Abstract

Objective

This study examines the effect of physician medical malpractice liability exposure on primary Cesarean and vaginal births after Cesarean (VBACs).

Data Sources/Study Setting

Secondary data on hospital births from Florida Hospital Inpatient File, physician characteristics from American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, and physician malpractice claim history from Florida Office of Insurance Regulation.

Study Design

Our study estimates the effects of physician malpractice liability exposure on Cesareans and VBACs using panel data and a multivariate, fixed effects model.

Data Collection

We merge three secondary data sources based on unique physician license numbers between 1994 and 2010.

Principal Findings

We find no evidence that the first malpractice claim affects primary Cesarean deliveries. We find, however, that the first malpractice claim decreases the likelihood of a VBAC (conditional on a prior Cesarean delivery) by 1.2–1.9 percentage points (approximately 10 percent relative to mean VBAC incidence). This finding is robust to focusing on obstetrics‐related malpractice claims, as well as to considering different malpractice claims (first report, first severe report, and first lawsuit).

Conclusions

Given the increase in both primary and repeat Cesarean deliveries, our results suggest that physician malpractice liability exposure is responsible for a relatively small share of the VBAC decrease.

Keywords: Medical malpractice, defensive medicine, Cesarean, vaginal births after Cesarean, physician liability

Between 1996 and 2012, the national Cesarean delivery rate increased from 21 to 33 percent (Martin et al. 2013). Cesarean deliveries increased for all women by age, racial/ethnic categories, and infant gestational age. Cesarean birth is more expensive than a vaginal birth and associated with higher rates of surgical complications, maternal hospitalization, and NICU admission (Kamath et al. 2009). Without complications, the average cost of a Cesarean delivery was approximately $15,799, compared with $9,617 for a vaginal delivery (HCUP, 2009). Cesarean deliveries are associated with longer hospital stays, and in turn higher health care costs (HCUP, 2009), as well as higher morbidity/mortality for the mother and infant. Increases in elective Cesareans are one factor affecting the rise in Cesarean births over time and increase in health care costs. A back‐of‐the‐envelope calculation suggests that the cost of the 12 percentage point increase in Cesarean delivery between 1996 and 2012 is approximately $2.9 billion per year.1

The increase in Cesarean births is partly due to reductions in vaginal births after Cesarean (VBACs). During the 1990s, the rate of VBAC peaked at over 30 percent but has now dropped to below 10 percent (ACOG 2010). A 2001 study found that VBAC had increased risks related to uterine rupture (Lydon‐Rochelle et al. 2001). Price and Simon (2009) use the timing of this information release to explain the drop in VBAC rates (a reduction of 16 percent, primarily among educated mothers). More recent studies have found that risk to be low and that successful VBACs are possible for some women, for example, previous successful vaginal birth, spontaneous labor, birth weight <4,000 g, and Caucasian women (Ebell 2007). In 2010, the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG 2010) released an updated Practice Bulletin indicating that a trial of labor after Cesarean (TOLAC) and subsequent VBAC is safe for most women with a previous Cesarean (one previous Cesarean and low transverse incision), and 60–80 percent could deliver successfully by VBAC. The risk of uterine rupture is serious with TOLAC/VBAC, but the probability of occurrence is <1 percent (ACOG 2010). Hospital or insurer‐level preferences over TOLAC and VBAC, physician and patient preferences/decisions, and the medical liability environment have contributed to the dramatic decline in VBACs (ACOG 2010; Grobman et al. 2011). “Once a Cesarean, always a Cesarean” has again become the norm. These changes in VBAC rates are a contributor to the high rate of Cesarean deliveries, which again raises concerns about costs and complications.

Malpractice liability and defensive medicine also may affect physician treatment decisions (Yang et al. 2009). Defensive medicine occurs when physicians order tests or procedures to reduce liability, where such tests provide no medical benefits. For obstetrics, malpractice liability is believed to have partly contributed to the increase in Cesarean deliveries and decrease in VBACs. We view a shift from vaginal to Cesarean birth as possible evidence of defensive medicine, but with hospital discharge data, it is difficult to observe concurrent changes in maternal/infant outcomes. Physician response to malpractice liability may also be reflected through reductions in VBACs, as VBACs may be perceived as more risky.

The existing literature has focused on the effect of malpractice at an aggregate level (e.g., state‐level insurance premiums, tort reform presence) and the physician level (e.g., individual malpractice claims). Here, we limit our discussion to those papers that measure malpractice liability at the individual physician level. Each of these studies uses Florida hospital discharge data merged with medical malpractice claims data (similar data to our own study). Using a short panel of 1992–1995 data, Grant and McInnes (2004) model the relationship between physician malpractice liability and Cesarean delivery, finding a small effect of malpractice claims on risk‐adjusted Cesarean delivery rates. Gimm (2010), using 1992–2000 data, considers the effect of any malpractice claims on delivery volume and Cesarean delivery rates. He finds no evidence that physicians change their Cesarean delivery rates in response to malpractice claims. Dranove and Watanabe (2010) study the effect of malpractice liability (based on contact about a potential lawsuit) on Cesarean deliveries using data from 1994 to 2000. The authors consider malpractice liability exposure in three ways—liability of the physician, hospital, and the area (county)—by constructing discounted cumulative histories of malpractice liability exposure at each level. The results suggest small, positive, short‐lived effects on Cesarean delivery (mostly for hospital but sometimes for physician liability exposure). Shurtz (2012) studies the relationship between medical errors and Cesarean delivery. In his study, medical errors are defined as adverse events that lead to lawsuits. Shurtz finds that physician Cesarean delivery rates increase discontinuously (4 percent) after an adverse event and continue to increase afterward.

