Abstract

This cross-sectional study aims to examine the associations between engagement in cognitive, social, and religious activity and cognitive function (i.e., global cognition, cognitive performance, episodic memory, working memory, and executive function) and to explore the moderation effect of acculturation on the associations. Data were drawn from the Population-Based Study of Chinese Elderly (PINE) Wave I. Multivariate regression analyses showed that participation in more cognitive and social activities were associated with better cognitive function indicated by all five measures. Also, more frequent attendance in religious services is related to better working memory only. Compared with those more acculturated peers, the less acculturated community-dwelling Chinese older adults benefited more from high levels of activity engagement, especially in global cognition, cognitive performance, and episodic memory. Findings illustrate the importance of increasing older adults’ exposure to cognitively stimulating and socially integrated activities or environments, which may help to preserve the cognitive function of older adults.

Keywords: cognitive function, activity engagement, acculturation, PINE

Introduction

Dementia is an important and growing individual and public health concern due to high prevalence rate and high burden to patients, family, and society (Kuiper et al., 2015). Cognitive function usually declines with aging, especially after age 70 (Aartsen, Smits, van Tilburg, Knipscheer, & Deeg, 2002). However, it is still possible to maintain or even improve cognitive functioning among some older adults (e.g., Korten et al., 1997). There has been increasing evidence that engagement in social, physical, and cognitive activity in older age may protect against dementia, even after controlling for potentially confounding variables, such as age, education, medical conditions, and apolipoprotein E genotype (Anderson et al., 2014; Fratiglioni, Paillard-Borg, & Winblad, 2004).

Activity engagement, that is, involvement in various types of activity, is central in the health of an aging society, and the physical and mental health benefits for older adults have been well established (e.g., Bath & Deeg, 2005; Morrow-Howell & Gehlert, 2012). There is emerging evidence that social activities are associated with cognition across the life course, especially in aging adults (Fratiglioni et al., 2004; James, Wilson, Barnes, & Bennett, 2011), while findings are mixed regarding the types of activity in relation to cognitive function domains (Bourassa, Memel, Woolverton, & Sbarra, 2017; Brown et al., 2012; Glei et al., 2005; McGue & Christensen, 2007). For example, Bourassa et al. (2017) found that overall participation in social activities was associated with better function and slower declines in both memory and executive function. Brown et al. (2012) documented that higher social activity levels was related to higher memory scores, and increase in social activity was only related to better performance on verbal fluency. This is probably due to the lack of consensus on social activity. The mixed results in previous research warrant further conceptualization of activity engagement and investigation of its associations with cognitive function domains, especially in immigrant aging populations. Particularly, Hispanic paradox, that is, Hispanics’ favorable health and mortality profiles relative to the non-Hispanic White population (Markides & Eschbach, 2005), calls attention to the acculturation hypothesis, which proposes cultural orientation linked to ethnicity and the effects on health (Abraído-Lanza, Chao, & Florez, 2005).

Using the first population-based epidemiologic study of U.S. Chinese older adults, Dong et al. (2014) found that watching TV, reading, and visiting community centers were most common activities and that sociodemographic factors, such as age, gender, education, marital status, and living arrangements, were associated with activity engagement. Yet, little is known regarding the impact of activity engagement on cognitive function among old Chinese Americans. A recent study found that they likely experienced declines in multiple cognitive abilities over a 2-year observation period (Li, Ding, Wu, & Dong, 2017). Given the potentially protective effects of activity engagement against age-related cognitive decline in the general older population, it is important to investigate whether engagement in cognitive activity (of information process) and social activity (of interaction with people) is related to cognitive function. And the moderation effect of acculturation needs to be considered when we examine the activity-cognition relationships in the U.S. Chinese aging population.

Older adult immigrants may face limited activity opportunities due to the risk of social isolation, limited access to socioeconomic resources as well as language barriers and cultural differences. Older Chinese immigrants have in particular experienced great difficulty in the acculturation process (Mui & Kang, 2006), and recent immigrants are at specific risk for mental illnesses (Dong, Bergren, & Chang, 2015; Mui, 1996). Acculturation may facilitate immigrants in activity engagement, especially in physical activity (Evenson, Sarmiento, & Ayala, 2004). And low acculturation poses difficulty in engagement in various leisure activities, especially among older Asian immigrants (Kim, Dattilo, & Heo, 2011). While less acculturated older adult immigrants may experience limited opportunities for social engagement, activity engagement can greatly benefit their psychological well-being (Jang & Chiriboga, 2011). It seems that expanding opportunities for social activities and community involvement is especially important for older adult immigrants to maintain their cognitive function and overall well-being.

