Abstract

Introduction

Ophthalmic segment aneurysms may present with visual symptoms due to direct compression of the optic nerve. Treatment of these aneurysms with the Pipeline embolization device (PED) often results in visual improvement. Flow diversion, however, has also been associated with occlusion of the ophthalmic artery and visual deficits in a small subset of cases.

Case report

A 49-year-old Caucasian female presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. On follow-up imaging, the patient was found to have a right asymptomatic ophthalmic segment aneurysm. Due to the irregular shape of the aneurysm and history of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, the decision was made to treat the aneurysm with a PED. Postoperatively, the patient complained of floaters in the right eye. Detailed ophthalmologic examination showed retinal hemorrhage and cotton-wool spots on the macula. Such complication after PED placement has never been reported in the literature.

Conclusion

Visual complications after PED placement for treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms are rare. It is thought that even in cases where the ophthalmic artery occludes, patients remain asymptomatic due to the rich collateral supply from the external carotid artery branches. Here we report a patient who developed an acute retinal hemorrhage after PED placement.

Keywords: Pipeline, flow diversion, visual, complications, retinal, hemorrhage

Introduction

Despite the low risk of rupture in ophthalmic segment aneurysms (OSAs), treatment is indicated in the presence of visual symptoms, or if the aneurysm features confer a high risk of rupture, such as large size, growth and shape irregularity.1 Since the Pipeline embolization device (PED) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011, several studies have reported its safety and efficacy in treatment of OSAs. Complete occlusion rates are high (77–82%) with low rate of complications (2–7%) and need for retreatment (0–7%).2–6 The rate of ophthalmic artery occlusion after PED varies widely with some authors reporting occlusion in up to 25% of cases with patients frequently remaining asymptomatic due to the rich collateral supply from the external carotid artery branches.7

Here we report a patient who presented with an acute retinal hemorrhage after PED placement for treatment of an OSA. To our knowledge, such a case has never been reported in the literature.

Case report

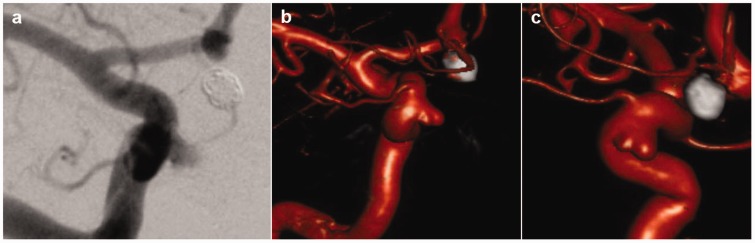

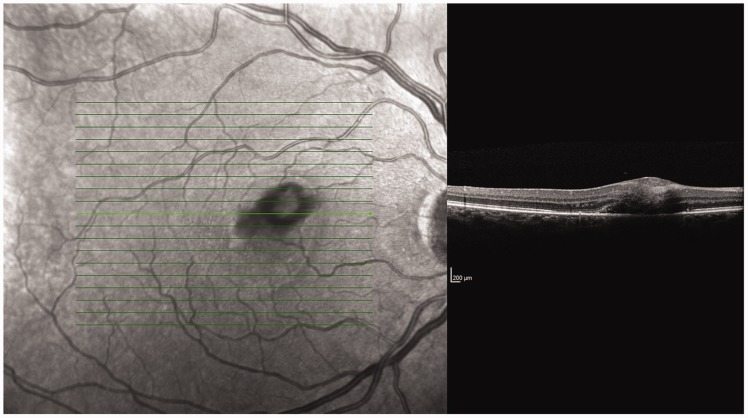

A 49-year-old Caucasian female with no significant past medical history of any systemic or known retinal vascular disease presented with a subarachnoid hemorrhage due to a ruptured anterior communicating artery aneurysm. The aneurysm was treated by endovascular coil embolization with complete obliteration, and the patient made a full recovery with no residual neurologic symptoms. During the same procedure, a small right OSA was incidentally found, measuring 2.1 mm × 2 mm with a 2.5 mm neck. On the 2-month follow-up, the patient was started on 325 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel to prepare for a stent-assisted coiling. On the 4-month follow-up, digital subtraction angiography showed aneurysmal growth, now measuring 5.5 mm × 3.5 mm with a 5 mm neck, and a 4 mm daughter sac (Figure 1). Due to the irregular shape and growth of the aneurysm and history of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, the aneurysm was treated with a PED without intraprocedural complications. On the following day, the patient started complaining of new onset floaters in the right eye. On ophthalmologic examination, there were no deficits in visual field or acuity. The retina showed multiple variably sized hemorrhages in the periphery of the right eye, and an abnormal foveal light reflex with yellow-white retinal infiltrates in the macula, representing cotton-wool spots (Figure 2). The patient was discharged on the same day and was referred to a retina specialist. On the 5-month follow-up, the patient was still suffering from visual symptoms that progressed clinically into central scotoma, but with no further retinal changes.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior digital subtraction angiography (a) and dual-volume three-dimensional reconstruction (b–c) of a right internal carotid artery injection showing an ophthalmic segment aneurysm with irregular shape.

Figure 2.

Acute retinal hemorrhage after Pipeline embolization device placement.

Discussion

Here we report a patient with an incidental OSA who developed acute retinal hemorrhage after PED placement. The patient was on a high-dose aspirin (325 mg) and clopidogrel (75 mg) for 2 months. Skukalek et al. reported transient and symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (either subarachnoid or intraparenchymal) after PED placement in 4.7% of patients who are placed on high-dose aspirin for 6 months or less.8 Nonetheless, retinal hemorrhage has not been reported. Whether this complication was due to antiplatelet treatment, microvasculature rupture or both is unknown, and causal relationship could not be established. However, it should be recognized as a possible complication after PED use in the treatment of OSAs.

