Abstract

Schools have long been critical partners for public health authorities in achieving widespread vaccination. In the mid-20th century, however, public schools also served as sites of large-scale experiments on novel vaccines. Through examining the experimental diphtheria, polio, and measles vaccine trials, I explored the implications of using schools in this manner, as well as the continuities and discontinuities among the three cases. Common to all of them was that the use of schools brought decision-making into the public sphere, subjecting parents to social pressures and the influences of school officials and community members. However, the effects of using schools varied as well, as their social and institutional significance interacted differently with the narratives surrounding each disease, the public’s changing perception of medicine and science, and society’s changing values. These insights show not only the power of public institutions to influence opinions and perceptions, but also the subtle forces that one’s authority figures, peers, and community members may bring to a seemingly private decision-making process. These considerations are relevant to health interventions today, such as the complex debate over community consent in global health research. (Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1015–1022. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304423)

In June of 2015, California governor Jerry Brown signed into law one of the nation’s toughest and most controversial vaccination laws, barring parents from obtaining religious and personal-belief exemptions for school vaccination requirements.1 Schools have long been critical partners for public health authorities in achieving widespread vaccination. In the mid-19th century, local municipalities began imposing school vaccination requirements to prevent smallpox outbreaks.2 Schools have also served as sites of mass vaccination campaigns. In 1951, the Los Angeles Times reported that a smallpox vaccination drive would visit 105 Los Angeles, California, schools and vaccinate about 35 000 students.3

In the mid-20th century, however, public schools served an additional function: as sites of large-scale experiments on novel vaccines. Through three examples of trials testing different vaccines—the experimental diphtheria, polio, and measles vaccines—I explored the implications of using schools in this manner. I also examined the continuities and discontinuities among the three cases. Common to all of them was that the use of schools brought decision-making into the public sphere. School officials played a central role in parents’ decisions, and parents had to contend with social pressures, or subtle coercion, to participate. However, the effects of using schools varied as well, as their social and institutional significance interacted differently with the narratives surrounding each disease, the public’s changing perception of medicine and science, and society’s changing values.

WILLIAM HALLOCK PARK’S DIPHTHERIA ANTITOXIN TRIAL

In the fall of 1921, a team of New York City physicians under the leadership of Board of Health laboratory director William Hallock Park entered the city’s public schools and began vaccinating thousands of schoolchildren a day with an experimental product thought to confer immunity against diphtheria. Park had been developing the diphtheria toxin–antitoxin for several years and had tested it on institutionalized populations. Bringing it to New York City’s public schools was his attempt at a large-scale test to prove efficacy.4 Park and his team tested their toxin–antitoxin on about 50 000 schoolchildren throughout the city, obtaining parental permission from each one of them.5 Many parents were skeptical of the state’s vaccination efforts during this time, and the antivaccination movement exhibited widespread strength.6 But partnering with public schools introduced a host of characters and influences into families’ decisions on whether to participate, with a striking result.

Parents in the early 20th century were accustomed to receiving information from, and trusting in, schools and other governmental institutions with regard to their children’s health. Toward the end of the 19th century, in response to Progressive Era school and health reforms, schools became seen as bastions against communicable diseases and spaces in which physical and mental health improvements could and should be made.7 Physicians employed by schools or the health department provided children with comprehensive examinations to detect “physical defects” and communicable diseases (Image 1).8 Collaborating with school nurses, doctors, and parents, teachers often made common diagnoses as well.9

IMAGE 1—

A nurse inspecting the throats of a line of children in class for signs of diphtheria in 1917. Courtesy of The New York Academy of Medicine Library. Printed with permission.

Furthermore, as arms of the state, schools held a great deal of power in communities, especially in the early 20th century, as laws mandating attendance were adopted and strengthened nationwide.10 Michel Foucault suggested that the ways in which children are taught and schools designed convey power to authority figures, including principals and teachers. Foucault argued that schools are among many societal institutions aimed at “controlling or correcting the operations of the body.”11

Thus, when Park obtained the endorsement of principals and schoolteachers, parents were more inclined to listen.12 Many principals eagerly agreed to help convince their students’ parents to provide permission, writing letters to parents in which they emphasized “their personal confidence in the procedure.”13 Schoolteachers handing out consent forms to children was likely seen as an implicit endorsement as well.14 In a publication in AJPH, Park et al. asserted that

the success or failure in getting a favorable response from the children or their parents, depends largely on the interest which the principal, assistant principal and the teachers take in the matter.15

