Abstract

Background

Randomized trials have shown increased risk of suicidality associated with efavirenz (EFV). The START (Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment) trial randomized treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive adults with high CD4 cell counts to immediate vs deferred antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Methods

The initial ART regimen was selected prior to randomization (prespecified). We compared the incidence of suicidal and self-injurious behaviours (suicidal behavior) between the immediate vs deferred ART groups using proportional hazards models, separately for those with EFV and other prespecified regimens, by intention to treat, and after censoring participants in the deferred arm at ART initiation.

Results

Of 4684 participants, 271 (5.8%) had a prior psychiatric diagnosis. EFV was prespecified for 3515 participants (75%), less often in those with psychiatric diagnoses (40%) than without (77%). While the overall intention-to-treat comparison showed no difference in suicidal behavior between arms (hazard ratio [HR], 1.07, P = .81), subgroup analyses suggest that initiation of EFV, but not other ART, is associated with increased risk of suicidal behavior. When censoring follow-up at ART initiation in the deferred group, the immediate vs deferred HR among those who were prespecified EFV was 3.31 (P = .03) and 1.04 (P = .93) among those with other prespecified ART; (P = .07 for interaction). In the immediate group, the risk was higher among those with prior psychiatric diagnoses, regardless of prespecified treatment group.

Conclusions

Participants who used EFV in the immediate ART group had increased risk of suicidal behavior compared with ART-naive controls. Those with prior psychiatric diagnoses were at higher risk.

Keywords: HIV, suicidal behavior, efavirenz

We compared the incidence of suicidal behavior between human immunodeficiency virus–positive adults with high CD4 count started on antiretroviral therapy immediately or after CD4 count fell below 350 cell/mL. Participants started on efavirenz-based, but not other combinations, had increased risk of suicidal behavior.

Efavirenz (EFV) has been a preferred option for first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) and is recommended in the World Health Organization guidelines for all human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive adults and adolescents [1], preferably as part of a fixed-dose combination [2]. EFV is usually well tolerated, but neuropsychiatric adverse effects can result in treatment switching [3] or serious clinical complications. A metaanalysis of 4 trials in ART-naive patients showed an increased risk of suicidality in those randomized to EFV-based ART compared with those randomized to other regimens [4]. In contrast, several observational studies found no associations of EFV with suicidality [5–7], possibly because, consistent with some prescribing guidelines [8], providers avoided EFV in patients who were at increased risk of suicidality, resulting in a higher proportion of high-risk participants in non-EFV control groups, which might bias observational studies.

The Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial demonstrated clear clinical benefit of immediate ART by decreasing the risk of serious AIDS and serious non-AIDS conditions by 57% in HIV-positive adults with near-normal CD4 cell counts [9]. In START, “suicidal behavior” was the second most frequent type of serious event reported, and 75% of participants randomized to immediate ART initiation used EFV-based ART. We investigated whether initiating EFV increased risk of suicidal behavior more than initiating other ART. This was done by using START’s randomized design to find appropriate control groups.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The START trial has been described previously [9, 10]. In brief, HIV-positive, ART-naive individuals with high CD4 cell counts and no previous AIDS-defining conditions were randomized to initiating ART immediately vs deferring ART until the CD4 cell count dropped below 350 cells/µL or AIDS developed (Supplementary Appendix, Supplementary Figure 1). Each participant’s ART regimen was selected prior to randomization (“prespecified”) by site investigators from a table of recommended initial regimens (Supplementary Materials, section 1). START enrolled participants between 2009 and 2013. This analysis used data accrued through 26 May 2015, the day before the START study results were unblinded and participants in the deferred ART group were recommended starting ART [9].

Outcomes

The START study reported “serious events” that were not related to AIDS irrespective of exposure to ART. These included deaths, unscheduled hospitalizations, and grade 4 adverse events according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Division of AIDS toxicity table [11] (Supplementary Appendix, Supplementary Table 1). All serious events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 19.1, by staff blinded to treatment assignments and ART regimens. The primary endpoint for this analysis are events coded as the MedDRA high-level group term “suicidal and self-injurious behavior,” referred to as “suicidal behavior.”

Baseline Covariates

Age, gender, HIV risk group, prior psychiatric diagnosis (major depression, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder including schizophrenia), and current use of psychotropic drugs (benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotic drugs [neuroleptics], other drugs for bipolar mood disorders, methadone, other prescribed opiates) were obtained by chart abstraction or participant self-report. History of recreational drug use (amphetamines, methamphetamines/ecstasy, cocaine, ketamine, opiates) and heavy alcohol consumption within the past month were estimated from a self-administered questionnaire (Supplementary Appendix, section 2).

