Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Inheritance of the ε4 allele of apolipoprotein E (APOE) increases a person’s risk of developing both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Lewy body dementia (LBD), yet the underlying mechanisms behind this risk are incompletely understood. The recent identification of reduced APOE DNA methylation in AD postmortem brain (PMB) prompted this study to investigate APOE methylation in LBD.

METHODS

Genomic DNA from PMB tissues (frontal lobe and cerebellum) of neuropathological pure (np) Controls, npAD, LBD + AD, and npLBD subjects were bisulfite pyrosequenced. DNA methylation levels of two APOE subregions were then compared for these groups.

RESULTS

APOE DNA methylation was significantly reduced in npLBD compared to npControls, and methylation levels were lowest in the LBD + AD group.

DISCUSSION

Given that npLBD and npAD PMB shared a similar reduction in APOE methylation, it is possible that an aberrant epigenetic change in APOE is linked to risk for both diseases.

Keywords: Lewy body dementia (LBD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), DNA methylation, apolipoprotein E (APOE), differentially methylated region (DMR), differential methylation, postmortem brain, human, frontal lobe, cerebellum, pyrosequencing, epigenetics, dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)

1. Introduction

Lewy body dementia (LBD) affects about 1.3 million Americans and their families, making it the most common form of non-Alzheimer’s dementia [1]. Few studies have been conducted on the role of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele in LBD, but following the trajectory of past studies in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), researchers have shown that the inheritance of the ε4 allele increases a person’s risk of developing LBD [2–4] and is associated with an earlier age of death for people diagnosed with LBD [4]. Despite these findings, the precise contributions of APOE ε4 remain unclear in both diseases. As a step toward clarifying the role of APOE ε4, we recently identified an altered epigenetic mark of APOE in the postmortem brains (PMBs) of subjects with AD. Given the overlapping symptomologies of LBD and AD, as well as their shared association with APOE ε4, we hypothesized that these two diseases may also share this abnormal epigenetic signature in APOE.

The fourth exon of the APOE gene contains a well-defined cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) island (CGI) that harbors the two single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs; rs429358 and rs7412) which define the ε2/ε3/ε4 alleles of APOE. In addition to determining coding for the apoE protein, these two SNPs also alter CpG dinucleotides. The ε4 allele contains an additional CpG site compared to the ε3 and ε2 alleles, further increasing the density of an already CpG-rich region. In contrast, one CpG is eliminated in the ε2 allele, which opens up a 33-bp CpG-free region [5]. Thus, the two ε2/ε3/ε4-defining SNPs clearly alter the CpG content and, therefore, the epigenetic landscape of the APOE CGI. Furthermore, the APOE CGI is highly methylated in the human brain, performs important gene regulatory functions, and modulates the expression of APOE locus genes in a cell type-, DNA methylation-, and ε2/ε3/ε4 allele-specific manner [6].

We recently identified two differentially methylated regions (DMRs) of the APOE CGI, herein described as Region I and II, in which AD cases demonstrated reduced methylation compared to controls. These DMRs are tissue- and APOE genotype-specific. Of the tissues and APOE haplotypes tested in our past study, the largest decrease of methylation occurred in APOE ε3/ε4 AD frontal lobe tissue [7]. Given the associations between the APOE ε4 allele and LBD risk and progression, we hypothesized in the present study that the AD-defined DMRs of APOE might also be observable in LBD. To test this hypothesis, we quantified DNA methylation across Region I and II of the APOE CGI in PMB of APOE ε3/ε4 heterozygous carriers from four pathologically determined groups: no disease (i.e., neuropathological pure controls, [npControls]), AD alone (i.e., neuropathological pure AD, [npAD]), AD and LBD (LBD + AD), and LBD alone (i.e., neuropathological pure LBD, [npLBD]).

2. Methods

2.1. Human subjects, tissue collection, and nucleic acid processing

The use of human tissues in this study was approved by the institutional review board of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System. Autopsy materials used in this study were obtained from the University of Washington (UW) Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center Neuropathology Core, and from the NIA-supported Alzheimer’s Disease Centers at the University of Pittsburgh (AG005133), University of California at San Diego (AG005131), University of Kentucky (AG028383), and Oregon Health and Science University (AG008017). All subjects and/or their designated family members provided informed consent at their respective institutions regarding the use of these tissues.

