Abstract

The N-terminally myristoylated matrix domain (MA) of the HIV-1 Gag polyprotein promotes virus assembly by targeting Gag to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (PM). Recent studies indicate that, prior to membrane binding, MA associates with cytoplasmic tRNAs (including tRNALys3), and in vitro studies of tRNA-dependent MA interactions with model membranes have led to proposals that competitive tRNA interactions contribute to membrane discrimination. We have characterized interactions between native, mutant, and unmyristylated (myr-) MA proteins and recombinant tRNALys3 by NMR spectroscopy and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). NMR experiments confirm that tRNALys3 interacts with a patch of basic residues that are also important for binding to the plasma membrane marker, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, [PI(4,5)P2]. Unexpectedly, the affinity of MA for tRNALys3 (Kd = 0.63 ± 0.03 μM) is approximately one order of magnitude greater than its affinity for PI(4,5)P2 enriched liposomes (Kd(apparent) = 10.2 ± 2.1 μM), and NMR studies indicate that tRNALys3 binding blocks MA association with liposomes, including those enriched with PI(4,5)P2, phosphatidylserine (PS), and cholesterol. However, the affinity of MA for tRNALys3 is diminished by mutations or sample conditions that promote myristate exposure. Since Gag-Gag interactions are known to promote myristate exposure, our findings support virus assembly models in which membrane targeting and genome binding are mechanistically coupled.

Keywords: HIV, Matrix Protein, tRNA, Membrane, Liposomes

Introduction

Assembly of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) particles proceeds via co-localization of two copies of the viral genome and a small number of viral Gag polyproteins (~2 dozen copies or fewer) to puncta on the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (PM) [1–6]. Subsequent association of additional Gag proteins (~2,400 proteins [7]) and cellular ESCRT protein sorting factors leads to vesiculation and budding of new immature particles [3, 7–9]. Membrane anchoring is mediated by Gag’s N-terminally myristolyated matrix domain (MA) [10–12]. Mutations that block myristoylation inhibit membrane binding in vitro, and N-terminal acylation by unsaturated fatty acids disrupts Gag trafficking to the plasma membrane [12]. Conserved Lys and/or Arg residues that are clustered on the surface of MA are also important for membrane selection and binding [13–15]. In addition, several studies have shown that membrane binding is promoted by Gag self-association [11]. Mutations in the capsid (CA) and downstream SP1 domains of Gag that inhibit Gag assembly disrupt membrane binding [16–18], and sequentially-incremented C-terminal truncations of Gag result in progressive decreases in Gag multimerization and membrane affinity [19]. The nucleocapsid domain (NC) of Gag, which functions in viral genome selection and packaging, also appears to play a role in membrane binding by promoting Gag-Gag interactions upon binding to the viral RNA [20–22]. In support of this hypothesis, chimeric Gag-like and MA-containing constructs containing non-native multimerization domains exhibit high affinities for binding to membranes in both in vitro and cellular assays [23]. Thus, the primary viral determinants of membrane targeting appear to be the N-terminal myristoyl moiety and basic surface patch of MA, coupled with NC’s RNA-dependent ability to promote myristate exposure via a Gag-Gag mediated entropic myristoyl switch mechanism [24].

A major cellular determinant of membrane targeting is phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], an acidic PM constituent that normally functions in the targeting of cellular proteins to the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane [25]. Depletion of cellular PI(4,5)P2 inhibits PM targeting and viral budding, and over-expression of PI(4,5)P2 in endosomal membranes retargets virus assembly to endosomes [26]. The HIV-1 envelope is enriched not only in PI(4,5)P2, but also in cholesterol and acidic phospholipids, including phosphatidylserine (PS), leading to proposals that Gag is either targeted to raft-like microdomains or induces their formation upon membrane binding [27–35] (reviewed in:[34, 36–39]). NMR and computational studies indicate that PI(4,5)P2 and PS bind specifically to the conserved basic surface patch on MA (see above) [40, 41]. Thus, studies collectively indicate that membranes (or membrane patches) enriched in PI(4,5)P2, cholesterol, and acidic phospholipids serve as the primary cellular determinants of membrane targeting by Gag.

Recently, CLIP studies revealed that MA also interacts with cytoplasmic tRNAs [42], including the tRNALys3 isoform that is packaged into virions and serves as the primer for reverse transcription [42–45]. Although a biological function for MA-tRNA binding has not been established genetically, in vitro membrane binding assays indicate that RNA interactions with MA may be important for both genome and membrane selectivity. In particular, in vitro and cell-based studies have indicated that RNAs bound to MA can inhibit the binding of Gag to PS-enriched membranes, but not to PI(4,5)P2 enriched membranes [46–49]. In addition, tRNAs were found to inhibit binding of MA to liposomes in a lipid- and salt-dependent manner, with multimeric MA and Gag-like constructs exhibiting higher affinity for membranes than monomer MA [23]. Additional recent studies found that tRNAs at micromolar concentrations can inhibit the binding of Gag constructs to membranes, and that binding inhibition can be overcome by addition of viral genome [50]. These findings collectively suggest that tRNA-MA interactions may be important for preventing premature PM binding or aberrant targeting to internal membranes.

To further explore the role of MA-tRNA interactions on membrane targeting, we examined interactions of native, mutant, and unmyristoylated (myr(-)) forms of the HIV-1 MA protein with recombinant tRNALys3 using NMR and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Residues that interact directly with tRNALys3 were identified, and the relative abilities of liposomes with different lipid compositions and tRNALys3 to bind competitively with MA were also determined. Our studies confirmed proposals that tRNALys3 competes for basic MA surface residues known to be important for membrane binding, and that tRNALys3 inhibits MA binding to liposomes. Unexpectedly, we also found that tRNALys3 inhibits the binding of MA to liposomes containing virus-like lipid compositions, including PI(4,5)P2, and that myristate exposure diminishes the affinity of tRNA for MA. Our findings support a virus assembly process in which membrane binding is dependent on tRNA release, with both processes promoted by a genome binding-triggered Gag-Gag mediated myristoyl switch mechanism.

