Abstract

Objective

To determine the relationship between negative margin width and locoregional recurrence (LRR) in a contemporary cohort of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) patients.

Background

Recent national consensus guidelines recommend an optimal margin width of 2 mm or greater for the management of DCIS; however, controversy regarding re-excision remains when managing negative margins < 2 mm.

Methods

One thousand four hundred ninety-one patients with DCIS who underwent breast-conserving surgery from 1996 to 2010 were identified from a prospectively managed cancer center database and analyzed using univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models to determine the relationship between negative margin width and LRR with or without adjuvant radiation therapy (RT).

Results

A univariate analysis revealed that age <40 years (n = 89; P = 0.02), no RT (n = 298; P = 0.01), and negative margin width <2 mm (n = 120; P = 0.005) were associated with LRR. The association between margin width and LRR differed by adjuvant RT status (interaction P = 0.02). There was no statistical significant difference in LRR between patients with <2 mm and ≥2 mm negative margins who underwent RT (10-yr LRR rate, 4.8% vs 3.3%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.2–3.2; P = 0.72). For patients who did not undergo RT, those with margins <2 mm were significantly more likely to develop a LRR than were those with margins ≥2 mm (10-yr LRR rate, 30.9% vs 5.4%, respectively; hazard ratio, 5.5; 95% CI, 1.8–16.8, P = 0.003).

Conclusions

Routine additional surgery may not be justified for patients with negative margins <2 mm who undergo RT but should be performed in patients who forego RT.

Keywords: breast conservation, ductal carcinoma in situ, local regional recurrence, margins

Controversy regarding the optimal margin width for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) has existed for several decades. The current consensus guidelines published by the Society of Surgical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend a margin threshold of 2 mm for DCIS. They also recommend the use of ‘‘clinical judgment’’ when determining whether patients with <2 mm margins should undergo re-excision, suggesting that patients who are at higher risk for recurrence should undergo re-excision.1 The risk of local regional recurrence (LRR) in contemporary DCIS patients treated with breast conservation surgery (BCS) followed by radiation therapy (RT) ranges from 5% to 10% at 10 years.2–5 Half of the recurrences that do occur are invasive.6–10 There are many known risk factors for LRR, including age, family history, nuclear grade, comedonecrosis, RT, and margin status.5,10–12 Of these, only RT and margin status are modifiable.

Four randomized clinical trials in the 1980s and 1990s examined the role of RT as an adjunct to BCS.13–16 An overview of these early trials indicated that RT reduced the absolute 10-year risk of LRR by 15.2% (12.9% vs 28.1%, P<0.00001).6 This benefit was seen regardless of age, tamoxifen use, tumor grade, comedonecrosis, tumor size, or margin status. While 3 of the 4 studies required negative margins for inclusion, the lack of standardized pathologic processing led to the inclusion of up to 18% of patients with positive or uncertain margins among the total population.17 In addition, varying thresholds and inconsistent pathologic processing were used to group margin status, making it difficult to draw conclusions about optimal margin width in patients undergoing RT.

Optimal margin width that can be regarded as negative without the need for re-excision is of great interest to surgeons as it is a modifiable risk factor for LRR. Two large meta-analyses have demonstrated that positive margins definitively increase the risk of LRR in patients with DCIS who are treated with RT.18,19 Wang et al18 found that patients with negative margins had a significantly lower risk of LRR than did patients with positive margins [odds ratio (OR), 0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.36–0.57; P < 0.001]. Dunne et al19 found a similar reduction in risk among patients with negative margins (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.27–0.47; P <0.0001). On the basis of these data, it is widely accepted that positive margins increase the risk of LRR. However, the threshold for optimal margin width is still unclear because of a limited amount of data.

Current consensus guidelines20 are based on grouped results from 4 studies that examined the outcomes of patients with margins of >0 or 1 versus ≥2 mm.21–24 Three of the 4 studies included historical cohorts dating back to the 1970s and were associated with significantly higher LRR rates than those currently seen in the modern era, with advances in breast imaging, standardized tissue processing, and utilization of RT. While the guidelines recommend the use of ‘‘clinical judgment,’’ emphasizing patient-centered evaluations for patients with margins < 2 mm, many multidisciplinary breast practitioners use this guideline as an absolute indication for re-excision. Therefore, in this study, we examined a contemporary cohort of DCIS patients who underwent standardized imaging, pathologic, and RT techniques to determine the risk of LRR among patients with close negative (<2 mm) versus free margins (≥2 mm) who did or did not undergo RT.