PED in treatment of OSAs

In 2011, the PED was approved for the endovascular treatment of adults with large or giant wide-necked intracranial aneurysms affecting the internal carotid artery from the petrous to the superior hypophyseal segment.9 The device diverts the blood flow away from the aneurysm and provides a scaffold for endothelial cells to grow leading to obliteration of the aneurysm and preservation of the side branches.9

Lanzino et al. reported on the efficacy of PED as compared to assisted or unassisted coil embolization in treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Mean size was 14.9 ± 6.3 mm in the PED group and 13.9 ± 6.7 mm in the coiling group. They found a significantly higher rate of complete occlusion in PED patients (76%) as compared to coiled patients (21%).4 Similar results were reported by Chalouhi et al. for large and giant paraclinoid aneurysms (86% versus 14%). Mean size was 14.9 ± 4.7 mm in the PED group and 14.9 ± 5.9 mm in the coiling group. The rate of retreatment was considerably lower with PED (2.8% versus 37%) and complication rates were comparable (7.5% in both groups).2 Adeeb et al., on the other hand reported comparable outcomes between PED and stent-assisted coiling in treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms.10

Visual outcomes

Visual outcome and patency of the ophthalmic artery is a major concern in the treatment of OSAs with PED. The ophthalmic artery has a rich collateral supply from the branches of the external carotid artery. The extent of the collateral supply appears to determine the tendency for ophthalmic artery occlusion.7,11 Puffer et al. reported that approximately one-quarter of patients with OSAs who underwent PED placement will occlude the ophthalmic artery eventually.7 Nevertheless, this was well tolerated clinically and no patients experienced visual deficits.7 However, only five patients had a thorough ophthalmologic examination, and visual field defects due to ischemic lesions can easily go undiagnosed. Rouchaud et al. reported immediate ophthalmic artery occlusion in 14.3% of patients who underwent PED placement for treatment of OSAs (mean size 8 mm, range 3–17 mm).11 This occurred predominantly in cases where the ophthalmic artery originated from the inner curve of the carotid siphon, followed by ophthalmic artery origin from the neck of the aneurysm. Six patients (21.4%) developed visual blurring and four (14.3%) had visual field defects after treatment. Two cases of the visual field defects were asymptomatic and only detected on the complete ophthalmologic examination. Griessenauer et al. found that the ophthalmic artery remained patent in 96.8% of patients with small OSAs (≤7 mm) at last follow-up after PED placement.3 In contrast to the aforementioned study, they found that patients with ophthalmic artery arising from the aneurysm dome tend to have a lower ophthalmic artery patency rate. This observation, however, did not reach statistical significance.

Zanaty et al. reported a series of 41 patients with 44 OSAs (mean size 12.61 ± 8.4 mm) who underwent PED placement.6 Among patients who presented with visual symptoms, complete resolution was achieved in 73%, and worsening of symptoms was noted in one patient (4.5%). In their analysis of the Pipeline for Uncoilable or Failed Aneurysms (PUFS) trial (mean size 14.7 mm ± 5.6 mm), Sahlein et al. reported only one patient with a new onset visual field deficit after PED placement, due to a thromboembolic occlusion of the central retinal artery.5

Conclusion

OSAs are associated with low rupture rates, but large and giant aneurysms may lead to visual symptoms due to the direct mass effect. The use of PED in the treatment of these aneurysms has been associated with high occlusion rates and significant clinical improvement. Despite occlusion of the ophthalmic artery in some cases, visual complications are rare. Here we present a patient who suffered from an acute retinal hemorrhage after PED placement for the treatment of OSAs.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gross BA, Du R. Microsurgical treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20: 1145–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalouhi N, Tjoumakaris S, Starke RM, et al. Comparison of flow diversion and coiling in large unruptured intracranial saccular aneurysms. Stroke 2013; 44: 2150–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griessenauer CJ, Ogilvy CS, Foreman PM, et al. Pipeline embolization device for small paraophthalmic artery aneurysms with an emphasis on the anatomical relationship of ophthalmic artery origin and aneurysm. J Neurosurg 2016; 125: 1352–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanzino G, Crobeddu E, Cloft HJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of flow diversion for paraclinoid aneurysms: a matched-pair analysis compared with standard endovascular approaches. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 2158–2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sahlein DH, Fouladvand M, Becske T, et al. Neuroophthalmological outcomes associated with use of the pipeline embolization device: analysis of the PUFS trial results. J Neurosurg 2015; 123: 897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanaty M, Chalouhi N, Barros G, et al. Flow-diversion for ophthalmic segment aneurysms. Neurosurgery 2015; 76: 286–289. discussion 289–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puffer RC, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ, et al. Patency of the ophthalmic artery after flow diversion treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2012; 116: 892–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skukalek SL, Winkler AM, Kang J, et al. Effect of antiplatelet therapy and platelet function testing on hemorrhagic and thrombotic complications in patients with cerebral aneurysms treated with the pipeline embolization device: a review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg 2016; 8: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishna C, Sonig A, Natarajan SK, et al. The expanding realm of endovascular neurosurgery: flow diversion for cerebral aneurysm management. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc J 2014; 10: 214–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adeeb N, Griessenauer CJ, Foreman PM, et al. Comparison of stent-assisted coil embolization and pipeline embolization device for endovascular treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms: a multicenter cohort study. World Neurosurg 2017; 105: 206–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouchaud A, Leclerc O, Benayoun Y, et al. Visual outcomes with flow-diverter stents covering the ophthalmic artery for treatment of internal carotid artery aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 330–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]