Due to overlapping symptomologies, it is challenging to clinically distinguish between AD and LBD, and while all subjects presented with cognitive impairment, the diagnostic categories of all subjects were determined neuropathologically. Detailed systematic neuropathological assessments and subject classifications are described by Tsuang et. al [8]. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD) criteria was used to assess AD neuropathologic changes (i.e., via Braak stage and CERAD plaque score), and α-synuclein (ASN) immunohistochemistry was used to assess LB neuropathologic changes (i.e., via ASN-positive inclusions and neurites) [8–10]. npAD subjects had high level AD neuropathologic changes (Braak stage 4, 5, or 6 and a CERAD score of moderate or frequent) but no Lewy body neuropathologic changes; npLBD subjects had limbic or neorcortical Lewy body neuropathologic changes and no to low levels of AD neuropathologic changes; LBD + AD subjects met neuropathological criteria for both LBD and AD. npControl subjects were not clinically demented, did not meet the pathologic criteria for AD, and were negative for ASN-positive inclusions in the limbic and neocortical regions.

In our previous study, the largest difference in APOE CGI methylation level was between AD and control subjects with heterogeneous APOE ε3/ε4 genotypes [7]. Therefore, in this study, only subjects with an APOE ε3/ε4 genotype were selected. After applying these specific selection criteria, we identified 35 different subjects (see Table 1) from whom we were able to obtain 27 cerebellar samples and 33 frontal lobe postmortem samples.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of APOE ε3/ε4 subjects by neuropathologic diagnostic group

| Total | Control | npAD | LBD + AD | npLBD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 35 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 12 |

| Age at death: mean (SD) | 78.7 (7.5) | 81.4 (2.9) | 76.2 (5.3) | 77.8 (8.9) | 79.8 (8.5) |

| Gender: N male (% male) | 22 (63%) | 2 (40%) | 4 (67%) | 8 (67%) | 8 (67%) |

| Braak stage: mean (SD) | 4.1 (1.3) | 3.0 (0.7) | 5.3 (0.8) | 4.9 (0.7) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| Cerebellum available: N (%) | 27 (77%) | 5 (100%) | 4 (67%) | 9 (75%) | 9 (75%) |

| Frontal lobe available: N (%) | 33 (94%) | 5 (100%) | 6 (100%) | 11 (92%) | 11 (92%) |

npAD: neuropathological pure Alzheimer’s disease; LBD + AD: concomitant Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease; npLBD: neuropathological pure Lewy body disease; SD: standard deviation

Genomic DNA was isolated from frozen PMB using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nucleic acid concentrations were measured by NanoPhotometer (Implen), and samples were stored at −20°C prior to use.

2.2. Bisulfite pyrosequencing

DNA methylation levels were quantified using previously described procedures [6, 7]. Briefly, 500 ng of genomic DNA were isolated from the frontal lobe and cerebellar PMB tissue of each subject and then bisulfite converted using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen). To evaluate the methylation status of the two APOE CGI subregions, we used pyrosequencing assays that were designed to cover the 27 CpG sites that defined Region I (i.e., from the 11th CpG of the CGI to the 37th CpG) and the 10 CpG sites that defined Region II (i.e., from the 77th CpG to the 86th). Four polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers and 9 sequencing primers were designed using PyroMark Assay Design software version 2.0 (Qiagen; see Supplementary Table 1). PCR was performed on approximately 20 ng of bisulfite-converted DNA using PyroMark PCR kits (Qiagen) on a GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems). Pyrosequencing was carried out using a PyroMark Q24 system (Qiagen), and data were analyzed using PyroMark Q24 software, version 2.0.6 (Qiagen). Bisulfite treatment controls were integrated as a quality-control measure. Postmortem cerebellar tissue was selected as control tissue, as it is only mildly impacted by AD and LBD pathologies and does not show any AD-specific APOE CGI methylation changes [7].

