Abstract

Background:

The relationship between impaired quality of life (QoL) due to melasma and its clinical severity remains equivocal despite several studies.

Aim:

The aim was to study the correlation, if any, between the clinical severity and the impairment in QOL due to melasma.

Methods:

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study was conducted on a cohort of 141 patients of melasma attending the outpatient department of our referral hospital. A physician measured the severity of melasma using the melasma area and severity index (MASI), while melasma-related QoL (MELASQOL) score was calculated utilizing the validated Hindi version of the MELASQOL questionnaire filled by the patients. Correlations of these two scores with each other and with components of the demographic data were attempted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.

Results:

Significantly greater impairment in QoL was found in patients with a history of prior use of triple combination therapy and in patients with hirsutism and/or polycystic ovarian disease. The severity of melasma was found to be significantly higher in patients with a history of recurrence and tobacco chewing.

Limitations:

The sample size could have been larger. Ultrasonography could have been carried out in all cases of hirsutism.

Conclusion:

The severity of melasma does not correlate with the impairment in QoL.

Keywords: Melasma area and severity index, melasma, melasma-related quality of life, quality of life

What was known?

Melasma leads to impairment of quality of life

The correlation of melasma related quality of life vis-à-vis its clinical severity remains equivocal.

Introduction

Melasma, a common disorder of acquired hyperpigmentation, is characterized by tan or brown macules/patches localized to photo-exposed areas of the face, particularly the malar areas, forehead, and chin.[1]

Although the impairment in quality of life (QoL) of patients with melasma is well established, its relationship with clinical severity remains equivocal; measures of the latter – such as the commonly used melasma area severity index (MASI)[2] – do not reflect the psychosocial distress experienced by the patients.[1,3] Recognition of this distress is necessary in reassuring patients about their social and emotional problems, thereby contributing to the effective management of melasma. Hence, we undertook this study to find the correlation between severity and impairment in QoL, if any, and with components of demographic data in patients with melasma.

Methods

This cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was carried out after receiving ethical clearance from our institute and comprised of a cohort of 141 patients of melasma attending the outpatient department of our tertiary care hospital. After obtaining their informed consent and demographic details, each patient was asked to fill in without any time limit the recently validated Hindi version[4] of the 10-item melasma QoL (MELASQOL) questionnaire which can usually be completed in 1 min. It incorporates a Likert scale of 1–7 (1, signifying not bothered at all and 7, bothered all the time); higher the score, worse is the QoL, ranging from 10 to 70.[5]

The clinical severity was assessed using MASI which is calculated by the subjective assessment of three factors: area (A) of involvement, darkness (D), and homogeneity (H). The face is divided into four regions: forehead (f), right malar (rm), left malar (lm), and chin (c); the first three weighted 30% each and chin, 10%. The area of involvement in each of these 4 facial regions is given a numeric value of 0–6 (0 = no involvement; 1 = <10%; 2 = 10%–29%; 3 = 30%–49%; 4 = 50%–69%; 5 = 70%–89%; and 6 = 90%–100%). Darkness and homogeneity are rated on a scale from 0 to 4 (0 = absent; 1 = slight; 2 = mild; 3 = marked; and 4 = maximum). The MASI score = 0.3A(f) (D[f] + H[f]) + 0.3A(lm) (D[lm] + H[lm]) + 0.3A(rm) (D[rm] + H[rm]) + 0.1(c) (D[c] + H[c]), and ranges from 0 to 48.

Quantitative variables were described using percentages, ranges, means, and standard deviations. Student's independent t-test, analysis of variance test, and Spearmen correlation analysis were carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) as appropriate. A two-tailed probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data

