Abstract

Middle school students with emotional and behavioral disorders are at risk for myriad negative outcomes. Transitioning between schools may increase risk for students being reintegrated into their neighborhood school. The current study seeks to inform supports for students and their families during these transitions. Students With Involved Families and Teachers (SWIFT) is an initiative being conducted in a small urban area in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Parent, student, and school-based supports were provided across a yearlong transition for students receiving special education services in a behavioral day-treatment program. A case example is used to describe the essential features of SWIFT, illustrate the experience of a student and his family, and outline lessons learned for successful home-school collaboration.

Students with emotional and behavioral disorders (EBD) often struggle in school and addressing their needs can exert considerable strain on school districts and social services. For example, students with EBD tend to earn lower scores on achievement tests than their typical peers and peers with other disabilities, a negative trend that widens as students age (Wagner et al., 2006). In addition, students with EBD often have lower rates of participation in classroom activities, and teachers can have lower behavioral and academic expectations for these students (Bradley, Doolittle, & Bartolotta, 2008).

Many students with EBD are removed from mainstream educational settings and placed in treatment settings, such as self-contained classrooms, day-treatment schools, or residential placements (U.S. Department of Education, 2005). Further, data show that when reintegrating students with EBD into less restrictive environments (e.g., their neighborhood school), the intensive services provided in more restrictive settings are not sustainable and the intensity of support abruptly decreases (Wagner et al., 2006). As a result, students with EBD who experience success in highly structured, well supervised, and encouraging settings can be at risk when they transition to schools without similar systems in place (Wagner et al., 2006). Targeted support for students with EBD is necessary to promote their successful transition to less restrictive environments. Coordinated interventions targeting emotional and behavioral skills and family involvement have the potential to maintain students in least restrictive settings and increase high school graduation rates.

The SWIFT Intervention

Students With Involved Families and Teachers (SWIFT) is grounded in social learning theory, a theory suggesting that children and adolescents learn from their social environments. According to social learning theory, students who demonstrate behavior problems often have significant skill deficits and their problem behaviors may inadvertently be reinforced such that they lack a sufficient range of alternative behavioral responses to use even if they are motivated to do so (Chamberlain, 2003).

SWIFT staff actively collaborate with the parent(s), student, and school team members (teachers, school psychologists, administrators, etc.) on goal setting and intervention designed to ensure a good contextual fit for all settings. We have found that such collaboration promotes consistency of supports across settings and increases adherence to the intervention plan. In addition, prior studies have shown that parents must be engaged as a part of the student's intervention team to make sure that positive changes last (e.g., Fantuzzo, McWayne, Perry, & Childs, 2004; Minke & Anderson, 2005). SWIFT includes four integrated components adapted from Multidisciplinary Treatment Foster Care (MTFC; Chamberlain, 2003): (a) weekly behavioral progress monitoring data from parents and teachers, (b) program supervision to facilitate communication and coordination, (c) parent coaching, and (d) skills coaching for the student.

Behavioral Progress Monitoring

The Parent Daily Report (PDR) and the Teacher Daily Report (TDR) are used for behavioral progress monitoring. The PDR includes 37 problem and 17 prosocial items and the TDR includes 42 problem and 21 prosocial items. An assessor calls the parent or teacher once a week and asks whether the student engaged in any of the prosocial behaviors on the list or any of the problem behaviors and, if so, if it was stressful. This call takes approximately 3–5 min. Parents and teachers also have the option of entering the data directly into a secure web-based database. The PDR and TDR data are graphed over time and used to identify problem behaviors to target in weekly interventions, to identify the prosocial behaviors students exhibit, and to monitor progress over time throughout the intervention.

