Abstract

The tobacco-derived nitrosamines 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) are known human carcinogens. Following metabolic activation, NNK and NNN can induce a number of DNA lesions, including several 4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl (POB) adducts. However, it remains unclear to what extent these lesions affect the efficiency and accuracy of DNA replication and how their replicative bypass is influenced by translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases. In this study, we investigated the effects of three stable POB DNA adducts (O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG) on the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication in HEK293T human cells. We found that, when situated in a double-stranded plasmid, O2-POB-dT and O4-POB-dT moderately blocked DNA replication and induced exclusively T→A (∼14.9%) and T→C (∼35.2%) mutations, respectively. On the other hand, O6-POB-dG slightly impeded DNA replication, and this lesion elicited primarily the G→A transition (∼75%) together with a low frequency of the G→T transversion (∼3%). By conducting replication studies in isogenic cells in which specific TLS DNA polymerases (Pols) were deleted by CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, we observed that multiple TLS Pols, especially Pol η and Pol ζ, are involved in bypassing these lesions. Our findings reveal the cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of specific POB DNA adducts and unravel the roles of several TLS polymerases in the replicative bypass of these adducts in human cells. Together, these results provide important new knowledge about the biological consequences of POB adducts.

Keywords: DNA damage, DNA replication, DNA polymerase, mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, DNA adduct, DNA alkylation, N-nitrosamine, translesion synthesis, translesion synthesis polymerase

Introduction

Tobacco smoking leads to more than 30% of all cancer deaths in developed countries, and ∼90% of male lung cancer deaths and 75–80% of female lung cancer deaths in the United States can be attributed to tobacco smoking (1, 2). Tobacco and its smoke contain more than 70 carcinogens; among them, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK)2 and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) were shown to induce cancer in rodents and are among the most potent tobacco-derived human carcinogens (3). The carcinogenic effects of NNN and NNK are thought to be attributed to their metabolic activation, the subsequent formation of DNA adducts, and the ensuing induction of mutations during DNA replication (4).

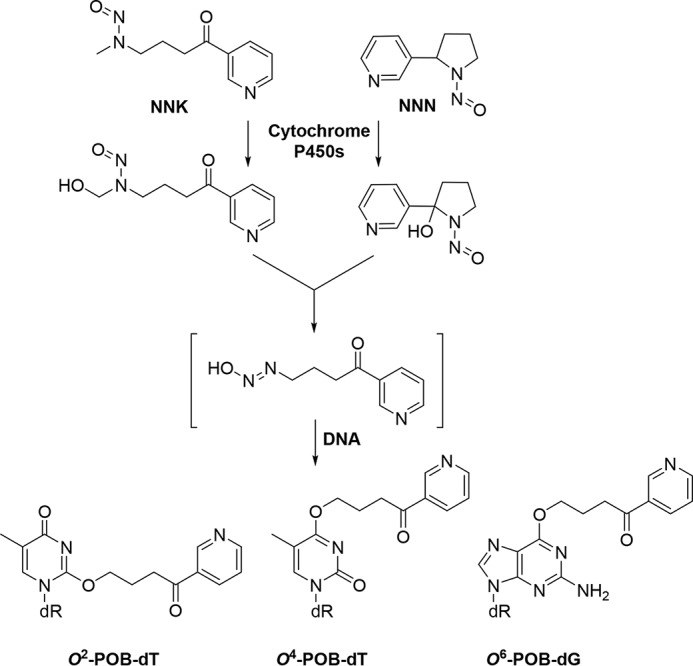

Both NNK and NNN can be metabolically activated by the cytochrome P450 family of enzymes, and the resulting metabolites can subsequently react with DNA to yield 4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutyl (POB) adducts along with other DNA lesions (Fig. 1) (5, 6). Four POB adducts, including O2-POB-dT, O2-POB-cytosine, O6-POB-dG, and N7-POB-guanine, were found to accumulate at significant levels in DNA of lung tissues of NNK-treated rats (7). Three of these adducts (O2-POB-dT, O6-POB-dG, and N7-POB-guanine) were detected in A/J mice upon exposure to another pyridyloxobutylating agent, 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNKOAc) (8, 9). In addition, it was found that exposure of cultured mammalian cells to NNKOAc could lead to the formation of appreciable levels of O4-POB-dT, along with the abovementioned O2-POB-dT and O6-POB-dG (10). Several replication studies have been carried out for POB DNA adducts. In this vein, O2-POB-dT is highly blocking and miscoding during DNA replication in both Escherichia coli and mammalian cells (6, 11). Likewise, O6-POB-dG is highly mutagenic, and it induces exclusively G→A transition in E. coli and both G→A and G→T mutations in cultured human cells (12, 13). The cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of O4-POB-dT, however, have not yet been examined.

Figure 1.

Metabolic activation of NNK/NNN and the ensuing formation of O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG.

The replicative DNA polymerases in eukaryotes (i.e. Pol δ and ϵ), despite being highly efficient and accurate in normal DNA replication, are unable to replicate across many damaged nucleosides in template DNA (14, 15). To maintain genomic stability, cells are equipped with specialized translesion synthesis (TLS) DNA polymerases to bypass unrepaired DNA lesions. The Y family polymerases Pol η, ι, and κ and the B family polymerase Pol ζ, which interact with another Y family polymerase, REV1, assume major roles in translesion synthesis (16, 17). Weerasooriya et al. (6) found that both the bypass efficiency and the mutagenicity of O2-POB-dT in HEK293T cells were significantly attenuated upon siRNA-mediated knockdown of Pol η or Pol ζ, suggesting the involvement of these TLS polymerases in the mutagenic bypass of O2-POB-dT. It remains unclear how other POB lesions impede DNA replication and how their replicative bypass is influenced by TLS polymerases.

In this study, we constructed double-stranded plasmids containing site-specifically inserted O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG lesions (Fig. 1) and investigated how these lesions impair the efficiency and accuracy of DNA replication in HEK293T cells. We also examined the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies (MFs) of the three lesions in TLS polymerase-deficient cells.

