Attachment receptors expressed on the host cell surface are thought to enhance EV71 infection by increasing the chance of encountering true receptors. Although this has been confirmed using cell culture for some viruses, the importance of attachment receptors in vivo is unknown. This report provides an unexpected answer to this question. We demonstrated that the VP1-145G virus binds to HS and shows an attenuated phenotype in an hSCARB2-dependent animal infection model. HS is highly expressed in cells that express hSCARB2 at low or undetectable levels. Our data indicate that HS binding directs VP1-145G virus toward abortive infection and keeps virus away from hSCARB2-positive cells. Thus, although the ability of VP1-145G virus to use HS might be an advantage in replication in certain cultured cells, it becomes a serious disadvantage in replication in vivo. This adsorption is thought to be a major mechanism of attenuation associated with attachment receptor usage.

KEYWORDS: animal models, enterovirus, pathogenesis, receptors

ABSTRACT

Infection by enterovirus 71 (EV71) is affected by cell surface receptors, including the human scavenger receptor B2 (hSCARB2), which are required for viral uncoating, and attachment receptors, such are heparan sulfate (HS), which bind virus but do not support uncoating. Amino acid residue 145 of the capsid protein VP1 affects viral binding to HS and virulence in mice. However, the contribution of this amino acid to pathogenicity in humans is not known. We produced EV71 having glycine (VP1-145G) or glutamic acid (VP1-145E) at position 145. VP1-145G, but not VP1-145E, enhanced viral infection in cell culture in an HS-dependent manner. However, VP1-145G virus showed an attenuated phenotype in wild-type suckling mice and in a transgenic mouse model expressing hSCARB2, while VP1-145E virus showed a virulent phenotype in both models. Thus, the HS-binding property and in vivo virulence are negatively correlated. Immunohistochemical analyses showed that HS is highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells and some other cell types where hSCARB2 is expressed at low or undetectable levels. VP1-145G virus bound to tissue homogenate of both hSCARB2 transgenic and nontransgenic mice in vitro, and the viral titer was reduced in the bloodstream immediately after intravenous inoculation. Furthermore, VP1-145G virus failed to disseminate well in the mouse organs. These data suggest that VP1-145G virus is adsorbed by attachment receptors such as HS during circulation in vivo, leading to abortive infection of HS-positive cells. This trapping effect is thought to be a major mechanism of attenuation of the VP1-145G virus.

IMPORTANCE Attachment receptors expressed on the host cell surface are thought to enhance EV71 infection by increasing the chance of encountering true receptors. Although this has been confirmed using cell culture for some viruses, the importance of attachment receptors in vivo is unknown. This report provides an unexpected answer to this question. We demonstrated that the VP1-145G virus binds to HS and shows an attenuated phenotype in an hSCARB2-dependent animal infection model. HS is highly expressed in cells that express hSCARB2 at low or undetectable levels. Our data indicate that HS binding directs VP1-145G virus toward abortive infection and keeps virus away from hSCARB2-positive cells. Thus, although the ability of VP1-145G virus to use HS might be an advantage in replication in certain cultured cells, it becomes a serious disadvantage in replication in vivo. This adsorption is thought to be a major mechanism of attenuation associated with attachment receptor usage.

INTRODUCTION

Enterovirus 71 (EV71), belonging to the genus Enterovirus of the family Picornaviridae, is a causative agent of hand, foot, and mouth disease together with other members of human enterovirus species A (HEV-A) (1). Unlike the case for other members of HEV-A, infection with EV71 is sometimes associated with severe neurological diseases. Since the late 1990s, large outbreaks have repeatedly occurred in Asian countries (2–6).

The virulence of EV71 has been assessed using suckling mice because many, but not all, EV71 strains can infect suckling mice. Molecular genetic analysis revealed that mutation at amino acid residue 145 of capsid protein VP1 (VP1-145) plays an important role in suckling mouse infection (7–11). Viruses that have glutamic acid (E), but not glycine (G) or glutamine (Q), at this position can kill the suckling mice. This residue is therefore thought to act as a mouse adaptation determinant. Namely, EV71 that has E at VP1-145 (VP1-145E) might acquire binding affinity to an unknown molecule(s) that acts as a receptor(s) in suckling mice. The receptor molecule for this infection has not been identified. However, the contribution of this amino acid variation to pathogenicity in humans is a matter of debate. Some investigators reported that VP1-145G or VP1-145Q viruses are more frequently isolated from severely affected than from mildly affected patients, although the majority of viruses isolated from both types of patients have E at VP1-145 (12–16). Thus, it is not certain whether VP1-145E is virulent in humans.

Human scavenger receptor B2 (hSCARB2) is a receptor for all EV71 strains (17). Mouse cultured cells are not susceptible to EV71 infection because of the lack of appropriate receptors. Expression of hSCARB2 confers susceptibility to mouse cells. Although hSCARB2 is abundant in lysosomes, a small portion of hSCARB2 protein is also detected at the cell surface (17). hSCARB2 binds to and internalizes viruses and initiates conformational change leading to uncoating of the viral genomic RNA (18). Coxsackievirus A (CVA) 7, 14, and 16 can also infect cells via hSCARB2 (19). These results suggested that hSCARB2 plays the most important role in the early events of EV71 infection in vitro and determines the host range specificity of EV71 infection. In fatal human cases, EV71 antigens were detected in neurons and squamous cells in the crypts of palatine tonsils, in which hSCARB2 is expressed (20). Furthermore, adult mice that express hSCARB2 become susceptible to EV71 (21). These results suggested that hSCARB2 is important in infection in vivo.

In addition to hSCARB2, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand (PSGL-1) (22), heparan sulfate (HS) (23), annexin II (24), sialic acid (25), nucleolin (26), and vimentin (27) can bind EV71 and enhance infection. These molecules are considered to be “attachment receptors” because there is no evidence for initiation of virion uncoating after binding to them. Although the enhancement of EV71 infection by these molecules in cell culture was reported, their contribution in vivo has not been assessed. VP1-145 influences the capacity of the virus for binding to HS (28) and PSGL-1 (29). VP1-145G and VP1-145Q viruses can bind these attachment receptors. HS, a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan (GAG), is expressed as HS proteoglycan on cell surfaces in its membrane-bound form and on the extracellular matrix in its secreted form (30). The surface of the EV71 virion around the 5-fold axis is rich in positively charged amino acids, allowing electrostatic interaction with negatively charged molecules such as HS or highly sulfated PSGL-1. However, their contribution to virulence in animals has not been evaluated.

Here, we constructed VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses and assessed their replication in cultured cells and their virulence in hSCARB2 transgenic (tg) mice. VP1-145G virus showed better replication in cultured cells, but VP1-145E virus was more virulent in hSCARB2 tg mice. The VP1-145G virus could not maintain a high viremia titer after intravenous (i.v.) infection in mice and failed to replicate well in the organs of hSCARB2 tg mice. Immunohistochemical staining revealed HS expression mainly in hSCARB2-negative cells in vivo. VP1-145G viruses were adsorbed to peripheral tissues, likely by HS immediately after inoculation. Even after entering the central nervous system (CNS), VP1-145G viruses were adsorbed by nonneuronal cells, which have high HS expression. We propose that this trapping effect by HS may be one of the mechanisms of VP1-145G virus attenuation.

RESULTS

Production and in vitro characterization of VP1-145 mutants.

