Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral drugs have been associated with changes in lipids, fat mass and dat distribution. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) has been shown to have a more favorable metabolic profile than other drugs in its class. However, the metabolic effects of TDF in preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are unknown.

Methods

We evaluated the effects of TDF/emtricitabine (FTC) on lipids and body composition in a blinded, placebo-controlled PrEP trial. Participants enrolled in a metabolic subcohort (N = 251, TDF/FTC; N = 247, placebo) consented to fasting lipid panels, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans for body composition, and pharmacologic testing of drug metabolites at baseline and every 24 weeks thereafter.

Results

Lean body mass was stable and unaffected by TDF/FTC. Body weight increased in both groups but was lower on TDF/FTC through week 72. This difference was explained by lower fat accumulation on TDF/FTC. The net median percent difference (standard error, P value) for TDF/FTC vs placebo at week 24 was −0.8% (0.4%, P = .02), +0.3% (0.4%, P = .46), and −3.8% (1.4%, P = .009) for total, lean, and fat mass, respectively. There was no apparent differential regional fat accumulation on TDF/FTC. Decreases in cholesterol, but not triglycerides, were seen in TDF/FTC participants, with detectable drug levels compared to placebo.

Conclusions

TDF/FTC for PrEP showed cholesterol reductions and appeared to transiently suppress the accumulation of weight and body fat compared to placebo. There was no evidence of altered fat distribution or lipodystrophy during daily oral TDF/FTC PrEP.

Clinical Trials Registration

Keywords: lipids, lipodystrophy, tenofovir/emtricitabine, PrEP, body composition

Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) leads to small losses of body fat but does not appear to affect fat distribution or lean body mass. It does modestly lower lipid levels as observed in HIV treatment.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention has been revolutionized by the use of antiretroviral drugs (ARVDs) for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Multiple clinical trials have shown that oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) with and without emtricitabine (FTC) used as PrEP prevents HIV infection when taken as prescribed, has an excellent safety profile [1–6], and is broadly acceptable for diverse populations at risk of HIV infection [7–12].

In people with HIV infection, some ARVDs have been associated with metabolic changes, including peripheral lipoatrophy, central adiposity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia [13, 14]. This is particularly apparent with thymidine analogues and some protease inhibitors. TDF appears to have a more favorable metabolic profile, and use of TDF compared to stavudine or zidovudine has shown decreases in lipids and increases in limb fat [15–20]. However, it has been difficult to evaluate the specific effects of TDF or TDF/FTC on metabolic parameters in isolation, given a constellation of other factors that may influence lipids and body composition, including HIV infection, the host response to HIV, and other drugs in the ARVD regimen. PrEP trials provide an opportunity to study the effects of TDF/FTC on body composition and fat distribution in the absence of HIV infection and other confounders.

Further, rigorous documentation of safety is imperative in those taking a medication for prophylaxis, and perceptions of ARVD toxicity are an important barrier to PrEP uptake [7, 21]. Here, we provide the first report of metabolic effects of TDF/FTC PrEP on fasting lipids, body composition, and fat distribution in a cohort nested within a randomized, placebo- controlled trial of TDF/FTC as PrEP.

METHODS

Study Design

The iPrEx trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trial of daily, oral TDF/FTC vs placebo for the prevention of HIV acquisition. Between July 2007 and December 2009, the trial enrolled 2174 cisgender men and 325 transgender women who have sex with men (MSM/TGW) in 6 countries. The study design and primary results have been described elsewhere [1]. All participants were followed monthly for HIV acquisition, and laboratory safety analyses were performed monthly for the first 16 weeks, week 24, and then every 12 weeks. Physical exams were performed every 6 months.

Metabolic Substudy

An opt-in metabolic substudy, which included whole-body dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning, was offered to all eligible iPrEx participants enrolled in Chiang Mai, Thailand; San Francisco, California; and Cape Town, South Africa and to participants in Lima, Peru, and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, who enrolled in iPrEx after DXA scanning became available at those clinics [22]. The only additional eligibility criteria for the DXA substudy were weight <120 kg and no use of oral or inhaled glucocorticoids at entry. Substudy visits included venipuncture for an 8-hour fasting blood sample and spine, hip, and whole-body DXA scan. Visits were completed at baseline (prior to the first dose of study drug), at 24-week intervals during randomized treatment, at treatment discontinuation, and 24 weeks after stopping the study drug. Substudy participants gave written informed consent for the additional testing and visits. DXA scanning began in July 2008 and was completed in February 2011.

Participants in San Francisco and Rio de Janeiro were scanned on Lunar Prodigy (Madison, Wisconsin) DXA instruments; those in Cape Town and Chiang Mai were scanned on Hologic Discovery (Waltham, Massachusetts) devices; and those in Lima were scanned on a Hologic Explorer (Waltham, Maxsachusetts). All clinics followed manufacturer-recommended calibration and maintenance procedures. A single study-specific spine phantom was circulated for scanning at all clinics for quality control. Each clinic’s calibration and maintenance records were reviewed to ensure consistency throughout the study. Scans were analyzed locally following a standardized protocol and reviewed centrally. With very few exceptions, all scans were analyzed by the same person at each DXA facility.

