Abstract

Ultra-compact micro-optical elements for endoscopic instruments and miniaturized microscopes allow for non-invasive and non-destructive examination of microstructures and tissues. With sub-cellular level resolution such instruments could provide immediate diagnosis that is virtually consistent with a histologic diagnosis enabling for example to differentiate the boundaries between malignant and benign tissue. Such instruments are now being developed at a rapid rate; however, current manufacturing technologies limit the instruments to very large sizes, well beyond the sub-mm sizes required in order to ensure minimal tissue damage. We show here a platform based on planar microfabrication and soft lithography that overcomes the limitation of current optical elements enabling single cell resolution. We show the ability to resolve lithographic features that are as small as 2 μm using probes with a cross section that is only 100 microns in size. We also show the ability to image individual activated neural cells in brain slices via our fabricated probe.

Introduction

The size of endoscopic instruments with high resolution at the sub-cellular level, is limited by the current micro-optical elements, which in turn are constrained to large sizes due to their manufacturing process. Optical fiber bundles1,2, miniaturized lenses2,3, and gradient index (GRIN) lenses4 have been applied for endoscopic imaging. Optical fiber bundles have been utilized for epifluorescence in vivo calcium imaging5, confocal imaging6, and two photon imaging7. However, they suffer from lack of resolution, determined by size of the fiber6. Miniaturized lenses have been applied for endomicroscopes2, and confocal imaging8. However, since miniaturized lenses are achieved via micromanipulation and polishing9, their size is usually limited to millimeter scale. GRIN lenses have been utilized to image brain tissue using single10–13 or two-photon13 imaging techniques. However, they have a typical diameter of approximately 0.5–1 mm. These lenses have successfully been utilized for optical coherence tomography imaging of a coronary artery14 and esophagus15. In neuroscience studies, GRIN lenses have successfully imaged deep layers of the brain10 and have enabled the study of deep brain areas including hippocampal CA1 for memory encoding16 and hypothalamic network for appetitive behaviors17. However, GRIN lenses suffer from resolution and cross sectional area tradeoff. This tradeoff is fundamental and originates from the difficulty of forming the necessary strong gradient of the refractive index (determined by the glass doping concentration) within a small cross sectional area. Due to the difficulty in achieving such a gradient, in order to ensure focusing, these GRIN lenses typically have large cross-sectional dimensions, between 0.5 mm and 1 mm in diameter.

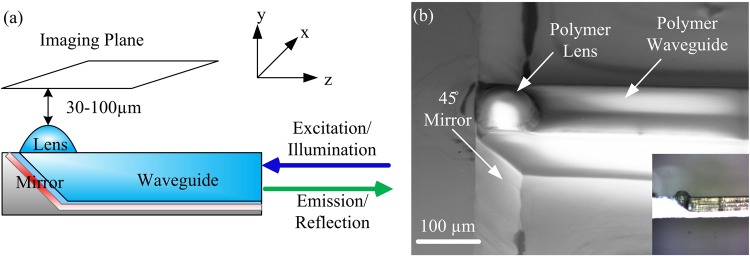

We show here a platform based on planar microfabrication that overcomes the limitation of current optical elements enabling single cell resolution using probes with a cross section that is only 100 microns in size. The probe consists of a polymeric waveguide monolithically integrated with a high Numerical Aperture (NA) microlens composed of a polymer molded into a semi-sphere (Fig. 1a). These lenses are shaped using lithographic processes. Since the lensing effect in these micro-lenses is based on the shape and refractive index of the lens, they can have a diameter that is only tens of microns. This new micro-fabricated probe technology enables one to achieve high resolution (i.e. high NA) while keeping the cross section of the probe small, between 500 microns and down to only a few microns in diameter. This is in contrast to the traditional GRIN lens with a large millimeter size cross section.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the probe consisting of a polymeric waveguide, aluminum mirror and polymeric micro-lens. (b) SEM image of a fabricated probe with 80 μm × 100 μm in cross section integrated with a micro-lens with an approximate curvature radius of 45 µm; Inset shows a microscope image of the probe with the substrate thinned down to less than 50 µm.