School officials’ active support for the trial was so valuable that Park reported obtaining consent from three fourths of the parents when principals and teachers were enthusiastic about it, but only one fourth when they were not.16

There is a long history of school and government authorities using schools and schoolchildren to influence parental behavior. Schools were a central focus of Progressive Era reforms in part because they offered a chance for the state to intervene in the care of children. In Park’s 1920 volume, Charles F. Bolduan describes that schools are

. . . made the center of rallies, celebrations, and similar “features” . . . [so that] children serve as carriers of health messages into the homes of their parents. . . . Whenever possible the message carried by the leaflet should also be given directly to the children, in the form of a simple lesson, which they can understand and which they can then carry into the home by word of mouth.17

In the AJPH publication by Park et al., they appear to understand how schoolchildren acting as intermediaries would be beneficial for the trial:

. . . it was deemed wise to acquaint as many parents and others as possible, with the value of the Schick test and the toxin-antitoxin injections. No better way seemed available than to use the schools as the means of doing this. If each pupil presented his parents with a circular picturing the danger from diphtheria, describing the preventive treatment and asking for permission to administer this treatment if the family physician approved, it would mean that nearly a million adults and a million children would have the arguments for the use of the toxin-antitoxin vaccine presented to them in a favorable way.18

The researchers thus leveraged schools as sites in which they could use children to carry home, and elsewhere in the community, positive messages about participating in the trial. The paternalism that schools brought to the decision-making process had the effect of subtly coercing parents to participate. Open-minded, enthusiastic students would help convince parents of the importance of taking part in the trial.

Park’s use of schools had its critics for these very reasons. A letter about the Schick test for diphtheria19 from the Medical Liberty League, an antivaccination organization, states,

The public schools are the great objective in the Schick test campaign. . . . In their invasion of the public schools, the Schick test enthusiasts first aim to make an alliance with the school authorities. . . . Teachers have a serious moral responsibility in this matter. They have the confidence of the parents of their pupils to a remarkable degree. They will not want to be misled by the propaganda of Schick test advocates into doing anything to abuse the confidence parents and pupils so generally repose in them. . . . It is the school that is public—not the child.20

This last sentence refers to a common antivaccination argument, that the decision of whether to vaccinate one’s child is one for parents to make privately, not the state to make publicly. In this case, remarkably, the decision is whether to participate in human experimentation. Implementing the trial in schools brought the decision-making process to schools as well, as a child’s participation was not just up to her parents, but also influenced by her principal, teacher, and other families. In a sense, the child’s body itself becomes public.

It is important to note as well that Park aimed to present the trial “in a favorable way,” through the use of schools, not just to obtain more trial participants, but also to familiarize families with the vaccine, thus setting the stage for future vaccination efforts.21 Indeed, he saw future vaccination campaigns as a natural extension of his experimentation in these schools. This sentiment was reflected in the consent form’s language as well.22 Schools therefore played a critical role in, as Jeffrey Baker has stated, Park’s “blurr[ing of] the line between clinical study and immunization campaign.”23

THE SALK POLIO VACCINE TRIAL

A little more than 30 years later, schoolchildren participated in another vaccine trial, this time all across the United States as part of one of the largest medical experiments in history. Organized and carried out in public schools by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, the field trial tested the efficacy of Jonas Salk’s vaccine for poliomyelitis.24 Public schools once again played a central role, similarly shaping parents’ perceptions of the trial. However, in contrast to Park’s diphtheria trial, schools were not as responsible for persuading parents to participate. In fact, parents leapt at this chance of protecting their children from this feared disease. Given the media’s extensive coverage of the trial, there also could not have been any question among parents that this was indeed a trial, as opposed to a vaccination campaign, which was more likely in the case of diphtheria. But schools did obscure the risks of participation, while ensuring that participation was nearly a given—indeed, almost an obligation.

