CycloSPORINE Dispensing Errors

Almost 20 years ago (ISMP Medication Safety Alert! September 9, 1998), we published an article about SANDIMMUNE (cycloSPORINE capsules and oral solution) and how this nonmodified form of the drug has decreased bioavailability compared with NEORAL or GENGRAF (cycloSPORINE [MODIFIED] capsules and oral solution). At the time, a survey by Novartis identified that 24% of prescriptions failed to specify which form of the drug should be dispensed, and only 22% of these prescriptions were clarified. We mention this because, 20 years later, we are still receiving reports of patients receiving SandIMMUNE when the prescriber’s preference was for a cycloSPORINE-modified oral formulation. Three patients recently received SandIMMUNE instead of the more appropriate form of the drug, Neoral or Gengraf. In another case, during medication reconciliation, a nurse documented that a hospitalized patient was taking cycloSPORINE but did not verify the brand name to determine whether it was the modified or regular form of the drug. The patient’s physician prescribed SandIMMUNE, and the patient received a dose before a pharmacy technician discovered that the patient had recently filled a prescription for Gengraf.

Because of the difference in formulation, these products are not interchangeable. Blood levels must be monitored to prevent serious consequences if a transplant patient receives the wrong formulation. Prescribers should indicate the brand name, and pharmacists should clarify prescriptions for cycloSPORINE. Order entry systems should clearly display these different forms of the drug, and a hard stop should force verification of the correct drug form during prescribing.

CycloSPORINE Oral Solution Error

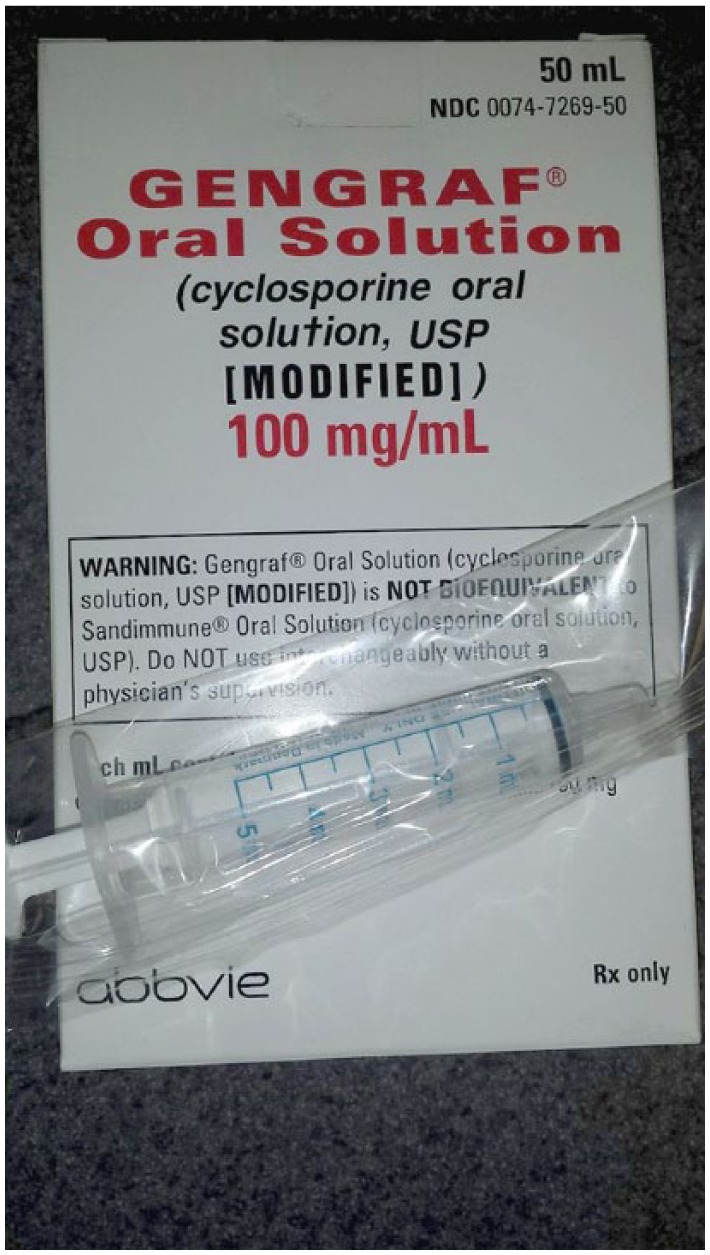

A 10-fold overdose of modified cycloSPORINE oral solution (100 mg/mL) was administered to a child. The physician prescribed 0.5 mL (50 mg), and the pharmacy dispensed a sealed package of the medication (100 mg/mL), which contained a 5 mL oral syringe (Figure 1) provided by the manufacturer, AbbVie, that was calibrated in 1 mL increments, with hash marks between each mL. The child’s parent gave 5 mL (500 mg) instead of 0.5 mL to the child for several days.