In line with the activity theory of aging that views active engagement as an integral part of later life and an important means of promoting older adults’ well-being (Havighurst, 1961), it is hypothesized that (a) higher levels of engagement in social, cognitive, and religious activity are associated with better global, executive, episodic memory, and working memory function in the community-dwelling U.S. Chinese aging population. And acculturation affects health behaviors and outcomes as a coping strategy of living in a new cultural context (Abraído-Lanza, Armbrister, Flórez, & Aguirre, 2006), indicating its potential moderating effect in the activity-cognition relationships. Thus, it is hypothesized that (b) the positive relationships between activity engagement and cognitive function are stronger for those with lower levels of acculturation as compared with those more acculturated peers. In other words, activity engagement may serve as the alternative coping resource to compensate for the lack of acculturation related resources for the less acculturated.

Method

Sample

Data were drawn from the Population Study of Chinese Elderly (PINE) Wave I, which was conducted from 2011 to 2013, with interviews of 3,159 Chinese adults aged 60 and older. Those younger than 60, non-community-dwelling adults, or those who did not identify themselves as Chinese were excluded. Detailed descriptions of the data collection procedures have been published elsewhere (e.g., Dong, Wong, & Simon, 2014). Less than 3% of the observations has missing values, except working memory with 19% missing data. The regression analysis sample sizes ranged from 2,521 to 3,057.

Measures

Cognitive function

A battery of five instruments were used to measure cognitive performance, episodic memory, working memory, and executive function. The 30-item C-Mini-Mental State Examination (C-MMSE) was used to measure cognitive performance, based on the MMSE which has been widely used in epidemiological studies (Folstein, Anthony, Parhad, Duffy, & Gruenberg, 1985; Fried et al., 1991). The C-MMSE scale has been validated in Chinese aging populations with good reliability and validity (Chiu, Lee, Chung, & Kwong, 1994). Episodic memory was assessed using summary scores of the East Boston Memory Test-Immediate Recall (EBMT) and the East Boston Memory Test-Delayed Recall (EBDR) of brief stories (Albert et al., 1991). Working memory was assessed using the Digit Span Backwards assessment, which was drawn from the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Test (Wechsler, 1987). Executive function was assessed using the oral version of the 11-item Symbol Digit Modalities Test (Smith, 1984), which calls for rapid perceptual comparisons of numbers and symbols during the 90-s duration of the test. Finally, a global cognition score was calculated by averaging z scores of all five tests to minimize floor and ceiling artifacts and other measurement errors (Chang & Dong, 2014; Li et al., 2017).

Activity engagement

It includes participation in cognitive, social, and religious activities. Cognitive activity engagement was a composite of items including watching TV, listening to radio, reading books, reading magazines, reading newspapers, playing games, playing mahjong, and time spending on reading. Responses were rated on 5-point scales (range: 0-28; Cronbach’s α = .60). A composite of social activity engagement included going out; visiting friends; inviting guests for dinner or party; going on trips; attending concert, play, or musical; visiting museum; visiting library; and visiting community center. Responses were rated on 5-point scales (range: 0-25; Cronbach’s α = .66). Religious activity was measured by the frequency of attending organized religious services, recoded from 0 (never) to 4 (almost daily). A summary score of 16 activities was calculated (Cronbach’s α = .71), and higher scores indicated higher levels of activity engagement (range: 0-53).

Acculturation

It was measured with 12 items that had been tested and validated in minority populations (Dong et al., 2015). Each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert-type scale, asking about the proficiency and preference for speaking Chinese and/or English, use and preference of Chinese and/or English media such as TV, and preferred ethnicity of those with whom the participant interacted (range: 12-60; Cronbach’s α = .88). The interaction terms between acculturation and cognitive, social, religious, and overall activity engagement were created and tested, respectively, in the multivariate regression analyses.

