Abstract

Heterozygous mutation of the transcription factor HNF1B is the most common cause of monogenetic developmental renal disease. Disease-associated mutations fall into two categories: HNF1B intragenic mutations and a 1.3 Mb deletion at chromosome 17q12. An increase in neurodevelopmental disorders has been observed in individuals harbouring the 17q12 deletion but not in patients with HNF1B coding mutations.

Previous investigations have concentrated on identifying a genetic cause for the increase in behavioural problems seen in 17q12 deletion carriers. We have taken the alternative approach of investigating the DNA methylation profile of these two HNF1B genotype groups along with controls matched for age, gender and diabetes status using the Illumina 450K DNA methylation array (total sample n = 60).

We identified a number of differentially methylated probes (DMPs) that were associated with HNF1B-associated disease and passed our stringent experiment-wide significance threshold. These associations were largely driven by the deletion patients and the majority of the significant probes mapped to the 17q12 deletion locus. The observed changes in DNA methylation at this locus were not randomly dispersed and occurred in clusters, suggesting a regulatory mechanism reacting to haploinsufficiency across the entire deleted region.

Along with these deletion-specific changes in DNA methylation, we also identified a shared DNA methylation signature in both mutation and deletion patient groups indicating that haploinsufficiency of HNF1B impacts on the methylome of a number of genes, giving further insight to the role of HNF1B.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13148-018-0530-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Epigenetics, DNA methylation, HNF1B, CNV, 17q12 deletion, Renal disease, Autism

Introduction

The most common monogenic cause of developmental kidney disease is heterozygous mutation of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (HNF1B) gene, located at chromosome 17q12 [1–3]. This gene encodes a transcription factor with important roles in the development of the kidney, pancreas, genital tract and liver [4]. Renal cysts are the most frequently observed clinical feature in HNF1B-associated renal disease, although the phenotype is very variable despite the single genetic aetiology [5]. Abnormalities are often detected on prenatal ultrasonography, where bilateral hyperechogenic kidneys with normal or slightly increased size are commonly found [6]. The prevalence of HNF1B-associated renal disease depends on which study cohort is selected; the detection rate ranges from 5% in children ≤ 16 years with renal aplasia/hypoplasia and chronic kidney disease to 31% in children with renal cysts, hyperechogenicity, hypoplasia or a single kidney [2, 7].

Extra-renal phenotypes are also common and include early-onset diabetes mellitus, pancreatic hypoplasia, genital tract malformations and abnormal liver function tests [8–13]. The mean age at diagnosis of diabetes is 24 years but can vary from the neonatal period to late middle age [14]. The pathophysiology reflects a combination of β cell dysfunction and insulin resistance; dysfunction of β cells results in reduced insulin secretion and is likely to be a consequence of pancreatic hypoplasia [10]. Most patients require treatment with insulin [14].

Heterozygous mutations in HNF1B generally occur in two forms; approximately 50% of patients are affected by an intragenic mutation (base substitution or small insertion/deletion within the HNF1B gene) with the other common mutation being a ~ 1.3 Mb deletion at chromosome 17q12, which encompasses the entire HNF1B gene [15, 16]. This region of chromosome 17 is susceptible to genomic rearrangement, which is mediated by non-allelic homologous recombination between flanking segmental duplications [17]. Interestingly, the recurrent 17q12 deletion has also been associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [18, 19]. The 1.3 Mb deleted region contains 14 genes in addition to HNF1B, and it is not currently clear what genetic mechanism gives rise to this neurodevelopmental comorbidity. Until recently, there was no evidence to suggest a genotype-phenotype correlation for any of the other clinical features seen in HNF1B-associated disease; this is consistent with haploinsufficiency as the underlying disease mechanism [15, 16]. However, recent work by Dubois-Laforgue and colleagues has shown renal function may be worse in patients with an HNF1B intragenic mutation than in those with a deletion [20].

Expression of the phenotype can vary significantly between families carrying the same HNF1B mutation and even between affected members of the same family, which suggests that additional genetic and/or environmental modifiers might influence the HNF1B phenotype. Most efforts to understand this phenotypic variation have concentrated on studying changes in the DNA sequence. To date, epigenetic mechanisms which act to developmentally regulate gene expression via modifications to DNA, histone proteins and chromatin have not been explored. DNA methylation is the most well characterised and stable epigenetic modification, influencing gene expression via the disruption of transcription factor binding and the attraction of methyl-binding proteins that initiate chromatin compaction and gene silencing. DNA methylation can be directly affected by DNA sequence variation—including large structural variants—both locally (in cis) and at more distal locations in the genome (in trans) [21–24]. In this study, we set out to characterise the epigenetic signature of HNF1B-associated disease and to determine if the signature differs depending on mutation classification: we profiled genome-wide patterns of DNA methylation in 20 individuals with an HNF1B intragenic mutation (HNF1Bmtn), 20 individuals with a 17q12 deletion encompassing HNF1B (17q12del) and 20 controls (ctrl) matched for age, gender and diabetes status.