Results

Stoichiometric binding of tRNALys3 to MA

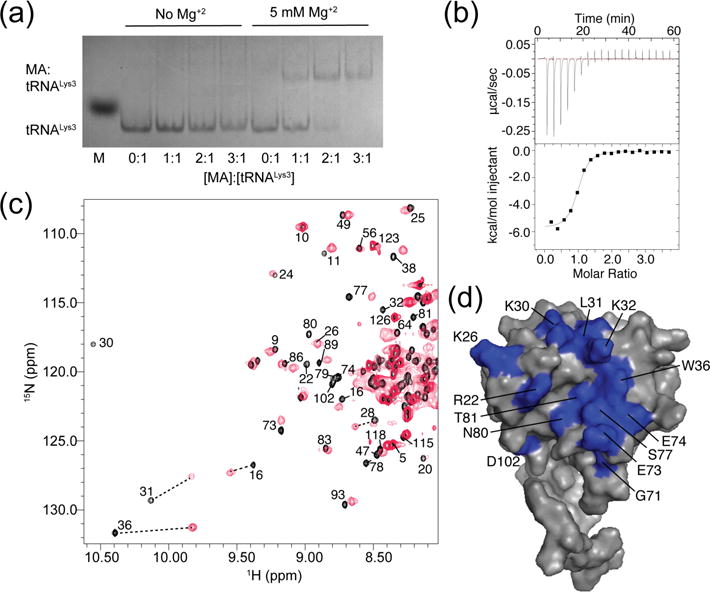

Of the eight tRNAs that predominately bound to the MA domain of Gag in CLIP studies [42], tRNALys3 was selected for quantitative studies due to its well documented role in priming reverse transcription. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) conducted initially with commercially available E. coli tRNALys exhibited a well-defined, concentration-dependent band consistent with the stoichiometric formation of a 1:1 E. coli tRNALys:MA complex (Supplementary Fig. S1). In initial studies, we were unable to observe similar behavior for recombinant tRNALys3 that was prepared and purified in our lab using a T7 RNA polymerase-based approach [51, 52], Fig. 1a. Both RNAs were incubated with MA under physiological-like conditions of ionic strength (PI = 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5), and gels were run using a standard Tris-Borate running buffer that lacked Mg+2. E. coli tRNALys3 contains several modified bases that are known to stabilize tRNA structure [43, 53, 54] and could potentially directly participate in MA binding. To test these possibilities, we conducted electrophoresis experiments using electrophoresis conditions in which Mg+2 was added to the running buffer (TBM), which is known to stabilize Mg+2-dependent complexes [55]. Under these conditions, the E. coli and T7-generated tRNALys3 RNAs exhibited similar MA binding behavior, indicating that the RNA modifications promote MA binding by stabilizing the folding of the RNA. ITC was then used to characterize the thermodynamics of the interaction between recombinant tRNALys3 and HIV-1 matrix. As observed by EMSA, stoichiometric 1:1 binding was observed (n = 0.89 ± 0.06; Kd = 0.63 ± 0.03 μM at pH 7.0) (Table 1; Fig. 1b). Binding is primarily enthalpy-driven at 30°C (ΔH = −5.9 ± 0.4 kcal/mol, ΔS = 8.9 ± 1.3 cal/mol/deg), consistent with an electrostatic binding mode.

Figure 1.

(a) EMSA data showing that Mg2+ is essential for stabilizing the tRNALys3 structure and allowing MA binding. (b) Representative ITC data showing that tRNALys3 interacts in a 1:1 ratio with MA (Kd of 0.63 ± 0.3 μM). (c) 1H-15N HSQC spectra for myr(-)MA in the absence (black) and presence (red) of a stoichiometric amount of tRNALys3. (d) Map of residues of myr(-)MA (PDB entry 2H3F [83]) that shifted or broadened significantly upon binding to tRNALys3.

Table 1.

Thermodynamic characterization of MA mutants with tRNALys3

| Kd (μM) | n | ΔH (kcal/mol) | ΔS (cal/mol/deg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | −5.9 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 1.3 |

| K30A | 2.51 ± 0.19*** | 1.09 ± 0.16 | −6.1 ± 0.8 | 5.6 ± 2.8 |

| K30T | 19 ± 4** | 0.96 ± 0.06 | −4.2 ± 0.6* | 7.8 ± 2.4 |

| K18/30T | 17.3 ± 0.9*** | 0.96 ± 0.02 | −4.3 ± 0.2** | 7.6 ± 0.7 |

| K18T | 0.84 ± 0.09* | 0.90 ± 0.04 | −7.3 ± 0.6* | 3.7 ± 2.1* |

| K32A | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| K32T | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D |

| K26T | 3.2 ± 0.6** | 0.87 ± 0.03 | −5.2 ± 0.3* | 8.1 ± 1.0 |

| K27T | 9.4 ± 1.0*** | 0.91 ± 0.05 | −5.15 ± 0.01* | 6.0 ± 0.2* |

| K26/27T | N/D | N/D | N/D | N/D |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

tRNALys3 binds to the conserved basic patch on MA

Heteronuclear spin quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments were utilized to identify residues on MA that interact with tRNALys3 (Fig. 1c,d). Experiments with the myristoylated MA protein and tRNALys3 resulted in peak broadening due to an intermediate exchange regime. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments indicated that MA and an unmyristoylated mutant [myr(-)MA] had similar binding profiles at pH 7.0, indicating similar binding sites when the myristoyl group is fully sequestered (Fig. 4a). By lowering the pH and using myr(-)MA, the RNA-protein interaction shifted into slow exchange. Residues affected by tRNALys3 binding are near the basic patch of the molecule, indicating that tRNA may compete for a similar binding site as PI(4,5)P2. In particular, residues K26, K30 and K32 shift upon binding to tRNALys3. These residues play a known role in targeting MA to the plasma membrane for viral assembly [13–15, 41, 48, 56]. R22 was also shifted upon tRNA binding, along with residues near the N-termini of helices II and V and the C-terminus of helix I that reside near the basic patch of MA. Thus, the NMR data indicate that tRNA binds to the conserved basic patch of MA.

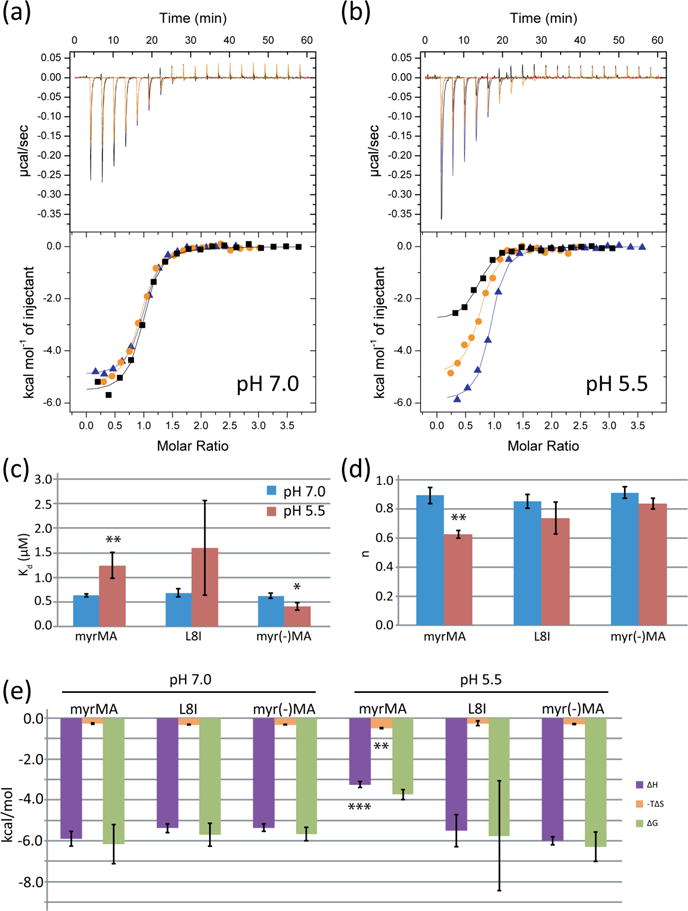

Figure 4.

Myristoyl group exposure weakens tRNA-MA interactions. (a) WT myr(MA) (black), the exposure-deficient mutant L8I (orange), and myr(-)MA (blue) have similar binding profiles for tRNALys3 at pH 7.0. (b) ITC titration curves at pH 5.5, when equilibrium of the myristoyl group shifts to the exposed conformation. (c) Kd values for the MA myristoylation mutants at pH 7.0 (blue) and pH 5.5 (red). (d) Stoichiometries for the myristoylation mutants at pH 7.0 (blue) and pH 5.5 (red). (e) Thermodynamic profiles for MA myristoylation mutants at pH 7.0 and pH 5.5 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