Program Supervision

The program supervisor (PS) is the primary contact between the SWIFT team and the school teams. Contact from the PS includes providing updates about relevant family information, problem solving the myriad problems that arise during the transition, and helping translate the supports provided at the day-treatment school to the neighborhood school. The PS is also responsible for coordinating and supervising the student skills and the parent coaches. During a weekly clinical supervision meeting, the PS provides the team with an update on the student's progress and support needs from the perspective of the school team. Then the PS reviews weekly PDR and TDR data to identify behaviors to target in weekly sessions and to evaluate whether such interventions were successful. Next, the student skills and parent coaches give an update about the skills addressed with the parent and the student. Planning for the content of the next week's sessions incorporates the PDR and TDR data; the needs and/or barriers faced by the student, family, and school; and the skills and strengths of the student, family, and school.

Parent coach (PC)

The PC focuses on supporting the parents in their communications with the school and on coordinating routines at home. SWIFT PCs help parents practice communicating with the school team, prepare parents for school meetings, and help parents set up charts and other encouragement systems at home. The PC meets with the family once a week at home, at the school, or at a location requested by the parent. The PC is also available for support between meetings by phone, email, text, or in person as needed.

Skills coach (SC)

The SC is typically a young adult (i.e., graduate student) who coaches and models appropriate behavior at school and in the community. SCs focus on helping the student develop prosocial skills and reinforce the use of these positive skills with the student's peers and adults. The SC meets with the student once a week at school or in the community.

Case Example

Tyler, a 12-year-old Caucasian male, entered the SWIFT program in the spring of sixth grade. He lived with his parents and sister in an urban county in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Tyler was receiving special education services for emotional disturbance and a learning disability at a local behavioral day-treatment school. He was identified for SWIFT because he had successfully progressed through the school's level system and had reliably self-monitored his behavior. These criteria triggered the transition back to his neighborhood school. Each week Tyler met one-on-one with the SC. On average, these sessions lasted 45 min. Parent sessions were conducted weekly with his mother for 1 hr. In addition to the SWIFT team, Tyler's transition support team included Tyler's day-treatment school transition classroom teacher, classroom teachers at both schools, and the school psychologist at the neighborhood school. The SWIFT intervention occurred in three phases: (a) engagement, (b) skill development and practice, and (c) maintenance.

Phase 1: Engagement

Engagement is the first phase of the SWIFT program and includes rapport building, goal identification, and exploring methods to assist the family during the transition. This information is used to inform interventions in Phase 2. The engagement phase lasts for approximately four weeks.

Program supervision

Prior to the PC and SC sessions, the PS met with Tyler's mother to introduce the SWIFT program and to orient her to the staff roles and the supports available to the family and school. During Phase 1 the PS met with Tyler's day-treatment school transition classroom teacher and the school psychologist at the neighborhood school to introduce the SWIFT program and to gather information from their perspectives on Tyler's strengths as well as his skill and support needs for the upcoming transition. They identified that Tyler was highly motivated to return to his neighborhood school and would benefit from skills that would allow him to follow directions without arguing, to be patient with the transition process, and to complete homework consistently. During the clinical supervision meetings, the SWIFT team identified initial intervention targets based on information gathered across settings. After the clinical meetings, the PS updated the teacher and school psychologist on the initial intervention targets for skills coaching.

Parent coach

During Phase 1, the PC met with Tyler's mother in their home. The goal of initial PC meetings was to build rapport and gather information on the strengths and needs of the family. Sessions focused on: (a) outlining his mother's goals for the transition, (b) identifying Tyler's strengths and his mother's strengths, (c) establishing and following homework routines, and (d) identifying anything else that she would like help with at home. His mother identified that goals for Tyler's transition were for him to have clean and sober friends at the new school and for him to complete his homework. She identified that Tyler was social, compassionate, and open to trying new things and that she was patient, engaged in his education, and consistent with consequences. Tyler did not have a consistent homework routine and his mother asked for help structuring such a routine. His mother identified that she also wanted assistance to increase his help with chores and improve his behavior at home by addressing his arguing, attitude, tone of voice, and use of cuss words.