Methods

Sample description

DNA was isolated from whole blood collected from unrelated individuals with HNF1B-associated disease who had been referred for genetic testing to Exeter Molecular Genetics Laboratory from 1998 to 2012; the criterion for initial referral was suspicion of HNF1B-associated disease by the referring clinician. DNA was isolated using standard phenol:chloroform methods and checked for quality and purity. Informed consent was obtained to perform HNF1B genetic testing as part of their clinical care, and the study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles. Mutation screening was performed by sequencing of coding exons and exon-intron boundaries together with gene dosage assessment by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) as previously described [16, 25]. Control DNA was collected from two sources: (i) for individuals without diabetes mellitus, controls were individuals referred to Exeter Molecular Genetics Laboratory as above but with no HNF1B gene mutation or deletion detected on genetic testing; (ii) for individuals with diabetes mellitus, controls were individuals from the UNITED (Using pharmacogeNetics to Improve Treatment in Early-onset Diabetes) study with presumed type 1 diabetes mellitus based on a urine C-peptide/creatinine ratio ≥ 0.2 nmol/mmol with positive islet autoantibodies [26]. All individuals had a serum creatinine level < 250 μmol/L and were matched for age, sex and presence of diabetes (Table 1). All samples included in the study were unrelated. Two patients in the 17q12 deletion group had known neurodevelopmental disease (a 10-year-old female with developmental delay and a 31-year-old male with Asperger’s syndrome).

Table 1.

Sample demographic table

|

HNF1B intragenic mutation (n = 21) |

17q12 deletion (n = 21) |

Control* (n = 21) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (interquartile range) | 10 (2–28) | 9 (2–31) | 9 (2–29) |

| Sex, n (%) | Male 8 (38) | Male 8 (38) | Male 8 (38) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 9 (43) | 9 (43) | 9 (43) |

| Renal abnormality, n (%) | |||

| -Renal cysts/cystic dysplasia | 12 (57) | 12 (57) | 8 (38) |

| -Renal hyperechogenicity | 2 (10) | 1 (5) | 2 (10) |

| -Single kidney | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| -Multicystic and dysplastic kidney | 2 (10) | 2 (10) | 1 (5) |

| -Obstruction | – | 2 (10) | – |

The samples were matched for age, sex and diabetes status; all individuals had a serum creatinine level < 250 μmol/L

*For individuals without diabetes mellitus, controls were individuals with no HNF1B gene mutation or deletion detected on genetic testing; for individuals with diabetes mellitus, controls were individuals from the UNITED (Using pharmacogeNetics to Improve Treatment in Early-onset Diabetes) study with presumed type 1 diabetes

Methylomic profiling

Blood-derived DNA was profiled using the HumanMethylation450 BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) and scanned on an Illumina HiScan System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Illumina Genome Studio software was used to extract the raw signal intensities of each probe (without background correction or normalisation). Signal intensities for each probe were imported into R [27] using the methylumi and minfi packages [28, 29]. Multidimensional scaling plots of sex chromosome probes were used to check that the predicted sex corresponded with the reported sex for each individual. The 65 SNP probes, cross-hybridising probes [30, 31] and probes containing a SNP 10 bp from the extension position (MAF > 0.05) were excluded from analysis [30]. The ‘pfilter’ function of the wateRmelon package [32] was used to filter data by beadcount and detection P value. Samples with > 1% probes with a detection Pvalue > 0.01 were removed, along with probes with a detection P value > 0.05 in at least 1% of samples and/or a beadcount < 3 in 5% of samples were also removed. The ‘dasen’ function in wateRmelon was used to normalise the data as previously described [32]. The number of samples that passed quality control was 60 (HNF1B intragenic mutation (n = 20), 17q12 deletion (n = 20) and control (n = 20) and a total of 388,295 CpG sites were included in the final dataset.

Bisulfite pyrosequencing

A selected region was chosen to verify the array findings using the complementary technology of bisulfite pyrosequencing using the Qiagen Q24 Pyrosequencer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) (see [33]). Primers, probes and the PCR conditions for the selected region can be found in Additional file 1: Table S1; the sequencing reaction was performed using the manufacturer’s protocol.

Statistical analysis

Differentially methylated position (DMP)

The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to test for differentially methylated sites associated with one of the three groups: HNF1B intragenic mutation (n = 20), 17q12 deletion (n = 20) or control (n = 20). DNA methylation values for each probe were regressed against HNF1B status with covariates for age, gender, diabetes status and cellular composition. As cell count data were not available for these DNA samples these were estimated from the DNA methylation data using both the Epigenetic Clock software [34] and the Houseman algorithm [35, 36]. To determine which group was driving the association behind the significant ANOVA results, the T statistics for controls versus each of the two HNF1B distinct genetic groups were extracted from the regression model. The presence of the 17q12 deletion was confirmed by analysing the DNA methylation raw data using the function ‘champ.CNA’ from the package ChAMP [37].

Differentially methylated regions (DMRs)

The P values for the comparisons between the control group and HNF1B genotype status from the regression analysis were converted into BED files and run through the comb-p [38] pipeline with a seed of (5 × 10−4) and distance parameter set to 500 bp. Briefly, comb-p generates DMRs by (1) calculating the auto-correlation between probes to adjust the input DMP P values using the Stouffer-Liptak-Kechris correction, (2) running a peak finding algorithm over these adjusted P values to identify enriched regions around a seed signal, 3) calculating region P value using the Stouffer-Liptak correction and (4) correcting for multiple testing with the one-step Šidák correction. Significant regions were identified as those with at least two probes and corrected P value < 0.05.