Statistical Analyses

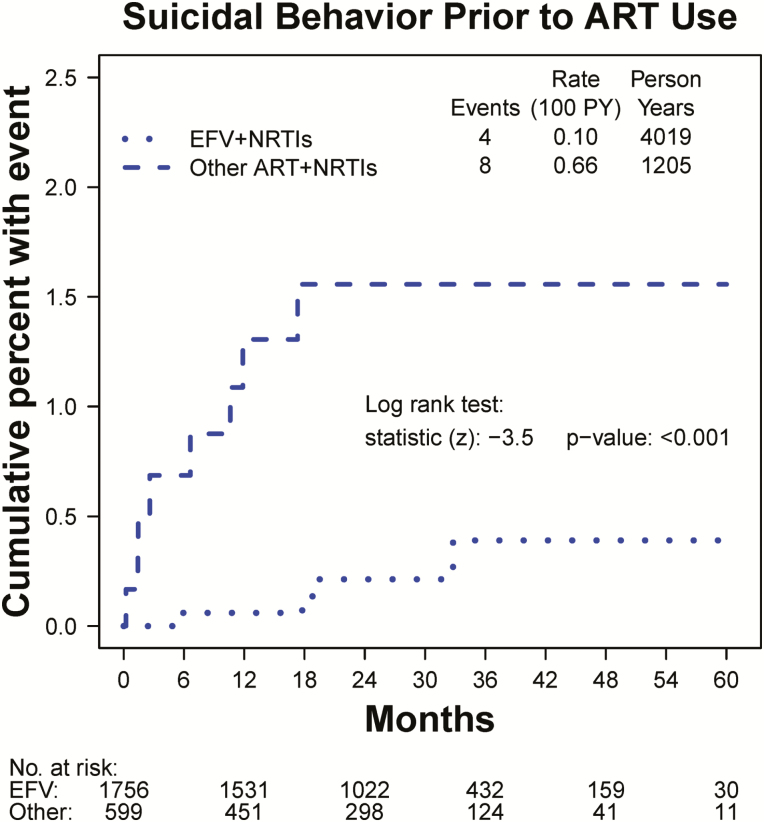

Our primary goal was to determine whether use of EFV-based ART regimens increased the risk of suicidal behavior compared with no ART use or with other ART. To investigate whether participants who were prespecified EFV prior to randomization had the same a priori risk of suicidal behavior as those with other ART, we considered the follow-up in the deferred ART group accrued prior to ART initiation and compared the 2 subgroups for the incidence of suicidal behavior using Kaplan-Meier estimates and a log-rank test (Figure 1). A direct comparison of participants who used EFV vs those who used other ART would be confounded by the differences in a priori risk. To avoid such bias, we used a series of intention-to-treat comparisons between the randomized immediate and deferred ART groups to assess the effect of EFV use (in the immediate ART group) vs an appropriate control group. First, we compared the incidence of suicidal behavior in the immediate vs the deferred ART groups using Cox proportional hazards models overall and separately within the 2 subgroups of participants by prespecified ART type (EFV based and other ART; Figure 2). These treatment comparisons are protected by randomization because the subgroups were defined before randomization. Because most participants in the immediate group started their prespecified regimen (Figure 3), the intention-to-treat comparisons within the 2 subgroups are an approximate comparison of immediate EFV (or other ART) use vs deferring EFV (or other ART). In the second analysis, we restricted follow-up to year 1, since only a few participants in the deferred group initiated ART in the first year (Figure 3). This analysis provides a better approximation of comparing EFV (or other ART) use to no ART while maintaining the protection by randomization. In the third analysis, in order to compare EFV (or other ART) use directly to no ART, we censored follow-up in the deferred group at ART initiation; in the immediate ART group, we started follow-up at ART initiation. Consequently, in the “prespecified EFV” (other ART) subgroup, all participants in the immediate ART group initiated EFV (other ART) at time 0 and were compared to similar participants in the deferred group without ART. In the “prespecified other ART” subgroup, we also censored follow-up at any EFV initiation in the immediate group. For this third analysis, which was not protected by randomization, we provided Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative proportions of participants with suicidal behavior. The 3 analyses were repeated for participants with or without prior psychiatric diagnoses, because the rates of suicidal behavior were higher among those participants.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percent of participants with suicidal or self-injurious behavior in the deferred antiretroviral therapy (ART) group prior to any ART use, within subgroups by pre-specified ART type (efavirenz [EFV] versus other ART). Follow-up is censored at ART initiation. The difference between the curves (P < .001) indicates that participants who were pre-specified EFV-containing regimens had a lower a-priori risk of suicidal behavior compared with those pre-specified other ART. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor PY, person-years.

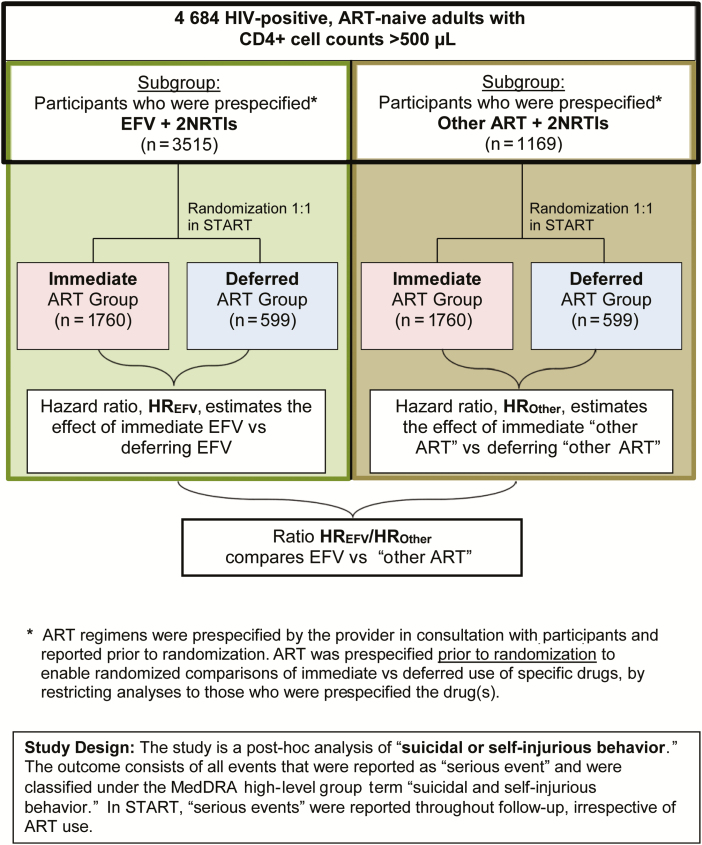

Figure 2.