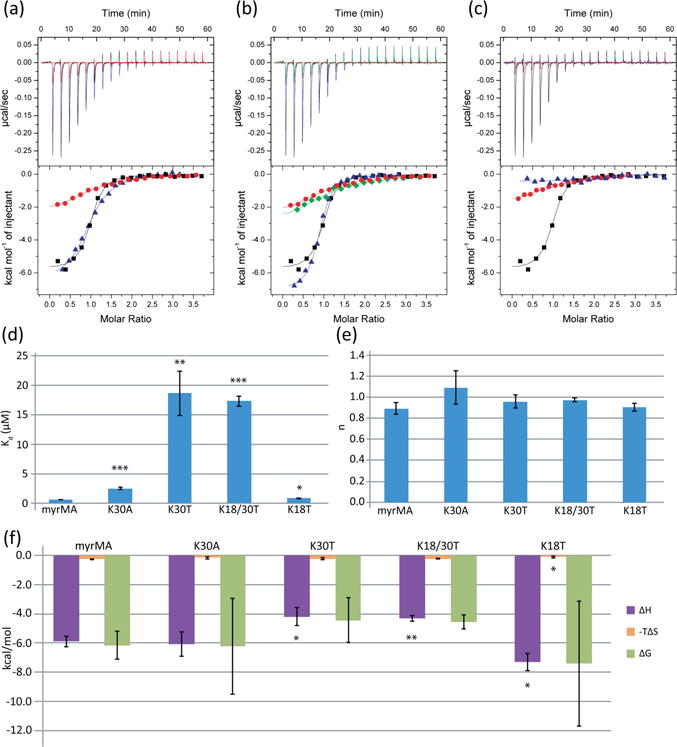

Mutation of basic patch residues (K18T, K18/30T, and K30/32T) can decrease MA’s ability to bind PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes [15, 41, 48], and mutations affecting K30 and K32 retarget assembly of Gag from the plasma membrane to multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and reduce virus release efficiency [13, 15, 26, 41, 56]. To determine if these residues are also involved in tRNALys3 binding, we mutated K18, K30, and K32 (Fig. 2). K30A decreased MA’s affinity for tRNALys3, but K30T had a much greater effect (wt: Kd = 0.63 ± 0.03 μM; K30A: Kd = 2.51 ± 0.19 μM, p < 0.001; K30T: Kd = 19 ± 4 μM, p = 0.001) (Fig. 2a,d, Table 1). The enthalpy associated with tRNA binding did not significantly change for the K30A mutant compared to the wild type protein (wt: ΔH = −5.9 ± 0.4 kcal/mol, K30A: ΔH = −6.1 ± 0.8 kcal/mol, p = 0.75), but the enthalpy of reaction increased for the K30T mutant (ΔH =−4.2 ± 0.6, p = 0.015) (Fig. 2f). Despite the change in enthalpy, the entropy of the reaction did not change for either of the mutants (wt: ΔS = 8.9 ± 1.3 cal/mol/deg; K30A: ΔS = 5.6 ± 2.8 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.14; K30T: ΔS = 7.8 ± 2.4 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.51). The enthalpy-dependent weakening of the interaction cannot be attributed to charge loss alone, as both the K30A and K30T mutants replaced a positive charge from the basic patch with a neutral residue. The mutations did not affect the stoichiometry, as the reaction retained its 1:1 binding ratio (wt: n = 0.89 ± 0.06, K30A: n = 1.09 ± 0.16, K30T: n = 0.96 ± 0.06) (Fig. 2e). Notably, the K32T and K32A single point mutants abolished binding to tRNALys3, indicating that this residue is essential to MA’s ability to bind tRNALys3 (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2.

Mutations that disrupt MA-membrane interactions also weaken MA’s affinity for tRNA. (a) ITC titration curves of K30A (blue) and K30T (red) mutants compared to wild type MA (black). (b) Titration curves comparing K18T (blue) mutant, K30T mutant (red), and the K18T/K30T double mutant (green). (c) ITC data for the K32A (blue) and K32T (red) mutants. (d) Graph of Kd values for K18 and K30 mutants. K32 mutants did not bind and are not included in this graph. (e) Graph of the stoichiometry values (n) determined by ITC. (f) Thermodynamic profiles of the K18 and K30 mutants (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

A K18T mutation had the smallest effect of the mutants characterized, resulting in a slight weakening of tRNALys3-MA binding (Kd = 0.84 ± 0.9 μM, p = 0.018) (Fig. 2b). Unlike K30T, the K18T mutant decreased the enthalpy of the reaction (ΔH =−7.3 ± 0.6 kcal/mol, p = 0.02), as well as significantly decreased the entropy of the reaction (ΔS = 3.7 ± 2.1 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.02) (Fig. 2f). A decrease in affinity was seen for K18/30T (Kd = 17.3 ± 0.9 μM), but this is not significantly different to the decrease seen for the K30T single mutant (p = 0.58) (Fig. 2d). K18/30T exhibited binding enthalpy and entropy (ΔH =−4.3 ± 0.2 kcal/mol, ΔS = 7.6 ± 0.7 cal/mol/deg) similar to those of K30T, suggesting that most of the observed differences result from the K30T mutation.

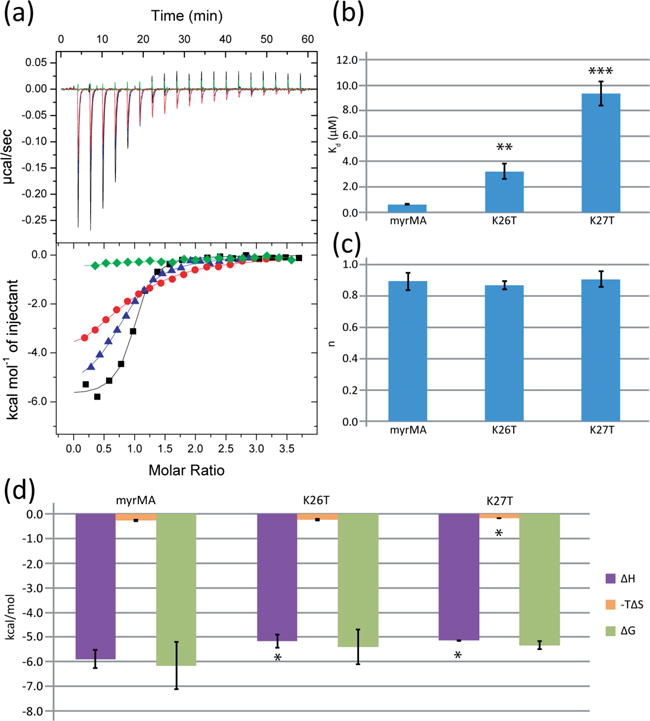

We also examined the potential roles of basic residues K26 and K27 on tRNA binding. K27T had a greater effect than K26T, with a Kd of 9.4 ± 1.0 μM and 3.2 ± 0.6 μM, respectively (Fig. 3a,b; Table 1). Binding between K26T and K27T MA mutants and tRNALys3 remained at a 1:1 binding ratio (n: wt = 0.89 ± 0.06, K26T = 0.87 ± 0.03, K27T = 0.91 ± 0.05) (Fig. 3c). Both mutations exhibited similar, slight increases in enthalpy of the reaction (K26T: ΔH =−5.2 ± 0.3 kcal/mol, p = 0.05, K27T: ΔH =−5.2 ± 0.01, p = 0.02) but only the K27T mutant exhibited a decrease in the entropy (K26T: ΔS = 8.1 ± 1.0 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.43, K27T: ΔS = 6.0 ± 0.2 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.02) (Fig. 3d). A cumulative effect of the mutations may be responsible for the phenotype seen in Chukkapalli et al., where the K26/27T double mutant was unable to discriminate between membranes that contained or lacked PI(4,5)P2, bound promiscuously to negatively charged liposomes [48]. Consistent with those observations, we found that the K26/27T double mutant was unable to bind with significant affinity to tRNALys3.

Figure 3.

Mutations known to affect membrane specificity also decrease MA’s affinity for tRNA. (a) ITC data for the K27T (red), K26T (blue) and K26T/K27T (green) MA mutants. (b) Graph of binding affinities for K26 and K27 mutants. (c) Stoichiometries for K26T and K27T mutants compared to wild type MA. (d) Thermodynamic profile for the K26T and K27T mutants (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Myristoyl group exposure inhibits tRNALys3 binding