Control variables

Demographics included age in years (range: 59-105), female (1), education (years of schooling, range: 0-26), personal income (range: 1 = less than US$5,000 to 10 = US$45,000 or more), years living in the United States (range: 0.1-90), number of household members (range: 0-10), and married status (1). In addition, health variables of mobility and chronic condition were included in the analyses. Mobility was an index (Rosow & Breslau, 1966), with three items measuring the help needed to do heavy housework, to walk up and downstairs, and to walk half a mile (Cronbach’s α = .80). Index of chronic conditions was a summary score of medical conditions (i.e., heart disease, stroke or brain hemorrhage, cancer, high cholesterol, diabetes, high blood pressure, a broken or fractured hip, thyroid disease, osteoarthritis, inflammation, or problems with joints) that had been diagnosed by health care providers.

Data Analysis

Bivariate analysis was first conducted to check for the presence of multicollinearity. Then multivariate regression analyses were used to estimate the associations of activity engagement and acculturation with five variables of cognitive function, respectively. Four interaction terms (acculturation with cognitive, social, religious, and total activity) were entered one by one in the analyses after controlling for activity engagement, acculturation, and covariate variables. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the sample and correlation coefficients among study variables. Results showed the absence of multicollinearity among independent variables, with correlation coefficients ranging from .01 to .50. Five dependent variables of cognitive function were highly correlated, with coefficients ranging from .45 to .94.

Table 1.

Descriptive and Bivariate Analysis Results of Study Variables.

| Correlation coefficient |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M(SD) or % | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| 1 | 72.81(8.31) | –.01 | −.11 | .05 | .35 | −.35 | −.32 | .44 | .24 | −.12 | –.02 | −.17 | .05 | −.33 | −.29 | −.23 | −.35 | −.31 |

| 2 | 57.97% | 1 | −.20 | .05 | .05 | −.12 | −.34 | .12 | .13 | −.05 | −.17 | −.07 | .14 | −.14 | −.07 | −.19 | −.13 | −.13 |

| 3 | 8.72(5.05) | 1 | .01 | −.10 | .02 | .22 | −.12 | .02 | .41 | .50 | .36 | .22 | .59 | .47 | .50 | .55 | .55 | |

| 4 | 1.95(1.14) | 1 | .35 | −.15 | −.10 | .02 | .04 | .14 | .04 | .02 | .04 | .05 | .05 | .02 | .04 | .07 | ||

| 5 | 20.02(13.18) | 1 | −.31 | −.22 | .19 | .18 | .13 | .03 | −.07 | .03 | −.12 | −.10 | −.10 | −.13 | −.09 | |||

| 6 | 1.87(1.89) | 1 | .39 | −.20 | −.14 | –.02 | −.08 | –.03 | −.10 | .07 | .07 | .03 | .07 | .06 | ||||

| 7 | 70.94% | 1 | −.24 | −.13 | .08 | .10 | .06 | −.10 | .23 | .19 | .20 | .22 | .23 | |||||

| 8 | 0.72(1.05) | 1 | .26 | −.11 | −.11 | −.21 | –.01 | −.28 | −.24 | −.24 | −.32 | −.28 | ||||||

| 9 | 2.06(1.46) | 1 | .02 | .05 | –.02 | .05 | −.06 | −.05 | −.04 | −.08 | −.06 | |||||||

| 10 | 15.25(5.12) | 1 | .33 | .26 | .20 | .37 | .32 | .27 | .34 | .34 | ||||||||

