Abstract

Background & Aims

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and transient elastography (TE) are noninvasive techniques used to detect liver fibrosis in NAFLD. MRE detects fibrosis more accurately than TE, but MRE is more expensive, and the concordance between MRE and TE have not been optimally assessed in obese patients. It is important to determine under which conditions TE and MRE produce the same readings, so that some patients can simply undergo TE evaluation to detect fibrosis. We aimed to assess the association between body-mass-index (BMI) and discordancy between MRE and TE findings, using liver biopsy as the reference, and validated our findings in a separate cohort.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional study of 119 adults with NAFLD who underwent MRE, TE with M and XL probe, and liver biopsy analysis from October 2011 through January 2017 (training cohort). MRE and TE results were considered to be concordant if they found patients to have the same stage fibrosis as liver biopsy analysis. We validated our findings in 75 adults with NAFLD who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy at a separate institution from March 2010 through May 2013. The primary outcome was rate of discordance between MRE and TE in determining stage of fibrosis (stage 2–4 vs 0–1). Secondary outcomes were the rate of discordance between MRE and TE in determining dichotomized stage of fibrosis (1–4 vs 0, 3–4 vs 0–2, and 4 vs 0–3).

Results

In the training cohort, there was 43.7% discordance in findings from MRE vs TE. BMI associated significantly with discordance in findings from MRE vs TE (odds ratio, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.15–2.51; P=.008) after multivariable adjustment by age and sex. The findings were confirmed in the validation cohort: there was 45.3% discordance in findings from MRE vs TE. BMI again associated significantly with discordance in findings from MRE vs TE (odds ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.04–2.21; P=.029) after multivariable adjustment by age and sex.

Conclusion

We identified and validated BMI as a factor significantly associated with discordance of findings from MRE vs TE in assessment of fibrosis stage. The degree of discordancy increases with BMI.

Keywords: imaging, comparison, liver stiffness measurement, prognostic factor, liver fibrosis, obesity, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, magnetic resonance elastography, transient elastography

INTRODUCTION

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is currently one of the most prevalent causes of chronic liver disease worldwide and is estimated to affect approximately one-third of the adult population in the United States1. Recent studies have suggested that presence of liver fibrosis especially significant liver fibrosis (stage≥2) portends a worse prognosis in NAFLD 2–4 and that long-term liver related events increase with increase in fibrosis stage 4. Therefore, the detection of significant liver fibrosis is important and clinically relevant for the management of patients with NAFLD4.

Transient elastography (TE; FibroScan®) allows rapid, bed-side liver stiffness measurements (LSM). TE has been shown to correlate with stage of fibrosis, particularly in severe fibrosis and cirrhosis 5, 6. Although the use of conventional M probe is limited by a high technical failure rate in individuals with body mass index (BMI) above 28 kg/m2, the use of XL probe has shown to reduce the failure rate for measuring fibrosis in obese patients 7–9. On the other hand, MRE has been demonstrated to accurately diagnose fibrosis in NAFLD patients 10, 11 and to be accurate and effective in patients with obesity 9, 12, 13. However, an MRI-based technique like MRE is often regarded as more expensive than an ultrasound-based technique such as TE.

The optimal clinical approach for non-invasive detection of liver fibrosis in NAFLD remains unclear especially in patients with higher BMI 14. Studies have demonstrated that MRE is more accurate than TE for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients 15, 16, but the key unmet need in the field is to assess when TE gives the same reading as MRE so that in the future we do not need to perform MRE in those patients where TE provides similar degree of accuracy for the detection of fibrosis. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis in a training cohort and a validation cohort to fill this gap in knowledge.

Using a well-characterized, prospective cohort of American adults with suspected NAFLD derived from the UCSD NAFLD Cohort, who underwent contemporaneously a liver biopsy, MRE and TE measurement with M and XL probes, we aimed at assessing the association between BMI and the discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) using liver biopsy as the gold standard. We then validated our findings using an independent validation cohort including 75 prospectively recruited obese patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD derived from the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study participant and design in UCSD training cohort

This study included consecutively a training cohort derived from a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective UCSD NAFLD Cohort of 119 adults with suspected NAFLD who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy from October 2011 through January 2017. All patients with suspected NAFLD with a clinical indication for liver biopsy underwent a careful evaluation for other causes of hepatic steatosis and liver disease. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients and this study was approved by the UCSD Institutional Review Board and the Clinical and Translational Research Institute.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria for the USCD NAFLD Cohort

Participants were included in the study if they were 18 years or older with suspected NAFLD and were willing and able to provide informed consent, please see Supplementary Material for detailed exclusion criteria.