In the absence of membranes, the myristoyl group of both the MA protein and MA-CA constructs exists in equilibrium between the sequestered and exposed conformations [24, 57–59]. The equilibrium position can be shifted toward the exposed conformation upon decreasing the sample pH, which favors an internal salt bridge between the side chains of His89 and Glu12, or by increasing the concentration of MA, which promotes MA-MA interactions [24, 59]. To determine if myristate exposure influences tRNALys3 binding, we compared the binding of MA to tRNALys3 at pH 7.0 and pH 5.5. Titrations with an unmyristoylated construct [myr(-)MA)] and an exposure-deficient mutant (L8I) [60, 61] at neutral and low pH were also performed. At pH 7.0, where the wild-type protein strongly favors the myristoyl-sequestered conformation, there was no significant difference in stoichiometry or affinity among the native and mutant proteins (n: wt = 0.89 ± 0.06, L8I = 0.85 ± 0.05, myr(-)MA = 0.91 ± 0.04; Kd: wt = 0.63 ± 0.03 μM, L8I = 0.68 ± 0.08 μM, myr(-)MA = 0.62 ± 0.05 μM) (Fig 4a,c,d, Table 2). However, at pH 5.5, where the equilibrium shifts toward the myristoyl-exposed conformation [24, 59], a decrease in apparent stoichiometry was observed (n: wt = 0.62 ± 0.03, L8I = 0.74 ± 0.11, myr(-)MA = 0.83 ± 0.04) (Fig. 4b,d). We interpret this as resulting from an inability of the myristoyl-exposed conformer to bind tightly to tRNALys3, resulting in a concomitant reduction in the amount of protein in the myr-sequestered conformation available for tRNA binding. Myristoyl exposure also led to a significant decrease in apparent affinity at pH 5.5 for the wild type protein (wt: Kd = 1.2 ± 0.3 μM, p = 0.001, L8I: Kd = 1.6 ± 1.0 μM, p = 0.20, myr(-)MA: Kd = 0.41 ± 0.08 μM, p = 0.01) (Fig. 4c). The enthalpy of the reaction was similar for both of the mutants at both pH 7.0 and 5.5, but the enthalpy of the reaction increased for the wild type protein when the pH was decreased to 5.5 (ΔH =−3.25 ± 0.14 kcal/mol). The same held true for the entropy of the reaction, with only MA at pH 5.5 significantly deviating from the results of the wild type protein at pH 7.0 (ΔS = 16.3 ± 0.8 cal/mol/deg, p = 0.001) (Fig. 4e).

Table 2.

Characterization of myristoyl group interactions with tRNALys3

| Kd (μM) | n | ΔH (kcal/mol) | ΔS (cal/mol/deg) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA pH 7.0 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.89 ± 0.06 | −5.9 ± 0.4 | 8.9 ± 1.3 |

| L8I pH 7.0 | 0.68 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | −5.4 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.9 |

| myr(-)MA pH 7.0 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | −5.4 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 0.5 |

| MA pH 5.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3** | 0.62 ± 0.03** | −3.25 ± 0.14*** | 16.3 ± 0.8** |

| L8I pH 5.5 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 0.74 ± 0.11 | −5.5 ± 0.8 | 8.7 ± 3.9 |

| myr(-)MA pH 5.5 | 0.41 ± 0.08* | 0.83 ± 0.04 | −6.0 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 1.0 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

p<0.001

tRNA inhibits MA binding to liposomes

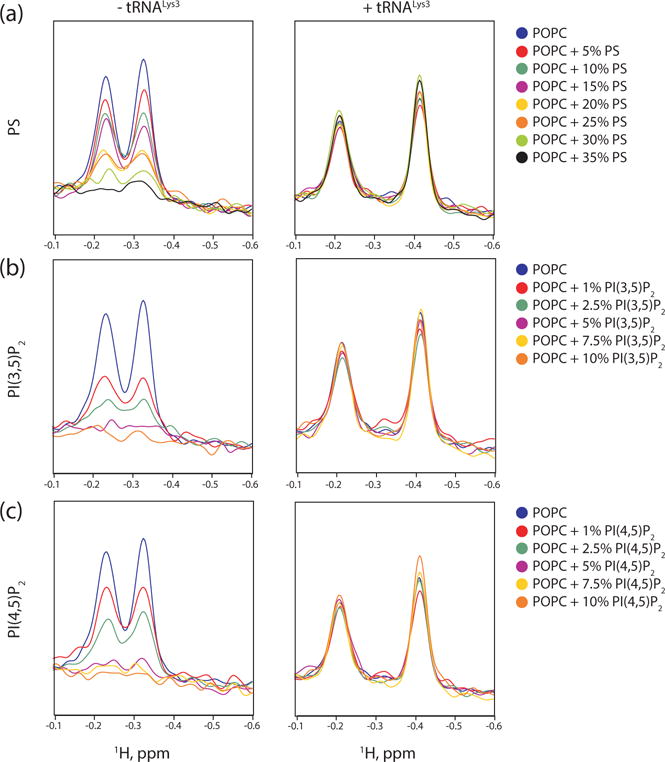

1D NMR liposome titration experiments were employed to probe the influence of tRNALys3 on the ability of MA to bind liposomes [41]. Unlike previous NMR liposome studies, we could not use the structured protein amide region of the spectra due to overlap with RNA signals. We instead used the upfield signals of the methyl groups for I34 and L21, the latter of which is located in the basic patch and exhibits an upfield shift upon binding to RNA. In the absence of tRNA, MA bound indiscriminately to negatively charged membranes, with increased membrane binding correlating with increasing negative charge on the liposomes. As the concentration of phosphatidylserine (PS) in the liposomes increased, a higher percentage of MA bound, with most of the protein bound at a PS composition of 35% (Fig 5a). tRNALys3 prevented binding to PS-containing liposomes, including those with high concentrations of PS similar to physiological concentrations of the inner leaflet [32, 62, 63], consistent with the hypothesis that tRNA regulates MA’s ability to discriminate between membranes. A similar phenomenon occurred with liposomes containing phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate [PI(3,5)P2] (Fig. 5b), a lipid with a similar charge as PI(4,5)P2 that is found in intercellular membranes at low concentrations during times of osmotic stress [64].

Figure 5.

Negative phospholipids, including PI(4,5)P2 cannot outcompete tRNALys3. (a) 1D 1H NMR spectra of MA titrated with liposomes containing increasing amount of PS in the absence (left) and presence (right) of tRNALys3. (b) 1H-1D NMR spectra of MA titrated with liposomes containing increasing amount of PI(3,5)P2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of tRNALys3. (c) 1H-1D NMR spectra of MA titrated with liposomes containing increasing amount of PI(4,5)P2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of tRNALys3.

If tRNA allows MA to discriminate between membranes because PI(4,5)P2 outcompetes tRNA for the basic patch, MA should bind to PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes in both the presence and the absence of tRNA. tRNA exists in a channeled life cycle and rarely exists in free form in the cell [65], making determination of the correct concentration of tRNA to use difficult. We selected a 1.2:1 molar ratio of tRNALys3:MA for our experiments that allowed full saturation of MA with tRNALys3, as mixtures of bound and unbound MA made interpretation of the 1D NMR spectra more difficult. This was less than the 2:1 ratio used in other works to see a 50% reduction in membrane binding in Gag, although their effective concentration of MA-binding tRNA may be lower than 2:1 as they used yeast total tRNA [50]. Titrating PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes into MA in the absence of tRNA resulted in a titration curve similar to that of PI(3,5)P2-containing liposomes (Fig. 5c). However, we found that when saturated with tRNALys3, MA does not readily bind to PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes. tRNALys3 outcompeted the liposomes not just at physiologically relevant concentrations of PI(4,5)P2, but at concentrations far higher than would occur in a cell [33, 66] and those found enriched in HIV-1 virions [33]. As a potential negative control, liposome binding experiments were also conducted with tRNAIleGAU, which was not strongly associated with MA in the CLIP studies [42]. Surprisingly, this tRNA also inhibited MA binding to PI(4,5)P2 enriched liposomes. Subsequent ITC studies revealed that the affinity and stoichiometry of tRNAIleGAU for MA is similar to that of tRNALys3 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Although this explains why tRNAIleGAU can inhibit MA binding to liposomes, it is unclear to us why significant binding was not observed in the CLIP studies. We were unable to detect differences in liposome binding at pH 7.0 and 6.5 (using 5% PI(4,5)P2 liposomes), most likely due to insufficient sensitivity of our method and a relatively small shift in population toward the myristate exposed state at pH 6.5. Liposome instability precluded measurements at lower pH values were myristate exposure would be favored.