Skills coach

Tyler met with the SC at the day-treatment school during Phase 1. Skills coaching sessions were coordinated with teachers to avoid disrupting instructional time. The goal of initial sessions was to identify areas of strength and ways to incorporate Tyler into school activities. Session activities included playing games (e.g., football, basketball), talking about Tyler's interests and self-identified strengths, and a snack. Tyler's interests were playing sports, skateboarding, rollerskating, and ways to make money by helping out in his neighborhood (e.g., collecting cans, helping with yard work). Although Tyler struggled to identify his own strengths, the SC observed that he was a positive leader in the classroom, a hard worker, and very personable.

School meetings

A transition planning meeting was held during Phase 1. Prior to the meeting, planning was completed with the school team, with Tyler's mother, and with Tyler. As mentioned, the PS met individually with the day-treatment transition teacher and the school psychologist at the neighborhood school to discuss their concerns for his transition. Their main concerns centered on Tyler's history of significant disruptive behavior and the neighborhood school's ability to provide a safe educational environment for him and his fellow students. The PC and Tyler's mother prepared for the meeting by outlining Tyler's strengths for the transition, reviewing her concerns about the transition, and identifying supports that she wanted at the neighborhood school to make the transition as successful as possible. Tyler's mother had a long history of challenging school/IEP meetings for both Tyler and his older brother. She reported that she felt as though the school staff talked down to her in meetings. She also shared that she was concerned that the transition planning meeting had taken a long time to schedule and was worried that the neighborhood school was delaying his transition because the staff did not want him there. The SC and Tyler prepared for the meeting by identifying his strengths and practicing by talking about his needs for the transition. Tyler reported that he felt ready to be at the neighborhood school full time.

The transition planning meeting was led by the transition teacher at the day-treatment school. Tyler, his mother, the SWIFT staff (PS, PC, and SC), and the school psychologist from the neighborhood school attended the meeting. After introductions at the start of the meeting, the PS briefly explained the SWIFT program and supports available for Tyler's transition. The school psychologist expressed enthusiasm for him to return and also raised concerns about Tyler's past behavior. Once the team agreed that the neighborhood school had sufficient supports in place to meet Tyler's academic and behavioral needs, they outlined a gradual transition plan. The plan started with a visit to the neighborhood school to meet teachers and tour the school. Once he had visited the school, the plan incorporated a slow integration into the school involving his attending the neighborhood school during the first two periods of the day and adding additional periods once he reported feeling confident and had demonstrated success as measured by consistently earning 80% of points on his daily point card. After the meeting, Tyler's mother indicated that preparing for the meeting helped her advocate for her son and helped her stay calm during difficult moments.

Phase 2: Skill Development and Practice

SWIFT participants spend the majority of Phase 2 time in student and parent skill development and practice. Phase 2 lasts for 6–9 months depending on the needs of the student and often includes support and engagement during the summer months.

Program supervision

During Phase 2, the SWIFT PS had regular email and phone contact with both the day-treatment and neighborhood school teams to keep all transition team members up-to-date and informed about Tyler's transition progress. Communication included updates on Tyler's progress with skills coaching interventions, helping the school team problem solve issues at school, and relaying pertinent information from home or school to all participants. In addition, the PS encouraged teachers and the school psychologist to contact Tyler's mother regularly with positive reports as well as any concerns. As Tyler progressed through his transition and added classes at the neighborhood school, the PS and school psychologist collaborated to help new teachers implement his support plan. The weekly supervision meeting was essential to ensure that the needs identified by teachers at both schools were integrated into weekly skills practice and that the parent was included in school-related decision making, especially when Tyler's behavioral data showed that he was ready to increase time at the neighborhood school.

