Abstract

Significant advances have been made recent years elucidating antiviral immune mechanisms that protect the host from viral infection. Similarly, our understanding of how viruses bind, enter, and replicate within host cells has continued to grow. Yet, viruses continue to take a toll on human health. The influence of chemicals in the environment is among key factors that influence outcomes of viral infection. There is a growing appreciation of the effects that exogenous environmental chemical exposures have on the immune system and antiviral immunity. Epidemiological studies have linked a variety of chemical exposures to poorer health, increased incidence of infection, and worsened vaccine responses. However, the mechanisms that govern these associations are not well understood, limiting our ability to predict or mitigate the effects of environmental exposures on public health. This brief review focuses on recent advances in the field, highlighting novel in vitro and in vivo findings informed by past foundational studies. Furthermore, current information suggests avenues of investigation that have yet to be explored, but which will significantly impact on our understanding about how environmental exposures impact viral defenses, vaccine efficacy, and the spread of contemporary and emerging viral pathogens.

1. Introduction

There are over 1400 known human pathogens, of which 219 are classified as viral agents of disease [1,2]. In spite of continuous improvements in public health and medicine, infectious diseases continue to cause substantial morbidity, mortality, and socioeconomic loss. Viruses regularly instigate localized epidemics, and can give rise to pandemics. Viruses constitute a particular global health concern due to the limited range of therapeutic agents, the ability of many viruses to reassort and mutate, and their multiple transmission routes. Notably, influenza viruses and respiratory syncytial virus are among major causes of virally mediated respiratory illness [3], while hepatitis viruses are transmitted via oral-fecal exchange and blood [4]. In addition to these common viral diseases, there is increasing awareness of emerging viral diseases, such as those triggered by outbreaks of Zika and Ebola viruses. As such, the World Health Organization and many national public health programs maintain substantial focus on the continue threat of viral epidemic and pandemic diseases.

The past several decades have heralded major advances in our understanding of immune responses to viral infection. Yet, differences in vulnerability to viral infection remain. For instance, it is still a mystery why, during outbreaks of the same viral subtype, illness ranges from asymptomatic to severe within immunocompetent populations. Some variances are explained by age, sex, and genetics; however, these are not adequate to account for all disparities. The host’s environment is one extrinsic factor rarely taken into account. In general, “environment” encompasses characteristics of where one lives and works, diet, chemicals, and natural products to which one comes into contact. We are constantly exposed to a broad assortment of substances from our environment, skew regulatory and inflammatory pathways, and predispose the host to exacerbated pathology subsequent to viral infection (Figure 1).

