Abstract

Background

Group model building (GMB) is an approach to building qualitative and quantitative models with stakeholders to learn about the interrelationships among multilevel factors causing complex public health problems over time. Scant literature exists on adapting this method to address public health issues that involve racial dynamics.

Objectives

This study’s objectives are to (1) introduce GMB methods, (2) present a framework for adapting GMB to enhance cultural responsiveness, and (3) describe outcomes of adapting GMB to incorporate differences in racial socialization during a community project seeking to understand key determinants of community violence transmission.

Methods

An academic–community partnership planned a 1-day session with diverse stakeholders to explore the issue of violence using GMB. We documented key questions inspired by critical race theory (CRT) and adaptations to established GMB “scripts” (i.e., published facilitation instructions). The theory’s emphasis on experiential knowledge led to a narrative-based facilitation guide from which participants created causal loop diagrams. These early diagrams depict how violence is transmitted and how communities respond, based on participants’ lived experiences and mental models of causation that grew to include factors associated with race.

Conclusions

Participants found these methods useful for advancing difficult discussion. The resulting diagrams can be tested and expanded in future research, and will form the foundation for collaborative identification of solutions to build community resilience. GMB is a promising strategy that community partnerships should consider when addressing complex health issues; our experience adapting methods based on CRT is promising in its acceptability and early system insights.

Keywords: Community health partnerships, health disparities, process issues, politics, education, sociology and social phenomena, community health research

Public health issues that are complex and messy are challenging to address. Violence is “complex”—it is shaped by risk and protective factors with non-linear relationships operating across multiple levels over time.1,2 Furthermore, empirical evidence indicates that interpersonal violence is often inseparable and has complex relationships with structural violence that manifests as racism, concentrated poverty, and social immobility.3–6 Violence is also “messy”— stakeholders have diverse perspectives and are in disagreement about how to (or even if we should) address it.7,8

Many valuable approaches exist that provide guidance for community mobilization9 and managing group decision making.10,11 Some approaches are useful for tackling issues that exhibit complexity and require engagement of stakeholders who have diverse perspectives about priority actions.12 For example, GMB is a stakeholder-engaged systems science approach developed to explore complex and messy issues (often focusing on capacity building).13,14 During GMB, facilitators guide participants to elicit their knowledge and develop and learn from visual and computational models about factors influencing a problem of interest over time.15 The process involves exploring mental models and challenging assumptions to gain insight about multilevel interrelated factors.12,16

GMB may be useful to engage with stakeholders around racism and violence because incomplete mental models17 and implicit biases due to race18 likely contribute to the debate that often surrounds discourse on racial disparities in violence. However, additional guidance is needed for group facilitation when issues of racism and unconscious stereotyping may surface, in real time. Discussions can become heated in light of issues such as historical and ongoing issues of racial segregation and discrimination. Individuals have a range of perspectives on approaching race relations—from that of “color blindness” (the notion that effects of race can be dissolved) to race consciousness (the belief that racial justice must be confronted deliberately and directly).19–21

To address an issue that involves the aforementioned racial dynamics, careful consideration is required to understand connections between racism and violence and improve racial and cultural sensitivity. CRT provides a framework for critical analysis of how race and racism are engrained in social structures and influence the lives of racial minorities.22 Tenets of CRT include intercentricity of race and racism with other forms of subordination, challenge of dominant ideology, commitment to social justice, centrality of experiential knowledge, and transdisciplinary perspective.22 The insights and ideas espoused within CRT literature are well-aligned with concepts of “messy” and “complex” problems. For example, intercentricity of race recognizes that complex relationships exist among race, class, and gender and that racism plays out across multiple levels (individual, interpersonal, institutional).20,21,23

Although GMB is an emerging method for addressing community health issues,24–27 scant literature exists that specifically focuses on the process when addressing issues that involve racial or sociocultural dynamics. Our goal is to describe our process to develop, adapt, and apply GMB methods to address the issue of violence. Specifically, we aim to describe how our community–academic team considered tenets of CRT to adapt and develop new GMB scripts and discuss the insights gained.

Methods

Setting and Community Background

Rochester, New York, is the anchor for a metropolitan area spanning nine counties.28 In 2013, the population was 43.7% White and 41.7% African American.28 The metro area is noted as the fifth poorest city in the United States,29 and the area has significantly high rates of racial segregation. African Americans are far more likely to be poor (35% of African Americans have poverty-level incomes compared with 10% of Whites)30 and live in one of Rochester’s highly concentrated extremely poor urban neighborhoods.29

Underlying Rochester’s socioeconomic disparities is a long history of tense race relations and sociopolitical events that have shaped issues of violence.31 Crime statistics show a persistent violence epidemic above the national average. Racial and geographic disparities in violence are documented, with higher rates of violent crime in predominantly African American neighborhoods with concentrated poverty.32 These disparities are intricately tied to structural violence, institutional racism, and social injustices.

Initiating a Community Conversation to Address Violence

Past community-engaged research projects in Rochester, New York,33,34 raised awareness of the need for collective action to address violence. In 2013, in the aftermath of a homicide–suicide receiving national attention, two University of Rochester faculty members and a long-standing community partner from the Mental Health Association of Rochester came together to initiate a collaborative effort. They invited additional faculty and postdoctoral researchers to form an operational team for planning, which included three team members who were “Rochestarians” from childhood (one White and two African American).

The team met biweekly over 9 months to prepare for a 1-day session with the goal of developing a deeper understanding of violence and racial inequities as a foundation for future efforts. Through the planning process, the team used principles of community-based participatory research.9 In recognition of the community as a unit of identity, the team compiled an invitation list of stakeholders that would represent the community’s experiences with violence, including professionals responding to violence (i.e., law enforcement, faith community leaders) and community members with lived experiences of violence victimization. Stakeholders were sent an e-invite and planning team members followed up with phone calls to secure RSVPs.

