Abstract

Background:

Although acne is principally a disorder of adolescence, the number of adult patients with acne is increasing. Adult acne is defined as the presence of acne beyond the age of 25 years. There is relatively few data on the prevalence and studies of acne in adult population.

Aim and Objectives:

To analyze the various factors that aggravate or precipitate acne vulgaris in Indian adults.

Materials and methods:

The study was done at the Department of Dermatology at a tertiary care center in Kerala for a period of 1 year. A total of 110 patients above the age of 25 year diagnosed clinically as acne vulgaris were included in the study. A detailed history regarding age of onset, duration, type of acne, family history, whether there was any exacerbation related to food, cosmetics, drugs, emotional stress, seasonal variation, sunlight, sweating, pregnancy, menstruation and smoking was taken.

Results:

Majority of patients with adult acne were in the age group 26-30 years and there was a clear female preponderance. Persistent acne was more common than late onset acne. Food items and cosmetics were attributed to exacerbation by 47.3% and 40% of patients respectively; 32.7% patients had exacerbations during stress, 26.4% following sun exposure and 23.6% after sweating. About 48% patients had first degree relatives with present or past history of acne. Most of the female patients had premenstrual flare of acne, which was much more common among patients with persistent acne. Pregnancy had no effect on acne in majority of patients. Seasonal variation was observed in 44.5% patients, most of them showing exacerbation in summer months.

Conclusion:

Acne as a disease lasts longer, persists into adulthood and requires treatment well into the forties. Unlike teenage acne, where males tend to be affected more commonly, post adolescent acne mainly affects females. It is therapeutically rewarding to identify the concerned triggers and aggravating factors and be able to deal with them.

KEY WORDS: Adult acne, aggravating factors, late onset, persistent

What was known?

Acne beyond the age of 25 years is being increasingly recognized, more common in women, can be persistent adolescent acne or late onset adult acne, etiological factors differ in different studies.

Introduction

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit.[1] It is one of the most common skin disorders worldwide and occurs primarily at puberty with a prevalence of almost 95%.[2]

Acne is characterized by seborrhea, the formation of open and closed comedones, erythematous papules, and pustules and in more severe cases nodules, deep pustules and pseudocysts.[1] It is a multifactorial disease depending on genetic predisposition, endocrine factors, follicular epidermal hyperproliferation, excess sebum production, inflammation, the colonization and activity of Propionibacterium acnes, and environmental factors.[3]

Multiple factors have been proposed to cause precipitation or aggravation of acne including cosmetics, drugs, sunlight, and seasonal variation. Recent studies suggest that diet could play an important role in the pathogenesis of acne.[4] Stress is frequently implicated in the aggravation of acne while acne itself induces stress.[5] Although acne is principally a disorder of adolescence, the prevalence of adult patients with acne is increasing. Adult acne has been traditionally defined as the presence of acne beyond the age of 25 years. There are two types of adult acne; persistent acne and late-onset acne. Adolescent acne persisting beyond the age of 25 years is called persistent adult acne and acne developing for the first time after the age of 25 years is called late-onset adult acne. Both these types are more common in women. In persistent acne, patients have lesions on most days and may experience a premenstrual flare. Late-onset acne can be further subdivided into chin acne, which occurs around the chin and perioral area, is inflammatory, and flares premenstrually and sporadic acne which occurs suddenly in adult life with no distinguishing features.[6]

There are relatively few data on the prevalence and studies of acne in the adult population. In this context, a systematic study on the clinical profile of adult acne vulgaris with particular reference to the precipitating and aggravating factors will help in understanding its pathogenesis and management.

Subjects and Methods

The study comprised of 110 patients with a clinical diagnosis of adult acne vulgaris who attended the outpatient clinic of the Department of Dermatology, Academy of Medical Sciences, Pariyaram, during a period of 1 year from January 2015 to December 2015. Approval for the study was obtained from the ethics committee, and written informed consent was taken from all the patients.

A detailed history regarding age of onset, duration, type of acne, family history, whether there was any exacerbation related to food, cosmetics, drugs, emotional stress, seasonal variation, sunlight, or menstruation was taken.

Statistical analysis

Data collected were tabulated in a Microsoft Excel worksheet, and a computer-based analysis of the data was performed using SPSS Version 24 (Kerala state co-operative hospital complex & center for advanced medical sciences Ltd. No. 4386, Kannur, Kerala, India).

