ABSTRACT

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), a virulent pathogen of swine, suppresses the innate immune response and induces persistent infection. One mechanism used by viruses to evade the immune system is to cripple the antigen-processing machinery in monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs). In this study, we show that MoDCs infected by PRRSV express lower levels of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-peptide complex proteins TAP1 and ERp57 and are impaired in their ability to stimulate T cell proliferation and increase their production of CD83. Neutralization of sCD83 removes the inhibitory effects of PRRSV on MoDCs. When MoDCs are incubated with exogenously added sCD83 protein, TAP1 and ERp57 expression decreases and T lymphocyte activation is impaired. PRRSV nonstructural protein 1α (Nsp1α) enhances CD83 promoter activity. Mutations in the ZF domain of Nsp1α abolish its ability to activate the CD83 promoter. We generated recombinant PRRSVs with mutations in Nsp1α and the corresponding repaired PRRSVs. Viruses with Nsp1α mutations did not decrease levels of TAP1 and ERp57, impair the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cell proliferation, or increase levels of sCD83. We show that the ZF domain of Nsp1α stimulates the secretion of CD83, which in turn inhibits MoDC function. Our study provides new insights into the mechanisms of immune suppression by PRRSV.

IMPORTANCE PRRSV has a severe impact on the swine industry throughout the world. Understanding the mechanisms by which PRRSV infection suppresses the immune system is essential for a robust and sustainable swine industry. Here, we demonstrated that PRRSV infection manipulates MoDCs by interfering with their ability to produce proteins in the MHC-peptide complex. The virus also impairs the ability of MoDCs to stimulate cell proliferation, due in large part to the enhanced release of soluble CD83 from PRRSV-infected MoDCs. The viral nonstructural protein 1 (Nsp1) is responsible for upregulating CD83 promoter activity. Amino acids in the ZF domain of Nsp1α (L5-2A, rG45A, G48A, and L61-6A) are essential for CD83 promoter activation. Viruses with mutations at these sites no longer inhibit MoDC-mediated T cell proliferation. These findings provide novel insights into the mechanism by which the adaptive immune response is suppressed during PRRSV infection.

KEYWORDS: Erp57, MoDC, Nsp1α, TAP1, porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, sCD83

INTRODUCTION

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) is a highly infectious disease that causes severe losses in the swine industry throughout the world. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV), the etiologic agent, is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Arteriviridae family (1, 2). The viral genome has nine open reading frames that encode seven structural proteins and 16 nonstructural proteins; all play essential roles in diverse processes related to pathogenesis, such as replication, infection, and virulence (1, 3).

PRRSV suppresses the host immune system by negatively regulating adaptive immunity. Immunosuppression is the result of several factors, including the perturbation of monocyte/macrophage cell development, a reduction in antiviral and inflammatory cytokines, and an increased secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines (3–8). PRRSV infection negatively affects expression of MHC and costimulation in monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs), thereby suppressing B, T, and NK cell proliferation and differentiation (3, 7). Nsp1β in the type 2 PRRSV isolate SD95-21 inhibits interferon (IFN) production by restraining double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-mediated IRF3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation (4). The N protein of PRRSV strain BB0907 is involved in IL-10 induction, which stimulates the development of Tregs and weakens T cell proliferation in the host (9, 10). Nsp1α and Nsp1β in PRRSV strain FL12 are involved in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) suppression via NF-κB and Sp1 elements (11, 12).

Nsp1 is the first viral protein synthesized during PRRSV infection and is autocleaved to yield Nsp1α and Nsp1β. Nsp1α contains an amino-terminal zinc finger (ZF) domain, a papain-like cysteine protease domain, and a C-terminal extension (CTE) (11, 13–16). Two zinc ions associate with the Nsp1α subunit. The spatial conformation of one of the ions is maintained by Cys8, Cys10, Cys25, and Cys28 in the ZF domain, while the other ion is tetrahedrally coordinated with Cys70, Cys76, and His146 in the papain-like cysteine protease (PCP) α domain (15–17). The ability of Nsp1α to inhibit the expression of beta interferon (IFN-β) is blocked by mutations at any of these Cys residues, suggesting that the inhibitory effect depends on their ability to maintain Nsp1α conformation (17). PRRSV suppresses TNF-α expression both in vitro and in vivo via Nsp1α and Nsp1β (11, 12). These two proteins also suppress IFN-β production via IRF3, NF-κB-mediated IFN gene induction, and the JAK-STAT pathway (14, 16, 18–20). Nsp1α is therefore an important multifunctional protein that negatively modulates innate immunity, possibly as a key actor in PRRSV immune escape.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are antigen-presenting cells in the immune system and play a critical role in regulating both innate and adaptive immunity. DCs continuously monitor their environment for potential antigens and present them to T cells to induce an effector immune response or tolerance (21–24). During viral infection, MoDCs change cytokine secretion levels and alter the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins and costimulatory molecules on the cell surface (25, 26). The MHC has a critical role in the immune response against viral infections, as MHC class I (MHC-I) molecules function in antigen presentation on the cell surface for T cell recognition (27–29). The MHC class I complex consists of three main subunit structures, which together enable the escape of immune proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cell surface. The complex includes the ATP-binding cassette transporter (TAP), ERp57, and MHC class I molecules (30–32). TAP belongs to a large family of ATP-binding cassette transporters and is composed of the TAP1 and TAP2 subunits (33). It facilitates peptide loading and enhances peptide binding in the ER prior to encountering a class I molecule. TAP also maximizes substrate diversity and affinity. Interestingly, TAP expression or function is directly affected in certain genetic diseases and is targeted by viruses and by tumor cells to disable immune surveillance (31, 34). ERp57, a member of the protein disulfide isomerase family, has been widely studied for its prominent multifunctional role in the immune system at multiple cellular locations outside the ER (35) and is involved in numerous biological functions crucial to human health (36–38). ERp57 participates in the correct folding and in the quality control of newly synthesized glycoproteins. Additionally, it functions in the assembly of the peptide loading complex of MHC class I molecules by catalyzing disulfide formation in the MHC class I heavy chains in the early stages (39–41).

CD83 belongs to the Ig superfamily and is a characteristic cell surface marker for activated dendritic cells (DCs) (42). However, CD83 is expressed on the surface of other cells, including activated T cells, B cells, and NK cells, both in vivo and in vitro (43, 44). CD83 is upregulated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), TNF-α, and CD40L (45, 46). CD83 has also been found in a soluble form (sCD83) that is likely generated by shedding of the membrane CD83 (mCD83) isoform (47). In contrast with mCD83, sCD83 interferes with DC maturation and affects the cellular cytoskeleton. sCD83 decreases mCD83 surface expression when present during maturation of DC cells and reduces DC-mediated T cell stimulation in vitro (48, 49). Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection increases shedding of mCD83 in human DCs; the resulting sCD83 suppresses allogeneic T cell proliferation (50, 51). Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLVI) Tax protein upregulates both mCD83 and sCD83 via the NF-κB signal pathway, which suppress immune responses, including T cell proliferation and survival (52).

Since Nsp1α negatively modulates the immune response and sCD83 plays a critical role in DC activation, we investigated these two factors and their effects on the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cell proliferation. We found that infection with the wild-type PRRSV BB0907 strain inhibits the expression of the MHC-I complex proteins TAP1 and ERp57. Supernatants collected from PRRSV-infected monocytes significantly suppress CD3+ T-cell proliferation. The inhibitory factor was identified as sCD83, which was demonstrated to inhibit TAP1 and ERp57 expression and disturb MoDC-mediated T-cell proliferation. PRRSV Nsp1α stimulates the CD83 promoter. Amino acids L5, D6, G45, G48, L61, P62, R63, F65, and P66 of Nsp1α play critical roles in inducing CD83 production. Thus, the ability of PRRSV to inhibit expression of TAP1 and ERp57, and the ability of MoDCs to stimulate the proliferation of T cells, is largely attributable to the Nsp1α-mediated increase in soluble CD83 that accompanies viral infection.

RESULTS

PRRSV inhibits TAP1 and ERp57 expression and induces CD83 production in MoDCs.