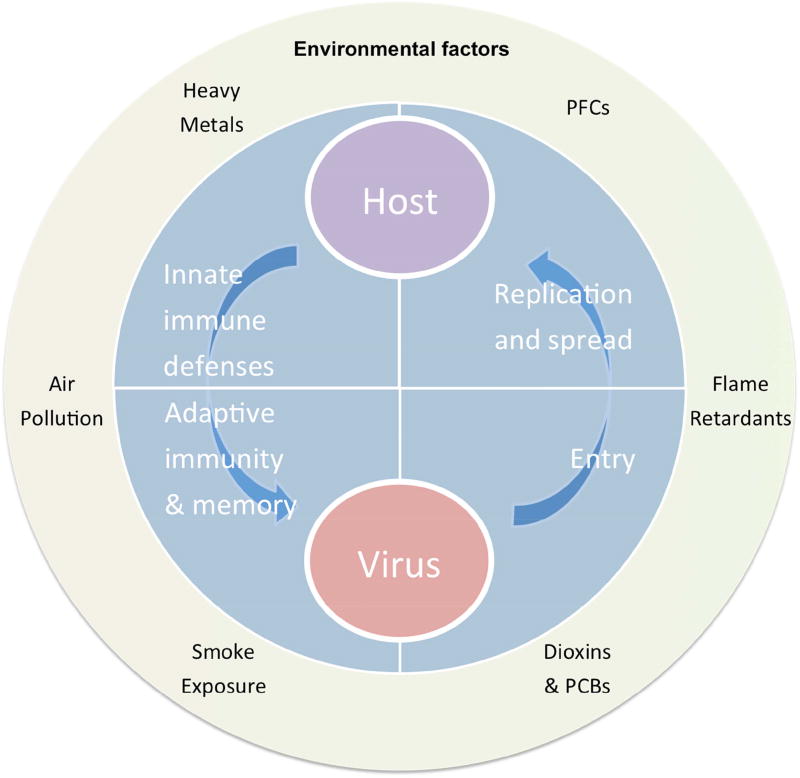

Figure 1.

Host-Virus interactions consist of a balance between host immune defenses and viral immune evasion mechanisms. Emerging evidence shows that environmental factors play a major role in shaping host responses to viral infection, and may also shape how viruses bind, replicate, and spread during the course of infection.

This is not theoretical. Emerging evidence points to environmental exposure as important, often unnoticed, contributors to individual and population level differences in antiviral responses [5]. Yet, the mechanisms by which environmental factors affect antiviral defenses remain poorly defined. Delineating cause-and-effect relationships between specific environmental factors and viral diseases will reveal new opportunities to intervene and prevent disease. With these ideas in mind, this commentary has two goals: 1) highlight recent advances in knowledge of ways in which environmental exposures influence antiviral defenses; and 2) frame key opportunities for future study.

2. Antiviral defense mechanisms

The immune system consists of an integrated cellular network that protects the host from infection, and eliminates viruses and virus-infected cells during infection [6]. Initially, protection is conferred in a general way, via innate immunity. Innate immune responses are usually rapid, unspecific, and not long lasting. For example, viral infection triggers host cells to produce interferons (IFNs), which restrict viral replication by influencing events in host cells, and activating leukocyte defense mechanisms [7,8]. Deregulation of the innate immune system allows viruses to replicate unfettered, endangering the host, and contributing to the continued spread of the virus. Viruses have evolved mechanisms to thwart the innate immune system. Examples include inhibition of type I interferon (IFN-I) [9], and decoy molecules that assist in evading intracellular detection by cells of the innate immune system [10].

In addition to viral control, signals from the innate immune system stimulate the adaptive immune system. Adaptive responses to viral infection rely on the activation, expansion, and differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes. Virus-specific cytotoxic T cells (CTL) are mainly responsible for complete viral clearance during primary infection, while a combination of CTL, helper T cells, and virus-specific antibodies contribute to host protection during recurrent infections. Consequently, improper or insufficient adaptive immune responses can affect outcomes from both initial and repeated infections.

Establishing immunological memory is the underpinning of vaccination, the most effective means of combating viral disease. The efficacy of most vaccines is mediated by sustained production of highly specific antibodies to conserved viral antigens. Current vaccination efforts have led to an unparalleled reduction in outbreaks of rubella, measles, polio, and mumps, and the global eradication of small pox [11]. Some viruses, such as influenza viruses, are highly mutable and require annual vaccination in order to maintain protection. For other viruses, such as Dengue virus, Zika virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), vaccines to prevent their spread are actively being developed [12].

Along with the interactive network of innate and adaptive immune defenses that protect from primary and repeated infection, viral pathogenesis is influenced by the ability of a virus to gain entry into host cells in order to replicate. While the immune system has mechanisms to interfere with these steps, viral genomes continue to evolve strategies that evade detection or elimination. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) [13,14], HIV-1 [15,16], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) early gene products [17], and non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of influenza A virus (IAV) [18] override host cell signaling, promote viral protein synthesis, genome integration, replication, and restrict release of innate effector cytokines capable of alerting nearby cells and inducing an antiviral state.

3. Environmental deregulation of antiviral defenses

Given the complex defense mechanisms to fight viral infections, there are many aspects that, if disturbed, could contribute to more severe clinical outcomes. However, of the 219 identified viral pathogens, only a handful have been studied within the context of defining how environmental exposures influence this integrated network of defense mechanisms. The scope of research to evaluate how environmental chemicals impinge on antiviral defenses, viral latency, or influence viral infection and replication machinery is equally lean considering the independent depth of knowledge in the fields of virology and toxicology.