The team sought to equitably involve community members. The lead academic and community partners asked community stakeholders who were unable to join regularly scheduled meetings to review planning outputs (e.g., agendas, scripts). Their feedback was reviewed during team meetings and used to refine outputs. All materials were reviewed as a group, and consensus was reached for final decisions. The community’s strengths were also considered. For example, the community partner on the planning team had decades of experience working within racially diverse partnerships, and led forthright discussions to address racial biases and inequities.

Adapting GMB Strategies Using CRT

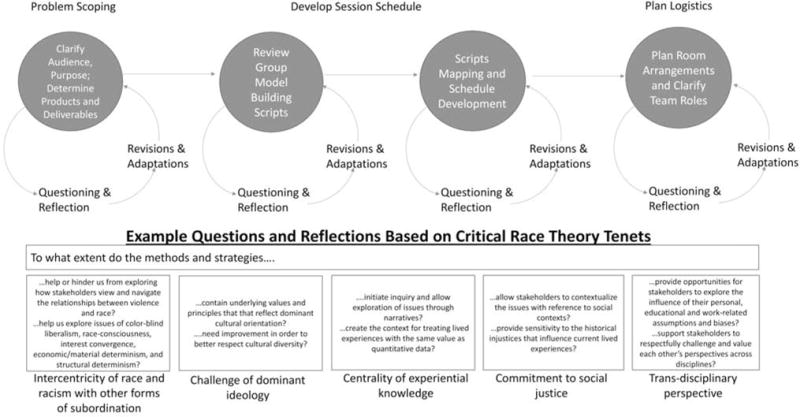

The team’s planning process for the one-day session involved four phases: (1) problem scoping, (2) review of GMB scripts (published descriptions of convergent, divergent, ranking, and prioritization group facilitation tasks),35 (3) scripts mapping, and (4) logistical planning (Figure 1).13,16,36 Meetings were co-facilitated by two academic team members, one local faculty lead and one faculty with GMB experience. Many materials and outputs were drafted, critically reviewed using CRT, and finalized during meetings. For example, team members drafted a statement of purpose, reviewed published descriptions of GMB scripts,35 and outlined the session agenda (Figure 2). As needed, team members were assigned to lead development of materials, which were subsequently reviewed as a group using CRT as a guiding framework.

Figure 1. The GMB planning and CRT reflection process.

The figure outlines the overarching GMB planning process, and the iterative process we used to reflect and consider how to adapt and plan strategies using CRT. The figure also indicates the tenets of CRT and examples questions we used throughout the process.

Figure 2. One-day session schedule.

The internal agenda provides a synopsis of the one-day session events. This includes the time spent on each respective topic as well as the major talking points and GMB scripts used.

The team used CRT to determine strategies that would facilitate open, respectful dialogue around violence including issues of racism. During at least two planning meetings for each of the four phases, the team included a critical questioning and reflection process. The process involved examining all phase outputs and materials in relation to questions based on the core tenets of CRT, and led to iterative adaption and refinement of our strategies. For example, after reviewing GMB scripts, we asked CRT-guided questions such as “to what extent do the methods initiate inquiry and allow exploration of issues through narratives?” The team reached a consensus that available scripts did not adequately engage participants through narratives, and one academic team member led development of a new script that would engage participants with vignettes (Appendix A). The script was reviewed and refined during subsequent meetings and re-questioned using CRT (see Figure 1 for additional questions), which resulted in additional refinements (e.g., types of violence and social contexts described in the vignettes).

After group discussion of session goals and initial reviews of published scripts, one team member drafted a ScriptsMap37 (Figure 3). Scripts mapping is a technique to assess and identify the set of scripts to use and in what order to help a facilitator guide a group through initiating, building, and interpreting system models. We used the ScriptsMap to align scripts (and their outputs and deliverables) with session goals, which guided finalization of script choices.

Figure 3. “Scripts Map” for a one-day session outlining the scripts, outcomes, and key deliverables.

The “Scripts Map” follows conventions and guidelines from GMB literature37 to lay out the sequence of scripts for the one-day session. This includes an indication of each script used in boxes with an arrow outward indicating the output product or deliverable (in ovals). Our map indicates how we brought together deliverables from the “Hopes and Fears” script—used early in the session—with deliverables from the “Problem Framing with a Vignettes” scripts to end the session with outlining our next steps.

Description of GMB Methods with CRT Adaptations

Causal Loop Diagramming Orientation Materials

While GMB research shows that participants can be readily taught how to develop causal loop diagrams,38 community and academic team members expressed concern that presentation of the technical diagramming language with didactic information and example diagrams may convey a message of “expert instructing the unskilled” that could exacerbate power differences among the participants with diverse backgrounds. Team members thought an orientation to diagramming that used story-telling was a less edifying approach.