Our study estimates the effects of physician malpractice liability exposure on Cesarean births and VBACs. We examine the census of hospital births in Florida from 1994 to 2010 and the malpractice liability experiences of the physicians performing those deliveries using a panel dataset and a multivariate fixed effects model. Our study is the first to examine individual‐level physician malpractice liability exposure on the likelihood of VBAC in addition to primary Cesareans, as well as identify incidents that are obstetric and labor/delivery‐related, focusing on the most relevant liability experience. We also utilize a longer data period, which allows us to examine effects for the 1990s and 2000s separately, when VBAC rates decreased considerably. Finally, we identify the potential effect of malpractice liability by focusing on the physician's first claim, rather than any claim. We consider malpractice claims based on the timing of the first contact about a potential lawsuit and the actual filing of a lawsuit (if filed). The physician's first liability experience has the potential to have the most meaningful effect on delivery decisions. The majority of physicians with malpractice claims in our sample have only experienced one claim. Because we want to identify the first malpractice claim, we exclude physicians who had malpractice claims before 1994, our first year of linked hospital data. We observe, therefore, the entire malpractice history for the physicians, who, given their observed practice experience, are most likely to change their behavior in response to malpractice pressure, if at all.

Study Data and Methods

Data

In this study, we employ three main sources of data that we merge by physician's unique Florida license number. We limit the analysis to include all hospital births delivered by a physician in the State of Florida between 1994 and 2010. We use unique physician license numbers to link three datasets. For the observations in the hospital data that listed physician UPINs instead of license numbers, we created a crosswalk of UPINs and license numbers using the American Medical Association data.

Hospital Inpatient Data File

The Hospital Inpatient Data File is a dataset containing hospital discharge data for any inpatient hospital stay in the State of Florida available from the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. We restrict our analysis to hospital stays for a birth by relevant diagnosis‐related group (DRG) codes. These data include all hospital births in the State of Florida and contain patient demographics (gender, race, age, insurance), patient medical characteristics (DRG and ICD‐9 codes), hospital stay (reporting year/quarter, length of stay, discharge status), and identification of the associated physician(s). We identify births that were delivered vaginally, by Cesarean, or VBAC, and identify breech, multiple, or premature births.

American Medical Association Physician Masterfile

The American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterfile contains information on physician characteristics, including gender, date of graduation from medical school, and the like. The AMA data are a snapshot of the physician collected at the point of data acquisition by the researcher, not historical or panel data. We obtained these data for Florida physicians based on license numbers and/or UPIN numbers.

Medical Malpractice Claims

The medical malpractice claims data are drawn from the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation (FLOIR). These data are publicly available and contain information on all providers in the State of Florida who have had any malpractice claim since the 1970s. For each malpractice incident reported, data include the occurrence or injury date, initial contact/report date, lawsuit date, final date, the final disposition, any dollar settlements or judgments, and severity of the injury. Incidents are required to be reported to the Office of Insurance Regulation according to Florida Statute 627.912, when “any written claim or action for damages for personal injuries claims to have been caused by error, omission, or negligence in the performance of such insured's professional services or based on a claimed performance of professional services without consent.” A “claim” refers to “the receipt or notice of intent to initiate litigation, a summons or complaint, or a written document from a person or his or her legal representation stating an intention to pursue an action.” The dataset, therefore, is a census of all malpractice incidents where there was initial contact (and therefore a report to FLOIR), and some of those (but not all) resulted in a subsequent filing of a lawsuit (also reported to FLOIR).

Sample

Our sample includes hospital deliveries linked to physician malpractice claim histories between 1994 and 2010. We exclude physicians with malpractice claims before 1994, the first year of our linked hospital discharge data. We model the first time a physician was individually exposed to a malpractice liability claim and observe concurrent and future treatment decisions. Midwives are excluded as they do not perform Cesareans or VBACs. We also restrict the sample (in line with the literature in this area) to include physicians who delivered at least five babies per quarter to focus on physicians who routinely perform deliveries. This sample comprises almost 2 million births delivered by approximately 2,300 physicians. Table 1 depicts summary statistics for primary Cesarean (conditional on no prior Cesarean) and VBAC (conditional on a prior Cesarean), identified by those physicians exposed and never exposed to a malpractice claim during the data period, based on either the first reporting or first lawsuit. Note that not all malpractice reports lead to lawsuits; therefore, fewer patients of physicians exist who ever experienced a first lawsuit. These groups look very similar in observational characteristics, which provide support for our methodology.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics (Means), 1994–2010

| No Malpractice Report | Ever Malpractice Report | No Malpractice Lawsuit | Ever Malpractice Lawsuit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Primary Cesarean Delivery (Conditional on No Prior Cesarean) | ||||