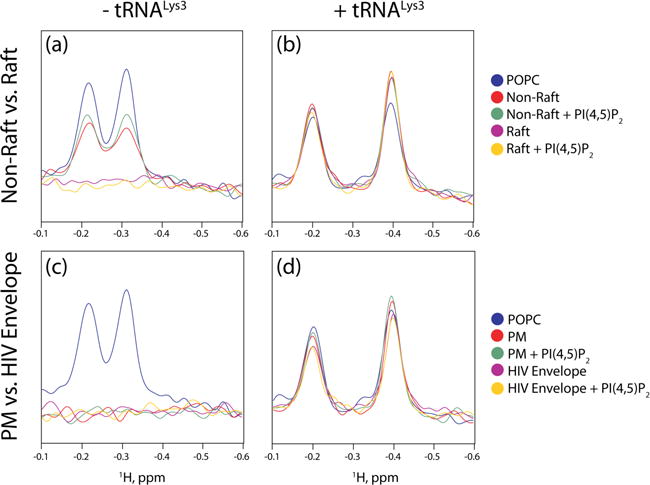

Evidence suggests that Gag assembles at raft-like microdomains enriched in cholesterol [27–31] and that the HIV-1 lipid envelope has a raft-like composition [32, 67]. Previous studies in our lab used model membranes with plasma membrane compositions mimicking the raft and non-raft domains of the plasma membrane. These studies found that MA required PI(4,5)P2 to bind to non-raft liposomes, but would bind to raft domains in both the presence and absence of PI(4,5)P2 [41]. We saw similar results in the absence of tRNA (Fig. 6a). However, the presence of tRNALys3 prevented binding to both rafts and non-rafts, even with the addition of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 6b). The previous work took into consideration the composition of rafts and non-rafts as reported in Brügger et al. [32] and Chan et al. [33], but treated cholesterol as a phospholipid when calculating percentages. Because cholesterol inserts into the fatty acid chains, treating it as a phospholipid component may skew the composition of the membranes when accounting for differences in the inner and outer leaflets. In order to confirm the result, liposomes with compositions similar to the plasma membrane of MT4 cells and the lipid envelope of the HIV-1 virus as reported [32] were used as well. Differences in the composition of the inner and outer leaflet due to membrane asymmetry [62, 63, 68] were taken into account, keeping the ratio of cholesterol to phospholipid constant and only adjusting the percentages of the relevant phospholipids. These membranes had increased concentrations of phosphatidylethanolamine and had similar cholesterol concentrations to liposomes used previously. MA bound strongly to both the MT4 plasma membrane model and the HIV-1 envelope model, despite the absence of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 6c). No appreciable increase in binding occurred upon the addition of PI(4,5)P2. However, despite the high negative charge, tRNALys3 still successfully prevented binding to all liposomes, including those with PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

tRNALys3 prevents MA interactions with raft-like liposomes. (a) 1D 1H NMR titration spectra probing Interactions between MA and liposomes with raft and non-raft compositions in the absence of tRNALys3. (b) Interactions between MA and liposomes with raft and non-raft compositions in the presence of tRNALys3. (c) Titration of MA with liposomes approximating the inner leaflet of MT4 cells and the HIV-1 lipid envelope in the absence of RNA. (d) Titration of MA with liposomes approximating the inner leaflet of MT4 cells and the HIV-1 lipid envelope in the presence of tRNA.

Discussion

Recent work suggested that T7-transcibed tRNALys3 does not suppress Gag-membrane interactions in vitro, and that MA had slightly less affinity for tRNALys3 than tRNAPro, the latter of which was not found to predominately bind to MA in CLIP studies and did prevent Gag-membrane binding in liposome flotation assays [69]. Although we observed weak, non-stoichiometric binding in the absence of Mg+2, its inclusion in tRNA samples and in the running buffers of electrophoresis experiments afforded relatively tight, 1:1 binding. These findings are analogous to results obtained upon titration of tRNA with the HIV nucleocapsid protein (NC), a potent nucleic acid chaperone that is capable of unwinding tRNAs in the absence, but not the presence, of tRNA-stabilizing Mg+2 [70]. Thus, our studies indicate that tight, stoichiometric binding of MA to tRNALys3 is dependent on the structure of the RNA, which is stabilized by magnesium [53, 71]. Differences between our findings and earlier work may be due to differences in Mg+2 concentrations and methodologies employed.

Our mutagenesis studies indicate that tRNALys3 binds to the conserved basic patch MA via an enthalpy-driven process, a hallmark of electrostatic interactions. The specific effects of the substitutions varied, however, based on the site and nature of the mutation. The K32A and K32T mutants reduced affinities to the point that thermodynamic parameters could not be reliably determined. Reduced binding enthalpies were observed for the K30T, K18/30T, K26T, and K27T mutants, which removed positive charges from the basic patch. A reduction in binding enthalpy for the K18T mutant was offset by an increase in the entropy of the reaction, resulting in only a slight reduction in binding affinity. Of all of the basic patch mutations, K18T had the smallest effect on tRNALys3 binding. The K18/30T mutant bound tRNALys3 with affinity similar to that of the K30T mutant, indicating little or no additive effects of mutating K18. The K30A mutant weakened the interaction 4-fold, compared to a 30-fold difference for the K30T mutant. The entropy of the reaction did not significantly change for either mutant, indicating that the differences in binding are related to the enthalpy of the reaction. Mutating K30 to the hydrophobic residue alanine did not significantly decrease the enthalpy of the reaction, indicating that the loss of the positive charge is not the main reason for the weakening of the interaction. The electronegative mutation to threonine had a much greater effect on tRNA-MA interactions despite the fact that the mutation was of similar size as the alanine mutation. Threonine is known to form helix caps, and it is conceivable that the K30T mutation perturbs the structure of the protein, in addition to eliminating a critical charged group. Both K26T and K27T mutants weakened the interaction between MA and tRNALys3, with slight increases in enthalpy. The K27T bound much more weakly than K26T, indicating that it plays more of a role in the interaction. However, neither single mutation could abolish binding, unlike the K26/27T double mutant, indicating that these residues act synergistically to promote tRNA binding. In summary, the four lysine resides that appear to be most important for tRNA binding (K26, K27, K30, and K32) form a cluster on the conserved basic patch. These findings, together with the NMR titration data, indicate that tRNALys3 binds to a site near the N-terminus of helix II, at or near the beta-turn where K30 and K32 are located (Fig. 1).

Importantly, the residues found here to be important for tRNA binding were shown previously to play important roles in membrane targeting. Substitution of K32 by Glu or Ala significantly reduces the affinity of MA for PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes and interrupts virus replication [14, 41]. K32 is also the only residue examined in this study that could abolish binding in a single mutation. K30 likewise plays a role in membrane targeting [41], and mutation of residues K18, K30, and K32 all reduce MA’s ability to bind to both PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes and tRNALys3 [48]. The K26/27T double mutant, while also able to retarget Gag to MVBs, has a different phenotype that reduces the specificity of MA for PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes [48]. The K26/27T mutant binds to liposomes of negative charge with a similar affinity as liposomes that contain PI(4,5)P2[48], and this finding is consistent with NMR titration studies indicating that this region of the protein surface functions as the high affinity tRNALys3 binding site.