Despite the limited focus, when examined, the evidence overwhelmingly supports that pollutant exposure influences viral pathogenesis (Figure 1) [19,20]. Research that implicates a role for environmentally derived chemicals include epidemiology studies, animal models, and cultured cell lines. Environmental contaminants studied include heavy metals, dioxins/polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), perfluorinated chemicals (PFCs), diesel exhaust, and biomass smoke. For some contaminants (e.g., dioxin-like compounds (DLCs) and air pollutants) there are data from multiple experimental systems, whereas for other agents, such as PFCs, the research and model systems are more limited. In the following sections, we highlight several examples of ways in which specific environmental contaminants influence anti-viral defenses.

3.1 Exposure to environmental chemicals affects viral replication

The impact of environmental agents on the ability of viruses to enter host cells has received scant attention. However, several studies provide evidence that exposure to environmental contaminants affects viral replication machinery within infected cells. For example, Coxsackievirus B3 replicates to higher viral titers in livers of mice exposed to flame retardant BDE-99 in a dose-dependent manner [21]. In other studies, in vitro treatment with DLCs enhances HIV-1, CMV, and EBV replication in several different cell types [22–24]. A limitation of these studies with DLCs is that they were performed exclusively using cell lines. That DLCs influence viral replication is bolstered by epidemiological studies, which show an association between increased DLC exposure and increased incidence of lower respiratory infections, although the effect on viral titers is unknown [25, 26]. During primary IAV infection, exposure to the prototype DLC, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) increases viral titers in lungs in rats, but not mice [27,28]. Thus, it remains uncertain how in vivo exposure to environmentally relevant DLC doses affects viral replication within an infected host organism, whether non-human or human. Nonetheless, these studies collectively support the idea that environmental contaminants influence viral replication within infected cells.

3.2 Environmental exposures influence antiviral interferon production

Interferons (IFN) are a family of cytokines that are released by immune and non-immune cells in response to infection. They promote antiviral innate immune responses within infected and uninfected cells, alert distal leukocytes to infection, and refine adaptive immune mechanisms. Type I interferons (IFN-I) are produced by infected cells, and by certain immune cells. Unchecked IFN-I production leads to severe consequences for the host; therefore, IFN-I is tightly regulated by IRF7 [29]. Deemed a master regulator, IRF7 is a prime target for viral inactivation or degradation [30]. Several recent reports suggest signaling pathways upstream of IFN-I production are sensitive to environmental exposures; specifically, to ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). In fibroblasts, AHR signaling constrains in vitro IFN-I production [31]; however, this may be cell type specific [32]. While it remains to be conclusively determined whether IFN-I gene expression is directly regulated by AHR. The aryl hydrocarbon interacting protein (AIP) dissociates from the AHR upon activation, and can block IRF7 function and thus, IFN-I production [33]. AIP also interacts with several viral effectors [35], making it plausible for viruses to hijack this pathway and suppress IFN-I responses. This “double hit” scenario allows the virus to delay or escape immune detection.

In addition to affecting regulation of IFN-I, AHR signaling also modulates IFNγlevels. In a mouse model of ocular herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection, AHR activation by TCDD dampened IFNγproduction by T cells, leading to an improved disease outcome [34]. However, during IAV infection, AHR activation disrupts regulation of IFNγin a cell-type specific manner, with the net result being a negative effect on host resistance. Specifically, AHR signaling increases IFNγproduction by myeloid cells, while decreasing T cell IFNγproduction [35,36]. Precisely how AHR signaling affects IFNs in the context of other viruses remains to be understood. Thus, using a combination of in vivo and ex vivo systems to better define the influence of environmental agents on innate antiviral defenses is a fertile area for future investigation.