Results

The effects of O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG on the efficiency of DNA replication and the roles of TLS polymerases in bypassing these lesions

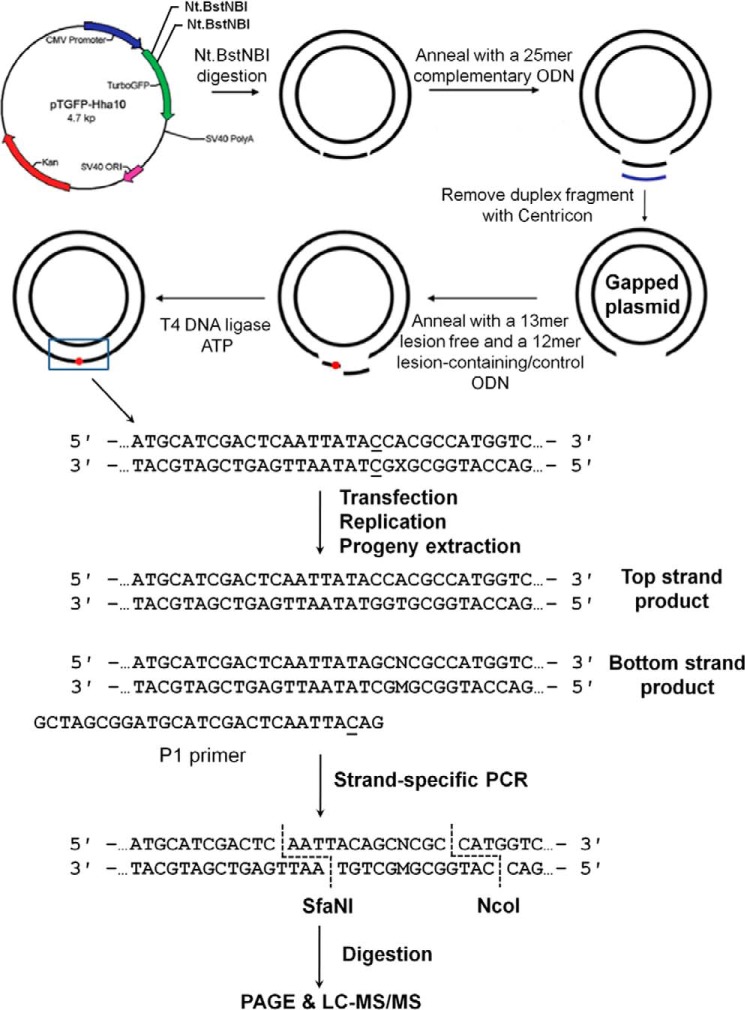

The main objective of this study was to assess how the three major stable POB adducts formed on nucleobases of DNA perturb the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication in human cells and to reveal the identities of translesion synthesis DNA polymerases in bypassing these DNA lesions. We employed a previously described strand-specific PCR-competitive replication and adduct bypass (SSPCR-CRAB) assay for cellular replication experiments. The method involves the construction of a double-stranded plasmid carrying a single structurally defined lesion at a specific site, co-replication of the damage-containing plasmid with a damage-free competitor plasmid in cultured human cells, isolation of the progeny genomes, selective PCR amplification of the replication products of the strand initially carrying the lesion, restriction digestion of the PCR products, and identification/quantification of restriction fragments harboring the initial damage site using native PAGE and LC-MS/MS analysis (Figs. 2 and 3) (18). In particular, we first synthesized oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODNs) harboring a site-specifically incorporated O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG (The electrospray ionization-MS and MS/MS for these three lesion-containing ODNs are shown in Figs. S1–S3). We subsequently utilized a previously established protocol to produce double-stranded, lesion-housing plasmids as well as the corresponding control (dT or dG) plasmids (Fig. 2) (18). We also constructed a competitor vector that contained three additional nucleotides in the region between the two restriction cleavage sites and served as an internal reference for gauging the extent to which the DNA lesion impeded DNA replication. The competitor vector was co-transfected at fixed molar ratios with the lesion-harboring or control plasmids into HEK293T cells or isogenic cells, with Pol η, Pol ι, Pol κ, Pol ζ, or both Pol η and Pol ζ being depleted by the CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing method (Fig. S4 shows the sequencing results for confirming the dual knockout of Pol η and Pol ζ). At 24 h following transfection, the progeny genomes were isolated, followed by DpnI and exonuclease III digestion to eliminate the residual unreplicated plasmids.

Figure 2.

The procedures for construction of the lesion-containing plasmid and the SSPCR-CRAB assay. The original pTGFP-Hha10 vector was digested by Nt.BstNBI, and the resulting gapped plasmid was purified. The lesion-carrying plasmids were subsequently generated by ligating lesion-containing ODN into the gapped plasmid with T4 DNA ligase. X indicates the location of the POB-dT lesions or the corresponding dT (or the O6-POB-dG and the corresponding dG). P1 represents the forward PCR primer that contains a G as the terminal 3′ nucleotide corresponding to the C/C mismatch site of the lesion-bearing genome. A C/A mismatch (underlined) was also introduced 2 nt away from its 3′ end to improve the PCR specificity. M designates the nucleotide incorporated at the lesion site during DNA replication, and N denotes the paired nucleotide of M in the complementary strand. The PCR amplicon was digested and post-labeled, and the restriction fragments were analyzed using native PAGE and LC/MS-MS.

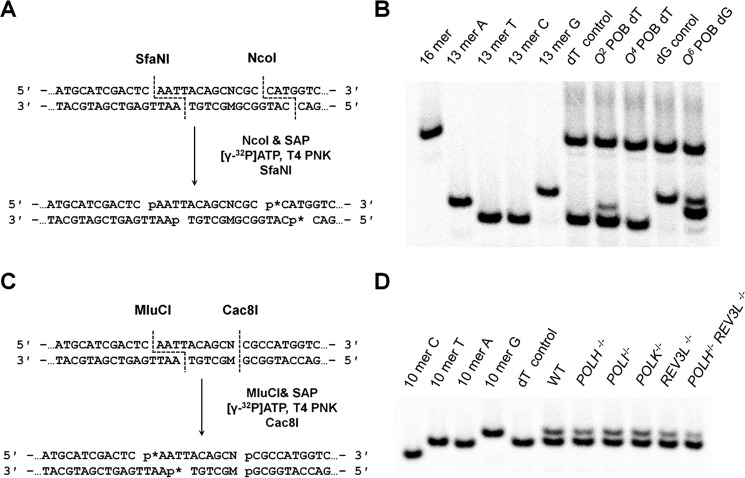

Figure 3.