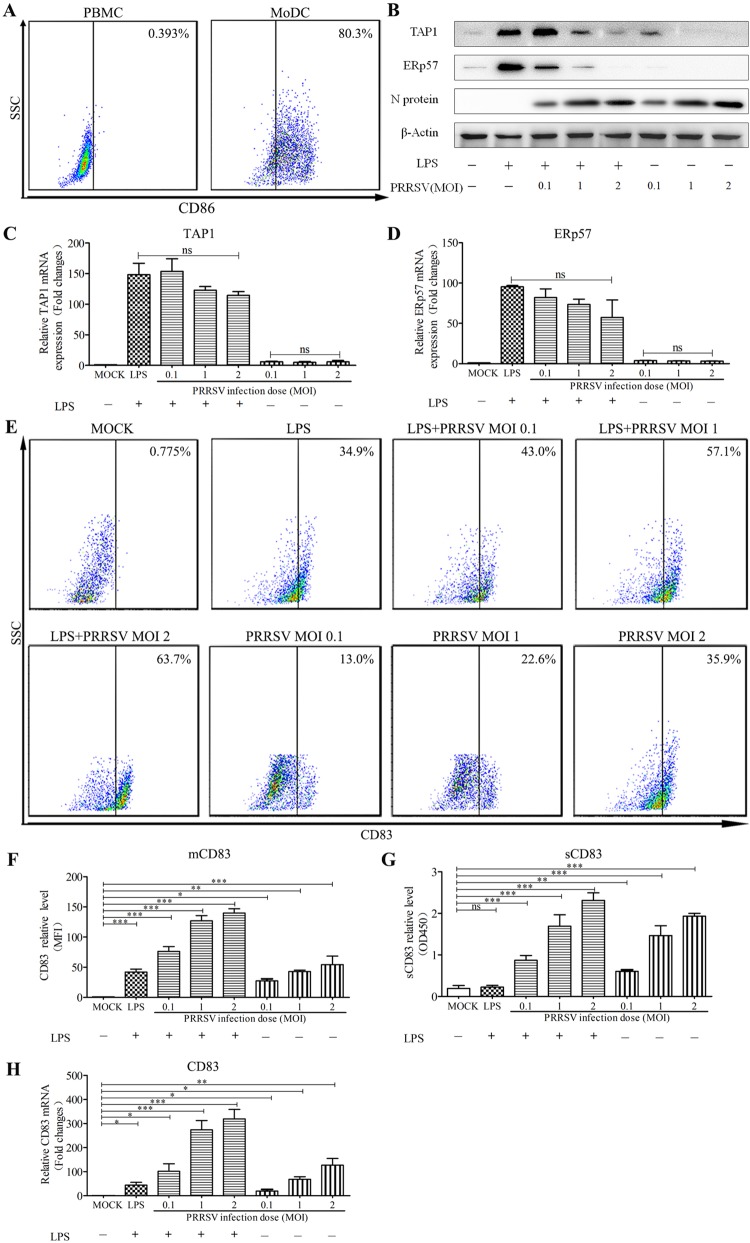

To generate porcine MoDCs, peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) were cultured for 7 days in RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin-4 (IL-4). The MoDCs were then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. A total of 80.3% of the cells exhibited CD86 on the cell surface, indicating a high number of differentiated MoDCs (Fig. 1A). To determine whether PRRSV infection reduces levels of TAP1 and ERp57, MoDCs were incubated with PRRSV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0, 0.1, 1, or 2 in the presence of 10 μg/ml LPS for 24 h. Western blotting showed that PRRSV inhibits production of TAP1 and ERp57 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). However, mRNA levels for TAP1 and ERp57 were not significantly altered by PRRSV infection (Fig. 1C and D). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis revealed that both PRRSV and LPS induced the expression of mCD83 either by themselves or in combination (Fig. 1E and F). PRRSV also significantly increased sCD83 levels in supernatants from MoDCs in a dose-dependent fashion. In contrast, LPS had no effect on sCD83 levels (Fig. 1G). Finally, PRRSV significantly induced the expression of CD83 mRNA, as determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 1H). These results indicate that PRRSV suppresses expression of MHC-peptide complex components TAP1 and ERp57, increases production of CD83, and stimulates the release of sCD83 by MoDCs.

FIG 1.

PRRSV downregulates TAP1 and ERp57 and upregulates CD83 in MoDCs. (A) Porcine monocytes (PMBCs) were cultured for 0 days (left) and 7 days (right) in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4. After staining with an isotype-matched control antibody, the cells were analyzed for CD86 expression at the cell surface using FACS. (B) MoDCs were infected with PRRSV at an MOI of 0.1, 1, and 2 in the presence or absence of LPS (10 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for TAP1, ERp57, and N proteins using Western blotting. β-Actin served as a loading control. TAP1 (C) and ERp57 (D) mRNA levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. mRNA levels were calculated relative to known amounts of template and normalized to β-actin expression. (E) The cells were also analyzed for surface CD83 (mCD83) expression by flow cytometric analysis. (F) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was quantified as a measure of mCD83 production for each analyzed sample. Culture supernatants were also collected, and sCD83 expression was analyzed by ELISA (G) and qRT-PCR (H). MoDCs were inoculated with PRRSV (MOI of 1) at 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, and 48 hpi. All assays were repeated at least three times, with each experiment performed in triplicate. Bars represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

sCD83 inhibits TAP1 and ERp57 expression in MoDCs.

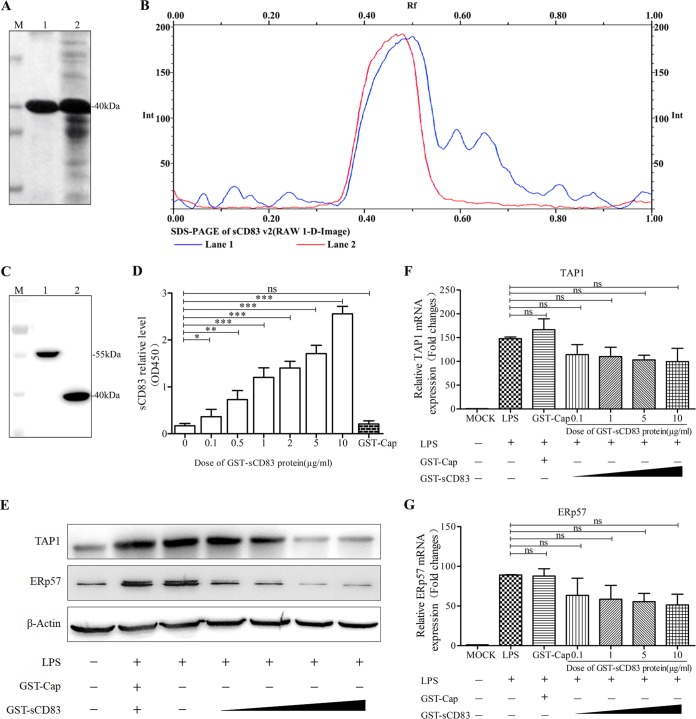

To obtain purified sCD83 protein, the sCD83 coding sequence was cloned into the expression vector pGEX-6P-1 and expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) after induction with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). A 40-kDa soluble fusion protein (glutathione S-transferase [GST]-sCD83) was purified using GST affinity columns and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2A). Gel filtration chromatography analysis confirmed that the purity of the GST-sCD83 exceeded 98% (Fig. 2B). As expected, purified GST-sCD83 protein reacted with anti-CD83 antibody, but purified GST-Cap protein (55 kDa) did not (Fig. 2C and D). GST-Cap was therefore used as a negative control in our experiments.

FIG 2.

Recombinant sCD83 inhibits the expression of TAP1 and ERp57 in MoDCs. (A) Protein electrophoresis showing GST-sCD83 expression and purification. M, protein markers. Lane 1, GST-sCD83 after purification by GST affinity columns; lane 2, soluble component of induced BL21(DE3) with recombinant plasmid pGEX-6P-1/sCD83. (B) Optical scan of thin-layer gel (SDS-PAGE) before (lane 1) and after (lane 2) GST-sCD83 purification. (C) GST-Cap, which was purified in the same way as GST-sCD83, was used as a control. GST-Cap fusion protein and GST-sCD83 fusion protein were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. M, protein markers; lane 1, GST-Cap fusion protein; lane 2, GST-sCD83 fusion protein. (D) Sandwich ELISA analysis demonstrating that GST-sCD83 protein reacts with anti-CD83 antibody. GST-sCD83 protein was used at 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 μg/ml. GST-Cap (5 μg/ml) was used as a negative control. (E) Effect of sCD83 protein on TAP1 and ERp57 expression in MoDCs. MoDCs (1.0 × 106) were incubated with 10 μg/ml LPS and 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml of sCD83 protein for 24 h. Cell lysates were examined by Western blotting with anti-TAP1 and anti-ERp57 antibodies. PBS treatment and GST-Cap (5 μg/ml) were used as negative controls, and endogenous β-actin expression was used as an internal control. TAP1 (F) and ERp57 (G) mRNA expression was analyzed by qRT-PCR. mRNA levels were calculated relative to known amounts of template and normalized to β-actin expression. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

To detect whether sCD83 decreases the expression of TAP1 and ERp57, MoDCs were stimulated by LPS (10 μg/ml) for 24 h in the presence of GST-sCD83 protein at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml, and expression was then measured by Western blotting and qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 2E, levels of TAP1 and ERp57 protein were reduced in cells treated with GST-sCD83 fusion protein at 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml compared with expression in cells treated with GST-Cap (5 μg/ml). However, both TAP1 and ERp57 mRNAs were unaffected significantly by GST-sCD83 (Fig. 2F and G).

Anti-CD83 restores TAP1 and ERp57 expression in PRRSV-infected MoDCs.

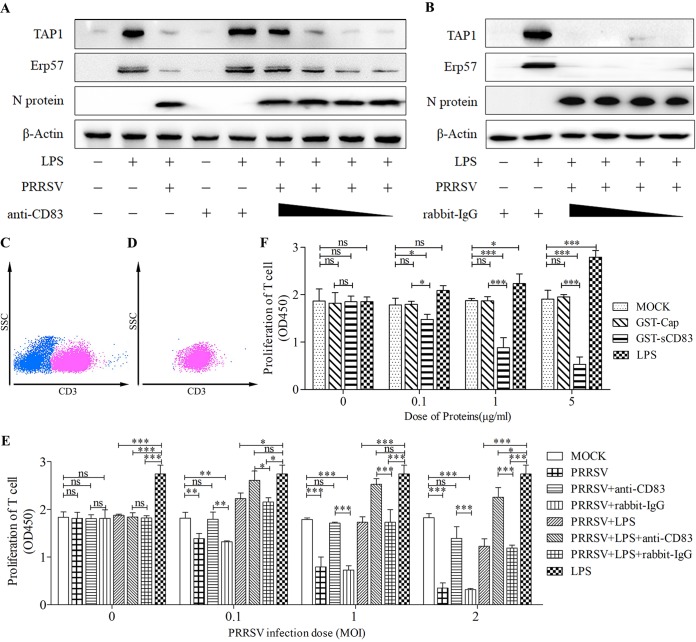

To test if TAP1 and ERp57 expression responds to sCD83 levels, MoDCs were incubated with rabbit anti-CD83 antibody at 20, 2, 1, and 0.4 μg/ml for 1 h and then infected with PRRSV at an MOI of 1 in the presence of LPS at 10 μg/ml. As shown in Fig. 3A, TAP1 and ERp57 levels in cells incubated with rabbit anti-CD83 antibody were higher than those in untreated cells. In contrast, pretreatment of MoDCs with isotype (rabbit IgG at 20, 2, 1, and 0.4 μg/ml) had no effect (Fig. 3B). This result demonstrates that immunodepletion of soluble CD83 largely restores expression of TAP1 and ERp57 in MoDCs.

FIG 3.