| Variable | (N = 1,590,255) (No. doctors = 1,888) | (N = 726,249) (No. doctors = 450) | (N = 1,754,434) (No. doctors = 1,998) | (N = 562,070) (No. doctors = 340) |

| Primary cesarean | 0.231 | 0.221 | 0.230 | 0.220 |

| Vaginal birth | 0.769 | 0.779 | 0.769 | 0.780 |

| Premature birth | 0.080 | 0.074 | 0.080 | 0.075 |

| Multiple birth | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| Breech | 0.064 | 0.062 | 0.063 | 0.063 |

| Medicaid | 0.460 | 0.408 | 0.460 | 0.393 |

| Old mother (35+) | 0.124 | 0.129 | 0.123 | 0.131 |

| Young mother (<=20) | 0.190 | 0.176 | 0.190 | 0.173 |

| African American | 0.219 | 0.200 | 0.219 | 0.194 |

| Physician years practicing | 19.55 | 16.28 | 19.22 | 16.36 |

| Panel B: VBACs (Conditional on a Prior Cesarean) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | (N = 280,805) (No. doctors = 1,834) | (N = 122,573) (No. doctors = 443) | (N = 309,007) (No. doctors = 1,944) | (N = 93,371) (No. doctors = 333) |

| Repeat Cesarean | 0.864 | 0.868 | 0.865 | 0.864 |

| Vaginal birth after Cesarean | 0.136 | 0.132 | 0.135 | 0.136 |

| Premature birth | 0.075 | 0.067 | 0.074 | 0.067 |

| Multiple birth | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| Breech | 0.063 | 0.057 | 0.062 | 0.057 |

| Medicaid | 0.451 | 0.393 | 0.451 | 0.376 |

| Old mother (35+) | 0.222 | 0.230 | 0.221 | 0.234 |

| Young mother (<=20) | 0.055 | 0.049 | 0.054 | 0.048 |

| African American | 0.220 | 0.207 | 0.221 | 0.200 |

| Physician years practicing | 20.63 | 16.87 | 20.26 | 16.96 |

Notes: Summary statistics (means) are calculated at the patient level for years 1994 through 2010, where Panel A shows summary statistics conditional on no prior Cesarean (i.e., the primary Cesarean sample), and Panel B shows summary statistics conditional on a prior Cesarean (i.e., the VBAC sample). The sample is defined as all physicians delivering babies between 1994 and 2010, excluding those who experienced a malpractice claim prior to 1994, the first year of our linked hospital discharge data. Physicians are restricted to delivering at least five babies per quarter.

Empirical Methodology

We use a fixed effects, difference‐in‐difference approach to consider malpractice liability exposure on physician delivery decisions. Using ordinary least squares (OLS), equation (1) is as follows:

| (1) |

where each observation is a patient‐level record for patient i delivered by doctor j in quarter t; Yijt is an indicator for the procedure of interest (e.g., primary Cesarean delivery, VBAC); FirstExposurejt indicates the first quarter after which physician j was exposed to a malpractice claim and every quarter thereafter (or 0 otherwise); Xijt is a vector of maternal (race, age, and insurance status), infant/birth (premature, multiple birth, breech), and physician (number of years practicing) characteristics; Өj represents physician fixed effects; π t represents quarter‐year fixed effects; and μ ijt is a random error term. Standard errors are clustered at the physician level. This approach requires similar trends between physicians who were ultimately exposed to medical malpractice liability and those who were not. In graphs of “ever exposed” and “never exposed” physicians, we observe that these physicians trend similarly (see Figures S1 and S2 in Appendix SA2).

We are interested in the first time a physician was exposed to a medical malpractice claim. Our identification strategy relies on this first malpractice claim, identifying any effect from within‐physician changes in Cesarean deliveries and VBACs. We consider variations of malpractice liability exposure within FirstExposureijt: the initial contact about the potential lawsuit (reporting date) and filing of a lawsuit (lawsuit date). We exploit the quarter in which the physician was first contacted about a potential lawsuit, and the quarter the incident was filed as a lawsuit (if one was filed), considering each independently to examine the potential effect on delivery decisions. In our sample, the average time between the injury occurrence and the initial report is approximately 5 quarters and between the initial report and the filing of the lawsuit (if one occurred) is approximately 3 quarters. Approximately 90 percent of claims moved from occurrence to report in 10 quarters or less, and 90 percent of claims moved from report to lawsuit (if one occurred) in 8 quarters or less. We also use the severity measure in the FLOIR data to categorize injuries as severe, that is, permanent injuries or death.

The prior literature has measured malpractice liability exposure using all medical malpractice incidents linked to a particular physician. We hand‐coded observations in the FLOIR data to identify obstetrics‐related malpractice using the description and location of the incident that leads to a report. We use this information to categorize malpractice claims as OB‐related (relative to GYN‐related) and Labor and Delivery‐related. Relative to OB‐related malpractice liability, we hypothesize that GYN‐related liability may have a more limited impact (if any) on physician delivery decisions. Of the total malpractice claim observations (measured by first report), approximately 63 percent were OB‐related and 43 percent were Labor/Delivery‐related. This allows us to more specifically focus on those incidents that likely affect a physician's delivery decisions.

