A critical barrier to developing a cure for HIV-1 infection is the long-lived viral reservoir that exists in resting CD4+ T cells, the main targets of HIV-1. The viral reservoir is maintained through a variety of mechanisms, including regulation of the HIV-1 LTR promoter. The host protein SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 replication in nondividing cells, but its role in HIV-1 latency remains unknown. Here we report a new function of SAMHD1 in regulating HIV-1 latency. We found that SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 LTR promoter-driven gene expression and reactivation of viral latency in cell lines and primary CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, SAMHD1 bound to the HIV-1 LTR in vitro and in a latently infected CD4+ T-cell line, suggesting that the binding may negatively modulate reactivation of HIV-1 latency. Our findings indicate a novel role for SAMHD1 in regulating HIV-1 latency, which enhances our understanding of the mechanisms regulating proviral gene expression in CD4+ T cells.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, SAMHD1, LTR, gene expression, latency, reactivation

ABSTRACT

Sterile alpha motif and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) restricts human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication in nondividing cells by degrading intracellular deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs). SAMHD1 is highly expressed in resting CD4+ T cells, which are important for the HIV-1 reservoir and viral latency; however, whether SAMHD1 affects HIV-1 latency is unknown. Recombinant SAMHD1 binds HIV-1 DNA or RNA fragments in vitro, but the function of this binding remains unclear. Here we investigate the effect of SAMHD1 on HIV-1 gene expression and reactivation of viral latency. We found that endogenous SAMHD1 impaired HIV-1 long terminal repeat (LTR) activity in monocytic THP-1 cells and HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected primary CD4+ T cells. Overexpression of wild-type (WT) SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression at a transcriptional level. Tat coexpression abrogated SAMHD1-mediated suppression of HIV-1 LTR-driven luciferase expression. SAMHD1 overexpression also suppressed the LTR activity of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), but not that of murine leukemia virus (MLV), suggesting specific suppression of retroviral LTR-driven gene expression. WT SAMHD1 bound to proviral DNA and impaired reactivation of HIV-1 gene expression in latently infected J-Lat cells. In contrast, a nonphosphorylated mutant (T592A) and a dNTP triphosphohydrolase (dNTPase) inactive mutant (H206D R207N [HD/RN]) of SAMHD1 failed to efficiently suppress HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression and reactivation of latent virus. Purified recombinant WT SAMHD1, but not the T592A and HD/RN mutants, bound to fragments of the HIV-1 LTR in vitro. These findings suggest that SAMHD1-mediated suppression of HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression potentially regulates viral latency in CD4+ T cells.

IMPORTANCE A critical barrier to developing a cure for HIV-1 infection is the long-lived viral reservoir that exists in resting CD4+ T cells, the main targets of HIV-1. The viral reservoir is maintained through a variety of mechanisms, including regulation of the HIV-1 LTR promoter. The host protein SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 replication in nondividing cells, but its role in HIV-1 latency remains unknown. Here we report a new function of SAMHD1 in regulating HIV-1 latency. We found that SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 LTR promoter-driven gene expression and reactivation of viral latency in cell lines and primary CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, SAMHD1 bound to the HIV-1 LTR in vitro and in a latently infected CD4+ T-cell line, suggesting that the binding may negatively modulate reactivation of HIV-1 latency. Our findings indicate a novel role for SAMHD1 in regulating HIV-1 latency, which enhances our understanding of the mechanisms regulating proviral gene expression in CD4+ T cells.

INTRODUCTION

Sterile alpha motif and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) is the only identified mammalian deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase (dNTPase) (1, 2) with a well-characterized role in the downregulation of intracellular deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) levels (3), a mechanism by which SAMHD1 acts as a restriction factor against infection by retroviruses (4, 5) and several DNA viruses (6–10) in nondividing myeloid cells (11, 12) and quiescent CD4+ T cells (13, 14). Additionally, in vitro studies indicate that SAMHD1 is a single-stranded (ss) nucleic acid (NA) binding protein (15–18), although the function of this binding activity in cells remains unknown. One report suggested that SAMHD1 uses its RNA binding potential to exert an RNase activity against HIV-1 genomic RNA (19); however, recent studies do not support this observation (20–23).

SAMHD1 restricts retroviral replication in dividing cells less efficiently, due to the phosphorylation of SAMHD1 at Thr 592 (T592) (24–29). The dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 requires the catalytic H206 and D207 residues of the HD domain (30, 31). While mutations of either H206 or D207 abrogated ssDNA binding in vitro (15), the effect of nonphosphorylated T592 on ssDNA binding has not been described. The binding of ssNA occurs at the dimer-dimer interface on free monomers and dimers of SAMHD1. This interaction prevents the formation of catalytically active tetramers (18), suggesting a dynamic mechanism whereby SAMHD1 may regulate its potent dNTPase activity through NA binding. However, the effect of SAMHD1–NA binding on HIV-1 infection or viral gene expression is unknown.

HIV-1 latency occurs postintegration, when a proviral reservoir is formed within a population of resting memory CD4+ T cells (32). By forming a stable reservoir and preventing immune clearance of infection, HIV-1 is able to persist in the host despite effective treatment with antiretroviral therapy (33). Although HIV-1 proviral DNA is transcriptionally silent in latently infected CD4+ T cells, reactivation of intact provirus can result in the production of infectious virions (34, 35). There are several mechanisms that contribute to HIV-1 latency, including sequestration of host transcription factors in the cytoplasm and transcriptional repression (32, 35). The 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) promoter of HIV-1 proviral DNA contains several cellular transcription factor-binding sites, with transcription factors activated by external stimuli to enhance HIV-1 gene expression (36). Known cellular reservoirs of latent HIV-1 proviral DNA include quiescent CD4+ T cells and macrophages (37–39). Although HIV-1 does not productively replicate in resting CD4+ T cells, a stable state of latent infection does exist in these cells (40, 41). SAMHD1 blocks reverse transcription leading to HIV-1 restriction in resting CD4+ T cells (13, 14); however, whether SAMHD1 affects the reactivation of HIV-1 proviral DNA in latently infected CD4+ T cells remains unknown.

In this study, we demonstrate that SAMHD1 suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression and binds to the LTR promoter in a latently infected cell line model. Furthermore, endogenous SAMHD1 suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in monocytic THP-1 cells and viral reactivation in latently infected primary CD4+ T cells. Our findings suggest that SAMHD1-mediated suppression of HIV-1 gene expression contributes to the regulation of viral latency in primary CD4+ T cells, thereby identifying a novel role of SAMHD1 in modulating HIV-1 infection.

(This article was submitted to an online preprint archive [42]).

RESULTS

Exogenous SAMHD1 expression suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in HEK293T cells.

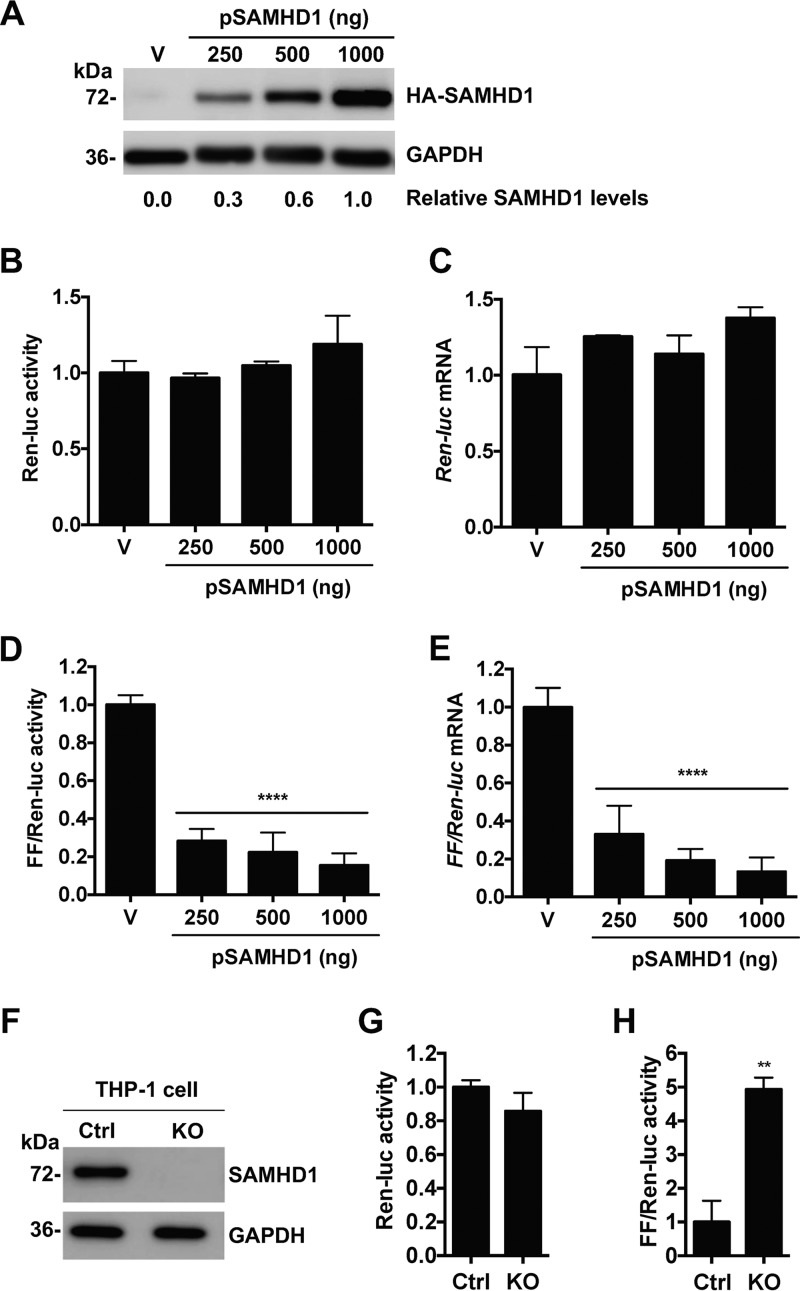

Transcriptional activation of the HIV-1 provirus is regulated by interactions between the LTR promoter and several host and viral proteins (36). However, the effect of SAMHD1 expression on HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression is unknown. To address this question, we performed an HIV-1 LTR-driven firefly luciferase (FF-Luc) reporter assay using HEK293T cells. To examine transfection efficiency, a Renilla luciferase (Ren-Luc) reporter driven by the herpes simplex virus (HSV) thymidine kinase (TK) promoter was used as a control (43). Expression of increasing levels of exogenous SAMHD1 did not change Ren-Luc protein or mRNA expression (Fig. 1A to C), indicating that transfection efficiencies were comparable among different samples and that SAMHD1 overexpression did not affect TK promoter-driven gene expression. In contrast, when normalized with the Ren-Luc control and compared to that of an empty vector, SAMHD1 expression resulted in 70 to 85% suppression of FF-Luc activity (Fig. 1D) and FF-luc mRNA levels (Fig. 1E) in a dose-dependent manner. These data suggest that exogenous SAMHD1 expression suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression at the level of gene transcription.