Anti-CD83 antibody blocks the ability of PRRSV to depress immunoregulatory activity of MoDCs. (A and B) MoDCs were pretreated with rabbit anti-CD83 antibody (A) to remove sCD83, or with isotype (rabbit IgG) antibody (B) as a negative control, at 20, 2, 1, and 0. 4 μg/ml in the cell culture medium. MoDCs were then infected with PRRSV at an MOI of 1 in the presence of LPS (10 μg/ml) for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for TAP1, ERp57, and N proteins using Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Treatment with LPS (10 μg/ml) alone served as a positive control. (C) T cells are characterized by high CD3 expression. Approximately 50% of freshly isolated PBMCs are T cells. The panel shows a representative dot plot of the flow cytometry gating strategy for T cell selection, using side scatter (SSC) and CD3. (D) Sorting by FACS yields a highly enriched T cell population (98%). Shown is a representative dot plot for enriched CD3+ T lymphocytes. (E) MoDCs were either left untreated or pretreated with anti-CD83 antibody (20 μg/ml) or isotype (20 μg/ml) and infected with PRRSV at an MOI of 0.1, 1, and 2 in the presence or absence of LPS (10 μg/ml). After 24 h, supernatants from these cultures were added to allogeneic T cells. Treatment with LPS alone at 10 μg/ml served as a positive control. T cell proliferation was restored when supernatants were added from PRRSV-infected MoDCs pretreated with rabbit anti-CD83 antibody compared with those pretreated with isotype (20 μg/ml). (F) MoDCs were stimulated with recombinant GST-sCD83 at 0, 0.1, 1, and 5 μg/ml for 24 h. Cell-free supernatants were then transferred to cultures containing purified T cells. MoDCs treated with PBS (MOCK) and GST-Cap fusion protein at 0.1, 1, and 5 μg/ml were used as negative controls. Meanwhile, LPS at 0, 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml was used as a positive control. Cell proliferation was measured using the CCK-8 (absorbance at 450 nm). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05 compared with the mock treatment group.

Stimulation of T cell proliferation by PRRSV-infected MoDCs.

T cells, which are characterized by their high CD3 surface expression, represent a substantial fraction of the total PBMC population (Fig. 3C). To ensure that our experiments accurately measured T cell proliferation, we purified T cells from PBMCs using FACS. The resulting preparation, based on CD3 expression, was 99% CD3+ T cells (Fig. 3D). We tested MoDC stimulatory activity in mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLR) after infection with PRRSV with or without LPS. As shown in Fig. 3E, T cell proliferation was impaired as PRRSV infection dose increased. LPS-treated MoDCs and PRRSV-infected MoDCs that have been treated with anti-CD83 stimulate T cell proliferation to significantly higher levels than those treated with rabbit IgG (20 μg/ml) (P < 0.05). MoDCs treated with LPS (10 μg/ml) alone exhibit an enhanced ability to stimulate T cell proliferation. This suggests that PRRSV specifically suppresses T cell proliferation via sCD83. To further test whether sCD83 treatment of MoDCs suppresses T cell proliferation, MoDCs were treated with GST-sCD83 at 0.1, 1, and 5 μg/ml and cocultured with T cells. GST-Cap (0.1, 1, and 5 μg/ml) was used as a negative control and LPS (1, 5, and 10 μg/ml) as a positive control. Figure 3F shows that GST-sCD83 protein depresses proliferation in a dose-dependent manner. Combining these results with those from the previous section, we conclude that PRRSV infection has a strong inhibitory effect on the MHC-peptide complex in MoDCs and inhibits the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cell proliferation. Both effects are associated with sCD83 shed from MoDCs.

PRRSV Nsp1α stimulates the CD83 promoter.

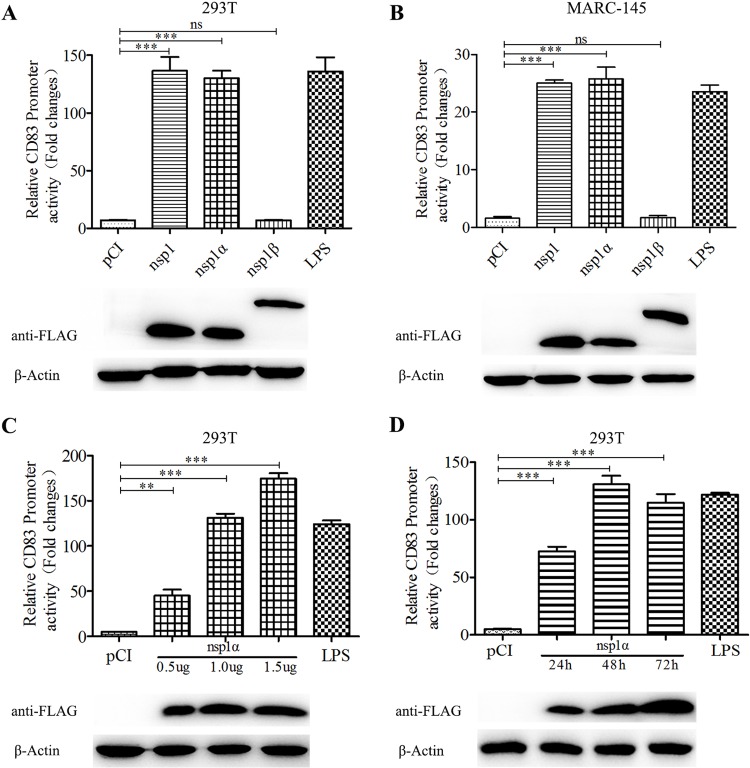

Our previous studies demonstrated that Nsp1 stimulates CD83 promoter activity (53). To examine activation of the CD83 promoter more closely, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and monkey embryonic kidney epithelial 145 (MARC-145) cells were cotransfected with pCD83-luc and pRL-TK, together with a plasmid encoding Nsp1, Nsp1α, or Nsp1β. The results show that Nsp1α is required to regulate the CD83 promoter (Fig. 4A and B). Additional experiments revealed that CD83 promoter activity responds to Nsp1α in a dose-dependent manner (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C). Promoter activity increases from 24 to 48 h postinfection (hpi) and is maintained as long as 72 hpi (Fig. 4D). Because Nsp1 undergoes autocleavage to generate Nsp1α and Nsp1β and the FLAG tag is fused to the N terminus, the anti-FLAG antibody reveals no appreciable distinction in the sizes of Nsp1 and Nsp1α in our Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A and B).

FIG 4.

CD83 promoter activity is increased by PRRSV Nsp1α. (A and B) Effects of Nsp1 and its autocleaved products on the activity of the pCD83 promoter. Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells and MARC-145 cells were cotransfected with plasmids pCI (negative control), pCI-Nsp1, pCI-Nsp1α, or pCI-Nsp1β, along with pCD83-luc and pRL-TK. After incubation for 36 h, CD83 promoter activity was analyzed using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay. Extracts from transfected cells were also subjected to Western blotting to detect Nsp1, Nsp1α, and Nsp1β expression. pCI-transfected cells served as a negative control, and pCI-transfected cells stimulated with LPS 20 h prior to harvest served as a positive control. (C) pCD83 promoter activity is induced by Nsp1α in a dose-dependent manner. (D) pCD83 promoter activity increases with time after transfection. All assays were repeated at least three times, with each experiment performed in triplicate. Bars represent means ± SEMs from three independent experiments. Three asterisks indicate significant difference between groups (P < 0.001).

Mutations in Nsp1α reduce its ability to stimulate the CD83 promoter.

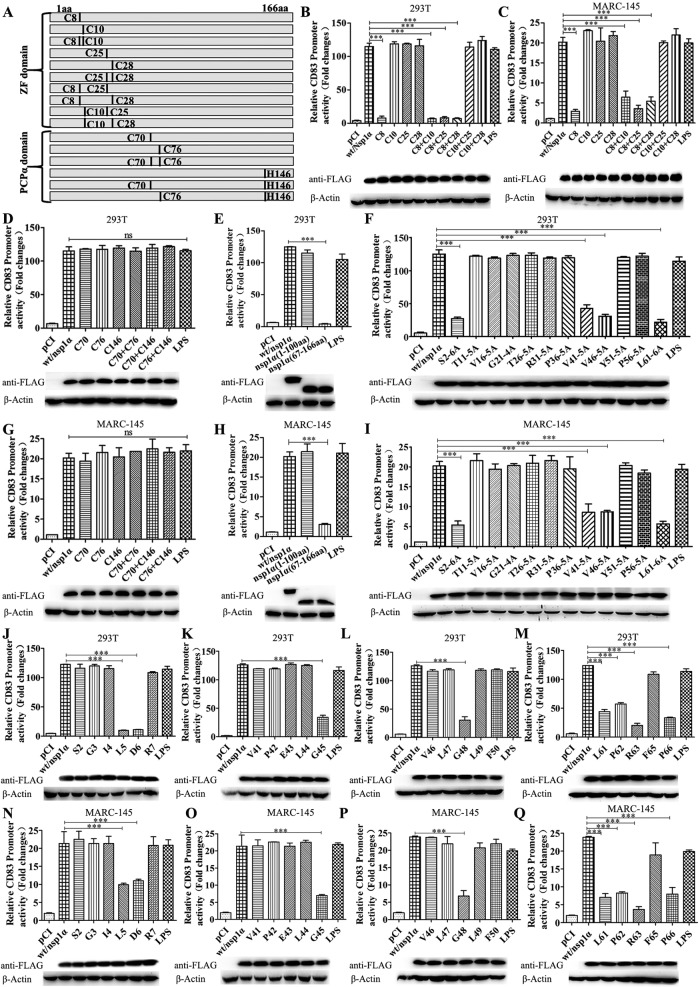

PRRSV Nsp1α contains an amino-terminal ZF domain and a PCP domain. Four cysteine residues at positions 8, 10, 25, and 28 in the ZF domain and three at positions 70, 76, and 146 in the PCP domain are crucial for Nsp1α function. We therefore constructed a series of plasmids in which C8, C10, C25, C28, C8/C10, C8/C25, C8/C28, C10/C25, C10/C28, and C25/C28 were replaced with alanine. The constructs also included a Flag tag at the N terminus (Fig. 5A). Each plasmid was cotransfected with pCD83-luc and pRL-TK into HEK 293T and MARC-145 cells. Using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay, we found that only the mutation at C8 abolished the ability of Nsp1α to induce the CD83 promoter (Fig. 5B to D and G).

FIG 5.