Restriction digestion and post-labeling method for determining the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies of the lesions in HEK293T cells and the isogenic TLS polymerase-deficient cells. A, restriction digestion of PCR products using NcoI and SfaNI and the post-labeling assay. B, representative gel image showing the NcoI/SfaNI-produced restriction fragments of interest. The standard synthetic ODN representing the restriction fragment arising from the competitor vector (i.e. 5′-CATGGCGATATGCTGT-3′) is designated as 16-mer. 13-mer A, 13-mer G, 13-mer T, and 13-mer C represent the standard synthetic ODNs 5′-CATGGCGMGCTGT-3′, where M is A, G, T, and C, respectively. C, sample processing for restriction cleavage using MluCI and Cac8I and the post-labeling assay. D, representative gel image showing the MluCI/Cac8I-generated restriction fragments of PCR products amplified from the progenies of the O4-POB-dT-containing plasmid arising from replication in HEK293T cells (WT) and the isogenic polymerase-deficient cells (the five lanes on the right). 10-mer A, 10-mer G, 10-mer T, and 10-mer C designate the standard synthetic ODN 5′-AATTACAGCN-3′, where N is A, G, T, and C, respectively. p* indicates a 32P-labeled phosphate group.

The progeny was subsequently amplified by SSPCR using a pair of primers spanning the site where the lesion was originally located. The forward P1 primer contains a G as the terminal 3′ nucleotide corresponding to the C/C mismatch locus (Fig. 2), which facilitates the selective amplification of the progeny genomes from the replication of the lesion-containing strand. Furthermore, a C/A mismatch was incorporated at three nucleotides from its 3′ terminus in the P1 primer to enhance the specificity of SSPCR, as noted previously (Fig. 2) (19). The final PCR amplicon (520 bp) was digested with NcoI/SfaNI or MluCI/Cac8I (Fig. 3, A and C). The restriction fragments were subsequently analyzed using native PAGE (Fig. 3, B and D, and Figs. S5 and S6) and LC-MS/MS to identify the mutagenic products induced from the cellular replication of the POB lesions (Figs. S7–S9; see details under “Experimental procedures”). The quantification data from native PAGE analyses were then employed for calculating the values of relative bypass efficiency (RBE) and MF.

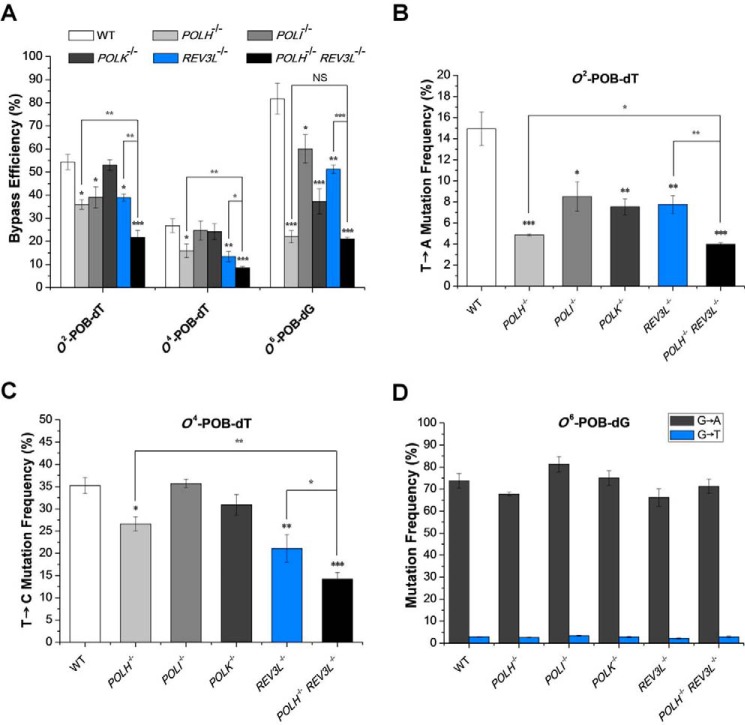

Our PAGE analysis results revealed that O2-POB-dT significantly blocked DNA replication in HEK293T cells, with the RBE value being ∼54% (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Deletion of Pol κ did not exert any pronounced effect on the bypass efficiency of the lesion. In contrast, the bypass efficiencies decreased by 66–72% in cells deficient in Pol η, Pol ι, or Pol ζ (Fig. 4A and Table S1), suggesting the involvement of multiple TLS polymerases in bypassing this lesion.

Figure 4.

A–D, the bypass efficiencies (A) and mutation frequencies of O2-POB-dT (B), O6-POB-dG (C), and O4-POB-dT (D) in HEK293T cells and isogenic TLS polymerase-deficient cells. The bypass efficiencies and the mutation frequencies were calculated from PAGE analyses. The data represent the means and standard deviations of results from three independent replication experiments: *, 0.01 < p < 0.05; **, 0.001 < p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. NS, not significant. The p values were calculated by using unpaired two-tailed Student's t test.

The bypass efficiency of O4-POB-dT (26.7%) was the lowest among the three lesions in HEK293T cells (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Individual knockouts of Pol η or Pol ζ led to diminished bypass efficiencies of the lesion (to ∼16% and 13%, respectively; Fig. 4A and Table S1), although depletion of Pol κ or Pol ι did not appreciably alter the bypass efficiency of the lesion. This result underscored the roles of Pol η and Pol ζ in bypassing the O4-POB-dT lesion in human cells, which is in keeping with what were observed previously for other O4-alkyl-dT lesions (19).

Different from O2- and O4-POB-dT, O6-POB-dG only slightly blocked DNA replication in HEK293T cells, with the bypass efficiency being ∼82% (Fig. 4A and Table S1). However, the bypass efficiencies for O6-POB-dG were significantly decreased in cells lacking any of the four TLS polymerases, where the bypass efficiencies were ∼22%, 60%, 37%, and 51% in cells deficient in Pol η, Pol κ, Pol ι, and Pol ζ, respectively (Fig. 4A and Table S1).