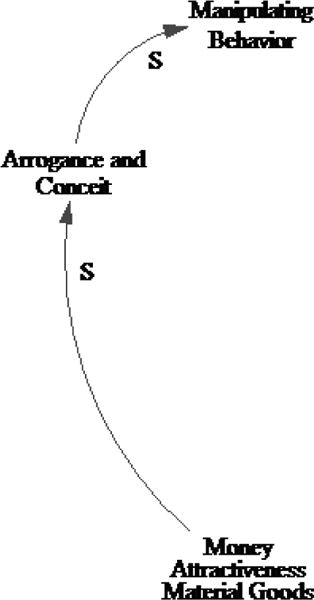

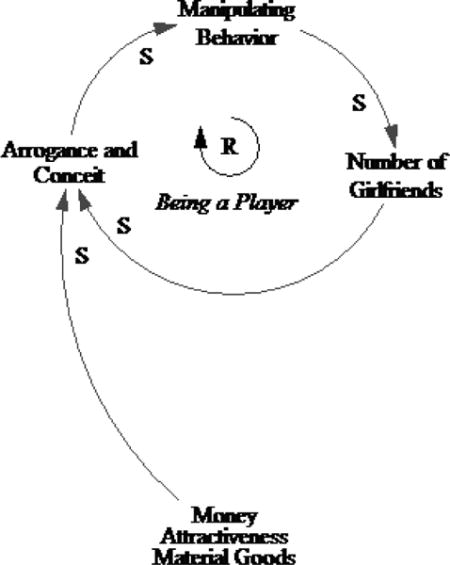

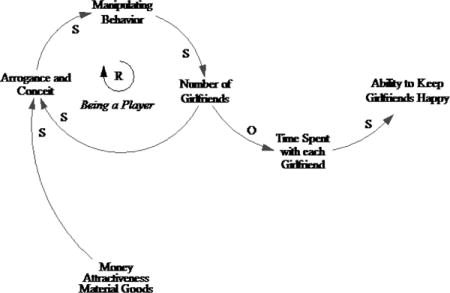

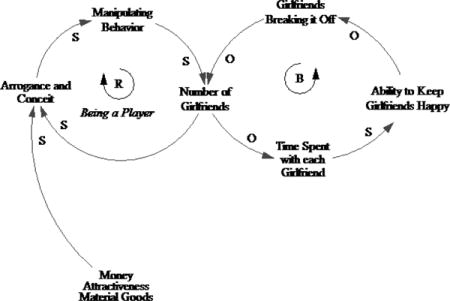

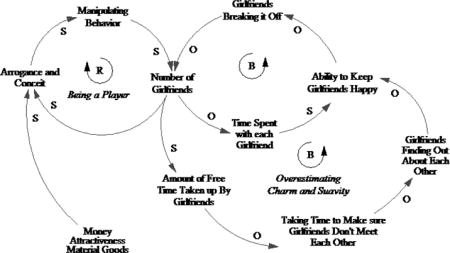

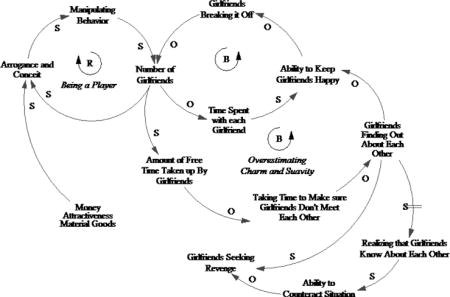

A 2-page handout introduced causal loop diagramming notation via a story titled, “The Player” (Appendix B). The plot follows an attractive and wealthy man who dates multiple women, but in the end is caught and his life unravels. Several stories were discussed with community partners, and “The Player” was chosen because it was relatable across diverse participants and amenable to diagramming notation. The handout diagrammed the story step-by-step, while introducing key notation and concepts. Participants received the handout 1 week before (and also reviewed at the beginning of) the 1-day session.

Addressing Intra-personal and Inter-personal Differences

GMB literature acknowledges the importance of facilitation skills to moderate interpersonal interactions and provides techniques to manage group dialogue.12 However, guidance is limited in addressing the differential individual experience of the social environment across racial groups as indicated by CRT.20,39 We sought scripts to reinforce the team’s ability to maintain participants’ active engagement and support for being “fully present” while allowing critical self-consciousness about personal privilege and racial identities.20 We identified and adapted a locally applied technique for self-reflection and safe engagement of others.

“Gracious Space” is a flexible model for facilitation, which has been used across many settings to have productive conversations around difficult topics.40 The approach promotes intentional self-reflection and productive conversation around disagreements. Through a decade of community-building and organizing efforts, our community partners developed a locally relevant version, including a specific “code word” introduced at the beginning of the 1-day session that allowed participants to prompt group discussion as needed (locally adapted Gracious Space guidelines available in Appendix C). Participants were encouraged to say “ouch” at any time during group discussion if another’s comment caused hurt. This cued the group about conflict. The GMB moderator could then stop, reflect, and discuss the conflict with the goal of maintaining the full presence and participation of the hurt individual and others that may have been offended. The team set a tenor to call Gracious Space a covenant—not “ground rules.” Rules imply punitive remedies as opposed to being open and accountable to learn from one another.

Engaging Participants through Vignettes of Lived Experiences

Participants had considerable variation in personal and community experiences of violence. CRT, however, calls for engagement using narrative methods that are firmly grounded in personal experience of the topic of interest.21 Stories present complexity of lived experiences, for instance, of intermingling individual and community or cultural strengths as well as challenges in light of violence exposure. We developed a new script to engage participants around the issue of violence transmission using a narrative approach.

The new script, “Problem Framing With a Vignette” (Appendix A), guided facilitators in engaging stakeholders to collectively frame the issue and elicit initial variables to diagram in a manner that recognized the importance of lived experiences. The new script used vignettes, or composite and anonymous case studies of individuals’ experiences of violence from the community, from a variety of racial backgrounds. The planning team developed three distinct vignettes to ensure group discussion touched on many key aspects of violence. The script’s instructions guided participants to read vignettes and reflect on them individually. As participants reflected, they identified dynamic relationships by answering the following statement with numerous examples: “What stood out to me most about this vignette was that _________ led to _________.” The facilitator then used a nominal group technique where participants shared, identified themes and connections across responses, and prioritized statements to use for initiating a diagram that would further explore system structure. The availability of multiple vignettes as possible seed conversation starters enabled flexibility. Facilitators could follow the interest and expertise of group participants as the day unfolded.

One-Day Session Overview

In October 2014, we held the 1-day session. In addition to the 6-member core planning team, 27 individuals participated: 11 were from academic research settings and 16 were community partners representing law enforcement, schools, housing, grassroots community organizations, religious institutions, and prior gang-involved youth. Participants were diverse in gender and race. A post-satisfaction survey was fielded and completed by nine participants, who all provided favorable responses. Additional qualitative feedback was also collected. For example, Table 1 presents one community member’s self-report of the experience of each methodological innovation (who we subsequently invited to co-author this paper).

Table 1.