Our finding that MA uses common residues for both tRNA and membrane binding suggests that membrane binding will require either concomitant or a priori tRNA displacement. In addition, it is conceivable that tRNA association with the membrane binding surface might facilitate discriminative binding to membranes enriched in PI(4,5)P2, PS, and cholesterol. We tested these hypotheses by examining the ability of MA to bind to liposomes with varying lipid compositions. The presence of tRNALys3 prevented MA binding to negatively charged liposomes that lacked PI(4,5)P2, as expected. However, it also prevented binding to liposomes enriched with PI(4,5)P2, cholesterol, and other acidic lipids found in the viral envelope, as well as to liposomes containing high, non-physiologically relevant concentrations of PI(4,5)P2 [33, 66]. tRNAIleGAU was similarly found to prevent binding to PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes. ITC studies with tRNAIleGAU indicated a five-fold weaker affinity for myrMA than tRNALys3 (Kd = 3.41 ± 0.17 μM), and thus could be a nonspecific binder of myrMA of similar size and charge as tRNALys3 (Supplementary Fig. S3). These findings are consistent with quantitative dissociation constants observed here for MA:tRNALys3 and previously for MA binding to liposomes [41]. Thus, the affinity of MA for tRNALys3 (Kd = 0.63 ± 0.03 μM) is 20-fold greater than its apparent affinity for PI(4,5)P2-enriched liposomes (Kd apparent =10.2 ± 2.1 μM) [41]. In vivo, Gag assembles at membranes containing high concentrations of cholesterol, PS, and other acidic phospholipids, in addition to PI(4,5)P2 (so-called “raft-like” membranes) [31–33, 35, 36]. Liposome binding studies have shown that MA requires PI(4,5)P2 to bind to non-raft membranes, but does not require PI(4,5)P2 to bind to raft-like membranes [41]. We were able to replicate those results in the absence of tRNALys3. However, liposomes containing raft-like levels of PS, cholesterol, and other lipids associated with rafts were unable to outcompete tRNALys3, even in the presence of PI(4,5)P2. PI(4,5)P2 has been shown to outcompete RNA for MA that is bound to beads [72, 73], but it remains unclear whether or not the myristoyl is intrinsically exposed in these constructs (see below). Our findings collectively suggest that factors other than membrane composition are required for tRNA displacement and membrane binding.

The binding of MA (and Gag) to membranes is critically dependent on the N-terminal myristoyl moiety, which is capable of adopting sequestered and exposed conformations [24]. As shown here, conditions and/or mutations that promote myristate exposure lead to reduced affinity for tRNALys3. Thus, processes or conditions that promote myristate exposure are likely to tip the binding affinity of MA away from tRNA and toward the membrane. In vitro, myristoyl exposure is favored at lower sample pH, due to stabilization of an internal His89-Glu12 salt bridge [24, 41, 59, 60, 74]. It is thus possible that a pH gradient near the PM [75], or an overall reduction in cytoplasmic pH that appears to occur upon HIV-1 infection [76], may help promote myristate exposure. MA self-association can also promote myristate exposure and membrane binding [11]. Mutations in Gag that disrupt self-association inhibit membrane binding [16–18], and sequentially-incremented C-terminal truncations of Gag lead to progressive decreases in Gag multimerization and membrane affinity [19]. In addition, the NC domain can promote Gag binding to membranes [20–22] by binding cooperatively to nucleic acids templates [77–80], and RNA-promoted Gag assembly has been proposed to promote myristate exposure and thereby enhance the affinity of Gag for membranes. These findings suggest that the ability of RNA to promote Gag binding to liposomes is due to RNA-induced Gag-Gag interactions that entropically promote myristate exposure [24]. In vitro and cell-based studies showing that RNAs bound to MA can inhibit the binding of Gag to PS-enriched membranes, but not to PI(4,5)P2 enriched membranes [46–48], likely reflect the intrinsic self-association properties of Gag relative to MA that favor myristoyl group exposure [24]. Similarly, tRNAs were shown to inhibit binding of MA to liposomes in a lipid- and salt-dependent manner, with multimeric MA and Gag-like constructs exhibiting higher affinity for membranes than monomeric MA [23]. Notably, recent studies with reconstituted systems suggest that tRNA-Gag interactions may regulate genome selection. In these studies, multiple long-chain RNAs were able to induce similar increases in Gag association with membranes in the absence of tRNA, but in the presence of tRNA, the addition of sequences containing the 5 ˈUTR increased membrane binding significantly more than non-UTR containing RNAs [50]. It is possible that genome binding promotes the multimerization of Gag, which in turn promotes displacement of tRNA from MA and thereby enables membrane binding.

In summary, we have shown by NMR and site-directed mutagenesis that tRNALys3 binds to the conserved basic patch on MA, the same site that interacts with PI(4,5)P2 and promotes membrane binding. Liposomes containing PI(4,5)P2, PS, and cholesterol at levels found in virions are unable to displace tRNALys3 or bind to the MA:tRNALys3 complex. Conditions that promote myristate exposure, and thereby promote membrane binding, significantly diminish the affinity of tRNALys3 for MA. Taken together, these findings support a virus assembly model in which cytoplasmic MA:tRNAs interactions prevent unassembled Gag molecules from aberrant binding to internal membranes and/or premature binding to the PM. Membrane must thus be regulated by factors beyond simply the lipid composition of the virus assembly site [50]. Likely factors that are known to promote myristate exposure include a reduction in pH that may occur in infected cells [76] or within the pH gradient of the PM [75], Gag-Gag interactions that can be induced by NC binding to clusters of NC binding sites in the RNA packaging signal [81, 82] or by combinations of NC-RNA and capsid-capsid interactions at virus assembly sites.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

MA was expressed using a vector containing both HIV-1 MA and human N-myristoyltransferase. Transfected BL21-DE3-RIL E. coli cells were grown in 2L LB broth at 37 °C until OD600 ~0.6–0.7. Cells were induced using isopropyl D-thiogalactoside (1 mM) and continued to grow for 3.5–4 hours. Following lysis by microfluidation, the supernatant was purified by polyethylenimine precipitation (0.15% w/v) and ammonium sulfate precipitation (50% saturation). The resuspended precipitate was purified using ion exchange chromatography (Q and SP columns; GE Healthcare), hydrophobicity chromatography (Butyl column; GE Healthcare), and size exclusion chromatography (Superdex 200 G75 column; GE Healthcare). Quickchange Lightening mutagenesis kits (Agilent) were used to create mutant MA constructs, which were purified as described for wild-type MA. An N-terminal histidine tag and TEV cleavage site were added to a HIV-1 MA vector lacking N-myristoyltransferase to create the myr(-)MA construct. myr(-)MA was expressed and lysed similary to MA, but was purified after PEI precipitation by gravity cobalt affinity chromatography (ThermoFisher). TEV cleavage was followed by another cobalt affinity purification step, as well as ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. Molecular weights and myristoylation efficiency were determined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry.

tRNA synthesis and purification

DNA oligonucleotides (IDT Tech) were annealed and ligated to form DNA templates containing a T7 promoter site and the tRNALys3 sequence. tRNALys3 was synthesized in vitro by T7 polymerase, and purified using sequencing gels, followed by electroelution, NaCl washes to remove residual acrylamide, and water washes to remove excess ions. After addition of MgCl2 to a concentration of 5 mM, tRNA samples were boiled for 3 minutes and snap-cooled on ice immediately before dialysis for ITC. Quality control gels (10% TB, 0.05 mM MgCl2) obtained for all samples after dialysis and immediately prior to ITC or liposome experiments confirmed that the tRNAs had not undergone degradation. In addition, all samples were incubated with MA at molar ratios between 0.25:1 and 3:1 MA:tRNA to qualitatively confirm the binding stoichiometries measured by ITC. All tRNA and protein concentrations were measured by the Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher) immediately before loading the ITC sample chamber or NMR tubes.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Protein and tRNALys3 samples were dialyzed overnight in 25 mM Tris, pH 7.0, (25 mM MES for samples at pH 5.5) 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM beta-mercaptoethanol. Dialysis buffer was filtered and used to dilute RNA and protein samples for ITC. A MicroCal itc200 (GE Healthcare) was used to analyze all samples. Protein samples were diluted to 25 μM and titrated over 20 injections with 2 μL of 400–450 μM tRNALys3 with a stirring speed of 750 rpm. Averages and standard deviations of three replicate titrations were used to calculate Kd, ΔH, ΔS, and n. All samples were compared to wild-type MA at pH 7.0 using a Student’s t-test.