Particularly evident in the polio trial was that the use of schools brought the process of educating parents about the trial out of doctors’ private offices and into the public sphere. Along with schools, the media played an important role in familiarizing parents with the trial. While families received a great deal of information, there was a widespread lack of agreement and clarity in describing the trial’s scientific objectives,25 and there was no one to privately answer each parent’s questions and help guide them to the correct decision.26 In fact, the information parents received failed to adequately describe legitimate safety concerns among physicians and researchers familiar with the production of the vaccine.27 Furthermore, there was some doubt as to whether parents even adequately understood the information sent out from the schools and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. One 1958 study examining parental participation stated,

It seems safe to infer that many of them [parents of lower socioeconomic status] must have had a great deal of difficulty in reading and understanding the printed materials sent to them from the schools.28

When it came time to consent, these sources and discussions with friends and neighbors were largely what parents based their decisions on; most did not talk about the trial with their family physicians, who may have been more alert to legitimate risks of which parents should be made aware. One study found that not only did fewer than half of the parents who gave consent speak with their doctors about the trial, but consenting parents were also more likely to talk with their friends, relatives, or neighbors.29 Housing the trial in schools required parents to independently seek out more reliable information from their family physicians, which they would have done only if they did not believe the information presented in the media and sent from school. In fact, almost 30% of mothers who gave consent talked with no one, suggesting that they were satisfied with what they read and heard from the media and from their children’s school.

In addition to obscuring the risks of participation, the use of schools in the polio trial introduced a significant degree of subtle coercion to participate. Given the extent to which parents discussed the trial with their friends and neighbors, they were likely influenced by how others perceived the trial and others’ decisions to participate. Discussing the trial with others made it publicly evident whose children ultimately partook in the trial and whose did not; parents knew that their decision not to participate would likely be known and judged by their community. And at a time of intense nationalism following World War II, participating was seen, and presented by the media, as a community deed or even an obligation: all members of the public could come together in schools to play their part in fighting against the deadly childhood disease. Parents who did not allow their children to participate were likely seen as unpatriotic in this respect. Although friends and neighbors doubtless also played a role in the decision-making process in the diphtheria and measles cases, it likely would have been less significant, as those trials did not capture the nation’s attention quite like polio did.

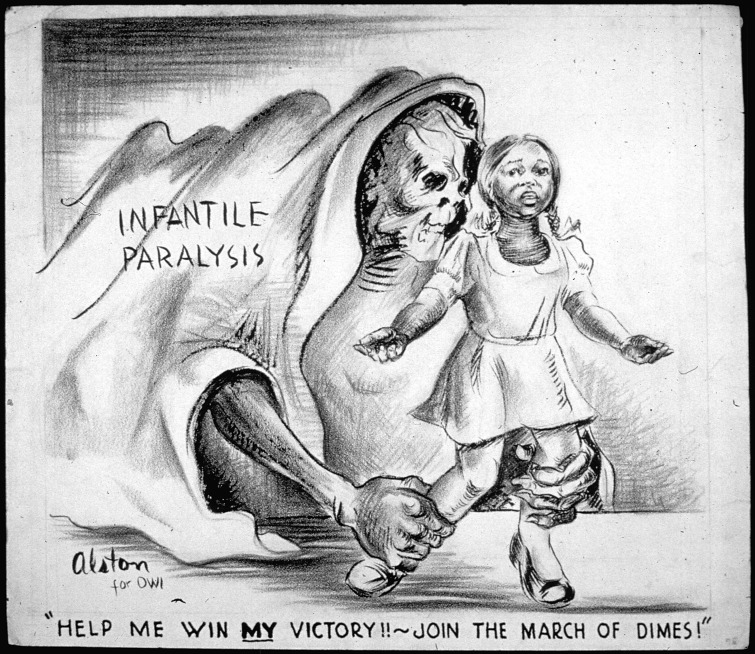

The use of schools, with the media’s help, reinforced this sense that participation was an act of patriotism and civic responsibility. The public and communal nature of schools enhanced the celebration and spectacle that coincided with the trial; children and parents lined up in schools and were given the vaccine (or the placebo) one by one, as the media took pictures and onlookers smiled in wonder.30 In many ways, participating in the trial could be considered as showing solidarity with one’s community, as people were literally standing in line together to play a role in finding a cure for the disease. Just as individuals were called on to do their part in the war effort a decade earlier, individuals were now called on to do their part in the name of scientific advancement.31 That schools symbolically represented the future of the country contributed to this sentiment. The US Office of War Information even commissioned a poster in 1943 encouraging Americans to join the March of Dimes, likening a child’s struggle against polio to the country’s struggle in World War II (Image 2).

IMAGE 2—

In this cartoon commissioned in 1943 by the US Office of War Information, the girl’s struggle with infantile paralysis (polio) is likened to the country’s struggle in World War II. Charles Henry Alston, National Archives and Records Administration, via Wikimedia Commons.