Lipid Testing

Fasting serum specimens from substudy visits were frozen and saved for centralized batch analysis (Quest Laboratories) for testing levels of triglycerides and total, high-density, and calculated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, LDL-C).

Plasma and Intracellular Tenofovir and Emtricitabine Measurements

In previous reports, we found a substantial portion of the participants were using TDF/FTC less than daily, and half had no detectable PrEP drug in the active arm, indicating that less than 1 tablet was being taken per week [23]. To fully understand the biological effects of the drugs, all DXA substudy participants assigned to TDF/FTC had tenofovir (TFV) and FTC concentrations at weeks 24, 48, and 72 measured in stored plasma. Intracellular TFV diphosphate (TFV-DP) concentrations at week 24 were measured in viably cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells [22, 23]. These measurements permitted analysis by randomized assignment as well as time-varying drug exposure.

Data Analyses

Target enrollment in the DXA substudy was 500. Baseline characteristics were compared by an unequal-variance t test for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The Fisher exact test was also used to compare categorical variables during follow-up. Percentage and absolute changes in parameters were calculated relative to baseline. We emphasized median changes, as have similar studies [17–20], to limit the influence of extreme values. Median differences in parameters by groups were compared by quantile regression [24] with a robust standard error to account for serial scans [25]. Median regression was also used to relate TFV-DP at week 24 to week 24 lipids and body composition. Results in seroconverters were censored beginning at the first visit with laboratory evidence of HIV infection. Outcomes were compared by randomized assignment as well as by drug detection result (detected vs below the level of quantitation [BLQ]) based on the pharmacology specimen collected at the visit at which the outcome was measured. All P values are 2-sided. Analyses were performed using STATA, version 14.2 [26].

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 498 HIV-uninfected persons (247 TDF/FTC, 251 placebo) were enrolled in the metabolic study; 419 (n = 214, 87%: TDF/FTC; n = 216, 86%: placebo) had at least 1 follow-up DXA scan, and 214 (87%) and 214 (85%) had at least 1 follow-up lipid value on TDF/FTC and placebo, respectively. The median number of lipid values was 4 in both groups. Of the 1638 lipid values during the study medication period, 1634 (>99%) were reported by participants as fasting lipid values.

Baseline demographics did not differ by randomized treatment (Table 1). Participants had a median (interquartile range) age of 25 (21–33) and 24 (21–32) years on TDF/FTC and placebo, respectively (P = .59). Most participants had baseline body mass index (BMI) in the normal range (≥18.5 to <25 kg/m2, 56% TDF/FTC, 65% placebo, P = .09). Total cholesterol was <200 mg/dL in 86%.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics of the 498 Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Negative Participants in the Metabolic Cohort

| Demographics | Placebo (N = 247) | Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine (N = 251) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry (years)a | 24 (21–32) | 25 (21–33) | .59 |

| Race (self-reported)b | |||

| Black/African American | 25 (10%) | 37 (15%) | .30 |

| White | 43 (17%) | 45 (18%) | … |

| Mixed/Otherc | 133 (53%) | 115 (47%) | … |

| Asian | 50 (20%) | 50 (20%) | … |

| Country of enrollment | .94 | ||

| Peru | 106 (43%) | 114 (45%) | |

| Brazil | 29 (12%) | 25 (10%) | |

| South Africa | 31 (13%) | 28 (11%) | |

| Thailand | 47 (19%) | 47 (19%) | |

| United States | 34 (14%) | 37 (15%) | |

| Trans identityb | 26 (10%) | 26 (11%) | 1.00 |

| Time on study drug (weeks)a | 61 (40–87) | 64 (43–88) | .94 |

| Height (cm)a | 170 (165–177) | 169 (165–176) | .41 |

| Weight (kg)a | 66.1 (59.5–76.0) | 66.4 (58.6–76.5) | .46 |

| Lean mass (kg)a | 50.6 (46.2–55.8) | 50.6 (45.8–55,2) | .46 |

| Fat mass (kg)a | 12.4 (9.1–17.5) | 12.4 (8.3–18.3) | .44 |

| Percent body fat (%) | 19 (15–24) | 19 (14–24) | .46 |

| BMI (kg/m2)a | 23 (21–26) | 23 (20–25) | .65 |

| BMI categoryb | |||

| <18.5 | 20 (8%) | 29 (12%) | .09 |

| 18.5 to <25 | 163 (65%) | 138 (56%) | … |

| 25 to 30 | 54 (22%) | 70 (28%) | … |

| ≥30 | 14 (6%) | 10 (4%) | … |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL)a | 162 (137–186) | 160 (137–182) | .75 |

| Total cholesterol (≥ 200 mg/dL)b | 31 (13%) | 35 (15%) | .69 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)a | 44 (37–54) | 44 (39–52) | .96 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL)a | 93 (74–114) | 92 (75–112) | .72 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)a | 87 (62–122) | 85 (66–126) | .29 |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

aSummary is median (interquartile range) with P value by unequal variance t test.

bSummary is n (%) with P by the Fisher exact test.

cParticipants in Peru and Brazil frequently identified as being of mixed race.