Study design for investigating associations between efavirenz and suicidal behavior. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HR, hazard ratio; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; START, Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment.

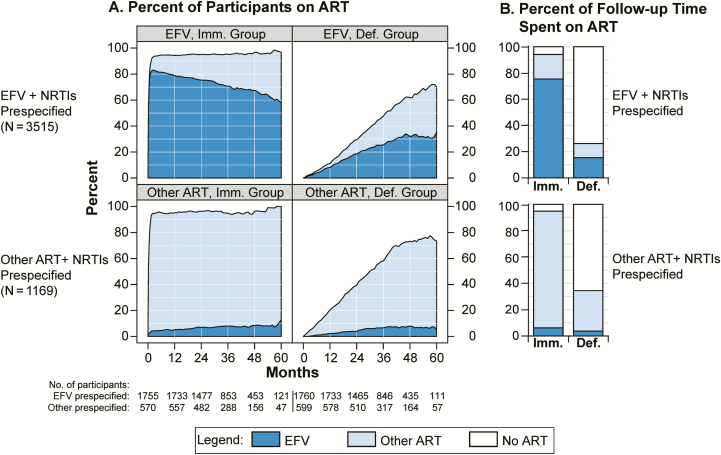

Figure 3.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) and efavirenz (EFV) use in the immediate and deferred ART groups, within subgroups by pre-specified ART type. A, Percent of participants using ART and EFV. B, Percent of follow-up time during which ART and EFV were used. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; Def., deferred; EFV, efavirenz; Imm., immediate; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

In all 3 analyses, we compared the hazard ratios (HRs; immediate vs deferred ART) across the 2 subgroups (prespecified EFV or other ART) by including the interaction between the treatment group and subgroup indicators in expanded Cox proportional hazards models. To estimate the effect of EFV compared with other ART, we calculated the corresponding ratio of HRs (immediate vs deferred ART) for the prespecified EFV subgroup over the prespecified other ART subgroup (Figure 2).

Event rates were estimated without adjustments for baseline characteristics. However, proportional hazards models to compare immediate vs deferred ART were stratified by history of psychiatric diagnoses. We compared baseline characteristics between participants who were prespecified EFV vs other ART using Kruskal-Wallis tests for medians and χ2 tests for proportions. We described ART use through follow-up by plotting the proportion of participants using any EFV, other ART, and no ART in 1-month intervals and by calculating the percentage of total follow-up time during which EFV, other ART, and no ART was used.

To identify predictors for suicidal behavior with EFV use, we restricted the analyses to participants in the immediate ART group who were prespecified and started EFV and estimated associations in Cox proportional hazards models. Initially, we included baseline variables (age, sex, HIV risk group, race/ethnicity, geographic region [high vs low- to middle-income], prior psychiatric diagnoses, psychotropic drug treatment, recreational drug use, heavy alcohol use) and a time-updated indicator variable for EFV use. In the final model, we retained age, sex, HIV risk group, and the time-updated EFV indicator, in addition to those baseline factors that were independently associated with the risk of suicidal behavior, in the initial model. Using predictors with P < .10 in the final model for EFV, we repeated the analyses for participants prespecified other ART. For the strongest predictor (prior psychiatric diagnoses), we tested whether associations with suicidal behavior differed by prespecified ART type in the immediate ART group by testing for an interaction between ART type and predictor.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, versions 9.3 and 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R, version 3 [12]. All tests are 2-sided; P values ≤ .05 denote statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The START study enrolled 4684 participants at 215 sites in 35 countries. Baseline characteristics have been described previously [9, 13]. The prespecified ART regimen included EFV in 3515 (75%) participants. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics by type of prespecified ART. Participants with prespecified EFV less frequently lived in high-income countries (34% vs 81%), were less likely to be current smokers (29% vs 42%), and less likely to have used recreational drugs (24% vs 38%). Within the 2 subgroups, the immediate and deferred treatment groups were well balanced for baseline characteristics (Supplementary Appendix, Supplementary Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Prespecified Antiretroviral Therapy Regimen

| Characteristic | EFV + NRTIs (n = 3515) | Other ARTa + NRTIs (n = 1169) | P Valueb | Total (n = 4684) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years [IQR] | 36 [29, 43] | 36 [29, 45] | .010 | 36 [29, 44] |

| Female, n (%) | 995 (28.3) | 262 (22.4) | <.001 | 1257 (26.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 349 (9.9) | 39 (3.3) | <.001 | 388 (8.3) |

| Black | 1158 (32.9) | 250 (21.4) | <.001 | 1408 (30.1) |

| Latino/Hispanic | 527 (15.0) | 110 (9.4) | <.001 | 637 (13.6) |

| White | 1339 (38.1) | 748 (64.0) | <.001 | 2087 (44.6) |

| Other | 142 (4.0) | 22 (1.9) | <.001 | 164 (3.5) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||

