To our knowledge, the effect of BoHV-1 infection on the DNA damage response has not been characterized. Since BoHV-1ΔUL47 was previously shown to be avirulent in vivo, VP8 is critical for the progression of viral infection. We demonstrated that VP8 interacts with DNA damage response proteins and disrupts the ATM-NBS1-SMC1 pathway by inhibiting phosphorylation of DNA repair proteins NBS1 and SMC1. Furthermore, interference of VP8 with DNA repair was correlated with decreased cell viability and increased DNA damage-induced apoptosis. These data show that BoHV-1 VP8 developed a novel strategy to interrupt the ATM signaling pathway and to promote apoptosis. These results further enhance our understanding of the functions of VP8 during BoHV-1 infection and provide an additional explanation for the reduced virulence of BoHV-1ΔUL47.

KEYWORDS: BoHV-1, VP8, DNA damage, DNA repair, apoptosis, UL47, herpesvirus

ABSTRACT

VP8, the UL47 gene product in bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1), is a major tegument protein that is essential for virus replication in vivo. The major DNA damage response protein, ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM), phosphorylates Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS1) and structural maintenance of chromosome-1 (SMC1) proteins during the DNA damage response. VP8 was found to interact with ATM and NBS1 during transfection and BoHV-1 infection. However, VP8 did not interfere with phosphorylation of ATM in transfected or BoHV-1-infected cells. In contrast, VP8 inhibited phosphorylation of both NBS1 and SMC1 in transfected cells, as well as in BoHV-1-infected cells, but not in cells infected with a VP8 deletion mutant (BoHV-1ΔUL47). Inhibition of NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation was observed at 4 h postinfection by nuclear VP8. Furthermore, UV light-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) repair was reduced in the presence of VP8, and VP8 in fact enhanced etoposide or UV-induced apoptosis. This suggests that VP8 blocks the ATM/NBS1/SMC1 pathway and inhibits DNA repair. VP8 induced apoptosis in VP8-transfected cells through caspase-3 activation. The fact that BoHV-1 is known to induce apoptosis through caspase-3 activation is in agreement with this observation. The role of VP8 was confirmed by the observation that BoHV-1 induced significantly more apoptosis than BoHV-1ΔUL47. These data reveal a potential role of VP8 in the modulation of the DNA damage response pathway and induction of apoptosis during BoHV-1 infection.

IMPORTANCE To our knowledge, the effect of BoHV-1 infection on the DNA damage response has not been characterized. Since BoHV-1ΔUL47 was previously shown to be avirulent in vivo, VP8 is critical for the progression of viral infection. We demonstrated that VP8 interacts with DNA damage response proteins and disrupts the ATM-NBS1-SMC1 pathway by inhibiting phosphorylation of DNA repair proteins NBS1 and SMC1. Furthermore, interference of VP8 with DNA repair was correlated with decreased cell viability and increased DNA damage-induced apoptosis. These data show that BoHV-1 VP8 developed a novel strategy to interrupt the ATM signaling pathway and to promote apoptosis. These results further enhance our understanding of the functions of VP8 during BoHV-1 infection and provide an additional explanation for the reduced virulence of BoHV-1ΔUL47.

INTRODUCTION

Upon DNA damage, a variety of cellular responses are induced in eukaryotic cells. Damaged DNA poses a continuous threat to genomic stability, which results in the activation of a network of sensors, transducers, and activator proteins. These proteins conduct different physiological responses, including the arrest of cell cycle progression and activation of DNA repair or, if the damage is too severe, induction of apoptosis or cell death (1, 2). Immediately after exposure to genotoxic stress, the cellular regulatory mechanism is triggered. At the recognition of damaged DNA, highly conserved cellular checkpoint proteins are rapidly induced to prevent cellular replication and damaged DNA propagation before the repair is completed. The major DNA damage response (DDR) signaling network includes ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) protein and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related (ATR) protein. ATM and ATR respond to a variety of abnormal DNA structures, leading to the initiation of a signaling cascade (3). In undamaged cells, ATM exists as a catalytically inactive dimer. After recognition of damaged DNA, ATM undergoes auto- or transphosphorylation at Serine-1981, which leads to catalytically active ATM monomers (4). Consequently, ATM activates downstream proteins, including the Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS1) and structural maintenance of chromosome-1 (SMC1) proteins, to signal checkpoint control (3). ATM activation by double-strand breaks (DSBs) facilitates the recruitment of DNA repair protein NBS1 (5), which leads to checkpoint activation through phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1. SMC1 functions as a downstream effector of the ATM/NBS1 pathway to activate the S-phase checkpoint, which is deficient in ataxia telangiectasia (A-T) and NBS patients (6).

Immediately after infection, cellular antiviral responses are aimed at preventing viral replication and spread. Host cells are exposed to large amounts of exogenous materials or abnormal DNA structures, such as DNA ends, or unusual structures during viral replication. Thus, viral replication is recognized as DNA damage stress by the infected cells and triggers DNA damage signal transduction as a part of host immune surveillance (7).

Herpesviruses are enveloped double-stranded DNA viruses containing ∼150-kbp genomes (8, 9). Upon infection, the viral genome is replicated, producing highly branched replication intermediates. DSBs are generated during herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection (10). Consequently, HSV-1 induces cellular DNA damage responses through activation of ATM and its downstream effector molecules (11). Similarly, other herpesviruses, such as Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), induce ATM activation in primary endothelial cells (12). Murine gamma herpesvirus 68 (γHV68) also induces ATM activation (13). Although gamma herpesvirus M2 protein activates ATM, downstream signaling of the ATM pathway was inhibited by M2 protein (14). Thus, herpesviruses modulate the DNA damage response to favor viral replication in different ways.

Bovine herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1) is an important pathogen in cattle, responsible for a variety of clinical symptoms, in particular respiratory and genital infections. VP8, the UL47 gene product, is the most abundant tegument protein in BoHV-1. BoHV-1 VP8 contains a nuclear localization signal and a nuclear export signal and thereby shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm (15). A UL47-deleted virus (BoHV-1ΔUL47) replicates less efficiently in cell culture and is avirulent in cattle, supporting the importance of VP8 in the establishment of BoHV-1 infection (16). Although the precise role of VP8 in viral infection remains mostly unknown, some functions of VP8 are being elucidated. VP8 interacts with a cellular DNA damage response protein, DDB1 (17). The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1) is also an interacting partner of VP8. However, while the interaction of the paramyxovirus family V protein with DDB1 and STAT1 targets STAT1 for degradation (18), VP8 does not degrade STAT1 or interfere with STAT1 phosphorylation but prevents translocation of STAT1 to the nucleus, thus inhibiting interferon beta (IFN-β) signaling (18). Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) also contributes to DDR activation by interacting with DDB1 (19), and the gamma herpesvirus M2 protein regulates the DDR pathway through interaction with DDB1 and ATM (14).

Since VP8 interacts with DDB1 (17), it was of interest to investigate whether VP8 interacts with other DNA damage response proteins and plays a role in the modulation of the DDR during BoHV-1 infection. The data shown here reveal that VP8 interacts with ATM and NBS1 and prevents phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1. Thus, VP8 disrupts the ATM/NBS1/SMC1 pathway and inhibits DNA repair. Furthermore, VP8 increased DNA damage-induced apoptosis.

RESULTS

VP8 is an interacting partner of ATM and NBS1.

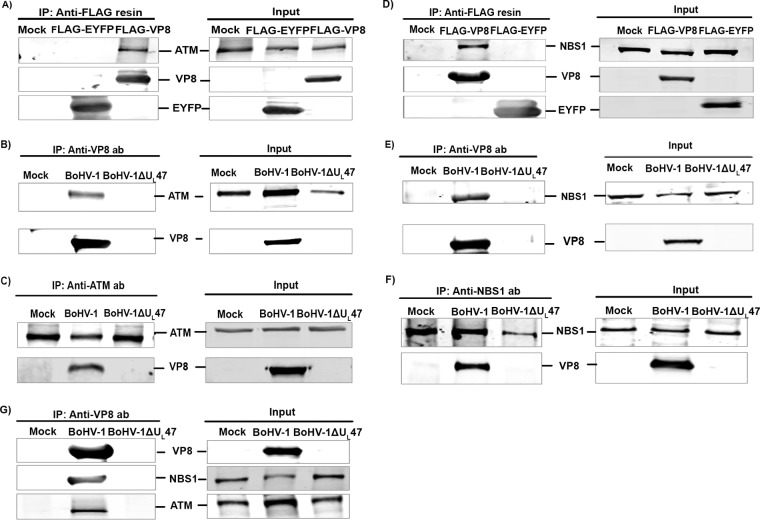

To identify a potential interaction between VP8 and ATM, human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) or pFLAG-VP8. At 24 h posttransfection, cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG beads and immune complexes were detected by anti-FLAG and anti-ATM antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1A, anti-FLAG beads precipitated EYFP and VP8 from pFLAG-EYFP- and pFLAG-VP8-transfected cells, respectively. ATM was precipitated from VP8-transfected cells but not from mock- or EYFP-transfected cells, suggesting that VP8 interacts with ATM. To investigate the interaction of VP8 with ATM during infection, Madin-Darby bovine kidney (MDBK) cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47. Incubation with VP8-specific antibody followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads resulted in precipitation of VP8 and ATM from BoHV-1-infected cells but not from BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells (Fig. 1B). Conversely, VP8 was precipitated with ATM-specific antibody from BoHV-1-infected cells but not from mock- and BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells (Fig. 1C), indicating interaction of VP8 with ATM during BoHV-1 infection.