Because both Pol η and Pol ζ are involved in bypassing all three POB lesions, we knocked out both polymerases in HEK293T cells with the CRISPR-Cas9 method (Fig. S4) and conducted replication experiments for the three aforementioned lesions in these cells. Our results showed that both O2-POB-dT and O4-POB-dT displayed lower bypass efficiencies in the double knockout cells than in the isogenic cells depleted of Pol η or Pol ζ alone (Fig. 4A and Table S1). However, further deletion of Pol ζ in the Pol η-deficient background did not further reduce the bypass efficiency of O6-POB-dG, supporting a key role of Pol η in bypassing this lesion (Fig. 4A and Table S1).

The roles of TLS polymerases in modulating the mutagenicity of O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG

We next employed a combination of LC-MS/MS with PAGE analyses to assess the mutagenic properties of the three POB adducts. Our data showed that O2-POB-dT was moderately mutagenic in HEK293T cells, and it gave rise to T→A transversion at a frequency of 14.9% (Fig. 4B and Table S2). Furthermore, significant diminutions in mutation frequencies were observed in the isogenic background with the depletion of each of the four TLS polymerases (Fig. 4B and Table S2), indicating the involvement of multiple polymerases in the mutagenic bypass of the lesion.

O4-POB-dT induces exclusively T→C transition mutation at a frequency of ∼35.2% in HEK293T cells (Figs. 3, B and D, and 4C and Table S2). Although deletion of Pol κ or Pol ι did not lead to any apparent alteration in mutation frequency for the lesion, depletion of Pol η or Pol ζ conveyed significant decreases in the frequencies of T→C mutations to ∼26.6% and ∼21.1%, respectively (Fig. 4C and Table S2). A further drop in mutation frequency was observed in Pol η/Pol ζ-double knockout cells (to ∼14.2%; Fig. 4C and Table S2). These findings are in agreement with the above results of bypass efficiencies and demonstrate that, among the four TLS polymerases studied, only Pol η and Pol ζ are involved in the replicative bypass of the O4-POB-dT lesion.

O6-POB-dG is strongly miscoding, and it induces mainly G→A transition (73.8%), which is accompanied by a low frequency (2.9%) of G→T transversion (Fig. 4D and Table S2). In addition, the mutagenic properties of the lesion were not significantly altered upon depletion of Pol η, Pol κ, Pol ι, or Pol ζ alone or Pol η and Pol ζ in combination (Fig. 4D and Table S2).

Discussion

Tobacco and its smoke contain at least 70 known carcinogens, and tobacco smoking increases the risk of many types of human cancer (3). After metabolic activation, the tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines NNK and NNN, which are classified as group I carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, can result in the formation of a variety of POB DNA adducts (Fig. 1) (2). Understanding the cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of DNA adducts induced by tobacco-specific carcinogens may help the fight against smoking-related diseases.

It was found previously that the minor groove O2-POB-dT adduct is poorly repaired and moderately mutagenic (6, 20, 21), whereas the major groove O6-POB-dG lesion induced substantial frequencies of G→A mutations in mammalian cells (12, 22). In addition, replication studies in cultured human cells with individual TLS polymerases being knocked down with siRNA revealed the involvement of Pol η and Pol ζ in bypassing the O2-POB-dT lesion (6). Although the siRNA approach can efficiently deplete TLS polymerases, incomplete depletion of a polymerase sometimes renders it difficult to clearly define the role of polymerase in modulating the efficiencies and accuracies of TLS across the DNA lesion of interest (6, 18). Application of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing method, which affords complete ablation of TLS polymerases (19), enables unambiguous delineation of the roles of different TLS polymerases in bypassing these POB lesions in human cells.

In this study, we investigated, by employing a previously established double-stranded shuttle vector and SSPCR-CRAB assay (18), the effects of three stable POB lesions (O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, and O6-POB-dG) on the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication in HEK293T cells. Our results showed that O2-POB-dT is moderately blocking to the DNA replication machinery in human cells (Fig. 4A and Table S1), where the bypass efficiency was higher than what was reported previously (6). The difference could be attributed in part to the use of single- versus double-stranded lesion–containing plasmids for the replication experiments (6), where lesions in dsDNA are more efficiently repaired than in single-stranded DNA in mammalian cells (23, 24). We observed that, in addition to the previously reported roles of Pol η and Pol ζ (6), Pol ι was also involved in bypassing the O2-POB-dT lesion (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Although a number of O2-alkyl-dT lesions, including O2-POB-dT, were found to induce all three types of single-base substitutions (T→A, T→C, and T→G) in E. coli (11, 25), O2-POB-dT elicits exclusively T→A transversion in HEK293T cells, suggesting differences in recognition of the lesion by DNA replication machineries in bacterial and mammalian cells. Deletion of Pol η, Pol ι, or Pol ζ led to a marked reduction in mutation frequencies (Fig. 4B and Table S2).

We generated here, for the first time, HEK293T cells with both Pol η and Pol ζ being knocked out using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. We observed that dual depletion of Pol η and Pol ζ resulted in a more pronounced decline in bypass efficiency and mutation frequency than deletion of either polymerase alone (Fig. 4, A and B, and Tables S1 and S2), suggesting that Pol η and Pol ζ, aside from functioning together as inserter and extender, respectively, in supporting the replication across the O2-POB-dT lesion, may also act together with other TLS polymerases in bypassing this lesion. Interestingly, although loss of Pol κ did not affect the bypass efficiency, it resulted in a pronounced drop in mutation frequency, indicating a potential role of this polymerase in modulating O2-POB-dT-induced mutations.