Results

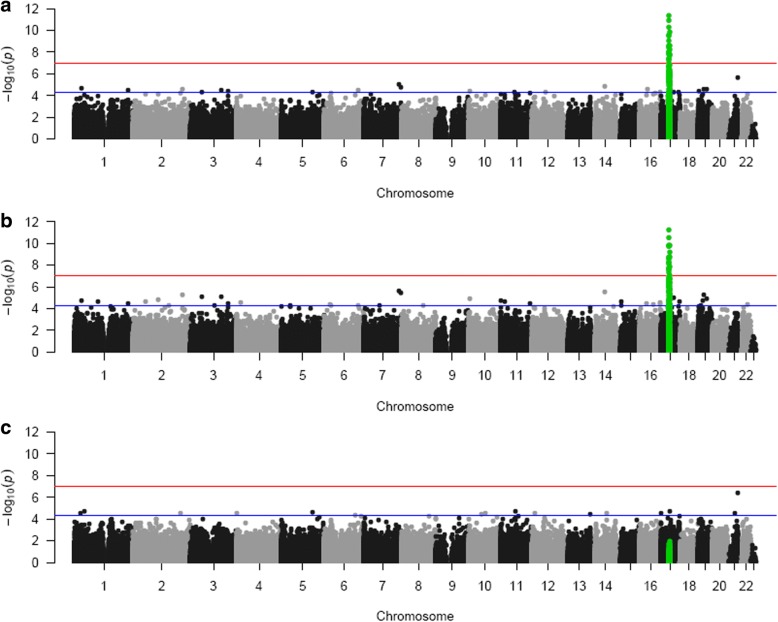

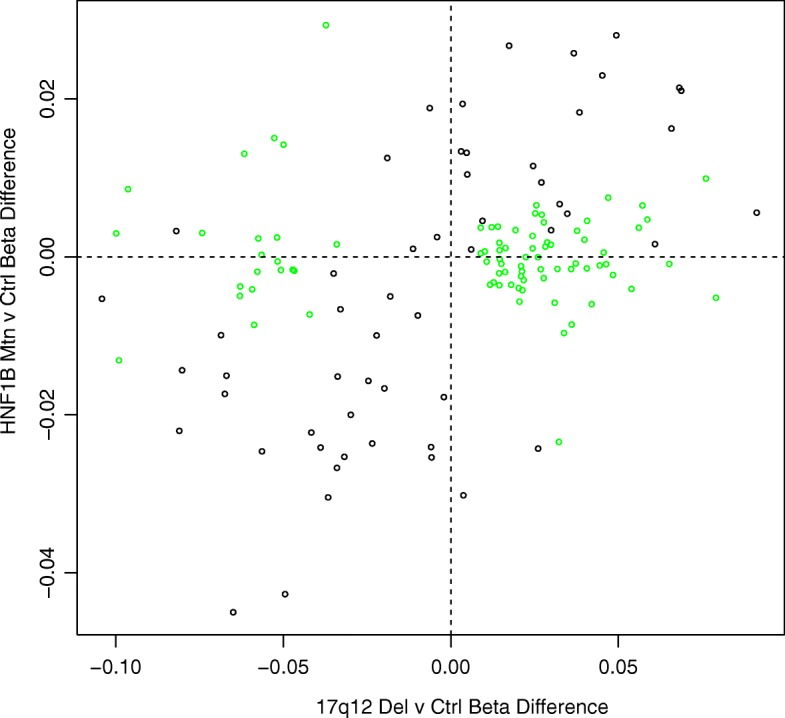

All samples characterised as 17q12 deletion carriers were confirmed by the CNV calling function in CHAMP which uses the intensity data from the DNA methylation array (see Additional file 2: Figure S1). The probe-wise ANOVA analysis on the three groups (HNF1B intragenic mutation, 17q12 deletion and control) identified 21 differentially methylated positions (DMPs) (see Table 2) that passed our experiment-wide significance threshold (P < 1 × 10−7), representing a 5% family-wise error-rate estimated from 5000 permutations (see [39]), with 94 additional DMPs reaching a more relaxed ‘discovery’ threshold of P < 5 × 10−5 (Additional file 3: Table S2). To determine which group was driving this association, we extracted the P values for the T statistics from the model HNF1B intragenic mutation vs control and 17q12 deletion vs control; these results clearly show that the 17q12 deletion group is driving most of the associations seen in the ANOVA (see Table 2). All of the significant DMPs (P < 1 × 10−7) are located in the 17q12 deletion region (see Figs. 1 and 2) suggesting that the deletion is exerting effects in cis. While this region appears to be driving the main associations observed, probes situated outside the deletion region, which are associated with both HNF1B genotype groups, are strongly correlated (r = 0.63, P = 2.626E−07); see Fig. 3 and Additional file 4: Table S3 for a list of probes that are significantly differently methylated in both HNF1B genotype groups compared to controls.

Table 2.

Top results from the probe-wise ANOVA analysis. The T statistic results from the regression analysis indicate that the association is mainly driven by the 17q12 deletion patients. DMP results are annotated with their genomic location and gene annotation taken from the annotation files provided by Illumina. (*The coefficient value is equivalent to the magnitude of change in DNA methylation beta value and the direction of effect is in comparison to the control group)

| Illumina Probe ID | F statistic | ANOVA P value | ANOVA q values | CHR | MAPINFO (hg19) | Gene name | ctrl v 17q12del | ctrl vs HNF1B mtn | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T statistic | Coefficient* | P value | T statistic | Coefficient* | P value | |||||||

| cg06475972 | 47.017 | 4.00E-12 | 1.55E−06 | 17 | 34842357 | ZNHIT3 | 9.045 | 0.043 | 5.06E−12 | 0.074 | 0.000 | 0.942 |

| cg17953633 | 43.696 | 1.28E−11 | 2.49E−06 | 17 | 34957751 | MRM1 | 8.532 | 0.069 | 2.97E−11 | −0.417 | − 0.003 | 0.678 |

| cg24685795 | 40.277 | 4.52E−11 | 5.84E−06 | 17 | 34851276 | ZNHIT3 | − 8.075 | − 0.107 | 1.47E−10 | 0.674 | 0.008 | 0.504 |

| cg18269801 | 37.212 | 1.48E−10 | 1.44E−05 | 17 | 35732756 | ACACA | − 8.088 | − 0.061 | 1.40E−10 | − 0.184 | − 0.001 | 0.855 |

