFs.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: American Head and Neck Society Pilot Award (S.M. Thomas), University of Kansas Medical Center and University of Kansas Cancer Center’s CCSG (1-P30-CA168524-02) (S.M. Thomas), Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Institutional Development Award (IDeA), National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH (P20 GM103418) (D. Kumar), The KUMC Biomedical Research Training Program Fellowship (J. New), 5P20RR021940-07 and 8P20GM103549-07 (P. Krishnamurthy), CA190291 (S. Anant), PA CURE award and in part P30CA047904 (B.Van Houten) were the funding sources. We acknowledge support from the University of Kansas Cancer Center, Biospecimen Repository Core Facility.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Matta A, Ralhan R. Overview of current and future biologically based targeted therapies in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck oncology. 2009;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim L, King T, Agulnik M. Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology and public health implications. Oncology. 2010;24(10):915–9. 24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curry JM, Sprandio J, Cognetti D, Luginbuhl A, Bar-ad V, Pribitkin E, et al. Tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Seminars in oncology. 2014;41(2):217–34. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowles LM, Stabile LP, Egloff AM, Rothstein ME, Thomas SM, Gubish CT, et al. HGF and c-Met participate in paracrine tumorigenic pathways in head and neck squamous cell cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2009;15(11):3740–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler S, Shi H, Lin F, Dasari S, Bednash J, Thorne S, et al. Enhancement of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by tumor-associated fibroblasts in preclinical models. Head & neck. 2014;36(3):385–92. doi: 10.1002/hed.23312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riedel F, Gotte K, Bergler W, Rojas W, Hormann K. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor protein and its down-regulation by interferons in head and neck cancer. Head & neck. 2000;22(2):183–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(200003)22:2<183::aid-hed11>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vairaktaris E, Ragos V, Yapijakis C, Derka S, Vassiliou S, Nkenke E, et al. FGFR-2 and −3 play an important role in initial stages of oral oncogenesis. Anticancer research. 2006;26(6b):4217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweeny L, Liu Z, Lancaster W, Hart J, Hartman YE, Rosenthal EL. Inhibition of fibroblasts reduced head and neck cancer growth by targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(7):1539–44. doi: 10.1002/lary.23266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen PL. Warburg, me and hexokinase 2: Multiple discoveries of key molecular events underlying one of cancers’ most common phenotypes, the “Warburg Effect”, i.e. elevated glycolysis in the presence of oxygen. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39(3):211–22. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray LR, Tompkins SC, Taylor EB. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2014;71(14):2577–604. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curry JM, Tuluc M, Whitaker-Menezes D, Ames JA, Anantharaman A, Butera A, et al. Cancer metabolism, stemness and tumor recurrence: MCT1 and MCT4 are functional biomarkers of metabolic symbiosis in head and neck cancer. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2013;12(9):1371–84. doi: 10.4161/cc.24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sano D, Xie T-X, Ow TJ, Zhao M, Pickering CR, Zhou G, et al. Disruptive TP53 Mutation is Associated with Aggressive Disease Characteristics in an Orthotopic Murine Model of Oral Tongue Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17(21):6658–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keeton EK, Brown M. Cell Cycle Progression Stimulated by Tamoxifen-Bound Estrogen Receptor-α and Promoter-Specific Effects in Breast Cancer Cells Deficient in N-CoR and SMRT. Molecular Endocrinology. 2005;19(6):1543–54. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler SE, Shi H, Lin F, Dasari S, Bednash J, Thorne S, et al. Tumor associated fibroblasts enhance head and neck squamous cell carcinoma proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in preclinical models. Head & neck. 2014;36(3):385–92. doi: 10.1002/hed.23312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lui VW, Wong EY, Ho K, Ng PK, Lau CP, Tsui SK, et al. Inhibition of c-Met downregulates TIGAR expression and reduces NADPH production leading to cell death. Oncogene. 2011;30(9):1127–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang P, Du W, Mancuso A, Wellen KE, Yang X. Reciprocal regulation of p53 and malic enzymes modulates metabolism and senescence. Nature. 2013;493(7434):689–93. doi: 10.1038/nature11776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B, Qiu B, Lee DS, Walton ZE, Ochocki JD, Mathew LK, et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase opposes renal carcinoma progression. Nature. 