Shurtz (2012) presents an analysis using adverse events conditional on subsequent lawsuit (i.e., “medical errors”). The FLOIR requires that any contact about a potential medical malpractice must be reported. This means that we do not observe all “bad occurrences,” but only occurrences with contact about a potential lawsuit. In our analysis, we analyze a different sample and measure of liability than Shurtz (2012). Although we have concerns about the identification and the selected sample resulting from the definition of “medical errors,” we explore utilizing exposure of an adverse event conditional on a later lawsuit in the subsequent analyses for comparison purposes.

Results

Medical Malpractice Exposure in the State of Florida

Using the FLOIR data, we first describe the medical malpractice landscape for OB/GYNs in Florida. Of course, our data and results are specific to the State of Florida, and while most states do not collect data in a form useful for our exercise, we note the limitation of our study to this specific (but large) state.

The vast majority of physicians in our sample had no malpractice liability exposure during the portion of their careers that we observe between 1994 and 2010. For our sample of physicians, approximately 19 percent experienced a report of a malpractice claim, while 15 percent experienced a lawsuit. Of the physicians who experienced a malpractice report, 63 percent had only one report. If we focus on severe reports and severe lawsuits, defined as those incidents where injuries were permanent, we find that 16 percent of our sample of physicians experienced a severe malpractice report, while 13 percent experienced a severe lawsuit.

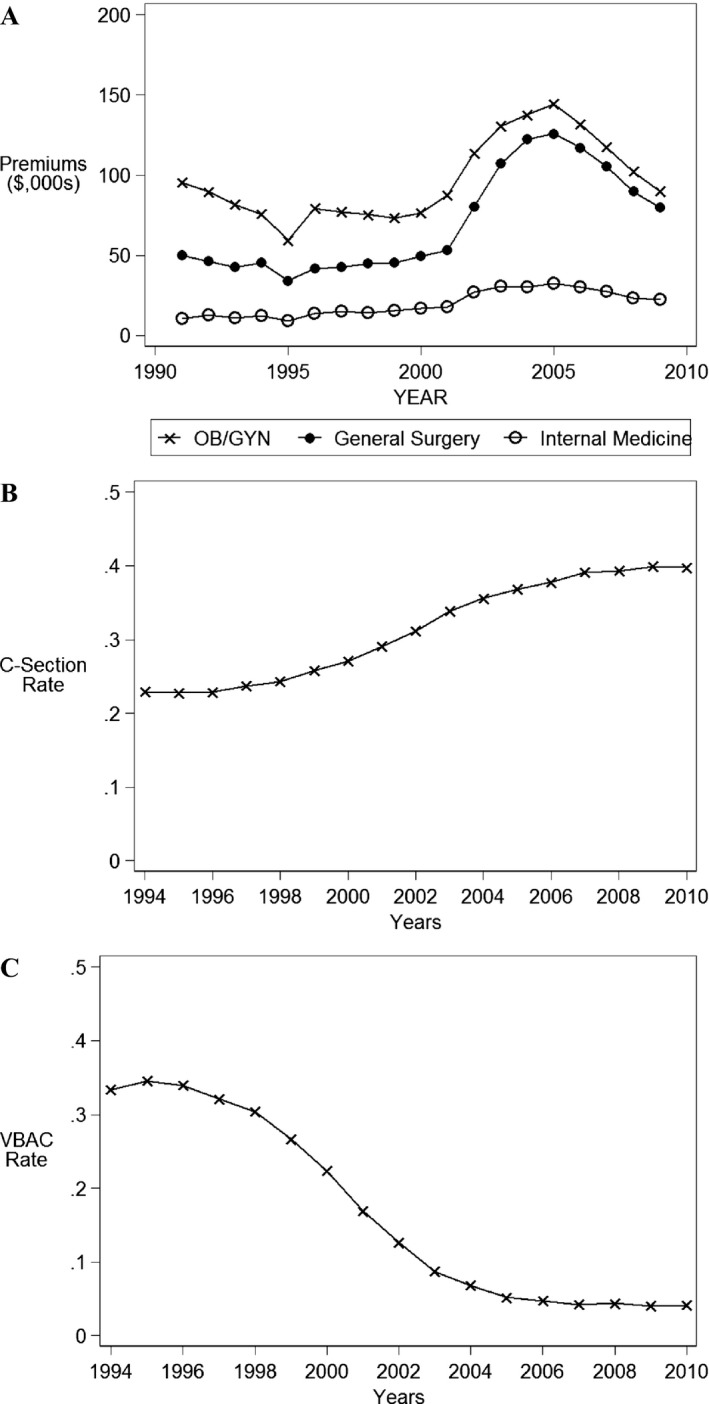

While not all obstetricians in Florida have experienced a malpractice claim, the cost of practicing for these physicians in the State of Florida is considerable. Malpractice insurance is typically not experience‐rated. Figure 1 (A) shows the trends in liability insurance using data from the Medical Liability Monitor for OB/GYNs relative to internal medicine physicians and general surgeons over the 1991 to 2009 time period averaged over the entire state of Florida. Inflation‐adjusted premiums increased for all three physician types in the 2000s but most considerably for OB/GYNs as well as general surgeons.