Participant Feedback on Innovative GMB Practices to Address Racial Inequities in Violence

| Element |

| Ice-breaker question on personal experiences with resiliency to raise awareness of similarities and differences of privilege: (1) asks participants to note who or what was a positive force in their life when they had to work through difficulties, (2) uses a simple question to allow participants to see similarities as well as differences in the experience of facing challenges and coping strategies and to emphasize strengths, and (3) has people speak from experience first to see one another in their life course as compared with introductions that emphasize formal power hierarchies (e.g., job titles). |

| How It Was Experienced |

| “The ice-breaker question in the introduction was created to foster dialogue with a focal point of resiliency but did not expound on how to carry these traits to the targeted population. I started to think, how could this ice-breaker question [about resilience] start to address the question of violence in the community? The question could be answered differently by people that live in communities where violence is so prevalent—that seeing and hearing about death as a result of violence is ‘par for the course.’ Funerals are daily for people dying young and many are dying in their 50s and 60s of substance abuse disorders, mental health, and lack of necessities that most of us take for granted. When I answered the [ice-breaker] question, I felt both the positive and the powerlessness around the topic of resiliency when answering the question. I remembered how insignificant that I felt about the inequity of a situation that a teacher helped to make positive [for me]. I felt powerless when the teacher told me there was really nothing I could do about the white child getting the award who had lower grades. She affirmed that my grades were good, I was doing okay, and there were some things we can’t do anything about, but we can keep going on. This is a story she said I would tell in college. No matter what, she said, they can’t take your grades away from you, internally. I actually felt that ‘less than‘ feeling as an adult that I could not have described as a child. All of the above were my thoughts when answering this question. I guess I can say with honesty that this opened my mind to a clearer awareness that most of the people sitting around the table probably didn’t feel as I did.” |

| Methodological Insights |

| In the same community, people come to the table with different personal histories of resilience and privilege. For some at the table, exposure to violent deaths is ubiquitous, for others at the table, not. The emotional experience of having awareness of such differences was, for a participant, reminiscent of early life experiences with racial injustice. |

| Element |

| GMB hopes and fears script uses open-ended brainstorming and facilitated discussion to allow participants to voice their expectations and concerns about pursuing a group model-building project. |

| How It Was Experienced |

| “When I listed my hopes and fears they were not too much different than when I was a child—that because of the color of my skin and the size of my bank account, I am still not valued by the content of my character. My hope was much like it was when I was young that white people would be different and fair. My family was one of the many in the Great Migration from the south to the north—the imagined life of freedom, in particular, California and New York states. There was not too much difference though. As a child I felt enormously relieved that I was no longer segregated in a town in the south. Colored Town, where I spent most of my very young childhood, was in the recesses of my memories. ‘Where do we go next and what steps do we continue to take?’ is a script that I have used to pragmatically plan, work, and build my life and work with families in communities who lack these skills. The issue of transforming violence can be handled by redemption and sources of strength from something greater than oneself as the next step in many lives (of violence survivors). Using Mindful Meditation to calm down the injustices of the poor carries me over to plan the next step in helping transform my life and the lives of those whose hardship resemble mine but are not mine. My lived experiences are perceptually different. I say this because many people view and live through daunting violence and seemingly come out unscathed. Of course, they are not, but they are able to find a locus of control within them and say ‘there is hope and things will be different for me and my family.’ So we must be careful when we talk about lived experiences of people since they all are interpreted individually. I fear that structural racism and violence is a residue of historical trauma and slavery. And my hope is that we can generate a springboard to overcome these factors by listening to people in the community that withstood the storm. These are the thoughts I had in response to the probe. We are talking about tough issues in the neighborhoods.” |

| Methodological Insights |

| The Hopes and Fears script is culturally congruent and culturally responsive. It mimics a framework for daily coping with violence among those with lived experiences including structural violence. |

| Element |

| System dynamics GMB (overall approach): (1) offers an approach to study the context and dynamics around a complex systems problem, (2) focuses on identifying more impactful and supportable solutions to community problems grounded in rich and shared understanding of the causal structure of the system creating the behavior of interest (e.g., violence transmission), and (3) enables diverse viewpoints to be addressed and incorporated into system structure. |

| How It Was Experienced |

| “Sometimes [it] is hard for me to be grateful for the scanty diversity that is offered around community engagement and having forums to invite the community in to discuss the methodology tools, and research. I am relieved that [it] is better than it used to be. Days like that day are hopeful and encourage building models to do the work. To do the work we need to do, we need to engage the community on a different level. We need to have a component where the community comes to the institution to develop instruments to measure the aims and goals of the researcher. Positive relationships, and stories, in community are used to investigate and find out our new awakenings. While we were building our model, in my mind, we were building our community by allowing our community to participate in the model. People need a safe environment to examine community issues that most of us feel are the risk factors. They need to examine histories and come to terms. And learn to live through them. This is what was asked of me in the model building.” “Despite being a resilient survivor, and being able to reach out at critical turning points in my life, I don’t feel the equality and peace that Dr. King aimed for during the Civil Rights Movement. The timing of all the deaths by Whites on Blacks, and the senseless murders that African American young men commit against each other is very harrowing. The methods used co-created Causal Loop Diagrams of Community Violence, and explored many tenets of how violence is transmitted. I found it useful and a tool that created a method to unravel causes of violence and how mental health, fear and victimization has a causal effect on everyone. Violence begets violence is indicative of how people were assimilated into a violent and downcast life style only to perpetrate these behaviors on the own families and community members. It started me to thinking, once again, what type of movement of miracle it is going to take for us to finally find the Exodus pathway out of historical trauma that so many of us or most of us are enduring and navigate [with] our inner resources.” |

| Methodological Insights |

| A strength of the diagramming approach was providing an avenue to explicitly explore complex causal mechanisms across time. For this participant, the issue still feels like a major obstacle and solutions remain unclear. Continued work to improve the diagrams and use them to identify solutions is a clear need. |

| Element |

| System diagramming orientation materials uses a story to introduce causal loop diagramming notation |