Observational duration and drug exposure were comparable between the arms. Median time on study was 64 and 61 weeks on TDF/FTC and placebo, respectively, with an average of 3.2 DXA scans per participant in the metabolic substudy. Drug level testing data in TDF/FTC participants were complete in 425 of the 484 (88%) post-baseline scans through week 72. The metabolic cohort had been previously characterized and reported on in our analyses of bone mineral density [23].

Body Weight

Weight

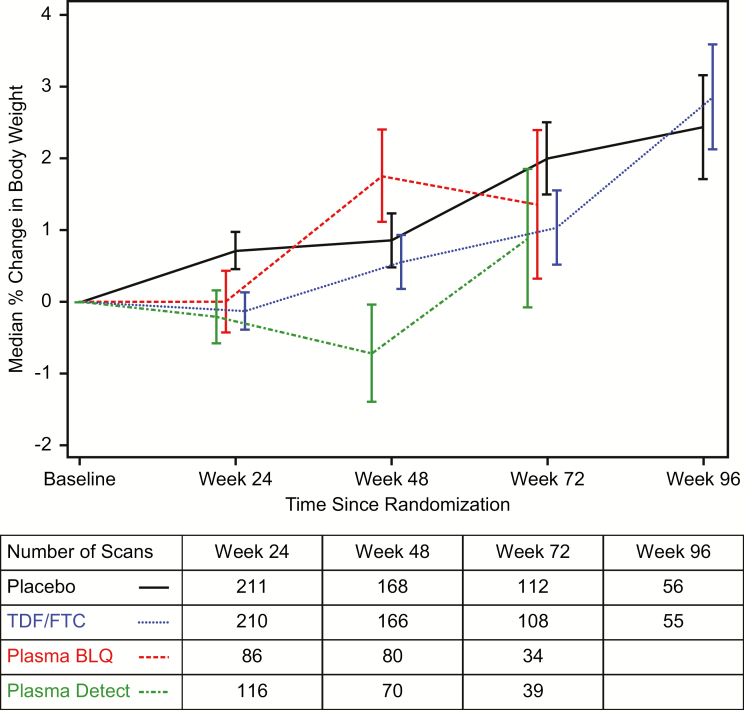

Weight increased in the placebo group, with median percent change from baseline (standard error [SE]) of +2.4% (0.7%) at 96 weeks (Figure 1). Weight decreased on TDF/FTC at week 24 by −0.1% (0.3%), with increases at later visits. The median net weight change on TDF/FTC compared to placebo was −0.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], −1.5% to −0.1%, P = .02) at week 24; by week 96, weights were similar, net difference +0.4% (95% CI, −1.6% to 2.4%, P = .69). Net median differences compared to placebo ranged from −0.9% to −1.6% through week 72 at visits with plasma drug detected.

Figure 1.

Median percentage increase in body weight in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with at least 1 dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scan available in each visit window. Multiple scans by individuals in windows were averaged. x-axis (panels A and B): weeks since randomization. y-axis (panels A and B): median percent change in body weight from baseline. Abbreviations: BLQ, below level of quantitation; FTC, emtricitabine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Nausea was reported more frequently in the TDF/FTC group compared to placebo in the overall trial cohort as reported previously [1]. To determine if the nausea was driving weight differences, we calculated the TDF/FTC weight difference at week 24 among participants stratified by reports of nausea through week 24. Median changes (SE) in weight at week 24 were −0.7% (0.5%) among those who reported nausea through week 24 and −1.2% (0.2%) among those who did not (P for interaction = .37).

Data on the proportion of participants who reached weight loss thresholds were similar by group. This result is presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Body Composition