Identification of the Nsp1α domain responsible for CD83 modulation. (A) Mutations affecting one or two cysteine residues were constructed in the Nsp1α ZF and PCP domains. (B to Q) HEK 293T or MARC-145 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cotransfected with 1 μg pCD83 and 1 μg pCI-Nsp1α or mutant plasmid together with 100 ng pRL-TK. Forty-eight h after transfection, cells were lysed and analyzed using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay for CD83 promoter activation. Cells transfected with pCI served as a negative control, and cells transfected with pCI and stimulated with LPS 20 h prior to harvest served as a positive control. Nsp1α levels in cells lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B and C) Mutants affecting the ZF domain; (D and G) mutants affecting the PCP domain; (E and H) Nsp1α truncation mutants; (F and I) constructs containing adjacent alanine substitutions; (J and N) individual alanine substitutions affecting residues 2 to 7; (K and O) individual alanine substitutions affecting residues 41 to 45; (L and P) individual alanine substitutions affecting residues 46 to 50; (M and Q) individual alanine substitutions affecting residues 61 to 66.

These data suggest that the ZF domain, rather than the PCP domain, is responsible for stimulating expression from pCD83-luc. In order to confirm domain functionality, Nsp1α truncation mutants were constructed in plasmid vector pCI, encoding either the first 100 N-terminal amino acids or C-terminal residues 67 to 166 and again including an N-terminal Flag tag. HEK 293T and MARC-145 cells were then transfected with pCD83-luc, pRL-TK, and pCI-Nsp1α or the truncated constructs. The results show that residues 67 to 166 do not confer the ability to stimulate CD83 promoter activity (Fig. 5E and H), while the ZF domain is sufficient to do so. The ZF domain was examined at higher resolution using 12 mutants encoding the substitutions S2-6A, T11-5A, V16-5A, G21-4A, T26-5A, R31-5A, P36-5A, V41-5A, V46-5A, Y51-5A, P56-5A, and L61-6A. Four (S2-6A, V41-5A, V46-5A, and L61-6A) were impaired in their ability to stimulate the CD83 promoter (Fig. 5F and I). Additional point mutations were then introduced in selected regions encoding amino acids 2 to 7, 41 to 45, 46 to 50, and 61 to 66 within the ZF domain. Mutants with modifications at L5 (Leu5), D6 (Asp6), G45 (Gly45), G48 (GLy48), L61 (Leu61), P62 (Pro62), R63 (Arg63), and P66 (Pro66) were unable to induce CD83 promoter activity (Fig. 5J to Q).

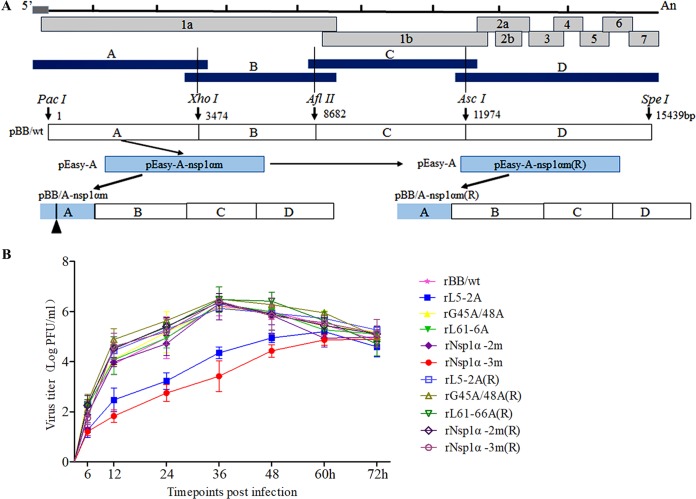

Construction and identification of Nsp1α mutant and repair viruses.

To confirm the identity of the amino acid residues responsible for CD83 promoter activation, viruses containing mutations in nsp1α were constructed using PRRSV infectious cDNA clones (Fig. 6A). Five viruses were successfully rescued. These were rL5-2A (mutant sites at residues L5 and D6), rG45A/G48A (mutations at G45 and G48), rL61-6A (mutations at L61, P62, R63, F65, and P66), rNsp1α-2m (includes the mutations in rG45A/G48A and rL61-6A), and rNsp1α-3m (includes the mutations in rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, and rL61-6A). The repaired viruses rL5-2A(R), rL61-6A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R) were functional, as judged by the presence of cytopathic effect 4 days posttransfection. Multistep growth kinetic analysis showed that rL5-2A and rNsp1α-3m grew more slowly than wild-type rBB/wt early in infection, resulting in approximately 10-fold and 50-fold differences in titer, respectively (Fig. 6B). The other eight virus constructs exhibited growth kinetics similar to those of the parental wild-type rBB/wt virus (Fig. 6B).

FIG 6.

Construction and identification of Nsp1α mutant and repaired viruses. (A) Construction strategy for full-length cDNA clones for the mutant nsp1α and the repaired nsp1α of PRRSV. (B) Multistep growth kinetics of PRRSV in MARC-145 cells after infection by the indicated viruses at an MOI of 0.1. Culture supernatant was collected at the indicated time points for viral titration. Results are expressed as 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50). Titers from three independent experiments are shown as means ± SEM (error bars).

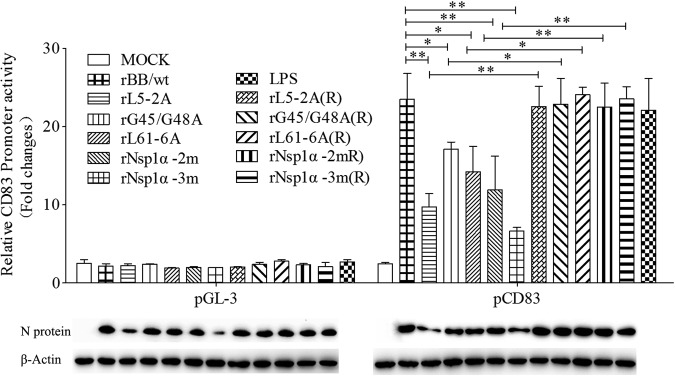

Effect of nsp1α mutant viruses on CD83 promoter activity and CD83 expression in MoDCs.

To verify that the nsp1α mutant viruses are unable to increase CD83 production, Dual-Luciferase assays were performed. The results show that the mutants are decreased in their ability to activate the pCD83 promoter compared with the wild-type virus rBB/wt. The repaired viruses induce pCD83 almost as well as rBB/wt (Fig. 7). The level of virus infection was determined by Western blotting using anti-N protein monoclonal antibody (MAb). Levels of N-protein produced by mutants rL5-2A and rNsp1α-3m are consistent with their attenuated growth kinetics.

FIG 7.

Effect of Nsp1α mutant viruses on CD83 promoter activity. MARC-145 cells were cotransfected with pCD83-luc (1 μg) and pRL-TK (0.1 μg). Twenty-four h later, they were inoculated with PRRSV rBB/wt, rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, rL61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, rNsp1α-3m, rL5-2A(R), rL61-6A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R) at an MOI of 1. Lysates from LPS-treated and mock-infected cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. CD83 promoter activation was analyzed using a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay. The panel below the bar graph shows immunoblots of proteins from infected cells probed with anti-N and anti-β-actin. Data represent the average relative luciferase units from three independent experiments (means ± SEM).

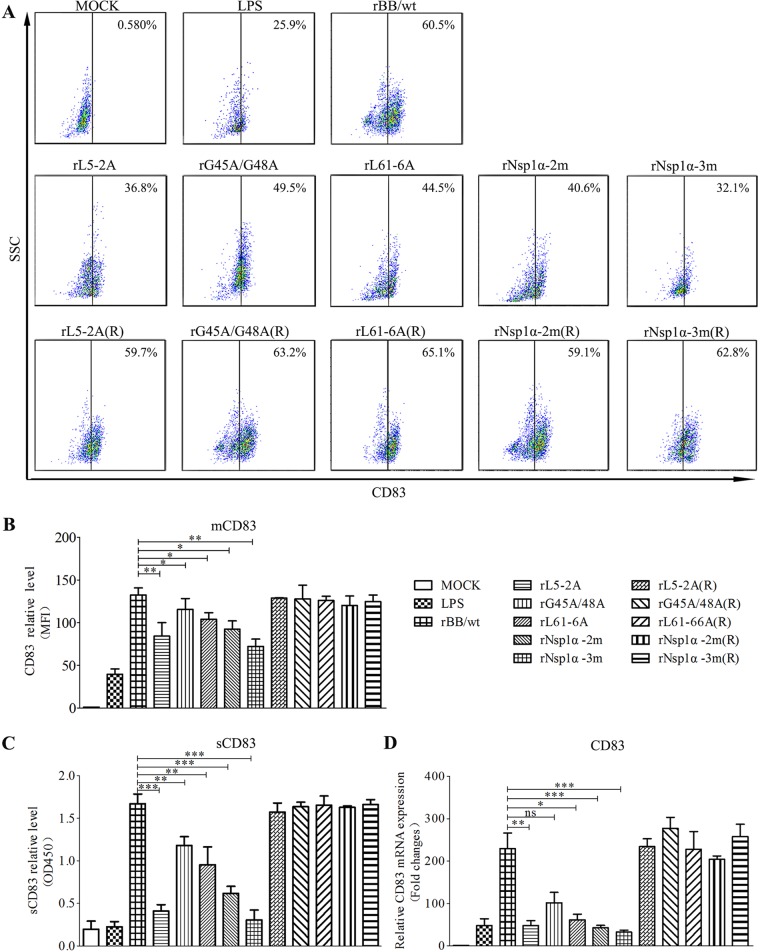

Changes in mCD83 production in infected MoDCs were assessed by FACS. Figure 8A and B show the analysis of cells infected with wild-type rBB/wt, nsp1α mutants, and repaired viruses in the presence of LPS 24 h after infection. sCD83 protein levels and CD83 mRNA levels were assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 8C) and qRT-PCR (Fig. 8D). These data show that MoDCs infected with the Nsp1α mutants produced lower levels of mCD83, sCD83, and CD83 mRNA than the corresponding repaired viruses. Cells infected with rNsp1α-2m express the lowest levels of CD83 of the mutants, whose virus titers are similar to those of wild-type rBB/wt.

FIG 8.

