Abstract

The clinical manifestations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reflect an aggregate of multiple pulmonary and extrapulmonary processes. It is increasingly clear that full assessment of these processes is essential to characterize disease burden and to tailor therapy. Medical imaging has advanced such that it is now possible to obtain in vivo insight in the presence and severity of lung disease-associated features. In this review, we have assembled data from multiple disciplines of medical imaging research to review the role of imaging in characterization of COPD. Topics include imaging of the lungs, body composition, and extrapulmonary tissue metabolism. The primary focus is on imaging modalities that are widely available in clinical care settings and that potentially contribute to describing COPD heterogeneity and enhance our insight in underlying pathophysiological processes and their structural and functional effects.

Keywords: body composition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, imaging, lung

INTRODUCTION

The clinical manifestations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) reflect an aggregate of multiple pulmonary and extrapulmonary processes. It is increasingly clear that full assessment of these processes is essential to characterize disease burden and to tailor therapy (23, 39). Examples of these COPD-associated features include emphysematous destruction and fibrosis of the lung parenchyma, cardiovascular disease, sarcopenia, abdominal adiposity, and osteoporosis (20, 23, 48, 58, 84). Highly effective therapies are available for many of these conditions, and yet their prevalence and role in the mortality and morbidity of those with chronic respiratory diseases is often underappreciated (22, 23, 39).

Although no imaging study is critical to the initial diagnosis and management of COPD, many patients with COPD undergo imaging for other reasons, such as lung cancer screening, screening for osteoporosis, or acute changes in their clinical status. Although these medical images are often used principally for the indication that prompted their acquisition, they also provide the opportunity to obtain in vivo insight into the presence and severity of these and other conditions (3, 15, 56, 58, 91). Exciting new areas of imaging research are focused on singular aspects of these comorbidities; however, such specialization often causes us to lose a larger view of efforts in this field. Thus, although we do not advocate the routine use of imaging in COPD without another indication, extraction of morphological information and comorbidity patterns from already available medical images acquired in routine clinical care may provide new opportunities to better characterize patients and individualize treatment in the future.

In this review, we have brought together the available information on structural and metabolic imaging with regard to its potential usefulness in improving the understanding of COPD and with particular emphasis on quantitative techniques. More specifically, we focus on the structural information obtained using routine computed tomography (CT) imaging as well as on the information on body composition from both CT imaging and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Furthermore, we briefly discuss the potential of metabolic molecular imaging using the standard positron emission tomography (PET) radiopharmaceutical fluordeoxyglucose (FDG) in COPD when available for additional scientific purpose. These three imaging modalities allow the noninvasive characterization of many of the underlying pathophysiological processes in COPD and their structural and functional effects. Of note is that although magnetic resonance imaging and optical coherence tomography have been and continue to be investigated as potential imaging techniques in COPD, none have yet found a place in routine clinical care and so are beyond the scope of this review. In addition, although ultrasound is increasingly useful in the diagnosis of acute chest diseases such as pneumothorax, and endobronchial ultrasound has been widely adopted for procedures such as lymph node biopsy, neither has been routinely used in COPD, and so they have also been excluded.

LUNG STRUCTURE

Functional, structural, and molecular imaging of the lungs, using a variety of modalities, has revealed new information regarding the complexity of COPD. This discussion will focus primarily on the role of imaging in understanding COPD, but it should be noted that there is extensive work in this area on lung cancer, interstitial lung disease, asthma, pulmonary hypertension, and other chronic lung diseases.

Computed Tomography

Contributions to phenotyping.

CT imaging utilizes X-rays to acquire a three-dimensional (3D) attenuation image of the body. The images themselves are comprised of 3D pixels or voxels, each of which has a density, typically measured in Hounsfield units (HU), that distinguishes water from air, enabling the characterization of various tissue types to that particular area. These voxels are then reconstructed to using various gray values to create the overall CT image. Although CT imaging is not indicated for the routine diagnosis or clinical staging of COPD due to the overlapping risk factors and clinical manifestations of COPD with other chest diseases such as lung cancer, it is frequently obtained for other reasons in these patients (5, 60). There are a multitude of processes evident in CT imaging of the lungs, which may be grouped by anatomic compartment, namely those that affect the parenchyma, the airways, and the vasculature.