Histologic Evaluation in USCD NAFLD Cohort

All liver biopsies were performed by an experienced liver pathologist who was blinded to the patient’s clinical and radiological data. The NASH-CRN Histologic Scoring System 17 was used to assess liver fibrosis classified into five stages (0–4). Please see Supplementary Material for additional details.

Magnetic Resonance Elastography in USCD NAFLD Cohort

MRE was performed at the UCSD MR3T Research Laboratory using the 3T research scanner (GE Signa EXCITE HDxt; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and is fully detailed in the Supplementary Material.

Transient Elastography in USCD NAFLD Cohort

TE was performed by a trained technician, blinded to clinical and histologic results, using the FibroScan® 502 Touch model (Echosens, Paris, France). Detailed methods have been previously-described in references 16 and are detailed in Supplementary Material.

Mayo Clinic NAFLD validation cohort

The Mayo Clinic NAFLD cohort included 75 adults with NAFLD who underwent contemporaneous MRE, TE, and liver biopsy from March 2010 through May 2013. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients and this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. The data was retrieved from a previously published study 9 and the data extraction flow-chart is provided in Supplemental Figure 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria for the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort

Participants were included in the study if they were 18 years or older with NAFLD verified with liver histologic examination within at least 48 hours, but no later than 1 month, of study enrollment and were willing and able to provide informed consent. Please see Supplementary material for detailed exclusion criteria.

Histologic Evaluation of Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort

Liver biopsy was performed by using either a percutaneous needle biopsy or subcapsular wedge biopsy as per standard of care. The Brunt classification was used to assess liver fibrosis classified into five stages (0–4). Please see Supplemental Material for additional details.

Magnetic Resonance Elastography of Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort

MRE were performed at the Mayo Clinic using a 1.5-T whole-body MR imaging unit with a 60-cm bore (Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, Wis) with all participants in the supine position, please see Supplementary Material for additional details.

Transient Elastography of Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort

TE was performed by a trained technician, blinded to clinical and histologic results, using the FibroScan® (Echosens, Paris, France), please see Supplementary Material for additional details.

Outcome measures

MRE and TE were considered in concordance for the stage of fibrosis if they both correctly stage the fibrosis according to liver biopsy assessment. Thus, the concordance-rate was defined by individuals with concordant MRE and TE for the stage of fibrosis using liver biopsy as gold standard. The discordance-rate was defined by default as all non-concordant individuals.

The primary outcome was discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of significant fibrosis (stage 2–4 versus 0–1) using the liver biopsy as the gold standard. Secondary outcomes was the discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of dichotomized stage of fibrosis (1–4 versus 0, 3–4 versus 0–2, and 4 versus 0–3) using the liver biopsy as the gold standard.

Statistical Analyses

Patients’ demographic data, laboratory, and imaging data were summarized with mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and with numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Mean and frequency were compared using an independent samples t-test or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test or Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact Test, where appropriate. Unreliable measurements was defined as success rate <60% and/or number of valid measurement <10 and/or IQR/median LSM >30%18. The unreliable LSM were classified in the discordant group as the study aimed at assessing when TE gives the same reading as MRE so that there is no need to perform MRE in those patients in future. Thus, unreliable LSM needed to be considered and the analysis was performed in intention to diagnose.

The thresholds of MRE and TE used for the dichotomized stage of liver fibrosis were previously determined in each cohort respectively 9, 16 : the threshold used for classification of liver fibrosis stage 2–4 versus 0–1 using TE were 7.80 kPa, and 6.90 kPa; and using MRE were 3.50 kPa and 2.86 kPa in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort and UCSD NAFLD Cohort respectively.