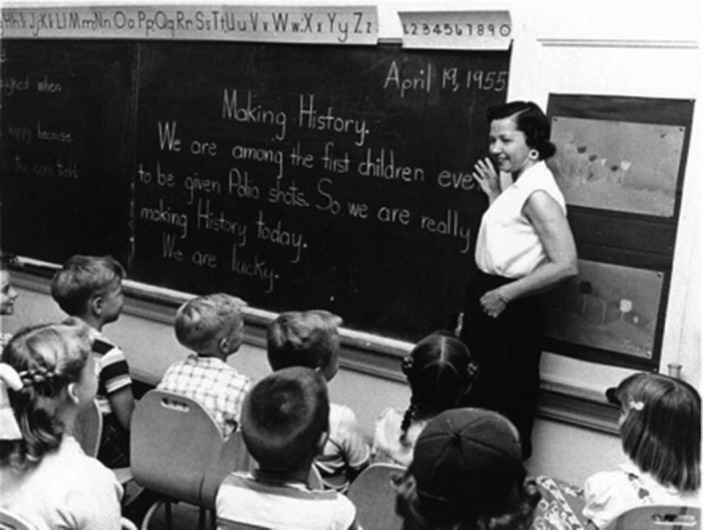

Moreover, in an iconic image of the nation’s fight against polio, a teacher has written on a blackboard: “Making History. We are among the first children ever to be given Polio shots. So we are really making History today. We are lucky” (Image 3). Although the picture was taken on April 19, 1955, which was after the trial had been completed, it nonetheless illuminates teachers’ and children’s perceptions of the polio vaccine. The image suggests that the teacher assumed everyone in the class was receiving the vaccine. It also demonstrates how children were told that it was a privilege to receive it, just as the trial’s consent form mailed home to parents was in fact a “request to participate form,” and that teachers saw receiving the vaccine as a classroom responsibility to “make history.”32

IMAGE 3—

A teacher’s message for her students regarding their historic role in the fight against polio. Courtesy of March of Dimes. Printed with permission.

In sum, as in the diphtheria trial, but perhaps even more so, the use of schools made public the learning and decision-making process, as well as who ultimately participated. However, unique to this case was how schools helped make the trial, and participation in it, a cultural phenomenon. This, in turn, added a level of subtle coercion as well.

MEASLES VACCINE TRIALS IN THE 1960S

Following their success in developing a polio vaccine, researchers turned to measles, carrying out several trials of potential vaccines across the country throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s. After a period of testing among institutionalized populations, researchers similarly turned to public schools as sources of participants and locations for the trials. Using schools in these trials echoed experiences in the diphtheria and polio trials, but there were important departures.

As in the polio vaccine trial in 1954, the use of public schools helped depict many of the measles trials as community events in which participating parents and their children were contributing to something greater than themselves. In Fred R. McCrumb’s proposal for a measles vaccine study in the public schools of St. Joseph, Missouri, the University of Maryland physician wrote, “The community nature of the study is recognized and the enthusiastic support of community leaders attests to the desire of many to contribute to the program.”33 In what appears to be the draft of an informational circular or trial proposal, McCrumb wrote,

The proposed study of measles vaccine in St. Joseph is . . . the opportunity for citizens of a progressive community to be pioneers in extended research on a very promising but still quite new vaccine against measles.34

The use of “pioneer” invokes sentiments of the polio trial, reflecting the respect and admiration participants were given because of their willingness to serve as test participants for the well-being of others. That schools were used heightened this perception of participants as pioneers, as schoolchildren were both the pride and future of communities. McCrumb also noted that the school board had “the important role” of being “supporters of the program,”35 and in a posttrial letter to St. Joseph’s Superintendent of Schools, McCrumb expressed his appreciation for the help of principals and teachers.36

The following year, instead of using public schools to persuade parents to participate, McCrumb used them to persuade Baltimore, Maryland’s Commissioner of Health to allow trials among the city’s children. In describing what work had already been done on finding a safe and effective vaccine, McCrumb stated,

It will be of additional interest to you that 480 of these vaccinees were school children in St. Joseph, Missouri and that the actual work of bleeding, vaccinating, and examining was carried out in the public and parochial schools of that community. I might add that our program has been received enthusiastically by the people of St. Joseph.37

It appears that McCrumb is suggesting that the fact that he carried out tests in schools demonstrates the safety, legitimacy, and public acceptance of the experimental vaccine. In effect, he capitalizes on this use of schools as a method to convince the Baltimore commissioner to allow his city’s children to participate in a trial.