Methods

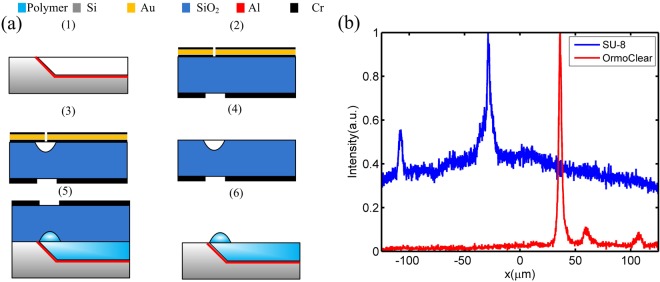

The platform leverages standard silicon manufacturing for massive scale manufacturing and relies on soft lithography for the fabrication of 3D photonic structures. (Fig. 2a). The probe substrate is defined using wet etching of silicon (Fig. 2a, step 1) utilizing a silicon dioxide hard-mask patterned with a 45° angle with respect to the silicon substrate edge18,19. Aluminum layer acting as a mirror is deposited on the silicon substrate. The lens mold on a fused silica substrate is fabricated using circular patterns defined by a mask20,21 and wet etching using a HF:DI solution to form the semi-spheres concave surfaces (Fig. 2a, steps 2–4). The mold is aligned to the silicon substrate and OrmoClear®FX (micro resist technology GmbH) is flown into the waveguide mask-and-lens mold by decreasing its viscosity and using capillary forces via careful temperature control of the substrate (Fig. 2a, step 5). The final step consists of exposing the probe to UV light for patterning and curing the polymer and, finally, releasing the probe (Fig. 2a, step 6). Following the fabrication of the probe the back side of the silicon substrate can be etched down to a few tens of microns using reactive ion etching (Fig. 1b inset). The SEM image of the resulting structure is shown in Fig. 1b. More details on the fabrication process can be found in Supplementary 1.

Figure 2.

(a) Fabrication process of the probe. (b) Fluorescence imaging of a single 6 μm fluorescent bead (with peak emission at 520 nm), via a probe fabricated using low absorption polymer Ormoclear®FX and for comparison via a probe fabricated using SU8. Both of these image profiles were taken using a 50× objective with an NA of 0.55 and a monochromatic scientific CMOS camera. The images are normalized to their respective peak intensities. One can see that the SNR level for the low absorption polymer is much higher due to its low background fluorescent emission.

The unique microfabrication methods of our process, in contrast to traditional manufacturing processes, enables one to tailor the resolution of the probe, while enabling millimeters long probes. The resolution can be tailored by designing the shape of the lens, defined by the etching time and the mask shape used in the fabrication of the lens mold22,23. The length of the probe l is given by: l = 2nfw/D, where D, w, n, f, are the field of view diameter, waveguide width, waveguide refractive index, focal distance, respectively. Assuming w = 100 μm, D = 50 μm, n = 1.56, and f = 800 μm, a probe can be several millimeters long and still maintain cellular resolution (more details presented in Supplementary 4).

In order to overcome the auto-fluorescence which has limited polymer photonics for fluorescence imaging, we minimize the energy transfer from the excitation light source to the polymer by engineering a hybrid polymer based device with ultra-low absorption in the whole visible range24. We use Ormoclear®FX – a polymer developed by micro-resist GMBH with an absorption of less than 1% between 350 nm and 800 nm. We show the ability to image a single fluorescent bead with high signal to noise ratio (SNR) overcoming the traditional source of noise due to the high auto-fluorescence in polymers25. Figure 2a shows the fluorescence imaging of a single 6 μm fluorescent bead (with peak emission at 520 nm), via a probe fabricated using low absorption polymer Ormoclear®FX and, for comparison, via a probe fabricated using SU8. SU8 is one of the standard polymer for fabrication of the polymer waveguides. Both of these profiles were taken using a 50× objective with an NA of 0.55 (Mitutoyo M Plan Apo 50×) and a monochromatic Scientific CMOS camera (ORCA flash 4.0 LT Hamamatsu Photonics). One can see that the SNR level for the low absorption polymer is much higher due to its low background fluorescent emission.