4. Detrimental effects of environmental exposures on chemotactic mediators

Another important feature of leukocytes is their ability sense infection or injury and rapidly migrate towards specific areas to control pathogen replication. This process is coordinated by a network of soluble and cell surface mediators, which influence leukocyte attachment, rolling, and directional migration with minimal tissue damage. Recently, Meldrum and colleagues presented evidence that diesel exhaust particulates (DEPs), a contributor of adverse health effects in urban and high traffic areas, attenuate the expression of soluble chemoattractants. In this study, DEPs on lung production of the chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 (CXCL10), which influences immune cell recruitment to injured or infected tissues. In human macrophages, diesel extracts inhibited CXCL10, CXCL11, and chemokine (C-C motif) 17 (CCL17) [37]. These alterations to the chemokine milieu were observed in both resting cells and cells stimulated with toll like receptor (TLR) ligands, evidence that DEP exposure can significantly impact cellular migration. What effect these altered chemokine levels have on antiviral defenses in vivo is unknown. Future research that more thoroughly evaluates the impact of chemical exposures on chemokine production in vivo, and connects changes in chemokine levels to outcomes following viral infection will advance understanding of how environmental exposures modify leukocyte migration.

5. Effects on adaptive antiviral immune responses

Lymphocytes are at the core of the adaptive immune system. Humoral responses involve CD4+ T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and antibodies, whereas cell-mediated antiviral immune responses are predominantly driven by CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Several environmental contaminants have been shown to affect adaptive immune responses to viral infections. Moreover, in contrast to innate antiviral defenses, these studies were conducted using animal models and human populations with defined exposures.

There have been several reported associations of a particular environmental exposure with reduced vaccine induced antibody responses. Notably, in 2006, Heilmann et al. showed that early postnatal PCB exposure was a very strong predicator of decreased antibody responses to tetanus and Diphtheria toxoid vaccines in young children [38]. Other studies link maternal TCDD and PCB exposure to reduced vaccination responses, as well as increased incidence of upper respiratory infections [39,40]. Increasing PCB concentrations in infants have also been associated with lower antibody responses to the Mycobacterium bovis bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine at 6 months of age, significant because this is the main defense against pediatric tuberculosis [41]. Furthermore, when PCB and DDE (dichlorodiphenyl-dichloroethylene; the primary metabolite of the pesticide DDT) levels were analyzed concurrently, PCB–DDE additivity was observed. This suggests that chemical mixtures may be more detrimental than a single chemical exposure, yet few studies consider mixture effects.

Perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) are ubiquitous in the environment, have a long half-life, and are readily detected throughout the population. Several studies have examined the relationship between PFC concentrations and antibody levels, although findings are mixed[42]. Some studies provide compelling evidence that exposure to PFCs is inversely associated with vaccine titers, while other studies show no correlation [43–45]. PFCs contain two broad classes of chemicals, perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). These discrepancies may reflect that some studies specify a particular compound, while others examine a class or sub-class of PFCs. Nonetheless, because these compounds are universal and persistent, additional research to better define their overall immunotoxicity will inform vaccineinducible immunity in general, and antiviral immunity specifically.

In addition to persistent organic pollutants, several studies have examined associations between metals and vaccination. Xu et al. reported that children exposed to lead show a decreased response to the hepatitis B vaccine [46]. In this study, nearly 50% of children developed subpar and unprotective antibody levels. Separately, Lin et al. analyzed vaccine-specific antibody titers in children exposed to metals and metalloids [46]. Unique in its broad focus, they investigated antibody titers against seven common bacterial and viral pathogens: Diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, hepatitis B virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, polio virus, and measles virus. No initial changes were found, but antibody levels waned significantly as the lead exposed children aged, in stark contrast to the reference population. These studies provide evidence that heavy metal exposures stymie the adaptive immune system, preventing generation or maintenance of immunological memory over time, lessening the effectiveness of vaccination.

