At this time in our global history, when immigration policies are under frequent review, an understanding of the health status of immigrants has become increasingly important. In this issue of the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Perl et al.1 provide the first comprehensive report of the epidemiology of dialysis-dependent ESRD (ESRD-D) among immigrants compared with long-term residents. They conducted their study in Ontario, Canada, where universal health care coverage, including maintenance dialysis, begins shortly after an immigrant arrives. The authors found that the prevalence and incidence of ESRD-D differed significantly by world region and country of birth, with immigrants to Canada who were from sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean having the highest ESRD-D risk. To understand how best to address these risk differences, careful consideration of exactly why certain immigrant groups might have a greater burden of ESRD-D is imperative—or to state it in Swahili, kwa nini?

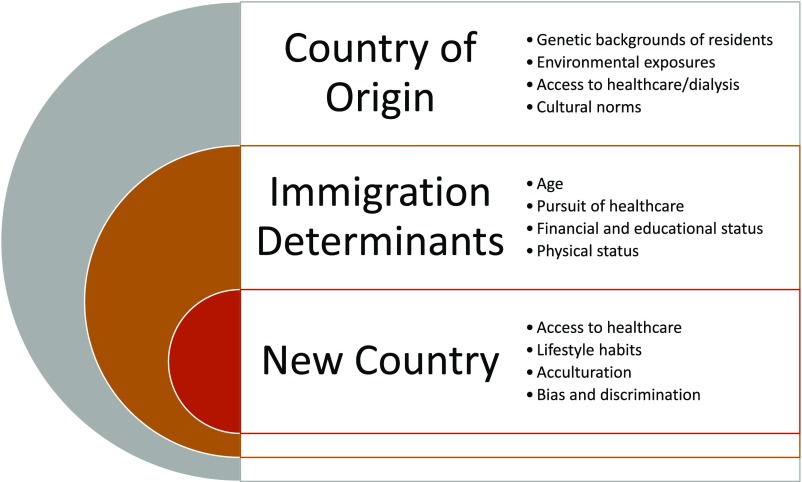

The factors influencing the risk of ESRD-D among immigrants likely include those related to the country of origin, the influences that informed the decision to immigrate, and the new country itself (Figure 1). Perl et al.1 found the greatest prevalence of ESRD-D to be among immigrants from countries likely to have high prevalence of APOL1 risk variants2 given their predominant African ancestry. If this was the primary driver of greater risk of ESRD-D for these individuals, one might expect their kidney failure rates to mirror those seen in their country of origin. Unfortunately, for many low- and middle-income countries (including several in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean), data on ESRD prevalence are limited, and dialysis is not widely accessible. Thus, estimates of ESRD-D are incomparable with what might be seen in countries with broader availability of dialysis. For example, Perl et al.1 found a prevalence of ESRD-D of 159.2 per 100,000 population for immigrants from Sudan, but in 2015, only 20 per 100,000 population were treated with hemodialysis in Sudan.3

Figure 1.

Potential factors influencing dialysis-dependent ESRD risk among immigrants might include those related to the country of origin, those that influenced the decision and ability to immigrate, and the new country.

If genetic risk was the key explanatory factor for the differences in ESRD-D in Ontario, it would also be expected that long-term Canadian residents with similar ancestry or race/ethnicity as a proxy would have comparable rates of ESRD-D. Perl et al.1 note that a limitation of their study was the lack of data on race/ethnicity among long-term Canadians to allow for this comparison.