Lean Body Mass

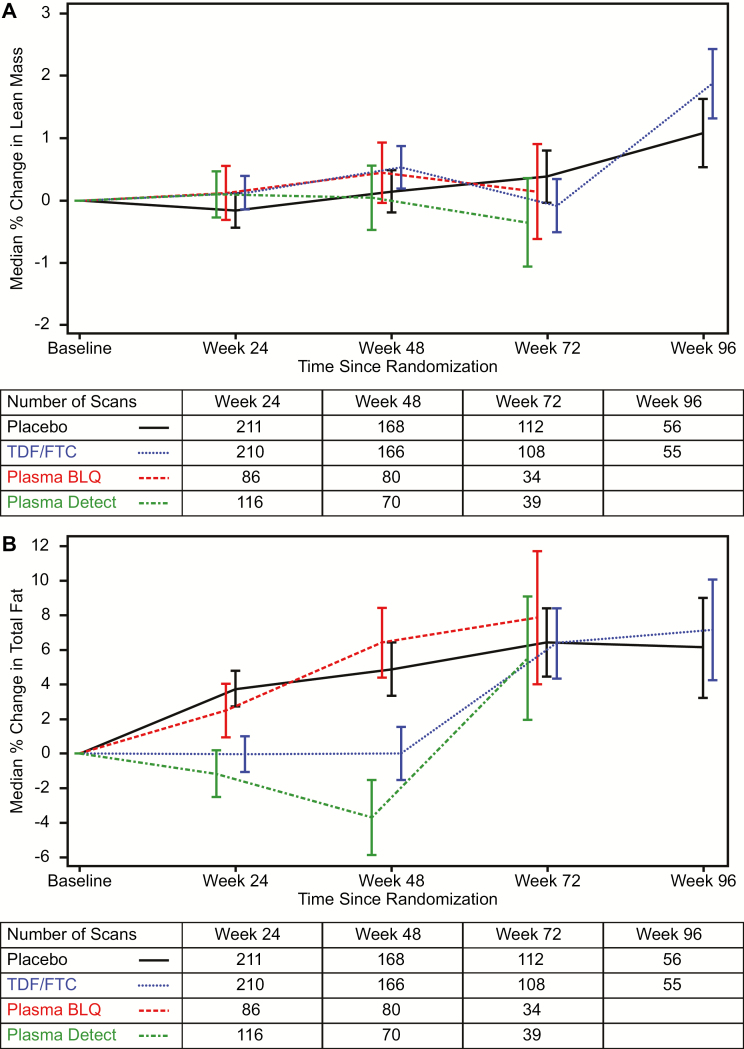

Lean body mass (LBM) was stable in both groups through the follow-up period (Figure 2A). Median changes (SE) at week 48 were +0.5% (0.3%) on TDF/FTC vs +0.1% (0.3%) on placebo (P = .42) compared to baseline LBM — a net median difference of +189 g, (0.95% CI, −303 g to +681 g). Among those with plasma drug detected at week 48, the median (SE) change was +0.0% (0.5%) compared to +0.4% (0.5%) without detection (P = .58). Changes between groups defined by randomization or drug detection were not significant at any time point.

Figure 2.

A, Median percentage increase in lean body mass as measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with at least 1 DXA scan available in each visit window. Multiple scans by individuals in windows were averaged. B, Median percentage increase in total fat mass as measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with at least 1 DXA scan available in each visit window. Multiple scans by individuals in windows were averaged. x-axis (panels A and B): weeks since randomization. y-axis (panel A): median percent change in lean body mass from baseline. y-axis (panel B): median percent change in fat mass from baseline Abbreviations: BLQ, below level of quantitation; FTC, emtricitabine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Overall Fat Mass

The increases in body weight were accounted for by increases in fat mass (Figure 2B). Participants on placebo steadily gained total body fat during the follow-up period, with median percent increase from baseline (SE) of 6.4% (2.0%) at week 72. Participants randomized to TDF/FTC showed no median change overall at weeks 24 and 48, with increases at weeks 72 and 96. Median net differences between randomized groups were −3.8% (95% CI, −6.6% to −0.9%, P = .009) at week 24 and narrowing to +1.0% (95% CI, −7.0% to +9.1%, P = .80) at week 96.

The pattern of differential fat changes was sharper when drug detection by plasma was taken into account, with a net median decrease in those on TDF/FTC with drug detected vs placebo of −4.9% (−644 g) at week 24 (P = .003, compared to placebo) and rebounding to −0.9% (−368 g) at week 72 (P = .83 drug detected at week 72 vs placebo).

At week 48, there was also less fat gain on TDF/FTC (P = .025) compared to placebo and fat loss among those with plasma drug detected at the visit (P < .001 compared to placebo and TDF/FTC without detection). In a multivariate model, week 48 fat changes were not associated with enrolling clinic (P = .54), age (P = .59), race (P = .62), trans identity (P = .17), baseline BMI (P = .57), or baseline fat mass (P = .76). Fat loss was also no greater among those who reported diarrhea (P = .33) or nausea (P = .70) within the first 12 weeks after randomization compared to those who did not. The only significant predictor was detection of TFV in plasma at week 48 (P = .004).