While these reports illustrate that environmental exposures likely contribute to poorer responses to vaccines, they do not reveal mechanisms via which different environmental chemicals cause these changes, nor do they provide specific details as to how particular environmental chemicals affect cell-mediated or humoral responses to viral infections. Recent studies focused on DLCs have shown that during acute primary infection with IAV, TCDD severely suppresses the proliferation and differentiation of virus-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes and dampens IAV-specific IgG levels [32,47]. Also, virus-specific CD8+ memory T cells exhibit a delayed response upon re-infection [48]. This is due, at least in part, to AHR-mediated changes in dendritic cells. AHR activation by TCDD reduces the trafficking of DCs from the infected lung to lymph nodes, and dampens the ability of DCs to activate naïve IAV-specific CD8+T cells [48,49]. Less well understood are how other AHR-binding chemicals affect antiviral immune defenses. Likewise, although immunomodulatory, the precise mechanisms via which PFCs and heavy metals exert immunotoxicity remain less clear. The cellular and molecular mechanisms by which other environmental agents alter immune responses to viral infection are less well understood, but are fertile areas for future research. Indeed, for many chemicals substances there is little to no data regarding effects on adaptive defenses in general, or antiviral defenses specifically.

6. Concluding remarks

Major progress has been made in reducing the global burden of infectious diseases, including those caused by viruses. Advances in basic virology and immunology continue to expand our appreciation of the astonishing intricacy of immune responses to viral pathogens, and the variety of ways viruses circumvent these protective responses. We have also come to realize that in spite of tremendous forward progress, viruses remain a continuing health threat, and we have much to learn about how environment exposures impinge on critical antiviral innate and adaptive immune responses.

In addition to identifying risk factors within populations, mechanistic understanding how environmental agents modify the antiviral processes are imperative, as it will lead to novel discoveries about aspects of viral replication and host defenses that are susceptible to modulation by exogenous chemicals. Revelation of molecular targets of environmental chemicals will also uncover new targets for novel therapeutic strategies to modulate antiviral immune defenses. Consequently, current challenges are to expand research in this area to more viruses and more environmental exposures, and to integrate in vivo, in vitro, in silico, and epidemiological approaches to define how particular exogenous chemicals affect anti-viral immunity. Then the complicated issue of mixed exposures can be addressed. Confronting exposure to combinations of exogenous factors is necessary if we are to make transformative improvements to approaches for the treatment and prevention of viral disease. Effectively contending with these issues to improve public health will result from increased collaboration between the fields of immunology, toxicology, and virology.

Acknowledgments

The authors are supported by grants from the United States National Institutes of Health (R01-ES0004862, R01-ES023260, T32-ES07026, and P30-ES01247).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