Results

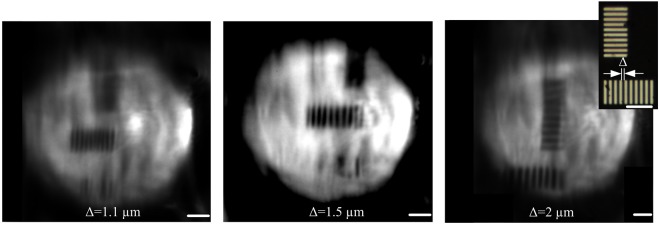

We show the ability of the probe to resolve lithographic features that are as small as 2 μm consistent with our theoretical predictions based on the measured profile of the lens and the calculation of the aberration. In order to determine the resolution of the probe, we imaged lithographically defined metallic lines spaced by Δ which varies between 1.1 μm and 2 μm μm through a fabricated probe. The probe used was 80 μm × 100 μm in cross section and was integrated with a micro-lens with an approximate curvature radius of 45 µm. The entire probe structure was fabricated using a polymer with an index of 1.56. The metallic lines were defined using electron beam lithographic patterning of an aluminum film deposited on a fused silica substrate. White light is sent through the probe for illumination and the reflected light off the object through the probe is then collected through a 50× objective with a NA of 0.55 and imaged onto a scientific CMOS camera. The working distance between the object and the lens is about 100 μm. We measure a lateral resolution of 1.1 µm along one direction and less than 2 µm along its perpendicular direction (see Fig. 3). The difference in resolution between the lateral and axial axis is due to the difference in the waveguide geometry with 80 µm thickness and 100 µm width. We performed most of the experiments in air but device can be immersed in the water as well.

Figure 3.

Images of lithographically defined metallic lines spaced by Δ which varies between 1.1 μm and 2 μm through a fabricated probe. The probe used was 80 μm × 100 μm in cross section, was integrated with a micro-lens with an approximate radius of curvature of 45 µm and was fabricated using a polymer with an index of 1.56. We measure a lateral resolution of 1.1 µm along one direction and less than 2 µm along its perpendicular direction. All the scale bars are 10 μm.

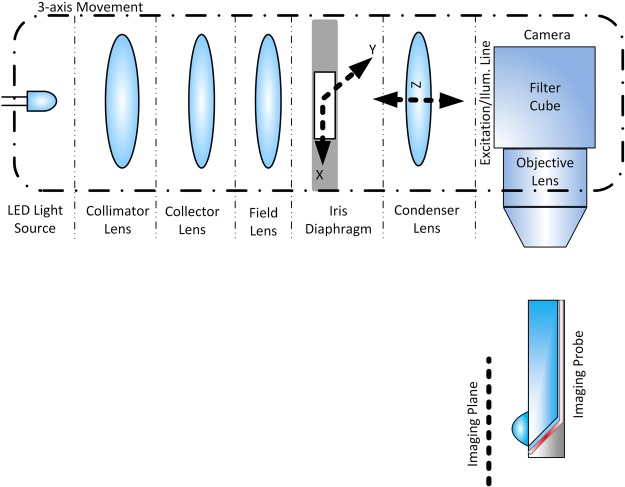

The imaging set-up shown in Fig. 4 has been utilized to characterize the probe. To illuminate the imaging target and reconstruct the image formed behind the lens, we use the free space imaging set-up located behind the waveguide. This setup can be replaced with any reflected light microscopy system. We use the Köhler illumination method for the illumination part of the imaging setup. For the case of the reflected light microscopy, this type of illumination provided a better contrast. The image replica of the iris diaphragm is on the image plane of the imaging setup. This is used to make the illuminating area as small as the waveguide area. The optimization of the illumination line helps to improve the contrast in the image, but a good quality image can be achieved even without optimization of the illumination line. We utilized a 50× objective with an NA of 0.55 (Mitutoyo M Plan Apo 50×) and a monochromatic Scientific CMOS camera (ORCA flash 4.0 LT Hamamatsu Photonics) for all of the imaging. For more details on the measurement set-up please see Supplementary 2.

Figure 4.

Optical imaging setup for illumination and imaging from the endoscopic probe.