Results

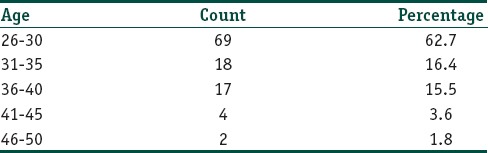

The mean age of patients in year was around 30.9±5.4. The youngest patient was 26 year old and the oldest one was 49 year. Sixty-nine (62.7%) patients in this study were in the age group between 26 and 30 years followed by 18 patients (16.4%) in the age group 31–35 years [Table 1]. Forty-six patients (41.8%) had a duration of <5 years whereas 14 (12.7%) patients had a total duration of >15 years. Out of the 110 patients included in the study, 89 (80.9%) were female and 21 (19.1%) were male. There was a clear female predominance with a female-to-male ratio 4.24:1. Regarding the type of acne, 64 patients (58.2%) had persistent acne and 46 patients (41.8%) had late-onset acne. Fifty-three (48.2%) patients had first-degree relatives with a present or past history of acne.

Table 1.

Percentage distribution of the sample according to age

Precipitating factors

Fifty-two (47.3%) patients could attribute their exacerbation of the lesions to the intake of different types of food items. Forty-one (37.3%) noticed exacerbation most of the times after intake of oily food, 23 (20.9%) after intake of meat, and 11 (10%) after consuming high glycemic diet. Forty-four (40%) patients reported aggravation of lesion after using some form of cosmetics of which 27 (24.5%) had aggravation after applying skin-lightening agents, 16 (14.5%) after doing facial, and 10 (9.1%) after using hair oils. Three (2.7%) patients noticed aggravation of lesions after applying topical steroids. Thirty-six (32.7%) patients had exacerbations during periods of emotional stress and 29 (26.4%) following sun exposure. Majority of patients, i.e. 61 (55.5%) reported no seasonal aggravation of acne whereas 47 (42.7%) patients had exacerbation in summer and 2 (1.8%) in winter.

Out of the total 89 females in the study, 6 (6.7%) patients had irregular cycles. Seventy (78.7%) patients reported premenstrual flare of acne of which 42 (60%) had persistent acne and 28 (40%) had late-onset acne, and this difference was found to be statistically significant (P< 0.05).

Discussion

Acne is traditionally considered as a disease of adolescents, and there are only few studies on postadolescent or adult acne. In a hospital-based Indian study, 9.4% patients (29 out of 309) were more than 25 years of age.[7] In our study, the mean age of patients in years was around 30.9. The youngest patient was 26 year old and the oldest one was 49 year old. Two patients were beyond the age of 45 year. This was in accordance with a study on adult acne conducted by Khunger and Kumar where 2.1% of patients were beyond 45 year.[6] In comparison, Goulden et al. reported acne in 12.5% of patients beyond 45 year.[4] Adult acne is more common in women.[3,4] Similarly, in our study, women were predominantly affected (80.9%) as compared to men (19.1%).

In the study done by Khunger and Kumar, acne was persistent from adolescence in a majority of patients (73.2%)[6] whereas Goulden et al. noted that 82% of the study population had persistent acne.[4] Similarly, of the 110 patients in our study, 64 patients (58.2%) had persistent acne and 46 patients (41.8%) had late-onset acne.

Historically, much debate has surrounded the subject of diet in the management of acne. Cordain et al. postulated that high glycemic diets may be a significant contributor to the high prevalence of acne seen in Western countries.[8] It was hypothesized that milk and dairy products carried hormones and bioactive molecules that had the potential to aggravate acne. Fifty-two (47.3%) patients in our study could attribute their exacerbation of the lesions to the intake of different types of food items. Forty-one (37.3%) noticed exacerbation most of the times after intake of oily food, 23 (20.9%) after intake of meat, and 11 (10%) after consuming high glycemic diet. Two (1.8%) patients reported aggravation after intake of dairy products whereas 8 (7.3%) patients after consuming nuts, chocolates, etc.

Many cosmetics including some sunscreens are comedogenic. Some well-known comedogenic cosmetic ingredients are isopropyl myristate, lanolin, butyl stearate, stearyl alcohol, and oleic acid.[5] Facials were observed to have caused acneiform eruptions in 33.1% of participants in a study in India.[9] Oils form an occlusive film over the applied area and may cause comedogenesis and aggravation of acne. Most sunscreens are too oily for acne patients and tend to aggravate it. Khunger and Kumar observed that only 40 patients (22%) out of 176 using some form of cosmetics had aggravation due to cosmetic use. In our study, 44 (40%) patients reported aggravation of lesion after using some form of cosmetics of which 27 (24.5%) had aggravation after applying skin-lightening agents, 16 (14.5%) after doing facial, and 10 (9.1%) after using hair oils. None of them noticed any exacerbation after using sunscreens.