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation of how O4-POB-dT affects the efficiency and fidelity of DNA replication. This lesion could also be induced in mammalian cells upon treatment with NNKOAc, albeit at levels that are several times lower than those of O2-POB-dT (10). We found that O4-POB-dT constitutes a stronger blockade to DNA replication than the regioisomeric O2-POB-dT and that the former lesion elicits exclusively T→C mutation (Fig. 4, A and B, and Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, replicative bypass of this lesion requires both Pol η and Pol ζ, but not Pol κ or Pol ι (Fig. 4A and Table S1). These results are in keeping with the findings of our previous replication studies regarding other O4-alkyl-dT lesions (19, 26, 27). In addition, both the bypass efficiencies and mutation frequencies were lower in Pol η/Pol ζ-double knockout cells than in the corresponding single knockout cells, which is in line with the observations made for O2-POB-dT (Fig. 4 and Tables S1 and S2). Because mounting evidence revealed human Pol ζ as an effective extender during lesion bypass (28–30), we reason that Pol η may insert one or a few nucleotides at and near the O4-POB-dT lesion site, followed by extension of the nascent DNA strand via Pol ζ. However, an appreciable level of bypass (∼8.5%) was still observed in double knockout cells (Fig. 4A and Table S1), indicating the involvement of replicative polymerases and/or other TLS polymerases in bypassing this lesion.

Our results showed that O6-POB-dG is not highly blocking to the DNA replication machinery in HEK293T cells, but the bypass efficiencies decreased significantly after depletion of any of the four TLS polymerases (Fig. 4A and Table S1). In addition, there was no significant difference in bypass efficiency for O6-POB-dG in HEK293T cells when Pol η was deleted alone or in combination with Pol ζ (Fig. 4A and Table S1). Although Pol ζ was found to be the most efficient polymerase functioning as an extender during translesion synthesis (29), it is formally possible that other TLS polymerases, e.g. Pol θ and Pol ν (31, 32), may also participate in the extension step of TLS across the O6-POB-dG lesion.

The major type of mutation observed for O6-POB-dG was G→A transition (∼75%), which is associated with a low frequency of G→T transversion (∼3%, Fig. 4D and Table S2). These results are in agreement with a previous replication study conducted using HEK293 cells (12). It is also worth noting that the mutation frequency of the lesion was not substantially modulated by depletion of any of the TLS polymerases (Fig. 4D and Table S2), supporting that O6-POB-dG is inherently miscoding and that it directs dTMP insertion by replicative and TLS polymerases. The high mutation frequency observed for the lesion suggests that it is not efficiently repaired prior to being encountered by the DNA replication machinery. Along this line, several recent studies have shown that O6-POB-dG can be directly repaired by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) (33, 34). Following the transfer of a methyl or other alkyl groups from O6-alkylguanine to an internal cysteine residue (Cys-145) of AGT, O6-dG adducts are repaired, and the protein becomes inactivated during the repair process (35, 36). Because the “suicide” AGT protein acts only once, the number of O6-alkylguanine adducts that can be repaired is limited to the number of AGT molecules available.

It is worth discussing our results in the context of mutations found in lung cancer patients. Previous genome-wide analysis of lung cancer patients revealed an enrichment of G→T transversion in somatic cells of tobacco smokers, whereas G→A transition constitutes the major type of somatic mutation in never-smokers (37, 38). In addition, G→C and A→T mutations display higher frequencies in somatic cells than the germline (39). Our results illustrated that replication across O2-POB-dT predominantly gives rise to T→A transversion mutation, whereas that of O6-POB-dG mainly leads to G→A transition together with a low frequency of G→T transversion (Fig. 4 and Table S2). Tobacco-induced G→T mutation in somatic cells was shown to be correlated with the N2-dG adducts induced by metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, especially benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide (40). Our results suggest that O2-POB-dT and O6-POB-dG may also contribute, in part, to the elevated frequencies of T→A and G→T mutations induced by cigarette smoking.

Taken together, we assessed the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of three stable POB DNA adducts that could be induced by tobacco-derived N-nitrosamines in HEK293T cells. We found that the replication blockage effects of these lesions follow the order of O6-POB-dG (with a bypass efficiency of 82%) < O2-POB-dT (54%) < O4-POB-dT (26.7%; Fig. 4A and Table S1). Although Pol κ and Pol ι assume different roles in bypassing these three lesions, both Pol η and Pol ζ are involved in the bypass of all three lesions, indicating the importance of the “inserter” Pol η and the “extender”, Pol ζ, in TLS of the bulky POB adducts in human cells. O6-POB-dG is highly mutagenic in HEK293T cells, where it induces mainly G→A transition along with a low frequency of G→T transversion (Fig. 4D and Table S2). O2-POB-dT and O4-POB-dT are less mutagenic, eliciting exclusively T→A transversion and T→C transition, respectively (Fig. 4 and Table S2). Hence, our study provides important new knowledge about the impact of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamine–derived POB lesions on the efficiency and accuracy of DNA replication and unveils the roles of TLS polymerases in bypassing these lesions in human cells.

Experimental procedures

All chemicals, unless otherwise specified, were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and all enzymes were from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA). 1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol was obtained from Oakwood Products Inc. (West Columbia, SC), and [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. All unmodified ODNs were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). HEK293T cells deficient in the POLH, POLI, POLK, and REV3L genes, which encode DNA polymerases η, ι, and κ and the catalytic subunit of polymerase ζ, were produced previously by using the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing method (19). The Pol η, Pol ζ double knockout HEK293T cells were obtained by deleting the POLH gene from REV3L−/− cells using the CRISPR-Cas9 method, following previously published procedures (19). The guide sequence for the human POLH gene was CTGCTCCCACGGTGAGCTGCAGG, with the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) motif underlined. The depletion of these two polymerases was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fig. S4).