| How It Was Experienced |

| “The player loop diagram was useful for defining many causal effects of violence. In one perspective, it got me thinking about the domino effects of violence in the community. The player can create women:women violence. I thought about what I saw in communities, and the shame that being his victim can bring. The emotional trauma can lead to people committing violence acts—even if they are cursing him out. People also didn’t talk about why the player is the player. What are his root causes for being so diabolical?” “One other thing I noticed … The player being middle-class de-stigmatized the image of the ‘savage’ and ‘not so charismatic male of color’ that media portrays as the ‘end–all-creator-of-violence-and-evil’ in marginalized populations. It made me think of the hustler or the pimp. All kinds of things can be a player, and it conjured up different characters in the urban cities, in a negative and positive connotations. You don’t hear about Donald Trump being called the player, do you? But the community also looks at a ‘player’ like he is cool. That started me thinking about the different experiences that would need to be mapped. It gave me a smile inside that here the player wasn’t an African-American male. We are thinking about the player as universal.” |

| Methodological Insights |

| The orientation materials were useful to introduce the diagramming notation, but for this participant, also led to consideration of and connections to the issue of violence. |

| Element |

| Engaging participants through vignettes of lived experiences uses a narrative and story-telling approach to elucidate dynamic causes of violence, leverage points at which change can be targeted, and existing solutions/strengths among those experiencing violence |

| How It Was Experienced |

| “When I first thought about the story, I thought about what would be the cause of something so wicked and evil? What are the root issues that would lead a person to go in someone’s house and take their life? I thought about mental health co-morbidity with drug addiction as people are not pure evil. I also thought about how structural racism drives people to the brink to do horrible things. When they feel so powerless and don’t have money and basic necessities. I also thought of the effect. How the police would likely be looking for a black man in a case like this. A case like this would foster racial profiling, even though the race was not described in the vignette. It’s difficult to frame the complexities of undoing the residues and historical trauma of slavery and racism in the African American urban communities. Seemingly most of the problematic complexities are often highlighted and framed in a way that relates to the ‘Robbery’ vignette. I thought about how the police would probably profile a young man of color in their pursuit of justice.” |

| Methodological Insights |

| The vignettes allowed this participant to compare and contrast issues of violence to personal experiences and perspectives. |

| Element |

| Addressing intra- and inter-personal differences among participants when discussing the vignettes uses gracious space techniques during hard discussions to help participants address conflict and be authentically engaged in dialogue. |

| How It Was Experienced |

| Team observation: An “ouch” was raised by a respected community elder when a young African American man spoke of his rejection of a proposed policy that formerly incarcerated individuals receive higher education aid. Despite that elder’s disagreement with this opinion, the discussion process helped the community elder develop deeper insight and empathy toward the young man espousing this view, as seen in the feedback below. “The gracious space for me allowed the group to say ‘ouch’ when something hurt them when they didn’t agree on it. It provided space to talk about what people meant. It cleared up miscommunication. Disrespect. It made communication better.” “The new form of slavery in the criminal justice system, the underpinning of a racial caste system crystalized in the [group] discussion of racial inequities in the criminal justice system. It’s really sad because many of the judges only see the defendant and don’t care about the root causes. Of course this attitude fuels the economy of the Prison Industrial Complex, feeding off of generations of men and women of color and poor whites too. I often think that many African American males never had father figures and how this factor was prevalent in the slaves’ quarters since their fathers were sold at any given moment. There was really no family cohesiveness outwardly and inwardly the pain of endless separation, unnecessary violence meted out on a daily bases—the inner resilience that it took to bear that must have been the characteristic of the hope shot for the future. I thought about [when raising the ‘ouch’] how violence had to be used to subdue the rebellion in young men who have transferred violence to their own kin for lack of power and sheer frustrations. I thought about it more when the robbery scene was introduced. We oppress each other. But it’s all of us or none. It’s about embracing all people who have served their time. To be inclusive so people will have college and resources to step into the role of citizen and not being an ‘ex-offender.’ ” |

| Methodological Insights |

| The “ouch” conversation helped the community elder not blame or shame a member of their community for his feelings, and stay in solidarity with despite having different views. The elder came to understand, by remaining in respectful conversation with him, that these views [not wanting aid to be given] can emerge from his exposure to structural violence and the violence of suppression. |

Discussion

GMB is a novel strategy for community health partnerships for improving system insight and collaboration around complex and messy problems such as violence. With guidance from community partners, the planning team made theory-informed adaptations to GMB that improved the cultural relevance and engagement of diverse community members in a racially charged time. The methods were well-received by participants and provided a foundation for future collaboration.

Research on GMB has indicated the process can generate new insight regarding complex issues.38 We found the diagramming process helped identify potentially problematic perceptions among stakeholder’s mental models. For example, during diagramming, community stakeholders indicated restorative justice (i.e., a criminal justice system that provides rehabilitation for offenders) as an important solution; however, law enforcement stakeholders indicated they perceived a lack of community support for restorative justice. Such misperceptions can lead to underutilization of desired strategies. Further stakeholder-engaged diagramming can elucidate causes for divergent perspectives.