Parent coach

During Phase 2, the PC and Tyler's mother problem solved parenting strategies to improve his behavior at home. His mother was open to suggestions while being clear about what would and would not work in her home. As the family progressed through Phase 2, the PC and Tyler's mother worked together to set up a chore chart, structure evening and homework routines, and design an incentive to reduce the frequency of Tyler's arguing and swearing. For example, Tyler's mother asked for help setting up an evening routine checklist to help Tyler remember to have his parents sign his daily school card, complete his daily chore, and follow his homework routine. When he completed the tasks on the checklist, he could choose a privilege from his choice list (i.e., play outside, friend time, TV time, earn money). The PC and Tyler's mother also problem solved strategies to facilitate regular contact with his teachers about his assignments and behavior at school. After a few months of participating in SWIFT, Tyler's mother reported that she felt more organized at home and that she had a system for emailing his teachers each week for a list of late assignments and assignments he needed to complete for the following week.

Skills coach

Skills coaching in Phase 2 included direct skill building related to the goals identified by Tyler, his parents, and teachers: reduce arguing and swearing, increase patience, and build study skills. To ensure contextual fit for all interventions, the content of skills coaching with Tyler was coordinated with parents and teachers. Sessions regularly included Tyler and the SC role-playing positive alternative responses to replace problem behaviors (e.g., complying with a request or asking for additional time to replace arguing). Later SC sessions included reinforcement (praise and contingent tangibles) for teacher reports about his use of positive alternative responses, additional practice, and problem solving for situations that were difficult. Since Tyler was an athletic student, his SC embedded skills practice within a game of basketball or “catch” to keep Tyler engaged.

School meetings

A school meeting took place at the neighborhood school the week before Tyler started attending morning classes in the resource room. The purpose of the meeting was for Tyler's mother to meet his resource room teacher, to introduce the SWIFT team and describe available supports, and to work with his resource room teacher to translate the accommodations and supports he was receiving at the day-treatment school to her classroom. Prior to the meeting, the PC helped Tyler's mother outline questions and suggestions she had for the teacher. Tyler's mother and the SWIFT team attended the meeting. Tyler did not attend because he had met the teacher during an earlier visit to the school.

When Tyler became a full-time student at the neighborhood school, the day-treatment school held a graduation for him. His graduation was attended by his mother, the teachers, students at the day-treatment school, and the SWIFT team. The comments from teachers and students reflected how well-liked and respected Tyler was at the school.

Phase 3: Maintenance

The third and final phase of SWIFT occurs once the student has fully transitioned to the neighborhood school. This phase lasts approximately eight weeks during which the SWIFT team fades supports. For Tyler, Phase 3 included the last few weeks of the summer break and lasted until his IEP meeting midway through the fall trimester.

Program supervision

The PS and school psychologist strategized the best way to fade SWIFT supports as Tyler maintained stability and engagement at the neighborhood school. During the weekly clinical supervision meeting, the PS encouraged the PC and SC to increasingly remind Tyler and his mother of their skills for maintaining stability at the neighborhood school during their weekly sessions.

Parent coach

During Phase 3, the PC provided positive feedback to Tyler's mother for her consistent communication with the school and problem solved strategies to maintain routines and her use of new parenting skills without SWIFT. For example, the SWIFT program had been helping to fund and deliver the incentive Tyler earned for using alternative responses to arguing and swearing. The PC and Tyler's mother developed a plan to maintain an incentive once the program ended.

Skills coach

The maintenance phase for Tyler focused on providing reinforcement for appropriate behavior at home and school. SC sessions continued to take place at the school and involved playing a game that he liked and providing incentives and positive feedback for the positive things that parents and the school team reported about his behavior in home and school settings. In final sessions they outlined goals for his future. Tyler identified that he wanted to become an electrician and was motivated to stay in school to be eligible for a job training program.

School meetings

Tyler's IEP meeting was held at the neighborhood middle school after his transition was complete. He was in the seventh grade. Prior to the meeting, the PS met with the school psychologist and resource teacher to discuss his progress and ongoing support needs. The PC and Tyler's mother met to outline his strengths and her concerns to share at the meeting. For example, his mother wanted to ask for a daily planner check to help track his assignments and for him to have a regular check-in/checkout routine. The SC and Tyler made a list of his school and career goals so that he could share them at the meeting.