Joseph Stokes, physician-in-chief of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, also conducted measles vaccine trials during this time, using various institutions in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, region. Parents of children who attended school in Haverford Township, Pennsylvania, were asked to record their child’s temperatures on a “special report card.”38 In using the term “report card,” Stokes took advantage of schools and school practices as familiar and comfortable spaces for families.

It is also worth noting that the use of schools may have similarly facilitated the perception that participating in the trials was a patriotic act. In a Cold War propaganda piece written for a Russian audience, author David Paul described the children and schools of America leading the way to find a cure for measles.39 While parents of potential trial participants would not have seen the article and it contains a great deal of hyperbole, the article may have captured some truth in the ethos surrounding participation.

Nonetheless, schools were not used as sites of measles trials to the same extent as for the diphtheria and polio trials, and their effects on altering perceptions and participation were most likely less severe. The measles trials that took place in schools, including private schools, were much smaller and significantly less publicized than the diphtheria and polio trials. Other locations for testing the measles vaccine were also used. For example, instead of using the schools of Baltimore, McCrumb carried out a large-scale test of the measles vaccine in the University of Maryland Hospital, and solicited volunteers from well-baby and inoculation clinics.40 For the trials of vaccines produced in subsequent years, schools were not significantly used either.41 Several explanations may account for this shift, including a lack of urgency for a measles vaccine; a changing American culture of obligation, responsibility, and community identification; and a greater awareness of ethical problems among the public and researchers in relation to the use of children and institutionalized populations.

The urgency of developing a vaccine for polio and the nationalism that supported it contributed to the perception that it was appropriate, even natural, to conquer the disease in schools as a grand program of scientific and medical advancement. But, as the 1960s progressed, the patriotic fervor that had fueled a number of scientific initiatives and compelled families to conform to what their country expected of them was not as strong of a sentiment anymore. As Elaine Tyler May describes, “By the late 1960s, many among this new, ‘uncontained’ generation had rejected the rigid institutional boundaries of their elders.”42 The rise of countercultural movements split this unity apart and challenged authority figures, including those in medicine and science. The ethos of community involvement, obligation for the greater good, and doing what one’s neighbor was doing that drove millions to participate in the polio vaccine trial had diminished significantly. More simply, neither the public nor researchers feared measles as much as diphtheria and polio; rather, measles was seen as a fact of life.43

The decline in the use of schools can also be attributed to a shift in medical ethics around this time. Cases of ethically troublesome human participants research, including hepatitis experiments at Willowbrook State School and cancer studies at Sloan-Kettering Hospital, made headlines both among researchers and the public. Ethical guidelines developed in the 1960s held greater sway nationally and internationally, and physicians became increasingly regulated by outside forces, including bioethics committees and lawyers.44 In turn, researchers were more hesitant to use vulnerable populations such as children and the mentally disabled, and were more careful to explain the risks of participating in trials.

Indeed, the language used to describe the measles vaccine trials to the public reflect these changes. In the various publications and information circulars produced for the measles vaccine trials, their experimental nature was less obscured than those circulated during the polio and diphtheria vaccine trials. For example, McCrumb wrote,

We should point out that many questions remain to be answered. The proposed study of measles vaccine in St. Joseph is not the large scale use of a proven product but rather the opportunity for citizens of a progressive community to be pioneers in extended research on a very promising but still quite new vaccine against measles.45

Furthermore, for a vaccine trial using children of St. Vincent’s Infant Home and families in Baltimore, McCrumb was required to submit a document to the University of Maryland School of Medicine that asked researchers, “Is the human beings’ informed consent obtained?”46 That the word “informed” is included and underscored signals a shift in how the field perceived human experimentation and the level of protection human participants should be given.

Although there is no direct evidence of vaccine researchers discussing the changing climate of medical ethics during this time, it is reasonable to conclude that they were indeed aware of the trend. In 1978, The Belmont Report was published, which specified a framework of moral principles to which clinical research should conform. Importantly, young children were deemed as needing protection because they lack the skills to comprehend the risks of medical research.47 The report also calls for the protection of prisoners, suggesting that “under prison conditions they may be subtly coerced or unduly influenced to engage in research activities for which they would not otherwise volunteer.”48 Although schools are not mentioned, it is significant that the document identifies the environment in which research is carried out as worthy of ethical consideration.