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 13 (SPSS). For each subject/tissue combination, we measured the percentage of methylated cytosines at each of the 27 CpG sites of APOE CGI Region I and at each of the 10 CpG sites of APOE CGI Region II. To compare these overall percentages by disease status, we used a linear mixed-effects model that accounted for repeated measures on a subject across tissue types and APOE CGI regions. This model included fixed effects for disease status, tissue type, and region, as well as all second- and third-order interactions, which allowed for the effects of disease status to vary by tissue type and region. For each tissue type and region, we performed pairwise comparisons between diagnostic groups without adjusting for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. DNA methylation at the APOE CGI is decreased in npLBD

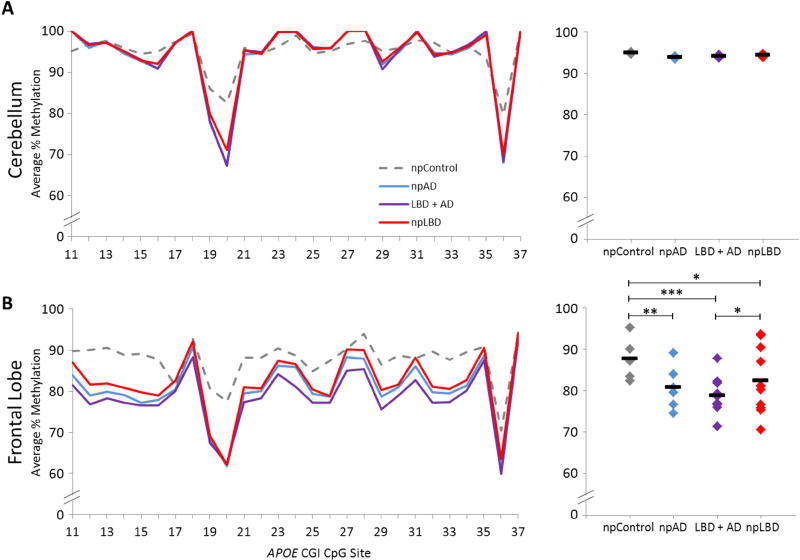

To determine whether LBD brains exhibit aberrant DNA methylation in the APOE CGI, we compared methylation differences across two subregions in PMB from npAD (n=6), LBD + AD (n=12), npLBD (n=12), and npControl (n=5) subjects. In Region I, no significant differences in DNA methylation were detected between diagnostic groups in the cerebellum, which was initially selected as control tissue (Figure 1a). However, in frontal lobe tissue, a significant reduction in Region I methylation was detected in all three disease pathologies compared to npControls; a significant reduction in Region I methylation of frontal lobe tissue was also detected in LBD + AD compared to npLBD (Figure 1b). Indeed, the concomitant LBD + AD group showed the lowest average level of Region I methylation with 78.7% ± 8.2 (mean +/− SD), followed by npAD with 80.8% ± 9.0, npLBD with 82.3% ± 10.6, and then npControls at 87.6% ± 7.4.

Fig. 1.

APOE Region I methylation in PMB tissues. DNA methylation levels of APOE Region I by disease status. Left panel: the graphs depict the average percentage of DNA methylation for npControl, npAD, LBD + AD, and npLBD subjects from (A) cerebellum and (B) frontal lobe at each of the individual 27 CpG sites tested. Right panel: the dot plots depict the mean Region I methylation for each subject (denoted by ◆) as averaged across all 27 CpG sites and the mean Region I methylation for each neuropathologic diagnostic group (denoted by a black line). P-values are based on a linear mixed-effects model (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). npAD: neuropathological pure Alzheimer’s disease; CGI: cytosine phosphate guanine island; CpG: cytosine phosphate guanine; LBD + AD: concomitant Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease; npLBD: neuropathological pure Lewy body disease