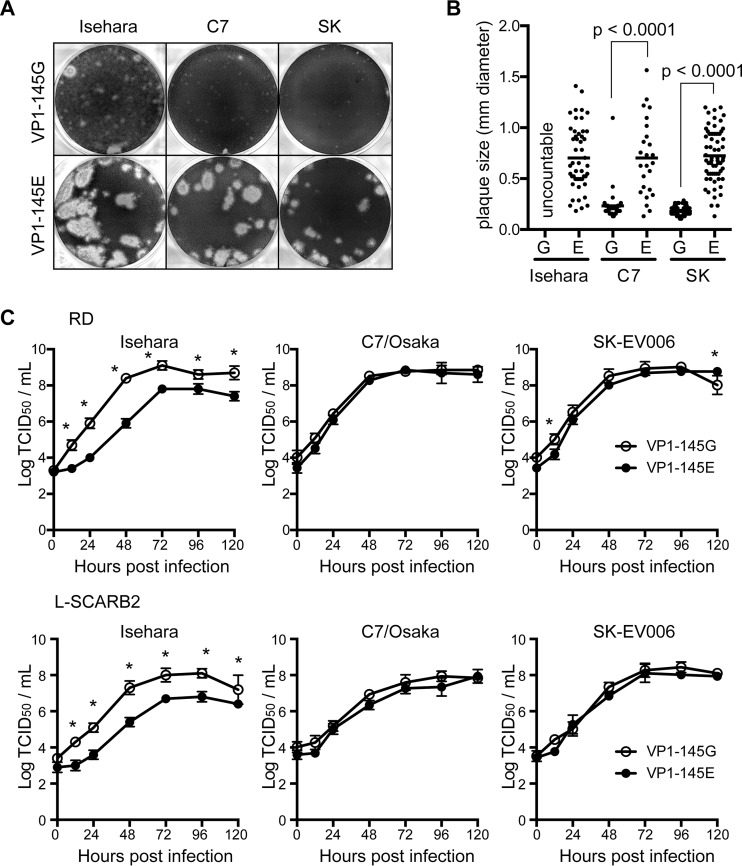

We constructed infectious cDNA clones for the Isehara, C7/Osaka, and SK-EV006 strains, which belong to subgenogroups C2, B4, and B2, respectively. The nucleotide identities between Isehara and C7/Osaka, C7/Osaka and SK-EV006, and SK-EV006 and Isehara were 80.37, 88.37, and 80.38%, respectively. The amino acid identities were 95.98, 97.67, and 95.94%, respectively. The original Isehara strain has E, whereas C7/Osaka and SK-EV006 have G, at VP1-145. We introduced E-to-G or G-to-E mutations in these strains by modifying the infectious cDNA clones. All the viruses were viable after transfection of in vitro-transcribed RNA into hSCARB2-overexpressing RD-A cells (RD-SCARB2 cells). These viruses, referred to as Isehara-E, Isehara-G, C7-E, C7-G, SK-E, and SK-G, replicated and formed plaques in RD-A cells (Fig. 1). The VP1-145E viruses of all three strains showed large-plaque phenotypes, while VP1-145G viruses showed small-plaque phenotypes (Fig. 1A and B). Isehara-G plaques were very small and sometimes difficult to count, whereas C7-G and SK-G formed clear small plaques (Fig. 1A). We propagated the viruses in RD-SCARB2 cells, titrated them using Vero cells, and subjected them to further experiments. We performed direct sequencing analysis and confirmed that the sequence of each recovered virus was identical to that of the original infectious cDNA.

FIG 1.

In vitro characterization of VP1-145 mutants. (A) The amino acid at VP1-145 affects the plaque phenotype of EV71. VP1-145 mutant viruses recovered from RD-SCARB2 cells transfected with in vitro-transcribed RNA of each mutant virus were used for plaque assays. After 4 days, cells were fixed and stained. (B) Plaque sizes were measured using a plaque counter (SK-Electronics, Japan). Significant differences between the plaque sizes of the VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses were assessed by using the t test. (C) VP1-145 mutant viruses were inoculated into RD-A and L-SCARB2 cells at a multiplicity of infection of 0.001. Infected cells were harvested to determine the virus titer by microplate assay. Asterisks indicate significant differences between VP1-145G and VP1-145E (two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple-comparison test).

We compared growth kinetics of the viruses in RD-A cells and mouse L929 cells expressing hSCARB2 (L-SCARB2 cells) (Fig. 1C). We infected EV71 strains at a multiplicity of infection of 0.001 and determined the virus titer at several time points up to 120 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 1C). All viruses replicated well in human RD-A cells. Isehara-G grew significantly better in RD-A cells than Isehara-E. VP1-145E and VP1-145G grew with similar kinetics for the C7/Osaka and SK-EV006 strains. These results suggested that VP1-145G viruses grow better than or as well as VP1-145E viruses in vitro. Viral replication in L-SCARB2 cells was similar to that in RD-A cells (Fig. 1C), suggesting that both VP1-145E and VP1-145G viruses can also replicate in the mouse background.

VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses replicate in an hSCARB2-dependent manner, and VP1-145G viruses replicate in an HS-dependent manner.

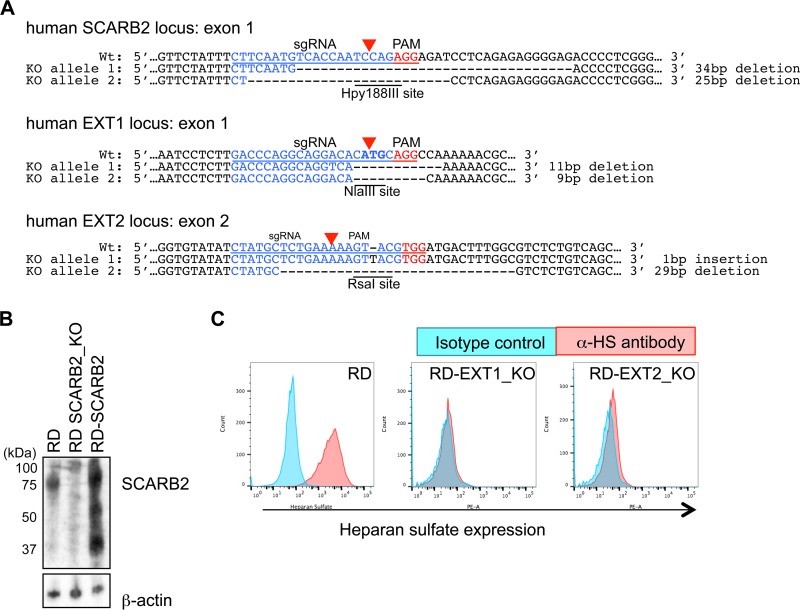

To evaluate the requirement of hSCARB2 for infection by VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses, we established hSCARB2-deficient cells (RD-SCARB2_KO) using the CRISPR-Cas9 system (Fig. 2A) and hSCARB2 overexpression cells (RD-SCARB2) using a retrovirus vector. hSCARB2 expression in the RD-SCARB2_KO and RD-SCARB2 cells was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 2B). To assess the requirement of hSCARB2 for these viruses, we determined the virus titers of Isehara-G and Isehara-E in RD-A cells, RD-SCARB2_KO cells, and RD-SCARB2 cells (Fig. 3A). Neither Isehara-G nor Isehara-E showed any signs of infection in SCARB2_KO cells. Furthermore, virus titers in RD-SCARB2 cells were 2.3- and 116-fold higher than those in RD-A cells for Isehara-G and Isehara-E infection, respectively. These results suggested that infection by both Isehara-G and Isehara-E is dependent on hSCARB2. Results similar to those with the Isehara strain were obtained using the C7/Osaka and SK-EV006 strains.

FIG 2.

Establishment of SCARB2, EXT1, and EXT2 knockout RD-A cells. (A) Target sequences of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences specific to each gene and corresponding protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM) sequences are shown in blue and red, respectively. Genomic sequences of established knockout cells are shown below the wild-type sequences. The length of deletion or insertion is shown to the right of each allele. A start codon is indicated in bold. Restriction enzyme recognition sequences are underlined. (B) Western blotting of hSCARB2 expression in RD-A, RD-SCARB2 KO, and RD-SCARB2 cells. (C) Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis of HS expression at the cell surface.

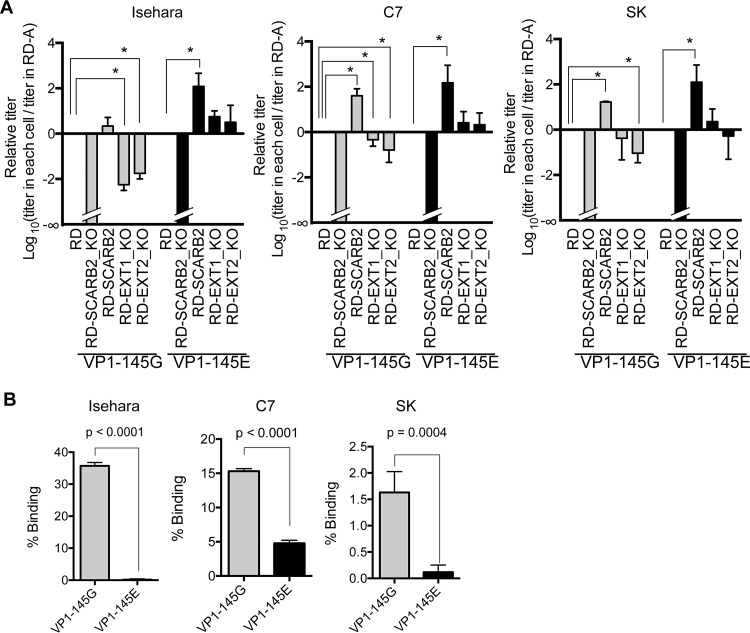

FIG 3.

VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses replicate in an hSCARB2-dependent manner, and VP1-145G viruses replicate in an HS-dependent manner. (A) Relative infectivities of the VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses in RD-A, RD-SCARB2_KO, RD-SCARB2, RD-EXT1_KO, and RD-EXT2_KO RD cells. Titers of VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses were measured using these cells. The results are indicated as values relative to the titer in RD-A cells on a logarithmic scale. Asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05 using a one-sided t test compared with the virus titer in RD-A cells. (B) VP1-145 mutant binding to heparin-agarose beads was determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). The P values were determined by the t test.