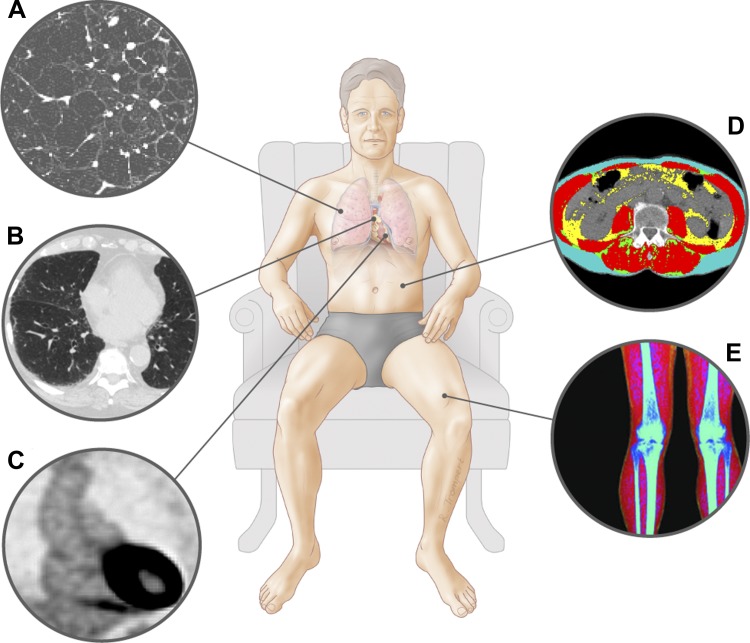

With regard to the lung parenchyma, emphysema is the most prominent anatomic and radiological COPD-associated process (Fig. 1A), and the volume, distribution, and subtype of emphysema on CT have yielded insights into the clinical management and physiology of COPD (14, 46). For instance, in the National Emphysema Treatment Trial, 1,200 COPD patients with hyperinflation were randomized to either lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) or optimal medical therapy. Although there was no overall survival benefit to LVRS, a nonprespecified subgroup analysis based on the combination of baseline CT emphysema distribution and exercise testing identified a subset of patients who responded differently to LVRS compared with medical treatment. Subjects with upper lobe or upper zone predominant emphysema and low exercise capacity had significantly lower mortality than subjects randomized to medical treatment (32). Subsequent work suggests that such clinical differences between those with upper lobe predominant or heterogeneous emphysema and more homogeneous emphysema may reflect not only anatomic differences but physiological ones as well. For instance, those with homogenous emphysema have been shown to have a greater degree of dynamic hyperinflation during exercise than those with upper lobe predominant disease, suggesting potential differences in their lung mechanics and differences in the underlying pathophysiology of their disease (11). Perhaps more importantly clinically is the role of CT in identifying patients for endobronchial lung volume reduction procedures, which are bronchoscopic alternatives to surgical LVRS, including endobronchial valves, coils, glue, and other devices. The effectiveness of endobronchial valves in particular may be limited by collateral ventilation in the setting of incomplete interlobular fissures. Collateral ventilation prevents the valves from fully deflating the target area, thus limiting their effectiveness. Small studies have suggested that CT imaging may be sensitive, albeit not necessarily specific, for the detection of the interlobular fissures, and new automated techniques may improve its performance in this area, making it an important tool for the preprocedure planning of patients undergoing endobronchial lung volume reduction (68, 69, 78).

Fig. 1.

Imaging techniques. A: thoracic CT image of patient with emphysema. B: thoracic computed tomography (CT) image of patient with interstitial lung abnormalities. C: positron emission tomography image displaying fluordeoxyglucose uptake in the aortic wall (image courtesy of Dr. Jan Bucerius). D: abdominal CT with different body composition compartments at the 3rd lumbar vertebra. E: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan leg with different body composition compartments.

Although less immediately clinically applicable, the CT identification of emphysema subtypes provides a noninvasive window into the pathophysiology of the disease and thus opens the door to additional treatment options. Smoking, the most frequent cause of emphysema, is most commonly associated with centrilobular disease and to a lesser but still significant extent with paraseptal emphysema (6, 38, 50). Additional subtypes include panlobular disease, which tends to be rare, except in patients with α1-antitrypsin deficiency or who have used certain intravenous drugs (6). Recent investigations suggest that these subtypes, including both the lobular distribution as well as severity, may have differing clinical associations (17, 18). For instance, whereas nearly all emphysema subtypes are associated with respiratory function, dyspnea, physical capacity, and annual number of exacerbations in COPD, paraseptal emphysema may be a marker of more severe clinical manifestations of the disease (18). Further CT-based investigation has shown that there may be genetic and pathophysiological reasons for such disease heterogeneity. For instance, emphysema matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are proteolytic enzymes that can break down the extracellular matrix, have been shown to be potentially important in the development of emphysema. Although some MMPs, such as MMP-3 and MMP-10, are associated with most emphysema subtypes, others, such as MMP-3 and MMP-10, have been shown to be associated with both paraseptal emphysema and more severe centrilobular disease (63). In addition, genome-wide association studies have suggested that each of the emphysema subtypes may have a somewhat unique set of genetic determinants (17). Taken together, these findings suggest the importance of CT imaging for the understanding of both the clinical manifestations and pathophysiology of the emphysematous component of COPD, especially in terms of identifying specific phenotypes of the disease.

It is increasingly clear, in large part thanks to CT imaging-based studies, that tobacco smoke exposure results in not only emphysematous but also interstitial changes in the lung, such as interstitial lung disease. In the extreme, such changes manifest radiologically and clinically as pulmonary fibrosis, but more subtle changes, often termed interstitial lung abnormalities (ILA), are as highly prevalent as ever in smokers (Fig. 1B) (8, 25, 67, 87, 88). Clinically, smokers with ILA tend to have less COPD, greater respiratory impairment, shorter 6-min walk distances, and less emphysema as measured by standard densitometry (24, 26, 87, 88). Furthermore, these abnormalities are associated with a decline in lung function and are strongly predictive of all cause and respiratory specific mortality (2, 67). Finally, ILA have been shown to be associated with a specific single-nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter region of the gene encoding mucin 5B, which has been strongly linked to the presence of more advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (41, 74). These clinical and genetic associations do not necessarily imply that all ILA will progress to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis but rather highlight the potential role of CT in identifying those COPD patients at the greatest risk for adverse events as well as its importance for understanding the complexity of smoking-related lung disease. Further work in this area could ultimately lead to the use of novel therapies such as anti-fibrotic agents in those patients with combined emphysema and early stage fibrosis.

The other lung compartment classically affected in COPD is the airways. Although usually described as being the location of chronic bronchitis, the distal small airways are likely the site of airflow limitation for COPD more generally (1, 40). These airways are below the resolution of standard clinical CT imaging; however, quantitative CT analysis of more central airways in smokers has revealed that those with smaller airway caliber and thicker airway walls tend to have lower lung function and more frequent exacerbations (37, 59, 61, 83). Although these findings are not yet clinically applicable, they may prove especially important in future phenotyping of COPD. For instance, recent work by Lange et al. (47) has shown that some individuals with COPD developed airflow limitation in early adulthood, followed by a slow decline in lung function rather than due to a rapid decline from a higher or more normal peak lung function, and it may be that those smokers who have a smaller airway caliber on CT in young adulthood are those more likely to develop COPD (4, 47).