1D NMR Liposome Assay

Liposomes were prepared from stock solutions of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC; Avanti), L-α-phosphatidylserine (PS; Avanti), L-α-posphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate ([PI(4,5)P2]; Avanti), and 1-stearoyl-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-myo-inositol-3′,5′-bisphosphate) ([PI(3,5)P2], L-α-phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and cholesterol; Avanti) dissolved in chloroform. Appropriate amounts of lipids were measured into tubes and dried overnight using a centrifugal vacuum. See Table S1 for lipid compositions approximating raft, non-raft, MT4 plasma membrane, and HIV-1 lipid envelope compositions. Lipids were reconstituted in buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM BME), vortexed to dissolve the lipids, and allowed to rehydrate at 37°C for at least one hour. Lipid solutions were submitted to three freeze-thaw cycles, and liposomes formed through extrusion of the solution through a 100 nm polycarbonate membrane 28 times. All liposomes were used on the day of preparation and reconstituted to a concentration of 7.6 mM lipids.

1D NMR data were obtained on a 600 MHz Bruker Avance III spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe. All data were collected at 35°C using samples containing 50 μM MA in 50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, with 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM BME, and 10% D2O. Samples with tRNA (60 μM) contained a tRNA:MA molar ratio of 1.2:1. MA samples were incubated at room temperature for at least 20 minutes and at 35°C for at least 5 minutes before collecting data in 3 mm NMR tubes. 1H-1D spectra were acquired with 512 transients, 1 sec relaxation delay, 32768 time domain points, and a spectral window of 16233 Hz.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Matrix basic patch residues are essential for tRNALys3 interactions.

tRNA outcompetes PI(4,5)P2 and raft-like membranes for binding to the matrix domain alone.

tRNA binding is inhibited by myristoyl group exposure.

The collective findings support an “entropic myristoyl switch” membrane targeting mechanism.

Acknowledgments

Support from the NIH (R01 GM42561) is gratefully acknowledged. ET and TH were supported by NIH NIGMS MARC U*STAR T34 12463 National Research Service Award grant, ET was supported by HHMI Biological Sciences Education Program grant, A.A., T.A. M.M. were supported by HHMI EXROP summer internship awards, and A.A. and T.A. were supported by HHMI EXROP Capstone program awards.