| 11 | 9.88(4.83) | 1 | .45 | .19 | .44 | .36 | .36 | .42 | .43 | |||||||||

| 12 | 8.87(4.81) | 1 | .22 | .40 | .32 | .29 | .39 | .37 | ||||||||||

| 13 | 0.49(1.06) | 1 | .17 | .15 | .13 | .17 | .17 | |||||||||||

| 14 | −0.04(0.85) | 1 | .91 | .72 | .80 | .94 | ||||||||||||

| 15 | −0.04(0.98) | 1 | .45 | .57 | .92 | |||||||||||||

| 16 | −0.00(1.00) | 1 | .60 | .58 | ||||||||||||||

| 17 | −0.06(0.92) | 1 | .87 | |||||||||||||||

| 18 | −0.04(1.02) | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

Note. Variables: 1. age; 2. female; 3. education; 4. income; 5. years living the United States; 6. household members; 7. Married; 8. Mobility; 9. chronic conditions; 10. acculturation; 11. cognitive activity; 12. social activity; 13. religious activity; 14. global cognition; 15. episodic memory; 16. working memory; 17. executive function; and 18. Italicized coefficients were not statistically significant. C-MMSE = C-Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 2 presents multivariate regression analysis results on five cognitive function variables. In general, high levels of engagement in social (B = .02, SE = .00), cognitive activities (B = .03, SE = .00), or overall engagement (B = .02, SE = .00) were associated with better global cognition. Similarly, significant relationships existed with episodic memory, working memory, executive function, and cognitive performance (C-MMSE) after controlling for socio-demographics and acculturation. Religious activity engagement was only significantly associated with working memory (B = .07, SE = .00), indicating frequently attending religious services may promote working memory. Interestingly, acculturation had significant positive correlations with all cognition measures in bivariate analyses (see Table 1, correlation coefficients ranging from .27 to .37, p <.0001), and in the multivariate regression analyses without activity variables entered (not shown in Tables). After controlling for activity measures and other variables, the significance of acculturation effects tapered off.

Table 2.

Multivariate Regression Analyses of Cognitive Function Domains.

| Global cognition |

Episodic memory |

Working memory |

Executive function |

C-MMSE |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | |

| Age | −.03(.00) | .002 | −.03(.00) | .000 | −.02(.00) | .000 | −.03(.00) | .000 | −.03(.00) | <.0001 |

| Female | −.01(.03) | .70 | .07(.03) | .03 | −.17(.03) | .000 | .01(.03) | .87 | .00(.03) | .89 |

| Education | .06(.00) | .000 | .06(.00) | .000 | .07(.00) | .000 | .07(.00) | .000 | .09(.00) | <.0001 |

| Income | .03(.01) | .01 | .03(.01) | .06 | .02(.00) | .19 | .05(.00) | .0004 | .01(.01) | .33 |

| Years living in the United States | .00(.00) | .94 | .00(.01) | .89 | −.00(.00) | .21 | −.00(.00) | .14 | .00(.00) | .04 |

| Household member | −.02(.01) | .02 | −.00(.01) | .75 | −.03(.01) | .001 | −.02(.01) | .03 | −.04(.01) | <.0001 |

| Married | .06(.03) | .05 | .05(.04) | .21 | .05(.04) | .20 | .05(.03) | .17 | .13(.04) | .004 |

| Mobility | −.10(.01) | .000 | −.09(.02) | .000 | −.09(.02) | .000 | −.13(.02) | .000 | −.11(.02) | <.0001 |

| Medical condition | −.01(.01) | .21 | −.02(.01) | .26 | −.01(.01) | .63 | −.02(.01) | .15 | −.00(.01) | .95 |

| Acculturation | .00(.00) | .37 | .00(.00) | .54 | .00(.00) | .23 | .00(.00) | .32 | .00(.00) | .80 |

| Cognitivea activity | .03(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | <.0001 |

| Social activitya | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .01(.00) | .003 | .02(.00) | .000 | .01(.00) | .0003 |

| Religious activitya | .05(.03) | .07 | .04(.04) | .24 | .07(.00) | .004 | .06(.03) | .09 | .07(.03) | .06 |

| Total activityb | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | <.0001 |

Note. C-MMSE = C-Mini-Mental State Examination.

model includes cognitive, social, and religious activity, and control variables.

model includes total activity engagement and control variables.