The last lung compartment with changes evident on the CT scans of smokers is the intraparenchymal pulmonary vasculature. Pruning of the vasculature and dropout in regions of severe emphysema have long been recognized on angiographic studies, and improved CT scan resolution has made it possible to detect and quantify such changes on CT (42, 70). These changes typically include pruning of the distal vasculature and dilation of the more central vessels (30, 89, 90). Although not yet clinically available, 3D analysis of the distal pulmonary vasculature has shown that pruning of the distal vessels is associated with increased respiratory symptoms, reduced exercise capacity, impaired diffusing capacity, and multicomponent predictors of mortality (30). Further work is now ongoing to determine how metrics of pulmonary vascular morphology may be further integrated into clinical care to predict outcomes such as patient response to lung volume reduction. Of more immediate clinical importance is the appearance of the central vasculature on CT in patients with COPD. More specifically, Wells et al. (90) has shown that pulmonary artery enlargement as defined by a ratio of the diameter of the pulmonary artery to the diameter of the aorta of >1 is associated with an increased risk for severe respiratory exacerbations in patients with COPD, potentially identifying patients who will benefit the most from strategies to reduce exacerbation risk.

Advantages.

CT imaging is almost universally available in clinical care settings. It provides high-resolution insight into lung structure, and there are a multitude of methods published on the standards of image interpretation.

Limitations.

The greatest limitation to the broad utilization of CT imaging is ionizing radiation. There is an ongoing debate in the medical community about what is a safe level of such exposure. Because of this, CT manufacturers have invested a tremendous amount of resources to reduce the dose of radiation while maintaining or even improving image quality.

Clinical applications.

CT is increasingly becoming a common component to the clinical care of patients with COPD. Despite the reason for image acquisition, the biomedical community is obliged to obtain as much data as possible from these images to improve our understanding of disease and improve patient care.

BODY COMPOSITION

Alterations in body composition frequently occur in COPD, contributing to increased morbidity and mortality. In fact, up to 25% of patients with COPD have a significant loss of skeletal muscle, which has been associated with impaired exercise performance and increased mortality independent of the primary lung impairment (76, 79). However, in overweight and obese subjects, low muscle mass may not be recognized without assessment of body composition (80). Furthermore, Beijers et al. (9) recently demonstrated in normal-weight COPD patients a high prevalence of low muscle mass combined with abdominal obesity. Notably, these patients were characterized by an increased cardiometabolic risk. Clinically available imaging modalities to visualize body composition include dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and CT.

DEXA Imaging

Contribution to phenotyping.

Originally designed for osteoporosis assessment, DEXA can also be utilized to measure body composition (Fig. 1E). The underlying concept for DEXA estimation of body composition is based on assumptions regarding the difference in chemical constituents. Briefly, DEXA utilizes the variable absorption or attenuation of high- and low-energy X-ray photons to estimate the fraction of tissue occupied by fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) (43, 65). Although the details of how these measurements are made are beyond the scope of this review, it is important to note that increased tissue thickness is associated with a greater attenuation of low-energy photons than-high energy photons regardless of the tissue composition, the effect of which is a tendency for the underestimation of FM in obese subjects (36).

Recently, the European Respiratory Society task force on nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD has designated DEXA as the most appropriate tool for combined screening of osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and adipose tissue redistribution (71). Although two-compartment screening methods such as bioelectrical impedance analysis and skinfold thickness can discriminate whole body FM from FFM, DEXA is able to analyze tissue depletion and redistribution at regional levels. This is particularly useful in COPD, in which appendicular FFM has been found to be more predictive for exercise performance than whole body FFM (80). Moreover, DEXA analyses have also provided insight into some of the clinical complexity of COPD. For example, despite similar decreases appendicular FFM, whole body and trunk FFM reductions have been found to be more altered in COPD patients with CT-based emphysema compared with those without (28, 29).

In addition to differences in truncal and whole body distribution, recent advances in DEXA imaging have allowed for the differentiation between and the ratio of subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) (45, 52, 57). SAT and VAT differ in metabolic and inflammatory characteristics and the corresponding metabolic risk profile (31, 49, 77). Smoking cigarettes is a main cause of both COPD and cardiac disease, but other causes may increase the risk. For instance, cardiac disease in COPD associates with VAT (21, 51). DEXA measurements of SAT and VAT have thus far only been validated in patients without COPD. Other limitations of DEXA include the insensitivity of appendicular FFM for the detection of small loss of muscle fiber CSA, which may limit its role in monitoring subtle changes after intervention (62).

Advantages.

DEXA is particularly attractive due to low ionizing radiation, which is comparable to 1 day of normal background radiation (10). With ∼10 min of scan time, DEXA is very time efficient and convenient. It enables noninvasive insight into body composition and its potential metabolic associations.

Limitations.

Although the errors are relatively small, one has to keep in mind that the results may be influenced by conditions in which the ratio of extracellular water and intracellular water varies (e.g., severe malnutrition, edema, diuretics, aging) (66). Furthermore, this technique provides only two-dimensional projections of the body, thereby being unable to gain information about muscle groups or quantification of fat depots in the muscle. Regarding DEXA-based VAT analysis, more validation studies are warranted, as there seems to be a tendency toward overestimation of VAT (45, 52).

Clinical applicability.

DEXA is used in clinical routine care for evaluation of osteoporosis in COPD.

CT Imaging

Contribution to phenotyping.

As discussed above, CT imaging provides a wealth of information regarding lung structure and its implications for lung function in patients with COPD. Extrapulmonary findings on CT in COPD are of great scientific utility as well. Similarly to DEXA imaging, CT can also be utilized beyond its “field” to measure body composition in addition to the more traditional lung measures discussed above. This is done by measuring muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) on CT imaging, and although the standard site to measure CSA is the third lumbar vertebra (L3), this is typically outside the field of view of clinically acquired CT imaging in patients with chest diseases (Fig. 1D) (9, 73, 75, 79).

Therefore, other levels, such as L1, have been evaluated. Although single-slice CSA L3 and L1 result in significantly different whole body estimates of muscle mass, the latter may be useful to detect changes during the disease course or after intervention (73). Other sites that have been evaluated include the pectoralis muscles, where muscle CSA assessed by CT has been correlated with both objective and subjective measures of COPD severity and midthigh muscle CSA, which has been found to be strongly related to increased mortality risk (55, 56). Although such measures are not yet routinely clinically available, advances in CT segmentation technology that allow the automated detection of specific radiographic features may soon enable their more routine use.