The odds ratios were determined using univariate and multi-adjusted logistic regression. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or SPSS (IBM, Chicago, IL). A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of USCD NAFLD Cohort

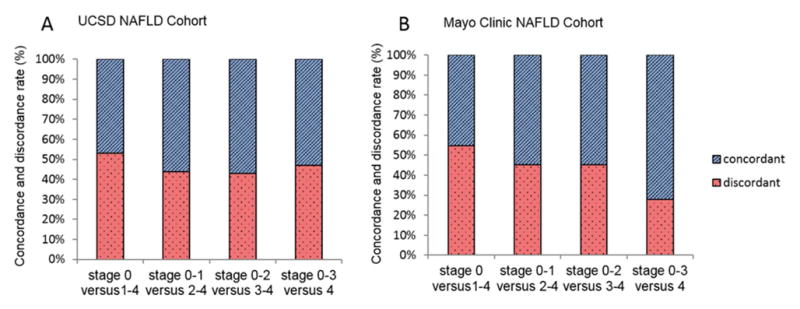

The training cohort included 119 individuals (54.6% female) with mean (±standard deviation (SD)) age and BMI of 49.8 (±14.5) years and 30.6 (±5.1) kg/m2, respectively. The 119 TE were performed using either M probe (n= 66, 55.5%) or XL probe (n=53, 44.5%) when appropriate. The discordance-rate between MRE and TE using liver biopsy as the gold standard for the stage of significant liver fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) was 43.7% (n=52) Figure 1A, the type of discordancy in provided in Supplemental Figure 3A. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1. Concordance and discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of liver fibrosis.

Concordance and discordance-rate are presented as percentage of the total cohort A. in the USCD NAFLD Cohort (total n=119); B. in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort (total n=75).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by MRE and TE concordance in the UCSD NAFLD Cohort

| Characteristics | All (n=119) | TE and MRE concordant (n=67) | TE and MRE discordant (n=52) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 49.8 (14.5) | 48.4 (15.2) | 51.7 (13.4) | 0.219 |

| Female, n (%) | 65 (54.6) | 35 (52.2) | 30 (57.7) | 0.553 |

| White, n (%) | 57 (47.9) | 32 (47.8) | 25 (48.1) | 0.972 |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | 35 (29.4) | 17 (25.4) | 18 (34.6) | 0.272 |

| Clinical | ||||

| Type 2 Diabetes, n (%) | 44 (37.0) | 22 (32.8) | 22 (42.3) | 0.288 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.6 (5.1) | 29.5 (4.6) | 32.0 (5.5) | 0.009 |

| Biological data | ||||

| AST (U/L) | 37.0 (24.8) | 39.1 (30.5) | 34.4 (14.5) | 0.311 |

| ALT (U/L) | 53.0 (44.0) | 56.8 (54.9) | 48.1 (23.4) | 0.290 |

| Alk P (U/L) | 74.1 (32.9) | 72.2 (36.0) | 76.7 (28.4) | 0.460 |

| GGT (U/L) | 54.9 (60.6) | 54.7 (53.9) | 55.1 (69.0) | 0.976 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.51 (0.26) | 0.56 (0.27) | 0.50 (0.29) | 0.235 |

| Direct Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.15) | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.127 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.5 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.3) | 0.056 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 110.4 (39.4) | 113.8 (44.4) | 106.0 (31.7) | 0.248 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.0 (1.2) | 6.0 (0.9) | 0.969 |

| Insulin (U/ml) | 26.6 (21.8) | 27.2 (26.2) | 25.9 (14.7) | 0.788 |

| HOMA-R | 7.8 (1.1) | 8.7 (13.3) | 6.7 (4.8) | 0.363 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 168.9 (109.2) | 167.0 (124.5) | 167.5 (87.9) | 0.903 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 185.6 (39.1) | 187.0 (39.2) | 183.8 (39.3) | 0.663 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 50.0 (18.3) | 51.4 (20.6) | 48.3 (15.0) | 0.358 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 103.8 (33.2) | 105.4 (35.0) | 101.8 (31.2) | 0.566 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 236.2 (63.9) | 235.4 (67.3) | 237.3 (59.7) | 0.872 |