The well known causative drugs of acne are corticosteroids, anabolic steroids, antiepileptics, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antitubercular drugs, antineoplastics, etc.[10] In this study, 3 (2.7%) patients noticed aggravation of lesions after applying topical steroids. No other drugs were reported as an exacerbating factor. Steroids have been implicated in the causation of acne by inducing hyperproliferation of the upper portion of pilosebaceous unit. Khunger and Kumar observed that there was no significant relation with drug usage in their patients, except the use of topical steroids which caused aggravation in all the patients applying it (11.8%).[6]

Stress is frequently implicated in the aggravation of acne while acne itself induces stress.[5] In our study, 36 (32.7%) patients reported exacerbation during periods of emotional stress. In the study of Khunger and Kumar, 25.7% of patients reported stress as an aggravating factor,[6] in contrast to Goulden et al., who reported that in 71% of their patients acne flared with stress.[4]

Sunlight is generally beneficial to acne although psoralen and ultraviolet A therapy may sometimes induce or aggravate acne. According to Engel et al., sun exposure had positive association with exacerbation of acne vulgaris.[11] In our study, 29 (26.4%) patients reported aggravation following sun exposure. This was in accordance with a study conducted by Khunger and Kumar where sunlight exposure was responsible for aggravation in 93 (33.2%) patients.[6]

An Indian study by Sardana et al. showed that majority of patients with acne vulgaris worsened during summer.[12] In our study, majority of patients (55.5%) reported no seasonal variation of acne whereas 42.7% of patients had exacerbation in summer and 1.8% in winter. Khunger and Kumar in their study reported summer season as an aggravating factor in 36.7% of patients.

It has been suggested that acne might be familial according to the results of a large study of identical twins showing 97.9% affliction.[13] Khunger and Kumar reported that 38.8% of patients had at least one first-degree relative affected with clinical acne.[6] In our study, 48.2% of patients had first-degree relatives with present or past history of acne.

Out of the total 89 females in our study, 6 (6.7%) patients had irregular cycles and 78.7% of patients reported premenstrual flare of acne. This was in accordance with the study conducted by Goulden et al. in which premenstrual flare was reported in 84.8% of patients. This was in contrast to Khunger and Kumar who observed premenstrual flare in only 11.7% of patients.[6] The explanation offered for premenstrual flare was hydration-induced cyclical narrowing of the pilosebaceous orifice between days 16 and 20 of the menstrual cycle. Progesterone and estrogen had pro- and anti-inflammatory effects, and alteration or modulation of these hormones might be another explanation.[14] In persistent acne, patients had lesions on most days and might experience a premenstrual flare.[6] Late-onset acne could be further subdivided into chin acne, which occurred around the chin and perioral area, was inflammatory, and flared premenstrually and sporadic acne which occurred suddenly in adult life with no distinguishing features.[6,10] Out of the 70 (78.7%) patients reported to have premenstrual flare of acne, 42 (60%) had persistent acne and 28 (40%) had late-onset acne.

Conclusion

Acne as a disease lasts longer and persists into adulthood even into the forties. Unlike adolescent acne, adult acne is predominant in women. It is therapeutically rewarding to identify the concerned triggers and aggravating factors of adult acne. While complete avoidance is not a reasonable possibility all the time, minimizing them can help patients to reduce the chance of flare-ups.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Adult acne affects females predominantly; persistent adolescent acne is more common; cosmetics especially fairness creams and food play important role; mean age is 30 year but can persist beyond 40 and most of the patients have stress.

References

- 1.Layton AM. Disorders of the sebaceous glands. In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 42.17–89. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton JL, Cunliffe WJ, Stafford I, Shuster S. The prevalence of acne vulgaris in adolescence. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:119–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1971.tb07195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goulden V, Stables GI, Cunliffe WJ. Prevalence of facial acne in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:577–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post-adolescent acne: A review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:66–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubba R, Bajaj AK, Thappa DM, Sharma R, Vedamurthy M, Dhar S, et al. Acne in India: Guidelines for management – IAA consensus document. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75(Suppl 1):1–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khunger N, Kumar C. A clinico-epidemiological study of adult acne: Is it different from adolescent acne? Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:335–41. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.95450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adityan B, Thappa DM. Profile of acne vulgaris – A hospital-based study from South India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:272–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.51244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordain L, Lindeberg S, Hurtado M, Hill K, Eaton SB, Brand-Miller J, et al. Acne vulgaris: A disease of Western civilization. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1584–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.12.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanna N, Datta Gupta S. Rejuvenating facial massage – A bane or boon? Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:407–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams C, Layton AM. Persistent acne in women: Implications for the patient and for therapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:281–90. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engel A, Johnson ML, Haynes SG. Health effects of sunlight exposure in the United States. Results from the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1971-1974. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:72–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sardana K, Sharma RC, Sarkar R. Seasonal variation in acne vulgaris – Myth or reality. J Dermatol. 2002;29:484–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulden V, McGeown CH, Cunliffe WJ. The familial risk of adult acne: A comparison between first-degree relatives of affected and unaffected individuals. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:297–300. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunliffe WJ, Gollnick HP. London: Martin Dunitz; 2001. Acne: Diagnosis and Management; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]