The IEP meeting was led by the school psychologist and was attended by Tyler, his mother, SWIFT staff, and the special and general education teachers for each subject. Tyler shared his goals with the team at the start of the meeting and impressed his teachers with his confidence and articulation. His teachers agreed that Tyler was doing very well at the middle school both behaviorally and academically and the team updated his IEP to include additional mainstream classes with ongoing support in math and language arts. The school team agreed to his mother's request for the daily planner check and check-in/check-out routines. Finally, the team reviewed his behavioral data for the year and determined that he had met his behavior goal objectives and the behavior goal was removed from his IEP. His mother later reported that she was proud that Tyler was able to overcome his past reputation and experiences with the teachers and students.

SWIFT graduation

The timing for Tyler's graduation from SWIFT was based on his successful transition to the neighborhood school and the consistency of communication systems in place between school and home. Tyler's graduation from SWIFT was attended by his family, the SWIFT team, and teachers from both schools. The graduation served to highlight the progress Tyler had made over the past year and the skills he and his family used that resulted in his successful transition to the neighborhood school.

Student and Family Outcomes

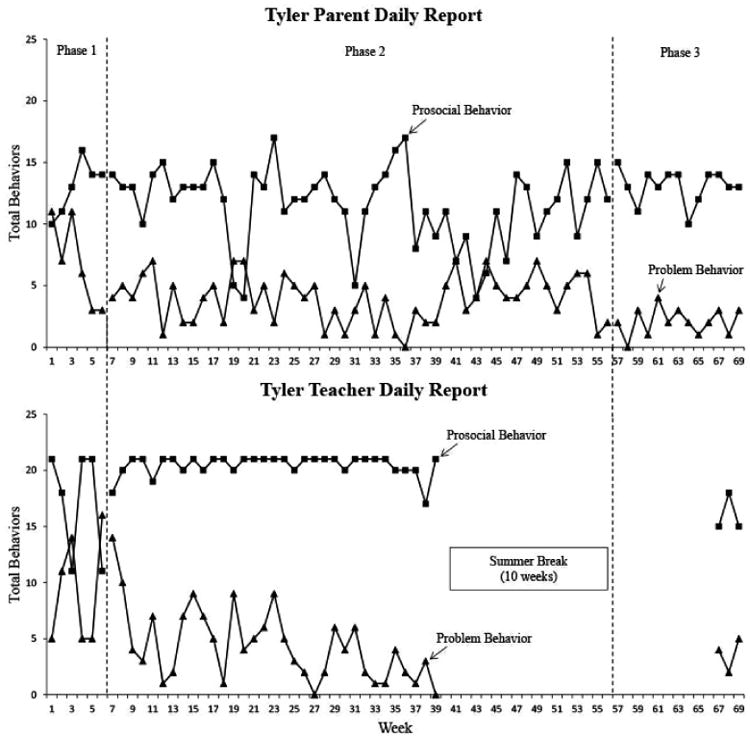

Tyler's behavior was measured using the PDR and TDR. Figure 1 shows a graph of the total number of problem and prosocial behaviors at home and at school during each phase. Data were collected once per week. During Phase 1, the total number of problem behaviors were similar at home (average = 7, range = 3 – 11) and at school (average = 9, range = 5 – 16). Tyler's prosocial behaviors were fairly high at home (average = 13, range = 10 – 16) and at school (average = 17, range = 11 – 21). In Phase 2, Tyler's behavior at school became more consistent and his problem behaviors decreased over time (average = 4, range = 0 – 14) while his prosocial behaviors increased (average = 20, range = 17 – 21). At home, Tyler's problem behavior decreased during the school months with a slight increase during the summer months (average = 4, range = 0 – 7). The increase in problem behavior over the summer months was mirrored by his prosocial behavior at home also decreasing slightly during that time (average = 12, range = 4 – 17). Tyler's mother suggested that the difference in his behavior during the summer might have been related to less structure over the summer break. In Phase 3, Tyler's problem behavior decreased at the end of the summer break and stayed low at home (average = 2, range = 0 – 4) and at school (average = 4, range = 2 – 5) until he graduated from SWIFT. His prosocial behavior remained high at both home (average = 13, range = 10 – 15) and school (average = 16, range = 15 – 18). The graphed PDR and TDR data (Figure 1) show that, overall, Tyler's behavior was appropriate at home and at school.