METHODS

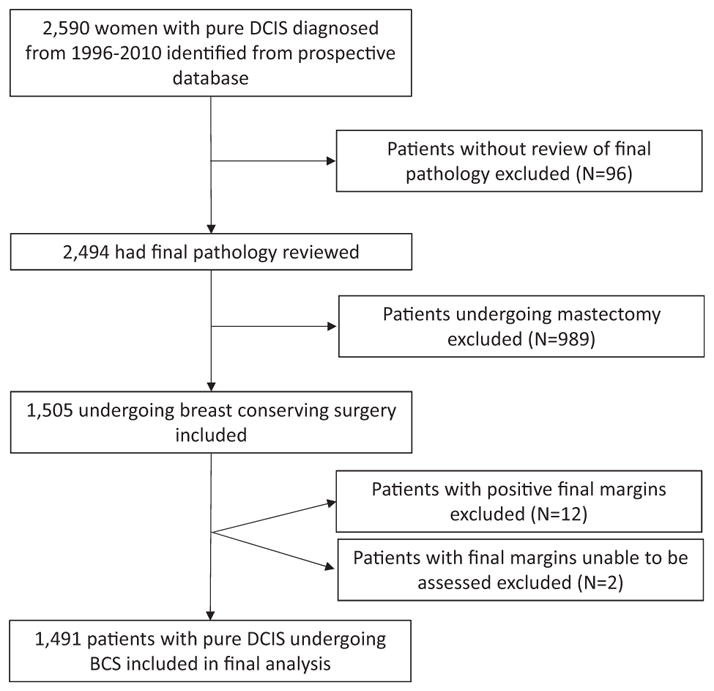

After receiving IRB approval, we identified 1503 patients who had been diagnosed with pure DCIS from January 1, 1996 to December 31, 2010 at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) and who had been identified via the prospectively managed MD Anderson Breast Cancer Management System Database. Only patients who had undergone BCS were included in the study. Patients who had undergone mastectomy and those whose surgical pathologic results were not reviewed at MD Anderson were excluded (Fig. 1). Demographic, clinical, pathologic, treatment, and follow-up variables were analyzed with respect to margin status at the time of definitive surgery for treatment of the initial diagnosis of DCIS. Patients with close margins (<2 mm) and free margins (≥2 mm) were included. Patients with positive margins (n = 12) were excluded. Patients with close margins (<2 mm) were divided into 2 groups, 0.01 to 1.00 mm and 1.01 to 1.99 mm for subgroup analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion criteria flowchart. All patients with pure DCIS diagnosed during the study period were identified. Patients without review of final pathology, undergoing mastectomy, final positive margins, or final margins unable to be assessed were excluded. BCS indicates breast conserving surgery.

Institutional standards for pathologic specimen processing were similar throughout the study period. Lumpectomy specimens had been inked with 6 different colors to separately identify each face of the specimen. The specimens had then been sectioned into 3 to 5-mm slices. The pathologist grossly examined each slice to determine the proximity of the lesion of concern to the margins. The slices had then been laid out sequentially in a standardized fashion and radiographed. A formal radiograph review was performed by the radiologist to determine the extent of radiographic abnormalities and their proximity to the margins. If concerning, a frozen section analysis had been performed, and if indicated, additional tissue margin had been excised. The final margin width had been based on an examination of formalin fixed, routinely processed, and paraffin-embedded tissue sections. The number of sections evaluated had been determined by the extent of gross and radiologic tissue abnormalities. The final margin width was reported in millimeters. In 2003, estrogen receptor status evaluated by immunohistochemistry became routinely incorporated into pathologic evaluation of DCIS cases; these data were also included and analyzed in our study.

Most patients [1193 (80%)] underwent RT following surgery. Of these, 38 patients in clinical trials underwent brachytherapy. The remainder underwent standard external beam RT. During the study period, RT following BCS at our institution consisted of 50 Gy in 25 fractions to the whole breast, followed by a tailored 10 to 14 Gy boost to the tumor bed (14 Gy in 7 fractions for patients with close margins <2 mm and 10 Gy in 5 fractions for patients with more widely negative margins).