We also established HS-deficient cells (RD-EXT1KO and RD-EXT2KO) using CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. 2A) to analyze the contribution of HS to VP1-145G and VP1-145E virus infection. Expression of HS at the cell surface was greatly reduced in both KO cells (Fig. 2C). The apparent titer of Isehara-G, but not Isehara-E, in RD-EXT1KO and RD-EXT2KO cells was significantly lower than that in RD-A cells (Fig. 3A). These results suggest that infection by Isehara-G in RD-A cells is largely dependent on HS, whereas infection by Isehara-E is not. The results for C7/Osaka and SK-EV006 were similar to those for the Isehara strain. To confirm this, we examined binding of the viruses to heparin-agarose (Fig. 3B). VP1-145G, but not VP1-145E, viruses clearly bound to heparin-agarose, in agreement with previous reports (28). In summary, VP1-145G virus infection in RD-A cells is dependent on both HS and hSCARB2, whereas VP1-145E virus infection is dependent only on hSCARB2.

VP1-145E viruses are more virulent than VP1-145G viruses.

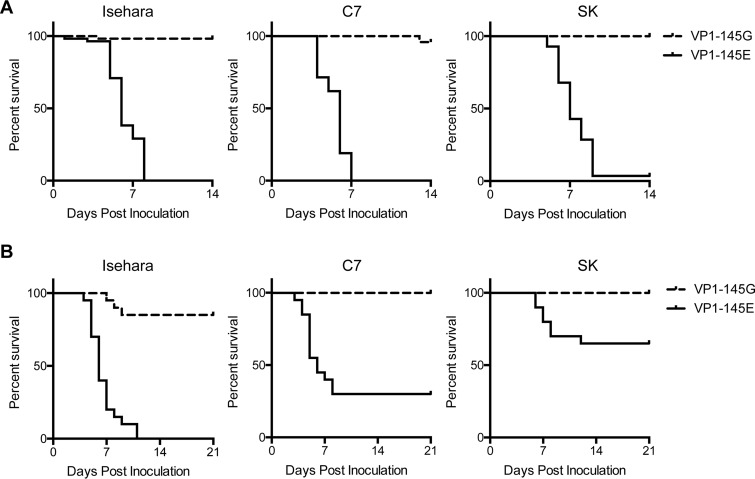

We compared the virulence of the viruses in suckling mice. We inoculated a total of 106 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses in ICR suckling mice intraperitoneally (i.p.), and we observed paralysis and death over the course of 2 weeks (Fig. 4A). Consistent with previous reports (8, 9, 11), Isehara-E killed all the mice and was virulent in suckling mice, whereas Isehara-G killed only 3.4% of the infected mice. Similar results were obtained using the C7/Osaka and SK-EV006 strains (P < 0.0001 by the log rank test in all experiments) (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

VP1-145E viruses are more virulent than VP1-145G viruses in suckling mice and in an hSCARB2 tg mouse model. Survival curves for ICR suckling mice (106 TCID50, i.p.) (A) and hSCARB2 tg mice (106 TCID50, i.v.) (B) inoculated with VP1-145 mutant viruses are shown. Death of inoculated mice was observed over 14 (A) or 21 (B) days.

We also inoculated 106 TCID50 of VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses into hSCARB2 tg mice intravenously (Fig. 4B). Isehara-E killed all the mice within 5 to 10 days postinfection (dpi), whereas Isehara-G killed few mice (P < 0.0001, log rank test). The C7-E and SK-E strains killed 70% and 35% of infected mice, respectively. VP1-145G of these strains killed no mice (P < 0.0001 for C7/Osaka and P = 0.0039 for SK-EV006 by the log-rank test).

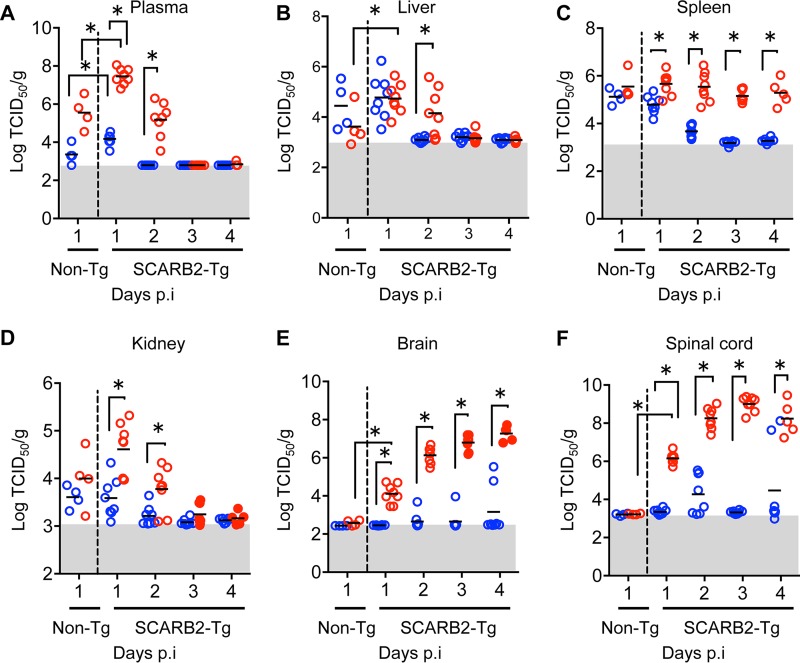

We determined the viral replication in organs of hSCARB2 tg mice after intravenous inoculation with Isehara-G and Isehara-E (Fig. 5). The virus titer at 1 dpi in plasma (Fig. 5A) of hSCARB2 tg mice was higher than that in non-tg mice, suggesting that virus replication occurred in the organs of hSCARB2 tg mice. The viral loads of Isehara-E in plasma (Fig. 5A) and nonneural organs such as liver (Fig. 5B), spleen (Fig. 5C), and kidney (Fig. 5D) of hSCARB2 tg mice were higher than those of Isehara-G. The viruses in plasma, liver, and kidney were almost gone at 3 dpi. High levels of Isehara-E were detected in brain (Fig. 5E) and spinal cord (Fig. 5F) in all infected mice at 1 dpi, and the titer increased over time. In contrast, virus titers at moderate levels were observed in only some of the mice infected with Isehara-G. Titers of Isehara-E in brain and spinal cord were significantly higher than those of Isehara-G at 1 to 4 dpi, suggesting that Isehara-E can replicate more efficiently in hSCARB2 tg mice than Isehara-G.

FIG 5.

Isehara-E replicates in organs of hSCARB2 tg mice more efficiently than Isehara-G. hSCARB2 tg or non-tg mice were intravenously inoculated with 106 TCID50 of Isehara-G or Isehara-E. Plasma (A), livers (B), spleens (C), kidneys (D), brains (E), and spinal cords (F) of infected mice were harvested at 1 to 4 dpi and homogenized. Virus titers in the organs were determined using RD-SCARB2 cells. Red and blue dots indicate the results for Isehara-E and Isehara-G, respectively. Closed and open circles indicate mice with or without paralysis, respectively. The horizontal bars indicate the mean value for six mice. The shaded areas are below the detection limits. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05 by t test).