disclosures: The authors declare that they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Woolhouse Mea. Human viruses: discovery and emergence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017. 2012;367(1604):2864–2871. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de las Heras A, Islas-Espinoza M, Chávez AA. Pollution: The Pathogenic and Xenobiotic Exposome of Humans and the Need for Technological Change. health. 2016;4:5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferkol T, Schraufnagel D. The Global Burden of Respiratory Disease. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2014;11:404–406. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201311-405PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. Global hepatitis report. 2017;2017:83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feingold BJ, Vegosen L, Davis M, Leibler J, Peterson A, Silbergeld EK. A niche for infectious disease in environmental health: rethinking the toxicological paradigm. Environmental health perspectives. 2010;118:1165. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nature immunology. 2006;7:131. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kato H, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Yoneyama M, Yamamoto M, Matsui K, Uematsu S, Jung A, Kawai T, Ishii KJ. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O'garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2015;15:87–103. doi: 10.1038/nri3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felix J, Savvides SN. Mechanisms of immunomodulation by mammalian and viral decoy receptors: insights from structures. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2017;17:112–129. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plotkin SA, Plotkin SA. Correlates of vaccine-induced immunity. Clinical infectious diseases. 2008;47:401–409. doi: 10.1086/589862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haynes BF. New approaches to HIV vaccine development. Current opinion in immunology. 2015;35:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen MH, Paludan SR. Viral evasion of DNA-stimulated innate immune responses. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2017;14:4–13. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2016.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brinkmann MM, Dağ F, Hengel H, Messerle M, Kalinke U, Čičin-Šain L. Cytomegalovirus immune evasion of myeloid lineage cells. Medical microbiology and immunology. 2015;204:367–382. doi: 10.1007/s00430-015-0403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins DR, Collins KL. HIV-1 accessory proteins adapt cellular adaptors to facilitate immune evasion. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1003851. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Sage V, Mouland AJ, Valiente-Echeverria F. Roles of HIV-1 capsid in viral replication and immune evasion. Virus research. 2014;193:116–129. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott RS. Epstein–Barr virus: a master epigenetic manipulator. Current Opinion in Virology. 2017;26:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hale BG, Randall RE, Ortín J, Jackson D. The multifunctional NS1 protein of influenza A viruses. Journal of General Virology. 2008;89:2359–2376. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/004606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heilmann C. Environmental Toxicants and Susceptibility to Infection. In: Dietert RR, editor. Immunotoxicity, Immune Dysfunction, and Chronic Disease. Luebke RW: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connellan SJ. Lung diseases associated with hydrocarbon exposure. Respiratory Medicine. 2017;126:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundgren M, Darnerud PO, Ilbäck N-G. The flame-retardant BDE-99 dose-dependently affects viral replication in CVB3-infected mice. Chemosphere. 2013;91:1434–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murayama T, Inoue M, Nomura T, Mori S, Eizuru Y. 2, 3, 7, 8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin is a possible activator of human cytomegalovirus replication in a human fibroblast cell line. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;296:651–656. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00921-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kashuba EV, Gradin K, Isaguliants M, Szekely L, Poellinger L, Klein G, Kazlauskas A. Regulation of transactivation function of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded EBNA-3 protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:1215–1223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509036200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue H, Mishima K, Yamamoto-Yoshida S, Ushikoshi-Nakayama R, Nakagawa Y, Yamamoto K, Ryo K, Ide F, Saito I. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated induction of EBV reactivation as a risk factor for Sjögren’s syndrome. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188:4654–4662. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dallaire F, Dewailly É, Vézina C, Muckle G, Weber J-P, Bruneau S, Ayotte P. Effect of prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls on incidence of acute respiratory infections in preschool Inuit children. Environmental health perspectives. 2006;114:1301. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stølevik SB, Nygaard UC, Namork E, Haugen M, Kvalem HE, Meltzer HM, Alexander J, van Delft JH, van Loveren H, Løvik M. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins is associated with increased risk of wheeze and infections in infants. Food and chemical toxicology. 2011;49:1843–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang YG, Lebrec H, Burleson GR. Effect of 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on pulmonary influenza virus titer and natural killer (NK) activity in rats. Toxicological Sciences. 1994;23:125–131. doi: 10.1006/faat.1994.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burleson GR, Lebrec H, Yang YG, Ibanes JD, Pennington KN, Birnbaum LS. Effect of 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) on Influenza Virus Host Resistance in Mice. Fundamental and Applied Toxicology. 1996;29:40–47. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Honda K, Yanai H, Negishi H, Asagiri M, Sato M, Mizutani T, Shimada N, Ohba Y, Takaoka A, Yoshida N. IRF-7 is the master regulator of type-I interferon-dependent immune responses. Nature. 