FIG 1.

VP8 is an interacting partner of ATM and NBS1. (A) HEK 293T cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-EYFP or pFLAG-VP8. Cell lysates were collected at 24 h posttransfection and incubated with anti-FLAG resin. VP8 and ATM were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-FLAG and rabbit anti-ATM antibodies, respectively. (B) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47 at an MOI of 2 and lysed after 24 h. Following incubation with anti-VP8 antibody and protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads, VP8 and ATM were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit anti-ATM antibodies, respectively. (C) BoHV-1 cells were infected as described for Fig. 1B. Infected cells were lysed at 24 h postinfection and incubated with rabbit anti-ATM antibody, followed by incubation with protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads. VP8 and ATM were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit anti-ATM antibodies, respectively. (D) HEK 293T cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-EYFP or pFLAG-VP8. Cell lysates were collected at 24 h posttransfection and incubated with anti-FLAG resin. VP8 and NSB1 were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-FLAG and rabbit anti-NSB1 antibodies, respectively. (E) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47 at an MOI of 2 and lysed after 24 h. Following incubation with anti-VP8 antibody and protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads, VP8 and NSB1 were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit anti-NSB1 antibodies, respectively. (F) BoHV-1 cells were infected as described for Fig. 1E. Infected cells were lysed at 24 h postinfection and incubated with rabbit anti-NSB1 antibody, followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads. VP8 and NSB1 were detected by Western blotting with murine monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit anti-NSB1 antibodies, respectively. (G) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47 at an MOI of 2. At 24 h postinfection cell lysates were collected and incubated with anti-VP8 antibody, followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads. VP8, ATM, and NBS1 were detected by Western blotting with anti-VP8, anti-ATM, and anti-NBS1 antibodies. IRDye 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG were used for detection. Input lysates are presented on the right.

Since ATM forms a complex with NBS1 (5), we investigated whether VP8 also interacts with NBS1. HEK 293T cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-EYFP or pFLAG-VP8. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-FLAG resin followed by detection of immune complexes by anti-FLAG and anti-NBS1 antibodies. As demonstrated in Fig. 1D, anti-FLAG beads precipitated EYFP and VP8 from pFLAG-EYFP- and pFLAG-VP8-transfected cells, respectively. NBS1 was precipitated by anti-FLAG beads from VP8-transfected cells but not from mock- and pFLAG-EYFP-transfected cells, suggesting that VP8 interacts with NBS1. To demonstrate the interaction of VP8 with NBS1 during infection, MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47. Cell lysates from infected cells were incubated with an anti-VP8 antibody followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads. VP8-specific antibody precipitated VP8, as well as NBS1, from BoHV-1-infected cells but not from mock- or BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, incubation of BoHV-1-infected cell lysates with anti-NBS1 antibody followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads precipitated VP8 from BoHV-1-infected cells (Fig. 1F), confirming that NBS1 interacts with VP8 during BoHV-1 infection. To investigate an interaction of VP8 with ATM and NBS1 as a complex, mock-, BoHV-1-, and BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cell lysates were incubated with an anti-VP8 antibody followed by protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads. As shown in Fig. 1G, anti-VP8 antibody pulled down NBS1 as well as ATM from BoHV-1-infected cells but not from mock- and BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells. This experiment demonstrates that VP8 forms a complex with both NBS1 and ATM.

VP8 interferes with the ATM/NBS1/SMC1 pathway by inhibiting phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1.

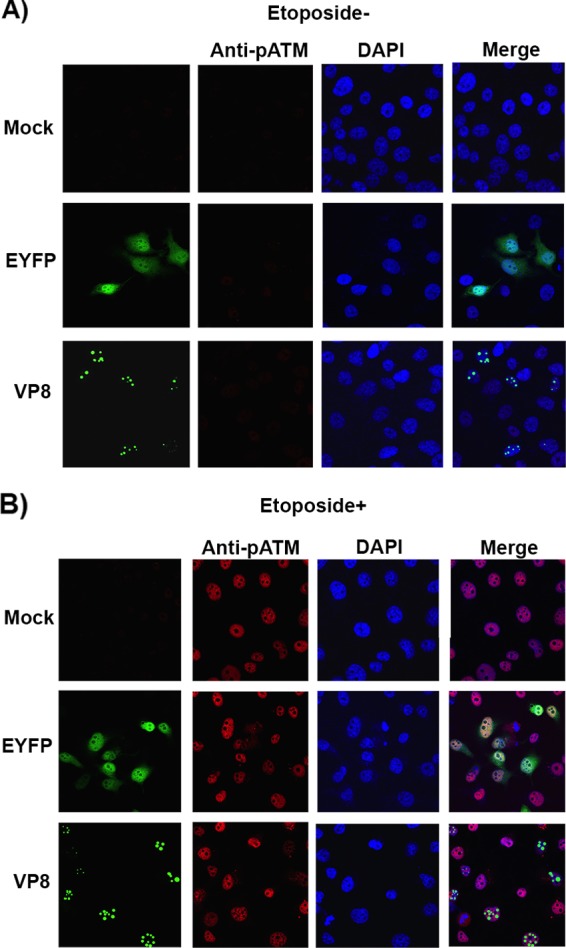

ATM, the checkpoint kinase, acts as a central signal transducer in response to ionizing radiation (IR) (20). Viral proteins, such as hepatitis C virus NS3 protein, interact with ATM and contribute to increased sensitivity of cells to DNA damage (21). Since VP8 interacted with ATM, we investigated whether VP8 influences ATM activation by interfering with its phosphorylation. Human malignant epithelial cells derived from Henrietta Lacks (HeLa) cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min and then were incubated with anti-phospho-ATM (pATM) antibody. Etoposide is a topoisomerase II inhibitor enzyme that generates DNA double-strand breaks by inhibiting religation of DNA strands (22) and activates ATM. As shown in Fig. 2A, in the absence of etoposide, pATM was not detected in mock-, pEYFP- and pVP8-EYFP-transfected cells. As expected, the addition of etoposide enhanced the level of pATM in mock- and pEYFP-transfected cells. Similarly, pATM was observed in the VP8-expressing cells in the presence of etoposide (Fig. 2B). These results suggest that VP8 expression does not interfere with ATM phosphorylation.

FIG 2.

BoHV-1 VP8 does not interfere with ATM phosphorylation. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were left untreated (A) or were treated with etoposide (B). After 30 min of incubation, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and incubated with rabbit anti-pATM antibody, followed by incubation with Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI mounting medium. The cells were examined with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

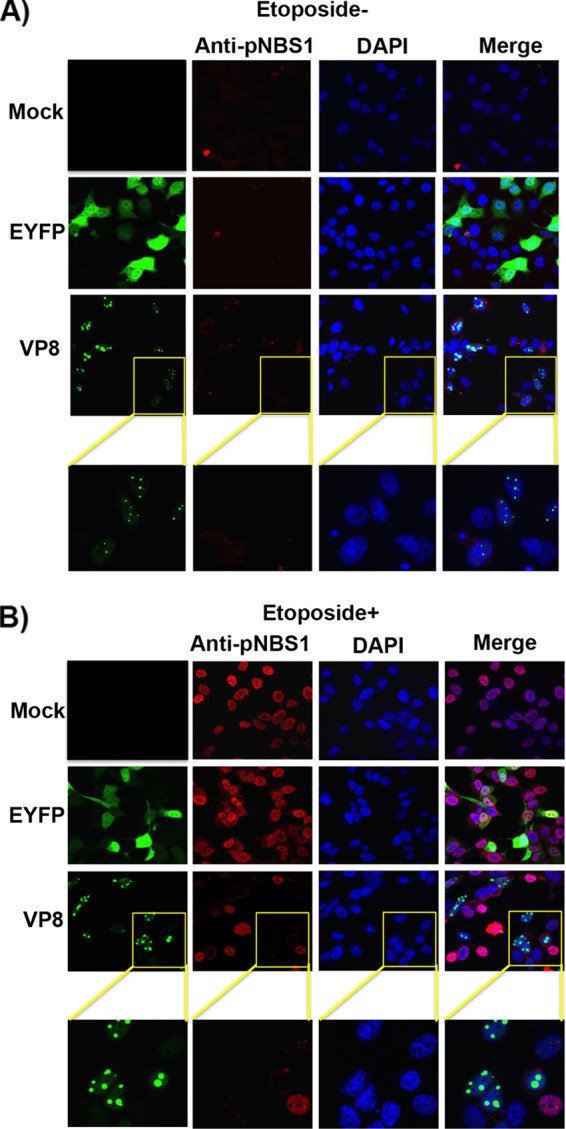

NBS1 is a key player of the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex and identified as a DNA repair protein after initial DNA damage (23). Disruption of the NBS1 function is lethal in mice (24). NBS1 plays a role in the DDR pathway by acting as a downstream target of ATM (5). Since VP8 interacted with ATM and NBS1 without influencing ATM phosphorylation, it was of interest to investigate whether VP8 interferes with phosphorylation of NBS1 as a downstream target. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP and were left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min at 24 h posttransfection. Without etoposide treatment, phosphoNBS1 (pNBS1) was not detected in mock-, EYFP-, and VP8-transfected cells (Fig. 3A). Although in etoposide-treated and mock- and EYFP-transfected cells enhanced pNBS1 was detected, in VP8-expressing etoposide-treated cells no pNBS1 was observed (Fig. 3B), indicating that VP8 prevents phosphorylation of NBS1.