Syntheses of ODNs containing site-specifically inserted O6-POB-dG, O2-POB-dT, and O4-POB-dT

The 12-mer ODNs containing a site-specifically incorporated POB lesion were synthesized following previously published procedures (10, 41, 42). The dithiane-protected ODNs were synthesized at a 1-μmol scale on a Beckman Oligo 1000 M DNA synthesizer, where ultramild phosphoramidite building blocks (Glen Research, Sterling, VA) were employed for ODN assembly. The ODNs were cleaved from the controlled pore glass support and deprotected with concentrated ammonium hydroxide at room temperature for 1 h. The solvents were evaporated, and the resulting solid residues were redissolved in water for HPLC purification. For the O6-POB-dG–containing ODNs, the N2-phenylacetyl group in the modified nucleoside was removed by treatment with 0.1 m NaOH overnight, and the solution was subsequently neutralized with 0.1 m HCl prior to HPLC purification. The dithiane protecting group was removed by incubating the aforementioned deprotected ODNs with N-chlorosuccinimide at a molar ratio of 1:5 in 50 μl of CH3CN:H2O (1/1, v/v) at room temperature for 10 min. The solution was chilled on ice until HPLC purification. The purified ODNs were then desalted by solid-phase extraction, where the samples were loaded onto an HLB Oasis column (Waters, Milford, MA) and washed with 1.0 ml of water, and the ODNs were eluted with 1.0 ml of 30% methanol in H2O. The HPLC separation was performed on an Agilent 1100 system with a Kinetex XB-C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, 5-μm particle size, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). For the purification of ODNs, a triethylammonium acetate buffer (50 mm (pH 6.8), solution A) and a mixture of solution A and acetonitrile (70/30, v/v, solution B) were employed as mobile phases. The flow rate was 0.6 ml/min, and the gradient profile in terms of solution B was 5–25% over 5 min followed by 25–60% over 60 min. The mass spectrometric characterizations of the purified lesion-containing ODNs are shown in Figs. S1–S3.

Construction of lesion-containing and control plasmids

The lesion-containing as well as the lesion-free control and competitor genomes were prepared following previously published procedures (18, 43, 44). First, the parent vector was digested with Nt.BstNBI to generate a gapped plasmid, followed by removal of the resultant 25-mer single-stranded ODN through annealing with a 50× excess of a 25-mer complementary ODN. The gapped plasmid was then isolated from the mixture by using 100-kDa cutoff ultracentrifugal filter units (Millipore). The purified gapped plasmid was annealed with a 5′-phosphorylated 13-mer lesion-free ODN (5′-AATTGAGTCGATG-3′) and a 5′-phosphorylated 12-mer lesion-carrying ODN, 5′-ATGGCGXGCTAT-3′ (X = O2-POB-dT, O4-POB-dT, or O6-POB-dG) or the corresponding lesion-free ODN, followed by incubation with T4 DNA ligase and ATP in the ligation buffer. It is worth noting that the resulting lesion-carrying and lesion-free plasmids contained a C/C mismatch two nucleotides away from the lesion site, which facilitated the differentiation of replication products formed from the lesion-containing strand and the unmodified complementary strand (Fig. 2).

Cell culture, transfection, and plasmid isolation

Replication of the above constructed genomes was performed using the previously reported SSPCR-CRAB assay (18, 45). The lesion-containing and the corresponding control plasmids were premixed individually with the competitor genome and transfected into HEK293T cells or the isogenic polymerase-deficient cells. The molar ratios of the competitor to control and lesion-bearing genome were 1:3 and 1:9, respectively. The cells (1 × 105) were seeded in 24-well plates and cultured overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, after which they were transfected with 300 ng of the mixed genomes by using TransIT-2020 (Mirus Bio Corp., Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's recommended procedures. The cells were harvested 24 h following transfection, and the progenies of the plasmid were isolated using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). The residual unreplicated plasmid was further removed by DpnI digestion, and the resulting linear DNA was removed by exonuclease III digestion as described elsewhere (18).

PCR amplification and PAGE analyses

The progeny genomes emanating from cellular DNA replication were amplified by nested PCR. The primers for the first amplification were 5′-TTGGCAGTACATCAATGGGCGTGGATAG-3′ and 5′-AGGGATTTTGCCGATTTCGGCCTATTG-3′, and the PCR amplification started at 98 °C for 2 min; then 35 cycles at 98 °C for 30 s, 61 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 40 s; and a final 5-min extension at 72 °C with the use of Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). The PCR products were purified using an E.Z.N.A. Cycle Pure Kit (Omega, Norcross, GA), and a nested PCR step was performed by using primers 5′-GCTAGCGGATGCATCGACTCAATTACAG-3′ (P1 primer) and 5′-ATGATCTTGTCGGTGAAGATCACGC-3′ and GoTaq Hot Start DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). In this vein, the P1 primer contained two mismatches with respect to the top-strand replication product (G/G and C/A mismatches) but only one mismatch with respect to the bottom-strand replication product (a C/A mismatch), thereby enabling selective amplification of the replication product(s) from the lesion-containing strand (Fig. 2). The PCR products were again purified using an E.Z.N.A. Cycle Pure Kit and stored at −20 °C until use.

For PAGE analysis, 150 ng of the PCR fragments were treated with 5 units of NcoI-HF and 1 unit of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) at 37 °C in 10 μl of NEBuffer 3 (New England Biolabs) for 1 h, followed by heating at 80 °C for 20 min to deactivate the SAP. To the above mixture were then added 0.5 pmol (1.25 μCi) of [γ-32P]ATP and 5 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK). The reaction was continued at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by heating at 75 °C for 20 min to deactivate the T4 polynucleotide kinase. To the above mixture was subsequently added 2.0 units SfaNI, and the solution was incubated at 37 °C for 1.5 h. The digestion was subsequently terminated by addition of 20 μl of formamide gel loading buffer. The above restriction digestion yielded a 16-mer radiolabeled fragment for the competitor genome and 13-mer fragments for the control or lesion-carrying genome (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the 13-mer fragment with a T→C mutation (13-mer C) could not be resolved from the nonmutagenic 13-mer T. We therefore employed a sequential digestion of MluCI followed by Cac8I, which yielded 10-mer radiolabeled fragments of the opposite strand that permitted differentiation of the nonmutagenic product from the product with the T→C mutation (Fig. 3, C and D). The digestion products were separated using 30% native polyacrylamide gel (acrylamide:bisacrylamide 19:1) and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis (Fig. 3, B and D). The effects of DNA lesions on replication efficiency and fidelity are represented by the RBE and MF, where the RBE values were calculated from the ratios of (lesion signal/competitor signal)/(nonlesion control signal/competitor signal).