Effect of nsp1α mutations on CD83 expression. (A) MoDCs were mock infected or infected with PRRSV mutants [rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, rL61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, rNsp1α-3m, rL5-2A(R), rL61-6A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R)] at an MOI of 1 in the presence of LPS (10 μg/ml). After 24 h, cells were analyzed for surface CD83 (mCD83) expression by flow cytometry. Cells were stained with an isotype-matched control antibody. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; y axis) values are shown for each virus. (C) Culture supernatants were collected and sCD83 was analyzed by ELISA. (D) CD83 mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR. All assays were repeated at least three times, with each experiment performed in triplicate. Bars represent means ± SEM from three independent experiments. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

Effect of nsp1α mutant viruses on expression of TAP1 and ERp57 and stimulation of T cell proliferation by sCD83 in MoDCs.

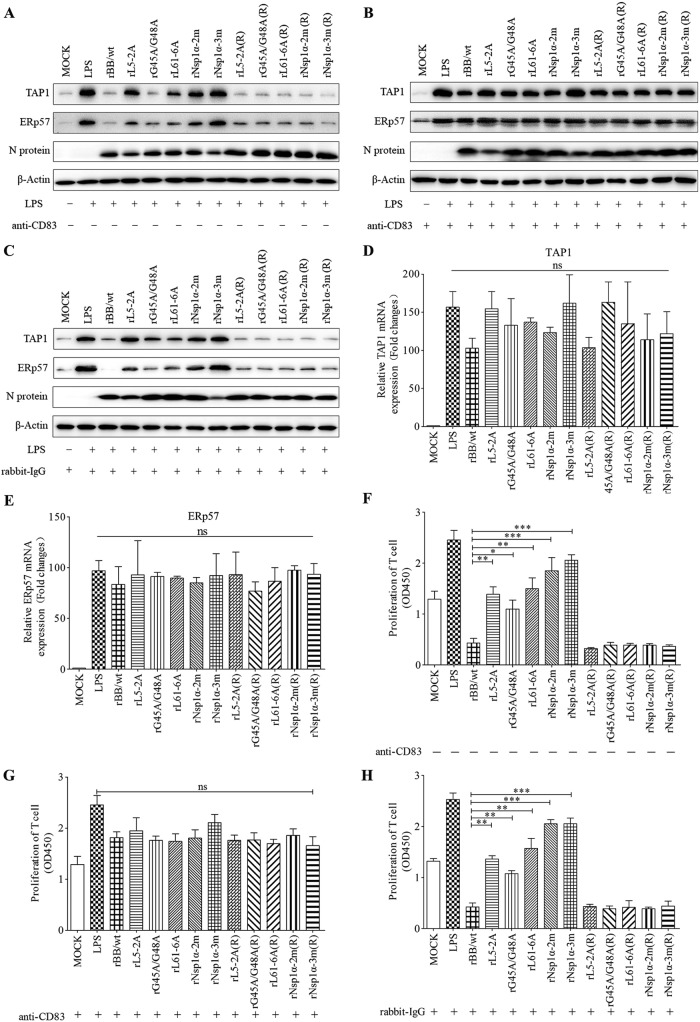

To determine whether mutant viruses affect expression of TAP1 and ERp57, MoDCs were left untreated or were treated with anti-CD83 (20 μg/ml) or rabbit IgG (20 μg/ml) for 1 h and then infected with nsp1α mutant virus at an MOI of 1 in the presence of LPS. Twenty-four h after infection, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 9A and C, TAP1 and ERp57 levels were higher in untreated cells infected by rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, r61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, and rNsp1α-3m than in cells infected by wild-type rBB/wt or repaired virus. In contrast, in anti-CD83-treated MoDCs, TAP1 and ERp57 levels were indistinguishable in cells infected by wild-type rBB/wt, nsp1α mutants, or repaired virus (Fig. 9B). The qRT-PCR results indicate that TAP1 and ERp57 mRNA levels are not affected by infections with wild-type rBB/wt or nsp1α mutant viruses (Fig. 9D and E).

FIG 9.

Nsp1α mutations impair the ability of PRRSV to depress immunoregulatory activity of MoDCs. (A to C) MoDCs were mock infected or infected with recombinant PRRSV [rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, rL61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, rNsp1α-3m, rL5-2A(R), rL61-6A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R)] at an MOI of 1 in the presence of LPS (10 μg/ml) with (A) or without (B) culture medium preprocessed with anti-CD83 or rabbit-IgG (C). After incubation for 24 h, cell lysates were examined by Western blotting with anti-TAP1 or anti-ERp57 antibodies. Replication of PRRSV was analyzed by Western blotting using anti-N protein. Endogenous β-actin expression was used as an internal control. Data are representative of three experiments. (D and E) TAP1 and ERp57 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR. (F to H) MoDCs were treated as described above, and supernatants were added to T cells at 10%, vol/vol. T cell proliferation stimulated by MoDCs increased significantly when the supernatants were generated using PRRSV Nsp1 mutant viruses (F) or treated with anti-CD83 antibody (G) or rabbit-IgG (H). Proliferation was measured as absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are represented as means ± SEM. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05.

In parallel, PRRSV-infected cells from the experiments described above were mixed with T cells at a DC/T cell ratio of 1:10 and cultured for 5 days, and then T cell proliferation was measured. As shown in Fig. 9F and H, T cell proliferation was higher in MoDCs infected by mutant viruses than in cells infected with wild-type rBB/wt or repaired viruses. However, when MoDCs were pretreated with anti-CD83, there were no significant differences in T cell proliferation among any of the viruses tested (Fig. 9G).

DISCUSSION

PRRSV infection causes a delayed and defective adaptive immune response in swine that facilitates viral immune evasion from host defenses (3). DCs play a fundamental role in the initiation of the immune response. One of the most important functions of MoDCs is to load MHC-I molecules with peptides derived from phagocytosed antigens in a process known as cross-presentation (54). The MHC class I complex contains several proteins, of which the most important are TAP1 and ERp57 (30). Some viruses have evolved strategies to escape immune surveillance by targeting TAP1 and ERp57 expression or function (34, 41). TAP1 levels can be decreased by adenovirus E1A and the human papillomavirus, thus inhibiting peptide transport (55). ICP47 from HSV directly downregulates TAP1 expression and inhibits peptide binding in a competitive manner (56). HCMV-, HIV-, and pseudorabies virus (PRV)-infected porcine cells exhibit alterations in peptide transport (55). The US2 and US11 proteins of HCMV localize to the ER and interact with newly synthesized MHC-peptide complexes, targeting them to the ERAD machinery for degradation within minutes of synthesis (35). In this study, we found that PRRSV infection suppresses MoDC activity, impairs the expression of the MHC-peptide complex molecules TAP1 and ERp57, and reduces MoDC-mediated T cell proliferation.

CD83, a type I Ig superfamily glycoprotein, is a well-known surface marker for mature dendritic cells (44). However, CD83 also is found in a soluble form in human sera, likely as a result of shedding from cell membranes (57), and appears to be immunosuppressive. Soluble CD83 also exists in pig sera, and pig sCD83 shares 87% amino acid sequence homology with the human sCD83 protein (53). sCD83 interrupts the differentiation of monocytes into DCs and mediates T cell suppression via prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), which is produced by monocytes (47). HCMV also infects human DCs and suppresses allogeneic T cell proliferation by inducing the release of sCD83 (51). E. coli-expressed sCD83 displays high levels of suppression in mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLRs) in vitro and can reverse established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in vitro and in vivo (58). Although CD83 plays essential roles in both the central and peripheral immune systems, the underlying mechanisms by which CD83 regulates immune responses remain unknown, and how CD83 and sCD83 exert opposite regulatory effects on the immune system is not understood. To explore sCD83 function, we purified a GST-tagged CD83 protein using an E. coli expression system and then added it to MoDC cultures at several concentrations. The results show that GST-sCD83 protein specifically inhibits the expression of TAP1 and ERp57 protein, but it does not significantly influence the mRNA level of TAP1 and ERp57. This indicates that the impact of TAP1 and ERp57 expression by sCD83 mainly occurs at the posttranscriptional translation and posttranslational modification stage rather than transcription. Furthermore, the ability of MoDCs to stimulate allogeneic T cell responses was reduced in a dose-dependent manner by the GST-sCD83 protein. PRRSV itself upregulates CD83 expression and stimulates the release of sCD83 from infected MoDCs. However, coincubation of PRRSV-exposed MoDCs with anti-CD83 antibody efficiently blocks the inhibitory effect of sCD83 on MHC-peptide molecules. This indicates that PRRSV inhibits TAP1 and ERp57 expression and decreases the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cells by increasing the release of sCD83 from infected MoDCs. We note that Western blot results show that ERp57 expresses with different molecular weights, as shown in Fig. 2D and 3A and B. This may be due to the glycosylation of the protein. ERp57 is an ER luminal glycoprotein-specific thiol oxidoreductase, and its function is related to glycosylation (41, 59, 60).

PRRSV proteins are involved in the modulation of the immune response (3, 7). PRRSV Nsp1α plays multiple roles in supporting viral escape from immune surveillance (11–13, 15, 17, 18). Nsp1α suppresses the ability of amino acid F176 in the CTE domain to induce IFN-β (15). Amino acid residues Gly90, Asn91, Arg97, Arg100, and Arg124 in Nsp1α are required to suppress TNF-α production (11). The Nsp1α ZF1 motif is involved in CBP degradation, which is the key mechanism for IFN suppression (18). Nsp1α also has the ability to inhibit NF-κB activation, which is associated with IFN and TNF-α downregulation during PRRSV infection (12). Here, our results show that a mutation affecting Cys8 abolishes the ability of Nsp1α to stimulate the production of CD83, suggesting that the zinc finger domain is required for this process. In contrast, mutations affecting Cys70, Cys76, and His146 in the PCP domain do not affect CD83 production. Additional mutagenesis of Nsp1α revealed that L5 (Leu5), D6 (Asp6), G45 (Gly45), G48 (GLy48), L61 (Leu61), P62 (Pro62), R63 (Arg63), and P66 (Pro66) are important for the induction of CD83 promoter activity. To confirm these results, we constructed recombinant PRRSV with mutations at these positions and examined their ability to induce CD83 expression in infected MARC-145 cells and MoDCs. The mutants L5-2A, G45A, G48A, L61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, and rNsp1α-3m induced significantly different levels of CD83, TAP1, and ERp57 expression and T cell proliferation than the wild-type virus and the repaired viruses. This indicates that the ZF domain of Nsp1α plays a critical role in stimulating the secretion of CD83, which in turn inhibits MoDC function.

