Abstract

Background and Purpose

Stereoacuity measurement is a common element of pediatric ophthalmic examinations. Although the Stereo Fly Test is routinely used to establish the presence of coarse stereopsis (3000 arcsecs), it often yields a false negative “pass” due to learned responses and non-stereoscopic cues. We developed and evaluated a modified Stereo Fly Test protocol aimed at increasing sensitivity, thus reducing false negatives.

Patients and Methods

The Stereo Fly Test was administered according to manufacturer instructions to 321 children aged 3–12 years. Children with a “pass” outcome (n = 147) were re-tested wearing glasses fitted with polarizers of matching orientation for both eyes to verify that they were responding to stereoscopic cues (modified protocol). The response to the standard Stereo Fly Test was considered a false negative (pass) if the child still pinched above the plate after disparity cues were eliminated. Randot® Preschool Stereoacuity and Butterfly Tests were used as gold standards.

Results and Conclusions

Sensitivity was 81% (95% CI: 0.75 – 0.86) for standard administration of the Stereo Fly Test (19% false negative “pass”). The modified protocol increased sensitivity to 90% (95% CI: 0.85 – 0.94). The modified two-step protocol is a simple and convenient way to administer the Stereo Fly Test with increased sensitivity in a clinical setting.

Keywords: stereoacuity, strabismus, anisometropia, amblyopia

INTRODUCTION

Measurement of stereoacuity is a common element of pediatric ophthalmic examinations. Random-dot stereograms are widely used to examine pediatric patients with eye conditions that may disrupt binocular vision. One limitation of the many graded contour and random-dot stereoacuity tests available for clinical use is that the largest disparity is 400–800 arcsecs.1–3 As a result, the Stereo Fly Test is routinely used to determine the presence of coarse stereopsis (3000 arcsecs). Unfortunately, false negative “pass” outcomes are common with the Stereo Fly Test because the child: 1) knows it is a fly and expects the wings to be elevated; 2) has been repeatedly exposed to the same test with only two possible responses; or 3) alternates fixation and observes image jump in disparate portions of the test. Here, we present a modified administration of the Stereo Fly Test protocol designed to reduce false negative “pass” outcomes.1, 4–7

METHODS

Children aged 3–12 years treated for strabismus (n = 105), anisometropia (n = 67), strabismus and anisometropia (n = 74), congenital or developmental cataracts (n = 25), or retinopathy of prematurity (n = 13) were referred for participation in the study by sixteen Dallas-Fort Worth pediatric ophthalmologists. Normal control children (n = 37) with age-appropriate visual acuity and stereoacuity were also enrolled.

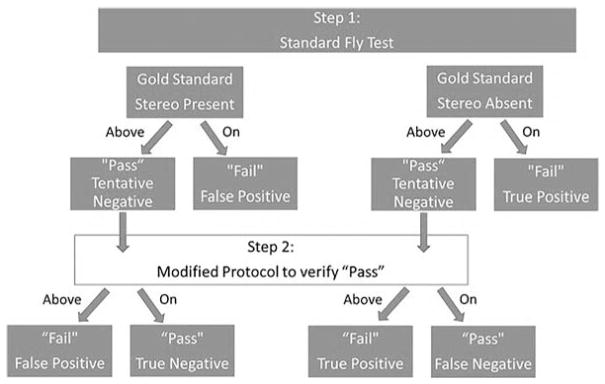

The Stereo Fly Test was administered according to the manufacturer instructions. Wearing standard 3-D polarized glasses (90° interocular orientation difference), the children were asked to “pinch the fly’s wings.” If a child touched the plate, this established their inability to appreciate the stereoscopic depth, and their outcome was “fail.” If the child pinched the wings above the plate, their outcome was considered a tentative “pass” and they were eligible to participate in the modified Stereo Fly Test protocol designed to verify a “pass” outcome, as described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for analysis of responses to Step 1 and Step 2 of Modified Protocol.

Modified Stereo Fly Test Protocol

To verify the tentative “pass” outcome, children who passed the initial administration of the Stereo Fly Test were re-tested wearing glasses with polarizers orientated in the same direction for both eyes to eliminate disparity cues. If the child still pinched above the plate with the modified glasses, their tentative “pass” outcome to the standard Stereo Fly Test administration was not verified—i.e., the “pass” outcome from the standard protocol was a false negative and the final outcome was “fail” (Figure 1). If the child touched the plate with the modified glasses, their tentative “pass” outcome for the standard Stereo Fly Test was verified—i.e., their final outcome was “pass.”