2014;513(7517):251–5. doi: 10.1038/nature13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varkaris A, Gaur S, Parikh NU, Song JH, Dayyani F, Jin J-K, et al. Ligand-independent activation of MET through IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling. International Journal of Cancer. 2013;133(7):1536–46. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Puliyappadamba VT, Chakraborty S, Rehman A, Vemireddy V, Saha D, et al. EGFR wild type antagonizes EGFRvIII-mediated activation of Met in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2015;34(1):129–34. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathupala SP, Ko YH, Pedersen PL. Hexokinase II: Cancer’s double-edged sword acting as both facilitator and gatekeeper of malignancy when bound to mitochondria. Oncogene. 2006;25(34):4777–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy KM, Dewhirst MW. Tumor metabolism of lactate: the influence and therapeutic potential for MCT and CD147 regulation. Future oncology (London, England) 2010;6(1):127–48. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes SE. Differential expression of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) multigene family in normal human adult tissues. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 1997;45(7):1005–19. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellacono FR, Spiro J, Eisma R, Kreutzer D. Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor and its receptors by head and neck squamous carcinoma tumor and vascular endothelial cells. American journal of surgery. 1997;174(5):540–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansukhani A, Bellosta P, Sahni M, Basilico C. Signaling by fibroblast growth factors (FGF) and fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2)-activating mutations blocks mineralization and induces apoptosis in osteoblasts. J Cell Biol. 2000;149(6):1297–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.6.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, Wang Y, Shi Z, Liu J, Sun P, Hou X, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts by IDH3alpha downregulation. Cell Rep. 2015;10(8):1335–48. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaudhri VK, Salzler GG, Dick SA, Buckman MS, Sordella R, Karoly ED, et al. Metabolic alterations in lung cancer-associated fibroblasts correlated with increased glycolytic metabolism of the tumor. Molecular cancer research : MCR. 2013;11(6):579–92. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0437-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hitosugi T, Fan J, Chung TW, Lythgoe K, Wang X, Xie JX, et al. Tyrosine Phosphorylation of Mitochondrial Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1 Is Important for Cancer Metabolism. Molecular Cell. 2011;44(6):864–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ko Y-H, Domingo-Vidal M, Roche M, Lin Z, Whitaker-Menezes D, Seifert E, et al. TIGAR Metabolically Reprograms Carcinoma and Stromal Cells in Breast Cancer. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2016 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.740209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potthoff MJ, Inagaki T, Satapati S, Ding X, He T, Goetz R, et al. FGF21 induces PGC-1alpha and regulates carbohydrate and fatty acid metabolism during the adaptive starvation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(26):10853–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904187106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBleu VS, O’Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis Marcia C, et al. PGC-1α mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nature Cell Biology. 2014;16:992. doi: 10.1038/ncb3039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deblois G, St-Pierre J, Giguere V. The PGC-1/ERR signaling axis in cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32(30):3483–90. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell metabolism. 2005;1(6):361–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaggioli C, Hooper S, Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Grosse R, Marshall JF, Harrington K, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(12):1392–400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bae JY, Kim EK, Yang DH, Zhang X, Park YJ, Lee DY, et al. Reciprocal interaction between carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and squamous carcinoma cells through interleukin-1alpha induces cancer progression. Neoplasia (New York, NY) 2014;16(11):928–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Renzo MF, Poulsom R, Olivero M, Comoglio PM, Lemoine NR. Expression of the Met/hepatocyte growth factor receptor in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer research. 1995;55(5):1129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada T, Uchida M, Kwang-Lee K, Kitamura N, Yoshimura T, Sasabe E, et al. Correlation of metabolism/hypoxia markers and fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Or Surg or Med or Pa. 2012;113(4):464–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandulache VC, Ow TJ, Pickering CR, Frederick MJ, Zhou G, Fokt I, et al. Glucose, Not Glutamine, Is the Dominant Energy Source Required for Proliferation and Survival of Head and Neck Squamous Carcinoma Cells. Cancer. 