In our previous studies, we found that the viral nucleocapsid protein, Nsp1, and Nsp10 enhance CD83 promoter activity. Amino acid residues 43 and 44 in N protein and aa 192 to 195 and 214 to 213 of Nsp10 are crucial for comprehensive expression of CD83 under stimulation by PRRSV (53). Based on those studies, we propose that PRRSV infection induces CD83 expression in porcine MoDCs via the Nsp1 protein. Alteration of the APC functions then results in PRRSV-specific T cell proliferation. In support of these hypotheses, we showed that the accumulation of viral Nsp1α, activation of the CD83 promoter, and residues L5A, D6A, G45A, G48A, L61A, P62A, R63A, F65A, and P66A of Nsp1α are of vital importance in PRRSV-mediated CD83 upregulation. However, the mutant viruses slightly decrease the expression of mCD83, sCD83, and CD83 mRNA in MoDCs and inhibit the function of MoDCs relative to the effects seen in a mock infection. This suggests that other viral genes, such as nsp2 and nsp4, have inhibitory effects on MoDCs and MoDC-mediated T cell proliferation. The data presented here clearly show for the first time that viral protein Nsp1α from PRRSV regulates CD83 expression and modulates expression of TAP1 and ERp57 in MoDCs to influence MoDC-mediated T cell proliferation in vitro. mCD83, sCD83, and CD83 mRNA may have vital roles in the modulation of innate immune responses in PRRSV-infected pigs and may help to clear the virus in vivo.

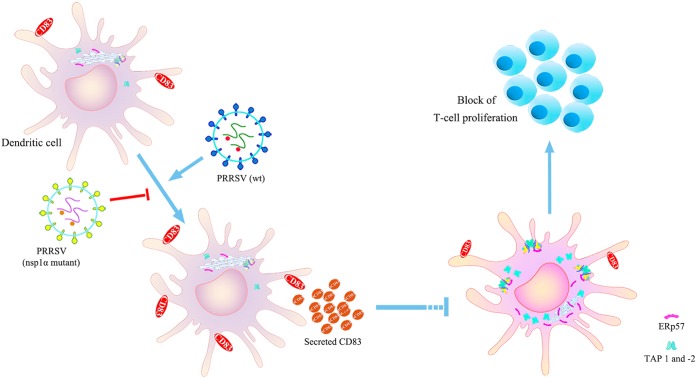

In summary, we have shown that PRRSV infection decreases expression of the MHC-peptide complex components TAP1 and ERp57 in MoDCs and inhibits the ability of MoDCs to stimulate the proliferation of T cells. These effects are largely due to the increase in soluble CD83 that accompanies viral infection. We also demonstrated that PRRSV Nsp1α stimulates CD83 promoter activity, and the mutants L5A, D6A, G45A, G48A, L61A, P62A, R63A, F65A, and P66A in the ZF domain of Nsp1α specifically interfere with this function (Fig. 10). Our results illuminate the mechanism underlying immune escape during viral infection and reveal that soluble CD83 plays a critical role in the adaptive immune response.

FIG 10.

Inhibitory effects of PRRSV infection on MoDC activity are mediated by soluble CD83. Infection of MoDCs by PRRSV increases CD83 production and especially the release of soluble CD83. sCD83 strongly decreases the expression of the MHC-peptide complex proteins TAP1 and ERp57 and then inhibits the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cell proliferation. Viruses containing mutations in L5A, D6A, G45A, G48A, L61A, P62A, R63A, F65A, and P66A do not affect CD83 expression or depress the ability of MoDCs to stimulate T cell proliferation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from PRRSV antibody-negative pigs. This is classified as a negligible risk to the donors. All animals were housed in the animal facility of Nanjing Agricultural University (NAU), Nanjing, Jiangsu, China. All animal experimental protocols conformed to the National Guidelines for Housing and Care of Laboratory Animals (China) and were performed in accordance with NAU institutional regulations after approval by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of NAU (permit no. IACECNAU20160102).

Cells and virus.

HEK 293T cells (a human embryonic kidney cell line) and MARC-145 cells (a monkey embryonic kidney epithelial cell line) were obtained from the ATCC and maintained in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37°C. Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; GIBCO) containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

HP-PRRSV BB0907 was isolated in 2009 in Guangxi Province, China. It was passaged 10 times through MARC-145 cells and maintained as a stock in our laboratory (GenBank accession no. HQ315835). This isolate is referred to as BB. Recombinant viruses rBB/wt, rL5-2A (mutant sites at residues L5 and D6), rG45A/G48A (mutations at G45 and G48), rL61-6A (mutations at L61, P62, R63, F65, and P66), rNsp1α-2m (includes the mutations rG45A/G48A and rL61-6A), rNsp1α-3m (includes the mutations rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, and rL61-6A), and their respective repair viruses, rL5-2A(R), rL61-6A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R), were derived from the infectious construct pCMV-BB0907 and propagated in MARC-145 cells.

Production and characterization of sCD83 protein.

Porcine sCD83 cDNA was amplified from mature dendritic cells by RT-PCR using primer 1 (5′-CGCGGATCCATGGCGCGCGGCCTCCAGTTCCTGC-3′; internal BamHI site underlined) and primer 2 (5′-CCGCTCGAGTCATTTCTTAAAAGTATCTTCTTTG-3′; internal XhoI site underlined). The amplicon was gel purified, verified by sequencing, and then inserted into pGEX-6p-1. The ligation products were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells (Novagen, Schwalbach/Ts, Germany). The positive transformants were selected by DNA sequencing (data not shown). Transformants were cultured at 37°C until reaching the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6 to 0.8 and then induced with 1 mM IPTG at 37°C for 4 h (61). GST-sCD83 fusion proteins were identified by SDS-PAGE and purified using a Pierce GST protein interaction pull-down kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo, USA). The purity of the GST-sCD83 fusion protein was greater than 98%, as estimated using thin-layer gel optical scanning. Protein concentration was determined using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) protein assay kit (Kang Wei, China). The specificity of sCD83 protein was analyzed by sandwich ELISA (62).

GST-Cap fusion protein, containing the Cap protein of porcine circovirus type 2, was expressed and purified using the methods described above. It has no influence on CD83 production in MoDCs and was used as a negative-control protein in experiments with GST-sCD83 fusion protein.

Isolation of porcine PBMC, T cells, and MoDCs.

PBMCs were isolated from PRRSV antibody-negative donors by Ficoll-Paque density centrifugation.

T cells were stained with CD3+ antibodies and purified by FACS (BD FACS Aria Fusion; BD Biosciences), resulting in >98% purity. T cells and PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma) (23).

Monocytes were allowed to attach to wells (2 × 106/well in a 6-well plate). After 4 h,s nonadherent cells were aspirated. Adherent cells were incubated in RPMI 1640 medium with 100 ng/ml granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rpGM-CSF; R&D Systems) and 20 ng/ml interleukin-4 (rpIL-4; R&D Systems). After 7 days cells were harvested as MoDCs and used for subsequent experiments (29, 63).

Preparation of sCD83-treated or PRRSV-infected MoDCs. (i) sCD83 treatment.

MoDCs were suspended in complete medium and transferred to 12-well plates at 1 × 106 cells · ml−1 per well and incubated with sCD83 protein (0.1, 1, 5, and 10 μg/ml) for 24 h. GST-Cap or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as a negative control, while LPS (10 μg/ml) was used as a positive control.

(ii) PRRSV infection. MoDCs were seeded into 12-well plates at 1 × 106 cells · ml−1 per well. MoDCs were incubated with PRRSV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1, 1, or 2, with and without LPS (10 μg/ml). Infection with recombinant PRRSV was at an MOI of 1 with LPS. Mock-infected cells were incubated with complete medium only.

MoDC-mediated allogeneic T cell proliferation.

MoDCs (from sCD83-treated, PRRSV- or rPRRSV-infected, or mock-treated cultures) were mixed with single-donor allogeneic T cells at 1:10 (1 × 103 MoDCs to 1 × 104 T cells). Cells were cultured in RPMI-10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 5 days. T cell number was used as an indicator of the ability of PRRSV-infected MoDCs to inhibit T cell proliferation. Measurements were taken during the last 4 h of the 5-day culture period using a cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) (64). The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Sandwich ELISA for sCD83.

Wells in 96-well plates were precoated with polyclonal rabbit antibody to the CD83 C terminus (2 μg/ml; ab135244; Cambridge, UK) at 4°C overnight. The wells were rinsed three times with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and then blocked with 10% BSA (Life Technologies) in PBS at 4°C overnight. The wells were rinsed, samples were added, and then the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After another rinse, goat anti-CD83(K14) antibody (5 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA, USA) was added and the plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Following rinsing, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-anti-goat antibody (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA, USA) in PBS with 1% BSA was added to the wells, and the plates were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Wells were rinsed a final time and tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was added. The plates were incubated in darkness for 15 min at 25°C. The reaction was stopped with 2 M H2SO4, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate absorbance reader (BioTec, USA) (65, 66).

Western blot analysis.

Levels of TAP1, ERp57, Nsp1α, N protein, and β-actin were measured by Western blotting. Briefly, treated cells were collected and lysed on ice for 30 min in protein isolation buffer, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and then transferred to nitrocellulose. The membrane was blocked with 10% low-fat milk at 37°C for 4 h and then probed with MAb anti-N (1:100; prepared in our laboratory), anti-FLAG (1:800; Cell Signaling Technology), anti-TAP1 (1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-ERp57 (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA, USA), or anti-β-actin (1:1,000; Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at 37°C for 1 h. After washing, the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:1,000; Abcam, MA, USA). Bound proteins were visualized with the Tanon 5200 chemiluminescence imaging system (Tanon, China).

qRT-PCR.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed to measure TAP1, ERp57, and CD83 mRNA levels in MoDCs. Total RNA from mock-, PRRSV-, or rPRRSV-infected MoDCs was extracted using a Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using an RT-PCR kit (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green (Invitrogen) (53). Relative quantification of target gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method, where ΔΔCT = Δ(CTtarget-1 − CTβ-actin-1) − Δ(CTtarget-2 − CTβ-actin-2). Data are presented as fold changes in gene expression, normalized to β-actin and relative to the mock-infected control. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and the data are expressed as means ± standard errors of the means (SEM).