| Africa | 897 (25.5) | 102 (8.7) | <.001 | 999 (21.3) |

| Asia | 326 (9.3) | 30 (2.6) | <.001 | 356 (7.6) |

| Australia | 51 (1.5) | 58 (5.0) | <.001 | 109 (2.3) |

| Europe and Israel | 871 (24.8) | 668 (57.1) | <.001 | 1539 (32.9) |

| South America | 1086 (30.9) | 88 (7.5) | <.001 | 1174 (25.1) |

| United States | 284 (8.1) | 223 (19.1) | <.001 | 507 (10.8) |

| Income region, n (%) | ||||

| High (United States, Europe, Australia) | 1206 (34.3) | 949 (81.2) | <.001 | 2155 (46.0) |

| Low–moderate (Latin America, Africa, Asia) | 2309 (65.7) | 220 (18.8) | <.001 | 2529 (54.0) |

| Likely mode of HIV infection, n (%) | ||||

| Sexual contact with same sex | 1831 (52.1) | 756 (64.7) | <.001 | 2587 (55.2) |

| Sexual contact with opposite sex | 1466 (41.7) | 322 (27.5) | <.001 | 1788 (38.2) |

| Injection drug use | 21 (0.6) | 43 (3.7) | <.001 | 64 (1.4) |

| Blood products, other, unknown | 197 (5.6) | 48 (4.1) | .046 | 245 (5.2) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis, median years [IQR] | 1.0 [0.3, 3.1] | 1.1 [0.4, 3.0] | .068 | 1.0 [0.4, 3.1] |

| CD4,c median cells/µL [IQR] | 651 [583, 768] | 652 [585, 755] | .753 | 651 [584, 765] |

| HIV RNA, median copies/mL [IQR] | 12225 [2879, 41562] | 14304 [3738, 47703] | .022 | 12761 [3025, 43482] |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 1012 (28.8) | 487 (41.7) | <.001 | 1499 (32.0) |

| Prespecified ART regimen, n (%) | ||||

| EFV + NRTIs | 3515 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 | 3515 (75.0) |

| Other non-NRTI not EFV + NRTIs | 0 (0.0) | 171 (14.6) | <.001 | 171 (3.6) |

| PI + NRTIs | 0 (0.0) | 815 (69.7) | <.001 | 815 (17.4) |

| Integrase strand transfer inhibitor + NRTIs | 0 (0.0) | 183 (15.7) | <.001 | 183 (3.9) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis or current psychotropic drug treatment, n (%) | 224 (6.4) | 260 (22.2) | <.001 | 484 (10.3) |

| Prior psychiatric diagnosisd | 109 (3.1) | 162 (13.9) | <.001 | 271 (5.8) |

| Any psychotropic drug use | 183 (5.2) | 196 (16.8) | <.001 | 379 (8.1) |

| Antidepressants | 120 (3.4) | 150 (12.8) | <.001 | 270 (5.8) |

| Benzodiazepines | 62 (1.8) | 50 (4.3) | <.001 | 112 (2.4) |

| Antipsychotic drugs (neuroleptics) | 15 (0.4) | 19 (1.6) | <.001 | 34 (0.7) |

| Other drugs for bipolar mood disorder | 5 (0.1) | 13 (1.1) | <.001 | 18 (0.4) |

| Methadone | 1 (0.0) | 8 (0.7) | <.001 | 9 (0.2) |

| Other opiates | 18 (0.5) | 25 (2.1) | <.001 | 43 (0.9) |

| Ever use of recreational drugs,e n (%) | 858 (24.4) | 442 (37.8) | <.001 | 1300 (27.8) |

| Heavy alcohol use, n (%) | 155 (4.4) | 45 (3.8) | .41 | 200 (4.3) |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

a Ritonavir-boosted PI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor, or non-NRTI other than EFV.

b P values are for comparisons between the EFV + NRTIs and other ART + NRTIs groups. Medians were compared using Kruskal-Wallis tests; percents were compared using χ2 tests.

c Average of 2 screening values.

d Including major depression, bipolar disorder, and psychotic disorder including schizophrenia. These diagnoses were not collected separately.

e Amphetamines and methamphetamines/ecstasy, cocaine, ketamine, and opiates.

Preexisting psychiatric diagnoses were less common in those with prespecified EFV compared with other ART (3.1% vs 13.9%), as was use of psychotropic medication (5.2% vs 16.8%; Table 1). The prevalence of psychiatric conditions at baseline was higher in high-income regions (United States, Europe, and Australia) compared with low- to middle-income regions (Latin America, Africa, and Asia; 11% and 1.4%, respectively).

ART Use Through Follow-up

Figure 3A shows the use of EFV and other ART over time in the immediate and deferred ART groups, separately for participants with prespecified EFV and other ART. Among those prespecified EFV in the immediate ART group, 94% were using ART by month 4 and 82% were on EFV (Figure 3A, upper-left panel). In the deferred arm, median time to ART initiation was 3.2 years, 46% ever initiated ART, and 31% initiated EFV (upper-right panel). Among those with other ART prespecified, ART use in both treatment groups was slightly higher, and a few participants also used EFV (Figure 3A, lower panels).