CT is also able to quantify and evaluate the distribution of fat. For instance, CT-based analysis at the L4–L5 level revealed significantly increased VAT in the elderly with obstructive lung disease than in nonobstructive subjects, despite a comparable SAT and BMI. This adipose tissue distribution also correlated to higher interleukin-6 levels in elderly with obstructive lung disease (81), suggesting that VAT might contribute to increased plasma IL-6, which was also shown to be a strong predictor of all-cause and respiratory mortality.

Finally, patients with chronic diseases such as COPD are known to have ectopic depots of fat beyond the major subcutaneous and visceral fat storage locations, such as intramuscular adipose tissue (IMAT). Although data concerning muscle lipid content in the elderly and patients with muscle wasting disease have initially relied on muscle biopsy studies, improved resolution of CT scanners makes it now possible to noninvasively quantify IMAT (33, 35, 44). CT-derived data concerning IMAT have shown fat infiltration in intercostal muscles and midthigh muscle in normal to overweight COPD patients. This infiltration in intercostal muscles in particular is correlated with COPD severity, and patients with high midthigh IMAT tended to have lower physical activity levels (54, 64).

Advantages.

An advantage of CT is that information about body composition can be collected at the time of routine clinical imaging.

Limitations.

Muscle CSA and adipose tissue quantification may be subject to a multitude of factors, such as manufacturer, slice thickness, and pixel spacing, although their exact influence on body composition quantification is unknown. Furthermore, the radiation exposure of CT limits longitudinal research applications.

Clinical applicability.

Although CT imaging is not independently indicated for the diagnosis and management of isolated COPD, images are widely available due to their implementation in excluding other underlying pathology. Measurements of muscle CSA and adipose tissue are not yet routinely performed, but new automated techniques may enable their introduction into clinical care in the near future.

TISSUE METABOLISM

Metabolic alterations are reflected not only by body composition but also by underlying changes in tissue metabolism. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography ([18F]FDG-PET) may improve understanding of the biological processes of tissues.

[18F]FDG-PET imaging

Contribution to phenotyping.

Although DEXA and CT are informative in tissue mass quantification and distribution, they are limited in monitoring tissue metabolic activity. Standard PET imaging uses a radiolabeled glucose derivate fluordeoxyglucose (FDG) to give a 3D information on glucose metabolism in the body, enabling evaluation of local or tissue-specific metabolic features (7). There is a wide range of classical and novel radiopharmaceuticals (tracers) evaluated in (pre)clinical and experimental settings using PET. However, here, we focus on FDG-PET because of its universal availability in clinical care settings. Although PET imaging is not routinely used in the workup of COPD assessment, this method allowing quantification of tissue metabolism may be useful in scientific research to contribute to better understanding of different clinical phenotypes, as illustrated below.

FDG reflects the metabolic rate of glucose, a process reinforced in inflamed tissue, and this distinctive characteristic enables PET to evaluate adipose tissue activity in vivo. One study showed that COPD patients exhibited increased FDG uptake in visceral adipose tissue (VAT) compared with subjects without COPD. Furthermore, FDG uptake in VAT was found to predict aortic wall FDG uptake, even when adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and smoking (Fig. 1C) (12, 13, 85). It is well known that smoking tobacco is the main risk factor for development of both COPD and vascular inflammatory processes. Nevertheless, these data suggest a possible contributing role of VAT in augmenting atherosclerotic processes in COPD (84). However, further research is needed, including histological confirmation of VAT biological activity.

Several studies confirmed the presence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue (BAT) in the neck and supraclavicular region and the mediastinum as well as along the spine in healthy adults, using FDG-PET scanning and biopsy verification (19, 82). BAT activity is inversely correlated to body fat percentage in healthy adults (82). In addition, in several BAT-associated pathological conditions, such as pheochromocytoma (86) and hyperthyreoidism (53), energy expenditure is increased. Recently, it has been shown from in vitro experiments that lactate stimulates the browning of adipocytes, which is mediated by intracellular redox modifications (16). Given the hypermetabolic state observed in COPD particularly in the emphysematous phenotype (72), mitochondrial dysfunction (34, 92), and early lactate acidosis during exercise (27), increased BAT activity may be involved in energy homeostasis in COPD. However, no clinical studies that assessed BAT activity in COPD are yet available.

Advantages.

Whereas DEXA and CT provide information about structures, PET is a unique imaging tool that provides molecular imaging information. Using FDG noninvasive quantitative information of metabolic activity of tissues in vivo is acquired.

Limitations.

FDG-PET uses ionizing radiation, is not broadly available, and is more expensive than the other modalities. It is important to mention that the radiation burden is lower than in conventionally used whole body CT protocols. Additionally, factors influencing the amount of FDG uptake, such as overexpression of glucose receptors, might induce false-positive or false-negative results (7).

Clinical applicability.

F-FDG-PET imaging is not integrated in standard clinical care of COPD patients.