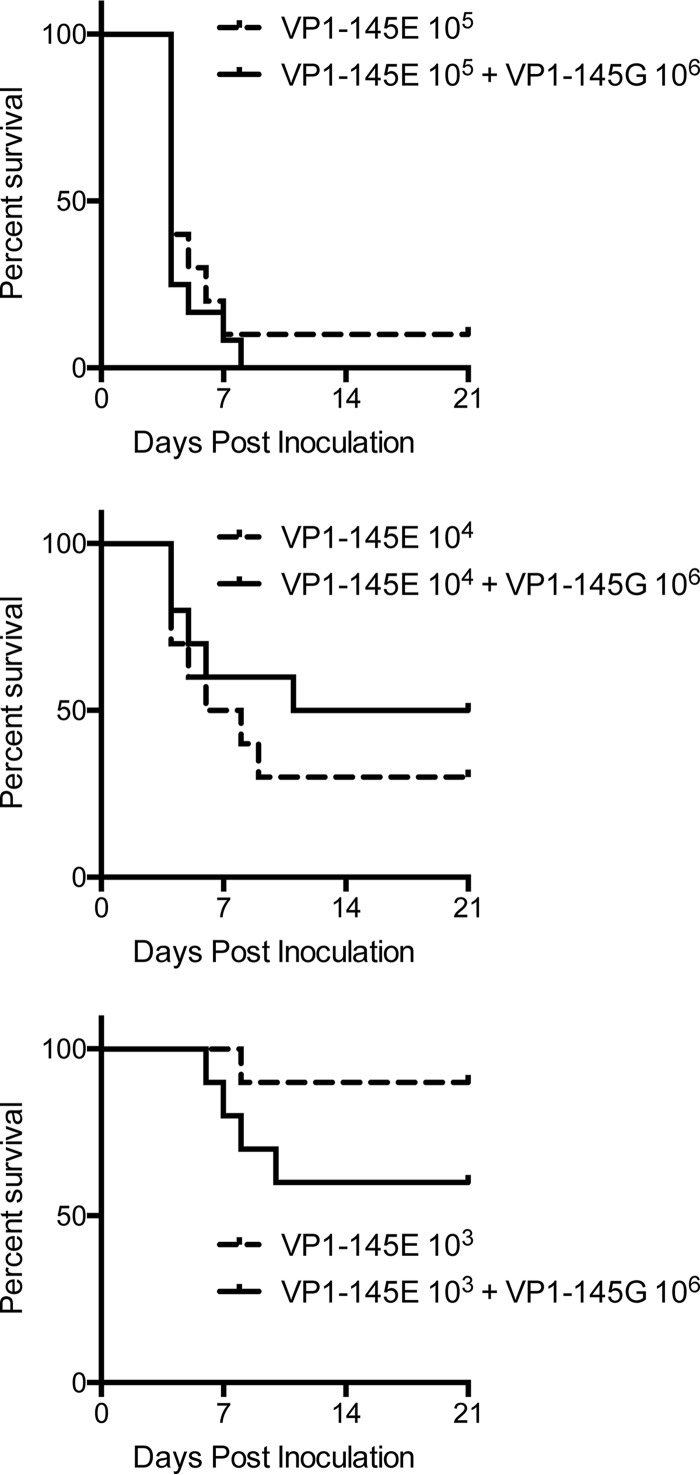

To confirm that VP1-145E virus is virulent in hSCARB2 tg mice, we inoculated Isehara-E alone at different doses (103, 104, or 105 TCID50) or a mixture of Isehara-G (106 TCID50) with different doses of Isehara-E (103, 104, or 105 TCID50) intravenously. The mortality rates of the mice inoculated with the virus mixtures were dependent on the amount of Isehara-E and were similar to those of mice inoculated with the same dose of Isehara-E alone (Fig. 6). Statistical differences between the two groups were not observed by the log rank test. In addition, we recovered the virus from paralyzed or dead mice and determined the sequence of the P1 region. All recovered viruses showed sequences identical to that of the inoculated Isehara-E without contamination from Isehara-G. Therefore, Isehara-E mainly contributed to the CNS disease even when both viruses were inoculated.

FIG 6.

Isehara-G does not contribute to virulence of EV71. hSCARB2 tg mice were inoculated intravenously with different amounts of Isehara-E (103 to 105 TCID50) with or without Isehara-G (106 TCID50). Death of inoculated mice was observed over 21 days.

Although Isehara-G was not virulent, a small proportion of infected mice showed paralysis and death when a large number of mice were infected. We performed intravenous infection with Isehara-G in 30 mice. Two mice out of 30 were paralyzed or died. The viruses recovered from the CNS of paralyzed or dead mice were analyzed for the sequence of the P1 region and plaque size (Table 1). Viruses recovered from the dead mice showed a G-to-E amino acid mutation at VP1-145 and a synonymous mutation of G to A at nucleotide (nt) 1602 (VP2-221). Viruses recovered from the paralyzed mice showed a G-to-E amino acid mutation at VP1-145 and a synonymous mutation of A to G at nt 2574 (VP1-35). These viruses formed large plaques (Table 1). We also performed intracerebral (i.c.) infection with 105 TCID50 of Isehara-G, and three mice out of 10 were paralyzed. The recovered viruses showed a G-to-E substitution at VP1-145 and a large-plaque phenotype (Table 1). Together, these results support the notion that Isehara-E replicates efficiently in the CNS and shows a virulent phenotype in hSCARB2 tg mice.

TABLE 1.

Infection of mice with Isehara-G virus

| Expt | Inoculation route, TCID50 | Manifestation | Nucleotide mutation | Amino acid mutation | Plaque diam, mm (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | i.v., 106 | Dead | 1602 G → A | VP2-221 V → V | 2.10 ± 0.816 |

| 2873 G → A | VP1-145 G → E | ||||

| i.v., 106 | Paralyzed | 2574 A → G | VP1-35 P → P | 1.20 ± 0.752 | |

| 2873 G → A | VP1-145 G → E | ||||

| VP1-145G control | 0.54 ± 0.028 | ||||

| VP1-145E control | 1.75 ± 0.996 | ||||

| 2 | i.c., 105 | Paralyzed | 2873 G → A | VP1-145 G → E | 2.26 ± 0.508 |

| i.c., 105 | Paralyzed | 2873 G → A | VP1-145 G → E | 1.95 ± 0.117 | |

| i.c., 105 | Paralyzed | 2873 G → A | VP1-145 G → E | 2.33 ± 0.362 | |

| VP1-145G control | 0.58 ± 0.060 | ||||

| VP1-145E control | 2.02 ± 0.526 |

HS expression in hSCARB2 tg mice.

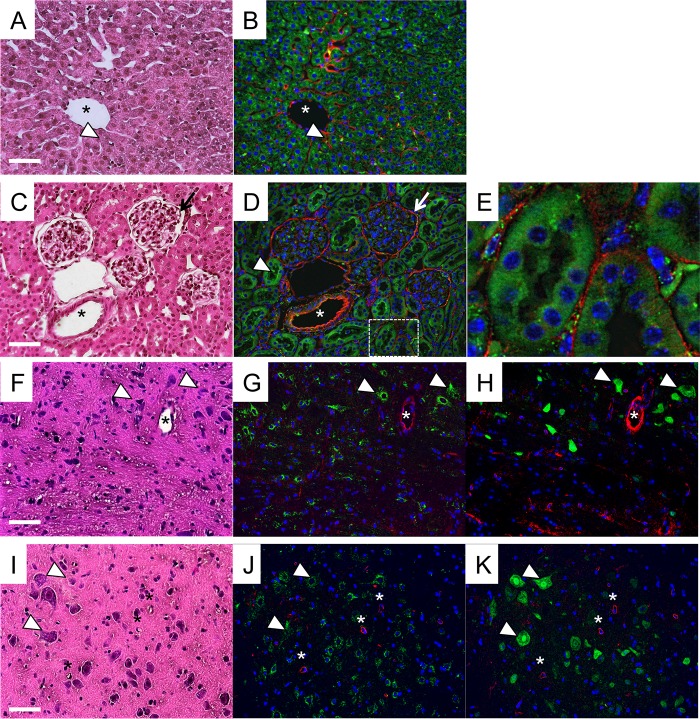

We determined HS expression to see if HS supported EV71 infection in target tissues in vivo. We examined the distributions of HS and hSCARB2 in the livers, kidneys, medulla oblongatas, and spinal cords of hSCARB2 tg mice (Fig. 7). Tissue sections of hSCARB2 tg mice were stained with an anti-HS monoclonal antibody (F58-10E4) and an anti-hSCARB2 antibody. F58-10E4 recognizes N-sulfated glucosamine residues, which are present in many types of HS. We confirmed the specificity of HS staining using an isotype control antibody (data not shown). In all the tissues, HS was strongly expressed in blood vessels, where hSCARB2 expression was undetectable (Fig. 7). In the liver, hSCARB2 was highly expressed in hepatocytes, whereas HS was detected mainly in sinusoidal endothelial cells and vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 7A and B). In the kidney, HS was expressed in the glomerulus and at much lower levels in renal tubules (Fig. 7C and D). In contrast, hSCARB2 was highly expressed in renal tubules and less highly expressed in the glomerulus. In addition, HS was detected on basement membranes surrounding renal tubules (Fig. 7E), indicating that HS was expressed in the extracellular matrix. The endothelial cells and glomerulus, which express hSCARB2 at low or undetectable levels, will not permit EV71 replication but will adsorb VP1-145G viruses. These results suggested that HS is not expressed at high levels in hSCARB2-expressing cells and does not support VP1-145G virus infection in these cells.

FIG 7.

HS expression in hSCARB2 tg mice. Serial tissue sections of livers (A and B), kidneys (C to E), medulla oblongatas in brains (F to H), and spinal cords (I to K) prepared from hSCARB2 tg mice were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (A, C, F, and I), with anti-HS (red), anti-hSCARB2 (green), and DAPI (blue) (B, D, E, G, and J), or with anti-HS (red), anti-NeuN (green), and DAPI (blue) (H and K). Blood vessels are indicated with asterisks. Sinusoidal endothelium (arrowheads in panels A and B), renal tubules (arrowheads in panels C and D), glomeruli (arrows in panels C and D), and neuronal cells (arrowheads in panels F to K) are labeled. The area surrounding the renal tubes marked by a dashed box in panel D is enlarged in panel E. Scale bars indicate 50 μm.

We stained the CNS tissue sections using the anti-HS and anti-SCARB2 antibodies and used anti-NeuN to identify neurons (Fig. 7F to K). The distributions of HS and hSCARB2 expression were clearly different (Fig. 7G and J). HS was highly expressed in the vascular endothelial cells. The cells that expressed HS were not stained with anti-NeuN antibody (Fig. 7H and K). In contrast, observation of immediately adjacent sections of brain and spinal cord suggested that hSCARB2 was expressed predominantly in neuronal cells in the CNS tissue (arrowheads in Fig. 7F to K), consistent with our previous report (21). The data clearly indicated that HS expressed in the CNS would not be able to contribute to VP1-145G virus replication. In this situation, HS binding may be rather disadvantageous for virus replication.

VP1-145G virus is immediately adsorbed to nonsusceptible cells.