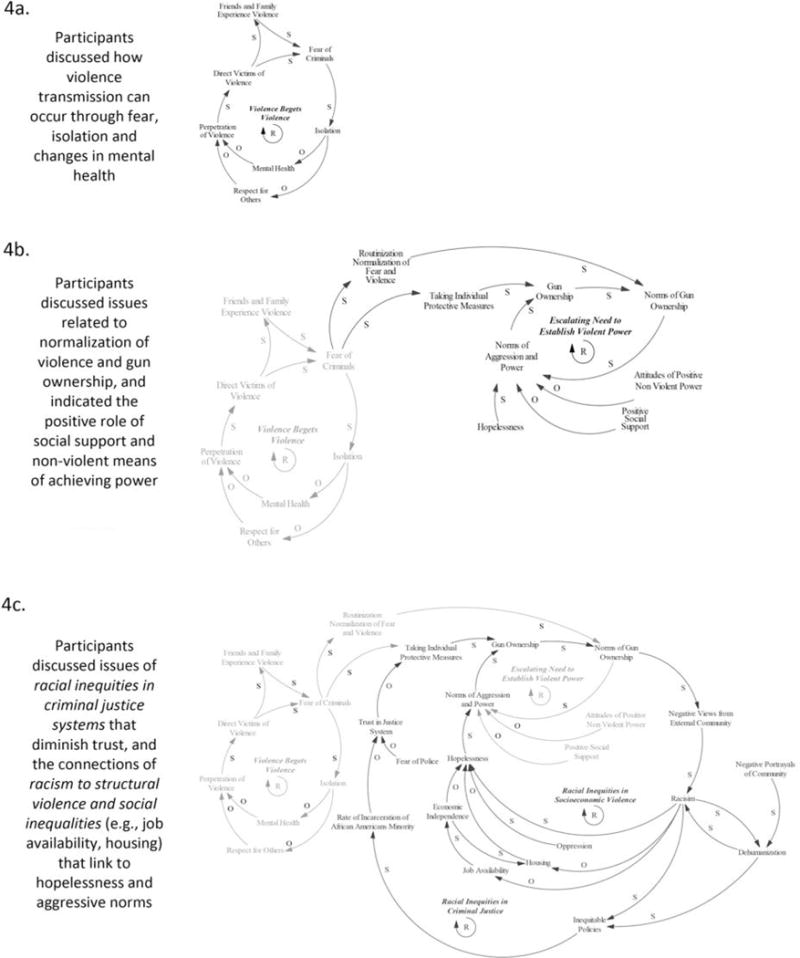

Our narrative-based approach revealed important insight about patterns of violence in the community, and prompted discussion of differential mindsets and biases. For example, one preliminary causal loop diagram (Figure 4) was based on a vignette about a home invasion and robbery that led to the survivor obtaining a gun. Interestingly, despite no mention of race in the narrative, participants began to assign race and wealth status to the vignette characters. Several African American participants noted the vignette did not match their community’s patterns of violence, noting “that must have been a wealthy neighborhood—crime like that doesn’t happen in the city.” They also noted that the absence of community support after the event (as portrayed in the vignette) was not likely the experience in communities in which violence is ever-present. There is evidence that positive neighborhood social support that can mitigate negative consequences of victimization exists in underserved communities, but is often overlooked by research that focuses on negative predictors of violence.41 The patterns concerning relationships between geography, race, and crime rates are complex,42 and our adapted methods seemed to illuminate the deeply engrained nature of race and racism in our society.

Figure 4. Preliminary co-created causal loop diagram of community violence.

The preliminary causal loop diagram is shown in three stages to exemplify major content discussed during the GMB session. The discussion evolved around three main areas of dynamics and feedback. In panel 3a, discussions of isolation and mental health are illustrated. In panel 3b, discussions evolved to that of gun ownership and the normalization of violence, but also indicated the positive role of social support. Finally, in panel 3c, discussions of racial inequalities and connections to structural violence are illustrated. In the diagram, a “S” is used to signify that a change in one variable causes the second variable to change in the same direction, a “O” is used to signify that a change in one variable causes the second variable to change in the opposite direction. An “R” with a clockwise arrow around it indicates closed sequences of causes and effects among variables that reinforce change in the same direction (i.e., a change in one variable will be lead to changes in other variables that ultimately lead to additional change in the original variable in the same direction).

We had rich discussions of racial inequalities and violence, but we also encountered challenges in the group facilitation and diagramming process. Participants appeared challenged to expound on mechanisms and elements underlying issues of racism and structural violence (Figure 4). Thus, much work remains to better represent some of the concepts (e.g., racism), add variables that are missing (e.g., substance abuse), and clarify links between elements. Time allotted contributed to this issue. The most ‘ouches’ were raised during discussions related to racism and we needed to attend more to group dynamics than diagramming tasks.

Our study has limitations. A relatively low number of surveys were completed, which were fielded at the end of the 7-hour session when participants were anxious to leave. We requested feedback from participants after the session, but information was provided informally. More rigorous evaluation and research would provide valuable information on how the process influences perceptions, commitment, and subsequent action.

Moving forward, the core planning team intends to use the preliminary diagrams to identify specific issues to explore and create refined models. The project will involve additional GMB sessions, collection and analysis of qualitative data (e.g., in-depth interviews, content analysis of documentaries regarding violence), and thorough literature reviews to refine and substantiate the causal loop diagrams. Using GMB scripts, we will present refined diagrams at a follow-up annual partnership meeting to help stakeholders identify priority strategies. Finally, we plan to use the diagrams to identify data that is missing and new areas of research inquiry to pursue. Ultimately, we aim to translate diagrams into computational models for in silico intervention and policy analyses.

Conclusions

Community health partnerships tackle many “messy” problems that involve significant racial inequities. To address the issue of violence and racism,43 we used CRT to adapt GMB. Our process and similar adaptations could be applied to other health issues (e.g., vignettes could be created about people’s lived experiences around obesity or mental health).21 Engaging with community collaborators to adapt methods can improve cultural relevance. Appropriate methods can produce trans-disciplinary insights to avoid “Band-Aid” solutions and generate quality scholarship.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM108337 and T32 MH020061) and the University of Rochester Office of the President. The Susan B. Anthony Center provided funding for Dr. Cerulli’s contribution.