| cg05527869 | 35.891 | 2.52E−10 | 1.95E−05 | 17 | 35294476 | LHX1 | 7.988 | 0.025 | 1.99E−10 | 0.310 | 0.001 | 0.758 |

| cg04264908 | 35.376 | 3.10E−10 | 2.01E−05 | 17 | 35303330 | 8.057 | 0.060 | 1.56E−10 | 0.716 | 0.005 | 0.477 | |

| cg22359664 | 32.781 | 9.19E−10 | 5.10E−05 | 17 | 35289432 | 7.094 | 0.044 | 4.75E−09 | − 1.023 | − 0.006 | 0.311 | |

| cg07037057 | 30.723 | 2.25E−09 | 0.000107005 | 17 | 35969138 | SYNRG | 7.684 | 0.076 | 5.84E−10 | 1.382 | 0.012 | 0.173 |

| cg18103097 | 30.332 | 2.68E−09 | 0.000107005 | 17 | 35414317 | − 7.386 | − 0.071 | 1.68E−09 | − 0.415 | − 0.004 | 0.680 | |

| cg20151045 | 30.270 | 2.76E−09 | 0.000107005 | 17 | 35414114 | AATF | − 7.242 | − 0.051 | 2.80E−09 | − 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.986 |

| cg20951949 | 29.512 | 3.88E−09 | 0.000136867 | 17 | 34898162 | − 7.047 | − 0.078 | 5.60E−09 | 0.254 | 0.003 | 0.801 | |

| ch.17.958355F | 28.600 | 5.89E−09 | 0.000190431 | 17 | 35991457 | DDX52 | 7.365 | 0.055 | 1.81E−09 | 1.110 | 0.008 | 0.273 |

| cg19678067 | 27.750 | 8.74E−09 | 0.00026103 | 17 | 34901173 | GGNBP2 | 6.725 | 0.033 | 1.77E−08 | − 0.509 | − 0.002 | 0.613 |

| cg06655187 | 27.194 | 1.14E−08 | 0.000315011 | 17 | 34842929 | ZNHIT3 | 7.335 | 0.018 | 2.01E−09 | 1.984 | 0.004 | 0.053 |

| cg03146993 | 26.915 | 1.30E−08 | 0.000335768 | 17 | 35297146 | LHX1 | 6.987 | 0.041 | 6.95E−09 | 0.487 | 0.003 | 0.628 |

| cg18574725 | 26.761 | 1.40E−08 | 0.000338748 | 17 | 34900600 | GGNBP2 | 6.659 | 0.032 | 2.24E−08 | − 0.370 | − 0.002 | 0.713 |

| cg06397845 | 26.545 | 1.55E−08 | 0.000353603 | 17 | 35732737 | ACACA | − 6.809 | − 0.066 | 1.31E−08 | − 0.092 | − 0.001 | 0.927 |

| cg00356511 | 26.177 | 1.85E−08 | 0.000398715 | 17 | 35716273 | ACACA | 6.279 | 0.024 | 8.68E−08 | − 1.035 | − 0.004 | 0.306 |

| cg02787306 | 25.017 | 3.26E−08 | 0.000665877 | 17 | 34957963 | MRM1 | 6.652 | 0.044 | 2.29E−08 | 0.209 | 0.001 | 0.835 |

| cg27614319 | 24.275 | 4.72E−08 | 0.000916069 | 17 | 35079061 | 6.453 | 0.040 | 4.68E−08 | − 0.073 | 0.000 | 0.942 | |

| cg04993975 | 24.159 | 5.00E−08 | 0.000924571 | 17 | 35294472 | LHX1 | 6.648 | 0.024 | 2.33E−08 | 0.555 | 0.002 | 0.582 |

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plots of the three analyses. a P values from the ANOVA test on the three genotype groups (HNF1B intergenic mutation, 17q12 deletion and controls). Highlighted in green are the 450K probes that are located in the 17q12 deletion region. b P values from the T statistic from the regression model on controls compared to the 17q12 deletion samples. c P values from the T statistic from the regression model on controls compared to the HNF1B mutation samples. (The red line indicates experiment-wide significance threshold (P < 1 × 10−7), and the blue line is a more relaxed ‘discovery’ threshold of P < 5 × 10–5)