Figure 1.

- Notes: A: Medical Liability Premiums, Medical Liability Monitor (MLM), relevant years, inflation‐adjusted 1991 dollars. B: Rate of deliveries performed by Cesarean, Florida hospital discharge data, relevant years. C: Rate of deliveries performed by VBAC, conditional on prior Cesarean, Florida hospital discharge data, relevant years.

Descriptive Data

Our data suggest that there has been a rapid increase in Cesarean deliveries as depicted in Figure 1 (B). From 1994 to 2010, Cesarean delivery increased substantially from approximately 25 percent of births to almost 40 percent of births. Figure 1 (C) shows that VBACs, conditional on having a prior Cesarean, dropped from roughly 30 percent to 4 percent in 2010. The VBAC rate is not only a function of the proportion of births where a Cesarean was the prior delivery method but also the decreased likelihood to perform a VBAC among this subgroup of births.

Empirical Findings

Table 2 (Panel A) presents the results of our estimation of equation (1) for primary Cesareans (columns 1–3) and VBACs (columns 4–6). The results in Panel A show no statistically significant change in the likelihood of a primary Cesarean overall, either resulting from the first report, severe (i.e., permanent injury/death) report, or lawsuit. Severe (or permanent) incidents may be ones where the physician is aware that a bad outcome occurred and those that may be more likely to lead to the filing of a lawsuit. In fact, severe occurrences may be more meaningful in a labor and delivery context than in a general OB/GYN context because severe occurrences are often observed at the time of delivery (i.e., injury or death of a baby).

Table 2.

Effect of Medical Malpractice Liability Exposure on Cesarean and Vaginal Births after Cesarean (VBACs)

| Specification | Primary Cesarean | VBAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Panel A: Effect of Malpractice Liability Exposure | ||||||

| First report | −0.0057 | −0.0145** | ||||

| (0.0041) | (0.0062) | |||||

| First severe report | −0.0055 | −0.0124* | ||||

| (0.0048) | (0.0069) | |||||

| First lawsuit | −0.0042 | −0.0189*** | ||||

| (0.0044) | (0.0069) | |||||

| Panel B: Effect of OB‐Related Malpractice Liability Exposure | ||||||

| First report | −0.0028 | −0.0159** | ||||

| (0.0050) | (0.0071) | |||||

| First severe report | −0.0002 | −0.0117 | ||||

| (0.0057) | (0.0077) | |||||

| First lawsuit | −0.0007 | −0.0224*** | ||||

| (0.0054) | (0.0080) | |||||

| Panel C: Effect of Labor and Delivery‐Related Malpractice Liability Exposure | ||||||

| First report | −0.0032 | −0.0102 | ||||

| (0.0061) | (0.0084) | |||||

| First severe report | −0.0005 | −0.0087 | ||||

| (0.0068) | (0.0093) | |||||

| First lawsuit | −0.0031 | −0.0148 | ||||

| (0.0063) | (0.0093) | |||||

| N (patient obs.) | 2,316,504 | 403,378 | ||||

| No. doctors | 2,338 | 2,277 | ||||

| Mean outcome | 0.228 | 0.135 | ||||

Notes: Sample is all physicians delivering babies between 1994 and 2010, excluding those who experienced a malpractice claim prior to 1994, the first year of our linked hospital discharge data. Primary Cesarean is conditional on no prior Cesarean, while VBAC is conditional on a prior Cesarean. These regressions control for the following covariates: premature birth, multiple birth, breech birth, African American, young mom (<20), old mom (>35), Medicaid, number of years doctor has been practicing, doctor, and quarter‐year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the doctor level. Observations are included if the infant was delivered by a physician who delivered at least five babies per quarter.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

We then condition on prior Cesarean and estimate equation (1) for VBACs. Note that the number of observations (both patient level and physician level) in the primary Cesarean models is different from the VBAC models as the likelihood of a VBAC is conditional on having had a prior birth, where that prior birth was delivered via Cesarean. The coefficients with respect to VBACs show statistically significant, negative effects of malpractice liability exposure (either report, severe report, or lawsuit) on the likelihood of a VBAC. These coefficients reflect a 1.2–1.9 percentage point reduction in the likelihood of a VBAC delivery (or 1.2–1.9 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a repeat Cesarean). Relative to the mean incidence of VBACs during the data period (mean = 0.135), this amounts to roughly a 10 percent reduction in the likelihood of a VBAC delivery for this subgroup of births. This is the direct effect resulting from the individual physician's malpractice liability experience; other factors, such as the malpractice experience of one's peers, could modify this effect. Unfortunately, we are unable to consider this relationship because we cannot identify physician practice relationships over time. We also estimated equation (1) using county and hospital fixed effects, respectively, as well as standard errors clustered at the hospital level and doctor/hospital level (Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller 2011), and the results (available by request) are qualitatively similar.