Figure 1.

A 5 mL syringe accompanies Gengraf brand of cyclosporine oral solution modified.

Patients who received solid organ transplant or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants are required to take long-term immunosuppressant drugs to prevent rejection and graft-vs-host disease. The dosages of immunosuppressants are usually individualized based on the type of transplant, target blood level, body weight, drug-drug interactions, and the risk of rejection or toxicity. Many transplant centers use oral solution formulations of immunosuppressant agents to allow greater flexibility in dosage adjustments, especially for pediatric patients. As immunosuppressant agents have significant interpatient dosing variability, dosage delivery devices need to be selected specifically for each patient, and one size does not fit all. In this case, the 5 mL syringe size was significantly larger than each intended dose and did not facilitate accurate measurement and delivery of the prescribed dose.

Upon product dispensing, pharmacists should evaluate the appropriateness of the dosage delivery devices included in the package. A 2016 study1 found that parents made fewer errors when measuring oral liquid medications for their children with oral syringes compared with dosing cups. However, the error rate with using oral syringes was still 16.7%. The researchers also found that providing dosing devices that closely matched the prescribed volume per dose offered the greatest reduction of errors.2 Health care professionals should ask patients/caregivers to show them how they will properly measure oral liquid medications using their dosage delivery device. (If the pharmacy that dispensed the cycloSPORINE had done this, the dosing error might have been avoided.) The manufacturer and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were notified about this event, and a recommendation was made to investigate including a smaller syringe for pediatric patients in the package.

Patients Should Not Swallow AcipHex Sprinkle Capsules!

ACIPHEX SPRINKLE (RABEprazole sodium) delayed-release capsules are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease in children 1 to 11 years for up to 12 weeks. Although the product is a capsule, it must not be swallowed whole or chewed, nor should the granules be crushed. AcipHex delayed-release tablets for adults should be swallowed whole, not crushed or chewed. But for the sprinkles, patients or caregivers should open the capsule and sprinkle the granule contents on a spoonful of soft food or liquid, and take the entire mixture within 15 minutes of preparation. AcipHex Sprinkle is the only capsule formulation proton pump inhibitor (PPI) that cannot be swallowed whole. All other PPI capsules, such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, and lansoprazole, can be swallowed whole, although patients who have difficulty swallowing can also open these capsules and sprinkle the pellets over a tablespoon of applesauce. Other sprinkle capsules, such as topiramate sprinkle capsules, divalproex sodium delayed-release sprinkle capsules, and KLOR-CON sprinkle capsules (potassium chloride extended-release), can be swallowed whole or opened and sprinkled over soft food.

Unfortunately, some of the auxiliary labels that automatically print along with pharmacy labels for AcipHex Sprinkle capsules may be interpreted to mean that the capsules can be swallowed whole. If applied to the prescription bottle, the labels can cause confusion and increase the risk of incorrect administration if older children try to swallow the capsules.

ISMP contacted the manufacturer’s medical information group, and the company could not comment on the clinical and safety outcomes if patients swallow the AcipHex Sprinkle capsule whole. Retail pharmacies should evaluate the medical information pamphlet and auxiliary labels programmed to print with AcipHex Sprinkle prescriptions to be sure they reflect the correct administration method. Hospital pharmacies also need to make nurses aware of the correct administration either through built-in administration instructions in the electronic medical record or other drug information resources. We also contacted all major drug information vendors so they can make any necessary changes to auxiliary warnings they provide in their content for pharmacies.

Differentiating Insulin Types by Touch and Separate Storage

A pharmacist told us about an insulin mix-up that her visually impaired mother-in-law experienced. Her mother-in-law uses insulin pens for both rapid-acting (insulin lispro) and long-acting (insulin glargine) insulins at home. She stores them together although she administers the rapid-acting insulin 3 times a day with meals and the long-acting insulin at night. On 2 occasions, she has accidentally given herself 50 units of the rapid-acting insulin instead of the long-acting insulin at night. Although 50 units is the correct dose for her long-acting insulin, it is a very large dose of the rapid-acting insulin given all at once. Both times, the pharmacist’s mother-in-law recognized her mistake and had to stay up until early in the morning drinking juice and checking her blood glucose levels frequently. The pharmacist happened to be visiting the last time it happened. Despite readings of about 100 mg/dL about 2 hours after the mistake, her mother-in-law still woke up (fortunately) at 4 a.m. with a low blood glucose value of 50 mg/dL.