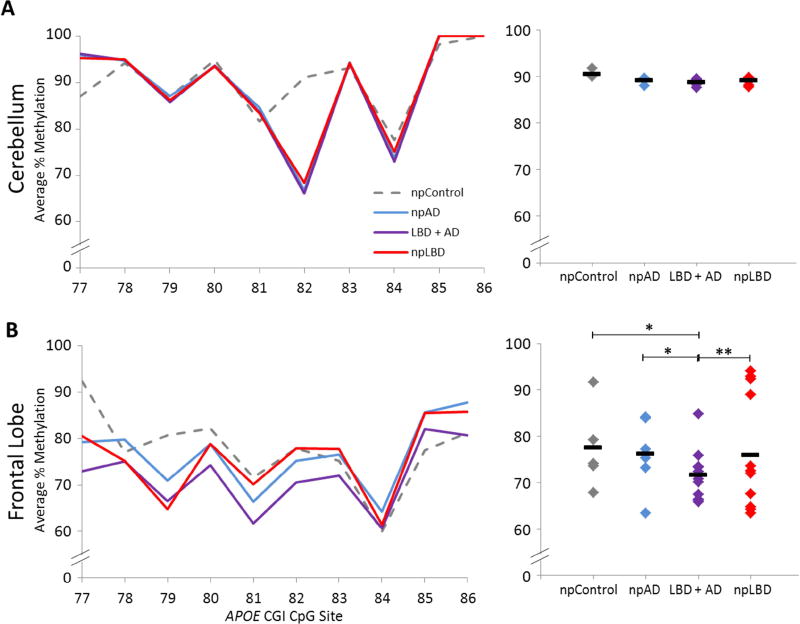

Similar trends were observed in Region II, where there were also no significant differences between diagnostic groups in the cerebellum (Figure 2a). In the frontal lobe, we observed more overlap between groups in Region II methylation than in Region I methylation, but the LBD + AD group continued to have the lowest level of methylation at 71.6% ± 9.0 (Figure 2b), which was significantly lower than the npAD (76.1% ± 10.6), npLBD (75.9% ± 14.3), and npControl (77.5% ± 15.1) groups. Data from both regions indicate that a portion of APOE CGI DNA methylation in the frontal lobe is significantly reduced in npLBD, npAD, and concomitant LBD + AD compared to npControls.

Fig. 2.

APOE Region II methylation in PMB tissues. DNA methylation levels of APOE Region II by disease status. Left panel: the graphs depict the average percentage of DNA methylation for npControl, npAD, LBD + AD, and npLBD subjects from (A) cerebellum and (B) frontal lobe at each of the individual 10 CpG sites tested. Right panel: the dot plots depict the mean Region II methylation for each subject (denoted by ◆) as averaged across all 10 CpG sites and the mean Region II methylation for each neuropathologic diagnostic group (denoted by a black line). P-values are based on a linear mixed-effects model (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). npAD: neuropathological pure Alzheimer’s disease; CGI: cytosine phosphate guanine island; CpG: cytosine phosphate guanine; LBD + AD: concomitant Lewy body disease and Alzheimer’s disease; npLBD: neuropathological pure Lewy body disease

4. Discussion

Here we show, for the first time, reduced DNA methylation levels within the APOE CGI of patients with LBD. Although the results varied somewhat between APOE Region I and II, we found a similar pattern of decreased methylation in the frontal lobe across all three disease groups. We also observed that the frontal lobes of subjects with concomitant Lewy body and AD pathologies (i.e., LBD + AD subjects) tended to have lower methylation levels than either pathology alone. It is likely that this reflects a shared epigenetic defect that is related to the overlapping molecular, cellular, and clinical aspects of LBD and AD, but it is unclear how these epigenetic changes specifically affect the etiology and/or pathophysiology of these diseases. Clinically, this shared epigenetic defect is interesting given that the combination of these two pathologies is associated with a more rapid cognitive decline than either AD or LBD alone [11, 12]. It is thus possible that this finding is indicative of a correlation between the methylation of the APOE CGI region and disease severity.

Aberrant DNA methylation has been associated with a number of neurodegenerative disorders including AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD), and LBD. Fernandez et al. showed, for example, that PMB carries distinct hypomethylated epigenetic profiles that distinguish patients with LBD from their neurologically normal counterparts [13]. Furthermore, DNMT1 nuclear sequestration has been found in patients with LBD [14], which presents a plausible mechanism for the observed loss of methylation [13]. It has also been suggested that a common core of differentially methylated sites might be a signature hallmark of all neurodegenerative diseases. To that end, Sanchez-Mut et al. found shared epigenetic aberrations in AD, PD, LBD, and Down syndrome patients [15]. Our observation of decreased methylation at the APOE CGI in both npAD and npLBD further supports this idea. However, future studies will need to perform whole-methylome methods to decipher disease-specific epigenetic profiles. On a broader scale, our findings add to the scope of data suggesting that concomitant neuropathologies should be taken into account when interpreting DNA methylation data in all disease association studies [16].