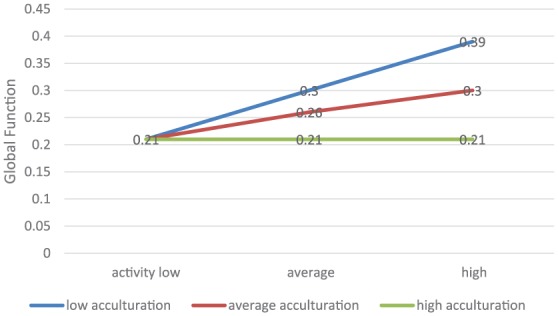

Table 3 presents the interaction effects between acculturation and activity engagement. Significant acculturation moderating effects were found on global cognition with cognitive (B = −.001, SE = .001), social (B = −.001, SE = .00), religious (B = −.001, SE = .005), and total activity (B = −.001, SE = .00); on episodic memory with cognitive (B = −.002, SE = .001), social (B = −.002, SE = .001), religious (B = −.02, SE = .01), and total activity (B = −.002, SE = .00); and on C-MMSE with cognitive (B = −.002, SE = .001), social (B = −.001, SE = .001), and total activity (B = −.002, SE = .00), but not on working memory and executive function. The coefficients on the interaction terms indicate that the relationships of activity engagement with global cognition, episodic memory, and C-MMSE varied by acculturation levels. Specifically, the associations were stronger for older adults who were less acculturated. For example, as shown in Figure 1, the relationship between total activity engagement and global function was constant for a high level of acculturation (e.g., M + 1SD = 28). For those with average acculturation level (M = 19), a slight increase in global cognition was associated with increased activity engagement. By contrast, among those with a low level of acculturation (e.g., M-1SD = 10), a steep increase was observed in global cognition along with increasing levels of total activity engagement, indicating greater benefits of activity engagement on global cognition. Similar patterns were observed among other significant interaction effects.

Table 3.

Interactions Between Acculturation and Activity Engagement on Cognitive Function Domains.

| Global cognition |

Episodic memory |

Working memory |

Executive function |

C-MMSE |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B(SE) | p | B(SE) | P | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | B(SE) | p | |

| Age | −.03(.00) | .000 | −.03(.00) | .000 | −.02(.00) | .000 | −.03(.00) | .000 | −.03(.00) | <.0001 |

| Female | −.01(.02) | .74 | .07(.03) | .02 | −.17(.03) | .000 | .00(.03) | .90 | −.00(.03) | .96 |

| Education | .06(.00) | .000 | .06(.00) | .000 | .07(.00) | .000 | .07(.00) | .000 | .07(.00) | <.0001 |

| Income | .03(.01) | .006 | .03(.01) | .03 | .02(.00) | .16 | .04(.01) | .005 | .02(.01) | .02 |

| Years living in the United States | .00(.00) | .94 | −.00(.01) | .85 | −.00(.00) | .19 | −.00(.00) | .16 | .00(.00) | .15 |

| Household member | −.02(.01) | .02 | −.00(.01) | .72 | −.03(.01) | .001 | −.02(.01) | .03 | −.02(.01) | .007 |

| Married | .06(.03) | .05 | .05(.04) | .21 | .05(.04) | .20 | .05(.03) | .17 | .13(.04) | .004 |

| Mobility | −.10(.01) | .000 | −.08(.02) | .000 | −.09(.02) | .000 | −.13(.02) | .000 | −.08(.02) | <.0001 |

| Medical condition | −.01(.01) | .18 | −.02(.01) | .23 | −.01(.01) | .61 | −.02(.01) | .16 | −.00(.01) | .55 |

| Acculturation | .00(.00) | .09 | .01(.00) | .13 | .00(.00) | .17 | .00(.00) | .42 | −.00(.00) | .69 |

| Cognitive activity | .03(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | .000 | .03(.00) | <.0001 |

| Social activity | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .01(.00) | .002 | .02(.00) | .000 | .01(.00) | .0002 |

| Religious activity | .05(.03) | .06 | .04(.04) | .22 | .07(.04) | .04 | .06(.03) | .09 | .07(.03) | .03 |

| Total activity | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | .000 | .02(.00) | <.0001 |

| Acculturation × cognitivea | −.001(.000) | .0018 | −.002(.001) | .0005 | −.000(.001) | .99 | −.000(.001) | .38 | −.002(.001) | <.0001 |

| Acculturation × socialb | −.001(.000) | .0021 | −.002(.001) | .0011 | −.001(.001) | .38 | .001(.001) | .33 | −.001(.001) | .005 |

| Acculturation × religiousc | −.001(.005) | .0013 | −.02(.01) | .0002 | −.005(.006) | .42 | .001(.005) | .82 | −.007(.01) | .21 |

| Acculturation × total activityd | −.001(.000) | .000 | −.002(.000) | .000 | −.000(.000) | .22 | −.000(.000) | .78 | −.002(.000) | <.0001 |

Note. C-MMSE = C-Mini-Mental State Examination.

model adds the interaction between cognitive activity and acculturation to model 1 in Table 2.

model adds the interaction between social activity and acculturation to model 1 in Table 2.

model adds the interaction between religious activity and acculturation to model 1 in Table 2.

model adds the interaction between total activity and acculturation to model 2 in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Interaction between total activity engagement and acculturation on global cognition.