FIG 1.

SAMHD1 suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven luciferase expression. (A to E) An HIV-1 LTR-driven firefly luciferase (FF-Luc) construct was cotransfected with an empty vector (V) or increasing amounts of a plasmid encoding HA-tagged SAMHD1 (pSAMHD1) into HEK293T cells. Cotransfection of a construct encoding HSV TK-driven Renilla luciferase (Ren-Luc) was used as a control of transfection efficiency. (A) Overexpression of SAMHD1 was confirmed by immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Relative SAMHD1 expression levels were quantified by densitometry and normalized to GAPDH levels, with 1,000 ng of the pSAMHD1 sample set as 1. (B through E) Ren-Luc activity (B) and mRNA levels (C), and FF-Luc activity (D) and mRNA levels (E), were measured at 24 h posttransfection. (B) Ren-Luc activity was normalized to the total protein concentration. (D and E) FF-Luc activity and mRNA levels were normalized to Ren-Luc activity and mRNA levels, with vector levels set as 1. Error bars show standard deviations for at least three independent experiments as analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison posttest. Asterisks indicate significant differences (****, P ≤ 0.0001) from results for vector control cells. (F to H) FF-Luc and Ren-Luc constructs were expressed by nucleofection in THP-1 control (Ctrl) cells or SAMHD1 knockout (KO) cells. (F) SAMHD1 KO was confirmed by immunoblotting, with GAPDH used as a loading control. (G and H) Luciferase activity was measured at 48 h postnucleofection. Raw Ren-Luc values were normalized to total protein levels (G), and FF-Luc activity was normalized to Ren-Luc activity (H). Asterisks indicate significant differences (**, P ≤ 0.01) from results for control cells.

SAMHD1 silencing in THP-1 cells enhances HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression.

To determine whether endogenous SAMHD1 can suppress LTR-driven gene expression in cells, we performed the HIV-1 LTR reporter assay using human monocytic THP-1 cells expressing a high level of endogenous SAMHD1 (control) or with SAMHD1 knockout (KO) (29). THP-1 control or KO cells were nucleofected with plasmids expressing FF-Luc and Ren-Luc. The lack of SAMHD1 expression in THP-1 KO cells was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1F). In agreement with the results from HEK293T cells, Ren-Luc activity was unchanged in THP-1 control and KO cells, confirming comparable transfection (Fig. 1G). When normalized with Ren-Luc activity, KO cells showed a 4.5-fold increase in FF-Luc activity over that in control cells (Fig. 1H), indicating that endogenous SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in THP-1 cells.

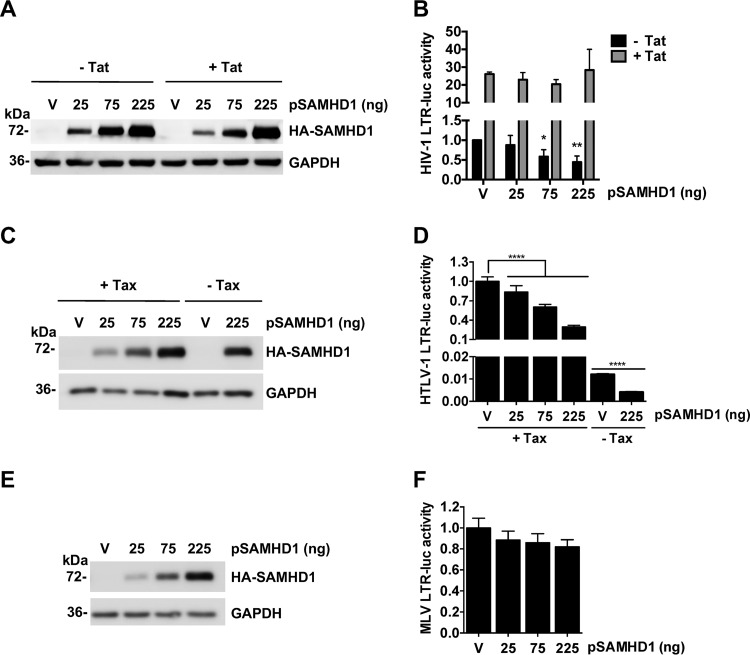

SAMHD1 suppresses gene expression driven by the LTR from HIV-1 and HTLV-1 but not from MLV.

To examine the specificity of SAMHD1-mediated suppression of LTR-driven gene expression, we tested luciferase reporters driven by LTR promoters derived from the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) or murine leukemia virus (MLV) LTR in addition to the HIV-1 LTR FF-Luc reporter. The TK promoter-driven Ren-Luc reporter was used as a transfection control. Since HIV-1 and HTLV-1 utilize viral proteins Tat (44) and Tax (45), respectively, to enhance viral transcription via transactivation, we compared the abilities of SAMHD1 to suppress HIV-1 and HTLV-1 LTR-driven gene expression with or without transactivation. Increased levels of exogenous SAMHD1 expression in transfected HEK293T cells were confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A, C, and E). Although SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression in the absence of Tat (Fig. 2B, filled bars), Tat expression led to a 20- to 28-fold enhancement of HIV-1 LTR activity that was not suppressed by SAMHD1 (Fig. 2B, shaded bars). Conversely, HTLV-1 LTR activity was potently suppressed by SAMHD1 expression, with a ≤75% reduction in luciferase activity at the highest level of SAMHD1 expression in the presence or absence of Tax (Fig. 2D). SAMHD1 expression had no effect on MLV LTR activity (Fig. 2F). These data suggest that SAMHD1 selectively suppresses retroviral LTR-driven gene expression.

FIG 2.

SAMHD1 suppresses gene expression driven by the LTR from HIV-1 or HTLV-1 but not from MLV. (A to F) HEK293T cells were transfected with an empty vector (V) or increasing amounts of constructs expressing HA-tagged SAMHD1 and either an HIV-1 LTR-driven FF-Luc construct with (+) or without (−) an HIV-1 Tat-expressing plasmid (A and B), an HTLV-1 LTR-driven FF-Luc construct with or without an HTLV-1 Tax-encoding plasmid (C and D), or an MLV LTR-driven FF-Luc construct (E and F). Overexpression of SAMHD1 was analyzed by immunoblotting (A, C, and E) with GAPDH as a loading control. Cotransfection of Ren-Luc was used as a control of transfection efficiency, with LTR-driven FF-Luc activity normalized to Ren-Luc activity. (B, D, and F) Luciferase activity was determined 24 h posttransfection. Error bars show standard errors of the means for three (HIV-Luc with or without Tat, HTLV-Luc with Tax) or two (HTLV-Luc without Tax, MLV-Luc) independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison posttest. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001) from results for vector (V) control cells.

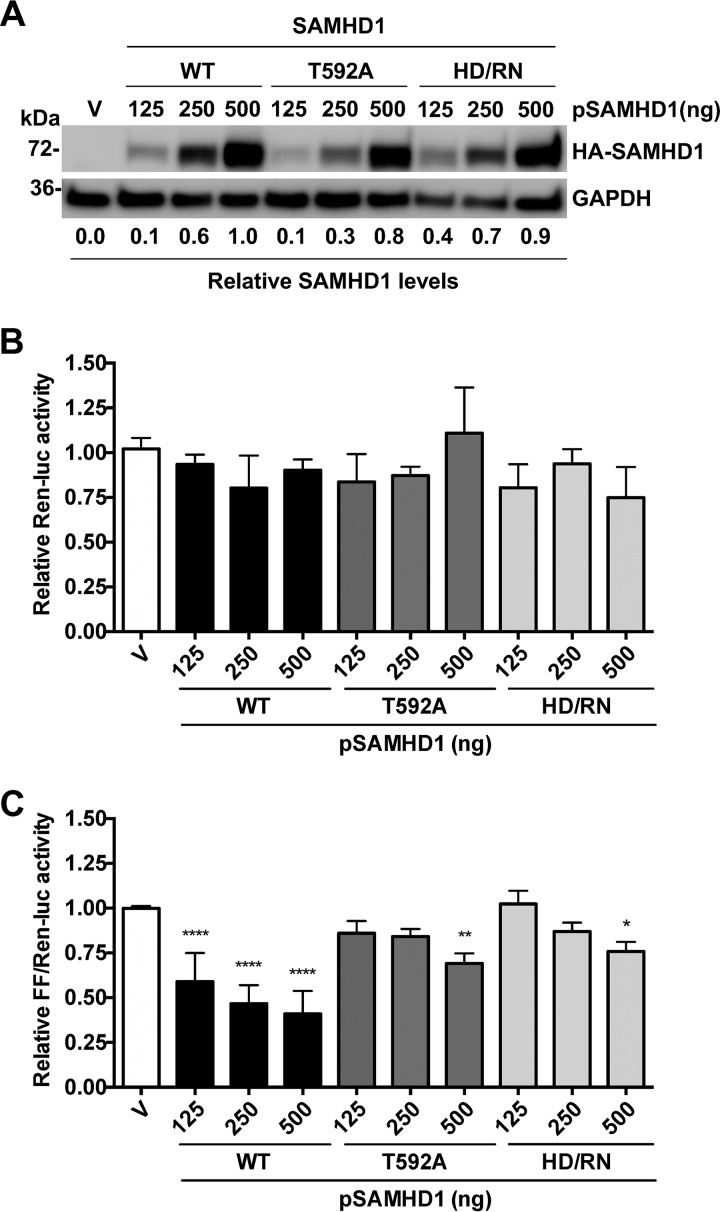

Nonphosphorylated and dNTPase-inactive SAMHD1 mutants have impaired suppression of HIV-1 LTR activity.