If some observed malpractice liability exposure is unrelated to a physician's delivery decisions, then including those incidents within our first liability exposure measures may lead to biased effects. As such, we estimate equation (1) limiting malpractice liability exposure to OB‐related and Labor/Delivery‐related claims. Our results in Table 2 (Panel B) continue to support the original findings in Panel A that physician malpractice liability exposure does not appear to be related to primary Cesarean but is negatively related to the likelihood of a VBAC (and therefore positively related to the likelihood of a repeat Cesarean delivery). Specifically, the effect of OB‐related malpractice liability (Panel B) on the likelihood of a VBAC delivery ranged from a reduction of 1.6 to 2.2 percentage points. Relative to the mean incidence, these effects are larger (roughly a 15 percent reduction in the likelihood of a VBAC) than in Panel A. For Labor/Delivery‐related liability exposure (Panel C), the coefficients are similar in magnitude to Panel B, but we lose precision. This may be in part due to a lack of statistical power given the fewer number of physicians exposed to Labor/Delivery‐related malpractice liability (43 percent of malpractice liability was Labor/Delivery‐related).

The “medical malpractice crisis” began in the early 2000s and the decline in VBACs also began around that time. As such, there is reason to suspect that the potential response to malpractice in the 1990s may be different from the 2000s. To consider whether the timing of the first malpractice claim affected the likelihood of VBACs differentially between these two periods, we consider an alternative to equation (1). For our measures of liability, first report (Panel A), first severe report (Panel B), and first lawsuit (Panel C), we separate these into those that happened first in the 1990s versus those that happened first in the 2000s. The results of this exercise are presented in Table 3 for primary Cesareans and VBACs for all, OB‐related, and Labor/Delivery‐related malpractice liability exposure. Each block represents a separate regression, where the cell contains two measures, one for the 1990s and one for the 2000s. Again, we observe no statistically significant relationship between malpractice liability exposure and primary Cesarean. The results are suggestive that most of the negative effect on VBACs is coming from malpractice liability exposure in the 1990s (although t‐tests indicate that the 1990s coefficients are not statistically different from the 2000s coefficients). In particular, we see larger coefficients (e.g., 4.3–6.1 percentage point reductions from 1990s reports). Additionally, the coefficients are larger as the malpractice liability exposure is more narrowly specified (i.e., moving from All to OB‐related to Labor/Delivery‐related). Relative to the mean VBAC incidence during the 1990s (approximately 30 percent), these effects amount to between a 14 to 20 percent decline in the likelihood of a VBAC delivery. We note that in Panel C, we find statistically significant effects of first lawsuit in the 2000s, but the coefficients in the 1990s continue to support the same qualitative story (although not statistically significant in every model) that the response to malpractice liability is to reduce VBAC delivery. These findings may be due to the relatively high VBAC rate in the 1990s versus the 2000s and the subsequent malpractice crisis that occurred in the 2000s. Given the relatively low VBAC rate that has persisted through most of the 2000s, it may be that subsequent malpractice liability exposure occurring in the later period simply cannot reduce VBAC incidence much further.

Table 3.

Effect of Malpractice Liability Exposure on Cesarean and Vaginal Births after Cesarean (VBAC): the 1990s vs. the 2000s

| Specification | Primary Cesarean | VBAC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | OB Only | Labor/Delivery Only | All | OB Only | Labor/Delivery Only | |

| Panel A: First Report | ||||||

| First report 90s | −0.0039 | −0.0042 | −0.0029 | −0.0425** | −0.0466** | −0.0608*** |

| (0.0066) | (0.0082) | (0.0093) | (0.0172) | (0.0206) | (0.0233) | |

| First report 00s | −0.0059 | −0.0025 | −0.0032 | −0.0106* | −0.0116 | −0.0018 |

| (0.0045) | (0.0056) | (0.0069) | (0.0064) | (0.0073) | (0.0084) | |

| Panel B: First Severe Report | ||||||

| First severe report 90s | −0.0008 | −0.0019 | −0.0032 | −0.0446** | −0.0455** | −0.0643** |

| (0.0076) | (0.0088) | (0.0101) | (0.0211) | (0.0228) | (0.0253) | |

| First severe report 00s | −0.0063 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | −0.0079 | −0.0068 | 0.0012 |

| (0.0053) | (0.0064) | (0.0079) | (0.0071) | (0.0079) | (0.0092) | |

| Panel C: First Lawsuit | ||||||

| First lawsuit 90s | 0.0042 | 0.0085 | 0.0069 | −0.0301 | −0.0266 | −0.0483* |

| (0.0069) | (0.0083) | (0.0101) | (0.0214) | (0.0237) | (0.0285) | |

| First lawsuit 00s | −0.0052 | −0.0017 | −0.0043 | −0.0176** | −0.0219*** | −0.0111 |

| (0.0048) | (0.0058) | (0.0069) | (0.0072) | (0.0084) | (0.0097) | |

| N (patient obs.) | 2,316,504 | 403,378 | ||||

| No. doctors | 2,338 | 2,277 | ||||

| Mean outcome | 0.228 | 0.135 | ||||

Notes: Sample is all physicians delivering babies between 1994 and 2010, excluding those who experienced a malpractice claim prior to 1994, the first year of our linked hospital discharge data. Primary Cesarean is conditional on no prior Cesarean, while VBAC is conditional on a prior Cesarean. These regressions control for the following covariates: premature birth, multiple birth, previous Cesarean, breech birth, African American, young mom (<20), old mom (>35), Medicaid, number of years doctor has been practicing, doctor, and quarter‐year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the doctor level. Observations are included if the infant was delivered by a physician who delivered at least five babies per quarter.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