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used to test the differences among categorical variables. Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to detect differences among continuous variables. The distribution of time to LRR was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Log-rank tests were performed to test the differences in survival between groups. Cox regression models were used to investigate the association between margin width and LRR while adjusting for other baseline variates. Patients who did not experience a LRR were censored at the time of last contact or death. A multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was developed by first including adjuvant RT and margin width in the univariate analysis, regardless of their P values, along with a set of candidate predictor variables with P values <0.10. A backward elimination was then performed, using 0.05 for the significance level of the Wald chi-square, to determine which effects remained in the final model. We further assessed the interaction effect of adjuvant RT and margin width on LRR. The purpose of this analysis was to determine whether the magnitude or direction of the association between margin width and LRR differed with the use of adjuvant RT. Martingale residuals were used to check the Cox proportional hazards model assumption for the continuous variables, including age at diagnosis and pathologic tumor size.25–28 All statistical computations were performed using SAS software version 9.4 and S-Plus version 8.2.

RESULTS

Baseline patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics were examined (Table 1). The median follow-up time was 8.7 years. Overall, the median age was 56 years (range, 18–89 yrs). Most patients [1193 (80%)] underwent adjuvant RT, and (44.9%) received adjuvant hormonal therapy. Most patients (1371, 92.0%) had free margins (≥2 mm) on final pathologic analysis, and 120 had close negative margins (<2 mm). Of the patients with close margins, 99 had margins of ≥1 mm and 21 had margins of 1 to 2 mm. Of the patients with close negative margins of < 2 mm, 89 patients had only 1 close negative margin, 22 patients had 2 close negative margins, and 9 patients had ≥3 close negative margins. Overall, 3.4% of patients (51 of 1491) had an LRR.

TABLE 1.

Demographic, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics of Patients Who Underwent Breast-conserving Surgery

| Characteristic | Entire Study Cohort, n (%)* (n = 1491) | Radiation Therapy, n (%)* (n = 1193) | No Radiation Therapy, n (%)* (n = 298) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 1491 | 1193 | 298 |

| Median age, yr (range) | 56 (18–89) | 55 (23–86) | 58 (18–89) |

| ≤40 | 89 (6.0) | 72 (6.0) | 17 (5.7) |

| >40 | 1402 (94.0) | 1121 (94.0) | 281 (94.3) |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Pre | 354 (23.7) | 291 (24.4) | 63 (21.1) |

| Post | 1126 (75.5) | 892 (74.8) | 234 (78.5) |

| Peri | 5 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Unknown | 6 (0.4) | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Family history | |||

| No | 810 (54.3) | 663 (55.6) | 147 (49.3) |

| Yes | 681 (45.7) | 530 (44.4) | 151 (50.7) |

| First degree | |||

| No | 1209 (81.1) | 979 (82.1) | 230 (77.2) |

| Yes | 281 (18.9) | 213 (17.9) | 68 (22.8) |

| Nuclear grade | |||

| Low/intermediate | 809 (54.3) | 592 (49.6) | 217 (72.8) |

| High | 647 (43.4) | 579 (48.5) | 68 (22.8) |

| Unknown | 35 (2.3) | 22 (1.8) | 13 (4.4) |

| Median tumor size, cm (range) | 1.0 (0.01–12.5) | 1.0 (0.01–12.5) | 0.6 (0.05–6.6) |

| ≤1 cm | 670 (44.9) | 506 (42.4) | 164 (55.0) |

| >1 cm | 502 (33.7) | 451 (37.8) | 51 (17.1) |

| Unknown | 319 (21.4) | 236 (19.8) | 83 (27.9) |

| Comedo | |||

| Absent | 1023 (68.6) | 789 (66.1) | 234 (78.5) |

| Present | 393 (26.4) | 342 (28.7) | 51 (17.1) |

| Unknown | 75 (5.0) | 62 (5.2) | 13 (4.4) |

| Necrosis | |||

| Absent | 948 (63.6) | 735 (61.6) | 213 (71.5) |

| Present | 520 (34.9) | 443 (37.1) | 77 (25.8) |

| Unknown | 23 (1.5) | 15 (1.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| RT | |||