Appendix A. Group Model Building Script

| Problem Framing With a Vignette | |

|

| |

| Context: | At the beginning of a group model building process |

| Purpose: | Engage with stakeholders in a manner that resonates and is relatable to them and their community in order to frame the problem and initiate mapping |

| Status: | New |

| Primary nature of group task: | Convergent |

| Preparation time: | 3–4 hours |

| Time required during session: | 45 minutes |

| Follow-up Time: | 0 minutes |

| Materials needed: | Worksheet A Blank paper Tacks or tape Markers Adhesive dots or electronic voting mechanism |

| Inputs: | Vignette about the topic (e.g., short essays that present an unidentifiable/fictionalized story that presents the topic of focus at a personal or community level) |

| Outputs: | Prioritized problem statements (i.e., potential lists of variables to start a causal loop diagram from) |

| Roles: | Facilitator works with group Wall builder to take people’s statements, hang on wall and help group |

|

| |

| Steps | |

|

| |

| The facilitator presents a vignette and allows the participants time to read and digest the story | |

| Based on the vignette, the facilitator instructs the participants to complete as many answers to the following statement on worksheet A: | |

| What stood out to me most about this vignette was that ________________ led to ____________________, | |

| After the participants have time to write their answers, the facilitator asks them to identify their top 1-2 choices of their answers they feel are most important to address | |

| In a round-robin fashion, each participants reads aloud their top statement | |

| The facilitator writes each statement on flip chart paper that is on a wall. | |

| After the group has gone through once identifying and posts it on the wall, the facilitator asks participants to provide their second top statement if it has not already been provided. | |

| The facilitator tries to identify any themes and groupings among the statements and/or asked the participants to help quickly identify the top 8 items from those on the list. | |

| After a reduced list is confirmed, participants are allowed to vote for their top choice (either | |

Appendix B. “The Player” Orientation Materials

Causal Loop Diagramming

We live in a complex world, full of relationships between people and things that change over time and influence each other in unexpected ways.

“Causal Loop Diagramming” is a way to sort out these complex relationships and better understand how and why things occur.

The following introduces a few basics of Causal Loop Diagramming by using a generic but familiar storyline that serves as the basis for many movies and tv shows.

“The Player”

There are multiple versions and twists to this storyline, but in its basic form it’s typically about an attractive wealthy man. This man thinks he is God’s gift to women. He dates multiple women, using manipulation and seductive behavior. However, at some point he ends up getting a bit too ‘cocky’ and is unable to hide his deceit and the multiple ‘girlfriends’ find out about each other. Often this is when he ‘girlfriends’ get together and seek revenge.

Let’s walk through this example using causal loop diagramming to visualize this storyline.

Variables and Arrows

We start with “variables” that can go up or down and arrows that connect them.

The man’s ‘money and attractiveness’ increases his ‘arrogance and conceit’

His ‘arrogance and conceit’ increases his use of manipulation and seductive behaviors.

We label the arrows with “S’s” because the variables are moving in the same direction.

S’s = move in same direction

Feedback Loop (Reinforcing)

Continuing the story, as his arrogance and conceit increases, so does his use of manipulation and seduction, he gains more girlfriends, which feeds back to increase his arrogance.

These circular paths create what we call reinforcing loops. This is because we started with an increase in arrogance and conceit and came back around to again increase arrogance and conceit.

Also important, we find that as the number of girlfriends increase, the less time he has to spend with each of them.

We label this arrow with an O, because the variables are moving in opposite directions.

The less time to spend with each girlfriend, the less able he can keep the girlfriends all happy.

O’s = opposite direction.

Feedback Loop (Balancing)

Continuing along this path, the less he can keep his girlfriends happy, the more the girlfriends break up with him, which feeds back to reduce his number of girlfriends.

These circular paths create what we call balancing loops. This is because we started with an increase in girlfriends, and came back around to decrease his number of girlfriends.

A simple rule for determining if a loop is reinforcing or balancing is to count the number of “O’s”. Zero or even number of O’s = reinforcing loop.

An odd number of O’s = balancing loop.

Next, let’s think about how the number of girlfriends impacts his free time.

As his number of girlfriends increases, the amount of free time taken up by the girlfriends increases (S), this reduces the time he has to make sure the girlfriends don’t meet each other (O). The less time he spends to ensure they don’t meet each other will then increase the chance that the girlfriends find out about each other (O). Finally, the more the girlfriends find out about each other, the less he is keeping them happy (O).

Once again we have a balancing loop.

Delays

Sometimes there are delays between two variables – something may change and impact another variable some time passes – information doesn’t flow immediately – and allows for other pieces of the story to unfold.

For example, the girlfriends may find out about each other, but they don’t make this immediately known to our ‘player’ and so there is some time before he realizes that they know about each other.

This delay is labeled with two hash marks on the arrow.

Meanwhile, as the girlfriends find out about each other, they are going to increase their plans to seek revenge (S).

As the player gains information that the girlfriends know about each other, he can increase his ability to take corrective action (S), which then may reduce the girlfriends ability to take revenge (O). But remember, the delay in the system.

Overshoot and Collapse

As the girlfriends seek revenge, a likely target is to go after and try to reduce his money and attractiveness (O).

Finally, with the decrease in money and attractiveness, comes a reduction in arrogance in conceit (S).

Appendix C. Locally Developed “Gracious Space”

Gracious Space

To create and maintain an environment in which honesty, equity, reciprocity, and partnership can thrive; the group enters into an agreement on honoring “Gracious Space”. The difference between gracious space and ground rules are that “rules” are things and often are set by others, have punitive consequences, and have a restraining connotation. Gracious Space is all about honor and respect for the place, time and people involved in a particular conversation. It allows for safe space in which to engage in real meaningful thought and conversation. Each group creates their own agreement. Start with a few on the board and have the group quickly add anything that is important to them or that is missing. Challenge anything that they disagree with or question. Below is an example of things to start with.

Start with:

Step up, Step Back – (both share and listen – everyone participates but no one dominates)

Keep it Real (be honest)

Respect one another and disagree without being disagreeable (disagreement is inevitable and encouraged for our learning, however to allow for real growth, we must express ourselves, as well we are able, in ways that people can ‘hear’ us, without shutting each other down and trusting that people are beginning from a sincere place of wanting to learn and be heard.)

Speaking Order (one person speaks at a time, guided by facilitators who will keep track of who wants to speak in order as well as they are able)

Use of ‘Ouch’ (when some feels offended by something another person has said, one can acknowledge the hurt by saying ‘ouch.’ The facilitator will recognize the ‘ouch’ to the degree that the individual and the group feel it needs attention before moving on – as much as possible, without derailing the focus of the group unless absolutely necessary at that moment.)

Be responsible for our own defensiveness and learning (Check our defensiveness and be responsible for our own learning.)