SAMHD1 is predominantly phosphorylated in HEK293T cells (25, 27). To assess the effects of dNTPase activity and T592 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 on the suppression of LTR-driven gene expression, we tested a catalytically inactive SAMHD1 mutant (H206D R207N [HD/RN]) (30) and a nonphosphorylated T592A mutant (26). HEK293T cells were transfected with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding wild-type (WT), T592A, or HD/RN mutant SAMHD1, along with the HIV-1 LTR-driven FF-Luc reporter. Comparable WT and mutant SAMHD1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). Undetectable phosphorylation of the T592A mutant was confirmed in our previous studies (21). The TK promoter-driven Ren-Luc reporter showed similar activities across all samples (Fig. 3B), confirming comparable transfection efficiencies. Relative to the vector control (and normalized to Ren-Luc activity), WT SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 LTR-driven FF-Luc expression as much as 60% in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). In contrast to WT SAMHD1, small amounts of the HD/RN or T592A mutant (plasmid input, 125 or 250 ng) did not significantly inhibit HIV-1 LTR activity. However, modest inhibition of LTR-driven FF-Luc activity (between 25 and 31%) was observed at the highest levels of mutant SAMHD1 expression (plasmid input, 500 ng) (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that the T592A and HD/RN mutants have a diminished ability to suppress HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression relative to that of WT SAMHD1, suggesting that the suppression of HIV-1 gene expression mediated by SAMHD1 is partially dependent on its dNTPase activity and T592 phosphorylation.

FIG 3.

Nonphosphorylated and dNTPase-inactive SAMHD1 mutants show impaired suppression of HIV-1 LTR activity. (A to C) An HIV-1 LTR-driven FF-Luc construct was cotransfected with increasing amounts of plasmids encoding HA-tagged WT SAMHD1, the nonphosphorylated T592A mutant, or the dNTPase-inactive HD/RN mutant into HEK293T cells. Cotransfection of Ren-Luc was used as a control of transfection efficiency. (A) SAMHD1 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Relative SAMHD1 expression levels quantified by densitometry were normalized to GAPDH levels. (B and C) Relative Ren-Luc units were normalized to the total protein concentration (B), and relative FF-Luc units were normalized to Ren-Luc levels (C). Vector cell luciferase activity was set as 1. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison posttest. Error bars show standard deviations from at least three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ****, P ≤ 0.0001) from results for vector control cells.

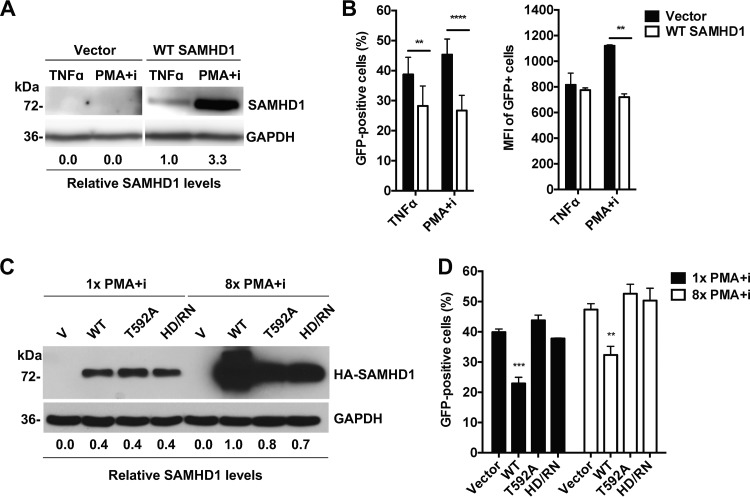

WT SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected J-Lat cells.

To investigate whether SAMHD1 suppresses HIV-1 gene expression in CD4+ T cells, we used Jurkat CD4+ T-cell-line-derived J-Lat cells (46). J-Lat cells have been used as an HIV-1 latency model, since they contain a full-length HIV-1 provirus with a green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene inserted in the nef region (46). Treatment of J-Lat cells with latency-reversing agents (LRAs) results in activation of LTR-driven gene expression, indicated by an increase in GFP expression (46, 47). Since J-Lat cells do not express detectable endogenous SAMHD1 protein, likely due to gene promoter methylation as reported in Jurkat cells (48), we stably expressed WT SAMHD1 in J-Lat cells by lentiviral transduction. Empty-vector-transduced cells were used as a control. Previous studies showed that efficient SAMHD1 expression driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early promoter of stably integrated lentiviral vectors in monocytic cell lines is dependent on treatment of cells with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (4, 27), which is a protein C kinase agonist that activates the NF-κB signaling pathway (49, 50).

To activate HIV-1 gene expression in J-Lat cells, we applied two LRAs: tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which induces HIV-1 gene expression by activating the NF-κB pathway (47, 51, 52), and PMA in conjunction with ionomycin (PMA+i), which has been shown to be the strongest activator of HIV-1 gene expression in several J-Lat cell clones (47). Treatment of J-Lat cells with TNF-α (Fig. 4A) resulted in GFP expression in 38% of vector control cells (Fig. 4B), a result consistent with published data (46, 47). In contrast, expression of WT SAMHD1 reduced TNF-α-induced GFP expression to 27% (Fig. 4B), suggesting that SAMHD1 impairs TNF-α-induced HIV-1 reactivation. Treatment of WT SAMHD1-expressing J-Lat cells with PMA+i resulted in a significant increase in SAMHD1 expression (Fig. 4A) and a significant decrease in GFP expression, by 20%, from that in vector control cells (Fig. 4B). While PMA+i treatment resulted in 1.5-fold-lower GFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in SAMHD1-expressing cells than in vector control cells, the MFI of TNF-α-treated cells was not significantly reduced by SAMHD1 expression (Fig. 4B).

FIG 4.

WT SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected J-Lat cells. (A and C) HA-tagged WT SAMHD1, SAMHD1 mutants, or an empty vector (V) was stably expressed in J-Lat cells by lentiviral transduction. Relative SAMHD1 expression levels quantified by densitometry were normalized to GAPDH levels. (A and B) The cells were treated with either 10 ng/ml TNF-α or 32 nM PMA with 1 μM ionomycin (PMA+i). (A) At 24 h posttreatment, the expression of SAMHD1 was detected by immunoblotting, quantified by densitometry, and normalized to GAPDH levels. (B) The percentage of GFP-positive cells and the relative GFP mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) were determined by flow cytometry. (C) J-Lat cells expressing the T592A or HD/RN mutant were treated with 1× or 8× PMA+i (1× PMA+i corresponds to 16 nM PMA and 0.5 μM ionomycin), with expression of SAMHD1 measured and quantified by immunoblotting. (D) Latency reversal, as measured by the percentage of the cell population that was GFP positive and the MFI of GFP-positive cells, was determined by flow cytometry. Error bars in panels B and D represent standard deviations from at least three independent experiments analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (**, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001) from results for vector cells in panels B and D.

To examine whether increased SAMHD1 expression in J-Lat cells could more efficiently suppress HIV-1 reactivation, we compared J-Lat cells treated with two PMA+i concentrations with a 8-fold difference (Fig. 4C and D). To examine whether the dNTPase activity or T592 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 affects its suppression of HIV-1 reactivation in J-Lat cells, we performed the analysis in J-Lat cells stably expressing WT SAMHD1, the T592A mutant, or the HD/RN mutant by lentiviral transduction. Similar expression levels of WT SAMHD1 and the mutants were observed in 1× PMA+i-treated cells, while 8× PMA+i treatment increased the expression levels of WT SAMHD1 dramatically and those of mutant SAMHD1 to a lesser degree (Fig. 4C). WT SAMHD1-expressing cells had a 15% lower GFP-positive cell population than vector control cells at 1× PMA+i; however, this effect was not further enhanced by increased WT SAMHD1 expression at 8× PMA+i (Fig. 4D). While WT SAMHD1 suppressed HIV-1 reactivation with both 1× and 8× PMA+i treatment, neither the T592A nor the HD/RN mutant had a suppression effect (Fig. 4D), suggesting that T592 phosphorylation and the dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 likely contribute to the inhibition of HIV-1 latency.

WT SAMHD1 binds to the HIV-1 LTR of proviral DNA in J-Lat cells.