Figure 3B shows cumulative ART use as a proportion of follow-up time accrued. Among those with EFV prespecified, ART was used for 94% of follow-up time in the immediate group vs 26% in the deferred group, and EFV was used for 76% and 15%, respectively. Among those with other ART prespecified, ART was used for 95% and 35% of time in the immediate and deferred groups, respectively. EFV was used for 6% and 4% of time, respectively.

Suicidal Behavior

Suicidal behavior was reported for 28 participants in the immediate ART group and 25 in the deferred group over a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, rates of 0.39 and 0.34/100 person-years (PY), respectively. The estimated HR (immediate vs deferred group) was 1.07 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.6–1.8); there was no evidence for a treatment difference (P = .81). Among those with EFV prespecified, 19 participants in the immediate ART group reported suicidal behavior vs 12 in the deferred group, rates of 0.35 and 0.22/100 PY, respectively (HR, 1.38; 95% CI, 0.7–2.9; Table 2). Among those with other ART prespecified, 9 (rate 0.50/100 PY) and 13 participants (rate 0.69/100 PY) had suicidal behavior, respectively (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.3–1.7). The ratio between the HRs, comparing the prespecified EFV subgroup vs the other ART subgroup for “excess risk” of suicidal behavior in the immediate group, was not significant (HR, 1.86; P = .24).

Table 2.

Suicidal and Self-Injurious Behavior by Randomization Arm and Prespecified Antiretroviral Therapy Groups

| N | Immediate ART | Deferred ART | HRa | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | HR Ratiob |

P-Value for Interactionc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Participants With Events | Rate per 100 PY | Number of Participants With Events | Rate per 100 PY | |||||||

| ITT analysis, mean follow-up 3 years | ||||||||||

| EFV prespecified | 3515 | 19 | 0.35 | 12 | 0.22 | 1.38 | (0.7, 2.9) | .39 | 1.86 | 0.24 |

| Other ART prespecified | 1169 | 9 | 0.50 | 13 | 0.69 | 0.74 | (0.3, 1.7) | .49 | ||

| ITT analysis, follow-up truncated at 1 year after randomization | ||||||||||

| EFV prespecified | 3515 | 9 | 0.52 | 2 | 0.11 | 3.74 | (0.8, 17.5) | .09 | 3.67 | 0.15 |

| Other ART prespecified | 1169 | 7 | 1.25 | 7 | 1.19 | 1.02 | (0.4, 2.9) | .96 | ||

| Censoring deferred arm participants at ART initiation | ||||||||||

| EFV prespecifiedd | 3394 | 18 | 0.36 | 4 | 0.10 | 3.31 | (1.1, 9.9) | .03 | 3.18 | 0.07 |

| Other ART prespecifiede | 1137 | 9 | 0.56 | 8 | 0.66 | 1.04 | (0.4, 2.7) | .93 | ||

Cox proportional hazards models were used for this analysis.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention to treat; PY, person-years.

aHR (immediate/deferred), estimated in Cox proportional hazards models, stratified by history of psychiatric diagnosis.

bRatio of HRs (immediate/deferred) within the EFV prespecified subgroup over the other ART prespecified subgroup.

cP value for the interaction between indicators for treatment group and prespecified ART regimen; compares HRs (immediate/deferred) between subgroups by prespecified ART.

dOf these events, 6 and 0, in the immediate vs deferred arms, respectively, occurred among 100 participants with prior psychiatric diagnoses. The immediate group excludes participants who did not start ART. Follow-up time starts at EFV start date. Of the 3515 participants with EFV in the prespecified regimen, 117 in the immediate arm were excluded (32 never started ART, 85 never used EFV), and 4 in the deferred arm were excluded (3 started ART at randomization, 1 participant was lost to follow-up at randomization).

eOf these events, 5 and 2, in the immediate vs deferred arms, respectively, occurred among 161 participants with prior psychiatric diagnoses. Of the 1169 participants without EFV in the prespecified regimen, 32 were excluded (in the immediate group, 7 never started ART, and for 25, the first ART regimen contained EFV). The immediate group excludes participants who did not start ART. Follow-up time starts at ART start date and was censored at EFV start.

We repeated the analyses for the first year of follow-up only. Among those with EFV prespecified, the HR was 3.74 (95% CI, 0.8–17.5; P = .09) compared with an HR of 1.02 among those with other ART prespecified (Table 2). However, event numbers were small in this analysis, CIs were large, and there was insufficient evidence for heterogeneity between the subgroups (HR, 3.67; P = .15).