CONCLUSIONS

Schools played a crucial yet varied role in how parents perceived and participated in the mid-20th century’s major vaccine trials. In Park’s diphtheria trial, New York City’s public schools took on a more paternalistic, Progressive Era role, in which they were used to persuade hesitant parents of the importance of participating in the trial. In Salk’s 1954 polio trial, aided by the public’s fear of polio, the era’s patriotism, and the media, schools helped make participating in the trial a cultural phenomenon and civic obligation. In the measles trials of the 1960s, schools played a lesser role, as there was much less urgency to develop a measles vaccine and a greater awareness of ethical considerations when conducting research.

Although today’s more stringent protocols for the conduct of vaccine trials would likely prevent using schools in the same manner, these cases are still relevant to how we conduct health interventions today. Indeed, these insights show not only the power of public institutions to influence opinions and perceptions, but also the subtle forces that one’s authority figures, peers, and community members may bring to a seemingly private decision-making process. These considerations are relevant, for example, to the complex debate over community consent in global health research. For cultures having “key values such as loyalty, compassion, and solidarity” as “more dominant than autonomy,” adapting the process of obtaining consent (e.g., by obtaining the consent of community leaders) is critical.49 But this essay points to the potential risks of empowering community leaders and institutions too greatly, without ensuring the informed consent of the individual as well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I received support from the Ruth Marcus Kanter College Alumni Society Grant from the Penn Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships.

I gratefully acknowledge the mentorship and recommendations of Jonathan D. Moreno and Meghan Crnic. Many thanks also to the AJPH reviewers for their helpful input.

Footnotes

See also Baker, p. 976.

ENDNOTES

- 1. Phil Willon and Melanie Mason, “California Gov. Jerry Brown signs new vaccination law, one of the nation’s toughest,” Los Angeles Times, June 30, 2015, http://www.latimes.com/local/political/la-me-ln-governor-signs-tough-new-vaccination-law-20150630-story.html (accessed December 5, 2016)

- 2. James G. Hodge and Lawrence O. Gostin, “School Vaccination Requirements: Historical, Social, and Legal Perspectives,” Kentucky Law Journal 90, no. 4 (2001–2002): 831–890. [PubMed]

- 3.“Smallpox Vaccinations Begin in City Schools ” Los Angeles Times 4, 1951. January , A1 [Google Scholar]

- 4. For an account of the history of diphtheria control and the development of the toxin–antitoxin, see Evelynn Hammonds, Childhood’s Deadly Scourge: The Campaign to Control Diphtheria in New York City, 1880–1930 (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999).

- 5. William H. Park, M.C. Schroder, and Abraham Zingher, “The Control of Diphtheria,” American Journal of Public Health 13, no. 1 (1923): 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6. For an account of the history of antivaccination sentiment during the 20th century, see James Colgrove, State of Immunity: The Politics of Vaccination in Twentieth-Century America (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2006).

- 7. For an account of the history of health care in public schools, see Richard Meckel, Classrooms and Clinics: Urban Schools and the Protection and Promotion of Child Health, 1870–1930 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013). For an account on Progressive Era school reforms, see John L. Rury, “Transformation in Perspective: Lawrence Cremin’s Transformation of the School,” History of Education Quarterly 31, no. 1 (Spring, 1991): 66–76.

- 8. The belief that schools should play a role in child health was especially strong after the first World War: L. Emmett Holt, “Safeguarding the Health of Our School Children,” Child Health Organization (1918), Series 755: Bureau of Reference, Research and Statistics, Box 44, Board of Education Records, New York City Municipal Archives.

- 9.Hortense Hilbert, “Responsibility of the Teacher for Child Health,”. Childhood Education. 14, no. 1 (1937): 403. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Michael S. Katz, A History of Compulsory Education Laws, Fastback Series, No. 75, Bicentennial Series (Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa, 1976), 21.

- 11. Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1995), 136.

- 12. Park first obtained the support of I. H. Goldberger of the Bureau of Educational Hygiene of the Department of Education, who “prepares the way by obtaining permission for us to do the work in the school.” One of Park’s colleagues would then meet with “the principal and explain fully the objects we have in view. Literature is left for the teachers. Either the principal or the physician meets the teachers in a conference, gives them the necessary information and tries to arouse their enthusiasm”: Park, Schroder, and Zingher, “The Control of Diphtheria,” 27.