Take a breath before responding to a moment when we feel accused or misunderstood. Rather than immediate response, use the speaking order to allow any response, if necessary, to be thoughtful and reflective.

Do not place responsibility on others for learning that we need to work on ourselves and accept that some learning we may have to do outside of the circle in order to allow the group to move forward.

Turn off technology (or put on vibrate) – if necessary please leave room to answer.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine Community. The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 178–211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkins N, Tsao B, Hertiz M, et al. Connecting the dots: An overview of the links among multiple forms of violence. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.James SE, Johnson J, Raghavan C, et al. The violent matrix: A study of structural, interpersonal, and intrapersonal violence among a sample of poor women. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31(1–2):129–41. doi: 10.1023/a:1023082822323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders-Phillips K. Racial discrimination: A continuum of violence exposure for children of color. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2009;12(2):174–95. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVerteuil G. Conceptualizing violence for health and medical geography. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. Am Behav Sci. 2013;57(8) doi: 10.1177/0002764213487340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloomberg MR, Webster DW, Vernick JS. Reducing gun violence in America:Informing policy with evidence and analysis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamby S. The second wave of violence scholarship: Integrating and broadening theories of violence. Psychol Violence. 2011;1(3):163–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The effectiveness of nominal, delphi, and interacting group decision making processes. Acad Manage J. 1974;17(4):605–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane M, Trochim WM. Concept mapping for planning and evaluation. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vennix JA. Group model‐building: tackling messy problems. System Dynamics Review. 1999;15(4):379–401. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen DF, Richardson GP, Vennix JA. Group model building: adding more science to the craft. System Dynamics Review. 1997;13(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersena D, Richardsona G. Scripts for group model building. System Dynamics Review. 1997;13(2):107–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richardson GP, Andersen DF. Teamwork in group model building. System Dynamics Review. 1995;11(2):113–37. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen DF, Vennix JA, Richardson GP, et al. Group model building: problem structuring, policy simulation and decision support. J Oper Res Soc. 2007:691–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sterman JD. Causal loop diagrams Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2000. pp. 135–90. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulmer JT, Harris CT, Steffensmeier D. Racial and ethnic disparities in structural disadvantage and crime: White, Black, and Hispanic comparisons. Social Science Quarterly. 2012;93(3):799–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norton MI, Sommers SR, Apfelbaum EP, et al. Color blindness and interracial interaction playing the political correctness game. Psychol Sci. 2006;17(11):949–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham L, Brown-Jeffy S, Aronson R, et al. Critical race theory as theoretical framework and analysis tool for population health research. Critical Public Health. 2011;21(1):81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yosso TJ. Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education. 2005;8(1):69–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crenshaw K. Critical race theory:The key writings that formed the movement. New York: The New Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.BeLue R, Carmack C, Myers KR, et al. Systems thinking tools as applied to community-based participatory research a case study. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39(6):745–51. doi: 10.1177/1090198111430708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bridgewater K, Peterson S, McDevitt J, et al. A community-based systems learning approach to understanding youth violence in Boston. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5(1):67–75. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassmiller Lich K, Minyard M, Niles R, Dave G, et al. System dynamics and community health. In: Burke J, Albert S, editors. Methods for Community Public Health Research. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 129–70. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Homer JB, Hirsch GB. System dynamics modeling for public health: background and opportunities. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):452–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.062059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Census Bureau. State and County QuickFacts. [cited 2015 January 28]. Available from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/36/3663000.html.

- 29.Doherty EJ, Rochester A. Poverty and the Concentration of Poverty in the Nine-county Greater Rochester Area: December 2013. Rochester: Rochester Area Community Foundation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.ACT Rochester. Community indicators for the Greater Rochester area: Center for Governmental Research. 2015 [cited 2015 January 27]. Available from: http://www.actrochester.org.

- 31.Hare M. Riots still haunt Rochester. Rochester City Newspaper. 2014 Jul 16; Sect. News and Opinion. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh A, Lagebacher M, Duda J, et al. The geography of crime in Rochester: Patterns over time (2005-2011) Rochester, NY: Center for Public Safety Initiatives; 2012. Contract No.: 2012-10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.White AM, Funchess M, Sellers C, et al. Recruitment and training of natural helpers as action-research partners: Developing ecosystems of mental health promotion and violence prevention in the urban neighborhood. Sixth World Conference on the Promotion of Mental Health and Prevention of Mental and Behavioral Disorders; Washington (DC). 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 34.White AM, Lu N, Cerulli C, Tu X. Examining benefits of academic–community research team training: Rochester’s suicide prevention training institutes. Progr Community Health Partnersh. 2014;8(1):125–37. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2014.0000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hovmand P, Rouwette E, Andersen D, et al., editors. Scriptapedia: A Handbook of Scripts for Developing Structured Group Model Building Sessions; International System Dynamics Conference; Washington (DC). 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luna‐Reyes LF, Martinez‐Moyano IJ, Pardo TA, et al. Anatomy of a group model‐building intervention: Building dynamic theory from case study research. System Dynamics Review. 2006;22(4):291–320. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackermann F, Andersen DF, Eden C, et al. ScriptsMap: A tool for designing multi-method policy-making workshops. Omega. 2011;39(4):427–34. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rouwette EA, Vennix JA, Mullekom Tv. Group model building effectiveness: a review of assessment studies. System Dynamics Review. 2002;18(1):5–45. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas SB, Quinn SC, Butler J, et al. Toward a fourth generation of disparities research to achieve health equity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:399–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Center for Ethical Leadership. Gracious Space Seattle. [cited 2015 Jan 28 ]. Available from: http://www.ethicalleadership.org/gracious-space.html.

- 41.Aiyer SM, Zimmerman MA, Morrel-Samuels S, et al. From broken windows to busy streets a community empowerment perspective. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42(2):137–47. doi: 10.1177/1090198114558590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Light MT, Harris CT. Race, space, and violence: Exploring spatial dependence in structural covariates of white and black violent crime in US counties. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2012;28(4):559–86. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander M. The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The New Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]