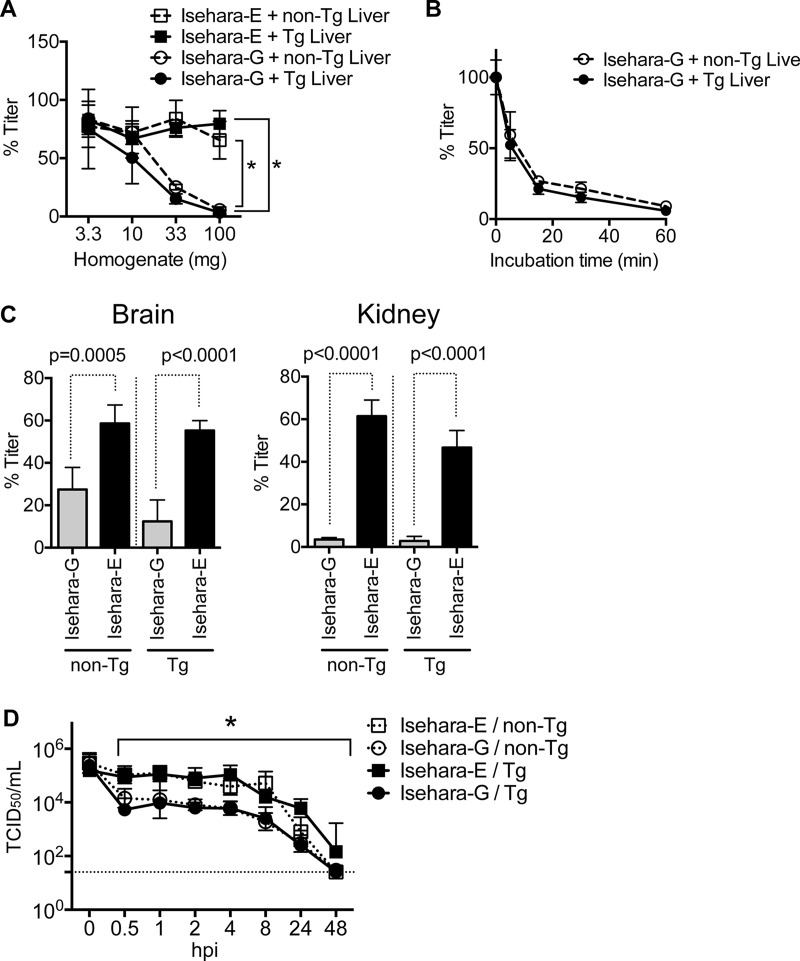

We then hypothesized that the majority of VP1-145G virus might be adsorbed to HS expressed on hSCARB2-negative cells or in the extracellular matrix and that this is why VP1-145G virus was attenuated. To confirm our hypothesis, we first examined whether the virus was able to bind to liver, kidney, and brain homogenate. Either Isehara-G or Isehara-E was mixed with tissue homogenate of hSCARB2 tg and non-tg mice at 37°C for 1 h. After the mixture was centrifuged, the virus titer of the supernatants (unbound viruses) was determined. The virus titer of Isehara-G mixed with liver homogenate prepared from tg and non-tg mice decreased significantly, whereas that of Isehara-E did not (Fig. 8A). Since both viruses are stable during the incubation period (data not shown), the decrease of the virus titer of Isehara-G was not due to inactivation but was due to adsorption to the liver homogenate. Differences between Isehara-G and Isehara-E were significant (by two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]) in the binding to 33 and 100 mg of liver homogenate. Approximately 75% of Isehara-G was bound to the homogenate within 30 min (Fig. 8B). Similar results were obtained using kidney and brain homogenates (Fig. 8C). We observed adsorption of the virus with non-tg tissue homogenate, suggesting that the adsorption of Isehara-G is not due to hSCARB2 but is due to a negatively charged molecule(s), including HS, present in the non-tg mice.

FIG 8.

Isehara-G is immediately adsorbed to nonsusceptible cells. (A to C) Isehara-G is adsorbed to tissue homogenate. Tissue homogenates were prepared from livers, kidneys, and brains harvested from hSCARB2 tg and non-tg mice. (A to C) One thousand PFU of Isehara-G or Isehara-E was incubated with different amounts of liver homogenate at 37°C for 1 h (A), with 100 mg liver homogenate at 37°C for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min (B), or with 100 mg kidney or brain homogenate at 37°C for 1 h (C). After incubation, unbound virus was quantitated using RD-A cells. The data are presented as percentage of input virus. (D) The titer of Isehara-G decreases in the bloodstream immediately after inoculation. hSCARB2 tg and non-tg mice were intravenously inoculated with 106 TCID50 of Isehara-G or Isehara-E. The viremia titer was determined using RD-SCARB2 cells. The dashed line indicates the detection limit. In panel A, asterisks indicate significant differences between Isehara-G and Isehara-E in binding to 33 or 100 mg liver homogenate (two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple-comparison test). In panel C, P values are shown above the graph (t test). In panel D, an asterisk indicates significant differences between Isehara-G and Isehara-E from 0.5 to 48 hpi in hSCARB2 tg mouse and non-tg mouse infection (two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple-comparison test).

Isehara-G or Isehara-E was inoculated intravenously in hSCARB2 tg mice or non-tg mice. The mice were sacrificed after inoculation, and blood was collected. The virus titers in the plasma of hSCARB2 tg mice inoculated with Isehara-E did not decrease until 8 hpi (Fig. 8D). In contrast, the titer of Isehara-G in plasma rapidly decreased within 30 min of infection. The virus titer of Isehara-G was significantly lower than that of Isehara-E at 0.5 to 48 hpi, suggesting that Isehara-G was adsorbed, likely to endothelial cells or peripheral tissues, soon after inoculation. Similar results were obtained when we inoculated non-tg mice. The results suggested that the adsorption was specific to Isehara-G and independent of hSCARB2 expression. An increase in the virus titer in the brain and spinal cord in hSCARB2 tg mice was observed only in the mice inoculated with Isehara-E (Fig. 5E and F), suggesting that the maintenance of viremia titer at a high level is necessary for virus entrance into the CNS.

DISCUSSION

VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses were recovered from infectious cDNA clones after transfection of viral RNA into RD-SCARB2 cells (Fig. 1). Both viruses replicated in RD-A cells and L-SCARB2 cells (Fig. 2). VP1-145G viruses grew better than or as well as VP1-145E viruses in vitro. Neither virus replicated at all in the absence of hSCARB2, suggesting that hSCARB2 is essential for the establishment of infection (Fig. 3). Since hSCARB2 can initiate uncoating of the virion (18), hSCARB2 is critical for this step for both viruses. Viruses including VP1-145G and VP1-145Q are thought to use HS as an attachment receptor (28). To confirm this, we investigated receptor dependency of the VP1-145G and VP1-145E viruses using genetically modified cell lines. The apparent titer of VP1-145G viruses in HS-deficient cells was significantly lower than that in wild-type cells (Fig. 3A). In addition, VP1-145G viruses bound to heparin-agarose beads (Fig. 3B). These results suggested that VP1-145G viruses bind to the cell surface via HS and that this increases their infection efficiency. After binding of the virus on the cell surface, the bound virus may be transferred to hSCARB2. hSCARB2 at the endosome initiates uncoating. The ability of VP1-145G viruses to bind to HS is advantageous because it increases the chances of these viruses binding to the surface of cultured cells, where hSCARB2 is not highly expressed.

However, VP1-145E viruses were more virulent in hSCARB2 tg mice (Fig. 4B). Isehara-E replicated more efficiently than Isehara-G in the CNS and nonneural tissues of hSCARB2 tg mice (Fig. 5). After infection with Isehara-G, a small number of tg mice showed paralysis and death. The viruses recovered from these mice always had a G-to-E amino acid substitution at VP1-145 (Table 1). These results clearly suggested that the ability to use HS is disadvantageous for the virus in vivo. This hypothesis is supported by the distribution of HS (Fig. 7). HS is highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells and some other cell types expressing low or undetectable levels of hSCARB2. As suggested by the results obtained using SCARB2 KO cells (Fig. 3A), infection of vascular endothelial cells may be abortive. We reported previously that some cells expressing the poliovirus receptor in nonneural tissues do not permit poliovirus replication due to the efficient type I interferon response in these cells (31). It is also likely that some HS-positive and SCARB2-positive cells may not permit EV71 replication for the same reason. Together, the results suggest that binding to HS expressed on nonneural cells only serves to decrease the amount of virus circulating in the body.

We examined whether Isehara-G is actually adsorbed and decreased in the bloodstream after intravenous inoculation (Fig. 8D). As expected, the titer circulating in the blood after intravenous inoculation with Isehara-G decreased soon after inoculation, whereas it remained at a high level in mice inoculated with Isehara-E. This adsorption was not due to hSCARB2, because the Isehara-G titer inoculated in non-tg mice also decreased with similar kinetics. One day after infection with Isehara-E, the virus appeared in the CNS of hSCARB2 tg mice, and the virus titer increased on days 2 and 3 (Fig. 5E and F). Isehara-G was also detected in the CNS, but the amount of the virus was much smaller than that of Isehara-E and did not increase thereafter. The adsorption of Isehara-G was also observed when the virus was incubated with liver, kidney, or brain homogenate of hSCARB2 tg mice (Fig. 8A to C). Again, the adsorption by these homogenates from non-tg mice was also observed. It is therefore likely that Isehara-G was specifically adsorbed to HS or other negatively charged molecules. If the virus binds to HS in vivo, it can be easily trapped and prevented from spreading in the body. Therefore, we propose that this is one of the major mechanisms of attenuation of VP1-145G viruses.