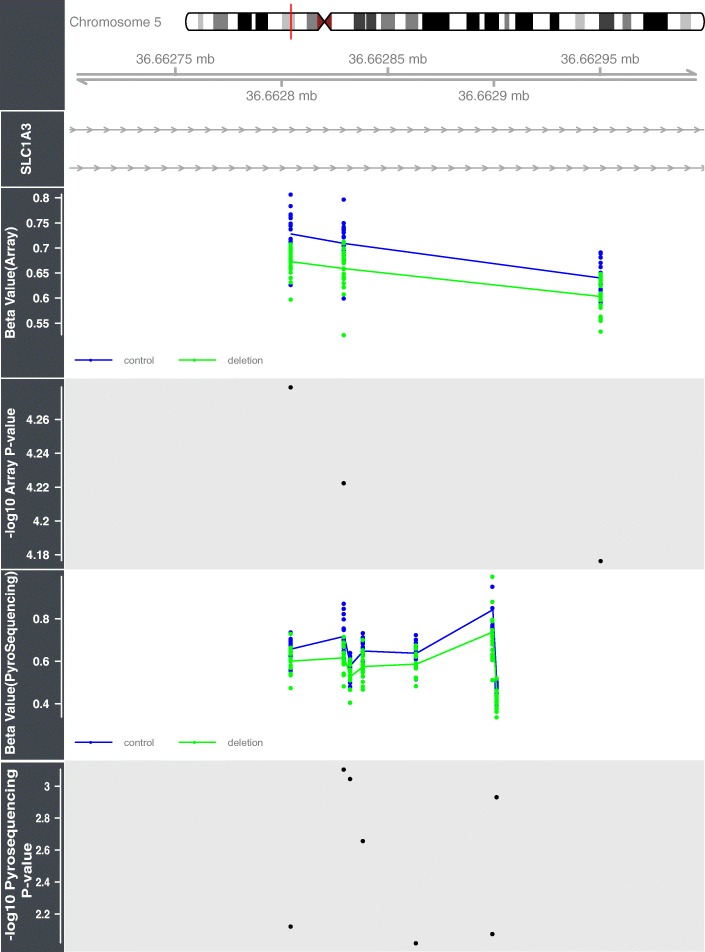

Fig. 2.

This figure illustrates the 17q12 deletion locus with the identified DMRs highlighted across the region. The regression coefficient and P values from the analysis comparing the 17q12 deletion subject with controls illustrates that both hyper and hypo DNA methylation changes are associated with the deletion

Fig. 3.

This scatterplot demonstrates the concordance in effect size between the two HNF1B genetic groups compared to controls when probes in the 17q12 deletion region (coloured green) are discounted

DMR analysis comparing controls with the 17q12 deletion group identified a number of regions that were significant after correction for multiple comparisons using the comb-p program (Table 3). The majority of the DMRs identified were located in the 17q12 deletion region (Fig. 2). However, there were a few regions outside the deletion region that exhibited significant differential methylation; of interest were changes in the gene SLC1A3 (corrected P = 4.71E−07, mean DNA methylation beta value Δ − 0.06), which has previously been implicated in Autism [40]. The DMR located in intron 3 of this gene was selected for verification with pyrosequencing. The assay designed only covered two of the three original probes comprising the DMR but did include an additional five CpG sites that were not present on the 450K array. The pyrosequencing data was converted into beta values (by dividing the pyrosequencing % values by 100) and regressed against HNF1B status with covariates for age, diabetes status, gender and cell composition as in the initial analysis. The five additional sites assayed by the pyrosequencer all showed significant hypomethylation (P < 0.01) in the 17q12 deletion patients compared to the controls (see Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Differential methylation regional (DMR) analysis on the two HNF1B deficient groups of patients compared to the controls (highlighted in blue is the DMR residing in the gene SLC1A3 which was validated using pyrosequencing)

Fig. 4.

This figure shows the validation of the DMR located in the gene SLC1A3 with bisulfite pyrosequencing. All CpGs assayed, including those not present on the 450K array, show significant hypomethylation in subjects harbouring a 17q12 deletion

In contrast, only one significant DMR was located in the analysis comparing controls with the HNF1B mutation group (see Table 3).

Discussion

In this study, we have assessed genome-wide patterns of DNA methylation in DNA derived from the blood of individuals with HNF1B-associated disease along with matched healthy controls. The aim of this experiment was to determine if there was an epigenetic signature that can distinguish HNF1B intragenic mutation patients from those with a 17q12 deletion. While both genotype groups result in developmental kidney disease only individuals with the 17q12 deletion appear to have a greater risk of developing neuropsychiatric symptoms, suggesting the contribution of other genes or regulatory mechanisms are at play.

We first examined site-specific genome-wide patterns of DNA methylation in the three groups studied (HNF1B mutations, 17q12 deletion and controls) and found striking changes in DNA methylation of the 17q12 deletion region. The 21 DMPs that reached our experimental-wide significance threshold all mapped to the 17q12 deletion region. While we do see a drop in signal intensity in this region in the deletion samples, it is consistent across the methylated and unmethylated channels so will not influence the calculated beta values. Interestingly, the direction of effect is not consistent, with probes exhibiting both gains and losses of DNA methylation suggesting the observed changes are not a technical artefact on the array resulting from the haploinsufficiency of the region. Comparing the two HNF1B genotype groups with controls separately confirmed that the association located to the 1.3 Mb deletion at chromosome 17q12 was driven by the 17q12 deletion samples.

Given that DNA methylation at adjacent probes is often correlated, we employed regional-based analysis and identified 20 DMRs in the 17q12 deletion samples, 13 of which were located in the 1.3 Mb deletion region. The most significant DMR mapped upstream of the gene LHX1 (corrected P = 3.37E−18, mean DNA methylation beta Δ + 0.02) (see Additional file 5: Figure S2), which is known to play a role in brain development and function [41, 42] as well as being directly regulated by HNF1B during kidney development [43, 44].

These observations suggest a possible compensatory mechanism mediated by DNA methylation reacting to haploinsufficiency in the vicinity of the deletion. The enrichment of DMRs in this region indicates that this phenomenon is not entirely random and highlights a number of loci in the region that may have regulatory importance. Recently, DNA methylation has been found to have a major role in “fine-tuning” the expression of genes located in CNVs found in various different cancers [45].

While there is a substantial enrichment of DMRs in the deletion region a number of DMRs were identified elsewhere in the genome, one of which was located in the gene SLC1A3 on chromosome 5. Genetic variations in this gene have been linked to autism and expression changes in this gene have been identified in schizophrenia patients; both these disorders have been associated with the 17q12 deletion [18, 46]. Further work is needed to identify whether alterations in the DNA methylation profile in this gene affect gene function.