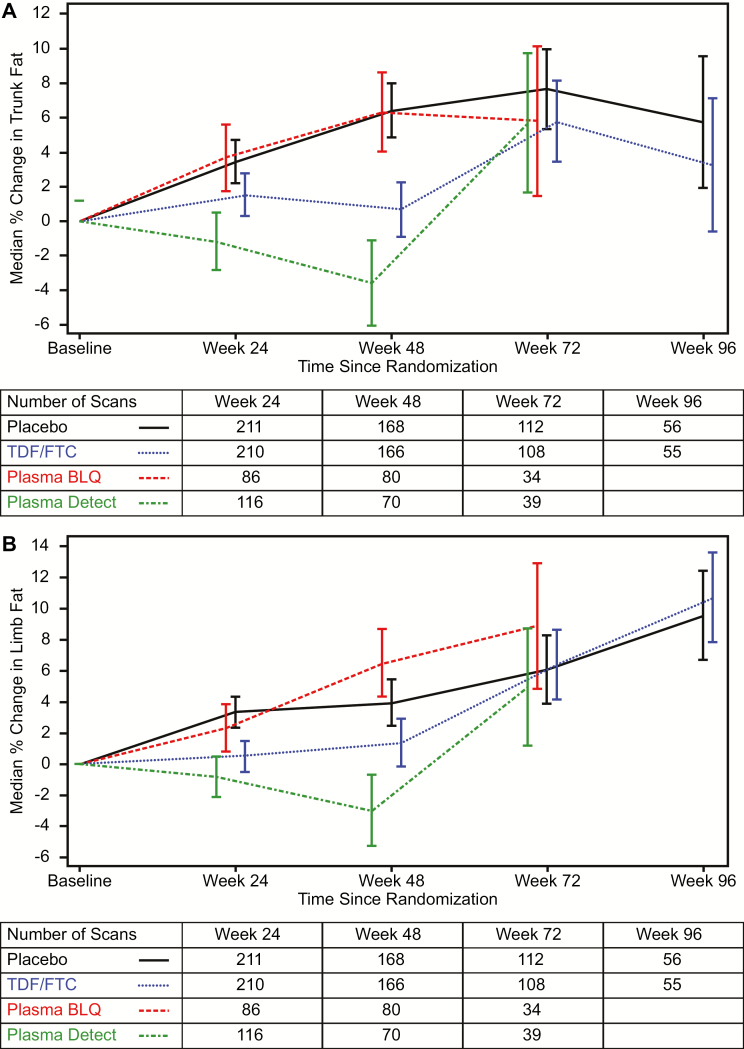

Regional Fat Mass

Trunk fat tended to accumulated more slowly among people in the active arm overall due to a decline in trunk fat among those with drug detected at visits through week 48 (Figure 3A). Trunk fat between randomized groups was statistically significantly lower only at week 48. The median (SE) change in trunk fat at week 48 was +6.4% (1.6%) on placebo, +6.3% (2.3%) in the TDF/FTC group who had no plasma TDF/FTC detected, and −3.6% (2.5%) on TDF/FTC with drug detected at week 48 (P = .98 for no drug detected and P = .001 for detected drug vs placebo, respectively). The change in limb (arm + leg) fat (Figure 3B) at week 48 was a median (SE) of +3.9% (1.5%) on placebo with −3.0% (2.3%) and +6.5% (2.2%) on TDF/FTC with and without plasma drug detected (P = .33 for no drug detected vs placebo and P = .01 for detected drug vs placebo).

Figure 3.

A, Median percentage increase in fat mass in the trunk as measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with at least 1 DXA scan available in each visit window. Multiple scans by individuals in windows were averaged. B, Median percentage increase in fat mass in the limbs (arms and legs) as measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with at least 1 DXA scan available in each visit window. Multiple scans by individuals in windows were averaged. x-axis (panels A and B): weeks since randomization. y-axis (panel A): median percent change in trunk fat mass from baseline. y-axis (panel B): median percent change in limb fat mass from baseline Abbreviations: BLQ, below the level of quantitation; FTC, emtricitabine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

There was no evidence of differential TDF/FTC effect on changes in body fat by region (trunk vs limbs, P for interaction, 0.69, 0.29, 0.62, and 0.53 at weeks 24, 48, 72, and 96). There was also no evidence of interaction by drug detection at any visit.