Figure 1.

Tyler's parent and teacher daily report graphs.

In addition to the PDR and TDR data, Tyler's mother was given a client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ) once every 3 months. The CSQ includes eight items, such as “How would you rate the quality of the service you received?” and “To what extent has our program met your needs?” Items are rated on a 1–4 Likert-type scale, resulting in a possible total score between 8--32. The average rating by Tyler's mother across three CSQs of 31.67 (SD = 0.58, range = 31.00 – 32.00) represents a consistently very high satisfaction score.

The PC and SC documented each contact with the family or the school staff. Table 1 presents a summary of the number, length, and type of contacts for Tyler and his mother by the PC and SC. The majority of the weekly sessions with Tyler and his mother were 30 min or longer. Tyler's contacts were typically one-on-one sessions, while contacts with his mother included one-on-one phone and text message.

Table 1. SWIFT Parent Coach and Skills Coach Contact Data.

| Parent Coach | Skills Coach | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of contacts | 65 | 44 |

| Session length (range) | 5 min–1 hr 50 min | 1 min–1 hr 45 min |

| % of sessions 30+ min | 58.5% | 88.6% |

| Person Contacted | ||

| Parent | 100.0% | 4.5% |

| Student | 16.9% | 100.0% |

| Teacher | 7.7% | .0% |

| Type of Contact | ||

| In-person 1:1 | 49.2% | 86.4% |

| School meeting | 7.7% | 4.5% |

| Phone | 13.8% | 2.3% |

| Text message | 26.2% | 2.3% |

| 0.0% | 0.0% |

To ensure social validity, qualitative interviews were conducted with parents and teachers to solicit feedback on the effectiveness of the intervention and how the SWIFT team could refine the supports to better meet their needs and the needs of students, families, and school teams. Qualitative data show that Tyler's mother thought that the PC was valuable for problem solving during weekly check-ins and that the PC made useful suggestions that were not “teachy” in nature. She shared that Tyler benefitted from one-on-one sessions with the SC and that she appreciated that the skills she identified were practiced during their time together. Qualitative data for teachers showed that they liked that Tyler had a team to attend meetings who knew him and his family. They also identified that Tyler and his mother benefitted from having individual supports customized to specific needs.

Conclusion

The SWIFT intervention emphasizes collaboration between home and school. A body of literature cites parent and educator collaboration as a best practice for serving students with emotional and behavioral disabilities (e.g., Epstein, Coates, Salinas, Sanders, & Simon, 1997; Sailor, Dunlap, Horner, & Sugai, 2009; Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2007). This paper is intended to provide an illustration of how to facilitate such collaboration based on three main lessons learned during an intervention trial.

First, we found that the key to successful collaboration between home and school is proactive communication. Such communication should occur not only between the parent and school, but also between the two school placements during the transition. Communication should be supported and encouraged between the parents and school teams from both placements to help with consistency across environments for academic and behavioral needs. Tyler's mother had a positive relationship with the day-treatment school team, but was apprehensive about communicating with the team at the neighborhood school even though she knew communication was critical for his success there. For Tyler, school meetings with all team members in attendance paired with proactive communication between the schools and home helped his team consistently provide the supports he needed to successfully transition to the neighborhood school.