All children were also tested with the Randot® Preschool Stereoacuity Test and Stereo Butterfly Test, which served as gold standards.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas. All procedures and data collection were conducted in a manner compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and all research procedures adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

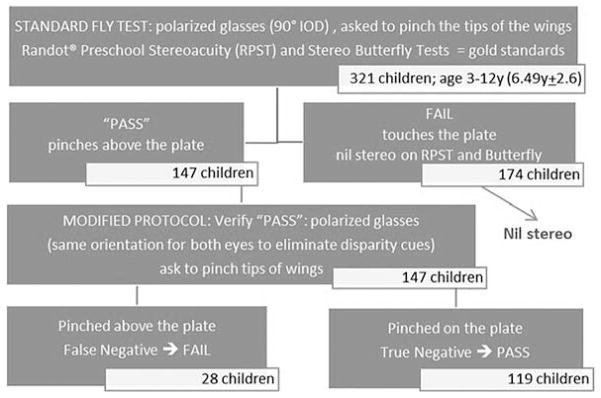

Results are summarized in Figure 2, from 321 children with a mean ± SD age of 6.49 ± 2.6 years who were enrolled in the study. Using the standard protocol for the Stereo Fly Test, 174 children touched the plate and were assigned a “fail” outcome. All 174 children who failed the standard protocol also scored nil on the Randot Preschool Stereoacuity Test and Stereo Butterfly Test and, therefore, were categorized as true positives. The remaining 147 children pinched the wings above the plate, and were assigned a tentative “pass” outcome for the Stereo Fly Test. The 147 children who passed were eligible to be tested with the modified Stereo Fly Test to verify their outcome; 119 touched the plate verifying their “pass” outcome. The remaining twenty-eight (19%) children pinched above the plate, so their tentative “pass” outcome for the Stereo Fly Test was considered a false negative—i.e., their “pass” outcome was not verified and their final outcome was changed to “fail.” For the standard administration of the Stereo Fly Test, sensitivity was 81% (95% CI: 0.75–0.86) yielding a 19% false negative “pass.” The modified protocol increased sensitivity to 90% (95% CI: 0.85–0.94), as shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart for testing with the Two-Step Modified Protocol.

TABLE.

MODIFIED STEREO FLY TEST PROTOCOL RESULTS COMPARED WITH THE GOLD STANDARD RANDOM DOT STEREOACUITY TEST RESULTS

| Children who “passed” the Stereo Fly Test (pinched wings above plate) | Random Dot Stereograms: Stereo Present | Random Dot Stereograms: Nil Stereo |

|---|---|---|

| Verifly Fly: Pinch ABOVE Plate | 9 | 193 |

| Verifly Fly: Pinch ON Plate | 98 | 21 |

DISCUSSION

Previous studies show that standard administration of the Fly Test yields 19–67% false negative “pass” results.4–7 Implementing the two-step protocol described here is simple and convenient, and the initial response can be verified without the child realizing any image differences (the elimination of disparity cues) made by changes such as turning the book or covering one eye. In addition, the modified protocol eliminates any cues that may arise from alternating fixation and image jump in disparate portions of the test. When random-dot stereoacuity is not present, assessment of coarse stereopsis with the Stereo Fly Test using our modified two-step protocol to verify the response provides a more accurate assessment of binocularity than the standard Stereo Fly Test protocol in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

This work received support from NEI grant number EY022313, Fight for Sight PD15002, Knights Templar Eye Foundation 16-2015-CS.

References

- 1.Birch EE, O’Conor AR. Taylor and Hoyt’s Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 5. London: Elsevier; 2016. Binocular vision. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fawcett SL, Birch EE. Validity of the Titmus and Randot circles tasks in children with known binocular vision disorders. J AAPOS. 2003;7:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fawcett SL, Birch EE. Interobserver test-retest reliability of the Randot preschool stereoacuity test. J AAPOS. 2000;4:354–358. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2000.110340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnoldi KA, Wilson ME, Saunders RA, Trivedi RH. Pediatric Ophthalmology: A Current Thought and Practical Guide. Chapter 10. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2009. Detecting and quantifying stereopsis; pp. 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Archer SM. Stereotest artifacts and the strabismus patient. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1988;226:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF02172957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arnoldi K, Frenkel A. Modification of the Titmus fly test to improve accuracy. Am Orthopt J. 2014;64:64–70. doi: 10.3368/aoj.64.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasche H, Gockeln R, de Decker W. The Titmus Fly Test—evaluation of subjective depth perception with a simple finger pointing trial: Clinical study of 73 patients and probands. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2001;218:38–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]