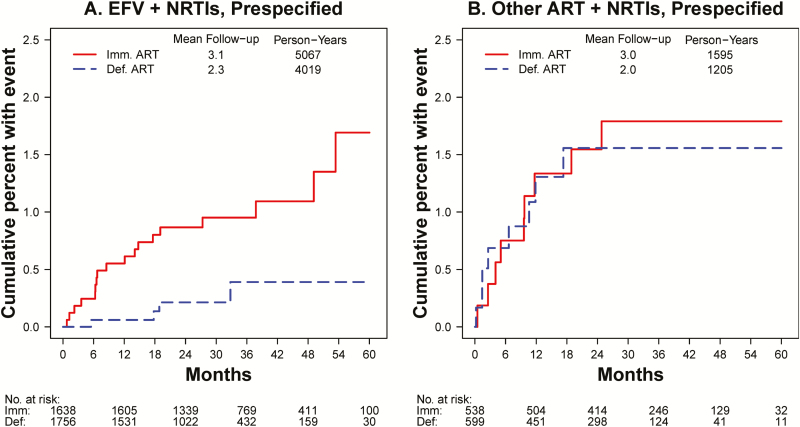

In the third analysis, we compared EFV (or other ART) use to no ART by starting follow-up in the immediate group at ART initiation and censoring follow-up in the deferred group at ART initiation. Among those with EFV prespecified, 18 participants (0.36/100 PY) experienced suicidal behavior in the immediate group (1 event occurred in a participant who was excluded in this analysis because the participant never used EFV) compared with 4 (0.10/100 PY) in the deferred group (HR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.1–9.9; P = .03). Among those with other ART prespecified, rates in both treatment groups were higher (0.56 and 0.66/100 PY), but the HR was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.4–2.7; P = .93). The excess risk of suicidal behavior in the immediate ART group vs no ART was 3.18-fold higher among those with EFV prespecified compared with those in the other ART subgroup, but there was insufficient evidence for heterogeneity between subgroups (P = .07; Table 2). For the last comparison, the Kaplan-Meier estimates for the cumulative proportion of participants with suicidal behavior are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative percent of participants with suicidal or self-injurious behavior, within subgroups by pre-specified antiretroviral therapy (ART) type. In the deferred ART group, follow-up is censored at ART initiation. A, Kaplan-Meier estimates for participants who were pre-specified efavirenz (EFV)-containing ART regimens. In the immediate ART group, follow-up time is started at EFV initiation, excluding 116 (6.6%) participants who never initiated EFV. B, Kaplan-Meier estimates for participants whose pre-specified regimen did not contain EFV. In the immediate group, follow-up time is started at ART initiation, excluding 32 participants who never initiated ART or whose first regimen contained EFV; for the 31 participants who started EFV, follow-up is censored at EFV start. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; Def., deferred; EFV, efavirenz; Imm., immediate; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

Of the 53 suicidal behavior events, 3 were completed suicide, all in the deferred ART group and after ART initiation. Two of these participants had preexisting depression and anxiety/depression and were treated for these conditions. Both were on Truvada plus darunavir/ritonavir. The third participant had a history of alcohol abuse and started EFV-based ART 18 months before the suicide. Table 3 shows the components of suicidal behavior by MedDRA preferred term for each of the comparisons in Table 2.

Table 3.

Number of Participants With Suicidal and Self-Injurious Behavior Included in Each of the 3 Analyses in Table 2 and the Composition of These Events by Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (Version 19.1) Preferred Terms

| Complete Follow-up, ITT Analysis | First Year, ITT Analysis | Deferred Arm Censored at ART Initiationa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Deferred | Immediate | Deferred | Immediate | Deferred | ||

| Suicidal behavior events | |||||||

| All participants | 28 | 25 | 16 | 9 | 27 | 12 | |

| EFV + NRTIs prespecified | 19 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 18 | 4 | |

| Other ART + NRTIs prespecified | 9 | 13 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 8 | |

| Breakdown of suicidal behavior by MedDRA preferred term | |||||||

| All participants | Completed suicide | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intentional self-injury | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Self-injurious ideation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 10 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 10 | 3 | |

| Suicide attempt | 18 | 14 | 12 | 7 | 17 | 8 | |

| EFV + NRTIs prespecified | Completed suicide | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intentional self-injury | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

| Suicide attempt | 13 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 2 | |

| Other + NRTIs prespecified | Completed suicide | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Self-injurious ideation | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Suicidal ideation | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Suicide attempt | 5 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; EFV, efavirenz; ITT, intention to treat; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 19.1); NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

a In this analysis, follow-up in the immediate ART group was started at EFV (ART) initiation, which excluded participants who did not start EFV (ART) or had experienced suicidal behavior before initiating EFV (ART).

The incidence of suicidal behavior was substantially higher among the 371 participants with prior psychiatric diagnosis; among those prespecified other ART, 8 of 162 participants with prior psychiatric diagnoses experienced an event (1.7/100 PY) compared with 14 of 1007 without diagnoses (0.5/100 PY; P = .003). Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 show the event rates and HRs from Table 2 for participants with and without prior psychiatric diagnoses, respectively. Among the 109 participants with prior psychiatric diagnoses who were prespecified EFV, none experienced suicidal behavior in the deferred ART group compared with 6 (2.7 per 100 PY) in the immediate group after starting EFV (Supplementary Table 3).

Predictors of Suicidal Behavior

A prior psychiatric diagnosis was the strongest predictor of suicidal behavior among participants in the immediate group who started ART, both among those who were prespecified EFV (HR, 12.5; 95% CI, 4.7–33.6; P < .001; Table 4) and those prespecified other ART (HR, 9.3; 95% CI, 2.4–36.4; P = .001; Supplementary Table 5); there was no evidence for a difference by ART type (P = .79 for interaction). Among those who were prespecified EFV, heavy alcohol use and recreational drug use were independently associated with increased risk (HR of 4.6 and 2.6, respectively), while the risk decreased with age (HR, 0.51 per 10 years older). The time-updated indicator for EFV use was not associated with risk of suicidal behavior (HR, 1.4; P = .74); however, power for this variable was low because almost all participants started EFV shortly after randomization (Table 4). Median time from EFV start to suicidal behavior was 10.2 months.

Table 4.