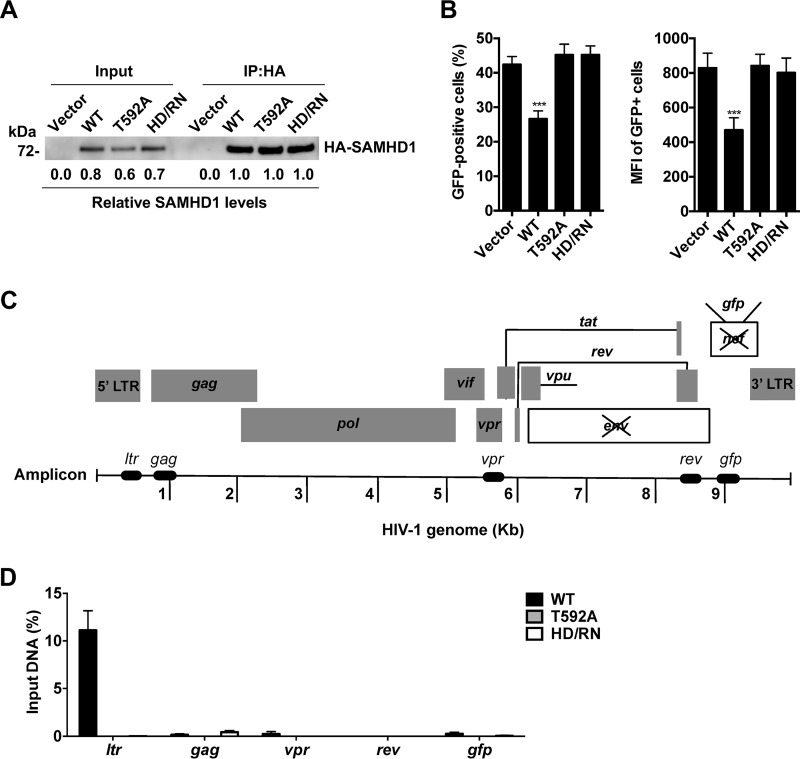

One common mechanism by which host proteins modulate HIV-1 LTR activity is transcriptional repression through direct binding to the promoter (53). SAMHD1 is a DNA binding protein (20) capable of interacting with in vitro-transcribed HIV-1 gag DNA fragments (15). However, interaction between SAMHD1 and integrated HIV-1 proviral DNA in cells has not been reported. To address this question, we performed a ChIP-qPCR (chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with quantitative real-time PCR) experiment in J-Lat cells expressing WT, T592A, or HD/RN SAMHD1. To induce high levels of SAMHD1 for efficient immunoprecipitation (IP), we treated the cells with increased PMA+i concentrations. Treatment with 8× PMA+i allowed for maximum SAMHD1 expression without cell death (data not shown). However, WT SAMHD1 was expressed at levels 20 to 30% higher than those of mutants under this condition (Fig. 4C). We treated WT SAMHD1-expressing cells with 50% less PMA+i than was used for mutant-expressing cells and obtained comparable levels of SAMHD1 (Fig. 5A). HIV-1 reactivation in all cell lines was measured by GFP expression (Fig. 5B). WT SAMHD1-expressing J-Lat cells had a 17% lower GFP-positive population than cells expressing the vector control, T592A mutant, or HD/RN mutant, which was reflected in a 1.6-fold-lower MFI (Fig. 5B). After IP of WT or mutant SAMHD1 from cells treated with PMA+i (Fig. 5A), total bound DNA was eluted and quantified by qPCR. We used PCR primers specific for different regions in the HIV-1 genome, including the LTR and the gag, vpr, and rev genes, to characterize the regions of interaction between SAMHD1 and proviral DNA (Fig. 5C; Table 1). We also included gfp-specific PCR primers as an additional control, since gfp is a nonviral gene inserted into the nef gene of HIV-1 in J-Lat cells (46). We observed that only DNA fragments derived from the LTR (12% of input) bound to WT SAMHD1 (Fig. 5D). WT SAMHD1 did not bind other HIV-1 genes tested or the gfp gene. These data suggest that the SAMHD1–DNA interaction occurs in the LTR promoter region of the HIV-1 provirus. Interestingly, analysis of the DNA eluted from IP products of T592A and HD/RN SAMHD1 revealed that neither mutant bound to tested HIV-1 DNA sequences or gfp cDNA (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data indicate that mutant SAMHD1 cannot suppress latency reactivation or bind to proviral DNA, suggesting that direct binding to the HIV-1 LTR is partially responsible for the mechanism of SAMHD1-mediated suppression of LTR-driven gene expression.

FIG 5.

WT SAMHD1 binds to HIV-1 proviral DNA in latently infected J-Lat cells. (A to D) J-Lat cells were seeded in the presence of PMA+i for 24 h. To achieve similar SAMHD1 expression levels, WT SAMHD1-expressing cells were treated with 4× PMA+i, while vector control cells and cells expressing T592A or HD/RN SAMHD1 were treated with 8× PMA+i. (A) SAMHD1 expression in input and IP lysates was analyzed by immunoblotting and densitometry. (B) Latency reversal, as measured by the percentage of the cell population that was GFP positive and the MFI of GFP-positive cells, was determined by flow cytometry. Three independent experiments were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple-comparison test. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means. Asterisks indicate significant differences (***, P ≤ 0.001) from results for vector control cells. (C) Diagram of the locations of the qPCR amplicons. (D) Quantitative PCR data were normalized to spliced GAPDH levels and are presented as percentages of input in SAMHD1-expressing cells after normalization to vector background levels. Error bars represent the standard errors of the means from two independent experiments.

TABLE 1.

PCR primer sequences

| PCR primera | DNA sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| ltr F | CGAACAGGGACTTGAAAGC |

| ltr R | CATCTCTCTCCTTCTAGCCTC |

| gag F | CTAGAACGATTCGCAGTTAATCCT |

| gag R | CTATCCTTTGATGCACACAATAGAG |

| vpr F | GCCGCTCTAGAACCATGGAACAAGCCCCAGAAGACCAA |

| vpr R | GCCGCCGGTACCGGATCTACTGGCTCCATTTCTTGCT |

| rev F | CGGCGACTGCCTTAGGCATC |

| rev R | CTCGGGATTGGGAGGTGGGTC |

| gapdh F | GATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCATG |

| gapdh R | TGGATATTGCCATCAATGACC |

| gfp F | ACGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTC |

| gfp R | AAGTCGTGCTGCTTCATGTG |

| Ren-luc F | GAGCATCAAGATAAGATCAAAGCA |

| Ren-luc R | CTTCACCTTTCTCTTTGAATGGTT |

| FF-luc F | GGTTGGCAGAAGCTATGAAAC |

| FF-luc R | CATTATAAATGTCGTTCGCGGG |

F, forward; R, reverse; Ren-luc, Renilla luciferase; FF-luc, firefly luciferase.

Purified recombinant WT SAMHD1 binds to HIV-1 LTR fragments in vitro.

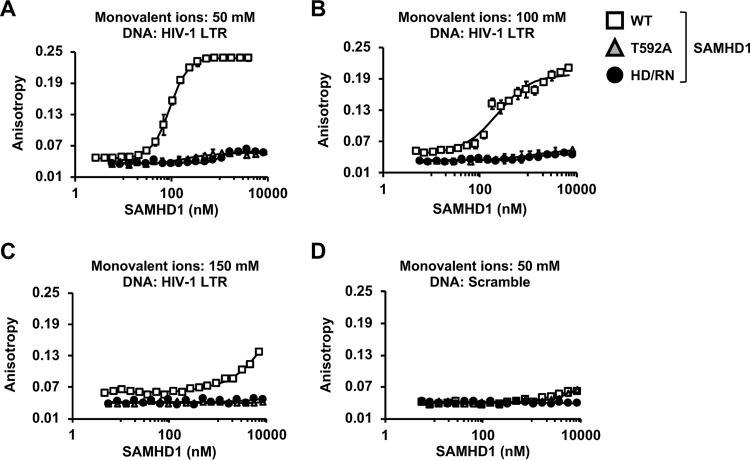

To investigate the underlying mechanism of SAMHD1-mediated suppression of HIV-1 LTR activity and viral reactivation in cells, we determined whether this suppression effect correlated with SAMHD1 binding to the HIV-1 LTR in vitro. Fluorescence anisotropy (FA) (54) was used to measure the binding of WT SAMHD1, the T592A mutant, or the HD/RN mutant to a 90-mer 5′-6-carboxyfluorescein (6-FAM)-labeled DNA oligonucleotide derived from the HIV-1 LTR (Table 2). Binding was measured over a range of SAMHD1 concentrations and three monovalent ion concentrations (50, 100, and 150 mM) to determine whether the interaction is mediated by electrostatic interactions. While WT SAMHD1 binding to the HIV-1 LTR fragment was detected at all three salt concentrations tested, higher salt concentrations reduced the level of binding observed (Fig. 6A to C), suggesting that the interaction is mediated, at least in part, by electrostatic contacts. In contrast, no significant binding was observed for the T592A and HD/RN mutants even at the highest protein concentration (8,300 nM) (Fig. 6A to C). For WT SAMHD1, saturated or near-saturated binding was observed at 50 and 100 mM monovalent ions (Fig. 6A and B), with calculated apparent Kd (dissociation constant) values of 93 ± 8 and 242 ± 51 nM, respectively. Importantly, none of the SAMHD1 proteins bound to a 90-mer 6-FAM-labeled DNA oligonucleotide derived from a scrambled sequence of the HIV-1 LTR (Table 2), even at a low (50 mM) monovalent ion concentration (Fig. 6D). These data indicate that WT SAMHD1 binds specifically to HIV-1 LTR-derived fragments in a salt-sensitive manner.

TABLE 2.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in anisotropy binding assays

| Oligonucleotide (90-mer) | DNA sequence (5′–3′), 5′ 6-FAM labeled |

|---|---|

| HIV-1 LTR | AGCAGTGGCGCCCGAACAGGGACTTGAAAGCGAAAGTAAAGCCAGAGGAGATCTCTCGACGCAGGACTCGGCTTGCTGAAGCGCGCACGG |

| Scrambled DNA | ACTAGCTCAAGCGGGGGACACCCAGGTGTCTCCAACAGTCCGTAGATCGGACGGAGAAGAGGGGACCCCGCTAATGAGCGTGAGCAGAGA |

FIG 6.