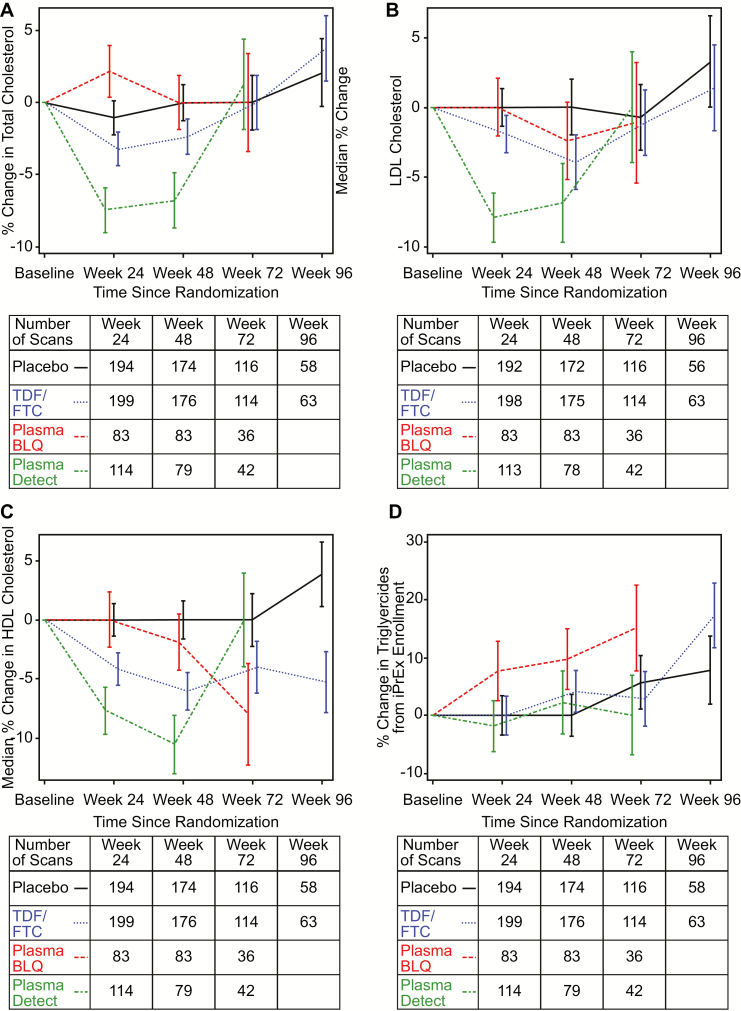

Lipids

Median values of LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol tended to decrease on TDF/FTC from baseline. These changes were nonsignificant for total cholesterol (Figure 4A) and LDL-C (Figure 4B) between randomized groups overall but were significant for HDL-C (Figure 4C). Median (SE, P value) changes from baseline for HDL-C were −6.1% (1.6%, P = .003) on the relative scale and −3.9 mg/dL (1.2, P = .006) on the absolute scale at week 48 on the TDF/FTC arm.

Figure 4.

A, Median percentage increase in fasting total cholesterol in the metabolic cohort+. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with \ lipid results available in each visit window. Multiple results by individuals in windows were averaged. B, Median percentage increase in fasting low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in the metabolic cohort+. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with lipid results available in each visit window. Multiple results by individuals in windows were averaged. C, Median percentage increase in fasting high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with lipid results available in each visit window. Multiple results by individuals in windows were averaged. D, Median percentage increase in triglycerides in the metabolic cohort. Curves are stratified by randomized treatment (placebo vs tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC]) with the TDF/FTC group further stratified by detection of either tenofovir or FTC in a plasma sample (“Detected”) from that visit or not (“BLQ”). Drug level testing was conducted through week 72. Bars indicate 1 standard error. The table below the axis gives the number of participants per group with lipid results available in each visit window. Multiple results by individuals in windows were averaged. x-axis (panels A–D): weeks since randomization. y-axis (panel A): median percent change in total cholesterol from baseline. y-axis (panel B): median percent change in LDL-C from baseline. y-axis (panel A): median percent change in HDL-C from baseline. y-axis (panel D): median percent change in triglycerides from baseline. Abbreviations: BLQ, below the level of quantitation; FTC, emtricitabine; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Lipid effects were statistically significant when visits with plasma drug detected were compared to the placebo group. Median percent changes (SE) at week 24 for visits with plasma drug detected on TDF/FTC vs placebo were −7.5% (1.5%) vs −1.1% (1.2%), P < .001 for total cholesterol; −7.9% (1.8%) vs 0.0 (1.3%), P < .001 for LDL-C; and −7.7% (2.0%) vs 0.0% (1.4%), P = .002 for HDL-C, respectively. On the absolute scale, the changes (on TDF/FTC with TFV detected vs placebo, respectively) at week 24 translated to −11.6 mg/dL (2.3) vs −1.9 (1.8), P = .001 for total cholesterol; −7.3 mg/dL (1.7) vs 0.0 (1.3), P < .001 for LDL-C; and −3.9 mg/dL (0.9) vs 0.0 (0.5), P < .001 for HDL-C, respectively. The results for non–HDL-C were similar to those for LDL-C. On placebo, 20% ever had HDL-C levels <40 mg/dL compared to 26% on TDF/FTC (P = .17). HDL-C values <40 mg/dL were not more common among those with drug detected (P = .18; detected vs placebo).

At week 48, the HDL-to-cholesterol ratio tended to be increased more on TDF/FTC +5.7 (2.1) than placebo +0.13 (2.2), but the difference was not significant (P = .07) and there was no trend at other time points. There were no significant changes in triglyceride values (Figure 4D, Supplementary Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Short-term metabolic effects of TDF in HIV-uninfected persons have been previously reported [27]. Here, we report the first long-term metabolic evaluation of TDF/FTC in healthy, HIV-uninfected persons against a blinded placebo.