Plasmid construction.

nsp1, nsp1α, and nsp1β were amplified from PRRSV strain BB0907 by RT-PCR. The PCR fragments were ligated into an expression vector (pCI; Invitrogen), which fused them to an N-terminal FLAG tag. Truncated versions of Nsp1α were constructed from the pCI-nsp1α plasmid and designated pCI-Nsp1α (1 to 100 aa) and pCI-Nsp1α (67 to 166 aa). Four- to 6-aa alanine-scanning mutations and point mutations in nsp1α were generated using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. All constructs were confirmed by sequencing (data not shown).

Dual-Luciferase reporter assay.

sCD83 induction was assessed using a reporter gene assay. HEK 293T cells or MARC-145 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cotransfected with the constitutive luciferase control plasmid pRL-TK, the reporter gene plasmid pGL-CD83-luc, and a plasmid expressing Nsp1α or one of its derivatives. After 36 h, activation of the CD83 promoter was assessed using a dual specific luciferase assay kit (Promega, USA). Results are expressed as fold change of relative luminescence compared with that of mock-treated cells. Each experiment was repeated independently three times with three technical replicates. Results were expressed as means ± SEM.

Flow cytometry.

At 24 h postinfection, MoDCs were collected and blocked at 4°C for 30 min with PBS containing 10% BSA and then incubated with goat anti-CD83(K14) (dilution, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA, USA), followed by donkey anti-goat fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; dilution, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotech, CA, USA). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and the data were analyzed using FlowJo version 7.6.1.

Construction of infectious PRRSV cDNA clones.

Fragments containing mutations in nsp1α were obtained by site-directed PCR mutagenesis using pBB/wt as the template. The PCR products were inserted into a pEASY-Blunt Simple vector (designated pEASY-Am). The plasmids were then digested with PacI/XhoI, and fragments containing the mutation were ligated into PacI/XhoI-digested pBB/wt to obtain the full-length mutant cDNA clones pBB/L5-2A, pBB/(G45A/G48A), pBB/L61-6A, pBB/Nsp1α-2m, and pBB/Nsp1α-3m. MARC-145 cells were transfected with each plasmid to generate the mutant viruses rBB/wt, rL5-2A, rG45A/G48A, rL61-6A, rNsp1α-2m, and rNsp1α-3m.

All mutant PRRSV strains were repaired in MARC-145 cells. Briefly, plasmids containing the mutations were modified to restore the nsp1α wild-type genotype. Fragments containing the repaired mutations were ligated into digested pBB/wt. MARC-145 cells were transfected with the resulting full-length cDNA clones to generate repaired PRRSV. The repaired plasmids are designated pBB/L5-2A(R), pBB/(G45A/G48A)(R), pBB/L61-6A(R), pBB/Nsp1α-2m(R), and pBB/Nsp1α-3m(R). The repaired viruses are designated rL5-2A(R), rG45A/G48A(R), rL61-6A(R), rNsp1α-2m(R), and rNsp1α-3m(R).

Transfections were conducted with Lipofectamine 3000 reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. The supernatants were harvested and serially passaged four times in MARC-145 cells, until about 80% of cells exhibited cytopathic effects. Passage 2 to passage 5 virus stocks were prepared in the same manner. All full-length mutant clones were verified by nucleotide sequencing (data not shown). The plasmids were isolated using the QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Qiagen).

One-step viral growth curves.

Subconfluent MARC-145 cells in 24-well plates were inoculated with 106 TCID50 of virus. At 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 72 h postinfection, 100 μl of the infected cell supernatant was removed and 100 μl of fresh medium was added back to each well. All samples were stored at −70°C until virus titration. Virus titers were determined as TCID50.

Statistical analysis.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.0; GraphPad Software). Data are expressed as the means ± SEM, and the significance of the variability among groups was determined with one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Differences for P values of <0.01 and <0.001 are indicated in figures where appropriate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by awards from the National Natural Science Foundation (31672565 and 31230071) for PRRSV immunology, a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture (CARS-36) for swine disease control, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