FIG 3.

VP8 inhibits NBS1 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were left untreated (A) or were treated with etoposide for 30 min (B). After fixation, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-pNBS1 antibody followed by Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI. The cells were analyzed with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. The yellow boxes in panels A and B are enlarged in the bottom row.

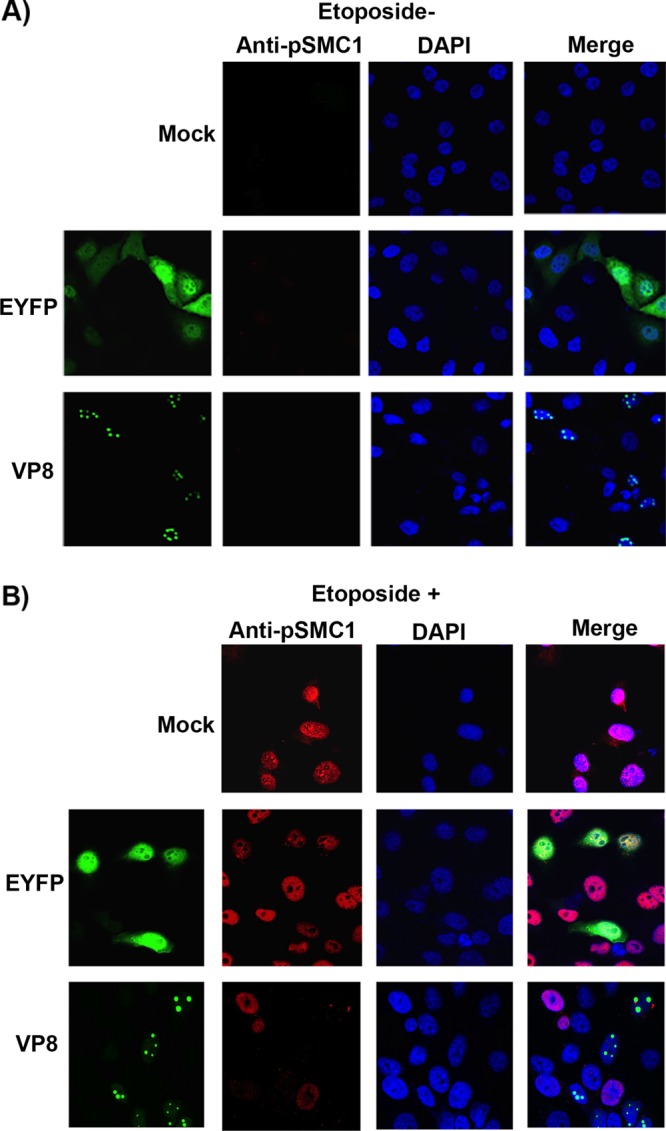

SMC1 acts downstream of the ATM/NBS1 pathway to activate S-phase checkpoint control and initiate DNA repair (6). Since phosphorylation of NBS1 is required for phosphorylation of SMC1 and subsequently for S-phase checkpoint activation (6), we investigated whether VP8 influences phosphorylation of SMC1. Cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP and treated with etoposide as described above. In the absence of etoposide, no phosphoSMC1 (pSMC1) was detected in mock-, EYFP-, and VP8-transfected cells (Fig. 4A). However, after addition of etoposide, SMC1 was phosphorylated in mock- and EYFP-transfected cells as expected but not in VP8-expressing cells (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that VP8 inhibits SMC1 phosphorylation.

FIG 4.

VP8 impedes SMC1 phosphorylation. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were left untreated (A) or were treated with etoposide for 30 min (B). After fixation, cells were incubated with rabbit anti-pNBS1 antibody followed by Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI. The cells were analyzed with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope.

To further confirm the effects of VP8 on phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1, HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were stimulated with etoposide as described above. EYFP-positive cells were sorted using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS). Equal amounts of cell lysate were examined by Western blotting for the presence of pNBS1 and pSMC1 (Fig. 5). While NBS1 and SMC1 were identified, pNBS1 and pSMC1 were not detected in the presence of VP8 after addition of etoposide, confirming the results shown by confocal microscopy. These experiments demonstrate that although VP8 did not interfere with ATM phosphorylation, it inhibited phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1.

FIG 5.

Detection of phosphorylated NBS1 and SMC1 in VP8-transfected cells. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were either left untreated or treated with etoposide for 30 min. EYFP-positive cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting, and cell lysates were made in buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Fifty-microgram aliquots of total protein of each sample were loaded. NBS1, pNBS1, SMC1, pSMC1, EYFP, VP8, and actin were detected by Western blotting with rabbit anti-NBS1, anti-pNBS1, anti-SMC1, and anti-pSMC1 antibodies and murine monoclonal anti-EYFP, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively. IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and IRDye 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG were used for detection.

VP8 does not affect ATM phosphorylation but inhibits NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation during BoHV-1 infection.

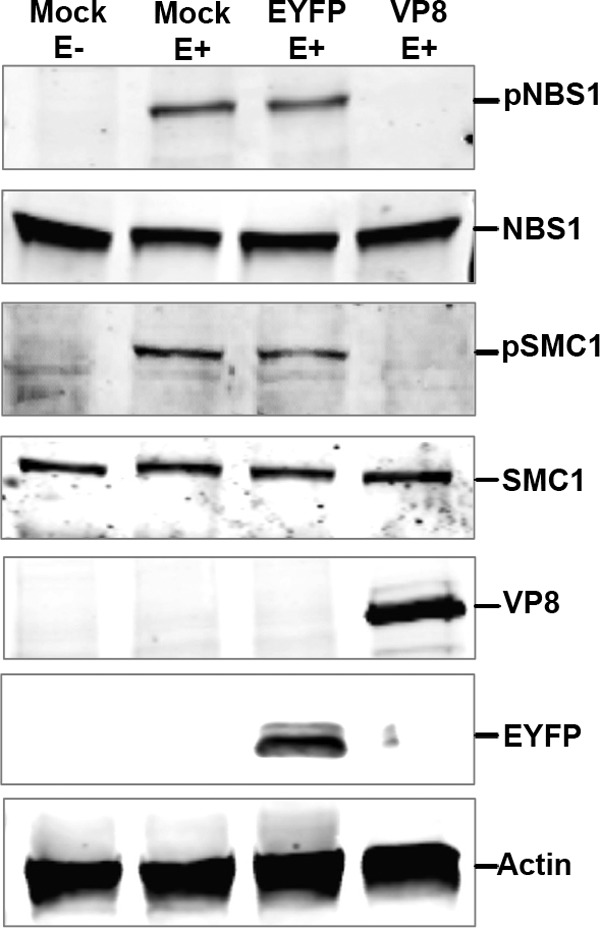

Since VP8 did not interfere with ATM activation but blocked phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1 in transfected cells, we examined the effect of BoHV-1 infection on ATM, NBS1, and SMC1 phosphorylation. MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, or BoHV-1UL47R. At 14 h postinfection, cells were incubated with anti-pATM antibody. BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, and BoHV-1UL47R induced similar levels of ATM phosphorylation (Fig. 6A and B). Since VP8 did not interfere with ATM phosphorylation, etoposide-treated BoHV-1-, BoHV-1ΔUL47-, and BoHV-1UL47R-infected cells were not examined.

FIG 6.

VP8 does not interfere with ATM phosphorylation during BoHV-1 infection. (A) MDBK cells were mock infected, infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4, infected with BoHV-1ΔUL47-EYFP at an MOI of 5, or infected with BoHV-1UL47R at an MOI of 4. At 14 h postinfection, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and incubated with murine monoclonal anti-VP8- or anti-EYFP antibodies and rabbit pATM-specific antibodies. Cells were incubated with Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG. ProLong gold DAPI was used to identify the nuclei. (B) MDBK cells were mock infected, infected with BoHV-1, infected with BoHV-1ΔUL47, or infected with BoHV-1UL47R as described for panel A. At 14 h postinfection, mock-infected cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. Cell lysates were collected, and 50-μg aliquots of total protein of each sample were analyzed by Western blotting. ATM, pATM, VP8, and actin were detected with anti-ATM, anti-pATM, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively.