- 13. Bureau of Child Hygiene, “The Schick Test and the Administration of Toxin Antitoxin,” in Annual Report of the Department of Health of the City of New York for the Year of 1920 (New York, NY: Department of Health, 1921), 222, New York City Municipal Archives.

- 14. The consent form was sent along with an information circular describing the importance of diphtheria prevention efforts: William H. Park, “Prevention of Individual Infectious Diseases,” in ed. William H. Park, Public Health and Hygiene (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1920), 114, The Historical Medical Library, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

- 15. Park, Schroder, and Zingher, “The Control of Diphtheria,” 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Ibid.

- 17. Charles F. Bolduan, “Public Health Education,” in ed. William H. Park, Public Health and Hygiene (Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger, 1920), 740, The Historical Medical Library, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

- 18. Emphasis is mine. Park, Schroder, and Zingher, “The Control of Diphtheria,” 26–27.

- 19. The Schick test was a way of determining whether a child had natural immunity to diphtheria. Park used this test to determine whether he should give a child the experimental toxin–antitoxin.

- 20.Emphasis is mine “Warning Issued Against Menace of Schick Test,” The Christian Science Monitor 16, 1922. November , 5 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Park hoped that through participation in the trial, parents would be more inclined to bring their younger, at-risk children to future immunization campaigns: Park, Schroder, and Zingher, “The Control of Diphtheria,” 26–27.

- 22. The consent form states, “We are now reasonably certain that we know how to protect your child against the disease, IF YOU WILL HELP.” The capitalized last four words highlight the responsibility Park and the departments of health and education placed on parents to submit their children to the test. It is quite possible that parents were as a result unclear as to the experimental nature of the trial: Park, “Prevention of Individual Infectious Diseases,” 114.

- 23. Jeffrey P. Baker, “Immunization and the American Way: 4 Childhood Vaccines,” American Journal of Public Health 90, no. 2 (2000): 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24. The story of polio in the United States is well told; see David M. Oshinksy, Polio: An American Story (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005); John Rodman Paul, A History of Poliomyelitis (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1978); Jane S. Smith, Patenting the Sun: Polio and the Salk Vaccine (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990); and Daniel J. Wilson, Living With Polio: The Epidemic and Its Survivors (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2005). As these accounts describe, like in the diphtheria and measles vaccine trials, Salk had already tested his experimental vaccine in multiple smaller-scale trials. These involved institutionalized populations.

- 25. Several articles diverged from National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis’s official stance that the experiment was testing the vaccine’s efficacy, claiming that the vaccine’s efficacy had already been proven. For example, an article published in Better Homes and Gardens in 1954 asserts: “The Salk triple vaccine... has proved safe and effective against all three strains in some 5,000 preliminary tests”: Henry Lee, “No More Polio After ’54?” Better Homes and Gardens 32, no. 3 (March, 1954): 38. Similarly, an article published in School Life states that the vaccine “has already been tested for safety and effectiveness, first in studies with laboratory animals and then with nearly 700 individuals”: Hart E. Van Riper, “Polio Vaccine Tests in the Schools: In the Hope of Ending Polio,” School Life 36, no. 5 (1954): 69–70. Oddly, though, the same article contradicts this assertion, conceding, “Whether the vaccine is highly effective, moderately effective, or ineffective will be proved conclusively through the forthcoming mass tests with children.”.

- 26. While information sessions existed for parents to learn more about the trial, these were public as well, as opposed to a private discussion with a physician.

- 27. For concerns other vaccine researchers, such as Albert Sabin, had with the polio trial, see Harry M. Marks, “The 1954 Salk Poliomyelitis Vaccine Field Trial,” Clinical Trials 8 (2011): 224–234: 225; and Paul Meier, “Safety Testing of Poliomyelitis Vaccine,” Science 125, no. 3257(1957): 1067–1071.

- 28. E. Grant Youmans, “Parental Reactions to Communications on the 1954 Polio Vaccine Tests,” Rural Sociology 23 (1958): 383.