REFERENCES

- 1.Music N, Gagnon CA. 2010. The role of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus structural and non-structural proteins in virus pathogenesis. Anim Health Res Rev 11:135–163. doi: 10.1017/S1466252310000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rascon-Castelo E, Burgara-Estrella A, Mateu E, Hernandez J. 2015. Immunological features of the non-structural proteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Viruses 7:873–886. doi: 10.3390/v7030873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahe MC, Murtaugh MP. 2017. Mechanisms of adaptive immunity to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Viruses 9:E148. doi: 10.3390/v9060148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Overend CC, Cui J, Grubman MJ, Garmendia AE. 2017. The activation of the IFNβ induction/signaling pathway in porcine alveolar macrophages by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus is variable. Vet Res Commun 41:15–22. doi: 10.1007/s11259-016-9665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Subramaniam S, Piñeyro P, Derscheid RJ, Madson DM, Magstadt DR, Meng X. 2017. Dendritic cell-targeted porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) antigens adjuvanted with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly (I:C)) induced non-protective immune responses against heterologous type 2 PRRSV challenge in pigs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 190:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pileri E, Mateu E. 2016. Review on the transmission porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus between pigs and farms and impact on vaccination. Vet Res 47:108. doi: 10.1186/s13567-016-0391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loving CL, Osorio FA, Murtaugh MP, Zuckermann FA. 2015. Innate and adaptive immunity against porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 167:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Zhang Q, Feng W. 2015. Regulation and evasion of antiviral immune responses by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virus Res 202:101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan B, Liu X, Bai J, Li Y, Zhang Q, Jiang P. 2015. The 15N and 46R residues of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein enhance regulatory T lymphocytes proliferation. PLoS One 10:e138772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wongyanin P, Buranapraditkul S, Yoo D, Thanawongnuwech R, Roth JA, Suradhat S. 2012. Role of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein in induction of interleukin-10 and regulatory T-lymphocytes (Treg). J Gen Virol 93:1236–1246. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.040287-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subramaniam S, Beura LK, Kwon B, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2012. Amino acid residues in the non-structural protein 1 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus involved in down-regulation of TNF-α expression in vitro and attenuation in vivo. Virology 432:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramaniam S, Kwon B, Beura LK, Kuszynski CA, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1 suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter activation by inhibiting NF-κB and Sp1. Virology 406:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Liu S, Sun W, Chen L, Yoo D, Li F, Ren S, Guo L, Cong X, Li J, Zhou S, Wu J, Du Y, Wang J. 2016. Nuclear export signal of PRRSV NSP1α is necessary for type I IFN inhibition. Virology 499:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Shao C, Wang L, Li Q, Song H, Fang W. 2016. The viral non-structural protein 1 alpha (Nsp1alpha) inhibits p53 apoptosis activity by increasing murine double minute 2 (mdm2) expression in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) early-infected cells. Vet Microbiol 184:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi X, Chen J, Xing G, Zhang X, Hu X, Zhi Y, Guo J, Wang L, Qiao S, Lu Q, Zhang G. 2012. Amino acid at position 176 was essential for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) non-structural protein 1α (nsp1α) as an inhibitor to the induction of IFN-β. Cell Immunol 280:125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song C, Krell P, Yoo D. 2010. Nonstructural protein 1α subunit-based inhibition of NF-κB activation and suppression of interferon-β production by porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology 407:268–280. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han M, Du Y, Song C, Yoo D. 2013. Degradation of CREB-binding protein and modulation of type I interferon induction by the zinc finger motif of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nsp1α subunit. Virus Res 172:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi X, Zhang X, Wang F, Wang L, Qiao S, Guo J, Luo C, Wan B, Deng R, Zhang G. 2013. The zinc-finger domain was essential for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein-1α to inhibit the production of interferon-β. J Interferon Cytokine Res 33:328–334. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beura LK, Subramaniam S, Vu HLX, Kwon B, Pattnaik AK, Osorio FA. 2012. Identification of amino acid residues important for anti-IFN activity of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus non-structural protein 1. Virology 433:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi X, Zhang G, Wang L, Li X, Zhi Y, Wang F, Fan J, Deng R. 2011. The nonstructural protein 1 papain-like cysteine protease was necessary for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1 to inhibit interferon-β induction. DNA Cell Biol 30:355–362. doi: 10.1089/dna.2010.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiello S, Rocchetta F, Longaretti L, Faravelli S, Todeschini M, Cassis L, Pezzuto F, Tomasoni S, Azzollini N, Mister M, Mele C, Conti S, Breno M, Remuzzi G, Noris M, Benigni A. 2017. Extracellular vesicles derived from T regulatory cells suppress T cell proliferation and prolong allograft survival. Sci Rep 7:11518. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08617-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin-Gayo E, Buzon MJ, Ouyang Z, Hickman T, Cronin J, Pimenova D, Walker BD, Lichterfeld M, Yu XG. 2015. Potent cell-intrinsic immune responses in dendritic cells facilitate HIV-1-specific T cell immunity in HIV-1 elite controllers. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004930. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wedel J, Hottenrott MC, Stamellou E, Breedijk A, Tsagogiorgas C, Hillebrands J, Yard BA. 2014. N-octanoyl dopamine transiently inhibits T cell proliferation via G1 cell-cycle arrest and inhibition of redox-dependent transcription factors. J Leukoc Biol 96:453. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0813-455R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajah T, Chow SC. 2014. The inhibition of human T cell proliferation by the caspase inhibitor z-VAD-FMK is mediated through oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharm 278:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carbotti G, Nikpoor AR, Vacca P, Gangemi R, Giordano C, Campelli F, Ferrini S, Fabbi M. 2017. IL-27 mediates HLA class I up-regulation, which can be inhibited by the IL-6 pathway, in HLA-deficient small cell lung cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 36:140. doi: 10.1186/s13046-017-0608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peaper DR, Cresswell P. 2008. Regulation of MHC class I assembly and peptide binding. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 24:343–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oda SK, Daman AW, Garcia NM, Wagener F, Schmitt TM, Tan X, Chapuis AG, Greenberg PD. 2017. A CD200R-CD28 fusion protein appropriates an inhibitory signal to enhance T cell function and therapy of murine leukemia. Blood 130:2410–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-777052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillinger B, Ahmadi-Erber S, Soukup K, Halfmann A, Schrom S, Vanhove B, Steinberger P, Geyeregger R, Ladisch S, Dohnal AM. 2017. CD28 blockade ex vivo induces alloantigen-specific immune tolerance but preserves T-cell pathogen reactivity. Front Immunol 8:1152. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Liu P, Xin S, Wang Z, Li J. 2017. Nrf2 suppresses the function of dendritic cells to facilitate the immune escape of glioma cells. Exp Cell Res 360:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawand M, Abramova A, Manceau V, Springer S, van Endert P. 2016. TAP-dependent and -independent peptide import into dendritic cell phagosomes. J Immunol 197:3454–3463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doorduijn EM, Sluijter M, Querido BJ, Oliveira CC, Achour A, Ossendorp F, van der Burg SH, van Hall T. 2016. TAP-independent self-peptides enhance T cell recognition of immune-escaped tumors. J Clin Investig 126:784–794. doi: 10.1172/JCI83671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HK, Lee H, Lew BL, Sim WY, Kim YO, Lee SW, Lee S, Cho IH, Kwon JT, Kim HJ. 2016. Corrigendum: association between TAP1 gene polymorphisms and alopecia areata in a Korean population. Genet Mol Res 14:18820–18827. Genet Mol Res 15:150170751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vakkasoglu AS, Srikant S, Gaudet R. 2017. D-helix influences dimerization of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter associated with antigen processing 1 (TAP1) nucleotide-binding domain. PLoS One 12:e178238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanalioglu D, Ayvaz DC, Ozgur TT, van der Burg M, Sanal O, Tezcan I. 2017. A novel mutation in TAP1 gene leading to MHC class I deficiency: report of two cases and review of the literature. Clin Immunol 178:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chapman DC, Williams DB. 2010. ER quality control in the biogenesis of MHC class I molecules. Semin Cell Dev Biol 21:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hettinghouse A, Liu R, Liu CJ. 2018. Multifunctional molecule ERp57: from cancer to neurodegenerative diseases. Pharmacol Ther 181:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perri E, Parakh S, Atkin J. 2017. Protein disulphide isomerases: emerging roles of PDI and ERp57 in the nervous system and as therapeutic targets for ALS. Expert Opin Ther Targets 21:37–49. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2016.1254197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torres M, Medinas DB, Matamala JM, Woehlbier U, Cornejo VH, Solda T, Andreu C, Rozas P, Matus S, Munoz N, Vergara C, Cartier L, Soto C, Molinari M, Hetz C. 2015. The protein-disulfide isomerase ERp57 regulates the steady-state levels of the prion protein. J Biol Chem 290:23631–23645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.635565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castillo V, Onate M, Woehlbier U, Rozas P, Andreu C, Medinas D, Valdes P, Osorio F, Mercado G, Vidal RL, Kerr B, Court FA, Hetz C. 2015. Functional role of the disulfide isomerase ERp57 in axonal regeneration. PLoS One 10:e136620. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turano C, Gaucci E, Grillo C, Chichiarelli S. 2011. ERp57/GRP58: a protein with multiple functions. Cell Mol Biol Lett 16:539–563. doi: 10.2478/s11658-011-0022-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coe H, Michalak M. 2010. ERp57, a multifunctional endoplasmic reticulum resident oxidoreductase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:796–799. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, Wei MQ, Liu X. 2013. Targeting CD83 for the treatment of graft-versus-host disease. Exp Ther Med 5:1545–1550. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bates JM, Flanagan K, Mo L, Ota N, Ding J, Ho S, Liu S, Roose-Girma M, Warming S, Diehl L. 2015. Dendritic cell CD83 homotypic interactions regulate inflammation and promote mucosal homeostasis. Mucosal Immunol 8:414–428. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prechtel AT, Steinkasserer A. 2007. CD83: an update on functions and prospects of the maturation marker of dendritic cells. Arch Dermatol Res 299:59–69. doi: 10.1007/s00403-007-0743-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stein MF, Lang S, Winkler TH, Deinzer A, Erber S, Nettelbeck DM, Naschberger E, Jochmann R, Sturzl M, Slany RK, Werner T, Steinkasserer A, Knippertz I. 2013. Multiple interferon regulatory factor and NF-κB sites cooperate in mediating cell-type- and maturation-specific activation of the human CD83 promoter in dendritic cells. Mol Cell Biol 33:1331–1344. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01051-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oudijk EJ, Lo TLA, Langereis JD, Ulfman LH, Koenderman L. 2008. Functional antagonism by GM-CSF on TNF-alpha-induced CD83 expression in human neutrophils. Mol Immunol 46:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L, Zhu Y, Zhang G, Gao C, Zhong W, Zhang X. 2011. CD83-stimulated monocytes suppress T-cell immune responses through production of prostaglandin E2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:18778–18783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018994108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horvatinovich JM, Grogan EW, Norris M, Steinkasserer A, Lemos H, Mellor AL, Tcherepanova IY, Nicolette CA, DeBenedette MA. 2017. Soluble CD83 inhibits T cell activation by binding to the TLR4/MD-2 complex on CD14+ monocytes. J Immunol 198:2286–2301. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seldon TA, Pryor R, Palkova A, Jones ML, Verma ND, Findova M, Braet K, Sheng Y, Fan Y, Zhou EY, Marks JD, Munro T, Mahler SM, Barnard RT, Fromm PD, Silveira PA, Elgundi Z, Ju X, Clark GJ, Bradstock KF, Munster DJ, Hart DN. 2016. Immunosuppressive human anti-CD83 monoclonal antibody depletion of activated dendritic cells in transplantation. Leukemia 30:692–700. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pieper D, Schirmer S, Prechtel AT, Kehlenbach RH, Hauber J, Chemnitz J. 2011. Functional characterization of the HuR:CD83 mRNA interaction. PLoS One 6:e23290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Senechal B. 2004. Infection of mature monocyte-derived dendritic cells with human cytomegalovirus inhibits stimulation of T-cell proliferation via the release of soluble CD83. Blood 103:4207–4215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka Y, Mizuguchi M, Takahashi Y, Fujii H, Tanaka R, Fukushima T, Tomoyose T, Ansari AA, Nakamura M. 2015. Human T-cell leukemia virus type-I Tax induces the expression of CD83 on T cells. Retrovirology 12:56. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X, Zhang Q, Bai J, Zhao Y, Wang X, Wang H, Jiang P. 2017. The nucleocapsid protein and nonstructural protein 10 of highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus enhance CD83 production via NF-kappaB and Sp1 signaling pathways. J Virol 91:e00986-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00986-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hüsecken Y, Muche S, Kustermann M, Klingspor M, Palmer A, Braumüller S, Huber-Lang M, Debatin K, Strauss G. 2017. MDSCs are induced after experimental blunt chest trauma and subsequently alter antigen-specific T cell responses. Sci Rep 7:12808. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abele R, Tampe R. 2011. The TAP translocation machinery in adaptive immunity and viral escape mechanisms. Essays Biochem 50:249–264. doi: 10.1042/bse0500249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abele R. 2004. The ABCs of immunology: structure and function of TAP, the transporter associated with antigen processing. Physiology 19:216–224. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lechmann M, Berchtold S, Steinkasserer A, Hauber J. 2002. CD83 on dendritic cells: more than just a marker for maturation. Trends Immunol 23:273–275. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo Y, Li R, Song X, Zhong Y, Wang C, Jia H, Wu L, Wang D, Fang F, Ma J, Kang W, Sun J, Tian Z, Xiao W. 2014. The expression and characterization of functionally active soluble CD83 by Pichia pastoris using high-density fermentation. PLoS One 9:e89264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khanal RC, Nemere I. 2007. The ERp57/GRp58/1,25D3-MARRS receptor: multiple functional roles in diverse cell systems. Curr Med Chem 14:1087–1093. doi: 10.2174/092986707780362871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garbi N, Hammerling G, Tanaka S. 2007. Interaction of ERp57 and tapasin in the generation of MHC class I-peptide complexes. Curr Opin Immunol 19:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maseko SB, Natarajan S, Sharma V, Bhattacharyya N, Govender T, Sayed Y, Maguire GEM, Lin J, Kruger HG. 2016. Purification and characterization of naturally occurring HIV-1 (South African subtype C) protease mutants from inclusion bodies. Protein Expr Purif 122:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huynh T, Ren X. 2017. Producing GST-Cbx7 fusion proteins from Escherichia coli. Bio Protocol 7:e2333. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu J, Qi Y, Xu W, Liu Y, Qiu L, Wang K, Hu H, He Z, Zhang J. 2016. Matrine derivate MASM suppresses LPS-induced phenotypic and functional maturation of murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells. Int Immunopharmacol 36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee H, Lee HW, La Lee Y, Jeon YH, Jeong SY, Lee SW, Lee J, Ahn BC. 2017. Optimization of dendritic cell-mediated cytotoxic T-cell activation by tracking of dendritic cell migration using reporter gene imaging. Mol Imaging Biol 20:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s11307-017-1127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heilingloh CS, Kummer M, Mühl-Zürbes P, Drassner C, Daniel C, Klewer M, Steinkasserer A. 2015. L particles transmit viral proteins from herpes simplex virus 1-infected mature dendritic cells to uninfected bystander cells, inducing CD83 downmodulation. J Virol 89:11046–11055. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01517-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heilingloh CS, Muhl-Zurbes P, Steinkasserer A, Kummer M. 2014. Herpes simplex virus type 1 ICP0 induces CD83 degradation in mature dendritic cells independent of its E3 ubiquitin ligase function. J Gen Virol 95:1366–1375. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.062810-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]