Second, we learned that it is critical to take the time to build and cultivate relationships with everyone on the student's team. Building relationships includes understanding the existing relationships between school staff, learning the systems through which the student is served, and explaining the ways by which the student and school benefit from the supports offered. Our experience shows cultivating relationships to involve key stakeholders is critical to bring about the discussion of the student's needs and strengths early on and to increase the likelihood of a smooth transition. When key people were involved early, the family and student were able to access more local and state services and supports. When school staff turnover occurred, the SWIFT team capitalized on existing relationships to cultivate relationships with new staff. For example, SWIFT team members relied on the school psychologist to provide introductions to new teachers and navigate potentially tricky personnel dynamics at the school.

Finally, we learned that, even though team members might have different ideas about how to support the student, it is important to remember that we are on the same team. Conflicts can arise among team members with differing opinions about what is best for a student. To avoid or ameliorate conflict among Tyler's team members, it was helpful to use the student's strengths and quality of life as a guide for supporting the student's needs. The first school meeting for Tyler had the potential for conflict between the family and the school staff due to concerns regarding the severity of Tyler's prior behavior and his mother's frustration with what she perceived as the district's delaying his return. To proactively diffuse anticipated conflict, SWIFT staff emphasized that the goal was to meet Tyler's educational needs in the safest and most appropriate setting. This approach helped Tyler's mother report that reminders that the school team had his best interests in mind helped her focus on problem solving to meet his needs, rather than thinking that the school staff did not want him to attend his neighborhood school.

Although students moving from more restrictive to less restrictive environments can be at risk during such transitions, Tyler's case illustrates how a system of communication and supports can increase the likelihood of success in the new setting. The lessons learned about proactive communication, relationship building, and team collaboration outlined in this paper show how school practitioners can help facilitate the smooth integration of students transitioning into new environments. Tyler's case represents an example of a student transition that, despite a few bumps along the way, resulted in a very successful placement in a less restrictive environment.

Biographies

Rohanna Buchanan, PhD, is a Research Scientist at the Oregon Social Learning Center. Dr. Buchanan's research focuses on the inclusion of families and behavioral data to support youth in school. Her current research projects, funded through IES and NIDA, are in collaboration with child welfare and local school districts to test Students with Involved Families and Teachers (SWIFT), an intervention for children and adolescents during difficult transitions.

Traci Ruppert, MS, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Special Education at the University of Oregon. Ms. Ruppert's research interests include behavioral parent education, family-school partnerships, and designing academic instruction for students with low-incidence disabilities. She works on the SWIFT project at the Oregon Social Learning Center.

Tom Cariveau is a doctoral candidate in the Department of School Psychology at the University of Oregon. His research interests include the generalization and maintenance of behavior change, methods to promote treatment integrity in applied settings, and the treatment of problem behavior.

References

- Bradley R, Doolittle J, Bartolotta R. Building on the data and adding to the discussion: The experiences and outcomes of students with emotional disturbance. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2008;17:4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10864-007-9058-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. The Oregon Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care Model: Features, outcomes, and progress in dissemination. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2003;10:303–312. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80048-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JL, Coates L, Salinas KC, Sanders MG, Simon BS. School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, McWayne C, Perry MA, Childs S. Multiple dimensions of family involvement and their relations to behavioral and learning competencies for urban, low-income children. School Psychology Review. 2004;33(4):467–480. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Minke KM, Anderson KJ. Family-school collaboration and positive behavior support. Journal of Positive Behavioral Interventions. 2005;7:181–185. doi: 10.1177/10983007050070030701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sailor W, Dunlap G, Horner RH, Sugai G, editors. Handbook of positive behavior support. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Kratochwill TR. Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family-school connections and interventions. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Twenty-seventh annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: Author; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Friend M, Bursuck WD, Katash K, Duchnowski AJ, Sumi C, Epstein MH. Educating students with emotional disturbances: A national perspective on programs and services. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2006;14(1):12–30. doi: 10.1177/10634266060140010201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]