Specific binding of WT SAMHD1 to an HIV-1 LTR fragment in vitro. (A to C) Results of FA binding assays for WT, T592A mutant, or HD/RN mutant SAMHD1 binding to a 90-mer fragment of the HIV-1 LTR in 50 mM, 100 mM, or 150 mM monovalent ions (25, 50, or 75 mM [each] NaCl and KCl), respectively. (D) Binding to a 90-mer scrambled DNA oligonucleotide was also tested at 50 mM monovalent ions (25 mM [each] NaCl and KCl). Error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent experiments.

SAMHD1 knockdown promotes HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected primary CD4+ T cells.

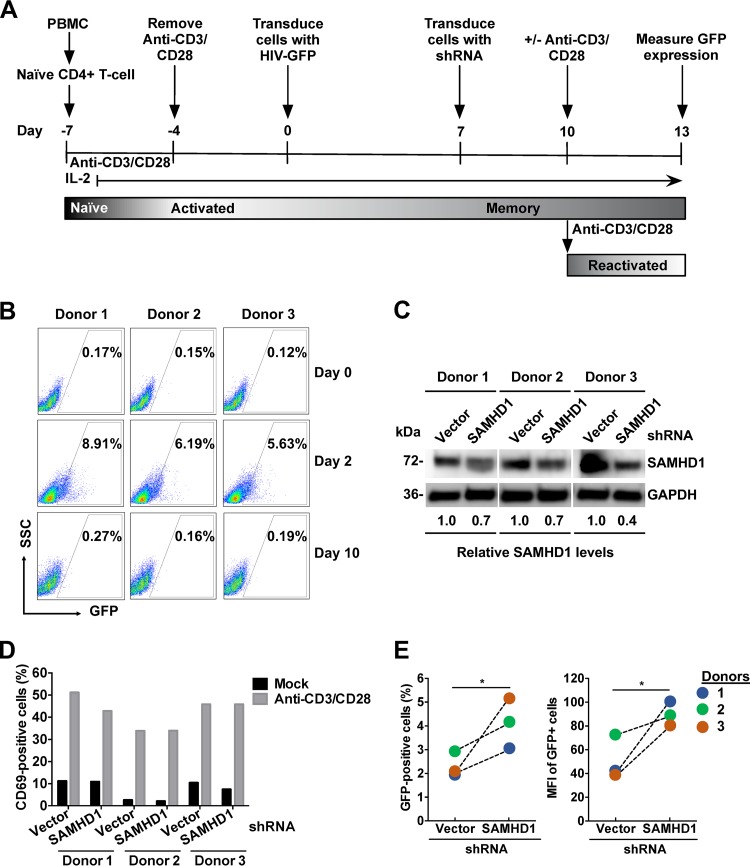

To examine the effect of endogenous SAMHD1 on HIV-1 reactivation in primary CD4+ T cells, we utilized the established central memory T-cell (TCM) model of HIV-1 latency (40, 55) as depicted in the protocol in Fig. 7A. We measured GFP expression at days 2 and 10 after transduction with a GFP reporter HIV-1 vector to confirm productive infection and transition into latency, respectively (Fig. 7B). Baseline GFP expression measured at day 0 (0.12 to 0.17%) before the transduction served as a negative control (Fig. 7B). As expected, at 2 days postransduction, 5.6 to 8.9% of TCMs from three donors were positive for GFP expression, indicating productive infection. At day 10 posttransduction, TCMs from all three donors had baseline GFP expression (Fig. 7B), confirming that the cells had become latently infected (40, 55).

FIG 7.

Endogenous SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected primary CD4+ T cells. (A) Protocol summary. Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs from three different healthy donors, activated by incubation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody-coated beads, and infected with a single-cycle HIV-1 containing a GFP reporter pseudotyped with VSV-G (HIV-GFP) to produce a primary TCM model of latency. (B) GFP expression was measured in TCMs before HIV-GFP infection (day 0), as well as 2 and 10 days postinfection, by flow cytometry. SSC, side scatter. (C) After infection and culture to produce latently infected quiescent CD4+ T cells, the cells were transduced either with an empty vector or with lentiviral vectors containing SAMHD1-specific shRNA to knock down SAMHD1 expression. Endogenous SAMHD1 protein expression was measured at day 13 by immunoblotting, and GAPDH served as a loading control. (D and E) After stimulation of the cells with anti-CD3/CD28, T-cell activation was measured by surface staining of CD69 (D), and HIV-1 reactivation was measured by GFP expression by flow cytometry (E), at day 13. (E) Changes in the percentages and the MFI of GFP-positive cells from three donors are shown. *, P ≤ 0.05.

Using a SAMHD1-specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA) and an established method (56, 57), we knocked down 30 to 60% of endogenous SAMHD1 expression in latently infected TCMs derived from naïve CD4+ T cells isolated from three healthy donors (Fig. 7C). Next, we reactivated latently infected GFP reporter HIV-1 in TCMs by CD3/CD28 antibody treatment. To confirm CD4+ T-cell activation, we measured the T-cell activation marker CD69 by cell-surface staining and flow cytometry (58). Three days postreactivation, 35 to 50% of CD3/CD28 antibody-treated TCMs expressed CD69, in contrast to 3 to 10% of mock-treated cells (Fig. 7D). We measured GFP expression in TCMs as a readout of HIV-1 latency reactivation. As a negative control, TCMs treated with medium did not express GFP. Upon activation of latently infected TCMs, partial knockdown of SAMHD1 enhanced HIV-1 reactivation 1.5- to 2.5-fold across the three donors, with an average of 1.7-fold, over reactivation in cells transduced with an empty shRNA vector, as measured by the percentage and MFI of GFP-positive cells (Fig. 7E). These results suggest that endogenous SAMHD1 is a negative regulator of HIV-1 reactivation in latently infected primary CD4+ T cells.

DISCUSSION

One of the hallmarks of HIV-1 persistence is the maintenance of a long-lived stable proviral reservoir that is formed after infection in resting CD4+ T cells (32, 59). Although the integrated provirus is transcriptionally silent, it is capable of full reactivation and production of infectious virus upon discontinuation of therapy or upon treatment with LRAs (32, 41, 59). In this study, we tested the hypothesis that SAMHD1 plays a role in negatively regulating HIV-1 reactivation and viral latency by suppressing HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression.

We demonstrated that WT SAMHD1 suppresses HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression, in the absence of Tat, in HEK293T and THP-1 cells. Previous work confirmed that SAMHD1 does not degrade HIV-1 genomic RNA or mRNA (20, 21), thereby excluding the possibility that mRNA degradation causes the suppression. We observed that SAMHD1 potently suppressed the HTLV-1 LTR independently of Tax expression but had no effect on the MLV LTR, or on the HIV-1 LTR in the presence of Tat. These differences in suppression could be the result of variations in the transcriptional control of each LTR. Tat transactivation of the HIV-1 LTR occurs through direct binding of Tat to the HIV-1 transactivation-responsive region (TAR) (44, 60). Tat-TAR binding affinity is particularly tight, with a Kd of 1 to 3 nM (44, 61), making effective competition by SAMHD1 very unlikely. In our overexpression system, Tat transactivation may saturate LTR activity and mask a SAMHD1-mediated suppressive effect. Moreover, we previously observed that SAMHD1 expression does not affect HIV-1 Gag expression from transfected HIV-1 proviral DNA when Tat is present (21). Conversely, Tax transactivation occurs through the mediation of interactions with host factors, specifically the CREB/CBP/p300 complex (45, 62, 63). Whether SAMHD1 interacts with host proteins to further suppress HTLV-1 LTR activity through disruption of Tax activity is unknown. As a simple retrovirus, MLV does not encode transactivation accessory proteins; however, its LTR has several binding sites for transcription factors, including nuclear factor 1 (64). Our data suggest that SAMHD1-mediated suppression of LTR activity may be specific for complex human retroviruses and could be influenced by certain transcription factors that bind to each respective LTR.

SAMHD1 enzyme activity can be regulated by mutations to its catalytic core or by posttranslational modifications (65). Thus, we used two SAMHD1 mutants to determine the contributions of phosphorylation and dNTPase activity to the suppression of LTR-driven gene expression. Both the nonphosphorylated T592A mutant and the dNTPase-inactive HD/RN mutant had reduced ability to suppress HIV-1 LTR-driven gene expression. It is unlikely that a reduction in dNTP levels is required for the effect on LTR-driven gene expression, since dNTP levels are high in HEK293T cells despite SAMHD1 overexpression (66). Interestingly, whereas WT SAMHD1 was observed to bind specifically to the HIV-1 LTR in both ChIP-qPCR and in vitro binding experiments, the SAMHD1 mutants failed to bind to the HIV-1 DNA regions tested. It is possible that SAMHD1 oligomerization plays a role in the ability of SAMHD1 to bind DNA. Dimeric SAMHD1 binds ssNA; however, previous reports have shown that tetramerization of SAMHD1 inhibits NA binding (18, 20).

Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 at residue T592 destabilizes tetramer formation and impairs the dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 (67, 68); the binding of phosphomimetic T592E SAMHD1 to ssRNA and ssDNA is identical to that of WT SAMHD1 (20). In vitro, the HD/RN mutant tetramerizes to a greater extent than WT SAMHD1 (69), and mutations of either the H206 or the D207 residue result in loss of ssDNA binding (15). It is possible that the T592A and HD/RN mutants form more-stable tetramers and, as a consequence, lose the ability to bind the LTR and suppress activation. Experiments to determine the oligomeric states of WT, T592A, and HD/RN SAMHD1 in the presence of fragments of the HIV-1 LTR can help to further test this possibility. Further studies are required to map the region of interaction between SAMHD1 and the HIV-1 LTR and to examine the contribution of binding to the suppression of LTR-driven gene expression. Taken together, our data suggest a mechanism for suppression of LTR activity in which WT SAMHD1 is able to bind directly to the LTR and possibly to occlude transcription factors required for LTR activity. Our recent work identified SAMHD1 as a negative regulator of the innate immune response to inflammatory stimuli and viral infections through inhibition of the NF-κB and interferon pathways (57). Since LTR activity is potently enhanced through its direct binding of NF-κB (52), downregulation of the NF-κB pathway could lead to suppression of LTR activity. Further work is necessary to determine whether direct binding to the LTR and suppression of the NF-κB pathway by SAMHD1 collaboratively contribute to SAMHD1-mediated downregulation of LTR activity.