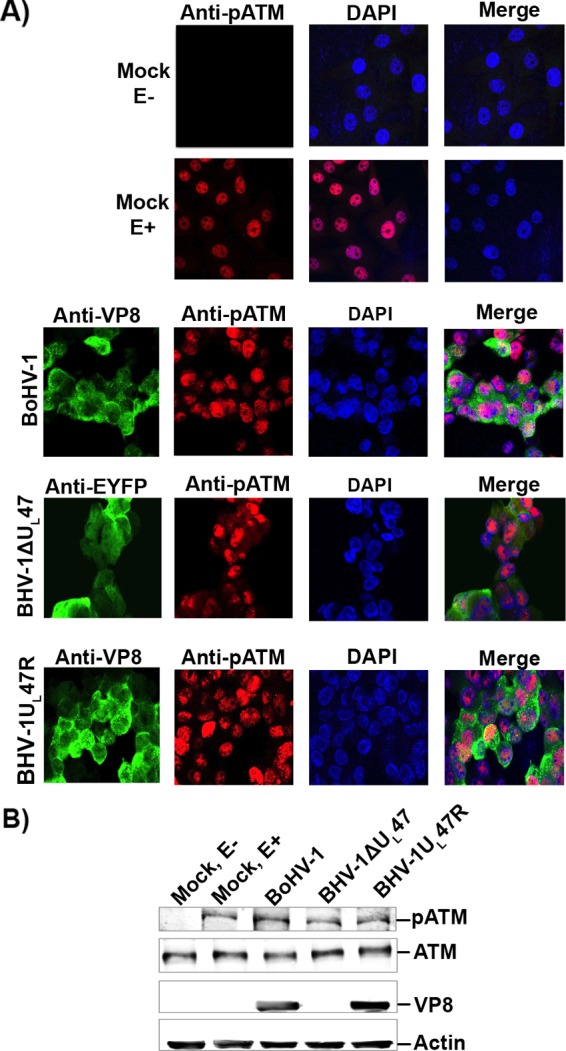

To investigate NBS1 phosphorylation in infected cells, MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, or BoHV-1UL47R. At 14 h postinfection cells were left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min, followed by incubation with a pNBS1-specific antibody. As shown in Fig. 7A, without etoposide treatment no pNBS1 was detected, while the addition of etoposide induced phosphorylation of NBS1 in mock-infected cells. However, in BoHV-1- and BoHV-1UL47R-infected cells no pNSB1 was detected, even in the presence of etoposide (Fig. 7B and D), while in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells pNBS1 was observed regardless of etoposide treatment (Fig. 7C). The lack of pNBS1 in BoHV-1- and BoHV-1UL47R-infected cells, but not in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells, was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 7E). The incoming virus particles of DNA viruses and subsequent DNA replication induce DNA damage responses to activate DNA repair proteins at early times postinfection (25, 26). This explains why BoHV-1ΔUL47 infection resulted in ATM activation and increased phosphorylation of NBS1.

FIG 7.

Phosphorylation of NBS1 is inhibited by BoHV-1 but not by BoHV-1ΔUL47. MDBK cells were mock infected (A) or infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4 (B), BoHV-1ΔUL47-EYFP at an MOI of 5 (C), or BoHV-1UL47R at an MOI of 4 (D). At 14 h postinfection, cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. Cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde, permeabilized, and incubated with murine monoclonal VP8- or EYFP-specific antibodies and rabbit pNBS1-specific antibodies. Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI. The cells were examined with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. E, etoposide. (E) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, or BoHV-1UL47R as described for panels A to D. At 14 h postinfection, mock-infected cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. Cell lysates were collected, and 50-μg aliquots of total protein of each sample were analyzed by Western blotting. NBS1, pNBS1, VP8, and actin were detected with anti-NBS1, anti-pNBS1, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively.

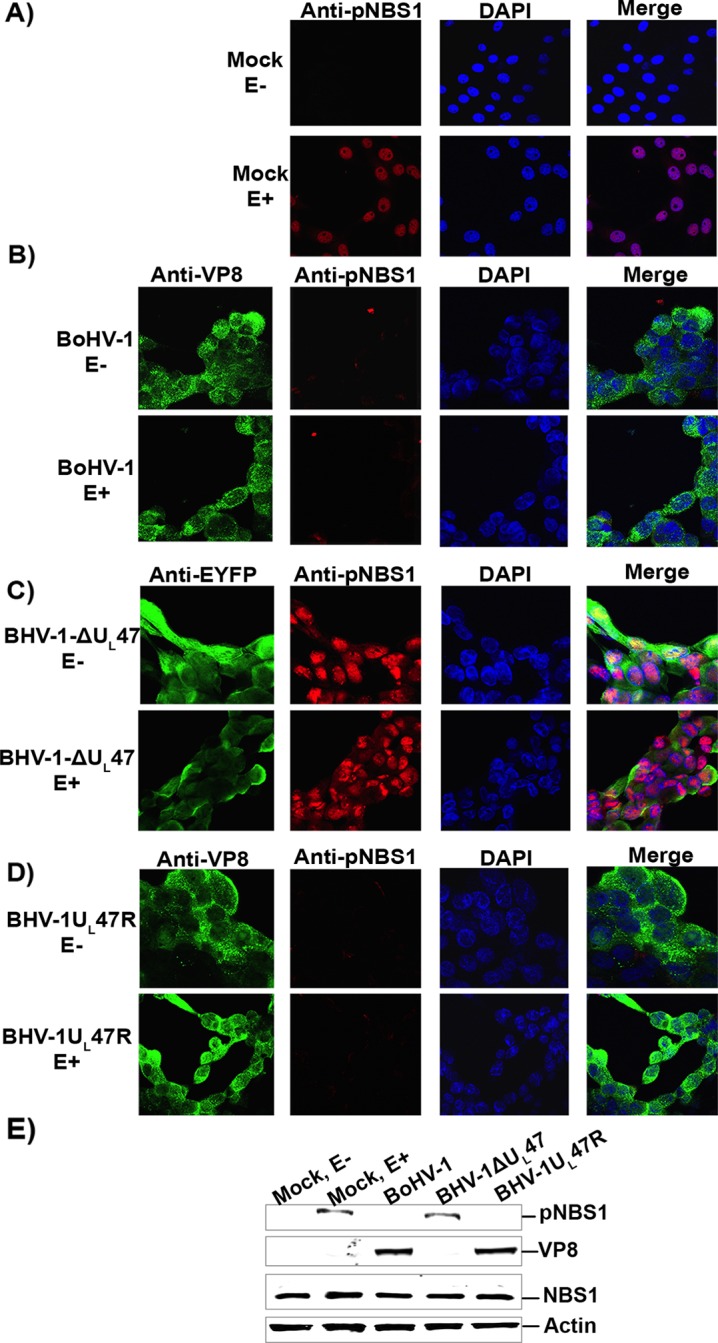

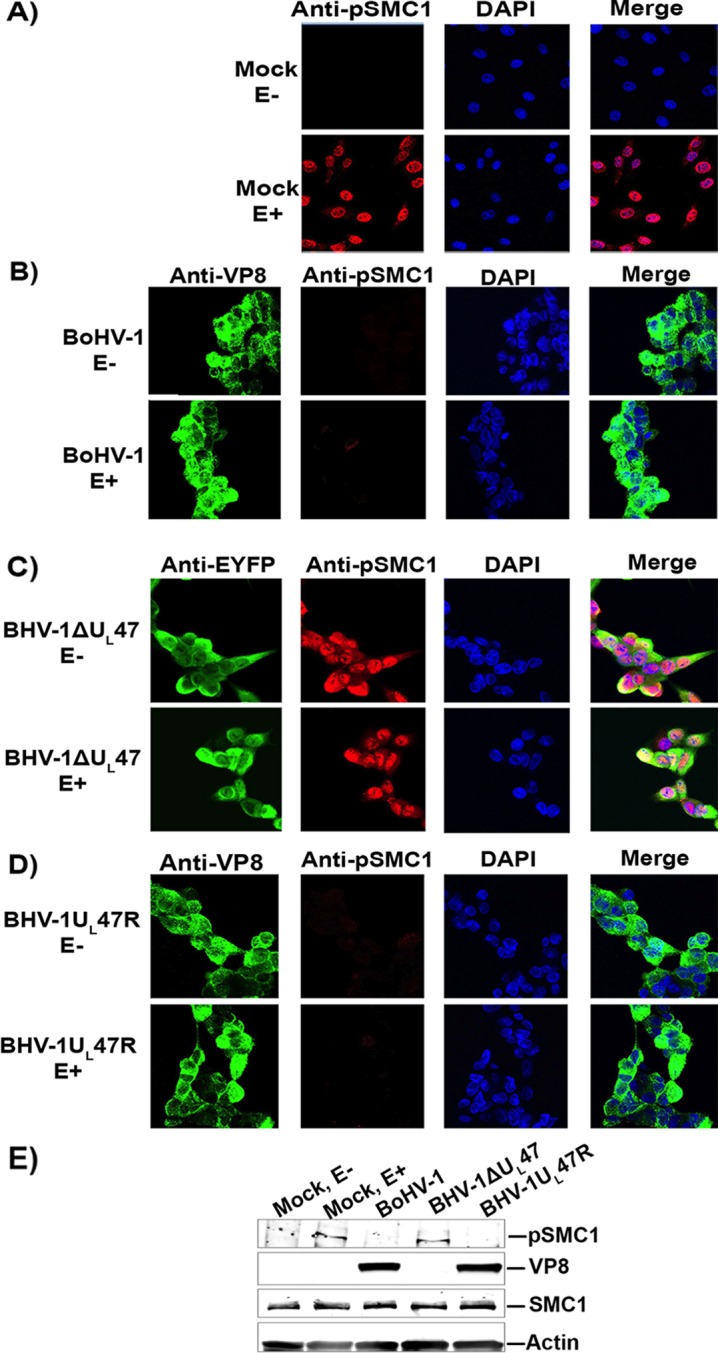

SMC1 phosphorylation during BoHV-1 infection was also investigated. MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, or BoHV-1UL47R. At 14 h postinfection, cells were left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min and then incubated with a pSMC1-specific antibody. No pSMC1 was detected without etoposide treatment, while the addition of etoposide induced phosphorylation of SMC1 in mock-infected cells (Fig. 8A). Inhibition of SMC1 phosphorylation was observed in BoHV-1 (Fig. 8B)- and BoHV-1UL47R (Fig. 8D)-infected cells, whereas SMC1 was phosphorylated in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells (Fig. 8C). This was confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 8E). These results demonstrate that BoHV-1 infection stimulates ATM activation but does not induce NBS1 phosphorylation, which consequently prevents SMC1 phosphorylation, and that VP8 is required for this function.