Discussion

This study adds to a substantial body of evidence about the cross-sectional correlations between activity engagement and cognitive function in later life. Particularly, increased cognitive activities was related to better perceptual speed or executive function (e.g., Ghisletta, Bickel, & Lovden, 2006), and social participation was related to both memory and executive function (e.g., Bourassa et al., 2017; Brown et al., 2012). The present study extends previous findings by documenting the overall effects of cognitive and social activity engagement on global, memory, and executive functions, and examining the moderating effect of acculturation. Although findings cannot be interpreted as unidirectional due to the lack of an experimental and longitudinal design, this study demonstrates that participation in more cognitive activities such as reading, playing games, and more social activities such as going out and visiting community centers, are associated with better overall functioning and performance as well as episodic memory, working memory, and executive function, while more frequent attendance in religious services is only related to working memory. Although there is evidence suggesting that religious involvement is associated with better cognitive function among White, Black, and Hispanic elders, to our knowledge there have been no analyses of the relationship among Chinese older adults living in the United States. Despite the fact that religious attendance was measured with only one item and that attendance level was quite low in the study sample, the findings about religious activity and cognition were somehow consistent with the literature among other aging populations such as older Mexican Americans (e.g., Hill, Burdette, Angel, & Angel, 2006).

Perhaps more importantly, we found that high levels of engagement in three types of activities are more beneficial to the less acculturated older adults, especially in global cognition, cognitive performance, and episodic memory. Although acculturation had significant bivariate associations with all cognitive domains, the statistically significant correlations disappeared when estimating the activity variables in the multivariate regression analysis models, indicating that active engagement in everyday activities may buffer the negative effects of low acculturation, if there is any, on overall cognition and episodic memory.

Episodic memory tested through EBMT is a brief measure of verbal memory (Gfeller & Horn, 1997). It refers to “the acquisition of propositional (or declarative, cognitive, or symbolically representable) information on a particular occasion and its reproduction on a subsequent occasion” (Wheeler, Stuss, & Tulving, 1997, p. 332). “It involves remembering by re-experiencing and mentally traveling back in time” (Wheeler et al., 1997, p. 349). That is, previous experience is important and one is re-experiencing something that has happened before in the present experience (Wheeler et al., 1997). For less acculturated older adults, activity participation may enhance episodic memory through the connection with previous experience and reliance on subjective feelings. By contrast, working memory and executive function share a common underlying cognitive ability or attentional ability, that is, the ability to maintain a goal in an active state or to resolve interference when there is conflict between a predominant response and task demands (McCabe, Roediger III, McDaniel, Balota, & Hambrick, 2010), which may not depend on acculturation. It seems that activity engagement effects on working memory and executive function are universal for Chinese older adults at different acculturation levels.