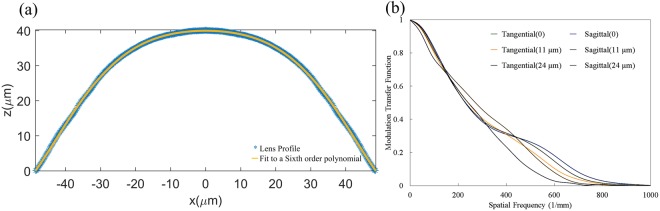

We quantify the monochromatic aberrations of the lens defined by the lens shape and show that although the lens shape induces some aberrations, the resolution remains well within the range necessary for imaging individual cells. In Fig. 5a, we show the lens profile extracted from the lens mold profile and the fit to a sixth order polynomial. Using this fit, we calculate the modulation transfer function (MTF) diagram at the focal plane of the lens for a wavelength of 550 nm across the lens field of view, using OpticStudio (Zemax, LLC) (see Fig. 5b). One can see from the MTF of the lens that the expected resolution of our probe is in agreement with our experimental imaging results. The cut-off resolution of the probe is about 730 lp/mm and the resolution of the probe based on the Rayleigh criterion (Airy disk radius) is 1.3–1.4 μm. Note that, in principle, using multi-lenses these aberrations could be alleviated in the future using the method presented in26,27.

Figure 5.

(a) The fabricated lens profile. Dots are extracted from the microscope image and solid line is a fit to a fourth order polynomial. (b) Calculated Modulated Transfer Function at the lens focal plane for a wavelength of 550 nm using the approximated fit profile at the focal plane of the lens using OpticStudio (Zemax LLC). One can see from the MTF of the lens that the cut-off resolution of our probe is about 700 lp/mm is in agreement with our experimental imaging results.

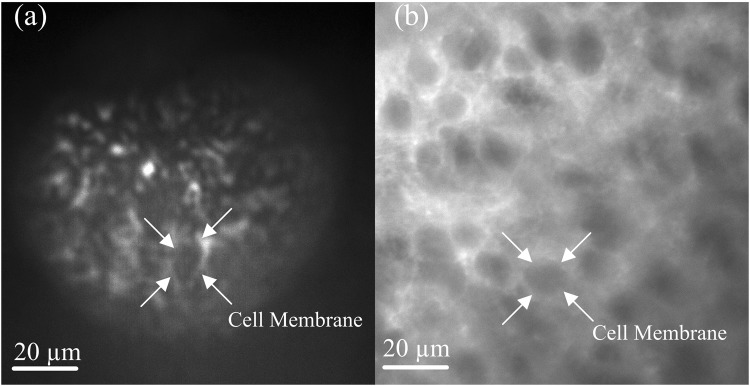

As an example of an application of our platform, we show cellular level resolution by imaging activated neural cells in brain slices using wide-field microscopy via our fabricated probe. Wide field microscopy has been used for imaging neural dynamics in various brain structures27,28. Unlike conventional two-photon microscopy, in wide-field microscopy all pixels in an image are sampled simultaneously. Therefore, this method is advantageous over two-photon microscopy for high speed functional imaging. Figure 6a shows images of slices taken from the cerebral cortex region of an ArcCreERT229 x ChR2- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)30 transgenic mouse obtained using the fabricated microprobe. This mouse line offers permanent membrane bound EYFP labeling of Arc+ neurons, which were activated during the learning experience29. The captured image shown in Fig. 6a clearly shows differentiated neuron boundaries with a FOV of 65 μm. More details on the preparation of slices can be found in Supplementary 3. For comparison we also show in Fig. 6b the image collected using a typical image of the cerebral cortex using the regular microscope (standard bench top microscope). Note that due to the tagging used here, only the cell membranes fluoresce while the encapsulated cells within the membranes appear darker in the image.

Figure 6.

Wide-field microscopy of activated neural cells in brain slices of activated neural cells taken from the cerebral cortex region of an ArcCreERT234 x ChR2- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)29 transgenic mouse28. This mouse line offers permanent membrane bound EYFP labeling of Arc+ neurons, which were activated during the learning of an experience34. (a) The image obtained using the fabricated microprobe the captured image shown shows differentiated neuron boundaries with a FOV of 65 μm. (b) The image collected using a standard bench top microscope.

The same probe has been inserted in the mouse left visual cortex for optogenetic excitation of neurons and the insertion damage to the tissue can be seen in31. The probe can be inserted either with a thinned substrate or as a standalone polymeric lens waveguide. The polymeric waveguide-lens probe can be released from the substrate and inserted. The insertion force of the 100 μm flat probe to the brain cortex is about 0.5–0.6 mN32. The critical force for the buckling of the probe based on the Euler’s buckling equation is, Fcritical = Kπ2 EI/L2, where K, E, I, and L are column effective length factor, modulus of elasticity, area moment of inertia, and length of the probe respectively33. Considering Fixed-Pinned or Fixed-Fixed boundary conditions (K = 2–4)33, modulus of elasticity of the polymer (E = 4 GPa), the probe length of 5 mm, and cross sectional area of 100 μm × 100 μm, critical force to buckle the probe is 25–50 mN. Therefore, the buckling force of the standalone polymeric probe is significantly larger than the insertion force to the brain cortex.