FIG 8.

BoHV-1, but not BoHV-1ΔUL47, inhibits phosphorylation of SMC1. MDBK cells were mock infected (A) or infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4 (B), BoHV-1ΔUL47-EYFP at an MOI of 5 (C), or BoHV-1UL47R at an MOI of 4 (D). At 14 h postinfection, cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. The cells were fixed and incubated with murine monoclonal VP8- or EYFP-specific antibodies and rabbit pSMC1-specific antibodies, followed by incubation with Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, respectively. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI. The cells were examined with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. E, etoposide. (E) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1, BoHV-1ΔUL47, or BoHV-1UL47R as described above. At 14 h postinfection, mock-infected cells were left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. Cell lysates were generated, and 50-μg aliquots of total protein of each sample were analyzed by Western blotting. SMC1, pSMC1, VP8, and actin were detected with anti-SMC1, anti-pSMC1, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively.

BoHV-1 infection inhibits phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1 early during infection.

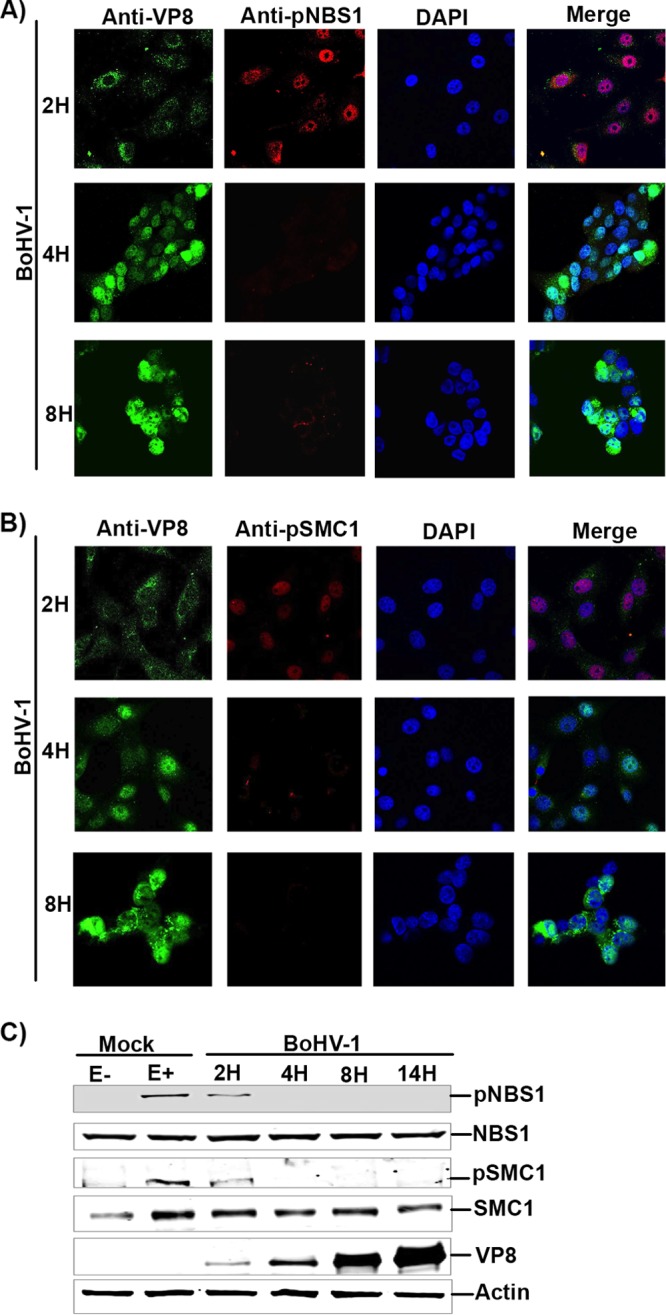

Since NBS1 phosphorylation is essential for activation of S-phase checkpoint control by activating SMC1 (6), it was of interest to investigate at which time during BoHV-1 infection VP8 interferes with NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation. MDBK cells were either mock infected or infected with BoHV-1. At 2 h postinfection VP8 was cytoplasmic due to release of virion VP8 into the cytoplasm, as previously shown (17, 18). The cytoplasmic VP8 did not inhibit phosphorylation of NBS1 or SMC1 (Fig. 9A and B). At 4 h postinfection VP8 was nuclear, and no pNBS1 was detected at this time point or at 8 h postinfection. Similarly, pSMC1 was observed at 2 h postinfection, whereas at 4 h or 8 h postinfection pSMC1 was not detected (Fig. 9B). A further analysis by Western blotting confirmed that NBS1 and SMC1 were phosphorylated at a low level at 2 h postinfection but were not phosphorylated at later time points (Fig. 9C). VP8 was detected as early as 2 h postinfection and increased in concentration at later time points due to de novo synthesis, thus inhibiting NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation. Collectively, these results indicate that nuclear VP8 inhibits NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation from 4 h onwards during BoHV-1 infection.

FIG 9.

Nuclear BoHV-1 VP8 inhibits phosphorylation of NBS1 and SMC1. (A) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4. Cells were fixed and incubated at the indicated time points with mouse monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit polyclonal anti-pNBS1 antibodies. (B) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4. Cells were fixed and incubated at the indicated time points with mouse monoclonal anti-VP8 and rabbit polyclonal anti-pSMC1 antibodies. Alexa-488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG were used as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold DAPI mounting medium. The cells were examined with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope. (C) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4. Mock cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. BoHV-1 cell lysates were collected at 2, 4, 8, and 14 h postinfection, and 50-μg aliquots of total protein of each sample were analyzed by Western blotting. NBS1, pNBS1, SMC1, pSMC1, VP8, and actin were detected with anti-NBS1, anti-pNBS1, anti-SMC1, anti-pSMC1, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively.

VP8 inhibits DNA repair.

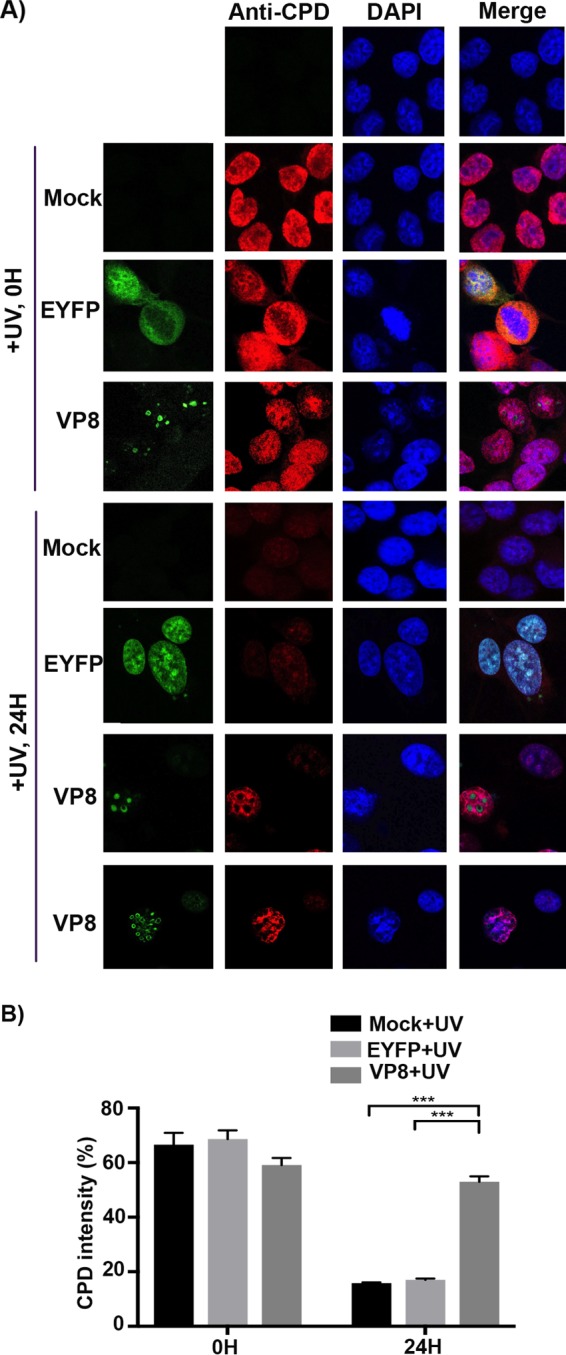

Checkpoints constitute the central cellular surveillance that coordinates DNA repair. DNA repair is controlled throughout the cell cycle (27, 28). SMC1 phosphorylation contributes to S-phase checkpoint activation and repair of damaged DNA (29). Since VP8 inhibited NBS1 and SMC1 phosphorylation, which are both involved in DNA repair, we further examined the effect of VP8 on UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD) repair. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection cells were irradiated with UV. Cells were then either fixed immediately at 0 h or further incubated for 24 h. CPDs were identified with a monoclonal anti-CPD antibody. Increased CPD intensity was observed in mock-treated and EYFP- and VP8-expressing cells immediately after UV exposure. At 24 h after UV exposure the CPDs were repaired in mock- and EYFP-transfected cells but not in VP8-expressing cells (Fig. 10A). To perform a quantitative analysis, the CPD intensity was measured in 50 cells for each sample (Fig. 10B) by using a biological image-processing program, Fiji (30). At 0 h a high level of UV-induced CPDs was observed in mock-treated and EYFP- and VP8-expressing cells. The UV-induced CPDs in mock-treated and EYFP-expressing cells were repaired after 24 h, while in VP8-expressing cells the CPD intensity did not change, indicating impairment of DNA repair in the presence of VP8.