Cognitive interventions for mild cognitive impairment and preventions among persons with normal cognitive aging often target cognitive training on memory, especially episodic memory, to improve cognitive function and prevent the development of dementia (Belleville et al., 2006). Based on our findings, everyday activity can be incorporated into cognitive preventions, especially among those less acculturated. Although the acculturation effects are mixed on health outcomes, including cognition, previous research has shown that bilingualism is a potent source of cognitive reserve, and as compared with monolinguals, bilinguals are better on tasks that require executive control or selective attention, displaying dementia symptoms later in age, and showing significantly better cognitive recovery after stroke (Bialystok, Abutalebi, Bak, Burke, & Kroll, 2016). While it is difficult for recent older adult immigrants to become bilingual or learn a new culture right away, active engagement in everyday activities may compensate for the cognitive disadvantages of lacking other coping resources indicated by low acculturation or being monolinguals. Older adults, especially recent immigrants, may face difficulties in involving resource-demanding activities, like volunteering or community work, which mostly rely on their social networks and certain capacities or skills, but engagement in social and leisure activities in everyday life is accessible and practicable. Thus, efforts are needed to increase older adults’ exposure to and involvement in cognitively simulated and socially integrated activities or environments, which may help to preserve their cognitive function.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the study findings on the activity-cognition relationships may be bidirectional, that is, older adults with better cognitive function might be more likely to engage in everyday activities. Longitudinal analyses involving multiple waves of data will provide a strong argument to address causal relationships between activity engagement and indicators of cognitive function. Second, although it is a population-based sample of Chinese older adults in the United States, the generalizability of study findings may not go beyond the greater Chicago area, where the PINE study participants were recruited. Third, other factors, that are not included in this study, such as geographic locations, neighborhood conditions, may also affect activity engagement and cognitive function, or serve as the mechanisms through which activities affect cognition (Weden et al., 2017). Finally, our measures might not be inclusive; for example, the cognitive tests did not capture the full range of cognitive abilities, and clinical evaluations of cognitive impairment were missing. And types of activity were limited; some activities like volunteering and community work were not surveyed.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes to research and practice on cognitive function among older Chinese Americans and highlights the importance of activity engagement in maintaining cognitive function. The investigation on the moderation role of acculturation improves our understanding that engagement in everyday activities such as reading, playing games, and going out are particularly beneficial to those less acculturated in maintaining global cognition and episodic memory. Indeed, active engagement with life and maintenance of high physical and cognitive function are the important and interrelated components of the successful aging model (Rowe & Kahn, 1997). If older adults, older immigrants in particular, are provided with increased opportunities for various activities, they are likely to sustain and prolong their physical and cognitive functioning. Providing opportunities for meaningful activities and building friendly living environments for older adults are substantial public health issues, and the health benefits will accrue to both individuals and society at large.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Aartsen M., Smits C., van Tilburg T., Knipscheer K., Deeg D. (2002). Activity in older adults: Cause or consequence of cognitive functioning? A longitudinal study on everyday activities and cognitive performance in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 57, P153-P162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraído-Lanza A. F., Armbrister A. N., Flórez K. R., Aguirre A. N. (2006). Toward a theory-driven model of acculturation in public health research. American Journal of Public Health, 96, 1342-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraído-Lanza A. F., Chao M., Florez K. (2005). Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Social Science & Medicine, 61, 1243-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert M., Smith L. A., Scherr P. A., Taylor J. O., Evans D. A., Funkenstein H. H. (1991). Use of brief cognitive tests to identify individuals in the community with clinically diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Neuroscience, 57, 167-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson N. D., Damianakis T., Kroger E., Wagner L. M., Dawson D. R., Binns M. A., . . . The BRAVO Team. (2014). The benefits associated with volunteering among seniors: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1505-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath P. A., Deeg D. (2005). Social engagement and health outcomes among older people: Introduction to a special section. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 24-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belleville S., Gilbert B., Fontaine F., Gagnon L., Menard E., Gauthier S. (2006). Improvement of episodic memory in persons with mild cognitive impairment and healthy older adults: Evidence from a cognitive intervention program. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22, 486-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok E., Abutalebi J., Bak T. H., Burke D. M., Kroll J. F. (2016). Aging in two languages: Implications for public health. Ageing Research Reviews, 27, 56-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa K. J., Memel M., Woolverton C., Sbarra D. A. (2017). Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging and Mental Health, 21, 133-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. L., Gibbons L. E., Kennison R. F., Robitaille A., Lindwall M., Mitchell M. B., . . . Piccinin A. M. (2012). Social activity and cognitive functioning over time: A coordinated analysis of four longitudinal studies. Journal of Aging Research, 2012, Article 287438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E.-S., Dong X. (2014). A battery of tests for assessing cognitive function in U.S. Chinese older adults—Findings from the PINE study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 69(Suppl. 2), D23-D30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu H. F. K., Lee H. C., Chung W. S., Kwong P. K. (1994). Reliability and validity of the Cantonese version of mini-mental state examination—A preliminary study. Journal of Hong Kong College of Psychiatry, 4(Spec No 2), 25-28. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Bergren S. M., Chang E.-S. (2015). Levels of acculturation of Chinese older adults in the greater Chicago area—The population study of Chinese elderly in Chicago. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63, 1931-1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Wong E., Simon M. A. (2014). Study design and implementation of the PINE study. Journal of Aging and Health, 26, 1085-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson K. R., Sarmiento O. L., Ayala G. X. (2004). Acculturation and physical activity among North Carolina Latina immigrants. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 2509-2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M., Anthony J. C., Parhad I., Duffy B., Gruenberg E. M. (1985). The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 33, 228-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L., Paillard-Borg S., Winblad B. (2004). An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. The Lancet Neurology, 3, 343-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried L. P., Borhani N. O., Enright P., Furberg C. D., Gardin J. M., Kronmal R. A., . . . Weiler, P. G., et al. (1991). The cardiovascular health study: Design and rationale. Annals of Epidemiology, 1, 263-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gfeller J. D., Horn G. J. (1997). The East Boston Memory Test: A clinical screening measure for memory impairment in the elderly. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 52, 191-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisletta P., Bickel J-F., Lovden M. (2006). Does activity engagement protect against cognitive decline in old age? Methodological and analytical considerations. Journal of Gerontology B Psychological Science, 61, 253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glei D. A., Landau D. A., Goldman N., Chuang Y. L., Rodríguez G., Weinstein M. (2005). Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: An analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. International Journal of Epidemiology, 34, 864-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havighurst R. J. (1961). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 1, 8-13. [Google Scholar]