| No | 298 (20.0) | — | — |

| Yes | 1193 (80.0) | — | — |

| Hormone therapy | |||

| No | 822 (55.1) | 600 (50.3) | 222 (74.5) |

| Yes | 669 (44.9) | 593 (49.7) | 76 (25.50) |

| Estrogen receptor status | |||

| Positive | 849 (56.9) | 704 (59.0) | 145 (48.7) |

| Negative | 157 (10.5) | 138 (11.6) | 19 (6.4) |

| Unknown | 485 (32.5) | 351 (29.4) | 134 (45.0) |

| Margin width | |||

| Close (<2 mm) | 120 (8.1) | 100 (8.4) | 20 (6.7) |

| Free (≥2 mm) | 1371 (91.9) | 1093 (91.6) | 278 (93.3) |

Except where indicated.

In comparison to patients who did not undergo RT, patients who underwent RT were more likely to have tumors >1 cm, high nuclear grade (III), comedonecrosis, and have undergone adjuvant hormonal therapy. The median age of patients undergoing RT was 55 years versus 58 years for patients not undergoing RT (P = 0.004). The median pathologic tumor size in patients undergoing RT was 1.0 cm versus 0.6 cm in patients not undergoing RT (P ≥ 0.001). Patients who underwent adjuvant hormonal therapy were more likely to have also undergone adjuvant RT. Patients undergoing adjuvant hormonal therapy were more likely to have hormone receptor-positive disease and a low nuclear grade (I or II).

Age <40 years and adjuvant RT were associated with increased LRR on the basis of the univariate Cox proportional hazards model (Table 2). Interaction effects between margin width and adjuvant RT, or adjuvant hormone therapy were investigated in the multivariable Cox model adjusting for age. There was a statistically significant interaction effect for margin width and adjuvant RT (P = 0.02). The final multivariate Cox proportional hazards model included age, margin width, adjuvant RT, and the interaction between margin width and RT. Among patients who underwent adjuvant RT, patients with a negative margin width of <2 mm had no significantly higher risk of LRR than did those with ≥2 mm [hazard ratio (HR), 0.77; 95% CI, 0.19–3.23, P = 0.72] (Table 3). However, patients who did not undergo adjuvant RT had a significantly higher risk of LRR (HR, 5.49; 95% CI, 1.79–16.88, P = 0.003) (Table 3). Furthermore, patients with close negative margins (n = 99) of 0.01 to 1.00 mm had a further increased risk compared with those with ≥2 mm for LRR among patients who did not undergo adjuvant RT (HR, 7.18; 95% CI, 2.34–21.98, P = 0.0006). This risk was not seen in patients with margins of 0.01 to 1.0 mm who underwent RT (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.31–4.28, P = 0.84).

TABLE 2.

Univariate Analysis of the Association Between Clinical and Pathologic Factors and Local Regional Recurrence

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | |||

| ≤40 | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| >40 | 0.4 | 0.18–0.88 | 0.02 |

| Family history | |||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Yes | 1.19 | 0.69–2.07 | 0.53 |

| First degree | |||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Yes | 0.82 | 0.39–1.75 | 0.61 |

| Nuclear grade | |||

| Low or intermediate | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| High | 1.03 | 0.59–1.79 | 0.93 |

| Tumor size | |||

| ≤1 cm | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| >1 cm | 1.52 | 0.80–2.90 | 0.2 |

| Comedo | |||

| Absent | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Present | 0.77 | 0.40–1.51 | 0.45 |

| Necrosis | |||

| Absent | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Present | 0.67 | 0.36–1.26 | 0.22 |

| Radiation therapy | |||

| Yes | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| No | 2.28 | 1.28–4.05 | 0.01 |

| Hormone therapy | |||

| No | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Yes | 0.63 | 0.35–1.13 | 0.12 |

| Hormone receptor status | |||

| Positive | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Negative | 0.75 | 0.22–2.50 | 0.64 |

| Margin width | |||

| Free (≥2 mm) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Close (<2 mm) | 1.7 | 0.73–4.00 | 0.22 |

| Margin width | |||

| Free (≥2 mm) | 1.00 (reference) | — | — |

| Close (1.1–1.9 mm) | 0.81 | 0.05–13.7 | 0.88 |

| Closest (≤1 mm) | 2.21 | 0.96–5.09 | 0.17 |

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazard Models of Local Regional Recurrence Among Patients Who Did and Did Not Undergo Radiation Therapy*

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation therapy | |||

| Age, yrs | |||

| >40 | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| ≤40 | 2.72 | 1.05–7.06 | 0.04 |

| Margin width | |||

| Free (≥2 mm) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Close (<2 mm) | 0.77 | 0.19–3.23 | 0.72 |

| No radiation therapy | |||

| Age, yrs | |||

| >40 | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| ≤40 | 2.08 | 0.48–9.08 | 0.33 |

| Margin width | |||

| Free (≥2 mm) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| Close (<2 mm) | 5.49 | 1.79–16.88 | 0.003 |

Variables in the model included: age, radiation therapy, margin width.