Factors Associated With Suicidal and Self-Injurious Behavior Among Participants in the Immediate Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Group Who Were Prespecified Efavirenz + Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors and Who Started ART

| Factors | Multivariate Analysisa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | |

| Age (per 10 years older) | 0.51 | (0.29, 0.89) | .018 |

| Gender and risk group | |||

| Female vs male | 0.68 | (0.19, 2.47) | .55 |

| Men who have sex with men vs other male | 0.49 | (0.15, 1.59) | .23 |

| Prior psychiatric diagnosisb | 12.49 | (4.65, 33.59) | <.001 |

| Recreational drug use, ever | 2.58 | (0.96, 6.95) | .06 |

| Heavy alcohol use | 4.62 | (1.46, 14.61) | .009 |

| Efavirenz started (time-updated)c | 1.42 | (0.18, 11.08) | .74 |

| Number of participants | 1723 | ||

| Number of suicidal behavior events | 19 | ||

Number in group (number of events) for categorical variables: female = 484 (3); men who have sex with men = 909 (12); other male = 330 (4); prior psychiatric diagnosis = 70 (9); ever use of recreational drugs = 409 (11); heavy alcohol use = 76 (4).

aHazard ratios from 1 multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model with all listed variables.

bDiagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, or psychotic disorder including schizophrenia.

cIndicator variable, switches from 0 to 1 at the date of efavirenz start (if ever).

DISCUSSION

In the START study, there was no overall difference between the immediate vs deferred ART groups in the incidence of suicidal behavior events. However, among participants whose prespecified ART regimen included EFV, those in the immediate arm who started EFV had a higher risk of suicidal behavior (HR, 3.31; 95% CI, 1.19.9; P = .03) compared with those who were randomized to the deferred arm and were not yet using any ART. Conversely, among participants who were prespecified other ART, there was no excess risk of suicidal behavior in the immediate ART group (HR, 1.04). This is consistent with a post hoc metaanalysis that combined data from 4 ART-naive trials [4]. In contrast, cohort analyses and data extracted from regulatory agency databases have failed to observe any excess risk of suicidality associated with EFV [5–7]. Observational studies that compared EFV use to other ART are unreliable. However, because EFV is often avoided for patients with elevated risk of suicidal behavior, resulting in higher a priori risk of suicidal behavior in the other ART group. This higher a priori risk was evident in the START study (Figure 1). We minimized bias by using the randomized design of the study to identify control groups for EFV (or other ART) prior to randomization.

In the general population, patients with severe depression and other serious psychiatric conditions are at higher risk for suicidality [14–16]. In our study, the strongest predictor of suicidal behavior in the immediate ART group was a preexisting psychiatric diagnosis, both among those using EFV and those with other ART. Given the higher absolute risk of suicidal behavior among those with psychiatric conditions, the association between EFV exposure and suicidal behavior supports the recommendation in national and regional guidelines to avoid prescribing EFV for patients with past or current psychiatric conditions [8, 17, 18]. Recreational drug use, including alcohol, was also independently associated with suicidal behavior, which is also consistent with findings in the general population and those with other chronic conditions, particularly at a younger age [15, 19, 20].

In a recent systematic review and metaanalysis, a higher incidence of severe neuropsychiatric adverse events but not suicidality was observed in ART-naive adults randomized to EFV-based ART compared with other regimens. However, there were no completed suicides in the metaanalysis studies and the overall rate of suicidal ideation was extremely low (0.6%), affecting their power to investigate differences between groups [21].

Screening for psychiatric conditions (mainly depression) before prescribing EFV could reduce the risk of suicidality. However, screening may not be feasible or affordable, particularly in low- to middle-income countries where EFV continues to be frequently used in first-line ART. The Encore1 trial reported a lower rate of EFV-related adverse events in patients treated with reduced compared with standard doses [22], suggesting that lower doses of EFV may provide a better safety profile.

The main strengths of our study are the use of START’s randomized design and the standardized reporting of serious suicidal behavior events. Our study had several limitations. First, it was a post hoc analysis of a trial in which EFV exposure was not the randomized intervention. However, by comparing the immediate and deferred treatment groups within subgroups by prespecified ART type, we estimated the effect of EFV (and other ART) vs randomized control groups, thus minimizing selection bias. Second, not all participants in the immediate group started their prespecified regimen, and some discontinued prespecified EFV. However, adherence overall was high (Figure 3). Third, participants in the deferred group gradually started ART; while we censored follow-up at ART start in the third analysis, this censoring compromises the protection by randomization. Fourth, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors differed between the EFV and other ART groups. Finally, the number of events was low, which limited the power; therefore, results need to be interpreted with caution.

In conclusion, in the START study, ART-naive participants who used EFV in the immediate ART group had an increased risk of suicidal behavior compared with ART-naive controls. Preexisting psychiatric conditions were the strongest predictor of suicidal behavior. Therefore, screening for major psychiatric conditions before EFV initiation would be advisable.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. Conception and design: A. A. P., N. C., E. M., D. A. C., B. G., S. S. Analysis and interpretation of the data: B. G., S. S. Drafting of the article: A. A. P., B. G., S. S. Provision of study materials or patients: P. M. F., W. M. C., C. K., J. F., V. O., C. A., D. S., J. S. M, E. K. Collection and assembly of data: P. M. F., W. M. C., C. K., J. F., V. O., C. A., D. S., J. S. M., E. K. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: S. C., N. C., P. B., K. L. K., E. M., D. A. C. Final approval of the article: all coauthors.