- Hill T. D., Burdette A. M., Angel J. L., Angel R. J. (2006). Religious attendance and cognitive functioning among older Mexican Americans. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 61(1), P3-P9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James B. D., Wilson R. S., Barnes L. L., Bennett D. A. (2011). Late-life social activity and cognitive decline in old age. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 17, 998-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y., Chiriboga D. A. (2011). Social activity and depressive symptoms in Korean American older adults: The conditioning role of acculturation. Journal of Aging and Health, 23, 767-781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Dattilo J., Heo J. (2011). Education and recreation activities of older Asian immigrants. Educational Gerontology, 37, 336-350. [Google Scholar]

- Korten A. E., Henderson A. S., Christensen H., Jorm A. F., Rodgers B., Jacomb B., Mackinnon A. J. (1997). A prospective study of cognitive function in the elderly. Psychological Medicine, 27, 919-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper J. S., Zuidersma M., Oude Voshaar R. C., Zuidema S. U., van den Heuvel E. R., Stolk R. P., Smidt N. (2015). Social relationships and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Research Reviews, 22, 39-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. W., Ding D., Wu B., Dong X. (2017). Change of cognitive function in U.S. Chinese older adults: A population-based study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences, 72(Suppl. 1), S5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides K. D., Eschbach K. (2005). Aging, migration, and mortality: Current status of research on the Hispanic paradox. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 60(Spec No 2), S68-S75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe D. P., Roediger H. L., McDaniel M. A., Balota D. A., Hambrick D. Z. (2010). The relationship between working memory capacity and executive functioning: Evidence for a common executive attention construct. Neuropsychology, 24, 222-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M., Christensen K. (2007). Social activity and healthy aging: A study of aging Danish twins. Twin Research and Human Genetics: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 10, 255-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow-Howell N., Gehlert S. (2012). Social engagement and a healthy aging society. In Prohaska T., Anderson L., Binstock R. (Eds.), Public health for an aging society (pp. 205-227). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mui A. C. (1996). Depression among elderly Chinese immigrants: An exploratory study. Social Work, 41, 633-645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui A. C., Kang S. (2006). Acculturation stress and depression among Asian immigrant elders. Social Work, 51, 243-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I., Breslau N. (1966). A Guttman health scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology, 21, 556-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37, 433-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. (1984). Symbol Digit Modalities Test: Manual (Revised). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (1987). Wechsler Memory Scale—Revised: Manual. San Antonio, CA: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Weden M. M., Miles J., Friedman E., Escarce J. J., Peterson C., Langa K. M., . . . Shih R. A. (2017). The Hispanic paradox: Race/ethnicity and nativity, immigrant enclave residence and cognitive impairment among older US Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65, 1085-1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler M. A., Stuss D. T., Tulving E. (1997). Toward a theory of episodic memory: The frontal lobes and autonoetic consciousness. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 331-354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]