Finally, in Table 4, we estimate equation (1) by considering malpractice occurrences, conditional on a lawsuit being filed. This is similar to the effect considered in Shurtz (2012), who defines “medical errors” as adverse events that lead to lawsuits. We do not believe that occurrence date is the appropriate claim event because the sample of occurrences in the data are only those that lead to malpractice reports and were therefore mandated to be reported to FLOIR. In other words, what Shurtz (2012) terms “medical errors” is a subset of “bad occurrences.” Regardless, we test equation (1) on the sample of physicians used in Table 2, for occurrences that lead to lawsuits, using our identification strategy and our data. We emphasize that Shurtz (2012) uses a different constructed sample and identification strategy. Additionally, we have also estimated the effect of first report conditional on a subsequent lawsuit, which is more similar to Table 2. These results are presented in Table 4 and continue to support our original findings. Occurrences conditional on a lawsuit have no identifiable effect on primary Cesareans (in contrast to Shurtz 2012), but we again find negative, statistically significant results with respect to VBACs (1.7–1.9 percentage points).

Table 4.

Effect of “Medical Errors” (i.e., Occurrences That Lead to Lawsuits) on Cesarean and Vaginal Births after Cesarean (VBAC)

| Specification | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cesarean | VBAC | |||

| First occurrence conditional on a lawsuit | −0.0104** | −0.0167** | ||

| (0.0045) | (0.0080) | |||

| First report conditional on a lawsuit | −0.0053 | −0.0193*** | ||

| (0.0046) | (0.0072) | |||

| N (patient obs.) | 2,316,504 | 403,378 | ||

| No. doctors | 2,338 | 2,277 | ||

| Mean outcome | 0.228 | 0.135 | ||

Notes: Sample is all physicians delivering babies between 1994 and 2010, excluding those who experienced a malpractice claim prior to 1994, the first year of our linked hospital discharge data. These regressions control for the following covariates: premature birth, multiple birth, previous Cesarean, breech birth, previous Cesarean, African American, young mom (<20), old mom (>35), Medicaid, number of years doctor has been practicing, doctor, and quarter‐year fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the doctor level. Observations are included if the infant was delivered by a physician who delivered at least five babies per quarter.

*p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

As a last check, we consider the possibility that physicians alter their patient mix in response to malpractice liability exposure. We test the effect of the first malpractice claim on patient‐level observable characteristics. These results (available by request) suggest that there is very little evidence that physicians’ patient mix responds to the first malpractice claim.

Discussion

The large rise in Cesareans and decrease in VBACs, coupled with the associated rise in health care costs for labor and delivery, has prompted inquiries into possible causes. In this study, we investigate the role of physician‐level malpractice liability exposure, measured at several points throughout the trajectory of a malpractice claim, including the initial report about a potential lawsuit and filing of a lawsuit. Using data from the State of Florida, we identify physician delivery decisions based on primary Cesareans and VBAC conditional on a prior Cesarean. We consistently find no evidence that malpractice liability exposure is associated with primary Cesareans. We find, however, that malpractice liability exposure affects physician decisions for births where there was a prior Cesarean, decreasing the likelihood of a VBAC, and thereby increasing the likelihood of a Cesarean for women with a prior Cesarean. Our results suggest that individual malpractice liability exposure results in at least a 10 percent reduction in the likelihood of a VBAC. This finding appears to be concentrated among claims that occurred in the 1990s (versus the 2000s), a time when the VBAC rate was relatively high. Similar results are found when we consider severe malpractice claims, obstetric‐related or labor/delivery‐related claims, and adverse events that lead to lawsuits.

This study is set in the State of Florida, which has unique data available making the linkage of hospital discharge and physician malpractice liability data possible. Florida, however, is one of eight states with an unlimited homestead exemption, meaning that a physician could declare bankruptcy if threatened with a large damage award, effectively protecting the physician's assets invested in the home. Additionally, Florida law requires physicians with hospital privileges to hold malpractice insurance (or a line of credit if they forgo insurance coverage and go “bare”) of $250,000 per incident and $750,000 annually (Florida Statute 458.320). Based on our data, however, the number of large awards is actually quite low (95 percent of awards in our data are less than $500,000; 88 percent of awards in our data are less than $250,000) and unlikely to affect our results. We acknowledge this limitation that makes Florida somewhat different from other states if the insurance coverage that physicians select is lower than in other states or if plaintiffs’ attorneys are less likely to take a case when faced with a “bare” physician (see, e.g., Baker, Helland, and Klick 2016). While our results may be most generalizable to those states with unlimited homestead exemptions, findings from Florida provide important evidence from the fourth largest state (like Texas, another large state with an unlimited homestead exemption). Future research could further investigate the effects of malpractice liability exposure in states with different legal environments.