| Prothrombin time | 10.8 (1.0) | 10.9 (1.1) | 10.8 (0.8) | 0.060 |

| INR | 1.02 (0.09) | 1.03 (0.10) | 1.02 (0.08) | 0.002 |

| Histology | ||||

| Fibrosis | 0.448 | |||

| 0 | 54 (45.4) | 35 (52.2) | 19 (36.5) | |

| 1 | 31 (26.1) | 14 (20.9) | 17 (32.7) | |

| 2 | 14 (11.8) | 7 (10.4) | 7 (13.5) | |

| 3 | 12 (10.1) | 6 (9.0) | 6 (11.5) | |

| 4 | 8 (6.7) | 5 (7.5) | 3 (5.8) | |

| Steatosis | 0.473 | |||

| 0 | 9 (7.6) | 4 (6.2) | 5 (9.6) | |

| 1 | 57 (47.9) | 34 (52.3) | 22 (42.3) | |

| 2 | 35 (29.4) | 20 (30.8) | 15 (28.8) | |

| 3 | 17 (14.3) | 7 (10.8) | 10 (19.2) | |

| Lobular inflammation | 0.592 | |||

| 0 | 6 (5.0) | 4 (6.3) | 2 (3.9) | |

| 1 | 60 (50.4) | 31 (48.4) | 29 (56.9) | |

| 2 | 45 (37.8) | 25 (39.1) | 19 (37.3) | |

| 3 | 5 (4.2) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Ballooning | 0.379 | |||

| 0 | 52 (43.7) | 32 (50.8) | 19 (38.0) | |

| 1 | 49 (41.2) | 24 (38.1) | 25 (50.0) | |

| 2 | 13 (10.9) | 7 (11.1) | 6 (12.0) | |

| NASH, | 0.723 | |||

| NAFLD, no NASH n (%) | 36 (30.2) | 22 (32.8) | 14 (26.9) | |

| Borderline NASH n (%) | 50 (42.0) | 28 (41.8) | 22 (42.3) | |

| Definite NASH n (%) | 33 (27.7) | 17 (25.4) | 16 (30.8) | |

| NAS | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.63 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.5) | 0.388 |

| Imaging data | ||||

| MRE kPa | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.9 (0.9) | 0.054 |

| Liver stiffness (kPa) | ||||

| Median, median (IQR) | 5.90 (4.0) | 5.55 (3.0) | 6.30 (4.0) | 0.031 |

| IQR, median (IQR) | 0.80 (1.05) | 0.70 (0.95) | 0.80 (1.40) | 0.480 |

| IQR/M, median (IQR) | 0.15 (0.10) | 0.14 (0.07) | 0.15 (0.14) | 0.791 |

| Unreliable liver stiffness**, n (%) | 12 (10.1) | 0 (0.00) | 12 (23.1) | <0.001 |

| CAP (dB/m) | ||||

| Median, median (IQR) | 304.0 (82.5) | 298.5 (81.7) | 306.0 (78.5) | 0.241 |

| IQR, median (IQR) | 31.0 (26.5) | 33.0 (23.2) | 27.0 (25.5) | 0.292 |

P-value determined by comparing characteristics of concordant and discordant individuals for MRE and TE using an independent samples t-test or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact Test, when appropriate, was used to compare categorical variables. Bold indicates significant P values <0.05.

Baseline characteristics of the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort for validation

The validation cohort from the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort included 75 individuals (66.7% female) with mean age (±SD) age and BMI of 47.68 (±11.51) years and 41.7 (±7.1) kg/m2, respectively. The discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) was 45.3% (n=34) Figure 1B, the type of discordancy in provided in Supplemental Figure 3B. Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics stratified by MRE and TE concordance in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort

| Characteristics | All (n=75) | TE and MRE concordant (n=41) | TE and MRE discordant (n=34) | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 47.68 (11.51) | 47.73 (11.39) | 47.62 (11.8) | 0.966 |

| Female, n (%) | 50 (66.7) | 29 (53.6) | 21 (61.7) | 0.412 |

| Clinical | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 41.7 (7.1) | 40.0 (7.0) | 43.5 (6.8) | 0.031 |

| Biological data | ||||

| AST (U/L) | 59.8 (90.6) | 72.3 (119.9) | 45.5 (33.4) | 0.328 |

| ALT (U/L) | 79.0 (103.80) | 89.5 (133.0) | 67.8 (61.9) | 0.556 |

| Alk P (U/L) | 89.2 (27.1) | 95.0 (33.4) | 83.1 (17.3) | 0.243 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.20 (0.40) | 4.19 (0.44) | 4.21 (0.35) | 0.915 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 220.26 (71.8) | 217.4 (83.1) | 224.1 (54.1) | 0.709 |