Confirmation of mutagenic products by LC-MS/MS

The replication products were also confirmed by using LC-MS/MS analysis. Briefly, 2 μg of the PCR products described above were digested with 30 units of SfaNI and 15 units of SAP in 150 μl of NEBuffer 3 at 37 °C for 2 h, followed by deactivation of the phosphatase by heating at 80 °C for 20 min. To the mixture was added 50 units of NcoI, and the solution was incubated at 37 °C for another 2 h. The resulting solution was extracted once with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v/v), and to the mixture were subsequently added 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol and 0.1 volume of 3.0 m sodium acetate to precipitate the DNA. The DNA pellet was then reconstituted in water and subjected to LC-MS and MS/MS analyses. An Agilent 1200 capillary HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and an LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) were used for all LC-MS and MS/MS experiments. The mass spectrometer was set up for monitoring the fragmentation of the [M-3H]3− ions of the 13-mer 5′-AATTACAGCNCGC-3′, where N represents A, T, C, or G (Fig. S7–S9).

Author contributions

H. D. and Y. W. conceptualization; H. D. and P. W. data curation; H. D. and Y. W. formal analysis; H. D. and Y. W. investigation; H. D., J. L., and L. L. methodology; H. D. and J. L. writing-original draft; J. L. and L. L. resources; P. W. visualization; Y. W. funding acquisition; Y. W. project administration; Y. W. writing-review and editing.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 ES025121. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S9 and Tables S1 and S2.

- NNK

- 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- NNN

- N′-nitrosonornicotine

- POB

- 4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobut-1-yl

- NNKOAc

- 4-(acetoxymethylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone

- Pol

- polymerase

- TLS

- translesion synthesis

- SSPCR-CRAB

- strand-specific PCR-competitive replication and adduct bypass

- ODN

- oligodeoxyribonucleotide

- RBE

- relative bypass efficiency

- MF

- mutation frequency

- HEK

- human embryonic kidney

- AGT

- O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase

- SAP

- shrimp alkaline phosphatase.