2011;117(13):2926–38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty JR, Cleveland JL. Targeting lactate metabolism for cancer therapeutics. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123(9):3685–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI69741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morais-Santos F, Granja S, Miranda-Goncalves V, Moreira AH, Queiros S, Vilaca JL, et al. Targeting lactate transport suppresses in vivo breast tumour growth. Oncotarget. 2015;6(22):19177–89. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Bougioukas G, Sivridis E. Lung cancer: a comparative study of metabolism related protein expression in cancer cells and tumor associated stroma. Cancer biology & therapy. 2007;6(9):1476–9. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.9.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhalla S, Evens AM, Dai B, Prachand S, Gordon LI, Gartenhaus RB. The novel anti-MEK small molecule AZD6244 induces BIM-dependent and AKT-independent apoptosis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2011;118(4):1052–61. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-340109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva LS, Goncalves LG, Silva F, Domingues G, Maximo V, Ferreira J, et al. STAT3:FOXM1 and MCT1 drive uterine cervix carcinoma fitness to a lactate-rich microenvironment. Tumor Biology. 2016;37(4):5385–95. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall ME, Hinz TK, Kono SA, Singleton KR, Bichon B, Ware KE, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptors are components of autocrine signaling networks in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17(15):5016–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katoh M, Nakagama H. FGF receptors: cancer biology and therapeutics. Medicinal research reviews. 2014;34(2):280–300. doi: 10.1002/med.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ornitz DM, Itoh N. The Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling pathway. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Developmental Biology. 2015;4(3):215–66. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mäkelä J, Tselykh TV, Maiorana F, Eriksson O, Do HT, Mudò G, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-21 enhances mitochondrial functions and increases the activity of PGC-1α in human dopaminergic neurons via Sirtuin-1. SpringerPlus. 2014;3:2. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scarpulla RC. Nuclear Control of Respiratory Chain Expression by Nuclear Respiratory Factors and PGC-1-Related Coactivator. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1147(1):321–34. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Usatyuk PV, Fu PF, Mohan V, Epshtein Y, Jacobson JR, Gomez-Cambronero J, et al. Role of c-Met/Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3k)/Akt Signaling in Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF)-mediated Lamellipodia Formation, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Generation, and Motility of Lung Endothelial Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289(19):13476–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang H, Xia Y, Lu SQ, Soong TW, Feng ZW. Basic fibroblast growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation of mouse bone marrow stromal cells requires FGFR-1, MAPK/ERK, and transcription factor AP-1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283(9):5287–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinberg F, Hamanaka R, Wheaton WW, Weinberg S, Joseph J, Lopez M, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(19):8788–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen Walter W, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini David M. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell. 2015;162(3):540–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roletto F, Galvani AP, Cristiani C, Valsasina B, Landonio A, Bertolero F. Basic fibroblast growth factor stimulates hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor secretion by human mesenchymal cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 1996;166(1):105–11. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199601)166:1<105::AID-JCP12>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Onimaru M, Yonemitsu Y, Tanii M, Nakagawa K, Masaki I, Okano S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor-2 gene transfer can stimulate hepatocyte growth factor expression irrespective of hypoxia-mediated downregulation in ischemic limbs. Circ Res. 2002;91(10):923–30. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043281.66969.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stabile LP, He G, Lui VW, Thomas S, Henry C, Gubish CT, et al. c-Src activation mediates erlotinib resistance in head and neck cancer by stimulating c-Met. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(2):380–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gavine PR, Mooney L, Kilgour E, Thomas AP, Al-Kadhimi K, Beck S, et al. AZD4547: An Orally Bioavailable, Potent, and Selective Inhibitor of the Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Family. Cancer research. 2012;72(8):2045–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.