| INR | 1.26 (0.90) | 1.45 (1.1) | 0.99 (0.1) | 0.272 |

| Histology | ||||

| Fibrosis | 0.016 | |||

| 0 | 33 (44.0) | 21 (51.2) | 12 (35.3) | |

| 1 | 22 (29.3) | 11 (26.8) | 11 (32.4) | |

| 2 | 9 (12.0) | 2 (4.9) | 7 (20.6) | |

| 3 | 3 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.8) | |

| 4 | 8 (10.7) | 7 (17.1) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Imaging data | ||||

| MRE kPa | 3.17 (1.54) | 3.3 (2.0) | 3.0 (0.7) | 0.029 |

| Liver stiffness (kPa) | ||||

| Median, median (IQR) | 6.40 (4.32) | 5.80 (3.27) | 8.72 (3.76) | <0.001 |

| IQR, median (IQR) | 0.97 (0.84) | 0.92 (0.81) | 1.07 (1.42) | 0.153 |

| IQR/M, median (IQR) | 0.13 (0.11) | 0.14 (0.09) | 0.11 (0.13) | 0.466 |

| Unreliable liver stiffness*, n (%) | 14 (18.7) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (41.2) | <0.001 |

P-value determined by comparing characteristics of concordant and discordant individuals for TE and MRE using an independent samples t-test or Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test. Chi-square test or Fisher’s Exact Test, where appropriate, was used to compare categorical variables. Bold indicates significant P-values <0.05.

The distribution of the MRE and TE measurements among the concordant and discordant group in both cohorts is represented in Supplemental Figure 2.

BMI is a predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of fibrosis

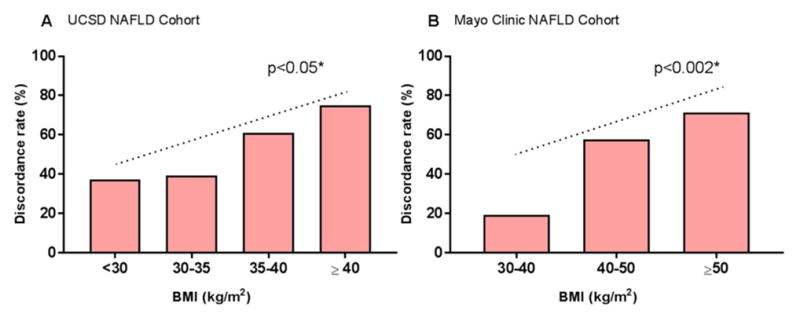

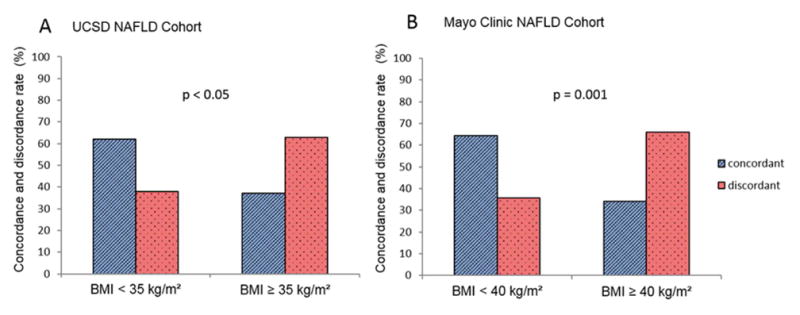

The BMI was a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant liver fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) in the univariate analysis with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.626 (95%CI:1.116–2.370, p-value= 0.0113) in the UCSD NAFLD Cohort Table 3. After multivariable-adjustment by age and sex, the BMI remained a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant liver fibrosis with an OR for 5-units increase of 1.694 [95%CI,1.145–2.507,p-value=0.008]. The discordance-rate between MRE and TE increased along with the increase in BMI (p-for-trend= 0.0309) Figure 2A. In addition, the discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the diagnosis of fibrosis was significantly higher in participant with BMI≥35 kg/m2 compared participant with BMI<35 kg/m2 (63.0% versus 38.0%,p=0.022) in the UCSD NAFLD Cohort Figure 3A. The distribution of the BMI across the discordant and concordant group is provided in Supplemental Figure 4A.

Table 3.