The motivation for immigration and the ability to immigrate may each play an important role in determining ESRD-D risk among immigrants. Younger, more physically robust individuals may be more likely to pursue moving to another country than older and/or frail persons. Consistent with this, Perl et al.1 found a 4.6-year (31%) difference in mean age between immigrants and long-term residents with ESRD-D. Socioeconomic status is also likely a strong determinant of ability to immigrate. Perl et al.1 found that immigrants from Somalia, designated by the United Nations to be a least developed country,4 had the highest prevalence and the second highest incidence of ESRD-D. Although many immigrants from least developed countries, such as Somalia, may have very low incomes, they may be more financially stable than others in their country of origin, leading to their opportunity for mobility. Notably, the average age of immigrants with ESRD-D in Ontario was 62.4 years old, which is >7 years older than the average life expectancy for Somalis in Somalia, who, on average, live to only 55 years old.5

Because of limited access to dialysis in many low- and middle-income countries, individuals who are able may move to a new country in pursuit of long-term care of their kidney disease. For those able to pass the immigration process (including screening for communicable diseases and demonstration of value to the workforce), moving to countries such as Canada, where universal health care is available, would be attractive. Therefore, populations of immigrants with prevalent ESRD-D might be enriched with individuals with relatively better overall health than long-term residents with ESRD-D due to the “healthy immigrant effect.”6 Whether this leads to immigrants’ better survival on dialysis is worthy of further study.7

The incident ESRD-D findings by Perl et al.1 argue that factors related to similarities and differences between the country of origin and the country immigrated to affected risk of ESRD-D. Compared with persons who immigrated to Ontario from Western nations, immigrants from East Asia, South Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and sub-Saharan Africa had higher incidence of ESRD-D, particularly among those who had lived in Canada for at least 10 years. Immigrants from these countries may have adopted Western dietary8 and other habits that negatively affected their kidney health. Similar to what has been observed for several other socially marginalized groups, these immigrants also may have encountered bias in health care9 and other settings that can affect kidney outcomes.

The potential underlying causes are numerous, but the disparities in ESRD-D documented by Perl et al.1 certainly warrant attention and efforts to mitigate them. Early identification of immigrants at high risk for ESRD could allow for timely interventions, including referral to nephrology and the start of renoprotective medications. Some programs aimed at meeting the needs of immigrants with other chronic conditions have included the use of community health workers to deliver educational interventions.10 Tailored approaches specifically targeting individuals with risk factors for CKD progression are needed that are both accessible and acceptable among immigrant groups.

Disclosures

None.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related article, “ESRD among Immigrants to Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Study,” on pages 1948–1959.

References

- 1.Perl J, McArthur E, Tan VS, Nash DM, Garg AX, Harel Z, et al. : ESRD among immigrants to Ontario, Canada: A population-based study. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 1948–1959, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, Astor BC, Li M, Hsu CY, et al. ; AASK Study Investigators; CRIC Study Investigators: APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 369: 2183–2196, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naicker S, Ashuntantang G: End stage renal disease in sub-Saharan Africa. In: Chronic Kidney Disease in Disadvantaged Populations, Vol. 1, edited by Garcia-Garcia G, Agoda LY, Norris KC, London, Academic Press, 2017, pp 125–137 [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Criteria for Identification of Least Developed Countries, 2015. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category/ldc-criteria.html. Accessed May 12, 2018

- 5.World Health Organization: Somalia: Life Expectancy, 2015. Available at: http://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/somalia-life-expectancy. Accessed May 12, 2018

- 6.Vang ZM, Sigouin J, Flenon A, Gagnon A: Are immigrants healthier than native-born Canadians? A systematic review of the healthy immigrant effect in Canada. Ethn Health 22: 209–241, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Beukel TO, Dekker FW, Siegert CE: Increased survival of immigrant compared to native dialysis patients in an urban setting in the Netherlands. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 3571–3577, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanou D, O’Reilly E, Ngnie-Teta I, Batal M, Mondain N, Andrew C, et al. : Acculturation and nutritional health of immigrants in Canada: A scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health 16: 24–34, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, Beach MC, Sabin JA, Greenwald AG, et al. : The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health 102: 979–987, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Taher MD, Riley L, Tandon SD, Tanner M, et al. : A culturally tailored community health worker intervention leads to improvement in patient-centered outcomes for immigrant patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Diabetes 36: 100–111, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]