Figure 2 shows Kaplan–Meier plots for LRR among patients with close negative versus free margins among all patients, patients who underwent RT, and patients who did not undergo RT. While there was no difference in the incidence of LRR among patients with close negative versus free margins in the overall cohort, there was a significant difference when the cohort was separated into patients who did and did not undergo RT. This difference was not seen among patients who underwent RT (Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Local regional recurrence among patients with DCIS treated with breast conserving surgery with and without radiation therapy. A, All patients. B, Patients with RT. C, Patients without RT. Green line represents patients with margins < 2 mm. Blue line represents patients with margins ≥ 2 mm.

TABLE 4.

Predictors of 10-yr Local Regional Recurrence Rates in Patients With Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Treated With Lumpectomy, With and Without Radiation Therapy

| Adjuvant Radiation Therapy

|

No Adjuvant Radiation Therapy

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Events/Total | 10-Yr Local Regional Recurrence Rate | P Value | Events/Total | 10-Yr Local Regional Recurrence Rate | P Value |

| All patients | 33/1193 | 3.5% (2.4%, 5.1%) | 28/298 | 6.7% (4.2%, 10.7%) | ||

| Age, yrs | ||||||

| ≤40 | 5/72 | 10.0% (4.1%, 23.5%) | 0.03 | 2/17 | 15.6% (4%, 50.7%) | 0.26 |

| >40 | 28/1121 | 3.0% (2%, 4.6%) | 16/281 | 6.2% (3.8%, 10.2%) | — | |

| Family history | ||||||

| No | 15/662 | 2.4% (1.3%, 4.2%) | 0.19 | 11/147 | 7.7% (4.2%, 13.9%) | 0.35 |

| Yes | 18/530 | 4.9% (3%, 8.1%) | 7/151 | 5.8% (2.8%, 12%) | — | |

| First degree relative with breast cancer | ||||||

| No | 28/979 | 3.4% (2.2%, 5.1%) | 0.74 | 15/230 | 6.9% (4.1%, 11.5%) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 5/213 | 3.9% (1.6%, 9.4%) | 3/68 | 6.0% (1.9%, 18%) | — | |

| Nuclear grade | ||||||

| Low or intermediate | 17/592 | 3.8% (2.2%, 6.4%) | 0.98 | 11/217 | 5.5% (3%, 10%) | 0.19 |

| High | 16/579 | 3.2% (1.8%, 5.5%) | 6/68 | 10.9% (4.9%, 23.4%) | — | |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| ≤1 cm | 8/506 | 1.5% (0.7%, 3.2%) | 0.055 | 10/164 | 6.5% (3.4%, 12.2%) | 0.42 |

| >1 cm | 15/451 | 4.1% (2.3%, 7.3%) | 4/51 | 10.6% (4.1%, 26.3%) | — | |

| Comedo | ||||||

| Absent | 26/789 | 2.6% (1.2%, 5.7%) | 0.39 | 14/232 | 6.8% (4%, 11.5%) | 0.62 |

| Present | 7/342 | 4.0% (2.6%, 6.3%) | 4/51 | 8.3% (3.2%, 20.6%) | — | |

| Necrosis | ||||||

| Absent | 22/735 | 4.0% (2.6%, 6.3%) | 0.8 | 16/213 | 8.0% (4.9%, 13%) | 0.16 |

| Present | 11/443 | 2.4% (1.2%, 4.6%) | 2/77 | 3.4% (0.8%, 13.4%) | — | |

| Hormone therapy | ||||||

| No | 20/600 | 4.3% (2.7%, 6.8%) | 0.34 | 14/222 | 7.6% (4.5%, 12.7%) | 0.65 |

| Yes | 13/593 | 2.6% (1.4%, 5%) | 4/76 | 4.3% (1.4%, 12.8%) | — | |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||||||