Predictive factor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of liver fibrosis

| Factor | OR | 95%CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCSD NAFLD Cohort | |||

| BMI ( 5 unit increase) | 1.626 | (1.116,2.370) | 0.0113 |

| Age | 1.016 | (0.991, 1.043) | 0.218 |

| Sex (Male versus Female) | 0.802 | (0.387, 1.664) | 0.554 |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic) | 1.572 | (0.709–3.486) | 0.265 |

| Type 2 Diabetes (yes versus no) | 1.500 | (0.708–3.176) | 0.289 |

| AST/ALT (one unit increase) | 0.857 | (0.204–3.599) | 0.833 |

| CAP above versus below median (≤305.0) | 1.744 | (0786–3.866) | 0.171 |

| Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort | |||

| BMI ( 5 unit increase) | 1.469 | (1.019,2.116) | 0.0391 |

| Age | 0.999 | (0.960–1.040) | 0.966 |

| Sex (Male versus Female) | 1.496 | (0.570–3.926) | 0.413 |

P-value determined by univariate logistic regression. Bold indicates significant p-values <0.05.

Figure 2. Discordance-rate between MRE and TE increases as the BMI increases.

Discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of liver fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) represented in percentages of individuals across BMI category A. in the UCSD NAFLD Cohort and B. in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort. *P value for trend determined using a Cochran-Armitage test for trend.

Figure 3. Discordancy between MRE and TE is significantly is higher in severe obese individuals.

Concordance and discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of liver fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1) as presented as percentage of A. individual with BMI < 35kg/m2 (n=92) compared to individuals with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 (n=27) in the UCSD Cohort. B. non-morbid obese (n=28) compared to morbid-obese (n=47) individuals. P-value determined using a Pearson Chi-square test.

The association between the BMI and the discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant liver fibrosis was then validated in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort which included mainly obese individuals. The BMI was a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant liver fibrosis in the univariate analysis with an OR of 1.469 (95%CI:1.019–2.116, p-value= 0.0391) Table 3. After multivariable-adjustment by age and sex, the BMI remained a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE with an OR for 5-units increase: 1.520 [95%CI:1.044–2.213,p-value=0.029]. As observed in the UCSD NAFLD Cohort, the discordance-rate between MRE and TE increased along with the increased in BMI (p-for-trend= 0.0011) in the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort Figure 2B. In addition, the discordance-rate between MRE and TE for the stage of fibrosis was significantly higher in morbid obese individuals compared to non-morbid obese individuals (66.0% versus 35.7%, p=0.001) Figure 3B. The distribution of the BMI across the discordant and concordant group is provided in Supplemental Figure 4B.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted sensitivity analysis to further assess if the type of probe used for TE assessment influenced the impact of obesity for the discordancy between MRE and TE. The distribution of M and XL probe used for TE assessment was not significantly different across the concordant and discordant group in both UCSD NAFLD cohort and the Mayo Clinic NAFLD Cohort Supplemental Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

Using two independent prospective cohorts of well-characterized patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD, this study demonstrates the BMI is a significant factor of discordancy between MRE and TE for the stage of significant fibrosis (2–4 versus 0–1). Furthermore, this study showed that the grade of obesity is also a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE as the discordance-rate between MRE and TE increases with the increase in BMI. In the context of the high prevalence of obesity in NAFLD, these results have important implications in developing an optimal clinical approach for non-invasive screening of liver fibrosis in NAFLD. Further cost-effectiveness studies are needed to determine the optimal approach for the detection of liver fibrosis taking into account the higher risk of liver fibrosis and the higher discordance-rate when the BMI increases.

In context with published literature

The detection of significant liver fibrosis (≥2) is an important feature of NAFLD as significant stage of fibrosis, even in the absence of advanced fibrosis (stages 3–4), compared to no fibrosis was shown to be associated with increased mortality or liver transplantation rate in NAFLD patients 2, 4. Therefore, NAFLD patients would benefit of an early diagnosis of significant stage of fibrosis.

Studies including population with different range of BMI have demonstrated that MRE is more accurate than TE for diagnosing liver fibrosis in NAFLD 9, 15, 16. Imajo and colleagues has shown that MRE is more accurate than TE for diagnosing significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in Japanese cohort (mean BMI: 28.1kg/m2). In the USCD Cohort including participant with higher BMI (mean: 30.4 kg/m2), we have demonstrated that MRE is more accurate than TE for diagnosing any fibrosis 16. Finally, in the Mayo Clinic Cohort including severe obese adults with liver disease caused mainly by NAFLD, the accuracy of MRE was higher than TE for diagnosing significant fibrosis and advanced fibrosis 9. Given the different range of BMI across these 3 studies, the association between BMI and the discordancy between TE and MRE could not have been fully assessed. This study provides evidence that the BMI is a significant predictor of discordancy between MRE and TE in 2 independent cohorts encompassing a large range of BMI and using M or XL probes for TE assessment when appropriate.