If our hypothesis is correct, VP1-145E viruses should be virulent in other animal models. Kataoka et al. compared the virulence of PSGL-1-binding and PSGL-1-nonbinding strains in cynomolgus monkeys (32). They found that the PSGL-1-binding strain, which is also the HS-binding strain, was less virulent than the PSGL-1-nonbinding strain and disappeared soon after inoculation. Instead, the PSGL-1-nonbinding strain was isolated from the monkeys that had been inoculated with the PSGL-1-binding strain. We also found that Isehara-E and C7-E were more virulent than the corresponding VP1-145G strains and that Isehara-E and C7-E were recovered from monkeys that had been inoculated with Isehara-G and C7-G, respectively (33). It is therefore likely that VP1-145E viruses exhibit a virulent phenotype and VP1-145G viruses exhibit an attenuated phenotype in a monkey model. Because HS is expressed in vascular endothelium at high levels and in neuronal cells at low or undetectable levels in nonhuman primate tissues (33), the hypothesis may be applicable to monkey or human infections.

Various studies have previously demonstrated that HS- and GAG-binding viruses may have been attenuated. Lee and Lobigs reported that an HS-binding variant of Japanese encephalitis virus has reduced virulence (34), and based on their results, Tan et al. (28) more recently proposed that virulence of HS-binding variants of EV71 may also be attenuated. In addition, several previous reports demonstrated attenuation of HS- or GAG-binding virus variants belonging to the Flaviviridae (Japanese encephalitis virus, Murray Valley encephalitis virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus) (35–39) and the Togaviridae (Sindbis virus, chikungunya virus, and Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus) (40–45) in an animal infection model. GAG-binding variants were cleared from the blood of infected animals within 30 min after intravenous inoculation (34–36, 45). Similar attenuation of HS- and GAG-binding variants has been reported for picornaviruses. Tissue culture of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and undergo attenuation in cattle (46), and coxsackievirus B3 collected from fecal samples of infected mice acquired a large-plaque phenotype and showed reduced HS binding and enhanced virulence in mice (47). These results strongly suggest that attenuation of HS- and GAG-binding variants occurs in a wide range of viruses.

We have demonstrated that VP1-145 is critical for EV71 neurovirulence in hSCARB2 tg mice. However, it is clear that this is only one of several virulence determinants, since almost all EV71 strains freshly isolated from human patients have VP1-145E. The relationship between virulence in humans and the viral sequence has not been fully elucidated. Using many isolates and hSCARB2 tg mice will help to characterize this relationship.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statements.

Experiments using recombinant DNA and pathogens were approved by the Committee for Experiments using Recombinant DNA and Pathogens at the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science. Experiments using mice were approved by the Animal Use and Care Committee and performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals (Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, 2011).

Preparation of cell lines.

The cells were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 5% fetal calf serum (FCS). Human RD-A cells were kindly provided by Hiroyuki Shimizu, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. L929 cells expressing hSCARB2 (L-SCARB2 cells) were described previously (17).

To establish SCARB2 overexpression cells (RD-SCARB2 cells), human SCARB2 cDNA ligated with a Flag tag was inserted into AgeI and BamHI sites of the pQCIXP vector (Clontech). The recombinant retrovirus was produced by transfecting this plasmid and pVSV-G (Clontech) into GP2-293 cells (Clontech). RD-A cells were infected with the recombinant virus. The RD-SCARB2 cells were selected in medium containing 1 μg/ml puromycin.

SCARB2, EXT1, and EXT2 gene knockout cells were prepared using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. To construct pX458-EXT1, pX458-EXT2, and pX330-SCARB2, pairs of oligonucleotides encoding gene-specific short guide RNAs were synthesized (Fig. 2A). The sequences of synthesized oligonucleotides were as follows: 5′-CAC CGA CCC AGG CAG GAC ACA TGC-3′ and 5′-AAA CGC ATG TGT CCT GCC TGG GTC-3′ for EXT1, 5′-CAC CGC TAT GCT CTG AAA AAG TAC G-3′ and 5′-AAA CCG TAC TTT TTC AGA GCA TAG C-3′ for EXT2, and 5′-CAC CGC TTC AAT GTC ACC AAT CCA G-3′ and 5′-AAA CCT GGA TTG GTG ACA TTG AAG C-3′ for SCARB2. Hybridized oligonucleotides were inserted into the BbsI site of pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP (pX458) or pX330-U6-Chimeric_BB-CBh-hSpCas9 (gifts from Feng Zhang; Addgene plasmids 48138 and 42230, respectively) (48). RD-A cells were transfected with these plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive cells were sorted with a FACS-Aria III (BD Biosciences) at 3 days after transfection and then cloned by limiting dilution. Genomic DNA was prepared from each colony, and the DNA fragment surrounding the target sequence was amplified by PCR using specific primer pairs (5′-AGT CTT TAC AGG CGG GAA GAT G-3′ and 5′-ATC CCA AGG AAC GAA GGG GC-3′ for EXT1, 5′-AAT GTA GAG AAG CGC AGC ATC C-3′ and 5′-GGG CTG TAT GAG TGT GAG ATA CC-3′ for EXT2, and 5′-GTG ATC TAG GAG GTC AGA ATA GGG G-3′ and 5′-CAG CGT TTC AGA CAA TGA AAT CAG-3′ for SCARB2). The targeted sequences for EXT1, EXT2, and SCARB2 contained restriction enzyme sites NlaIII, RsaI, and Hpy188III, respectively. Cells possessing sequences resistant to digestion were selected as candidate gene knockout cells. PCR-amplified genomic regions were cloned into the pGEM-T-Easy vector (Promega) and sequenced (Fig. 2A).

To confirm depletion of hSCARB2, cells were lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). Solubilized proteins were denatured in 2× SDS sample buffer at 90°C for 5 min. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane using Direct blot (Sharp, Osaka, Japan). To detect proteins, anti-SCARB2 antibody (R&D Systems) and anti-β-actin antibody (AC74; Sigma-Aldrich) were used.

To confirm depletion of HS, cell surface expression of HS was detected by flow cytometry. Cells were detached by treatment with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.02% EDTA. Suspended cells were stained with mouse anti-HS monoclonal antibody (1:50 dilution; F58-10E4 [Amsbio]) or isotype control IgM (1:50 dilution; MM-30 [BioLegend]) for 30 min on ice and then stained with Cy3-conjugated anti-IgM antibody (1:200 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 30 min on ice and with propidium iodide (PI) (1:100 dilution). Stained cells were analyzed using LSRFortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences).

Preparation of cDNA clones and their mutants.

An infectious cDNA clone for the SK-EV006 strain (subgenogroup B2; GenBank accession number AB469182.1), pSVA-EV71-SK-EV006 (17), was used. Viral RNAs of the Isehara strain (subgenogroup C2; GenBank accession number LC375764) and the C7/Osaka strain (subgenogroup B4; GenBank accession number LC375765) were prepared using the QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) with random hexamers as primers and the viral RNAs as templates, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cDNA was amplified with 5′ primer NotI-T7-EV-5 (5′-CGG CGG CCG CGT AAT ACG ACT CAC TAT AGG TTA AAA CAG CCT GTG GGT TG-3′) or 3′ primer SalI-dT25 (5′-GCG TCG ACT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT-3′) or XhoI-dT25 (5′-CAC ACT CGA GTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTT TTG CTA TTC TGG-3′) and appropriate primers within the viral genome sequence. Amplification was performed with PfuUltra II Fusion HS DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies Inc.), Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs), or PrimeSTAR GXL DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Bio), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The amplified cDNAs were ligated using appropriate restriction enzyme sites and finally cloned into NotI and SalI sites of the pSVA vector (17). The resulting plasmids were referred to as pSVA-EV71-Isehara and pSVA-EV71-C7/Osaka, respectively. The G-to-A or A-to-G point mutations at amino acid position VP1-145 of the three virus strains were produced by amplifying the fragment using a pair of mutated primers (Isehara-VP1-145G-F, 5′-CCT ACC GGG GGA GTT GTC CCG CAA TT-3′; Isehara-VP1-145G-R, 5′-CGG GAC AAC TCC CCC GGT AGG CGT GC-3′; C7-VP1-145E-F, 5′-CCT ACT GGT GAG GTT GTT CCA CAA-3′; C7-VP1-145E-R, 5′-GTG GAA CAA CCT CAC CAG TAG GAG-3′; SK-VP1-145E-F, 5′-CAC CGG CGA GGT TGT TCC ACA ATT-3′; and SK-VP1-145E-R, 5′-GGA ACA ACC TCG CCG GTG GGA GTG-3′) and appropriate primers. The DNA fragment of the original plasmid was replaced with the corresponding mutated fragment.