2005;434:772–777. doi: 10.1038/nature03464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.García-Sastre A. Ten strategies of interferon evasion by viruses. Cell host & microbe. 2017;22:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada T, Horimoto H, Kameyama T, Hayakawa S, Yamato H, Dazai M, Takada A, Kida H, Bott D, Zhou AC. Constitutive aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling constrains type I interferon-mediated antiviral innate defense. Nature immunology. 2016;17:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni.3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neff-LaFord HD, Vorderstrasse BA, Lawrence BP. Fewer CTL, not enhanced NK cells, are sufficient for viral clearance from the lungs of immunocompromised mice. Cellular immunology. 2003;226:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou Q, Lavorgna A, Bowman M, Hiscott J, Harhaj EW. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacting protein targets IRF7 to suppress antiviral signaling and the induction of type I interferon. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290:14729–14739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.633065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veiga-Parga T, Suryawanshi A, Rouse BT. Controlling viral immuno-inflammatory lesions by modulating aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling. PLoS pathogens. 2011;7:e1002427. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neff-LaFord H, Teske S, Bushnell TP, Lawrence BP. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation during influenza virus infection unveils a novel pathway of IFN-γ production by phagocytic cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;179:247–255. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell KA, Lawrence BP. T cell receptor transgenic mice provide novel insights into understanding cellular targets of TCDD: suppression of antibody production, but not the response of CD8+ T cells, during infection with influenza virus. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2003;192:275–286. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaguin M, Fardel O, Lecureur V. Exposure to diesel exhaust particle extracts (DEPe) impairs some polarization markers and functions of human macrophages through activation of AhR and Nrf2. PloS one. 2015;10:e0116560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heilmann C, Grandjean P, Weihe P, Nielsen F, Budtz-Jøorgensen E. Reduced antibody responses to vaccinations in children exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. PLoS medicine. 2006;3:e311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stølevik SB, Nygaard UC, Namork E, Haugen M, Meltzer HM, Alexander J, Knutsen HK, Aaberge I, Vainio K, van Loveren H. Prenatal exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and dioxins from the maternal diet may be associated with immunosuppressive effects that persist into early childhood. Food and chemical toxicology. 2013;51:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hochstenbach K, Van Leeuwen D, Gmuender H, Gottschalk R, Støolevik SB, Nygaard UC, Løovik M, Granum B, Namork E, Meltzer HM. Toxicogenomic profiles in relation to maternal immunotoxic exposure and immune functionality in newborns. Toxicological Sciences. 2012;129:315–324. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jusko TA, De Roos AJ, Lee SY, Thevenet-Morrison K, Schwartz SM, Verner M-A, Murinova LP, Drobná B, Kočan A, Fabišiková A. A birth cohort study of maternal and infant serum PCB-153 and DDE concentrations and responses to infant tuberculosis vaccination. Environmental health perspectives. 2016;124:813. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang ET, Adami H-O, Boffetta P, Wedner HJ, Mandel JS. A critical review of perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctanesulfonate exposure and immunological health conditions in humans. Critical reviews in toxicology. 2016;46:279–331. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2015.1122573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein CR, McGovern KJ, Pajak AM, Maglione PJ, Wolff MS. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and indicators of immune function in children aged 12–19 y: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Pediatric research. 2016;79:348. doi: 10.1038/pr.2015.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kielsen K, Shamim Z, Ryder LP, Nielsen F, Grandjean P, Budtz-Jøorgensen E, Heilmann C. Antibody response to booster vaccination with tetanus and diphtheria in adults exposed to perfluorinated alkylates. Journal of immunotoxicology. 2016;13:270–273. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2015.1067259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grandjean P, Barouki R, Bellinger DC, Casteleyn L, Chadwick LH, Cordier S, Etzel RA, Gray KA, Ha E-H, Junien C. Life-long implications of developmental exposure to environmental stressors: new perspectives. Endocrinology. 2016;2016:10–16. doi: 10.1210/EN.2015-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin X, Xu X, Zeng X, Xu L, Zeng Z, Huo X. Decreased vaccine antibody titers following exposure to multiple metals and metalloids in e-waste-exposed preschool children. Environmental Pollution. 2017;220:354–363. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawrence BP, Roberts AD, Neumiller JJ, Cundiff JA, Woodland DL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation impairs the priming but not the recall of influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cells in the lung. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;177:5819–5828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jin GB, Winans B, Martin KC, Lawrence BP. New insights into the role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the function of CD11c+ cells during respiratory viral infection. European journal of immunology. 2014;44:1685–1698. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin G-B, Moore AJ, Head JL, Neumiller JJ, Lawrence BP. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation reduces dendritic cell function during influenza virus infection. Toxicological sciences. 2010;116:514–522. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]