So far, we have concentrated on the differences in the DNA methylation signature in the 17q12 deletion subjects which are not shared by the HNF1B mutation subjects. However, these two groups have similar phenotypes and this was reflected in the DNA methylation profile of the two groups once the probes located in the 17q12 region are removed, indicating that there is a shared network of genes that are dysregulated due to the haploinsufficency of HNF1B (see Fig. 3 and Additional file 4: Table S3). The majority of these shared probes are significantly hypomethylated in both patient groups compared to controls and include cg01445838 (17q12del vs control P = 5.38E−05, coefficient = − 0.064, HNF1B mutation vs control P = 0.000213, coefficient = − 0.052), which is located in the maternally imprinted gene PLAGL1. This gene is known to be involved in fetal growth and is necessary for normal pancreatic islet development [47]. Furthermore, loss of DNA methylation at this locus results in transient neonatal diabetes mellitus which is postulated to be caused by an increase in expression of PLAGL1 [48].

The main limitation of this study is that it uses blood-derived DNA and not disease-relevant tissue and/or cells (e.g. the kidney or the brain). However, genetic-mediated changes in DNA methylation (methylation QTLS) have been found to be considerably stable across different tissues and cell types [39] suggesting that we may be able to extrapolate these findings to other more relevant tissues.

Clinical details were taken from information available at the time of referral for genetic testing; there may be patient factors present, including medication history, which we have been unable to control for and may have influenced our results. Further, we also do not have detailed psychiatric data available for the samples included in this study so we cannot make any assumptions regarding the DNA methylation status of the 17q12 deletion and the increased prevalence of psychiatric symptoms. Many of the individuals were too young to be assessed for schooling difficulties and the features of neurodevelopmental disease often do not become apparent until children are older.

Conclusion

We have identified significant DNA methylation alterations in individuals with a 17q12 heterozygous deletion, which localise to a 1.3 Mb deletion region. The observed changes in DNA methylation at this locus are not randomly dispersed and occur in clusters suggesting a regulatory mechanism reacting to haploinsufficiency across the deleted region. Along with these deletion-specific changes in DNA methylation, we also identified a common DNA methylation signature in both genotype groups, indicating that haploinsufficiency of HNF1B impacts on the methylome of a number of genes. Further work should investigate the role of these genes in the manifestation of the various phenotypes associated with deficiency of HNF1B and investigate gene expression changes associated with DNA methylation status across the deletion region in disease relevant tissues. Also the increased prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in patients with the 17q12 deletion should be considered and whether alterations in DNA methylation in this region differ depending on psychiatric diagnosis.

Due to the rare nature of HNF1B mutations/deletions, validation of these findings in an independent population was not possible in this study but further work should investigate DNA methylation changes in cis of other more common disease associated copy number variations.

To conclude, we have identified several genes that are differentially methylated in HNF1B-associated disease, some of which are specific to 17q12 deletion subjects. Further, this study is, as far as we are aware, the first to document organised changes in DNA methylation across a large deletion region suggestive of a compensational role of this epigenetic modification.

Additional files

Table S1. SLC1A3 bisulfite pyrosequencing assay conditions. (XLSX 11 kb)

Figure S1. This figure illustrates the extent of the 17q12 deletion in each patient as estimated by the CNV calling algorithm within the CHAMP package. (PDF 15 kb)

Table S2. All anlaysed probes from the ANOVA test with a p-value <0.01. (XLSX 688 kb)

Table S3. Probes that are significantly differentaly methylated in both of the separate group analyses (note that all probes are in the same direction in both analyses). (XLSX 19 kb)

Figure S2. This Figure shows four significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) identified between controls and 17q12 deletion carriers. A) SYNRG (corrected P = 1.32E-17), B) AATF (corrected P = 1.64E-11). C) LHX1 (corrected P = 3.37E-18), D) SMIM24 (corrected P = 1.01E-07). (PDF 223 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

RC is supported by a Medical Research Council Clinical Training Fellowship (grant reference number MR/J011630/1). AH is a core member of the NIHR Exeter Clinical Research Facility and a National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator; he is also supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator award. ED is a recipient of an Academy of Medical Sciences Springboard Award.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- CNV

Copy number variant

- DMP

Differentially methylated position

- DMR

Differentially methylated region

- HNF1B

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

Authors’ contributions

AH, JM, ED and RC conceived the idea for the study. ED and RC collected and analysed the data. BA performed the pyrosequencing. All co-authors contributed to discussions regarding the results. ED and RC wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Use of the Health Research Authority decision tool confirmed that approval by an NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required. Informed consent was obtained from individuals to perform HNF1B genetic testing as part of clinical care, and the study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki Principles.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13148-018-0530-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Rhian L. Clissold, Email: rhian.clissold@nhs.net

Beth Ashfield, Email: beth@themadhouse.info.

Joe Burrage, Email: J.Burrage@exeter.ac.uk.

Eilis Hannon, Email: E.J.Hannon@exeter.ac.uk.

Coralie Bingham, Email: C.Bingham@exeter.ac.uk.

Jonathan Mill, Email: J.Mill@exeter.ac.uk.

Andrew Hattersley, Email: A.T.Hattersley@exeter.ac.uk.