FIG 10.

VP8 inhibits DNA repair. (A) HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP for 24 h. Cells were UV irradiated at 10 J/m2. Cells were fixed immediately after UV exposure or left to recover for 24 h and then fixed with paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized and stained with a monoclonal anti-CPD antibody, followed by incubation with Alexa-633-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG. (B) CPD fluorescence intensity was measured in 50 cells in each sample using a biological image-processing program, Fiji (30). The values of PDU are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (***, P < 0.001).

VP8 induces apoptosis.

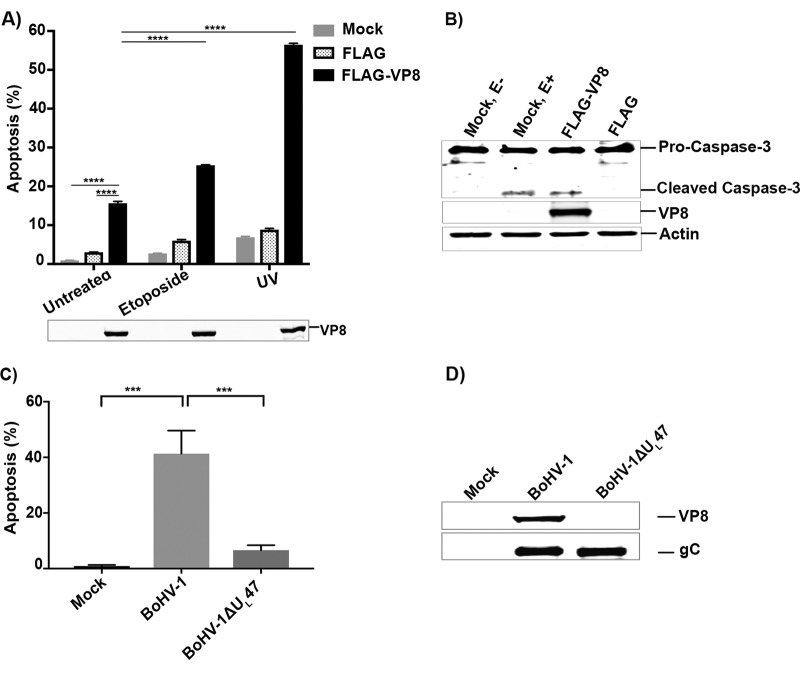

Successful virus infection involves efficient production and spread of its progeny. Viral proteins such as HIV-1 VPr protein induce apoptosis by inhibiting DNA repair (31). Recently it was shown that prevention of SMC1 phosphorylation leads to a defect in the S-phase checkpoint and decreased cell survival after induction of DNA damage (29). Since VP8 inhibited phosphorylation of SMC1, we investigated whether VP8 mediates induction of apoptosis or increases DNA damage-induced apoptosis. HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG or pFLAG-VP8. To determine the extent of apoptosis, cells were left untreated, treated with etoposide, or exposed to UV at 24 h postinfection. After 12 h of etoposide induction or UV exposure, cells were trypsinized and a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay was performed. Compared to that of untreated mock- and pFLAG-transfected cells, the level of apoptosis was higher in untreated pFLAG-VP8-transfected cells (Fig. 11A). DNA damage induction by etoposide increased apoptosis in mock- and pFLAG-transfected cells to about 3% and 6%, respectively. However, in etoposide-treated VP8-transfected cells, apoptosis was increased to 26%, which demonstrates that VP8 enhances DNA damage-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, as we observed inhibition of DNA repair by VP8 following UV treatment (Fig. 10), we examined whether VP8 enhances UV-induced apoptosis. While UV exposure of mock- and FLAG-transfected cells augmented apoptosis to 8% and 9% of cells, respectively, the percentage of apoptotic cells increased to ∼55% in UV-treated VP8-transfected cells. This further confirms that DNA damage-induced apoptosis was increased in VP8-transfected cells.

FIG 11.

VP8 induces apoptosis in transfected and BoHV-1-infected cells. (A) HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG or pFLAG-VP8. At 24 h posttransfection cells were left untreated, treated with etoposide or irradiated with UV 50 J/m2, and incubated for 12 h before trypsinization. Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL assay. The cells were analyzed by FACS. (B) HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG or pFLAG-VP8. At 48 h posttransfection, mock-infected cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide. Cell lysates were collected, and equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by Western blotting. Caspase-3, cleaved caspase-3, VP8, and actin were detected with anti-caspase-3, anti-VP8, and anti-actin antibodies, respectively. (C) MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47 at an MOI of 4. At 10 h postinfection, cells were trypsinized and apoptosis was measured by TUNEL assay. The cells were analyzed by FACS. (D) Cell lysates were generated, and VP8 and glycoprotein C (gC) were detected with murine monoclonal anti-VP8 and anti-rabbit polyclonal gC antibodies, followed by incubation with IRDye 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, respectively.

It has been reported that caspase 3 is activated in response to unrepaired UV-induced DNA damage (32). To determine whether VP8 expression leads to cleavage of caspase-3, cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-VP8 or pFLAG. An antibody that detects both the procaspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 was used for detection. In VP8-expressing cells as well as in mock-transfected cells treated with etoposide, cleaved caspase-3 was detected. However, cleaved caspase-3 was not detected in mock- and FLAG-transfected cells (Fig. 11B). This indicates that VP8 can activate caspase-3, in agreement with the fact that BoHV-1 infection activates caspase-3 to induce apoptosis (33, 34).

We also examined the role of VP8 in the induction of apoptosis in virus-infected cells. MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47. Cells were trypsinized, and a TUNEL assay was performed. As shown in Fig. 11C, in contrast to mock infection, BoHV-1 infection caused apoptosis in 40% of the cells. However, the number of apoptotic cells was 8% in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells. Expression of VP8 in BoHV-1-infected cells was confirmed in Fig. 11D. To confirm infection with BoHV-1ΔUL47, expression of glycoprotein C (gC) was demonstrated (Fig. 11D). The residual apoptosis in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells could be the result of the virus attachment process, which was previously shown to induce apoptosis in BoHV-1-infected cells (35). Furthermore, gD was suggested to be involved in the induction of apoptosis (36), as was as the immediate-early protein of BoHV-1, bICP0 (37). Since BoHV-1ΔUL47 contains gD and bICP0, the residual apoptotic activity in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells is likely due to one or both of these proteins. A significant reduction (∼32%) of apoptosis was observed in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells compared to that of wild-type BoHV-1 infection, which demonstrates that VP8 contributes to induction of apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

During virus infection, host cells establish an intrinsic antiviral defense, such as the IFN response and apoptosis. While some viruses counteract these responses by modulating the host immune responses, others manipulate the cellular machinery in favor of virus replication. In the present study, we demonstrated that VP8 interacts with ATM and NBS1. ATM is a central player in the DNA damage response and is activated immediately after DNA damage (3) by autophosphorylation at Serine-1981, which in turn leads to the phosphorylation of many downstream targets to coordinate DNA repair, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis (reviewed in reference 3). Although VP8 interacted with ATM, VP8 did not interfere with ATM phosphorylation. However, although the ATM activation was not interrupted, VP8 inhibited NBS1 phosphorylation. VP8, ATM, and NBS1 were detected as a complex, indicating that VP8 interacts with both ATM and NBS1. Since interaction between NBS1 and ATM is required for NBS1 phosphorylation, VP8 might inhibit phosphorylation by blocking this interaction. Phosphorylation of SMC1 by ATM depends on NBS1 phosphorylation and is critical to activate the S-phase checkpoint (6). In fact, VP8 also inhibited SMC1 phosphorylation, which can prevent S-phase checkpoint activation (6, 29). Overall, this shows that VP8 interacts with DNA damage response proteins and disrupts the ATM/NBS1/SMC1 pathway, resulting in a defective DNA damage response.

BoHV-1, but not BoHV-1ΔUL47, inactivated the ATM/NBS1 pathway by reducing phosphorylation of NBS1, further supporting this function of VP8. Inhibition of NBS1 phosphorylation was mediated by nuclear VP8 from 4 h onwards during infection. In contrast to BoHV-1, HSV-1 does not disrupt the ATM signaling pathway. Interestingly, Lou et al. revealed that in two closely related species, such as white-cheeked gibbon (Nomascus leucogenys) and siamang (Symphalangus syndactylus), NBS1 functions differently during the establishment of HSV-1 infection (38), supporting the possibility of a distinctive NBS1 role in the establishment of herpesvirus infections. Moreover, unlike HSV-1, HCMV disrupts both ATM and ATR pathways to subvert full activation of S-phase checkpoints (39), and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus inhibits the ATM signal transduction pathway by compromising the ATM/P53 DNA damage response checkpoint (40).