References

- 1. Shopland D. R. (1995) Tobacco use and its contribution to early cancer mortality with a special emphasis on cigarette smoking. Environ. Health Persp. 103, 131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pfeifer G. P., Denissenko M. F., Olivier M., Tretyakova N., Hecht S. S., and Hainaut P. (2002) Tobacco smoke carcinogens, DNA damage and p53 mutations in smoking-associated cancers. Oncogene 21, 7435–7451 10.1038/sj.onc.1205803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hecht S. S. (2003) Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 733–744 10.1038/nrc1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlson E. S., Upadhyaya P., and Hecht S. S. (2016) Evaluation of nitrosamide formation in the cytochrome P450-mediated metabolism of tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 2194–2205 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Crespi C. L., Penman B. W., Gelboin H. V., and Gonzalez F. J. (1991) A tobacco smoke-derived nitrosamine, 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone, is activated by multiple human cytochrome P450s including the polymorphic human cytochrome P4502d6. Carcinogenesis 12, 1197–1201 10.1093/carcin/12.7.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weerasooriya S., Jasti V. P., Bose A., Spratt T. E., and Basu A. K. (2015) Roles of translesion synthesis DNA polymerases in the potent mutagenicity of tobacco-specific nitrosamine-derived O2-alkylthymidines in human cells. DNA Repair 35, 63–70 10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.09.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hecht S. S. (1999) DNA adduct formation from tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. Mutat. Res. 424, 127–142 10.1016/S0027-5107(99)00014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Peterson L. A., Liu X. K., and Hecht S. S. (1993) Pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts inhibit the repair of O6-methylguanine. Cancer Res. 53, 2780–2785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Urban A. M., Upadhyaya P., Cao Q., and Peterson L. A. (2012) Formation and repair of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts and their relationship to tumor yield in A/J mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 2167–2178 10.1021/tx300245w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leng J., and Wang Y. (2017) Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the quantification of tobacco-specific nitrosamine-induced DNA adducts in mammalian cells. Anal. Chem. 89, 9124–9130 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jasti V. P., Spratt T. E., and Basu A. K. (2011) Tobacco-specific nitrosamine-derived O2-alkylthymidines are potent mutagenic lesions in SOS-induced Escherichia coli. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 24, 1833–1835 10.1021/tx200435d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pauly G. T., Peterson L. A., and Moschel R. C. (2002) Mutagenesis by O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine in Escherichia coli and human cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 15, 165–169 10.1021/tx0101245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li L., Perdigao J., Pegg A. E., Lao Y., Hecht S. S., Lindgren B. R., Reardon J. T., Sancar A., Wattenberg E. V., and Peterson L. A. (2009) The influence of repair pathways on the cytotoxicity and mutagenicity induced by the pyridyloxobutylation pathway of tobacco-specific nitrosamines. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 22, 1464–1472 10.1021/tx9001572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albertson T. M., Ogawa M., Bugni J. M., Hays L. E., Chen Y., Wang Y., Treuting P. M., Heddle J. A., Goldsby R. E., and Preston B. D. (2009) DNA polymerase ϵ and δ proofreading suppress discrete mutator and cancer phenotypes in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17101–17104 10.1073/pnas.0907147106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCulloch S. D., and Kunkel T. A. (2008) The fidelity of DNA synthesis by eukaryotic replicative and translesion synthesis polymerases. Cell Res. 18, 148–161 10.1038/cr.2008.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo C., Fischhaber P. L., Luk-Paszyc M. J., Masuda Y., Zhou J., Kamiya K., Kisker C., and Friedberg E. C. (2003) Mouse Rev1 protein interacts with multiple DNA polymerases involved in translesion DNA synthesis. EMBO J. 22, 6621–6630 10.1093/emboj/cdg626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pustovalova Y., Magalhães M. T. Q., D'Souza S., Rizzo A. A., Korza G., Walker G. C., and Korzhnev D. M. (2016) Interaction between the Rev1 C-terminal domain and the PolD3 subunit of Pol ζ suggests a mechanism of polymerase exchange upon Rev1/Pol ζ-dependent translesion synthesis. Biochemistry 55, 2043–2053 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. You C., Swanson A. L., Dai X., Yuan B., Wang J., and Wang Y. (2013) Translesion synthesis of 8,5′-cyclopurine-2′-deoxynucleosides by DNA polymerases η, ι, and ζ. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28548–28556 10.1074/jbc.M113.480459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu J., Li L., Wang P., You C., Williams N. L., and Wang Y. (2016) Translesion synthesis of O4-alkylthymidine lesions in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 9256–9265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gowda A. S., and Spratt T. E. (2016) DNA polymerases η and ζ combine to bypass O2-[4-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutyl]thymine, a DNA adduct formed from tobacco carcinogens. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 303–316 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gowda A. S., Krishnegowda G., Suo Z., Amin S., and Spratt T. E. (2012) Low fidelity bypass of O2-(3-pyridyl)-4-oxobutylthymine, the most persistent bulky adduct produced by the tobacco specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone by model DNA polymerases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 25, 1195–1202 10.1021/tx200483g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ronai Z. A., Gradia S., Peterson L. A., and Hecht S. S. (1993) G to A transitions and G to T transversions in codon 12 of the Ki-ras oncogene isolated from mouse lung tumors induced by 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) and related DNA methylating and pyridyloxobutylating agents. Carcinogenesis 14, 2419–2422 10.1093/carcin/14.11.2419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takeshita M., and Eisenberg W. (1994) Mechanism of mutation on DNA templates containing synthetic abasic sites: study with a double strand vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 1897–1902 10.1093/nar/22.10.1897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sancar A., Lindsey-Boltz L. A., Unsal-Kaçmaz K., and Linn S. (2004) Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 39–85 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhai Q., Wang P., Cai Q., and Wang Y. (2014) Syntheses and characterizations of the in vivo replicative bypass and mutagenic properties of the minor-groove O2-alkylthymidine lesions. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 10529–10537 10.1093/nar/gku748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhai Q., Wang P., and Wang Y. (2014) Cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of regioisomeric O2-, N3-and O4-ethylthymidines in bacterial cells. Carcinogenesis 35, 2002–2006 10.1093/carcin/bgu085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang P., Amato N. J., Zhai Q., and Wang Y. (2015) Cytotoxic and mutagenic properties of O4-alkylthymidine lesions in Escherichia coli cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 10795–10803 10.1093/nar/gkv941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu D., Ryu K. S., Ko J., Sun D., Lim K., Lee J. O., Hwang Jm., Lee Z. W., and Choi B. S. (2013) Insights into the regulation of human Rev1 for translesion synthesis polymerases revealed by the structural studies on its polymerase-interacting domain. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 5, 204–206 10.1093/jmcb/mjs061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lawrence C. W. (2002) Cellular roles of DNA polymerase ζ and Rev1 protein. DNA Repair 1, 425–435 10.1016/S1568-7864(02)00038-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gan G. N., Wittschieben J. P., Wittschieben B. Ø., and Wood R. D. (2008) DNA polymerase ζ (Pol ζ) in higher eukaryotes. Cell Res. 18, 174–183 10.1038/cr.2007.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yousefzadeh M. J., and Wood R. D. (2013) DNA polymerase POLQ and cellular defense against DNA damage. DNA Repair 12, 1–9 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moldovan G. L., Madhavan M. V., Mirchandani K. D., McCaffrey R. M., Vinciguerra P., and D'Andrea A. D. (2010) DNA polymerase POLN participates in cross-link repair and homologous recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 1088–1096 10.1128/MCB.01124-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kotandeniya D., Murphy D., Yan S., Park S., Seneviratne U., Koopmeiners J. S., Pegg A., Kanugula S., Kassie F., and Tretyakova N. (2013) Kinetics of O6-pyridyloxobutyl-2′-deoxyguanosine repair by human O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. Biochemistry 52, 4075–4088 10.1021/bi4004952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guza R., Pegg A. E., and Tretyakova N. (2010) Effects of sequence context on O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase repair of O6-alkyl-deoxyguanosine adducts. ACS Sym. Ser. 1041, 73–101 10.1021/bk-2010-1041.ch006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guengerich F. P., Fang Q., Liu L., Hachey D. L., and Pegg A. E. (2003) O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: low pKa and high reactivity of cysteine 145. Biochemistry 42, 10965–10970 10.1021/bi034937z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gerson S. L. (1988) Regeneration of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase in human lymphocytes after nitrosourea exposure. Cancer Res. 48, 5368–5373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Govindan R., Ding L., Griffith M., Subramanian J., Dees N. D., Kanchi K. L., Maher C. A., Fulton R., Fulton L., Wallis J., Chen K., Walker J., McDonald S., Bose R., Ornitz D., et al. (2012) Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell 150, 1121–1134 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sun S., Schiller J. H., and Gazdar A. F. (2007) Lung cancer in never smokers: a different disease. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 778–790 10.1038/nrc2190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee W., Jiang Z., Liu J., Haverty P. M., Guan Y., Stinson J., Yue P., Zhang Y., Pant K. P., Bhatt D., Ha C., Johnson S., Kennemer M. I., Mohan S., Nazarenko I., et al. (2010) The mutation spectrum revealed by paired genome sequences from a lung cancer patient. Nature 465, 473–477 10.1038/nature09004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Denissenko M. F., Pao A., Tang M., and Pfeifer G. P. (1996) Preferential formation of benzo[a]pyrene adducts at lung cancer mutational hotspots in P53. Science 274, 430–432 10.1126/science.274.5286.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang L., Spratt T. E., Pegg A. E., and Peterson L. A. (1999) Synthesis of DNA oligonucleotides containing site-specifically incorporated O6-[4-oxo-4-(3-pyridyl)butyl]guanine and their reaction with O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 12, 127–131 10.1021/tx980251+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lao Y., Villalta P. W., Sturla S. J., Wang M., and Hecht S. S. (2006) Quantitation of pyridyloxobutyl DNA adducts of tobacco-specific nitrosamines in rat tissue DNA by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19, 674–682 10.1021/tx050351x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yuan B., O'Connor T. R., and Wang Y. (2010) 6-Thioguanine and S6-methylthioguanine are mutagenic in human cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 5, 1021–1027 10.1021/cb100214b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. You C., and Wang Y. (2015) Quantitative measurement of transcriptional inhibition and mutagenesis induced by site-specifically incorporated DNA lesions in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Protoc. 10, 1389–1406 10.1038/nprot.2015.094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Delaney J. C., and Essigmann J. M. (2008) Biological properties of single chemical-DNA adducts: a twenty year perspective. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 232–252 10.1021/tx700292a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.