The plasmid linearized by SalI or XhoI digestion was subjected to in vitro transcription using the MEGAscript T7 high-yield transcription kit (Invitrogen). The transcribed RNA was transfected into RD-SCARB2 cells using Lipofectamine 2000. The cytopathic effect began to appear the day after transfection. The virus was recovered at 1 or 2 days posttransfection. The recovered virus was directly used for plaque size determination (Fig. 1A and B), susceptibility assay of knockout cells (Fig. 3A), and heparin-agarose binding assay (Fig. 3B). The virus propagated twice in RD-SCARB2 cells was used for other experiments. The sequence of the recovered virus was determined by direct sequencing, and it was confirmed that the sequence was identical to that of the original plasmid DNA.

Virus titration.

The virus titer was determined by microplate assay using Vero cells, RD-A cells, or RD-SCARB2 cells and was represented as the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50). Briefly, 104 cells were seeded on 96-well plates, and the serially diluted virus was added on the next day. The appearance of the cytopathic effect was monitored by microscopic observation. At 9 days postinfection, the cells were fixed with 10% formalin and stained with crystal violet. The TCID50 was calculated by the method of Kaerber (49). In some cases, the virus titer was determined by a plaque assay on RD-A cells. RD-A cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 6 × 105 cells/well. The serially diluted virus solution was inoculated at 37°C for 1 h. After removal of the virus solution, minimum essential medium containing 5% FCS and 1.2% methylcellulose was overlaid. The cells were incubated for 2 to 5 days until the plaques became visible.

Heparin-agarose binding assay.

The heparin binding assay was performed as previously described with some modifications (28). Briefly, viruses (6 × 106 RNA copies) were incubated with 200 μl heparin-agarose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 1 h. The beads were washed with binding buffer (0.02 M Tris [pH 7.5], 0.14 M NaCl) five times. Bound viruses were incubated with elution buffer (0.02 M Tris [pH 7.5] and 2 M NaCl) at room temperature for 10 min, and eluted viruses were collected. Viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen), followed by reverse transcription using PrimeScript RT master mix (TaKaRa). Quantitative PCR was conducted using enterovirus universal primer pairs (50), SYBR Select master mix (Applied Biosystems), and LightCycler 480-II (Roche Life Science).

Animal experiments for evaluating viral virulence.

Six-week-old hSCARB2 tg mice (21) were used for infection experiments. After anesthetization by inhalation of isoflurane, a total of 200 μl virus solution was inoculated intravenously into the orbital sinus, or 25 μl virus solution was inoculated intracerebrally as previously described (21). The body weight and clinical signs of mice were observed for 2 or 3 weeks.

Pregnant ICR mice were purchased from Clea (Japan). The newborn mice were infected intraperitoneally with 25 μl virus solution within 24 h after birth. Survival of the newborn mice was observed for 2 weeks.

To quantitate the virus titer in infected mouse tissues, we harvested blood, liver, spleen, kidney, brain, and spinal cord specimens under anesthesia. Tissues were homogenized in 10 volumes of DMEM containing 5% FCS using Shake Master (BioMedical Sciences, Japan). After centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, virus titers in supernatants were determined by microplate assay using RD-SCARB2.

Virus adsorption assay in tissue homogenates.

Mouse livers, kidneys, and brains were harvested from hSCARB2 tg and non-tg mice and homogenized in 10 volumes of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.35). The insoluble fraction was washed three times and preserved at −80°C until use. Homogenates were incubated with 1,000 PFU of Isehara-G or Isehara-E virus at 37°C. After centrifugation, supernatants were collected and subjected to plaque assays to determine virus titers.

Virus adsorption assay in vivo.

Isehara-G or Isehara-E virus (1 × 106 TCID50/100 μl) was inoculated into 7-week-old hSCARB2 tg and non-tg mice intravenously. Six mice were sacrificed at each time point from 0.5 to 48 hpi. Whole blood was collected from the heart under anesthesia. Acid-citrate-dextrose solution (100 μl) was added to collected blood as an anticoagulant. Virus titers were determined by microplate assay using RD-A cells.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded sections of hSCARB2 tg mice were stained to evaluate the distribution of HS, hSCARB2, and neuronal markers. Following the retrieval reaction at 121°C for 10 min in a 10 mM sodium citrate solution at pH 6.0, slides were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS at room temperature for 1 h. A rabbit anti-SCARB2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich; 1:200 dilution), mouse IgM anti-HS antibody F58-10E4 (Amsbio; 1:200 dilution), isotype control IgM MM-30 (BioLegend; 1:200 dilution), and/or a rabbit anti-NeuN antibody (Abcam; 1:1,000 dilution) was incubated with the sections overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes; 1:500 dilution) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch; 1:500 dilution) and were incubated with the sections for 1 h at 37°C °C. The sections were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector Laboratories), and images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (BZ-X700; Keyence).

Statistical analyses.

GraphPad Prism version 6.0f for MAC (GraphPad Software) was used for the analysis of statistical significance. In the time course or dose dependency experiments, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak's multiple-comparison test was used to evaluate significant differences between two or more groups (Fig. 1C and 8A, B, and D). For the survival curve data, a log rank test was used (Fig. 4 and 6). For Fig. 3A, a one-sided unpaired t test was used to evaluate significant differences between an experimental group and a control group. In other experiments, a two-sided unpaired t test was used (Fig. 1B, 3B, 5, and 8C).

Accession number(s).

Sequences for the Isehara and C7/0saka strains are available in GenBank under accession numbers LC375764 and LC375765, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kosuke Tanegashima (Stem Cell Project, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) for helpful advice for preparation of knockout cells. We thank Kazuhiko Watabe (Faculty of Medicine, Kyorin University) and Noriyo Nagata (National Institute of Infectious Diseases) for helpful advice for histological examinations. We thank Hiroyuki Shimizu (National Institute of Infectious Diseases) and Junjiro Horiuchi (Learning and Memory Project, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science) for critical readings of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP23390116), by MEXT KAKENHI (grant number JP24115006), and by AMED (grant number JP15fk0108009).