Severe obesity is associated with a higher skin-to-capsule-distance (SCD) which is a major cause of unreliable LSM using standard M probes. The use of the XL probes generating a lower frequency reduces the failure rate of LSM in obese patients 7, 8. Despite the use of XL probe when appropriate, our study demonstrates that the discordancy between MRE and TE increases with increase of the BMI. Although, the SCD was not measured in our study, these results suggest that the lower ultrasound frequency generated by the XL probe may not be sufficient to accurately assess LSM when the SCD increases especially when the BMI is higher than 35kg/m2. In addition, the optimum positioning of the probe in individual with severe obesity may be more difficult and less reproducible. Hence, the variability and IQR of the LSM may significantly increase when the BMI increases 19. Although TE has excellent inter- and intra-operator reproducibility in non-obese population 20, there is no data regarding the sampling variability and inter-observer variability in NAFLD population with higher BMI. In addition, XL probe tend to generate lower LSM than M probe in the same patient which suggest the need to define specific cut-offs depending on the type of probe used 7, 8. Finally, TE assesses a limited spot of the liver measured whereas MRE include a larger area, which may reduce sampling variability due to heterogeneity of liver fibrosis 21.

Strengths and limitations

There are several notable strengths of this study including a training cohort and a validation cohort, both prospectively recruited and well-characterized by experienced investigators at dedicated research centers specialized for both clinical and radiologic research. All participants of the training cohort derived from the UCSD NAFLD Cohort, underwent a systematic and standardized liver disease assessment to exclude for other causes of liver disease before inclusion in the study and the liver biopsy, used as the reference standard for imaging, was scored using the well-validated NASH-CRN Histologic Scoring System. Although the liver biopsies were assessed using the Brunt classification in the Mayo Clinic, the scoring for the stage of fibrosis is similar in these two methods and thus can be compared. Although the liver biopsy accuracy has been questioned due to sampling errors and variable intra- and inter-observer agreement 21, 22, it remains the gold standard for assessing liver fibrosis and thus we used the liver biopsy as reference in our study.

However, we acknowledge following limitations of this study. This study was conducted at a highly specialized tertiary care centers using advanced MRI techniques that may not be available in other clinical center. Thus the generalizability of these findings in other clinical settings is unknown. In addition, both cohorts included a relative small proportion of individuals with advanced fibrosis (stage 3–4) and spectrum variability cannot be excluded. However, the UCSD cohort has consecutively enrolled patient with suspected NAFLD indicated for a liver biopsy and the proportion of individuals with advanced fibrosis of the cohort reflects the spectrum of the disease. Therefore the results of the study are unlikely to be biased by the fibrosis stage distribution. Finally, we applied the optimum thresholds of TE and MRE for the detection of fibrosis stage defined in each cohort to limit potential bias. Indeed, there are no validated thresholds for the stage of fibrosis in large NAFLD cohort and further studies are needed to determine optimum thresholds of MRE and TE using M and XL probe in NAFLD.

Implications for clinical care and future research

This study provides important insight for the management of patients with NAFLD in routine clinical practice. The integration of the BMI in the screening strategy for the non-invasive detection of liver fibrosis in NAFLD should be considered and this parameter would help to determine when MRE is not needed in future guidelines. Further cost-effectiveness studies are necessary to evaluate the clinical utility of MRE, TE and/or liver biopsy to develop optimal screening strategies for the diagnosing NAFLD-associated fibrosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: RL is supported in part by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Foundation – Sucampo – ASP Designated Research Award in Geriatric Gastroenterology and by a T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award; Funding provided by: Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc, the John A. Hartford Foundation, OM, the Association of Specialty Professors, and the American Gastroenterological Association and grant K23-DK090303. CS and RL serve as co-PIs on the grant R01-DK106419. CC is supported by grants from the Societe Francophone du Diabete (SFD), the Philippe Foundation and Monahan Foundation. RLE is supported by NIH grant EB001981.