References

- 1.Jouvenet N, Bieniasz PD, Simon SM. Imaging the biogenesis of individual HIV-1 virions in live cells. Nature. 2008;454:236–40. doi: 10.1038/nature06998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jouvenet N, Simon SM, Bieniasz PD. Imaging the interaction of HIV-1 genomes and Gag during assembly of individual viral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19114–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jouvenet N, Simon SM, Bieniasz PD. Visualizing HIV-1 assembly. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:501–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jouvenet N, Zhadina M, Bieniasz PD, Simon SM. Dynamics of ESCRT protein recruitment during retroviral assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:394–401. doi: 10.1038/ncb2207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freed EO. HIV-1 assembly, release and maturation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:484–96. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Rahman SA, Nikolaitchik OA, Grunwald D, Sardo L, Burdick RC, et al. HIV-1 RNA genome dimerizes on the plasma membrane in the presence of Gag protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E201–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518572113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlson LA, Briggs JA, Glass B, Riches JD, Simon MN, Johnson MC, et al. Three-dimensional analysis of budding sites and released virus suggests a revised model for HIV-1 morphogenesis. Cell host & microbe. 2008;4:592–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita E, Sundquist WI. Retrovirus Budding. Annual Review of Cell and Develpomental Biology. 2004;20:395–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganser-Pomillos BK, Yeager M, Sundquist WI. The structural biology of HIV assembly. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:203–17. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray D, Hermida-Matsumoto L, Buser CA, Tsang J, Sigal CT, Ben-Tal N, et al. Electrostatics and the membrane association of Src: theory and experiment. Biochemistry. 1998;37:2145–59. doi: 10.1021/bi972012b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindwasser OW, Resh MD. Multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag promotes its localization to barges, raft-like membrane microdomains. J Virol. 2001;75:7913–24. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.17.7913-7924.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindwasser OW, Resh MD. Myristoylation as a target for inhibiting HIV assembly: Unsaturated fatty acids block viral budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13037–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212409999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ono A, Freed EO. Cell-Type-Dependent Tageting of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Assembly to the Plasma Membrane and the Multivesicular body. Journal of Virology. 2004;78:1552–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1552-1563.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freed EO, Orenstein JM, Buckler-White AJ, Martin MA. Single Amino Acid Changes in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Protein Block Virus Particle Production. Journal of Virology. 1994;68:5311–20. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5311-5320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ono A, Orenstein JM, Freed EO. Role of the Gag Matrix Domain in Targeting Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 assembly. Journal of Virology. 2000;74:2855–66. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2855-2866.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ebbets-Reed D, Scarlata S, Carter CA. The major homology region of the HIV-1 Gag precursor influences membrane affinity. biochemistry. 1996;35:14268–75. doi: 10.1021/bi9606399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang C, Hu J, Russell RS, Roldan A, Kleiman L, Wainberg MA. Characterization of a putative α-helix across the capsid-SP1 boundary that is critical for the multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. J Virol. 2002;76:11729–37. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11729-11737.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Accola MA, Hoglund S, Gottlinger HG. A putative a-helical structure which overlaps the Capsid-p2 boundary in the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 Gag precursor is crucial for viral particle assembly. J Virol. 1998;72:2072–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2072-2078.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono A, Demirov D, Freed EO. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus Type-1 Gag multimerization and membrane binding. J Virol. 2000;74:5142–50. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5142-5150.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platt EJ, Haffar OK. Characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55gag membrane association in a cell-free system: Requirement for a C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4594–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sandefur S, Varthakavi V, Spearman P. The I domain is required for efficient plasma membrane binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55Gag. J Virol. 1998;72:2723–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2723-2732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandefur S, Smith RM, Varthakavi V, Spearman P. Mapping and characterization of the N-terminal I domain of human immunodeficiency virus type I Pr55(Gag) J Virol. 2000;74:7238–49. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7238-7249.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dick RA, Kamynina E, Vogt VM. Effect of Multimerization on Membrane Association of Rous Sarcoma Virus and HIV-1 Matrix Domain Proteins. J Virol. 2013;87:13598–608. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01659-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang C, Loeliger E, Luncsford P, Kinde I, Beckett D, Summers MF. Entropic switch regulates myristate exposure in the HIV-1 matrix protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:517–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305665101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behnia R, Munro S. Organelle identity and the signposts for membrane traffic. Nature. 2005;438:597–604. doi: 10.1038/nature04397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono A, Ablan SD, Lockett SJ, Nagashima K, Freed EO. Phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate regulates HIV-1 Gag targeting to the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14889–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405596101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen DH, Hildreth JE. Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J Virol. 2000;74:3264–72. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3264-3272.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono A, Waheed AA, Freed EO. Depletion of cellular cholesterol inhibits membrane binding and higher-order multimerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag. Virology. 2007;360:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waheed AA, Freed EO. Lipids and membrane microdomains in HIV-1 replication. Virus research. 2009;143:162–76. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham DR, Chertova E, Hilburn JM, Arthur LO, Hildreth JE. Cholesterol depletion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus with beta-cyclodextrin inactivates and permeabilizes the virions: evidence for virion-associated lipid rafts. J Virol. 2003;77:8237–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.15.8237-8248.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ono A, Freed EO. Plasma membrane rafts play a critical role in HIV-1 assembly and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13925–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241320298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brugger B, Glass B, Haberkant P, Leibrecht I, Wieland FT, Krausslich HG. The HIV lipidome: a raft with an unusual composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2641–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan R, Uchil PD, Jin J, Shui G, Ott DE, Mothes W, et al. Retroviruses Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Murine Leukemia Virus are enriched in phosphoinositides. J Virol. 2008;82:11228–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00981-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lalonde MS, Sundquist WI. How HIV finds the door. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:18631–2. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215940109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorizate M, Sachsenheimer T, Glass B, Habermann A, Gerl MJ, Krausslich HG, et al. Comparative lipidomics analysis of HIV-1 particles and their producer cell membrane in different cell lines. Cell Microbiol. 2013;15:292–304. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell SM, Crowe SM, Mak J. Lipid rafts and HIV-1: from viral entry to assembly of progeny virions. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2001;22:217–27. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chazal N, Gerlier D. Virus Entry, Assembly, Budding, and Membrane Rafts. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews. 2003;67:226–37. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.226-237.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ono A, Freed EO. Role of lipid rafts in virus replication. Adv Virus Res. 2005;64:311–58. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(05)64010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerviel A, Thomas A, Chaloin L, Favard C, Muriaux D. Virus assembly and plasma membrane domains: which came first? Virus research. 2013;171:332–40. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Charlier L, Louet M, Chaloin L, Fuchs P, Martinez J, Muriaux D, et al. Coarse-grained simulations of the HIV-1 matrix protein anchoring: revisiting its assembly on membrane domains. Biophysical journal. 2014;106:577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercredi PY, Bucca N, Loeliger B, Gaines CR, Mehta M, Bhargava P, et al. Structural and Molecular Determinants of Membrane Binding by the HIV-1 Matrix Protein. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:1637–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kutluay SB, Zang T, Blanco-Melo D, Powell C, Jannain D, Errando M, et al. Global Changes in the RNA Binding Specificity of HIV-1 Gag Regulate Virion Genesis. Cell. 2014;159:1096–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bénas P, Bec G, Keith G, Marquet R, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, et al. The crystal structure of HIV reverse-transcription primer tRNA(Lys,3) shows a canonical anticodon loop. RNA. 2000;6:1347–55. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kleiman L, Jones C, Musier-Forsyth K. Formation of the tRNALys packaging complex in HIV-1. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:359–65. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleiman L. tRNA(Lys3): the primer tRNA for reverse transcription in HIV-1. IUBMB Life. 2002;53:107–14. doi: 10.1080/15216540211469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chukkapalli V, Hogue IB, Boyko V, Hu W-S, Ono A. Interaction between HIV-1 Gag matrix domain and phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate is essential for efficient Gag-membrane binding. J Virol. 2008;82:2405–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01614-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chukkapalli V, Inlora J, Todd GC, Ono A. Evidence in support of RNA-mediated inhibition of phosphatidylserine-dependent HIV-1 Gag membrane binding in cells. J Virol. 2013;87:7155–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00075-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chukkapalli V, Oh SJ, Ono A. Opposing mechanisms involving RNA and lipids regulate HIV-1 Gag membrane binding through the highly basic region of the matrix domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1600–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908661107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chukkapalli V, Ono A. Molecular determinants that regulate plasma membrane association of HIV-1 Gag. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:512–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson LA, Bai Y, Keane SC, Doudna JA, Hurley JH. Reconstitution of selective HIV-1 RNA packaging in vitro by membrane-bound Gag assemblies. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keane SC, Van V, Frank HM, Sciandra CA, McCowin S, Santos J, et al. NMR detection of intermolecular interaction sites in the dimeric 5′-leader of the HIV-1 genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:13033–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614785113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Helmling C, Keyhani S, Sochor F, Furtig B, Hengesbach M, Schwalbe H. Rapid NMR screening of RNA secondary structure and binding. Journal of biomolecular NMR. 2015;63:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s10858-015-9967-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Puglisi EV, Puglisi JD. Probing the conformation of human tRNA(3)(Lys) in solution by NMR. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorenz C, Lunse CE, Morl M. tRNA Modifications: Impact on Structure and Thermal Adaptation. Biomolecules. 2017;7 doi: 10.3390/biom7020035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tran T, Liu Y, Marchant J, Monti S, Seu M, Zaki J, et al. Conserved determinants of lentiviral genome dimerization. Retrovirology. 2015;12:83. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freed EO, Englund G, Martin AM. Role of the Basic Domain of Human Immondeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix in Macrophage Infection. Journal of Virology. 1995;69:3949–54. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3949-3954.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bouamr F, Scarlata S, Carter CA. Role of myristylation in HIV-1 Gag assembly. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6408–17. doi: 10.1021/bi020692z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hermida-Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease triggers a myristoyl switch that modulates membrane binding fo Pr55gag and p17MA. J Virol. 1999;73:1902–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.1902-1908.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fledderman EL, Fujii K, Ghanam RH, Waki K, Prevelige PE, Freed EO, et al. Myristate exposure in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein is modulated by pH. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9551–62. doi: 10.1021/bi101245j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saad JS, Loeliger E, Luncsford P, Liriano M, Tai J, Kim A, et al. Point mutations in the HIV-1 matrix protein turn off the myristyl switch. J Mol Biol. 2007;366:574–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paillart J-C, Gottlinger HG. Opposing effects of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix mutations support a myristyl switch model of Gag membrane targeting. J Virol. 1999;73:2604–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2604-2612.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marquardt D, Geier B, Pabst G. Asymmetric lipid membranes: towards more realistic model systems. Membranes. 2015;5:180–96. doi: 10.3390/membranes5020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2008;9:112–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCartney AJ, Zhang Y, Weisman LS. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate: low abundance, high significance. BioEssays. 2014;36:52–64. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stapulionis R, Deutscher MP. A channeled tRNA cycle during mammalian protein synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7158–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McLaughlin S, Murray D. Plasma membrane phosphoinositide organization by protein electrostatics. Nature. 2005;438:605–11. doi: 10.1038/nature04398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aloia RC, Tian H, Jensen FC. Lipid composition and fluidity of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope and host cell plasma membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5181–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devaux PF, Morris R. Transmembrane asymmetry and lateral domains in biological membranes. Traffic. 2004;5:241–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Todd GC, Duchon A, Inlora J, Olson ED, Musier-Forsyth K, Ono A. Inhibition of HIV-1 Gag-membrane interactions by specific RNAs. RNA. 2017;23:395–405. doi: 10.1261/rna.058453.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Summers MF, Henderson LE, Chance MR, Bess JWJ, South TL, Blake PR, et al. Nucleocapsid zinc fingers detected in retroviruses: EXAFS studies of intact viruses and the solution-state structure of the nucleocapsid protein from HIV-1. Protein Science. 1992;1:563–74. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Puglisi EV, Puglisi JD. Secondary structure of the HIV reverse transcription initiation complex by NMR. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:863–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alfadhli A, Still A, Barklis E. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix binding to membranes and nucleic acids. J Virol. 2009;83:12196–203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01197-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alfadhli A, McNett H, Tsagli S, Bächinger HP, Peyton DH, Barklis E. HIV-1 matrix protein binding to RNA. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:653–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Saad JS, Ablan SD, Ghanam RH, Kim A, Andrews K, Nagashima K, et al. Structure of the myristylated human immunodeficiency virus type 2 matrix protein and the role of phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate in membrane targeting. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:434–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:50–61. doi: 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Makutonina A, Voss TG, Plymale DR, Fermin CD, Norris CH, Vigh S, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of T-lymphoblastoid cells reduces intracellular pH. Journal of virology. 1996;70:7049–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7049-7055.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feng Y-X, Li T, Campbell S, Rein A. Reversible binding of recombinant Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 Gag protein to nucleic acids in virus-like particle assembly in vitro. J Virol. 2002;76:11757–62. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11757-11762.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Campbell S, Vogt VM. Self-assembly in vitro of of purifyed CA-NC proteins from Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1995;69:6487–97. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6487-6497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Muriaux D, Mirro J, Harvin D, Rein A. RNA is a structural element in retrovirus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5246–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yu F, Joshi SM, Ma YM, Kingston RL, Simon MN, Vogt VM. Characterization of Rous sarcoma virus Gag particles assembled in vitro. J Virol. 2001;75:2753–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2753-2764.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lu K, Heng X, Garyu L, Monti S, Garcia E, Kharytonchyk S, et al. NMR detection of structures in the HIV-1 5´-leader RNA that regulate genome packaging. Science. 2011;344:242–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1210460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Keane SC, Heng X, Lu K, Kharytonchyk S, Ramakrishnan V, Carter G, et al. Structure of the HIV-1 RNA packaging signal. Science. 2015;348:917–21. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa9266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saad JS, Miller J, Tai J, Kim A, Ghanam RH, Summers MF. Structural basis for targeting HIV-1 Gag proteins to the plasma membrane for virus assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602818103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.