Our findings indicate that while there appears to be a physician response to malpractice liability exposure through reductions in VBAC deliveries (and increased Cesarean deliveries among prior Cesarean births), there must be other primary causes driving the large increases in Cesareans overall. Physician‐level malpractice liability exposure is only in part responsible for the sizeable drop in VBACs and increase in repeat Cesareans the United States has experienced between 1994 and 2010. Other possible reasons (not tested in this study) include hospital or insurer restrictions over TOLAC and/or VBAC, physician practice or preferences, or patient preferences. Given the large reduction in the incidence of VBACs over our sample period and the rise in Cesarean delivery (both primary and repeat), the implications are policy‐relevant. ACOG has issued revised guidelines recommending a trial of labor after Cesarean (TOLAC) and VBAC for many low‐risk women with a prior Cesarean delivery. Based on these recommendations, changes in physician practice could alter the trend in TOLAC/VBAC. A reversal of the VBAC trend could decrease the Cesarean delivery rate (in part), lower health care costs, and reduce medical complications for this subgroup of births.

Supporting information

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2:

Figure S1: Probability of a Cesarean Delivery by Physician Malpractice Liability Status (Ever versus Never Malpractice Report).

Figure S2: Probability of a VBAC Delivery by Physician Malpractice Liability Status (Ever versus Never Malpractice Report).

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: We did not receive any external funding for this project. We were supported through our employment at our respective universities, UNC‐Chapel Hill and University of Kentucky.

Disclosure: None.

Disclaimer: None.

Note

There are approximately 4 million births in the United States each year. The 12 percentage point increase in the Cesarean rate suggests an extra 480,000 Cesareans each year with a marginal cost (relative to a vaginal delivery) of roughly $6,000 or a total of $2.88 billion per year. This estimate is the direct cost (solely higher delivery cost) of increased Cesareans; the total cost of increased Cesareans (complications, recovery time, etc.) is likely higher.

References

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG ). 2010. “Vaginal Birth after Previous Cesarean Delivery.” Practice Bulletin 115: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- AMA Physician Masterfile [accessed on February 25, 2013]. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/physician-data-resources/physician-masterfile.page

- Baker, T. , Helland E., and Klick J.. 2016. “Everything's Bigger in Texas: Except the Medmal Settlements.” Connecticut Insurance Law Journal 22: 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. C. , Gelbach J. B., and Miller D. L.. 2011. “Robust Inference with Multiway Clustering.” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 29 (2): 238–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dranove, D. , and Watanabe Y.. 2010. “Influence and Deterrence: How Obstetricians Respond to Litigation against Themselves and Their Colleagues.” American Law and Economics Review 12 (1): 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ebell, Mark. H. 2007. “Predicting the Likelihood of Successful Vaginal Birth after Cesarean.” American Family Physician 76 (8): 1992–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, 1994–2010. Available at http://www.floridahealthfinder.gov/researchers/orderdata/order-data.aspx

- Florida Office of Insurance Regulation. Available at https://apps.fldfs.com/PLCR/Search/MPLClaim.aspx

- Gimm, G. 2010. “The Impact of Malpractice Liability Claims on Obstetrical Practice Patterns.” Health Services Research 45 (1): 195–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, D. , and McInnes M. M.. 2004. “Malpractice Experience and the Incidence of Cesarean Delivery: A Physician‐Level Longitudinal Analysis.” Inquiry 41 (2): 170–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grobman, W. A. , Lai Y., Landon M. B., Spong C. Y., Rouse D. J., Varner M. W., Caritis S. N., Harper M., Wapner R. J., and Sorokin Y.. 2011. “The Change in the Rate of Vaginal Birth after Caesarean Section.” Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 25 (1): 37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCUP . 2009. Statistics on Hospital Stays. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, B. D. , Todd J. K., Glazner J. E., Lezotte D., and Lynch A. M.. 2009. “Neonatal Outcomes after Cesarean Delivery.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 113 (6): 1231–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon‐Rochelle, M. , Holt V. L., Easterling T. R., and Martin D. P.. 2001. “Risk of Uterine Rupture during Labor among Women with a Prior Cesarean Delivery.” New England Journal of Medicine 345: 3–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. A. , Hamilton B. E., Osterman M. J., Curtin S. C., and Mathews T. J.. 2013. “Births: Final Data for 2012.” National Vital Statistics Report 62 (9): 1–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, J. , and Simon K.. 2009. “Patient Education and the Impact of New Medical Research.” Journal of Health Economics 28: 1166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shurtz, I. 2012. “The Impact of Medical Errors on Physician Behavior: Evidence from Malpractice Litigation.” Journal of Health Economics 32: 331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. T. , Mello M. M., Subramanian S., and Studdert D. M.. 2009. “Relationship between Malpractice Litigation Pressure and Rates of Cesarean Section and Vaginal Birth after Cesarean Section.” Medical Care 47 (2): 234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2:

Figure S1: Probability of a Cesarean Delivery by Physician Malpractice Liability Status (Ever versus Never Malpractice Report).

Figure S2: Probability of a VBAC Delivery by Physician Malpractice Liability Status (Ever versus Never Malpractice Report).