Methylation profiles of specific genes have previously been implicated in multiple neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, decreased methylation of SNCA has been associated with both LBD [17] and PD, including PD-related changes in SCNA gene expression [18, 19]. And methylation changes in ANK1 have been associated with AD [20, 21] and LBD [15]. Our data suggest that APOE can be added to the list of specific genes in which epigenetic changes are associated with multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, because PD patients with APOE ε4 allele(s) have an earlier age of onset than PD patients without APOE ε4 allele(s) [22], future APOE methylation studies in PD could be useful in deciphering the relationship between the methylation of the APOE CGI subregions and dementia as well as neurodegeneration.

Future studies should also consider the effect of other APOE genotypes in the epigenetics of LBD. As we have discussed, our decision to limit the current study to subjects with heterogeneous APOE ε3/ε4 genotypes was influenced by our previous finding that AD and control subjects with heterogeneous APOE ε3/ε4 genotypes showed the largest differences in APOE CGI methylation [7]. Although this decision resulted in significant findings with respect to npLBD and LBD + AD in our current study, fully deciphering the pathophysiological links between APOE genotype, local methylation, disease risk, and neurodegenerative progression will require investigations that include subjects with other APOE genotypes.

As expected, our study found no significant effect of disease on cerebellar APOE CGI methylation, thereby emphasizing our previous finding that these methylation changes are specific to pathologically impacted brain regions. Unfortunately, this presents a challenge when studying such methylation changes, as PMB are difficult to obtain. In this study, for example, after applying strict age (> 65), APOE genotype (ε3/ε4), and clinical/autopsy diagnostic criteria, we were only able to obtain 5 control frontal lobe samples. Studying peripheral DNA sources such as whole blood would be preferable; however, unpublished data from our lab suggest that such tissues are not relevant to the APOE DMRs.

The one puzzling finding in this study is that we did not observe a significant methylation difference between npAD cases and npControls in Region II. In fact, both of the APOE CGI subregions that were examined in this study were originally selected because of the different methylation levels we observed between AD cases and controls in these regions [7], and thus, we would expect to observe similar differences in this study. A likely explanation for this divergence is that the number of npAD cases included in the current study was insufficient to detect a significant difference. Indeed, our previous study included nearly twice as many AD cases and controls [7]. Additionally, Lewy body neuropathology was not consistently screened for in our prior studies, and concomitant LBD in AD subjects in our previous study could explain the difference between the two studies. Despite the variability between studies, this negative finding highlights the difference between these two subregions and suggests that Region I might be a more sensitive biomarker for distinguishing between demented and non-demented subjects whereas Region II might be more useful in distinguishing between different dementia-related diseases. Moreover, this work supports the overall idea that epigenetics play an important pathophysiological role in APOE-related neurodegenerative disease risk.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A pioneer study identifies a potential epigenetic mark of LBD brain

APOE DNA methylation levels are altered in LBD frontal cortex

LBD and AD share common epigenetic aberrancies in the APOE gene

Research in Context.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW

Similar to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), inheritance of the ε4 allele of the Apolipoprotein E gene (APOE) increases a person’s risk for Lewy body dementia (LBD), yet the mechanisms are poorly studied. We searched PubMed for articles on DNA methylation in LBD and APOE and cited all relevant work.

INTERPRETATION

In neuropathologic pure postmortem brain we found altered APOE DNA methylation in AD and LBD, with an even greater aberration in concomitant LBD + AD. This shared epigenetic defect parallels clinical observations in which the combination of these pathologies is associated with a more rapid cognitive decline than either alone.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This APOE epigenetic aberration may relate to the overlapping molecular, cellular, and clinical aspects of LBD and AD. Two crucial questions remain, (i) what is the relationship between APOE genotype and local DNA methylation (ii) how does APOE methylation affect the etiology and/or pathophysiology of these diseases?

Acknowledgments

We thank the subjects and their families who consented for the use of their brain tissues.