We found modest cholesterol-lowering effects of TDF/FTC. While ARVD switch studies have found decreases with substitution of TDF [15–20], initiation studies found no decrease in lipids with starting a TDF/FTC–based regimen [15]. In 2 randomized studies, addition of TDF to existing stable regimens in persons with dyslipidemia decreased total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol over 12 weeks [28, 29]. The magnitude of our observed cholesterol decreases, even after correcting for adherence, appears smaller than previously reported, and the clinical significance of these changes is unclear, particularly given their transient nature. Unlike many studies in HIV-infected persons [15–20], we found no decrease in triglycerides (TGs) with TDF/FTC. However, TG decrease with TDF was not seen in healthy volunteers [27] or in placebo-controlled studies of HIV-positive persons on a suppressive regimen [28, 29]. This may suggest that reductions in TGs may be related to improved virologic control rather than a direct effect of TDF. The observed reductions in cholesterol are also of interest given the modest increases in lipids seen in HIV-infected persons who initiate or switch to regimens that contain tenofovir alafenamide, which some have speculated may be attributable to the absence of high plasma TDF concentrations [30–32].

Weight increased in the placebo group and decreased transiently in the TDF/FTC group. Modest weight gain is expected in healthy populations throughout early adulthood [33, 34], and the selective accumulation of adipose tissue is striking. Unfortunately, we lack dietary or physical activity data on our participants. The apparently suppressive effect of TDF/FTC on fat accumulation in the early stages of treatment could not be explained by transient nausea and requires further study.

The DXA scans demonstrate that LBM appears unaffected by TDF/FTC and that total weight differences are driven by changes in fat. There was clear gain of fat mass in association with weight gain in the placebo group, whereas it appears that TDF/FTC may lead to a short-term decrease in weight and fat mass. Fat loss with TDF/FTC appears to occur proportionally between trunk and limbs. Further, the effect is transient even at visits with drug detected, so falling adherence is a less likely explanation. Overall, our data provide no evidence of selective peripheral fat loss. However, with few scans after week 48, long-term trends are difficult to discern. The data do not suggest that fat loss is associated with the transient nausea reported with TDF/FTC. Our DXA results do not allow assessment of more subtle fat changes such as changes in facial fat or subcutaneous vs visceral abdominal fat.

Differences in body fat and lipids between groups became more pronounced when plasma drug detection was considered. At week 24, intracellular levels of TFV-DP were also tested. Quantitative TFV-DP levels at week 24 were not significantly more associated with metabolic parameters than plasma detection at week 24. In previous work, TFV-DP was tightly associated with HIV seroconversion risk [23] and bone mineral density [22]. The lack of a quantitative association of metabolic changes with TFV-DP suggests that daily use of TDF/FTC may not lead to larger body composition or lipid changes (Supplementary Table 3).

Leading concerns for TDF/FTC PrEP uptake in populations have been side effects and long-term toxicity [21]. Body composition changes from some ARVDs have been shown to be stigmatizing in ways that inhibit adherence and uptake [16], and dyslipidemia can elevate the risk of cardiovascular disease [14]. TDF/FTC has not been linked with these phenomena; however, these data provide additional reassurance on the modest, apparently benign, and possibly transient metabolic effects of TDF/FTC as PrEP. However, our cohort is limited to a relatively young MSM/TGW population over a 1- to 2-year period. Longer-term effects in older populations merit further evaluation.

Taken together, these results in a healthy seronegative population are consistent with results of randomized antiretroviral initiation [15] and switch studies [16–20], suggesting that TDF has no selective effect on regional fat distribution and leads to modest decreases in lipids.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. Lima: Javier Lama, Lorena Vargas, Jorge Sanchez, Pedro Gonzales; Chiang Mai: Pongpun Saokhieo, Namgwomprom Sirianong; San Francisco: Albert Liu, Kerry Murphy, Hailey Gilmore, Sally Holland, Elizabeth Faber, John Duda; Cape Town: Linda Bewerunge, Elizabeth Batist, Christine Hoskin, Ben Brown; Rio de Janeiro: Carina Beppu-Yoshida, Marcellus Dias da Costa, Sergio Carlos Assis de Jesus Jr, Jose Roberto Grangeiro da Silva, Roberta Millan, Brenda Regina de Siqueira Hoagland, Nilo Martinez Fernandes, Lucilene da Silva Freitas, Laura Mendonca; University of Colorado: Peter L. Anderson, Lane Bushman, Jia-Hua Zheng, Louis Anthony Guida, Brandon Kline; University of California, San Francisco/Gladstone: Pedro Goicochea, Jonathan Manzo, Robert Hance, Jeff McConnell, Patricia Defechereux, Vivian Levy, Malu Robles; DataFax/Net: Brian Postle; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health (NIH): David Burns; Gilead: James Rooney. We are deeply grateful for the participants of the iPrEx study. Study medication was donated by Gilead Sciences.