Since suppression of the HIV-1 LTR is a common mechanism contributing to latency (53), we aimed to determine whether SAMHD1 affects latency reversal in cells. We utilized two HIV-1 latency cell models, the J-Lat cell line and primary TCMs (40, 46, 55, 56). In both models, SAMHD1 expression resulted in a suppression of latency reactivation. The modest effect observed could be due to saturation of the NF-κB pathway caused by PMA and TNF-α in J-Lat cells (Fig. 4) or anti-CD3/CD28 (Fig. 7) in TCMs, since significant activation of the LTR may mask the suppressive effect of SAMHD1 (47, 51, 70, 71). Additionally, since Tat expression diminishes the SAMHD1-mediated suppression of LTR-driven gene expression (Fig. 2B), Tat expression in reactivated J-Lat cells or primary TCMs may also account for the modest suppression of latency reversal (Fig. 4 and 7). Finally, the modest suppression of latency reactivation in primary CD4+ T cells may be due to partial knockdown of endogenous SAMHD1.

In summary, our data indicate a correlation between SAMHD1 binding to the HIV-1 LTR and SAMHD1-mediated suppression of viral gene expression and reactivation of HIV-1 latency, suggesting that SAMHD1 is among the host proteins involved in the transcriptional regulation of proviral DNA. Our results further suggest that the T592 and H206–D207 residues of SAMHD1 are important for LTR binding and the suppression of HIV-1 gene expression. Future studies using latently infected cells from HIV-1 patients and primary HIV-1 isolates will further inform our understanding of the function and mechanisms of SAMHD1 as a novel modulator of HIV-1 latency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained as described previously (27). Jurkat cell-derived J-Lat cells (clone 9.2) were obtained from the NIH AIDS reagent program and maintained as described previously (46). THP-1 control cells and derived SAMHD1 KO cells were maintained as described previously (29). All cell lines tested negative for mycoplasma contamination by use of a PCR-based universal mycoplasma detection kit (ATCC 30-1012K). Healthy human donors' peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the buffy coat as described previously (72). Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated from PBMCs by MACS MicroBeads with negative selection and the naïve CD4+ T-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Primary CD4+ T cells were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium in the presence of 30 IU/ml of recombinant interleukin 2 (rIL-2) (obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program [catalog no. 136]) (27).

Plasmids.

The pLenti-puro vectors encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged WT SAMHD1 (driven by the CMV immediate-early promoter) and the empty vector have been described elsewhere (4) and were provided by Nathaniel Landau (New York University). The pLenti-puro vector expressing the HA-tagged T592A and HD/RN SAMHD1 mutant constructs were generated using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies) (27). The HTLV-1 LTR luciferase reporter plasmid and pcTax were provided by Patrick Green (The Ohio State University) (73). The HIV-1 FF-Luc vector (pGL3-LTR-luc) was provided by Jian-Hua Wang (Pasteur Institute of Shanghai) (56). The TK promoter-driven Ren-Luc reporter plasmid (pRenilla-TK) was provided by Kathleen Boris-Lawrie (University of Minnesota). The pTat plasmid is a pcDNA3-based HIV-1 Tat expression construct (74) provided by Vineet KewalRamani (National Cancer Institute). The MLV LTR reporter (pFB-Luc), containing the MLV 5′ LTR, truncated gag, 3′ LTR, and firefly luciferase gene, was provided by Vineet KewalRamani (National Cancer Institute).

Transfection assays.

HEK293T cells (5.0 × 104 cells in the experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 1; 1.0 × 105 cells in the experiments for which results are shown in Fig. 2 and 3) were cotransfected with a viral LTR-driven luciferase construct (HIV-1, HTLV-1, or MLV), pRenilla-TK, and increasing amounts of a WT, T592A, or HD/RN SAMHD1-expressing plasmid using calcium phosphate as described previously (27). The total amount of DNA transfected was maintained through addition of an empty vector. The transfection medium was replaced with fresh medium at 16 h after transfection. Nucleofection of control and SAMHD1 KO THP-1 cells with the HIV-1-LTR-Luc reporter and pRenilla-TK was performed using Amaxa Cell Line Nucleofector kit V (Lonza).

Immunoblotting and antibodies.

Cells were harvested 24 h after transfection or as specifically indicated in the legends, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed with cell lysis buffer (catalog no. 9803; Cell Signaling Technology) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. P8340; Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates were prepared for immunoblotting as described previously (27). HA-tagged SAMHD1 and endogenous glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were detected using an antibody specific to HA (Ha.11 clone 16B12; Covance) at a 1:1,000 dilution and an antibody specific to GAPDH (catalog no. AHP1628; Bio-Rad) at a 1:3,000 dilution. A polyclonal SAMHD1-specific antibody (catalog no. ab67820; Abcam) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution for immunoblotting, as described previously (66). Immunoblots were imaged and analyzed using the Amersham imager 600 (GE Healthcare). Validation for all antibodies is provided on the manufacturers' websites.

Densitometry quantification of immunoblots.

Densitometry analysis was performed on unaltered low-exposure images using ImageJ software. Densitometry values were normalized to GAPDH levels.

Protein expression and purification.

Full-length cDNAs of WT, T592A, and HD/RN SAMHD1 were cloned into a pET28a expression vector with a 6×His tag at the N terminus and were expressed in Escherichia coli. SAMHD1 proteins were purified using a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column as described previously (75). The eluted peak fractions were collected, dialyzed into the assay buffer, and further purified by size exclusion chromatography as described previously (21). SAMHD1 protein was stored in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine at −80°C.

Synthetic DNA oligonucleotides.

The oligonucleotides used in FA binding assays, and those used as primers for qPCR, were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. The sequences of oligonucleotides and primers are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A 90-mer 6-FAM-labeled DNA oligonucleotide derived from the scrambled sequence of the HIV-1 LTR was obtained using the Sequence Manipulation Suite (Bioinformatics.org).

FA binding assays.

FA binding assays were performed as described previously (54, 76) using the 5′-6-FAM-labeled DNA sequences shown in Table 2. Briefly, proteins were incubated with 10 nM DNA at room temperature for 30 min in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM HEPES, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 50, 100, or 150 mM monovalent ions (25, 50, or 75 mM [each] NaCl and KCl). Each measurement was performed in triplicate over a range of WT or mutant SAMHD1 concentrations (5 to 8,300 nM). Binding affinities were calculated by fitting the data to a 1:1 binding model, as described previously (77). Fluorescence measurements were obtained using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Generation of SAMHD1-expressing J-Lat cell lines.

HEK293T cells were transfected with the pLenti-puro vector or an HA-tagged SAMHD1 (WT, T592A mutant, or HD/RN mutant)-expressing plasmid, the pMDL packaging construct, the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein-expressing construct pVSV-G, and pRSV-Rev to produce lentiviral stocks for spinoculation at 2,000 × g for 2 h at room temperature. Lentiviral stocks were harvested, filtered, and concentrated through a sucrose cushion at 48 h posttransfection. The concentrated lentivirus stock was resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium and applied to J-Lat cells (clone 9.2) with Polybrene (8 μg/ml) prior to spinoculation. Afterwards, cells were cultured in complete RPMI medium for 72 h before undergoing selection with 0.8 μg/ml puromycin.

HIV-1 reactivation assay in J-Lat cells.

J-Lat cells (clone 9.2) stably expressing WT, T592A, or HD/RN SAMHD1 were generated as described above. Cells were treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α or 32 nM PMA with 1 μM ionomycin (2× PMA+i) unless otherwise described in the figure legends. At 24 h posttreatment, the medium was removed, and cells were washed and placed in untreated complete RPMI 1640 medium for an additional 12 h. Cells were collected, washed twice with 1× PBS, and suspended in 2% fetal bovine serum in PBS. Cells were evaluated by flow cytometry using a Guava EasyCyte Mini flow cytometer (Millipore), with data analyzed by FlowJo software.

IP of SAMHD1 in J-Lat cells.

J-Lat cells (clone 9.2) expressing WT or mutant SAMHD1 and the vector control cells were differentiated using either 64 nM PMA (for WT SAMHD1) or 128 nM PMA (for the vector, the T592A mutant, and the HD/RN mutant) for 24 h. At 36 h posttreatment, cells were treated with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min before the reaction was quenched with 0.125 M glycine. Cells were lysed in non-SDS-containing radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer and were sonicated to shear cellular chromatin. Monoclonal anti-HA-agarose beads were incubated with 250 μg of lysates from cells expressing WT, T592A, or HD/RN SAMHD1 or from vector control cells at 4°C for 2 h. Beads were washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween. To confirm IP efficiency, bound proteins were eluted from beads by boiling in 1× SDS-sample buffer, and the supernatants were analyzed by immunoblotting as described previously (27). Total DNA was isolated from proteinase K-treated, sonicated input lysates and IP products using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen).

qPCR assay.

For quantification of Renilla or firefly luciferase mRNA in transfected HEK293T cells, total cellular RNA was extracted using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Equal amounts of total RNA from each sample were used as a template for first-strand cDNA synthesis using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system and oligo(dT) primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). SYBR green-based PCR analysis was performed using the specific primers detailed in Table 1 and methods described previously (66). Quantification of spliced GAPDH mRNA was used for normalization as described previously (66). Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method as described previously (78).