REFERENCES

- 1.Pallansch M, Oberste MS, Whitton JL. 2013. Enteroviruses: polioviruses, coxackieviruses, echoviruses, and newer enteroviruses, p 490–530. In Knipe D, Howley PM (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan LG, Parashar UD, Lye MS, Ong FG, Zaki SR, Alexander JP, Ho KK, Han LL, Pallansch MA, Suleiman AB, Jegathesan M, Anderson LJ, for the Outbreak Study Group. 2000. Deaths of children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Sarawak, Malaysia: clinical and pathological characteristics of the disease. Clin Infect Dis 31:678–683. doi: 10.1086/314032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khanh TH, Sabanathan S, Thanh TT, Thoa le PK, Thuong TC, Hang V, Farrar J, Hien TT, Chau N, van Doorn HR. 2012. Enterovirus 71-associated hand, foot, and mouth disease, southern Vietnam, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis 18:2002–2005. doi: 10.3201/eid1812.120929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho M, Chen ER, Hsu KH, Twu SJ, Chen KT, Tsai SF, Wang JR, Shih SR. 1999. An epidemic of enterovirus 71 infection in Taiwan. Taiwan Enterovirus Epidemic Working Group. N Engl J Med 341:929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Yang W, Ren J, Tan X, Wang Y, Mao N, Xu S, Zhu S, Cui A, Yan D, Li Q, Dong X, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Wan J, Feng Z, Sun J, Wang S, Li D, Xu W. 2010. An emerging recombinant human enterovirus 71 responsible for the 2008 outbreak of hand foot and mouth disease in Fuyang city of China. Virol J 7:94. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-7-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen KT, Chang HL, Wang ST, Cheng YT, Yang JY. 2007. Epidemiologic features of hand-foot-mouth disease and herpangina caused by enterovirus 71 in Taiwan, 1998-2005. Pediatrics 120:e244–252. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arita M, Ami Y, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2008. Cooperative effect of the attenuation determinants derived from poliovirus Sabin 1 strain is essential for attenuation of enterovirus 71 in the NOD/SCID mouse infection model. J Virol 82:1787–1797. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01798-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SW, Wang YF, Yu CK, Su IJ, Wang JR. 2012. Mutations in VP2 and VP1 capsid proteins increase infectivity and mouse lethality of enterovirus 71 by virus binding and RNA accumulation enhancement. Virology 422:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaini Z, McMinn P. 2012. A single mutation in capsid protein VP1 (Q145E) of a genogroup C4 strain of human enterovirus 71 generates a mouse-virulent phenotype. J Gen Virol 93:1935–1940. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043893-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang YF, Chou CT, Lei HY, Liu CC, Wang SM, Yan JJ, Su IJ, Wang JR, Yeh TM, Chen SH, Yu CK. 2004. A mouse-adapted enterovirus 71 strain causes neurological disease in mice after oral infection. J Virol 78:7916–7924. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.7916-7924.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chua BH, Phuektes P, Sanders SA, Nicholls PK, McMinn PC. 2008. The molecular basis of mouse adaptation by human enterovirus 71. J Gen Virol 89:1622–1632. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83676-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Fu C, Wu S, Chen X, Shi Y, Zhou B, Zhang L, Zhang F, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Fan C, Han S, Yin J, Peng B, Liu W, He X. 2014. A novel finding for enterovirus virulence from the capsid protein VP1 of EV71 circulating in mainland China. Virus Genes 48:260–272. doi: 10.1007/s11262-014-1035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B, Wu X, Huang K, Li L, Zheng L, Wan C, He ML, Zhao W. 2014. The variations of VP1 protein might be associated with nervous system symptoms caused by enterovirus 71 infection. BMC Infect Dis 14:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Zou Q, Chen L, Zhang H, Wang Y. 2011. Molecular analysis of virulent determinants of enterovirus 71. PLoS One 6:e26237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang SC, Li WC, Chen GW, Tsao KC, Huang CG, Huang YC, Chiu CH, Kuo CY, Tsai KN, Shih SR, Lin TY. 2012. Genetic characterization of enterovirus 71 isolated from patients with severe disease by comparative analysis of complete genomes. J Med Virol 84:931–939. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuta K, Abiko C, Murata T, Matsuzaki Y, Itagaki T, Sanjoh K, Sakamoto M, Hongo S, Murayama S, Hayasaka K. 2005. Frequent importation of enterovirus 71 from surrounding countries into the local community of Yamagata, Japan, between 1998 and 2003. J Clin Microbiol 43:6171–6175. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6171-6175.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamayoshi S, Yamashita Y, Li J, Hanagata N, Minowa T, Takemura T, Koike S. 2009. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:798–801. doi: 10.1038/nm.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamayoshi S, Ohka S, Fujii K, Koike S. 2013. Functional comparison of SCARB2 and PSGL1 as receptors for enterovirus 71. J Virol 87:3335–3347. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02070-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamayoshi S, Iizuka S, Yamashita T, Minagawa H, Mizuta K, Okamoto M, Nishimura H, Sanjoh K, Katsushima N, Itagaki T, Nagai Y, Fujii K, Koike S. 2012. Human SCARB2-dependent infection by coxsackievirus A7, A14, and A16 and enterovirus 71. J Virol 86:5686–5696. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00020-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He Y, Ong KC, Gao Z, Zhao X, Anderson VM, McNutt MA, Wong KT, Lu M. 2014. Tonsillar crypt epithelium is an important extra-central nervous system site for viral replication in EV71 encephalomyelitis. Am J Pathol 184:714–720. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujii K, Nagata N, Sato Y, Ong KC, Wong KT, Yamayoshi S, Shimanuki M, Shitara H, Taya C, Koike S. 2013. Transgenic mouse model for the study of enterovirus 71 neuropathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:14753–14758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217563110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura Y, Shimojima M, Tano Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Shimizu H. 2009. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med 15:794–797. doi: 10.1038/nm.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan CW, Poh CL, Sam IC, Chan YF. 2013. Enterovirus 71 uses cell surface heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan as an attachment receptor. J Virol 87:611–620. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02226-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang SL, Chou YT, Wu CN, Ho MS. 2011. Annexin II binds to capsid protein VP1 of enterovirus 71 and enhances viral infectivity. J Virol 85:11809–11820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Su PY, Liu YT, Chang HY, Huang SW, Wang YF, Yu CK, Wang JR, Chang CF. 2012. Cell surface sialylation affects binding of enterovirus 71 to rhabdomyosarcoma and neuroblastoma cells. BMC Microbiol 12:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su PY, Wang YF, Huang SW, Lo YC, Wang YH, Wu SR, Shieh DB, Chen SH, Wang JR, Lai MD, Chang CF. 2015. Cell surface nucleolin facilitates enterovirus 71 binding and infection. J Virol 89:4527–4538. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03498-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Du N, Cong H, Tian H, Zhang H, Zhang W, Song L, Tien P. 2014. Cell surface vimentin is an attachment receptor for enterovirus 71. J Virol 88:5816–5833. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03826-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tan CW, Sam IC, Lee VS, Wong HV, Chan YF. 2017. VP1 residues around the five-fold axis of enterovirus A71 mediate heparan sulfate interaction. Virology 501:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishimura Y, Lee H, Hafenstein S, Kataoka C, Wakita T, Bergelson JM, Shimizu H. 2013. Enterovirus 71 binding to PSGL-1 on leukocytes: VP1-145 acts as a molecular switch to control receptor interaction. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003511. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. 2011. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3:a004952. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ida-Hosonuma M, Iwasaki T, Yoshikawa T, Nagata N, Sato Y, Sata T, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Taya C, Yonekawa H, Koike S. 2005. The alpha/beta interferon response controls tissue tropism and pathogenicity of poliovirus. J Virol 79:4460–4469. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4460-4469.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kataoka C, Suzuki T, Kotani O, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Nagata N, Ami Y, Wakita T, Nishimura Y, Shimizu H. 2015. The role of VP1 amino acid residue 145 of enterovirus 71 in viral fitness and pathogenesis in a cynomolgus monkey model. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005033. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujii K, Sudaka Y, Takashino A, Kobayashi K, Kataoka C, Suzuki T, Iwata-Yoshikawa N, Konani O, Ami Y, Shimizu H, Nagata N, Mizuta K, Matsuzaki Y, Koike S. 2018. VP1 amino acid residue 145 of enterovirus 71 is a key residue for its receptor attachment and resistance to neutralizing antibody during cynomolgus monkey infection. J Virol 92:e00682-. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00682-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee E, Lobigs M. 2002. Mechanism of virulence attenuation of glycosaminoglycan-binding variants of Japanese encephalitis virus and Murray Valley encephalitis virus. J Virol 76:4901–4911. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4901-4911.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee E, Hall RA, Lobigs M. 2004. Common E protein determinants for attenuation of glycosaminoglycan-binding variants of Japanese encephalitis and West Nile viruses. J Virol 78:8271–8280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8271-8280.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee E, Wright PJ, Davidson A, Lobigs M. 2006. Virulence attenuation of dengue virus due to augmented glycosaminoglycan-binding affinity and restriction in extraneural dissemination. J Gen Virol 87:2791–2801. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anez G, Men R, Eckels KH, Lai CJ. 2009. Passage of dengue virus type 4 vaccine candidates in fetal rhesus lung cells selects heparin-sensitive variants that result in loss of infectivity and immunogenicity in rhesus macaques. J Virol 83:10384–10394. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01083-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nickells J, Cannella M, Droll DA, Liang Y, Wold WS, Chambers TJ. 2008. Neuroadapted yellow fever virus strain 17D: a charged locus in domain III of the E protein governs heparin binding activity and neuroinvasiveness in the SCID mouse model. J Virol 82:12510–12519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00458-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandl CW, Kroschewski H, Allison SL, Kofler R, Holzmann H, Meixner T, Heinz FX. 2001. Adaptation of tick-borne encephalitis virus to BHK-21 cells results in the formation of multiple heparan sulfate binding sites in the envelope protein and attenuation in vivo. J Virol 75:5627–5637. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5627-5637.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klimstra WB, Ryman KD, Johnston RE. 1998. Adaptation of Sindbis virus to BHK cells selects for use of heparan sulfate as an attachment receptor. J Virol 72:7357–7366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryman KD, Klimstra WB, Johnston RE. 2004. Attenuation of Sindbis virus variants incorporating uncleaved PE2 glycoprotein is correlated with attachment to cell-surface heparan sulfate. Virology 322:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gardner CL, Hritz J, Sun C, Vanlandingham DL, Song TY, Ghedin E, Higgs S, Klimstra WB, Ryman KD. 2014. Deliberate attenuation of chikungunya virus by adaptation to heparan sulfate-dependent infectivity: a model for rational arboviral vaccine design. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e2719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashbrook AW, Burrack KS, Silva LA, Montgomery SA, Heise MT, Morrison TE, Dermody TS. 2014. Residue 82 of the chikungunya virus E2 attachment protein modulates viral dissemination and arthritis in mice. J Virol 88:12180–12192. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01672-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silva LA, Khomandiak S, Ashbrook AW, Weller R, Heise MT, Morrison TE, Dermody TS. 2014. A single-amino-acid polymorphism in chikungunya virus E2 glycoprotein influences glycosaminoglycan utilization. J Virol 88:2385–2397. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03116-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernard KA, Klimstra WB, Johnston RE. 2000. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus confer heparan sulfate interaction, low morbidity, and rapid clearance from blood of mice. Virology 276:93–103. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sa-Carvalho D, Rieder E, Baxt B, Rodarte R, Tanuri A, Mason PW. 1997. Tissue culture adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and are attenuated in cattle. J Virol 71:5115–5123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Pfeiffer JK. 2016. Emergence of a large-plaque variant in mice Infected with coxsackievirus B3. mBio 7:e00119. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00119-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. 2013. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kärber G. 1931. Beitrag zur kollektiven Behandlung pharmakologischer Reihenversuche. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol 162:480–483. doi: 10.1007/BF01863914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jonsson N, Gullberg M, Lindberg AM. 2009. Real-time polymerase chain reaction as a rapid and efficient alternative to estimation of picornavirus titers by tissue culture infectious dose 50% or plaque forming units. Microbiol Immunol 53:149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]