Viruses have developed unique strategies to circumvent host cell responses, while others hijack cellular DNA damage response proteins for their propagation or replication. Similar to BoHV-1, homologous recombination repair is also inhibited during HSV-1 infection (41). Furthermore, murine gamma herpesvirus 68 (γHV68) M2 protein interacts with the DNA repair complex, DDB1/ATM/COP9/cullin (14). Although γHV68 M2 protein induced ATM activation, the DNA damage response was abolished. Adenovirus E4 protein also reorganizes the MRN complex, resulting in degradation (42). Adenovirus deregulates the host cell machinery in favor of viral genome processing, whereas HSV-1 activates and manipulates the DNA damage response. Thus, viral proteins use various distinct and overlapping mechanisms to accomplish viral propagation.

Nonrepaired DNA induces apoptosis in DNA repair-deficient cells (43). Similarly, inhibition of DNA repair has been implicated in the induction of apoptosis by HIV VPr (31). Previously, BoHV-1 has been shown to induce apoptosis (35, 37, 44). Interestingly, VP8 appeared to contribute to induction of apoptosis outside the context of infection as well as during BoHV-1 infection. We observed higher apoptosis in BoHV-1-infected cells than in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells. A low level of apoptosis was still observed in BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells, which can be contributed to other BoHV-1 proteins, for instance, gD (36), ORF8 (44), and/or bICP0 (37). Since, according to previous reports, prevention of SMC1 phosphorylation leads to a defect in the S-phase checkpoint and decreased cell survival after induction of DNA damage (29), prevention of SMC1 phosphorylation and abrogation of DNA repair by VP8 likely contributes to induction of apoptosis. Alternatively, VP8 may contribute to ATM activation, which can then phosphorylate P53 (thus leading to apoptosis). However, we observed activation of caspase 3 by VP8, and Dunkern et al. demonstrated that in repair-deficient cells UV-induced DNA damage triggered apoptosis independent of p53 and through caspase 3 activation (32). The fact that previously caspase-3-mediated apoptosis was observed in BoHV-1-infected cells (33, 34) further supports the contention that VP8 functions through caspase 3 activation to induce apoptosis.

While some viruses express antiapoptotic proteins to favor viral pathogenesis, others also exhibit proapoptotic properties to manipulate the cellular machinery for efficient virus production. For example, influenza virus upregulates proapoptotic factors for viral replication (45, 46), and HIV-1 enhances proapoptotic gene expression for efficient virus production (47). Furthermore, HSV-1 immediate-early protein ICP0 triggers apoptosis during HSV-1 infection to influence viral pathogenesis (48). Induction of apoptosis by VP8 might expedite the egress and progression of BoHV-1 infection. In BoHV-1ΔUL47-infected cells, the release of infectious virus particles into the culture medium was reduced more than 1,000-fold compared to that of BoHV-1-infected cells, which suggested reduced egress of BoHV-1ΔUL47 virions (16).

In summary, BoHV-1 developed a novel evasion mechanism, whereby VP8 targets DNA damage response proteins. Without interfering with ATM activation, VP8 abrogated downstream signaling and thus impaired the DNA repair mechanism. As a consequence, VP8 increased DNA damage-induced apoptosis. VP8 is the first BoHV-1 tegument protein reported to interfere with the DNA damage response pathway. These results illustrate a potential role of VP8 in the modulation of DNA damage response during BoHV-1 infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, viruses, and plasmids.

HeLa, MDBK, and HEK 293T cells were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (MEM; Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Ltd., Oakville, ON, Canada). The medium was supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Life Technologies), and 10 mM HEPES buffer (Life Technologies). Cells were cultured with 5% CO2 in a 37°C incubator. BoHV-1 108, BoHV-1ΔUL47, and BoHV-1UL47R were propagated in MDBK cells (16). MDBK cells were infected with BoHV-1 at different multiplicities of infection (MOI), as mentioned elsewhere. The plasmids pFLAG and pFLAG-VP8 were previously described by Labiuk et al. (49) and Afroz et al. (18), respectively. EYFP was amplified from pEYFP by using forward primer 5′-CACAAGCTTCCACCGGTCGCCACCAT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGACTCGAGCGTGGGAGGTTTTTTAAAGCAAG-3′. pFLAG-VP8 and the amplified EYFP were digested with HindIII and XhoI, followed by ligation, to generate pFLAG-EYFP.

Antibodies and chemical reagents.

VP8-specific murine monoclonal and glycoprotein C-specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used as previously described (18). ATM-, pATM-, NBS1-, pNBS1-, SMC1-, and pSMC1-specific antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Toronto, ON, Canada). Murine monoclonal actin- and FLAG-specific antibodies were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Ltd. Mouse monoclonal CPD-specific antibody was obtained from Cosmobio, Tokyo, Japan. Rabbit caspase-3-specific antibody was obtained from New England BioLabs. Etoposide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Ltd.

Preparation of cell lysates.

HEK 293T and HeLa cells were transfected at 60 to 80% confluence with different plasmids. Lipofectamine and Plus reagents (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) were used for transfection. At 24 h posttransfection, HEK 293T cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). Cells were treated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) supplemented with mammalian cell and tissue extract protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and gently rocked on a nutator for 5 min, followed by incubation on ice for 30 min. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were collected in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes and kept at −80°C for future use. MDBK cells were lysed as described above.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were generated as described above. Cell lysates were added to anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich), and the mixtures were incubated overnight at 4°C; alternatively, cell lysates were incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies, followed by incubation for 3 h at 4°C with protein G Sepharose Fast Flow beads (GE Health Care, Niskayuna, NY, USA). The immune complexes were washed with wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 250 mM NaCl, 2% Triton X-100, pH 7.4) and subsequently boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min. The immune complexes were then separated on 10% or 8% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. The nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS containing Tween 20 (PBST; 3.2 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) for 2 h, followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with PBST, followed by incubation with IRDye 680-conjugated anti-mouse IgG or IRDye 800CW-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA). An Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system (LI-COR Bioscience) was used for protein detection, and the images were processed using the Odyssey 3.0.16 application software (LI-COR Bioscience).

Immunofluorescence.

HeLa cells were plated at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells per well in two-chamber Permanox slides (Lab-Tek, Naperville, IL, USA). Cells were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG-EYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at room temperature (RT) and permeabilized, followed by blocking with 1% goat serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. MDBK cells were infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV1-UL47R at an MOI of 4 or with BoHV1-ΔUL47 at an MOI of 5 for 14 h. The cells were either left untreated or were treated with etoposide for 30 min, followed by fixation and antibody incubations as described above. For the time course experiment, MDBK cells were infected with BoHV-1 at an MOI of 4, and the cells were fixed at the indicated time points and blocked overnight, followed by incubation with primary antibodies. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG or Alexa Fluor 633 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) for 1 h. Mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to identify the nucleus, and the slides were air dried for 24 h at room temperature. The cells were examined by using laser excitation at 488 nm (Alexa 488), 633 nm (Alexa 633), and 461 nm (DAPI). Confocal images were taken with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Concord, ON, Canada). Image J software was used to process the images.

Cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer identification.

HeLa cells were mock transfected or transfected with pEYFP or pVP8-EYFP. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were irradiated with 10 J/m2 UV-C. Cells were treated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were either fixed with 4% formalin immediately after UV irradiation at 0 h or incubated for 24 h before fixation. The cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 followed by blocking with 20% FBS. The cells were then incubated with murine monoclonal anti-CPD antibody (Cosmo Bio Co., Japan) for 1.5 h at 37°C. The cells were washed 5 times with PBS and were then incubated with Alexa-Fluor 633 goat anti-mouse IgG. The images were captured with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc.) and processed with Image J software. A biological image-processing program, Fiji (30), was used to quantify the relative fluorescent intensities. The mean intensity within defined areas was shown as procedure defined unit (PDU).

Apoptosis assay.

HeLa cells at 60 to 70% confluence were mock transfected or transfected with pFLAG or pFLAG-VP8. At 24 h posttransfection cells were left untreated, treated with etoposide, or exposed to UV and incubated for another 12 h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde, followed by addition of 70% ethanol, and stored at −20°C overnight. The cells were analyzed by using an APO-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) TUNEL assay kit (Molecular Probes, Thermofisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cells were washed with the washing buffer before incubation with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase and 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine 5-triphosphate at 37°C for 2 h. Cells were washed three times, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488 dye-labeled anti-BrdU antibody. After subsequent washes, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). All data were analyzed with Kaluza software (v1.2) (Beckman Coulter Inc., Pasadena, CA, USA). Similarly, MDBK cells were mock infected or infected with BoHV-1 or BoHV-1ΔUL47 at the indicated MOIs, and the TUNEL assay was performed as described above.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Yurij Popowych for his assistance in FACS cell sorting.

This research was supported by grant 90887-2010 RGPIN from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. S.A. was partially supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Training Grant in Health Research Using Synchrotron Techniques (CIHR-THRUST).