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research Program. Brain tissues were obtained from donors to the following research centers: University of Washington (UW) Neuropathology Core, which is supported by the Alzheimer's Disease Research Center (AG05136), and the NIA supported Alzheimer's Disease Centers at the University of Pittsburgh (AG005133), University of California at San Diego (AG005131), University of Kentucky (AG028383), and Oregon Health and Science University (AG008017).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts

We report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Molecular imaging biomarkers for dementia with Lewy bodies: an update. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:555–77. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane R, He Y, Morris C, Leverenz JB, Emre M, Ballard C. BuChE-K and APOE epsilon4 allele frequencies in Lewy body dementias, and influence of genotype and hyperhomocysteinemia on cognitive decline. Mov Disord. 2009;24:392–400. doi: 10.1002/mds.22357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bras J, Guerreiro R, Darwent L, Parkkinen L, Ansorge O, Escott-Price V, et al. Genetic analysis implicates APOE, SNCA and suggests lysosomal dysfunction in the etiology of dementia with Lewy bodies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6139–46. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keogh MJ, Kurzawa-Akanbi M, Griffin H, Douroudis K, Ayers KL, Hussein RI, et al. Exome sequencing in dementia with Lewy bodies. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e728. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu CE, Foraker J. Epigenetic considerations of the APOE gene. Biomol Concepts. 2015;6:77–84. doi: 10.1515/bmc-2014-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu CE, Cudaback E, Foraker J, Thomson Z, Leong L, Lutz F, et al. Epigenetic signature and enhancer activity of the human APOE gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2013 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foraker J, Millard SP, Leong L, Thomson Z, Chen S, Keene CD, et al. The APOE Gene is Differentially Methylated in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48:745–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuang DW, Wilson RK, Lopez OL, Luedecking-Zimmer EK, Leverenz JB, DeKosky ST, et al. Genetic association between the APOE*4 allele and Lewy bodies in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:509–13. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150892.81839.D1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marui W, Iseki E, Kato M, Akatsu H, Kosaka K. Pathological entity of dementia with Lewy bodies and its differentiation from Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:121–8. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0869-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leverenz JB, Hamilton R, Tsuang DW, Schantz A, Vavrek D, Larson EB, et al. Empiric refinement of the pathologic assessment of Lewy-related pathology in the dementia patient. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:220–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraybill ML, Larson EB, Tsuang DW, Teri L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, et al. Cognitive differences in dementia patients with autopsy-verified AD, Lewy body pathology, or both. Neurology. 2005;64:2069–73. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000165987.89198.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung EJ, Babulal GM, Monsell SE, Cairns NJ, Roe CM, Morris JC. Clinical Features of Alzheimer Disease With and Without Lewy Bodies. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:789–96. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez AF, Assenov Y, Martin-Subero JI, Balint B, Siebert R, Taniguchi H, et al. A DNA methylation fingerprint of 1628 human samples. Genome Res. 2012;22:407–19. doi: 10.1101/gr.119867.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desplats P, Spencer B, Coffee E, Patel P, Michael S, Patrick C, et al. Alpha-synuclein sequesters Dnmt1 from the nucleus: a novel mechanism for epigenetic alterations in Lewy body diseases. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9031–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.212589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Mut JV, Heyn H, Vidal E, Moran S, Sayols S, Delgado-Morales R, et al. Human DNA methylomes of neurodegenerative diseases show common epigenomic patterns. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e718. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang J, Yu L, Gaiteri C, Srivastava GP, Chibnik LB, Leurgans SE, et al. Association of DNA methylation in the brain with age in older persons is confounded by common neuropathologies. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;67:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Funahashi Y, Yoshino Y, Yamazaki K, Mori Y, Mori T, Ozaki Y, et al. DNA methylation changes at SNCA intron 1 in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71:28–35. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jowaed A, Schmitt I, Kaut O, Wullner U. Methylation regulates alpha-synuclein expression and is decreased in Parkinson's disease patients' brains. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6355–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6119-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto L, Takuma H, Tamaoka A, Kurisaki H, Date H, Tsuji S, et al. CpG demethylation enhances alpha-synuclein expression and affects the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, et al. Alzheimer's disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci. Nat Neurosci. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nn.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunnon K, Smith R, Hannon E, De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Volta M, et al. Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1164–70. doi: 10.1038/nn.3782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zareparsi S, Camicioli R, Sexton G, Bird T, Swanson P, Kaye J, et al. Age at onset of Parkinson disease and apolipoprotein E genotypes. Am J Med Genet. 2002;107:156–61. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.