The levels of SAMHD1-bound HIV-1 genomic DNA from PMA-treated latently infected J-Lat cells were measured by SYBR-green-based qPCR using the primers detailed in Table 1 and methods described previously (66, 79). DNA samples without primer templates were used as negative controls. Genomic DNA (50 ng) from PMA-treated SAMHD1-expressing or vector control J-Lat cells after IP was used as input for the detection of HIV-1 genes. Data were normalized to vector background levels and are presented as percentages of total input DNA.

Generation of SAMHD1-specific and control shRNA vectors.

HEK293T cells were transfected with the empty vector pLKO.1-puro (GE Dharmacon) and SAMHD1-specific shRNA-expressing plasmids (clone TRCN0000145408; GE Dharmacon), a psPAX2 packaging construct, and pVSV-G to produce lentiviral stocks (57) for spinoculation at 2,000 × g for 2 h at room temperature. Lentiviral stocks were harvested, filtered, and concentrated through a sucrose cushion at 48 h posttransfection. Concentrated lentivirus stocks were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium and applied to isolated naïve CD4+ T cells with Polybrene (8 μg/ml) prior to spinoculation. Afterwards, cells were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium with 30 IU/ml of IL-2.

HIV-1 latency reactivation assay in primary TCMs.

We utilized the primary TCM model of latency as described previously (55, 56). In brief, naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated for 72 h with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody-coated magnetic beads (Dynabeads). After an additional 4 days of culture, cells were infected with VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1-GFP and were cultured for 7 days to produce latently infected TCMs (40). GFP expression was measured by flow cytometry at day 0 (before transduction with HIV-GFP) and at days 2 and 10 postransduction. Next, cells were transduced with lentiviral vectors containing vector control or SAMHD1 shRNA for 3 days before activation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibody-coated magnetic beads for an additional 3 days (mock treatment without the anti-CD3/CD28 antibody was used as the negative control). At day 13, SAMHD1 expression was detected by immunoblotting, and T-cell activation was measured in mock- and anti-CD3/CD28-treated cells by surface staining with anti-CD69 (clone FN51; BD Biosciences) and flow cytometry as described previously (58). HIV-1 reactivation was measured as the percentage of GFP-positive cells by flow cytometry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathleen Boris-Lawrie, Patrick Green, Vineet KewalRamani, Baek Kim, Nathaniel Landau, Vicente Planelles, and Jian-Hua Wang for sharing reagents. We thank the members of the Wu and Musier-Forsyth labs for valuable discussions. The following reagents were obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: J-Lat full-length GFP cells (clone 9.2) from Eric Verdin and human rIL-2 from Maurice Gately, Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI104483, R01 AI120209, and R01 GM128212 to L.W., NIH grant R01 GM113887 to K.M.-F., C. Glenn Barber funds from the College of Veterinary Medicine at The Ohio State University (OSU) to J.M.A., NIH grant F31 GM119178 and a fellowship from the Center for RNA Biology at OSU to A.A.D., NIH grant T32 GM007223 and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship to O.B., and NIH grant T32 GM008283 to K.M.K.