- 29.The study found that 41% of mothers who gave consent had discussed the trial with a doctor or nurse; 61% had discussed the trial with friends, relatives, or neighbors; 15% had discussed the trial with school personnel; and 28% had discussed it with no one: John A. Clausen, Morton A. Seidenfeld, and Leila C. Deasy, “Parent Attitudes Toward Participation of Their Children in Polio Vaccine Trials,”. American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/ajph.44.12.1526. 44 (1954): 1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. See Smith, Patenting the Sun, 267.

- 31. Ibid., 162–163.

- 32. Sarah Marie Lambert and Howard Markel, “Making History: Thomas Francis, Jr, MD, and the 1954 Salk Poliomyelitis Vaccine Field Trial,” Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine 154 (2000): 515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33. “Proposed Measles Vaccine Study: St. Joseph, Missouri,” 2, Box 17, Folder 3, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials Conferences Miscellaneous, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 34. “Measles Vaccine Studies,” December 8, 1959, Box 16, Folder 1, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials Articles. 1949, 1953–1960, 1 of 5, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 35. “Proposed Measles Vaccine Study: St. Joseph, Missouri,” 2.

- 36. Fred R. McCrumb Jr. to G. L. Blackwell, St Joseph, Missouri, July 5, 1960, Box 17, Folder 6, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials, General Correspondence. 1958–1960, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 37. Fred R. McCrumb to Dr Huntington Williams, Baltimore, Maryland, March 24, 1961, Box 17, Folder 7, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials, General Correspondence. 1961–1962, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 38. Letter to parents of Penn Wynne School, October 17, 1961, Series VI. Diseases and Treatment, Box 218, Folder “Measles #45 – 1961 Aug-1969,” Joseph Stokes Jr. Papers, American Philosophical Society.

- 39. David Paul, “Measles Vaccine: From the Children of America, for the World,” America Illustrated: U.S. Information Agency Russian-Language Magazine, Box 16, Folder 5, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials Articles 1961, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 40. Huntington Williams to Fred R. McCrumb, Baltimore, Maryland, March 30, 1961, Box 17, Folder 7, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials, General Correspondence. 1961–1962, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 41. While McCrumb used schools in his trials for the rubella, or German measles, vaccine and the mumps vaccine, both carried out in the late 1960s, vaccines developed more contemporarily have not used schools. In clinical trials of a varicella (chickenpox) vaccine conducted in 1984, the majority of children were recruited from private pediatric practices. A few children were enrolled from parochial schools and one day-care center: R. E. Weibel et al., “Live Attenuated Varicella Virus Vaccine. Efficacy Trial in Healthy Children,” New England Journal of Medicine 310, no. 22 (1984): 1409–1415. In clinical trials of an HPV vaccine conducted in 2004, young women were recruited through advertisements: D. M. Harper et al., “Efficacy of a Bivalent L1 Virus-like Particle Vaccine in Prevention of Infection with Human Papillomavirus Types 16 and 18 in Young Women: A Randomised Controlled Trial,” Lancet 364, no. 9447(2004): 1757–1765. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Elaine Tyler May Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era New York, NY:Basic Books; 198817 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Measles was seen as so ubiquitous, and its symptoms rarely dangerous, that becoming infected was just an inevitability of childhood. As one 1962 article states, “Measles has always been accepted as part of the growing-up process, as much a part of childhood as stubbed toes and dirty hands”: J. D. Ratcliff, “Goodbye Measles! New Vaccine—Which Experts Say Will Be Available This Year—Promises an End to This Often Serious Childhood Disease,” Parents’ Magazine & Better Homemaking 37, no. 1 (January 1962): 56. Also see Elena Conis, Vaccine Nation: America’s Changing Relationship With Immunization (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 52.

- 44.See David J. Rothman Strangers at the Bedside: A History of How Law and Bioethics Transformed Medical Decision Making New York, NY: Basic Books; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 45. “Measles Vaccine Studies,” December 8, 1959, Box 16, Folder 1, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials Articles. 1949, 1953–1960, 1 of 5, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 46. “Questionnaire Concerning Research Projects Involving Human Beings as Volunteers,” Box 17, Folder 9, University of Maryland School of Medicine Rubella (German Measles) Vaccine Field Trials General Correspondence. Jul 1963–Apr 1970, Fred R. McCrumb Papers, Library of Congress.

- 47.The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research Washington, DC:Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ibid., emphasis is mine.

- 49.Christine Grady, “Enduring and Emerging Challenges of Informed Consent,”. New England Journal of Medicine. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1411250. 372 (2015): 856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]