After the first incident, the pharmacist and her mother-in-law talked about separating the 2 pens to prevent accidental mix-ups, but for logistical reasons, this would have been challenging. She has now wrapped a hair tie around the long-acting insulin pen so it “feels” different to her. While reading the label each time is important, patients with diabetes who have vision problems may have difficulty seeing the labels or stickers well.

Many years ago, various types of rapid-acting, intermediate-acting, and long-acting insulins were packaged in vials that were different from one another in shape (round, square, one with a hexagonal neck) to help patients with sight and touch issues differentiate the products. This is no longer true with vials, all of which are round, and pens are all similarly shaped.

To help prevent mix-ups, teach patients that using adhesive tape, a rubber band, or in this case, hair ties may be a good way to help differentiate different insulin types. Perhaps storing the medicines in containers with prominent “long-acting” and “rapid-acting” stickers on the containers could also help differentiate the products. As insulin does not need to be kept in the refrigerator once it has been opened, it may also be helpful to instruct patients to keep their long-acting, bedtime insulin pen in the bedroom, and their rapid-acting, mealtime insulin pen in the kitchen or dining room. However, relying totally on where a medicine is stored is risky and can lead to an error, especially if a spouse moves the insulin around.

Look-Alike Name Pair—VoLumen and Voluven

An obstetrical patient received oral VOLUMEN (barium sulfate suspension, E-Z-EM [subsidiary of Bracco]) instead of intravenous (IV) fluid resuscitation with VOLUVEN (tetrastarch, hydroxyethyl starch in sodium chloride injection, Hospira). One might assume that such an error must be next to impossible given the different routes of administration, the typical dose of oral barium sulfate, and the fact that imaging of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract had not been ordered. However, here is how the error happened.

In deciding what to order for fluid resuscitation, the patient’s obstetrician consulted with a certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA) who recommended Voluven. The obstetrician then typed “V-O-L-U” in the computer order entry system, and VoLumen popped up. Subsequently, 500 mL of VoLumen was ordered instead of the intended Voluven. A hospital pharmacist soon called the prescriber to confirm the odd request, but the prescriber insisted that the drug was what the CRNA told him to order. The pharmacist then called the CRNA on call, but due to a language barrier and unfamiliarity with VoLumen, the CRNA thought the pharmacist was asking about Voluven and stated that it was fine to use this medication. The patient received the entire 500 mL of oral barium (orally) and fortunately suffered no adverse effects other than delaying her overall care.

When clarifying orders, encourage practitioners to use a standard format that helps to ensure clarity of communication (eg, SBAR), which includes an assessment of the concern. In this case, asking whether the patient was scheduled for GI imaging might have clarified the issue with the prescriber and the CRNA. The hospital added these medications to its look-alike, sound-alike drug name list and made modifications in the electronic prescribing system to alert providers when one or the other is ordered. ISMP has contacted each manufacturer as well as the US FDA to consider the need for a name change for one of these products.

Severe Under Dosing of Insulin With U-500 Pen

An emergency department (ED) pharmacist was talking to a patient about his U-500 insulin dose. The patient, who had been using a U-500 insulin pen, told the pharmacist that his dose was 75 units but proceeded to show the pharmacist how he turned the dose knob on the pen to “15” to deliver each dose. The patient thought his physician had told him to dial to “15” to deliver 75 units. Prior to using the U-500 pen, the patient used a U-100 syringe to measure each dose of 75 units from a vial of U-500 insulin. Before U-500 syringes or pens were available, patients using U-500 insulin were commonly taught to use a U-100 insulin syringe and to measure their dose in “syringe units,” meaning the U-100 scale was used for dose measurement, but the actual dose was 5 times more than the measured dose. Thus, the patient had been drawing up the U-500 insulin into the U-100 syringe to the “15” units marking. The patient was then shown how to deliver the correct dose by dialing the U-500 insulin pen to 75 units.

Even with the availability of U-500 insulin pens, patient and provider confusion about the dose may still occur, especially when patients previously relied on a U-100 syringe to inject U-500 insulin. Dangerous under dosing with a U-500 pen should be considered in patients who exhibit severe hyperglycemia or diabetic ketoacidosis. For U-500 insulin, ISMP recommends using a U-500 insulin pen or a U-500 insulin syringe. Unfortunately, patients still use U-100 syringes with U-500 insulin, thus risking confusion.

References

- 1. Yin HS, Parker RM, Sanders LM, et al. Liquid medication errors and dosing tools: a randomized controlled experiment. Pediatrics. 2016;138:e20160357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yin HS, Parker RM, Sanders LM, et al. Pictograms, units and dosing tools, and parent medication errors: a randomized study. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20163237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]