Abbreviations

- LSM

Liver stiffness measurement

- MRE

magnetic resonance elastography

- TE

transient elastography

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- BMI

body mass index

- CAP

controlled attenuated parameter

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: Dr. Sirlin consults, advises, and is on the speakers’ bureau for Bayer. He received grants from GE Healthcare.

The Mayo Clinic and authors JC, MY and RLE have intellectual property rights and a financial interest through receipt of royalties and equity from licensing of MRE technology. Author RLE serves as uncompensated chief executive officer of Resoundant Inc. (Rochester, MN), majority-owned by Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clinic authors have control of the data collected at Mayo. The Mayo part of research has been conducted under the oversight of, and in compliance with, the Mayo Clinic Conflict of Interest Review Board.

There are no conflict of interest to declare for the other authors

Author contributions:

Cyrielle Caussy: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Jun Chen: data collection, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Mosab H. Alquraish: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Sandra Cepin: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Phirum Nguyen: patient visits, data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Carolyn Hernandez: patient visits, data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Meng Yin: data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Ricki Bettencourt: statistical analysis, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Edward R. Cachay: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Saumya Jayakumar: data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Lynda Fortney: patient visits, data collection, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission.

Jonathan Hooker: data collection, imaging analysis, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Ethan Sy: data collection, imaging analysis, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Mark A. Valasek: interpretation of liver biopsies, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Emily Rizo: patient visits, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

Lisa Richards: patient visits, critical revision of the manuscript, approved final submission

David Brenner: critical revision of the manuscript, study supervision, approved final submission

Claude B. Sirlin: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, obtained funding, study supervision, approved final submission

Richard L. Ehman: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, obtained funding, study supervision, approved final submission

Rohit Loomba: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, obtained funding, study supervision, approved final submission

All authors approved the final version of this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angulo P, Kleiner DE, Dam-Larsen S, et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):389–97. e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekstedt M, Hagstrom H, Nasr P, et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1547–54. doi: 10.1002/hep.27368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;65(5):1557–65. doi: 10.1002/hep.29085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong VW, Vergniol J, Wong GL, et al. Diagnosis of fibrosis and cirrhosis using liver stiffness measurement in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51(2):454–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.23312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh S, Muir AJ, Dieterich DT, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Role of Elastography in Chronic Liver Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1544–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong VW, Vergniol J, Wong GL, et al. Liver stiffness measurement using XL probe in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(12):1862–71. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers RP, Pomier-Layrargues G, Kirsch R, et al. Feasibility and diagnostic performance of the FibroScan XL probe for liver stiffness measurement in overweight and7777777777777777777777777777 obese patients. Hepatology. 2012;55(1):199–208. doi: 10.1002/hep.24624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Yin M, Talwalkar JA, et al. Diagnostic performance of MR elastography and vibration-controlled transient elastography in the detection of hepatic fibrosis in patients with severe to morbid obesity. Radiology. 2017;283(2):418–28. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huwart L, Sempoux C, Vicaut E, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography for the noninvasive staging of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):32–40. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loomba R, Wolfson T, Ang B, et al. Magnetic resonance elastography predicts advanced fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1920–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.27362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatesh SK, Yin M, Ehman RL. Magnetic resonance elastography of liver: technique, analysis, and clinical applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;37(3):544–55. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin M, Glaser KJ, Talwalkar JA, et al. Hepatic MR Elastography: Clinical Performance in a Series of 1377 Consecutive Examinations. Radiology. 2016;278(1):114–24. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015142141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blond E, Disse E, Cuerq C, et al. EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in severely obese people: do they lead to over-referral? Diabetologia. 2017;60(7):1218–22. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imajo K, Kessoku T, Honda Y, et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging More Accurately Classifies Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Than Transient Elastography. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(3):626–37. e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park CC, Nguyen P, Hernandez C, et al. Magnetic Resonance Elastography vs Transient Elastography in Detection of Fibrosis and Noninvasive Measurement of Steatosis in Patients With Biopsy-Proven Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):598–607. e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41(6):1313–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol. 2008;48(5):835–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zelber-Sagi S, Yeshua H, Shlomai A, et al. Sampling variability of transient elastography according to probe location. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(6):507–14. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328346c0f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraquelli M, Rigamonti C, Casazza G, et al. Reproducibility of transient elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2007;56(7):968–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):1898–906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, et al. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):1017–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.