CONCLUSION

Over the past century, imaging has become critically important in the routine clinical care of patients, and the technologies used have advanced dramatically. The use of new analytic techniques applied to traditional imaging modalities and the development of novel imaging techniques have greatly improved the clinical care and understanding of complex diseases like COPD. These approaches, including CT, DEXA, PET, or hybrid PET-CT already aid in the noninvasive characterization of COPD phenotypes and severity, and ongoing and future work has the potential to improve our understanding of and care for this disease and the patients it affects even more. We acknowledge that, at least in the short term, some of the methods discussed above are limited to the research setting. They may improve phenotyping for clinical observational studies and clinical trials and contribute to better risk stratification and personalized medicine.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.J.S., G.R.W., and A.M.S. prepared figures; K.J.S., S.Y.A., G.R.W., F.M.M., and A.M.S. drafted manuscript; K.J.S., S.Y.A., G.R.W., F.M.M., and A.M.S. edited and revised manuscript; K.J.S., S.Y.A., G.R.W., F.M.M., and A.M.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.[No authors listed] Blue bloater: pink puffer. Br Med J 2: 677, 1968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki T, Putman RK, Hatabu H, Gao W, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Nishino M, Zazueta OE, Kurugol S, Ross JC, San José Estépar R, Schwartz DA, Rosas IO, Washko GR, O’Connor GT, Hunninghake GM. Development and Progression of Interstitial Lung Abnormalities in the Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194: 1514–1522, 2016. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201512-2523OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ash SY, Diaz AA. The role of imaging in the assessment of severe asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 23: 97–102, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ash SY, Washko GR. New lung imaging findings in chronic respiratory diseases. BRN Rev 3: 121–135, 2017. doi: 10.24875/BRN.M17000011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ash SY, Washko GR. The value of CT scanning, In: Controversies in COPD, edited by Anzueto A, Heijdra Y, and Hurst JR. Sheffield, UK: European Respiratory Society, 2015, p. 121–133, doi: 10.1183/2312508X.10019214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Austin JH, Müller NL, Friedman PJ, Hansell DM, Naidich DP, Remy-Jardin M, Webb WR, Zerhouni EA. Glossary of terms for CT of the lungs: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. Radiology 200: 327–331, 1996. doi: 10.1148/radiology.200.2.8685321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu S, Kwee TC, Surti S, Akin EA, Yoo D, Alavi A. Fundamentals of PET and PET/CT imaging. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1228: 1–18, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, Waldron JA. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 155: 242–248, 1997. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beijers RJHCG, van de Bool C, van den Borst B, Franssen FME, Wouters EFM, Schols AMWJ. Normal weight but low muscle mass and abdominally obese: implications for the cardiometabolic risk profile in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 18: 533–538, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blake GM, Naeem M, Boutros M. Comparison of effective dose to children and adults from dual X-ray absorptiometry examinations. Bone 38: 935–942, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutou AK, Zoumot Z, Nair A, Davey C, Hansell DM, Jamurtas A, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS. The impact of homogeneous versus heterogeneous emphysema on dynamic hyperinflation in patients with severe COPD assessed for lung volume reduction. COPD 12: 598–605, 2015. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2015.1020149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bucerius J, Mani V, Wong S, Moncrieff C, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Machac J, Fuster V, Farkouh ME, Rudd JH, Fayad ZA. Arterial and fat tissue inflammation are highly correlated: a prospective 18F-FDG PET/CT study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 41: 934–945, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2653-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bucerius J, Vijgen GH, Brans B, Bouvy ND, Bauwens M, Rudd JH, Havekes B, Fayad ZA, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Mottaghy FM. Impact of bariatric surgery on carotid artery inflammation and the metabolic activity in different adipose tissues. Medicine (Baltimore) 94: e725, 2015. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budd G. Remarks on emphysema of the lungs. Med Chir Trans 23: 37–62, 1840. doi: 10.1177/095952874002300105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Budoff MJ, Hamirani YS, Gao YL, Ismaeel H, Flores FR, Child J, Carson S, Nee JN, Mao S. Measurement of thoracic bone mineral density with quantitative CT. Radiology 257: 434–440, 2010. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carrière A, Jeanson Y, Berger-Müller S, André M, Chenouard V, Arnaud E, Barreau C, Walther R, Galinier A, Wdziekonski B, Villageois P, Louche K, Collas P, Moro C, Dani C, Villarroya F, Casteilla L. Browning of white adipose cells by intermediate metabolites: an adaptive mechanism to alleviate redox pressure. Diabetes 63: 3253–3265, 2014. doi: 10.2337/db13-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castaldi PJ, Cho MH, San José Estépar R, McDonald ML, Laird N, Beaty TH, Washko G, Crapo JD, Silverman EK; COPDGene Investigators . Genome-wide association identifies regulatory Loci associated with distinct local histogram emphysema patterns. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 190: 399–409, 2014. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0569OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castaldi PJ, San José Estépar R, Mendoza CS, Hersh CP, Laird N, Crapo JD, Lynch DA, Silverman EK, Washko GR. Distinct quantitative computed tomography emphysema patterns are associated with physiology and function in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 1083–1090, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201305-0873OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cypess AM, Lehman S, Williams G, Tal I, Rodman D, Goldfine AB, Kuo FC, Palmer EL, Tseng YH, Doria A, Kolodny GM, Kahn CR. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N Engl J Med 360: 1509–1517, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 379: 1341–1351, 2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz AA, Young TP, Kurugol S, Eckbo E, Muralidhar N, Chapman JK, Kinney GL, Ross JC, San Jose Estepar R, Harmouche R, Black-Shinn JL, Budoff M, Bowler RP, Hokanson J, Washko GR; COPDGene investigators . Abdominal visceral adipose tissue is associated with myocardial infarction in patients with COPD. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2: 8–16, 2015. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2.1.2014.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Zulueta J, Cabrera C, Zagaceta J, Hunninghake G, Celli B; BODE Collaborative Group . Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 155–161, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0034OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Divo MJ, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata VM, de-Torres JP, Zulueta JJ, Cabrera C, Zagaceta J, Sanchez-Salcedo P, Berto J, Davila RB, Alcaide AB, Cote C, Celli BR; BODE Collaborative Group . COPD comorbidities network. Eur Respir J 46: 640–650, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00171614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle TJ, Dellaripa PF, Batra K, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Hatabu H, Nishino M, Weinblatt ME, Ascherman DP, Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Choi AMK, Shadick NA, Rosas IO. Functional impact of a spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest 146: 41–50, 2014. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doyle TJ, Hunninghake GM, Rosas IO. Subclinical interstitial lung disease: why you should care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 1147–1153, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1420PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doyle TJ, Washko GR, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, Divo MJ, Celli BR, Sciurba FC, Silverman EK, Hatabu H, Rosas IO, Hunninghake GM; COPDGene Investigators . Interstitial lung abnormalities and reduced exercise capacity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 185: 756–762, 2012. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201109-1618OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Engelen MP, Schols AM, Does JD, Gosker HR, Deutz NE, Wouters EF. Exercise-induced lactate increase in relation to muscle substrates in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1697–1704, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9910066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Engelen MP, Schols AM, Does JD, Wouters EF. Skeletal muscle weakness is associated with wasting of extremity fat-free mass but not with airflow obstruction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 71: 733–738, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelen MP, Schols AM, Lamers RJ, Wouters EF. Different patterns of chronic tissue wasting among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Nutr 18: 275–280, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(98)80024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Estépar RS, Kinney GL, Black-Shinn JL, Bowler RP, Kindlmann GL, Ross JC, Kikinis R, Han MK, Come CE, Diaz AA, Cho MH, Hersh CP, Schroeder JD, Reilly JJ, Lynch DA, Crapo JD, Wells JM, Dransfield MT, Hokanson JE, Washko GR; COPDGene Study . Computed tomographic measures of pulmonary vascular morphology in smokers and their clinical implications. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188: 231–239, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201301-0162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fimognari FL, Scarlata S, Pastorelli R, Antonelli-Incalzi R. Visceral obesity and different phenotypes of COPD. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 192–193, 2009. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.180.2.192a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishman A, Martinez F, Naunheim K, Piantadosi S, Wise R, Ries A, Weinmann G, Wood DE; National Emphysema Treatment Trial Research Group . A randomized trial comparing lung-volume-reduction surgery with medical therapy for severe emphysema. N Engl J Med 348: 2059–2073, 2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forsberg AM, Nilsson E, Werneman J, Bergström J, Hultman E. Muscle composition in relation to age and sex. Clin Sci (Lond) 81: 249–256, 1991. doi: 10.1042/cs0810249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gifford JR, Trinity JD, Layec G, Garten RS, Park SY, Rossman MJ, Larsen S, Dela F, Richardson RS. Quadriceps exercise intolerance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the potential role of altered skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration. J Appl Physiol (1985) 119: 882–888, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00460.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Thaete FL, He J, Ross R. Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol (1985) 89: 104–110, 2000. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodsitt MM. Evaluation of a new set of calibration standards for the measurement of fat content via DPA and DXA. Med Phys 19: 35–44, 1992. doi: 10.1118/1.596890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han MK, Kazerooni EA, Lynch DA, Liu LX, Murray S, Curtis JL, Criner GJ, Kim V, Bowler RP, Hanania NA, Anzueto AR, Make BJ, Hokanson JE, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, Martinez FJ, Washko GR; COPDGene Investigators . Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in the COPDGene study: associated radiologic phenotypes. Radiology 261: 274–282, 2011. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heard BE, Khatchatourov V, Otto H, Putov NV, Sobin L. The morphology of emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and bronchiectasis: definition, nomenclature, and classification. J Clin Pathol 32: 882–892, 1979. doi: 10.1136/jcp.32.9.882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hillas G, Perlikos F, Tsiligianni I, Tzanakis N. Managing comorbidities in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 10: 95–109, 2015. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S54473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hogg JC, Macklem PT, Thurlbeck WM. Site and nature of airway obstruction in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med 278: 1355–1360, 1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196806202782501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunninghake GM, Hatabu H, Okajima Y, Gao W, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Nishino M, Araki T, Zazueta OE, Kurugol S, Ross JC, San José Estépar R, Murphy E, Steele MP, Loyd JE, Schwarz MI, Fingerlin TE, Rosas IO, Washko GR, O’Connor GT, Schwartz DA. MUC5B promoter polymorphism and interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med 368: 2192–2200, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1216076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobson G, Turner AF, Balchum OJ, Jung R. Vascular changes in pulmonary emphysema. The radiologic evaluation by selective and peripheral pulmonary wedge angiography. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 100: 374–396, 1967. doi: 10.2214/ajr.100.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jebb SA. Measurement of soft tissue composition by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry. Br J Nutr 77: 151–163, 1997. doi: 10.1079/BJN19970021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones DA, Round JM, Edwards RH, Grindwood SR, Tofts PS. Size and composition of the calf and quadriceps muscles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. A tomographic and histochemical study. J Neurol Sci 60: 307–322, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(83)90071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaul S, Rothney MP, Peters DM, Wacker WK, Davis CE, Shapiro MD, Ergun DL. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for quantification of visceral fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20: 1313–1318, 2012. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerley P. Emphysema: (section of radiology). Proc R Soc Med 29: 1307–1324, 1936. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, Boje Jensen G, Divo M, Faner R, Guerra S, Marott JL, Martinez FD, Martinez-Camblor P, Meek P, Owen CA, Petersen H, Pinto-Plata V, Schnohr P, Sood A, Soriano JB, Tesfaigzi Y, Vestbo J. Lung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 373: 111–122, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lehouck A, Boonen S, Decramer M, Janssens W. COPD, bone metabolism, and osteoporosis. Chest 139: 648–657, 2011. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leone N, Courbon D, Thomas F, Bean K, Jégo B, Leynaert B, Guize L, Zureik M. Lung function impairment and metabolic syndrome: the critical role of abdominal obesity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 509–516, 2009. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1195OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leopold JG, Gough J. The centrilobular form of hypertrophic emphysema and its relation to chronic bronchitis. Thorax 12: 219–235, 1957. doi: 10.1136/thx.12.3.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lima MM, Pareja JC, Alegre SM, Geloneze SR, Kahn SE, Astiarraga BD, Chaim EA, Baracat J, Geloneze B. Visceral fat resection in humans: effect on insulin sensitivity, beta-cell function, adipokines, and inflammatory markers. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21: E182–E189, 2013. doi: 10.1002/oby.20030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin H, Yan H, Rao S, Xia M, Zhou Q, Xu H, Rothney MP, Xia Y, Wacker WK, Ergun DL, Zeng M, Gao X. Quantification of visceral adipose tissue using lunar dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in Asian Chinese. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21: 2112–2117, 2013. doi: 10.1002/oby.20325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.López M, Varela L, Vázquez MJ, Rodríguez-Cuenca S, González CR, Velagapudi VR, Morgan DA, Schoenmakers E, Agassandian K, Lage R, Martínez de Morentin PB, Tovar S, Nogueiras R, Carling D, Lelliott C, Gallego R, Oresic M, Chatterjee K, Saha AK, Rahmouni K, Diéguez C, Vidal-Puig A. Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nat Med 16: 1001–1008, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nm.2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maddocks M, Shrikrishna D, Vitoriano S, Natanek SA, Tanner RJ, Hart N, Kemp PR, Moxham J, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS. Skeletal muscle adiposity is associated with physical activity, exercise capacity and fibre shift in COPD. Eur Respir J 44: 1188–1198, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00066414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marquis K, Debigaré R, Lacasse Y, LeBlanc P, Jobin J, Carrier G, Maltais F. Midthigh muscle cross-sectional area is a better predictor of mortality than body mass index in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 809–813, 2002. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonald ML, Diaz AA, Ross JC, San Jose Estepar R, Zhou L, Regan EA, Eckbo E, Muralidhar N, Come CE, Cho MH, Hersh CP, Lange C, Wouters E, Casaburi RH, Coxson HO, Macnee W, Rennard SI, Lomas DA, Agusti A, Celli BR, Black-Shinn JL, Kinney GL, Lutz SM, Hokanson JE, Silverman EK, Washko GR. Quantitative computed tomography measures of pectoralis muscle area and disease severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A cross-sectional study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 11: 326–334, 2014. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201307-229OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Micklesfield LK, Goedecke JH, Punyanitya M, Wilson KE, Kelly TL. Dual-energy X-ray performs as well as clinical computed tomography for the measurement of visceral fat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20: 1109–1114, 2012. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Müller NL, Staples CA, Miller RR, Abboud RT. “Density mask”. An objective method to quantitate emphysema using computed tomography. Chest 94: 782–787, 1988. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakano Y, Muro S, Sakai H, Hirai T, Chin K, Tsukino M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Paré PD, Hogg JC, Mishima M. Computed tomographic measurements of airway dimensions and emphysema in smokers. Correlation with lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1102–1108, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9907120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gastonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 365: 395–409, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Niimi A, Matsumoto H, Amitani R, Nakano Y, Mishima M, Minakuchi M, Nishimura K, Itoh H, Izumi T. Airway wall thickness in asthma assessed by computed tomography. Relation to clinical indices. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1518–1523, 2000. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9909044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Op den Kamp CM, Langen RC, Snepvangers FJ, de Theije CC, Schellekens JM, Laugs F, Dingemans AM, Schols AM. Nuclear transcription factor κ B activation and protein turnover adaptations in skeletal muscle of patients with progressive stages of lung cancer cachexia. Am J Clin Nutr 98: 738–748, 2013. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ostridge K, Williams N, Kim V, Harden S, Bourne S, Coombs NA, Elkington PT, Estepar RS, Washko G, Staples KJ, Wilkinson TM. Distinct emphysema subtypes defined by quantitative CT analysis are associated with specific pulmonary matrix metalloproteinases. Respir Res 17: 92, 2016. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0402-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park MJ, Cho JM, Jeon KN, Bae KS, Kim HC, Choi DS, Na JB, Choi HC, Choi HY, Kim JE, Shin HS. Mass and fat infiltration of intercostal muscles measured by CT histogram analysis and their correlations with COPD severity. Acad Radiol 21: 711–717, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pietrobelli A, Formica C, Wang Z, Heymsfield SB. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry body composition model: review of physical concepts. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 271: E941–E951, 1996. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.6.E941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pietrobelli A, Wang Z, Formica C, Heymsfield SB. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: fat estimation errors due to variation in soft tissue hydration. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 274: E808–E816, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.5.E808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Putman RK, Hatabu H, Araki T, Gudmundsson G, Gao W, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Dupuis J, Latourelle JC, Cho MH, El-Chemaly S, Coxson HO, Celli BR, Fernandez IE, Zazueta OE, Ross JC, Harmouche R, Estépar RS, Diaz AA, Sigurdsson S, Gudmundsson EF, Eiríksdottír G, Aspelund T, Budoff MJ, Kinney GL, Hokanson JE, Williams MC, Murchison JT, MacNee W, Hoffmann U, O’Donnell CJ, Launer LJ, Harrris TB, Gudnason V, Silverman EK, O’Connor GT, Washko GR, Rosas IO, Hunninghake GM; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators; COPDGene Investigators . Association between interstitial lung abnormalities and all-cause mortality. JAMA 315: 672–681, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reymond E, Jankowski A, Pison C, Bosson JL, Prieur M, Aniwidyaningsih W, Ferretti GR. Prediction of lobar collateral ventilation in 25 patients with severe emphysema by fissure analysis with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 201: W571–W575, 2013. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ross JC, San Jose Estepar R, Kindlmann G, Diaz A, Westin CF, Silverman EK, Washko GR. Automatic lung lobe segmentation using particles, thin plate splines, and maximum a posteriori estimation. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv 13: 163–171, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scarrow GD. The pulmonary angiogram in chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Proc R Soc Med 58: 684–687, 1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schols AM, Ferreira IM, Franssen FM, Gosker HR, Janssens W, Muscaritoli M, Pison C, Rutten-van Mölken M, Slinde F, Steiner MC, Tkacova R, Singh SJ. Nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD: a European Respiratory Society statement. Eur Respir J 44: 1504–1520, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schols AM, Fredrix EW, Soeters PB, Westerterp KR, Wouters EF. Resting energy expenditure in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 54: 983–987, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schweitzer L, Geisler C, Pourhassan M, Braun W, Glüer CC, Bosy-Westphal A, Müller MJ. What is the best reference site for a single MRI slice to assess whole-body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes in healthy adults? Am J Clin Nutr 102: 58–65, 2015. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.111203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seibold MA, Wise AL, Speer MC, Steele MP, Brown KK, Loyd JE, Fingerlin TE, Zhang W, Gudmundsson G, Groshong SD, Evans CM, Garantziotis S, Adler KB, Dickey BF, du Bois RM, Yang IV, Herron A, Kervitsky D, Talbert JL, Markin C, Park J, Crews AL, Slifer SH, Auerbach S, Roy MG, Lin J, Hennessy CE, Schwarz MI, Schwartz DA. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 364: 1503–1512, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, Gallagher D, St-Onge MP, Albu J, Heymsfield SB, Heshka S. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97: 2333–2338, 2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00744.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shrikrishna D, Patel M, Tanner RJ, Seymour JM, Connolly BA, Puthucheary ZA, Walsh SL, Bloch SA, Sidhu PS, Hart N, Kemp PR, Moxham J, Polkey MI, Hopkinson NS. Quadriceps wasting and physical inactivity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 40: 1115–1122, 2012. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sin DD, Jones RL, Man SF. Obesity is a risk factor for dyspnea but not for airflow obstruction. Arch Intern Med 162: 1477–1481, 2002. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.13.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Storbeck B, Schröder TH, Oldigs M, Rabe KF, Weber C. Emphysema: Imaging for Endoscopic Lung Volume Reduction. RoFo Fortschr Geb Rontgenstr Nuklearmed 187: 543–554, 2015. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1399424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Swallow EB, Reyes D, Hopkinson NS, Man WD, Porcher R, Cetti EJ, Moore AJ, Moxham J, Polkey MI. Quadriceps strength predicts mortality in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 62: 115–120, 2007. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.van de Bool C, Rutten EP, Franssen FM, Wouters EF, Schols AM. Antagonistic implications of sarcopenia and abdominal obesity on physical performance in COPD. Eur Respir J 46: 336–345, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00197314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van den Borst B, Gosker HR, Koster A, Yu B, Kritchevsky SB, Liu Y, Meibohm B, Rice TB, Shlipak M, Yende S, Harris TB, Schols AM; Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study . The influence of abdominal visceral fat on inflammatory pathways and mortality risk in obstructive lung disease. Am J Clin Nutr 96: 516–526, 2012. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Vanhommerig JW, Smulders NM, Drossaerts JM, Kemerink GJ, Bouvy ND, Schrauwen P, Teule GJ. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue in healthy men. N Engl J Med 360: 1500–1508, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Van Tho N, Ogawa E, Trang TH, Ryujin Y, Kanda R, Nakagawa H, Goto K, Fukunaga K, Higami Y, Seto R, Wada H, Yamaguchi M, Nagao T, Lan TT, Nakano Y. A mixed phenotype of airway wall thickening and emphysema is associated with dyspnea and hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12: 988–996, 2015. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201411-501OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, Gaffron S, van Empel VP, Bruijnzeel PL, Rutten EP, Op ’t Roodt J, Wouters EF, Franssen FM. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187: 728–735, 2013. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1665OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vanfleteren LE, van Meerendonk AM, Franssen FM, Wouters EF, Mottaghy FM, van Kroonenburgh MJ, Bucerius J. A possible link between increased metabolic activity of fat tissue and aortic wall inflammation in subjects with COPD. A retrospective 18F-FDG-PET/CT pilot study. Respir Med 108: 883–890, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Q, Zhang M, Ning G, Gu W, Su T, Xu M, Li B, Wang W. Brown adipose tissue in humans is activated by elevated plasma catecholamines levels and is inversely related to central obesity. PLoS One 6: e21006, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Washko GR, Hunninghake GM, Fernandez IE, Nishino M, Okajima Y, Yamashiro T, Ross JC, Estépar RS, Lynch DA, Brehm JM, Andriole KP, Diaz AA, Khorasani R, D’Aco K, Sciurba FC, Silverman EK, Hatabu H, Rosas IO; COPDGene Investigators . Lung volumes and emphysema in smokers with interstitial lung abnormalities. N Engl J Med 364: 897–906, 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Washko GR, Lynch DA, Matsuoka S, Ross JC, Umeoka S, Diaz A, Sciurba FC, Hunninghake GM, San José Estépar R, Silverman EK, Rosas IO, Hatabu H. Identification of early interstitial lung disease in smokers from the COPDGene Study. Acad Radiol 17: 48–53, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wells JM, Iyer AS, Rahaghi FN, Bhatt SP, Gupta H, Denney TS, Lloyd SG, Dell’Italia LJ, Nath H, Estepar RS, Washko GR, Dransfield MT. Pulmonary artery enlargement is associated with right ventricular dysfunction and loss of blood volume in small pulmonary vessels in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 8: e002546, 2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wells JM, Washko GR, Han MK, Abbas N, Nath H, Mamary AJ, Regan E, Bailey WC, Martinez FJ, Westfall E, Beaty TH, Curran-Everett D, Curtis JL, Hokanson JE, Lynch DA, Make BJ, Crapo JD, Silverman EK, Bowler RP, Dransfield MT; COPDGene Investigators; ECLIPSE Study Investigators . Pulmonary arterial enlargement and acute exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 367: 913–921, 2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Williams MC, Murchison JT, Edwards LD, Agustí A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, Lomas DA, Miller BE, Rennard S, Silverman EK, Tal-Singer R, Vestbo J, Wouters E, Yates JC, van Beek EJ, Newby DE, MacNee W; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) investigators . Coronary artery calcification is increased in patients with COPD and associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Thorax 69: 718–723, 2014. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yue L, Yao H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in inflammatory responses and cellular senescence: pathogenesis and pharmacological targets for chronic lung diseases. Br J Pharmacol 173: 2305–2318, 2016. doi: 10.1111/bph.13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]