Conclusion

The demonstrated platform allows for a completely new generation of microprobes to be used in imaging for a variety of applications. In neuroscience, this can enable the implementation of multiple techniques (such as wide field microscopy and multi-photon imaging) used today for imaging and excitation of deep brain tissues and, in contrast to the GRIN lenses used today, can be minimally invasive. In medical engineering, it could enable emerging applications that require cellular level resolution for diagnostics involving multiple modalities techniques emerging today such as optical coherence tomography, fluorescence (auto-fluorescence or via an injected dye) imaging, and spectroscopy of the cells. Most of these techniques are being introduced in endoscopic instruments that are several mm wide and, therefore, limited to applications such as colon studies where such large endoscopic tools can be inserted. For example, OCT can be used for confirming clear margins in cancer removal procedures and minimally invasive imaging for replacing biopsies. Note that although we have shown here a side imaging probe, using the same fabrication technique (based on aligning micro fabricated molds) one can realize a forward imaging probe with multiple embedded lenses in order to ensure minimal aberrations and maximize the field of view for a probe length of several millimeters long.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. IOS-1611090 and the Columbia University Office of the Executive Vice President Research Initiatives in Science & Engineering (RISE). This work was performed in part at the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the Cornell NanoScale Science & Technology Facility at the Cornell University.

Author Contributions

M.A.T., M.L. designed the probe, I.P., K.M.M., C.A.D. designed and prepared the slices, M.A.T. fabricated the probe, A.M. thinned the probe, M.A.T., S.P.R. designed and fabricated the imaging target, M.A.T. did the experiments, A.M., F.B. did the mirror characterization, M.A.T., M.L., I.P., K.M.M. and C.A.D. prepared the manuscript, M.L., M.A.T., A.M. and C.A.D. revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29090-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Flusberg BA, et al. Fiber-optic fluorescence imaging. Nature methods. 2005;2(12):941. doi: 10.1038/nmeth820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlson K, et al. In vivo fiber-optic confocal reflectance microscope with an injection-molded plastic miniature objective lens. Applied optics. 2005;44(10):1792–1797. doi: 10.1364/AO.44.001792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabatabaei N, et al. Clinical Translation of Tethered Confocal Microscopy Capsule for Unsedated Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Scientific reports. 2018;8(1):2631. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20668-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knittel J, Schnieder L, Buess G, Messerschmidt B, Possner T. Endoscope-compatible confocal microscope using a gradient index-lens system. Optics Communications. 2001;188(5–6):267–273. doi: 10.1016/S0030-4018(00)01164-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano M, Yamashita Y, Miyakawa A. In vivo visualization of hippocampal cells and dynamics of Ca2+ concentration during anoxia: feasibility of a fiber-optic plate microscope system for in vivo experiments. Brain research. 1996;732(1–2):61–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouse AR, Gmitro AF. Multispectral imaging with a confocal microendoscope. Optics letters. 2000;25(23):1708–1710. doi: 10.1364/OL.25.001708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Göbel W, Kerr JN, Nimmerjahn A, Helmchen F. Miniaturized two-photon microscope based on a flexible coherent fiber bundle and a gradient-index lens objective. Optics letters. 2004;29(21):2521–2523. doi: 10.1364/OL.29.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alter, P. et al An Introduction to Fiber Optic Imaging. www.us.schott.com/fiberoptics, Second Edition (2007).

- 9.Gobron, S. & Rovani, W. U.S. Patent Application No. 10/056,694 (2002).