Acknowledgments. We gratefully acknowledge the commitment of the participants and investigators in the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) study, without whom this analysis would not have been possible. Investigators in the START study group have been listed previously [9].

Disclaimer. The funder had a role in study design and interpretation of data and the writing of the report through the membership of K. L. K. and P. B. on the writing committee. The funder had no role in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Financial support. The START study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UM1-AI068641 and UM1-AI120197); National Institutes of Health Clinical Center; National Cancer Institute; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; National Institute of Mental Health; National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases; Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le SIDA et les Hépatites Virales (France); National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia); National Research Foundation (Denmark); Bundes ministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Germany); European AIDS Treatment Network; Medical Research Council (United Kingdom); National Institute for Health Research; National Health Service (United Kingdom); and University of Minnesota. Antiretroviral drugs were donated to the central drug repository by AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmith-Kline/ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. A. P. has received grants from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Cilag, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. A. A. P., B. G., and S. S. (or the institutions where they work) have received grants from NIH during the conduct of the study. E. M. has received grants from Merck and Janssen outside the submitted work. P. M. F. has received personal fees from Merck outside the submitted work. C. K. has received consultancy fees from MSD, Janssen, and ViiV, research grant from ViiV and Janssen, and travel grants from MSD, Gilead, and Janssen outside the submitted work. J. S. M. has received grants from Fundación Fundación para la Investigación a Beneficio de Inmunocomprometidos/Latin America Coordination of Academic Research during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer, Stendahl, Gilead, Abbvie, BMS, and GSK outside the submitted work. C. A. received a grant from the University of Minnesota during the conduct of the study. P. B. is an employee of the US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Mental Health. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. June 2016 ed. Layout L’IV Com Sàrl, Villars-sous-Yens, Switzerland: WHO Press, 2016:480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nelson LJ, Beusenberg M, Habiyambere V, et al. Adoption of national recommendations related to use of antiretroviral therapy before and shortly following the launch of the 2013 WHO consolidated guidelines. AIDS 2014; 28(Suppl 2):S217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scourfield A, Zheng J, Chinthapalli S, et al. Discontinuation of Atripla as first-line therapy in HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS 2012; 26:1399–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mollan KR, Smurzynski M, Eron JJ, et al. Association between efavirenz as initial therapy for HIV-1 infection and increased risk for suicidal ideation or attempted or completed suicide: an analysis of trial data. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nkhoma ET, Coumbis J, Farr AM, et al. No evidence of an association between efavirenz exposure and suicidality among HIV patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in a retrospective cohort study of real world data. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95:e2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Napoli AA, Wood JJ, Coumbis JJ, Soitkar AM, Seekins DW, Tilson HH. No evident association between efavirenz use and suicidality was identified from a disproportionality analysis using the FAERS database. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith C, Ryom L, Monforte Ad, et al. Lack of association between use of efavirenz and death from suicide: evidence from the D:A:D study. J Int AIDS Soc 2014; 17:19512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Waters L AN, Angus B, Boffito M, et al. BHIVA guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015 (2016 interim update). In: (BHIVA) BHA, ed. London, UK: BHIVA; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lundgren JD, Babiker AG, Gordin F, et al. ; Group ISS Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:795–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lundgren J, Babiker A, Gordin F, et al. ; Group ISToATS Why START? Reflections that led to the conduct of this large long-term strategic HIV trial. HIV Med 2015; 16(Suppl 1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Department of Health and Human Services NIoH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Division of AIDS. Division of AIDS table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events, version 1.0. In: National Institutes of Health NIoAaID, Division of AIDS, ed. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carey D, Puls R, Amin J, et al. ; ENCORE1 Study Group Efficacy and safety of efavirenz 400 mg daily versus 600 mg daily: 96-week data from the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority ENCORE1 study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sharma S, Babiker AG, Emery S, et al. ; International Network for Strategic Initiatives in Global HIV Trials START Study Group Demographic and HIV-specific characteristics of participants enrolled in the INSIGHT Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) trial. HIV Med 2015; 16(Suppl 1):30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katon WJ. Epidemiology and treatment of depression in patients with chronic medical illness. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2011; 13:7–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singhal A, Ross J, Seminog O, Hawton K, Goldacre MJ. Risk of self-harm and suicide in people with specific psychiatric and physical disorders: comparisons between disorders using English national record linkage. J R Soc Med 2014; 107:194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cho SE, Na KS, Cho SJ, Im JS, Kang SG. Geographical and temporal variations in the prevalence of mental disorders in suicide: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2016; 190:704–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Africa DoHRoS. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV and the Management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults. In: Health Do, ed. Pretoria, 0001, South Africa: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2015:136. [Google Scholar]

- 18. EACS. EACS Guidelines. In: (EACS) EACS, ed. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS); 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19. McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguin M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychol Med 2008; 38:407–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dumais A, Lesage AD, Alda M, et al. Risk factors for suicide completion in major depression: a case-control study of impulsive and aggressive behaviors in men. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:2116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ford N, Shubber Z, Pozniak A, et al. Comparative safety and neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with efavirenz use in first-line antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69:422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Group ES, Puls R, Amin J, et al. Efficacy of 400 mg efavirenz versus standard 600 mg dose in HIV-infected, antiretroviral-naive adults (ENCORE1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 383:1474–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.