Financial support. This work was supported by the NIAID (U01 AI106499, UM1 AI068619, U01 AI064002, R03 AI120819, R03 AI122908). Some infrastructure support at the University of California, San Francisco, was provided by an award from the NIH/National Academy for Advancing Translational Science (UL1 TR000004). The iPrEx studies were sponsored by the NIH with cofunding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Gilead Sciences supported travel expenses for non-US investigators to attend study meetings.

Potential conflicts of interest. R. M. G. has received fees from and a research grant from ViiV, a manufacturer of an investigational compound being investigated for use as PrEP. D. V. G. and M. S. have received fees from Gilead Sciences. P. L. A. has received a research grant from Gilead Sciences. All other authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. ; Partners PrEP Study Team Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. ; TDF2 Study Group Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. ; Bangkok Tenofovir Study Group Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013; 381:2083–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Molina JM, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. ; ANRS IPERGAY Study Group On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:2237–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016; 387:53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hosek SG, Rudy B, Landovitz R, et al. ; Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) for HIVAIDS Interventions An HIV preexposure prophylaxis demonstration project and safety study for young MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74:21–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal- and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Intern Med 2016; 176:75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:1601–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lal L, Audsley J, Murphy D, et al. Medication adherence, condom use and sexually transmitted infections in Australian PrEP users: interim results from the Victorian PrEP Demonstration Project. AIDS 2017; 31:1709–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koechlin FM, Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, et al. Values and preferences on the use of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among multiple populations: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav 2017; 21:1325–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mallewa JE, Wilkins E, Vilar J, et al. HIV-associated lipodystrophy: a review of underlying mechanisms and therapeutic options. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 62:648–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grinspoon S, Carr A. Cardiovascular risk and body-fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:48–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, et al. ; 903 Study Group Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA 2004; 292:191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ribera E, Paradiñeiro JC, Curran A, et al. Improvements in subcutaneous fat, lipid profile, and parameters of mitochondrial toxicity in patients with peripheral lipoatrophy when stavudine is switched to tenofovir (LIPOTEST study). HIV Clin Trials 2008; 9:407–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madruga JR, Cassetti I, Suleiman JM, et al. ; Study 903E Team The safety and efficacy of switching stavudine to tenofovir df in combination with lamivudine and efavirenz in hiv-1-infected patients: three-year follow-up after switching therapy. HIV Clin Trials 2007; 8:381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Milinkovic A, Martinez E, López S, et al. The impact of reducing stavudine dose versus switching to tenofovir on plasma lipids, body composition and mitochondrial function in HIV-infected patients. Antivir Ther 2007; 12:407–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fisher M, Moyle GJ, Shahmanesh M, et al. ; SWEET (Simplification With Easier Emtricitabine Tenofovir) Group UK A randomized comparative trial of continued zidovudine/lamivudine or replacement with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine in efavirenz-treated HIV-1-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51:562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moyle GJ, Sabin CA, Cartledge J, et al. ; RAVE (Randomized Abacavir versus Viread Evaluation) Group UK A randomized comparative trial of tenofovir DF or abacavir as replacement for a thymidine analogue in persons with lipoatrophy. AIDS 2006; 20:2043–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013; 27:248–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mulligan K, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, et al. ; Preexposure Prophylaxis Initiative Study Team Effects of emtricitabine/tenofovir on bone mineral density in HIV-negative persons in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:572–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. ; iPrEx Study Team Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:151ra125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koenker R. Quantile regression. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, et al. Regression methods in biostatistics. Boston, MA: Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. StataCorp. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Randell PA, Jackson AG, Zhong L, Yale K, Moyle GJ. The effect of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on whole-body insulin sensitivity, lipids and adipokines in healthy volunteers. Antivir Ther 2010; 15:227–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tungsiripat M, Kitch D, Glesby MJ, et al. A pilot study to determine the impact on dyslipidemia of adding tenofovir to stable background antiretroviral therapy: ACTG 5206. AIDS 2010; 24:1781–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Santos JR, Saumoy M, Curran A, et al. ; Tenofovir/emtricitabine inflUence on LIPid metabolism (TULIP) Study Group The lipid-lowering effect of tenofovir/emtricitabine: a randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. ; GS-US-292-0104/0111 Study Team Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet 2015; 385:2606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mills A, Arribas JR, Andrade-Villanueva J, et al. ; GS-US-292-0109 team Switching from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate to tenofovir alafenamide in antiretroviral regimens for virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1 infection: a randomised, active-controlled, multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016; 16:43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Post FA, Tebas P, Clarke A, et al. Brief report: switching to tenofovir alafenamide, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, in HIV-infected adults with renal impairment: 96-week results from a single-arm, multicenter, open-label phase 3 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74:180–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gordon-Larsen P, Hou N, Sidney S, et al. Fifteen-year longitudinal trends in walking patterns and their impact on weight change. Am J Clin Nutr 2009; 89:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheehan TJ, DuBrava S, DeChello LM, Fang Z. Rates of weight change for black and white Americans over a twenty year period. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003; 27:498–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.