- 10.Jung JC, Mehta AD, Aksay E, Stepnoski R, Schnitzer MJ. In vivo mammalian brain imaging using one-and two-photon fluorescence microendoscopy. J. of neurophysiology. 2004;92(5):3121–3133. doi: 10.1152/jn.00234.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh G, Chung E, Yun SH. Optical fibers for high-resolution in vivo microendoscopic fluorescence imaging. Optical Fiber Technology. 2013;19(6):760–771. doi: 10.1016/j.yofte.2013.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barretto RP, Messerschmidt B, Schnitzer MJ. In vivo fluorescence imaging with high-resolution microlenses. Nature methods. 2009;6(7):511–512. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung JC, Schnitzer MJ. Multiphoton endoscopy. Optics letters. 2003;28(11):902–904. doi: 10.1364/OL.28.000902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujimoto JG. Optical coherence tomography for ultrahigh resolution in vivo imaging. Nature biotechnology. 2003;21(11):1361–1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li XD, et al. Optical coherence tomography: advanced technology for the endoscopic imaging of Barrett’s esophagus. Endoscopy. 2000;32(12):921–930. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Resendez SL, et al. Visualization of cortical, subcortical and deep brain neural circuit dynamics during naturalistic mammalian behavior with head-mounted microscopes and chronically implanted lenses. Nature protocols. 2016;11(3):566–597. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai DJ, et al. A shared neural ensemble links distinct contextual memories encoded close in time. Nature. 2016;534(7605):115. doi: 10.1038/nature17955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnik D, Vrtacnik D, Aljancic U, Mozek M, Amon S. The role of Triton surfactant in anisotropic etching of {1 1 0} reflective planes on (1 0 0)silicon. J. of Micromechanics and Microengineering. 2005;15(6):1174. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/15/6/007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rola KP, Ptasiński K, Zakrzewski A, Zubel I. Silicon 45 micromirrors fabricated by etching in alkaline solutions with organic additives. Microsystem Technologies. 2014;20(2):221–226. doi: 10.1007/s00542-013-1859-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang P, et al. Microlens fabrication using an etched glass master. Microsystem technologies. 2007;13(3–4):339–342. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosse A, Grewe M, Fouckhardt H. Deep wet etching of fused silica glass for hollow capillary optical leaky waveguides in microfluidic devices. J. of micromechanics and microengineering. 2001;11(3):257. doi: 10.1088/0960-1317/11/3/315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tvingstedt K, Dal Zilio S, Inganäs O, Tormen M. Trapping light with micro lenses in thin film organic photovoltaic cells. Optics Express. 2008;16(26):21608–21615. doi: 10.1364/OE.16.021608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tormen M, Carpentiero A, Ferrari E, Cojoc D, Di Fabrizio E. Novel fabrication method for three-dimensional nanostructuring: an application to micro-optics. Nanotechnology. 2007;18(38):385301. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/38/385301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sikanen T, et al. Hybrid ceramic polymers: New, nonbiofouling, and optically transparent materials for microfluidics. Analytical chemistry. 2010;82(9):3874–3882. doi: 10.1021/ac1004053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamai H, et al. Development of low-fluorescence thick photoresist for high-aspect-ratio microstructure in bio-application. Biomicrofluidics. 2015;9(2):022405. doi: 10.1063/1.4917511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gissibl T, Thiele S, Herkommer A, Giessen H. Two-photon direct laser writing of ultracompact multi-lens objectives. Nature Photonics. 2016;10(8):554–560. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2016.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiele S, Arzenbacher K, Gissibl T, Giessen H, Herkommer AM. 3D-printed eagle eye: Compound microlens system for foveated imaging. Science Advances. 2017;3(2):e1602655. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1602655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giovannucci, A. et al. Cerebellar granule cells acquire a widespread predictive feedback signal during motor learning. Nature Neuroscience (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Denny CA, et al. Hippocampal memory traces are differentially modulated by experience, time, and adult neurogenesis. Neuron. 2014;83(1):189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madisen L, et al. A toolbox of Cre-dependent optogenetic transgenic mice for light-induced activation and silencing. Nature neuroscience. 2012;15(5):793–802. doi: 10.1038/nn.3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tadayon, M. A. et al. Integrated nanophotonic platform for high bandwidth and high resolution optogenetic excitation. Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics (CLEO), ATu4O 4 (2016, June) (2016).

- 32.Sharp AA, Ortega AM, Restrepo D, Curran-Everett D, Gall K. In vivo penetration mechanics and mechanical properties of mouse brain tissue at micrometer scales. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 2009;56(1):45–53. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2008.2003261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fain R, Barbosa F, Cardenas J, Lipson M. Photonic Needles for Light Delivery in Deep Tissue-like Media. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):5627. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05746-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh KK, et al. Miniaturized integration of a fluorescence microscope. Nature methods. 2011;8(10):871–878. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.