L.W. conceived the study and designed experiments with J.M.A. and C.S.G. J.M.A., S.H.K., S.B., and T.-W.L. performed the experiments. O.B. and K.M.K. purified recombinant SAMHD1 proteins. J.M.A., C.S.G., A.A.D., K.M.-F., Y.X., and L.W. analyzed data. J.M.A. and L.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and revised the manuscript. All the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, Perrino FW. 2011. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem 286:43596–43600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.317628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HC, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LP, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, Webb M. 2011. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzolin E, Pontarin G, Rampazzo C, Miazzi C, Ferraro P, Palumbo E, Reichard P, Bianchi V. 2013. The deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a major regulator of DNA precursor pools in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:14272–14277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312033110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, Margottin-Goguet F. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol 13:223–228. doi: 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramberg T, Kahle T, Bloch N, Wittmann S, Mullers E, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Kim B, Lindemann D, Landau NR. 2013. Restriction of diverse retroviruses by SAMHD1. Retrovirology 10:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim ET, White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Diaz-Griffero F, Weitzman MD. 2013. SAMHD1 restricts herpes simplex virus 1 in macrophages by limiting DNA replication. J Virol 87:12949–12956. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02291-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hollenbaugh JA, Gee P, Baker J, Daly MB, Amie SM, Tate J, Kasai N, Kanemura Y, Kim DH, Ward BM, Koyanagi Y, Kim B. 2013. Host factor SAMHD1 restricts DNA viruses in non-dividing myeloid cells. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003481. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Zhu M, Pan X, Zhu Y, Yan H, Jiang T, Shen Y, Dong X, Zheng N, Lu J, Ying S. 2014. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by SAMHD1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 450:1462–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong GU, Park IH, Ahn K, Ahn BY. 2016. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by a dNTPase-dependent function of the host restriction factor SAMHD1. Virology 495:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommer AF, Rivière L, Qu B, Schott K, Riess M, Ni Y, Shepard C, Schnellbächer E, Finkernagel M, Himmelsbach K, Welzel K, Kettern N, Donnerhak C, Münk C, Flory E, Liese J, Kim B, Urban S, König R. 2016. Restrictive influence of SAMHD1 on hepatitis B virus life cycle. Sci Rep 6:26616. doi: 10.1038/srep26616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. 2011. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2011. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Descours B, Cribier A, Chable-Bessia C, Ayinde D, Rice G, Crow Y, Yatim A, Schwartz O, Laguette N, Benkirane M. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 reverse transcription in quiescent CD4+ T-cells. Retrovirology 9:87. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldauf HM, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, Konig R, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat Med 18:1682–1687. doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beloglazova N, Flick R, Tchigvintsev A, Brown G, Popovic A, Nocek B, Yakunin AF. 2013. Nuclease activity of the human SAMHD1 protein implicated in the Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and HIV-1 restriction. J Biol Chem 288:8101–8110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.431148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tüngler V, Staroske W, Kind B, Dobrick M, Kretschmer S, Schmidt F, Krug C, Lorenz M, Chara O, Schwille P, Lee-Kirsch MA. 2013. Single-stranded nucleic acids promote SAMHD1 complex formation. J Mol Med (Berl) 91:759–770. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-0995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goncalves A, Karayel E, Rice GI, Bennett KL, Crow YJ, Superti-Furga G, Bürckstümmer T. 2012. SAMHD1 is a nucleic-acid binding protein that is mislocalized due to Aicardi-Goutières syndrome-associated mutations. Hum Mutat 33:1116–1122. doi: 10.1002/humu.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seamon KJ, Bumpus NN, Stivers JT. 2016. Single-stranded nucleic acids bind to the tetramer interface of SAMHD1 and prevent formation of the catalytic homotetramer. Biochemistry 55:6087–6099. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryoo J, Choi J, Oh C, Kim S, Seo M, Kim SY, Seo D, Kim J, White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Diaz-Griffero F, Yun CH, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim B, Baek D, Ahn K. 2014. The ribonuclease activity of SAMHD1 is required for HIV-1 restriction. Nat Med 20:936–941. doi: 10.1038/nm.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seamon KJ, Sun Z, Shlyakhtenko LS, Lyubchenko YL, Stivers JT. 2015. SAMHD1 is a single-stranded nucleic acid binding protein with no active site-associated nuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res 43:6486–6499. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonucci JM, St Gelais C, de Silva S, Yount JS, Tang C, Ji X, Shepard C, Xiong Y, Kim B, Wu L. 2016. SAMHD1-mediated HIV-1 restriction in cells does not involve ribonuclease activity. Nat Med 22:1072–1074. doi: 10.1038/nm.4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wittmann S, Behrendt R, Eissmann K, Volkmann B, Thomas D, Ebert T, Cribier A, Benkirane M, Hornung V, Bouzas NF, Gramberg T. 2015. Phosphorylation of murine SAMHD1 regulates its antiretroviral activity. Retrovirology 12:103. doi: 10.1186/s12977-015-0229-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonucci JM, St Gelais C, Wu L. 2017. The dynamic interplay between HIV-1, SAMHD1, and the innate antiviral response. Front Immunol 8:1541. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. 2013. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep 3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, Diaz-Griffero F. 2013. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe 13:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welbourn S, Dutta SM, Semmes OJ, Strebel K. 2013. Restriction of virus infection but not catalytic dNTPase activity is regulated by phosphorylation of SAMHD1. J Virol 87:11516–11524. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01642-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.St Gelais C, de Silva S, Hach JC, White TE, Diaz-Griffero F, Yount JS, Wu L. 2014. Identification of cellular proteins interacting with the retroviral restriction factor SAMHD1. J Virol 88:5834–5844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00155-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang F, St Gelais C, de Silva S, Zhang H, Geng Y, Shepard C, Kim B, Yount JS, Wu L. 2016. Phosphorylation of mouse SAMHD1 regulates its restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, but not murine leukemia virus infection. Virology 487:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonifati S, Daly MB, St Gelais C, Kim SH, Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim DH, Schinazi RF, Kim B, Wu L. 2016. SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1 infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology 495:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen L, Kim B, Brojatsch J, Diaz-Griffero F. 2013. Contribution of SAM and HD domains to retroviral restriction mediated by human SAMHD1. Virology 436:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji X, Wu Y, Yan J, Mehrens J, Yang H, DeLucia M, Hao C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J, Ahn J, Xiong Y. 2013. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SAMHD1 by dGTP. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:1304–1309. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruelas DS, Greene WC. 2013. An integrated overview of HIV-1 latency. Cell 155:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman DD, Margolis DM, Delaney M, Greene WC, Hazuda D, Pomerantz RJ. 2009. The challenge of finding a cure for HIV infection. Science 323:1304–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1165706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shan L, Yang HC, Rabi SA, Bravo HC, Shroff NS, Irizarry RA, Zhang H, Margolick JB, Siliciano JD, Siliciano RF. 2011. Influence of host gene transcription level and orientation on HIV-1 latency in a primary-cell model. J Virol 85:5384–5393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02536-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margolis DM, Garcia JV, Hazuda DJ, Haynes BF. 2016. Latency reversal and viral clearance to cure HIV-1. Science 353:aaf6517. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Lint C, Bouchat S, Marcello A. 2013. HIV-1 transcription and latency: an update. Retrovirology 10:67. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Araínga M, Edagwa B, Mosley RL, Poluektova LY, Gorantla S, Gendelman HE. 2017. A mature macrophage is a principal HIV-1 cellular reservoir in humanized mice after treatment with long acting antiretroviral therapy. Retrovirology 14:17. doi: 10.1186/s12977-017-0344-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abbas W, Tariq M, Iqbal M, Kumar A, Herbein G. 2015. Eradication of HIV-1 from the macrophage reservoir: an uncertain goal? Viruses 7:1578–1598. doi: 10.3390/v7041578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar A, Abbas W, Herbein G. 2014. HIV-1 latency in monocytes/macrophages. Viruses 6:1837–1860. doi: 10.3390/v6041837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bosque A, Planelles V. 2009. Induction of HIV-1 latency and reactivation in primary memory CD4+ T cells. Blood 113:58–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finzi D, Hermankova M, Pierson T, Carruth LM, Buck C, Chaisson RE, Quinn TC, Chadwick K, Margolick J, Brookmeyer R, Gallant J, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Richman DD, Siliciano RF. 1997. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278:1295–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonucci JM, Kim SH, St. Gelais C, Bonifati S, Buzovetsky O, Knecht K, Duchon AA, Xiong Y, Musier-Forsyth KM, Wu L. 2018. SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 gene expression and reactivation of viral latency in CD4+ T-cells. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/270843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Shifera AS, Hardin JA. 2010. Factors modulating expression of Renilla luciferase from control plasmids used in luciferase reporter gene assays. Anal Biochem 396:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen CA, Pavlakis GN. 1990. Tat and Rev: positive regulators of HIV gene expression. AIDS 4:A51. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andresen V, Pise-Masison CA, Sinha-Datta U, Bellon M, Valeri V, Washington Parks R, Cecchinato V, Fukumoto R, Nicot C, Franchini G. 2011. Suppression of HTLV-1 replication by Tax-mediated rerouting of the p13 viral protein to nuclear speckles. Blood 118:1549–1559. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-293340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jordan A, Bisgrove D, Verdin E. 2003. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. EMBO J 22:1868–1877. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spina CA, Anderson J, Archin NM, Bosque A, Chan J, Famiglietti M, Greene WC, Kashuba A, Lewin SR, Margolis DM, Mau M, Ruelas D, Saleh S, Shirakawa K, Siliciano RF, Singhania A, Soto PC, Terry VH, Verdin E, Woelk C, Wooden S, Xing S, Planelles V. 2013. An in-depth comparison of latent HIV-1 reactivation in multiple cell model systems and resting CD4+ T cells from aviremic patients. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003834. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Silva S, Hoy H, Hake TS, Wong HK, Porcu P, Wu L. 2013. Promoter methylation regulates SAMHD1 gene expression in human CD4+ T cells. J Biol Chem 288:9284–9292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.447201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf M, LeVine H, May WS, Cuatrecasas P, Sahyoun N. 1985. A model for intracellular translocation of protein kinase C involving synergism between Ca2+ and phorbol esters. Nature 317:546–549. doi: 10.1038/317546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blumberg PM. 1988. Protein kinase C as the receptor for the phorbol ester tumor promoters: sixth Rhoads memorial award lecture. Cancer Res 48:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Folks TM, Clouse KA, Justement J, Rabson A, Duh E, Kehrl JH, Fauci AS. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor alpha induces expression of human immunodeficiency virus in a chronically infected T-cell clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:2365–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Duh EJ, Maury WJ, Folks TM, Fauci AS, Rabson AB. 1989. Tumor necrosis factor alpha activates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through induction of nuclear factor binding to the NF-κB sites in the long terminal repeat. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:5974–5978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siliciano RF, Greene WC. 2011. HIV latency. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 1:a007096. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rye-McCurdy T, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. 2015. Fluorescence anisotropy-based salt-titration approach to characterize protein-nucleic acid interactions. Methods Mol Biol 1259:385–402. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2214-7_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bosque A, Planelles V. 2011. Studies of HIV-1 latency in an ex vivo model that uses primary central memory T cells. Methods 53:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li C, Wang HB, Kuang WD, Ren XX, Song ST, Zhu HZ, Li Q, Xu LR, Guo HJ, Wu L, Wang JH. 2017. Naf1 regulates HIV-1 latency by suppressing viral promoter-driven gene expression in primary CD4+ T cells. J Virol 91:e01830-. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01830-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen S, Bonifati S, Qin Z, St Gelais C, Kodigepalli KM, Barrett BS, Kim SH, Antonucci JM, Ladner KJ, Buzovetsky O, Knecht KM, Xiong Y, Yount JS, Guttridge DC, Santiago ML, Wu L. 2018. SAMHD1 suppresses innate immune responses to viral infections and inflammatory stimuli by inhibiting the NF-κB and interferon pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E3798–E3807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801213115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.St Gelais C, Coleman CM, Wang JH, Wu L. 2012. HIV-1 Nef enhances dendritic cell-mediated viral transmission to CD4+ T cells and promotes T-cell activation. PLoS One 7:e34521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Finzi D, Blankson J, Siliciano JD, Margolick JB, Chadwick K, Pierson T, Smith K, Lisziewicz J, Lori F, Flexner C, Quinn TC, Chaisson RE, Rosenberg E, Walker B, Gange S, Gallant J, Siliciano RF. 1999. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat Med 5:512–517. doi: 10.1038/8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Taube R, Fujinaga K, Wimmer J, Barboric M, Peterlin BM. 1999. Tat transactivation: a model for the regulation of eukaryotic transcriptional elongation. Virology 264:245–253. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karn J, Dingwall C, Finch JT, Heaphy S, Gait MJ. 1991. RNA binding by the tat and rev proteins of HIV-1. Biochimie 73:9–16. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90068-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaudray G, Gachon F, Basbous J, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Devaux C, Mesnard JM. 2002. The complementary strand of the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 RNA genome encodes a bZIP transcription factor that down-regulates viral transcription. J Virol 76:12813–12822. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12813-12822.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W, Nisbet JW, Albrecht B, Ding W, Kashanchi F, Bartoe JT, Lairmore MD. 2001. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 p30(II) regulates gene transcription by binding CREB binding protein/p300. J Virol 75:9885–9895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.20.9885-9895.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sørensen KD, Sørensen AB, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kunder S, Schmidt J, Pedersen FS. 2005. Distinct roles of enhancer nuclear factor 1 (NF1) sites in plasmacytoma and osteopetrosis induction by Akv1-99 murine leukemia virus. Virology 334:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu L. 2013. Cellular and biochemical mechanisms of the retroviral restriction factor SAMHD1. ISRN Biochem 2013:728392. doi: 10.1155/2013/728392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.St Gelais C, de Silva S, Amie SM, Coleman CM, Hoy H, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim B, Wu L. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in dendritic cells (DCs) by dNTP depletion, but its expression in DCs and primary CD4+ T-lymphocytes cannot be upregulated by interferons. Retrovirology 9:105. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arnold LH, Groom HC, Kunzelmann S, Schwefel D, Caswell SJ, Ordonez P, Mann MC, Rueschenbaum S, Goldstone DC, Pennell S, Howell SA, Stoye JP, Webb M, Taylor IA, Bishop KN. 2015. Phospho-dependent regulation of SAMHD1 oligomerisation couples catalysis and restriction. PLoS Pathog 11:e1005194. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tang C, Ji X, Wu L, Xiong Y. 2015. Impaired dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 by phosphomimetic mutation of Thr-592. J Biol Chem 290:26352–26359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Skowronski J. 2013. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem 288:10406–10417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thaker YR, Schneider H, Rudd CE. 2015. TCR and CD28 activate the transcription factor NF-κB in T-cells via distinct adaptor signaling complexes. Immunol Lett 163:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schütze S, Wiegmann K, Machleidt T, Krönke M. 1995. TNF-induced activation of NF-κB. Immunobiology 193:193–203. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang JH, Janas AM, Olson WJ, KewalRamani VN, Wu L. 2007. CD4 coexpression regulates DC-SIGN-mediated transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 81:2497–2507. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01970-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panfil AR, Al-Saleem J, Howard CM, Mates JM, Kwiek JJ, Baiocchi RA, Green PL. 2015. PRMT5 is upregulated in HTLV-1-mediated T-cell transformation and selective inhibition alters viral gene expression and infected cell survival. Viruses 8:E7. doi: 10.3390/v8010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dong C, Kwas C, Wu L. 2009. Transcriptional restriction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gene expression in undifferentiated primary monocytes. J Virol 83:3518–3527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02665-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ji X, Tang C, Zhao Q, Wang W, Xiong Y. 2014. Structural basis of cellular dNTP regulation by SAMHD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:E4305–E4314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412289111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jones CP, Datta SA, Rein A, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. 2011. Matrix domain modulates HIV-1 Gag's nucleic acid chaperone activity via inositol phosphate binding. J Virol 85:1594–1603. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01809-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stewart-Maynard KM, Cruceanu M, Wang F, Vo MN, Gorelick RJ, Williams MC, Rouzina I, Musier-Forsyth K. 2008. Retroviral nucleocapsid proteins display nonequivalent levels of nucleic acid chaperone activity. J Virol 82:10129–10142. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01169-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.St Gelais C, Roger J, Wu L. 2015. Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein negatively regulates HIV-1 infection in CD4+ T cells. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 31:806–816. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]