| Positive | 13/704 | 2.3% (1.2%, 4.2%) | 0.7 | 8/145 | 5.6% (2.7%, 11.4%) | 0.98 |

| Negative | 2/138 | 1.5% (0.4%, 5.7%) | 1/19 | 5.9% (0.9%, 35%) | — | |

| Margin width | ||||||

| Free (≥2 mm) | 31/1093 | 3.3% (2.2%, 4.9%) | 0.69 | 14/278 | 5.4% (3.1%, 9.2%) | 0.0006 |

| Close (<2 mm) | 2/100 | 4.8% (1.2%, 18.5%) | 4/20 | 30.9% (12.4%, 64.6%) | — | |

We calculated 10-year LRR rates for patients who had and had not undergone adjuvant RT. Among patients who had undergone RT, there was no significant difference in the 10-year LRR among patients with close margins and patients with free margins (4.8% vs 3.3%). However, among patients who did not undergo RT, there was a significant difference in 10-year LRR (30.9% vs 5.4%). Patients ≤40 years who had undergone RT had a 10% risk of LRR at 10 years compared with 3% in patients aged >40 years (P = 0.03). This difference in 10-year LRR remained for patients aged ≤40 years versus >40 years who did not undergo RT (15.6% vs 6.2%) but was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

On the basis of the results of this large single-center, contemporary study of patients with DCIS who underwent BCS with standardized imaging, pathologic processing, surgical, and RT techniques, we conclude that patients aged <40 years and patients who do not undergo RT with margins < 2 mm are at the highest risk of LRR. To our knowledge, this is the largest contemporary study to specifically examine the difference in LRR among patients with pure DCIS who underwent BCS with close negative versus free margins. Like many previous studies, we found that age, RT, and margin width had a significant effect on LRR. Furthermore, we found no difference in LRR among patients undergoing RT with close versus free margins. However, there was a significant increase in the 10-year LRR rate among patients who did not undergo adjuvant RT. To further investigate this increased risk, we subdivided the close margin group and examined risk by margins of 0 to 1 mm. The increased risk of LRR was even higher among these patients who did not undergo RT, and was not seen in patients who had undergone RT. In multivariate analyses, age ≤40 years was an independent risk factor for LRR among patients who underwent RT compared with age >40 years; these findings indicate that additional multidisciplinary considerations for re-excision are warranted for margins <2 mm in these patients.

A recent study-level meta-analysis by Marinovic et al20 examined the association between surgical margins and LRR in women with DCIS who had been treated with BCS. Twenty retrospective studies performed over a 50-year period (1968–2010) met the inclusion criteria, and 7883 patients were included. The median mid-point year for studies included in the meta-analysis was 1991. The prevalence of LRR was 8.3%, with a median follow-up of 6.5 years. Overall, 71% of patients underwent whole-breast RT, and 20.8% of patients underwent endocrine therapy. Using random effects logistic metaregression modeling, the OR for the LRR rate between the negative versus positive or close margin groups was 0.53 (95% CI, 0.45–0.62; P<0.001). The definition of a positive margin was highly variable among studies, and there was no standardized pathologic processing method among the different studies. A positive margin was defined as 0 mm in 9 studies, <1 mm in 7 studies, <2 mm in 3 studies, and <3 mm in 1 study.

Because of the discrepancy in definition of positive margins, a Bayesian network meta-analysis was used to allow single and multiple cut-points per study. Four studies were identified to compare LRR rates among patients with margins of >0 or 1 mm compared with 2 mm.20–24 ORs with 95% credible intervals were calculated for patients with negative margins relative to those with positive margins. For patients with negative margins of >0 or 1 mm, the OR was 0.45 (95% CrI, 0.32–0.61) compared with that for patients with positive margins. For patients with negative margins of ≥2 mm, the OR was 0.32 (95% CrI, 0.21–0.48). These findings did not differ when patients who did not undergo RTwere excluded. The difference in ORs between these 2 groups was quite small, and the authors acknowledged that the model may have exaggerated the differences among smaller threshold categories, such as >0 or 1 and 2 mm in this example.