Emma L. Dempster, Email: E.L.Dempster@exeter.ac.uk

References

- 1.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knuppel T, Charbit M, Dusek J, Ghiggeri GM, Jankauskiene A, Mir S, Montini G, Peco-Antic A, et al. Prevalence of mutations in renal developmental genes in children with renal hypodysplasia: results of the ESCAPE study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas R, Sanna-Cherchi S, Warady BA, Furth SL, Kaskel FJ, Gharavi AG. HNF1B and PAX2 mutations are a common cause of renal hypodysplasia in the CKiD cohort. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:897–903. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-1826-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madariaga L, Moriniere V, Jeanpierre C, Bouvier R, Loget P, Martinovic J, Dechelotte P, Leporrier N, Thauvin-Robinet C, Jensen UB, et al. Severe prenatal renal anomalies associated with mutations in HNF1B or PAX2 genes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:1179–1187. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10221012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffinier C, Barra J, Babinet C, Yaniv M. Expression of the vHNF1/HNF1beta homeoprotein gene during mouse organogenesis. Mech Dev. 1999;89:211–213. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(99)00221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heidet L, Decramer S, Pawtowski A, Moriniere V, Bandin F, Knebelmann B, Lebre AS, Faguer S, Guigonis V, Antignac C, Salomon R. Spectrum of HNF1B mutations in a large cohort of patients who harbor renal diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1079–1090. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06810909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Decramer S, Parant O, Beaufils S, Clauin S, Guillou C, Kessler S, Aziza J, Bandin F, Schanstra JP, Bellanne-Chantelot C. Anomalies of the TCF2 gene are the main cause of fetal bilateral hyperechogenic kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:923–933. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006091057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulinski T, Lescure S, Beaufils S, Guigonis V, Decramer S, Morin D, Clauin S, Deschenes G, Bouissou F, Bensman A, Bellanne-Chantelot C. Renal phenotypes related to hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (TCF2) mutations in a pediatric cohort. J Am So Nephrol. 2006;17:497–503. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingham C, Bulman MP, Ellard S, Allen LI, Lipkin GW, Hoff WG, Woolf AS, Rizzoni G, Novelli G, Nicholls AJ, Hattersley AT. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta gene are associated with familial hypoplastic glomerulocystic kidney disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:219–224. doi: 10.1086/316945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Chauveau D, Gautier JF, Dubois-Laforgue D, Clauin S, Beaufils S, Wilhelm JM, Boitard C, Noel LH, Velho G, Timsit J. Clinical spectrum associated with hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:510–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haldorsen IS, Vesterhus M, Raeder H, Jensen DK, Sovik O, Molven A, Njolstad PR. Lack of pancreatic body and tail in HNF1B mutation carriers. Diabet Med. 2008;25:782–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki N, Ogata M, Tomonaga O, Kuroki H, Kasahara T, Yano N, Iwamoto Y. Liver and kidney function in Japanese patients with maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:2144–2148. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montoli A, Colussi G, Massa O, Caccia R, Rizzoni G, Civati G, Barbetti F. Renal cysts and diabetes syndrome linked to mutations of the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene: description of a new family with associated liver involvement. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:397–402. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindner TH, Njolstad PR, Horikawa Y, Bostad L, Bell GI, Sovik O. A novel syndrome of diabetes mellitus, renal dysfunction and genital malformation associated with a partial deletion of the pseudo-POU domain of hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.11.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YZ, Gao Q, Zhao XZ, Bennett CL, Xiong XS, Mei CL, Shi YQ, Chen XM. Systematic review of TCF2 anomalies in renal cysts and diabetes syndrome/maturity onset diabetes of the young type 5. Chin Med J. 2010;123:3326–3333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Clauin S, Chauveau D, Collin P, Daumont M, Douillard C, Dubois-Laforgue D, Dusselier L, Gautier JF, Jadoul M, et al. Large genomic rearrangements in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (TCF2) gene are the most frequent cause of maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5. Diabetes. 2005;54:3126–3132. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.11.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edghill EL, Oram RA, Owens M, Stals KL, Harries LW, Hattersley AT, Ellard S, Bingham C. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta gene deletions—a common cause of renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:627–635. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mefford HC, Clauin S, Sharp AJ, Moller RS, Ullmann R, Kapur R, Pinkel D, Cooper GM, Ventura M, Ropers HH, et al. Recurrent reciprocal genomic rearrangements of 17q12 are associated with renal disease, diabetes, and epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1057–1069. doi: 10.1086/522591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno-De-Luca D, Mulle JG, Kaminsky EB, Sanders SJ, Myers SM, Adam MP, Pakula AT, Eisenhauer NJ, Uhas K, Weik L, et al. Deletion 17q12 is a recurrent copy number variant that confers high risk of autism and schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clissold RL, Shaw-Smith C, Turnpenny P, Bunce B, Bockenhauer D, Kerecuk L, Waller S, Bowman P, Ford T, Ellard S, et al. Chromosome 17q12 microdeletions but not intragenic HNF1B mutations link developmental kidney disease and psychiatric disorder. Kidney Int. 2016;90:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dubois-Laforgue D, Cornu E, Saint-Martin C, Coste J, Bellanné-Chantelot C, Timsit J. Diabetes, Associated Clinical Spectrum, Long-term Prognosis, and Genotype/Phenotype Correlations in 201 Adult Patients With Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1B (HNF1B) Molecular Defects. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1436–43. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bell JT, Pai AA, Pickrell JK, Gaffney DJ, Pique-Regi R, Degner JF, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. DNA methylation patterns associate with genetic and gene expression variation in HapMap cell lines. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R10. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibbs JR, van der Brug MP, Hernandez DG, Traynor BJ, Nalls MA, Lai SL, Arepalli S, Dillman A, Rafferty IP, Troncoso J, et al. Abundant quantitative trait loci exist for DNA methylation and gene expression in human brain. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hannon E, Spiers H, Viana J, Pidsley R, Burrage J, Murphy TM, Troakes C, Turecki G, O'Donovan MC, Schalkwyk LC, et al. Methylation QTLs in the developing brain and their enrichment in schizophrenia risk loci. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:48–54. doi: 10.1038/nn.4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang D, Cheng L, Badner JA, Chen C, Chen Q, Luo W, Craig DW, Redman M, Gershon ES, Liu C. Genetic control of individual differences in gene-specific methylation in human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edghill EL, Bingham C, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Mutations in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta and their related phenotypes. J Med Genet. 2006;43:84–90. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.032854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd M, Shields B, Hammersley S, Hudson M, McDonald TJ, Colclough K, Oram RA, Knight B, Hyde C, Cox J, et al. Systematic Population Screening, Using Biomarkers and Genetic Testing, Identifies 2.5% of the U.K. Pediatric Diabetes Population With Monogenic Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:1879–88. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD, Irizarry RA. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1363–1369. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis S, Du P, Bilke S, Triche T, Jr, Bootwalla M. methylumi: Handle Illumina methylation data. R package version 2.17.0. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen YA, Lemire M, Choufani S, Butcher DT, Grafodatskaya D, Zanke BW, Gallinger S, Hudson TJ, Weksberg R. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics. 2013;8:203–209. doi: 10.4161/epi.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price ME, Cotton AM, Lam LL, Farre P, Emberly E, Brown CJ, Robinson WP, Kobor MS. Additional annotation enhances potential for biologically-relevant analysis of the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6:4. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pidsley R, CC YW, Volta M, Lunnon K, Mill J, Schalkwyk LC. A data-driven approach to preprocessing Illumina 450K methylation array data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:293. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaney C, Garg SK, Yung R. Analysis of DNA methylation by pyrosequencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1343:249–264. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2963-4_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houseman EA, Accomando WP, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, Marsit CJ, Nelson HH, Wiencke JK, Kelsey KT. DNA methylation arrays as surrogate measures of cell mixture distribution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2012;13:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koestler DC, Christensen B, Karagas MR, Marsit CJ, Langevin SM, Kelsey KT, Wiencke JK, Houseman EA. Blood-based profiles of DNA methylation predict the underlying distribution of cell types: a validation analysis. Epigenetics. 2013;8:816–826. doi: 10.4161/epi.25430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feber A, Guilhamon P, Lechner M, Fenton T, Wilson GA, Thirlwell C, Morris TJ, Flanagan AM, Teschendorff AE, Kelly JD, Beck S. Using high-density DNA methylation arrays to profile copy number alterations. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R30. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen BS, Schwartz DA, Yang IV, Kechris KJ. Comb-p: software for combining, analyzing, grouping and correcting spatially correlated P-values. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2986–2988. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hannon E, Dempster E, Viana J, Burrage J, Smith AR, Macdonald R, St Clair D, Mustard C, Breen G, Therman S, et al. An integrated genetic-epigenetic analysis of schizophrenia: evidence for co-localization of genetic associations and differential DNA methylation. Genome Biol. 2016;17:176. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Amen-Hellebrekers CJ, Jansen S, Pfundt R, Schuurs-Hoeijmakers JH, Koolen DA, Marcelis CL, de Leeuw N, de Vries BB. Duplications of SLC1A3: associated with ADHD and autism. Eur J Med Genet. 2016;59:373–376. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bedont JL, LeGates TA, Slat EA, Byerly MS, Wang H, Hu J, Rupp AC, Qian J, Wong GW, Herzog ED, et al. Lhx1 controls terminal differentiation and circadian function of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Cell Rep. 2014;7:609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y, Kwan KM, Mailloux CM, Lee WK, Grinberg A, Wurst W, Behringer RR, Westphal H. LIM-homeodomain proteins Lhx1 and Lhx5, and their cofactor Ldb1, control Purkinje cell differentiation in the developing cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13182–13186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705464104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drews C, Senkel S, Ryffel GU. The nephrogenic potential of the transcription factors osr1, osr2, hnf1b, lhx1 and pax8 assessed in Xenopus animal caps. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lokmane L, Heliot C, Garcia-Villalba P, Fabre M, Cereghini S. vHNF1 functions in distinct regulatory circuits to control ureteric bud branching and early nephrogenesis. Development. 2010;137:347–357. doi: 10.1242/dev.042226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohanty V, Akmamedova O, Komurov K. Selective DNA methylation in cancers controls collateral damage induced by large structural variations. Oncotarget. 2017;8:71385–92. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Donovan SM, Hasselfeld K, Bauer D, Simmons M, Roussos P, Haroutunian V, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE. Glutamate transporter splice variant expression in an enriched pyramidal cell population in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e579. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma D, Shield JP, Dean W, Leclerc I, Knauf C, Burcelin RR, Rutter GA, Kelsey G. Impaired glucose homeostasis in transgenic mice expressing the human transient neonatal diabetes mellitus locus, TNDM. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:339–348. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Du X, Rousseau M, Ounissi-Benkalha H, Marchand L, Jetha A, Paraskevas S, Goodyer C, Polychronakos C. Differential expression pattern of ZAC in developing mouse and human pancreas. J Mol Histol. 2011;42:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s10735-011-9315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. SLC1A3 bisulfite pyrosequencing assay conditions. (XLSX 11 kb)

Figure S1. This figure illustrates the extent of the 17q12 deletion in each patient as estimated by the CNV calling algorithm within the CHAMP package. (PDF 15 kb)

Table S2. All anlaysed probes from the ANOVA test with a p-value <0.01. (XLSX 688 kb)

Table S3. Probes that are significantly differentaly methylated in both of the separate group analyses (note that all probes are in the same direction in both analyses). (XLSX 19 kb)

Figure S2. This Figure shows four significant differentially methylated regions (DMRs) identified between controls and 17q12 deletion carriers. A) SYNRG (corrected P = 1.32E-17), B) AATF (corrected P = 1.64E-11). C) LHX1 (corrected P = 3.37E-18), D) SMIM24 (corrected P = 1.01E-07). (PDF 223 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.