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. 2000. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elledge SJ. 1996. Cell cycle checkpoints: preventing an identity crisis. Science 274:1664–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JH, Paull TT. 2007. Activation and regulation of ATM kinase activity in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Oncogene 26:7741–7748. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakkenist CJ, Kastan MB. 2003. DNA damage activates ATM through intermolecular autophosphorylation and dimer dissociation. Nature 421:499–506. doi: 10.1038/nature01368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim DS, Kim ST, Xu B, Maser RS, Lin J, Petrini JH, Kastan MB. 2000. ATM phosphorylates p95/nbs1 in an S-phase checkpoint pathway. Nature 404:613–617. doi: 10.1038/35007091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yazdi PT, Wang Y, Zhao S, Patel N, Lee EY, Qin J. 2002. SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint. Genes Dev 16:571–582. doi: 10.1101/gad.970702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aita K, Irie H, Koyama AH, Fukuda A, Yoshida T, Shiga J. 2001. Acute adrenal infection by HSV-1: role of apoptosis in viral replication. Arch Virol 146:2009–2020. doi: 10.1007/s007050170048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheldrick P, Laithier M, Lando D, Ryhiner ML. 1973. Infectious DNA from herpes simplex virus: infectivity of double-stranded and single-stranded molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 70:3621–3625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.12.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jongeneel CV, Bachenheimer SL. 1981. Structure of replicating herpes simplex virus DNA. J Virol 39:656–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Chiara G, Racaniello M, Mollinari C, Marcocci ME, Aversa G, Cardinale A, Giovanetti A, Garaci E, Palamara AT, Merlo D. 2016. Herpes simplex virus-type 1 (HSV-1) impairs DNA repair in cortical neurons. Front Aging Neurosci 8:242. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirata N, Kudoh A, Daikoku T, Tatsumi Y, Fujita M, Kiyono T, Sugaya Y, Isomura H, Ishizaki K, Tsurumi T. 2005. Activation of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated DNA damage checkpoint signal transduction elicited by herpes simplex virus infection. J Biol Chem 280:30336–30341. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh VV, Dutta D, Ansari MA, Dutta S, Chandran B. 2014. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus induces the ATM and H2AX DNA damage response early during de novo infection of primary endothelial cells, which play roles in latency establishment. J Virol 88:2821–2834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03126-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarakanova VL, Leung-Pineda V, Hwang S, Yang CW, Matatall K, Basson M, Sun R, Piwnica-Worms H, Sleckman BP, Virgin HWT. 2007. Gamma-herpesvirus kinase actively initiates a DNA damage response by inducing phosphorylation of H2AX to foster viral replication. Cell Host Microbe 1:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang X, Pickering MT, Cho NH, Chang H, Volkert MR, Kowalik TF, Jung JU. 2006. Deregulation of DNA damage signal transduction by herpesvirus latency-associated M2. J Virol 80:5862–5874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02732-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng C, Brownlie R, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2004. Characterization of nuclear localization and export signals of the major tegument protein VP8 of bovine herpesvirus-1. Virology 324:327–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lobanov VA, Maher-Sturgess SL, Snider MG, Lawman Z, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2010. A UL47 gene deletion mutant of bovine herpesvirus type 1 exhibits impaired growth in cell culture and lack of virulence in cattle. J Virol 84:445–458. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01544-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasilenko NL, Snider M, Labiuk SL, Lobanov VA, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2012. Bovine herpesvirus-1 VP8 interacts with DNA damage binding protein-1 (DDB1) and is monoubiquitinated during infection. Virus Res 167:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Afroz S, Brownlie R, Fodje M, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2016. VP8, the major tegument protein of bovine herpesvirus 1, interacts with cellular STAT1 and inhibits interferon beta signaling. J Virol 90:4889–4904. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00017-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salsman J, Jagannathan M, Paladino P, Chan PK, Dellaire G, Raught B, Frappier L. 2012. Proteomic profiling of the human cytomegalovirus UL35 gene products reveals a role for UL35 in the DNA repair response. J Virol 86:806–820. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05442-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiloh Y, Rotman G. 1996. Ataxia-telangiectasia and the ATM gene: linking neurodegeneration, immunodeficiency, and cancer to cell cycle checkpoints. J Clin Immunol 16:254–260. doi: 10.1007/BF01541389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CK, Jeng KS, Machida K, Cheng YS, Lai MM. 2008. Hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protein interacts with ATM, impairs DNA repair and enhances sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Virology 370:295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caldecott K, Banks G, Jeggo P. 1990. DNA double-strand break repair pathways and cellular tolerance to inhibitors of topoisomerase II. Cancer Res 50:5778–5783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney JP, Maser RS, Olivares H, Davis EM, Le Beau M, Yates JR III, Hays L, Morgan WF, Petrini JH. 1998. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell 93:477–486. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu J, Petersen S, Tessarollo L, Nussenzweig A. 2001. Targeted disruption of the Nijmegen breakage syndrome gene NBS1 leads to early embryonic lethality in mice. Curr Biol 11:105–109. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turnell AS, Grand RJ. 2012. DNA viruses and the cellular DNA-damage response. J Gen Virol 93:2076–2097. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lilley CE, Chaurushiya MS, Boutell C, Everett RD, Weitzman MD. 2011. The intrinsic antiviral defense to incoming HSV-1 genomes includes specific DNA repair proteins and is counteracted by the viral protein ICP0. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002084. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Branzei D, Foiani M. 2008. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hustedt N, Durocher D. 2016. The control of DNA repair by the cell cycle. Nat Cell Biol 19:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitagawa R, Bakkenist CJ, McKinnon PJ, Kastan MB. 2004. Phosphorylation of SMC1 is a critical downstream event in the ATM-NBS1-BRCA1 pathway. Genes Dev 18:1423–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1200304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schrofelbauer B, Hakata Y, Landau NR. 2007. HIV-1 Vpr function is mediated by interaction with the damage-specific DNA-binding protein DDB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:4130–4135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610167104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunkern TR, Fritz G, Kaina B. 2001. Ultraviolet light-induced DNA damage triggers apoptosis in nucleotide excision repair-deficient cells via Bcl-2 decline and caspase-3/-8 activation. Oncogene 20:6026–6038. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devireddy LR, Jones CJ. 1999. Activation of caspases and p53 by bovine herpesvirus 1 infection results in programmed cell death and efficient virus release. J Virol 73:3778–3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Zhang K, Huang Y, Ding L, Chen G, Zhang H, Tong D. 2012. Bovine herpes virus type 1 induces apoptosis through Fas-dependent and mitochondria-controlled manner in Madin-Darby bovine kidney cells. Virol J 9:202. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanon E, Meyer G, Vanderplasschen A, Dessy-Doize C, Thiry E, Pastoret PP. 1998. Attachment but not penetration of bovine herpesvirus 1 is necessary to induce apoptosis in target cells. J Virol 72:7638–7641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanon E, Keil G, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S, Griebel P, Vanderplasschen A, Rijsewijk FA, Babiuk L, Pastoret PP. 1999. Bovine herpesvirus 1-induced apoptotic cell death: role of glycoprotein D. Virology 257:191–197. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henderson G, Zhang Y, Inman M, Jones D, Jones C. 2004. Infected cell protein 0 encoded by bovine herpesvirus 1 can activate caspase 3 when overexpressed in transfected cells. J Gen Virol 85:3511–3516. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lou DI, Kim ET, Meyerson NR, Pancholi NJ, Mohni KN, Enard D, Petrov DA, Weller SK, Weitzman MD, Sawyer SL. 2016. An intrinsically disordered region of the DNA repair protein Nbs1 is a species-specific barrier to herpes simplex virus 1 in primates. Cell Host Microbe 20:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo MH, Rosenke K, Czornak K, Fortunato EA. 2007. Human cytomegalovirus disrupts both ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM)- and ATM-Rad3-related kinase-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic infection. J Virol 81:1934–1950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01670-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shin YC, Nakamura H, Liang X, Feng P, Chang H, Kowalik TF, Jung JU. 2006. Inhibition of the ATM/p53 signal transduction pathway by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus interferon regulatory factor 1. J Virol 80:2257–2266. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2257-2266.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith S, Weller SK. 2015. HSV-I and the cellular DNA damage response. Future Virol 10:383–397. doi: 10.2217/fvl.15.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stracker TH, Carson CT, Weitzman MD. 2002. Adenovirus oncoproteins inactivate the Mre11-Rad50-NBS1 DNA repair complex. Nature 418:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature00863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dunkern TR, Kaina B. 2002. Cell proliferation and DNA breaks are involved in ultraviolet light-induced apoptosis in nucleotide excision repair-deficient Chinese hamster cells. Mol Biol Cell 13:348–361. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamichi K, Matsumoto Y, Otsuka H. 2002. Bovine herpesvirus 1 U(S) ORF8 protein induces apoptosis in infected cells and facilitates virus egress. Virology 304:24–32. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wurzer WJ, Ehrhardt C, Pleschka S, Berberich-Siebelt F, Wolff T, Walczak H, Planz O, Ludwig S. 2004. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and Fas/FasL is crucial for efficient influenza virus propagation. J Biol Chem 279:30931–30937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wurzer WJ, Planz O, Ehrhardt C, Giner M, Silberzahn T, Pleschka S, Ludwig S. 2003. Caspase 3 activation is essential for efficient influenza virus propagation. EMBO J 22:2717–2728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Ragupathy V, Zhao J, Hewlett I. 2011. Molecules from apoptotic pathways modulate HIV-1 replication in Jurkat cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414:20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanfilippo CM, Blaho JA. 2006. ICP0 gene expression is a herpes simplex virus type 1 apoptotic trigger. J Virol 80:6810–6821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00334-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Labiuk SL, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk S. 2009. Major tegument protein VP8 of bovine herpesvirus 1 is phosphorylated by viral US3 and cellular CK2 protein kinases. J Gen Virol 90:2829–2839. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.013532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]