Of the 4 studies, 3 included patients dating back to the 1970s. Using a multivariable Cox regression analysis to study the association between margin width and recurrence, investigators at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center found a significantly higher risk of LRR (HR, 1.47) among patients who underwent surgery between 1978 and 2000 than among patients who underwent surgery between 2001 and 2010 (P = 0.002).21 When stratifying patients by time period, the risk of LRR was increased among the older cohort of patients who underwent surgery but not RT between the years 1978 to 2000 compared with patients treated between 2001 and 2010 (HR, 1.60; P = 0.003). Similar to our study, Van Zee et al found that there was no significant difference in the LRR rate between patients who underwent RT with close margins (≤2 mm) and those with wide margins (>2–10 mm) (HR, 0.95 vs 1.00; P = 0.95). In contrast, patients who did not undergo adjuvant RT had a slightly higher risk of LRR with close margins than with larger margins (HR, 0.75 vs 0.58; P < 0.0001).

In our previous smaller study reported in 2012 on patients with DCIS who underwent BCS from 1996 to 2009, age < 40 years, pathologic tumor size ≥1.5 cm, and no RT were associated with a significantly higher LRR rate on univariate analysis.29 On multivariate analysis, these 3 variables were associated with an increased HR for LRR, which remained statistically significant. In that study, margins were grouped into negative versus close or positive, and there was no statistically significant difference in the LRR rate between the 2 groups. This is likely because only 4 patients had positive margins, and most patients (80.3%) underwent RT. The study reported in 2012 was not included in the recent meta-analysis. In the current study, the number of patients included was larger and the median length of follow-up time was longer. Patients with positive margins were excluded, and patients with close negative stratified by degree of margin width versus free margins were compared. Given the interaction effect between RT and margins, LRR rates were dramatically higher in younger patients with close margins than in those with free margins who did not undergo RT. However, this difference was not seen among patients who underwent RT. Taking the results of the present study together with the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group overview of trials in radiotherapy for DCIS (which did not specifically address width of negative margins), there appears to be no independently associated risk of local recurrence by younger age among patients not receiving radiotherapy but a significant reduction in local recurrence risk for older compared with younger women who receive radiotherapy for DCIS.6

Recent consensus guidelines from the Society of Surgical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and American Society of Clinical Oncology recommend the standard use of a 2-mm margin in DCIS patients undergoing BCS and whole-breast RT.1 They recommend using clinical judgment when determining the need for surgery in patients with margins between 0 and 2 mm. The decision to use the 2 mm threshold rather than >0 mm was based on the results of the meta-analysis discussed above, with weak evidence of a reduction in LRR among patients with margins >2 mm found in the Bayesian model (ROR, 0.72; 95% CrI, 0.47–1.08), which did not reach statistical significance.

One important caveat and potential limitation of our study is that our findings may not be broadly applicable to patients who are treated at other centers or who undergo components of their diagnosis and therapy at multiple different centers that do not use similar multidisciplinary practice guidelines. Although the number of patients in the less than 2 mm group is modest, this number of patients is not small and the comparison group with margins 2 mm and greater is large. Therefore it is hard to argue that a larger sample size will demonstrate a significant difference between two different margin groups among RT patients. A cautionary note on this observation is the modest number of patients in the cohort with less than 2 mm margins together with an overall low rate of LRR, so that it can be underpowered to detect a small difference in LRR between free and close margin groups. Our findings suggest that patients with close margins (<2 mm) who forego RT should undergo re-excision to achieve margins of ≥2 mm. In patients undergoing RT, re-excision offers no benefit in the 10-year LRR rate in patients with close negative margins compared with that in patients with free margins. Together with the present findings, the new consensus guidelines provide surgeons and multidisciplinary teams with a potential framework for individualizing therapy, weighing the potential risks versus benefits of additional surgery against the absolute risk of LRR, which are likely to be higher in patients <40 years, those with multiple close margins, and those foregoing RT. Finally, in the case of close but negative margins, postsurgical mammography is indicated to ensure the complete excision of malignant-appearing calcifications. Further contemporary multicenter, prospective studies with additional follow-up are needed to ensure that the findings of this study are applicable to a large, more heterogeneous population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann Sutton from the Department of Scientific Publications for editorial assistance with this manuscript.

This work was supported by the PH and Fay Etta Robinson Distinguished Professorship in Cancer Research (HMK) and Biostatistics Resource Group of Cancer Center Support Grant from NIH (CA16672). This study was partially funded by a generous gift from Caroline and Stuart Palmer.

The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 2017 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 4, 2017. ABT is the recipient of the 2017 Conquer Cancer Foundation Merit Award for this work.

The content of this report is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Dr HMK had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Morrow M, Van Zee KJ, Solin LJ, et al. Society of surgical oncology-American Society for Radiation Oncology-American Society of Clinical Oncology consensus guideline on margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in ductal carcinoma in situ. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3801–3810. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5449-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai HX, Motwani SB, Higgins SA, et al. Breast conservation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): does presentation of disease affect long-term outcomes? Int J Clin Oncol. 2014;19:460–466. doi: 10.1007/s10147-013-0575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaitelman SF, Wilkinson JB, Kestin LL, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast-conserving therapy: implications for optimal follow-up strategies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:e305–e312. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.12.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yi M, Meric-Bernstam F, Kuerer HM, et al. Evaluation of a breast cancer nomogram for predicting risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ after local excision. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:600–607. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vargas C, Kestin L, Go N, et al. Factors associated with local recurrence and cause-specific survival in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:1514–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C, et al. Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:162–177. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Pinder SE, et al. Effect of tamoxifen and radiotherapy in women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ: long-term results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:21–29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70266-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donker M, Litiere S, Werutsky G, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4054–4059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Warnberg F, Garmo H, Emdin S, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ: 20 years follow-up in the randomized SweDCIS Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3613–3618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:478–488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCormick B, Winter K, Hudis C, et al. RTOG 9804: a prospective randomized trial for good-risk ductal carcinoma in situ comparing radiotherapy with observation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:709–715. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ER, Land SR, Saad RS, et al. Pathologic variables predictive of breast events in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:86–91. doi: 10.1309/WH9LA543NR76Y29J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fisher B, Dignam J, Wolmark N, et al. Lumpectomy and radiation therapy for the treatment of intraductal breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-17. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:441–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houghton J, George WD, Cuzick J, et al. Radiotherapy and tamoxifen in women with completely excised ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK, Australia, and New Zealand: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13859-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emdin SO, Granstrand B, Ringberg A, et al. SweDCIS: Radiotherapy after sector resection for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Results of a randomised trial in a population offered mammography screening. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:536–543. doi: 10.1080/02841860600681569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Julien JP, Bijker N, Fentiman IS, et al. Radiotherapy in breast-conserving treatment for ductal carcinoma in situ: first results of the EORTC randomised phase III trial 10853. EORTC Breast Cancer Cooperative Group and EORTC Radiotherapy Group. Lancet. 2000;355:528–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)06341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher ER, Dignam J, Tan-Chiu E, et al. Pathologic findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast Project (NSABP) eight-year update of Protocol B-17: intraductal carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:429–438. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990801)86:3<429::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SY, Chu H, Shamliyan T, et al. Network meta-analysis of margin threshold for women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:507–516. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunne C, Burke JP, Morrow M, et al. Effect of margin status on local recurrence after breast conservation and radiation therapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1615–1620. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marinovich ML, Azizi L, Macaskill P, et al. The association of surgical margins and local recurrence in women with ductal carcinoma in situ treated with breast-conserving therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3811–3821. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5446-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Zee KJ, Subhedar P, Olcese C, et al. Relationship between margin width and recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ: analysis of 2996 women treated with breast-conserving surgery for 30 years. Ann Surg. 2015;262:623–631. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solin LJ, Fourquet A, Vicini FA, et al. Long-term outcome after breast-conservation treatment with radiation for mammographically detected ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 2005;103:1137–1146. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues N, Carter D, Dillon D, et al. Correlation of clinical and pathologic features with outcome in patients with ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1331–1335. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03747-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Turaka A, Freedman GM, Li T, et al. Young age is not associated with increased local recurrence for DCIS treated by breast-conserving surgery and radiation. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:25–31. doi: 10.1002/jso.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Statistic Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Woolson RF, Clarke WR. Statistical Methods for the Analysis of Biomedical Data. 2. New York, Chichester: Wiley; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantel N. Evaluation of survival date and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chem Rep. 1966;5:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion) JR Statist Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarado R, Lari SA, Roses RE, et al. Biology, treatment, and outcome in very young and older women with DCIS. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3777–3784. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2413-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]