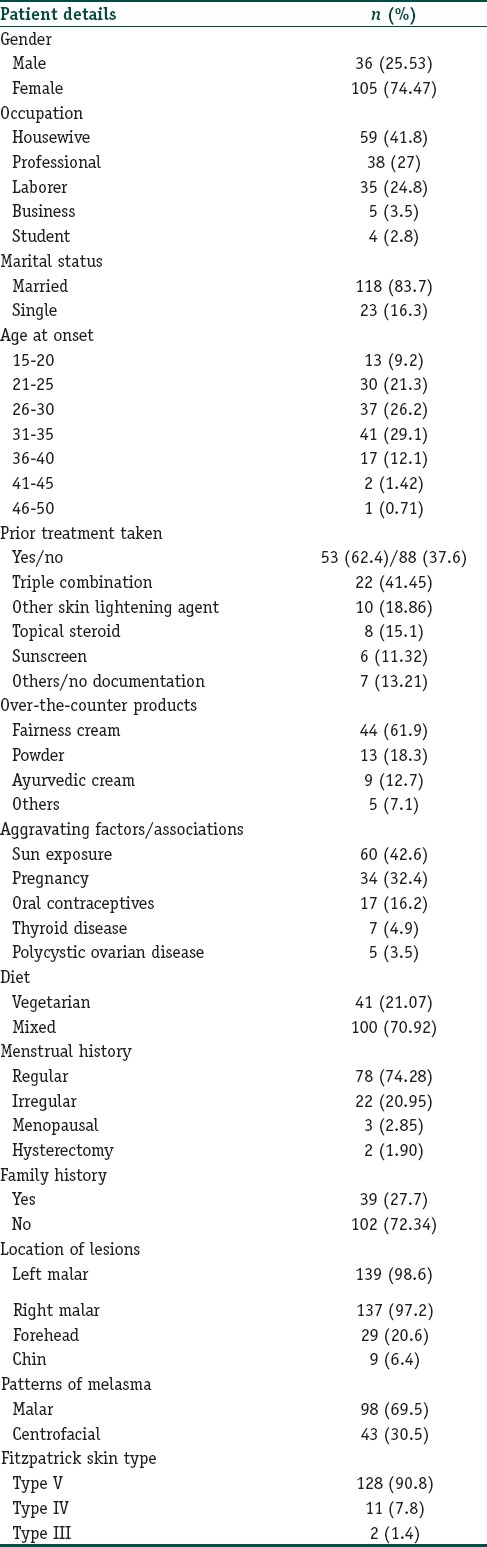

One hundred and forty-one patients (males, 36; females 105), with age ranging from 20 to 76 (mean: 32.35±7.427) years constituted our study population; their main occupations being, housewives (59; 41.8%), professionals (38; 27%), and laborers (35; 24.8%). One hundred and eighteen patients (83.7%) were married; 23 (16.3%), single and none, divorced. Melasma lesions were first noticed between the ages of 31 and 35 years by 41 (29.1%); 26–30 years by 37 (26.2%) and 21–25 years by 30 (21.3%) patients. The duration of melasma ranged from 1 month to 25 (mean, 3.1 ± 3.39) years. Majority (88; 62.4%) of the patients presented during their first spell of melasma; remaining (53; 37.6%), after having had treatment for a mean duration of 5.92 (±6.028) months: 22 (41.45%) with the triple combination; 10 (18.86%) with other skin lightening agents and 8 (15.1%) with topical steroids [Table 1]. Of the seventy-one (50.35%) patients who admitted using over-the-counter treatment for >6 months, 44 (61.9%) used fairness cream; 13 (18.3%), powder; 9 (12.7%), ayurvedic cream and 5 (7.1%), other applications. Sun exposure was the principal aggravating factor in 60 (42.6%) of our study population. The onset of melasma was associated with pregnancy in 34 (32.4%) and with intake of oral contraceptives in 17 (16.2%) cases. Eleven (7.8%) patients gave a history of chewing tobacco; 1 (0.7%) each of smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol and another one who smoked cigarettes as well as drank alcohol. Of the seven (4.9%) cases with a history of thyroid disease, 6 (85.71%) were female. History of melasma in first-degree relatives was given by 39 (27.7%) cases. Menses were regular in 78 (74.28%) and irregular in 22 (20.95%) while three (2.85%) females were menopausal and two (1.90%) had undergone hysterectomy. The lesions were present on left malar region in 139 (98.6%); right malar, 137 (97.2%); forehead, 29 (20.6%) and chin, 9 (6.4%). The most common pattern of melasma observed in our study was malar (98;69.5%) followed by centrofacial (43;30.5%). Body mass index (BMI) ranged between 15.43 and 33.87 (mean; 21.75 ± 3.07); 9 (6.38%) having a BMI between 25 and 30 and 4 (2.83%) having a BMI >30.

Table 1.

Clinico-epidemiological details of patients

Melasma-related quality of life score

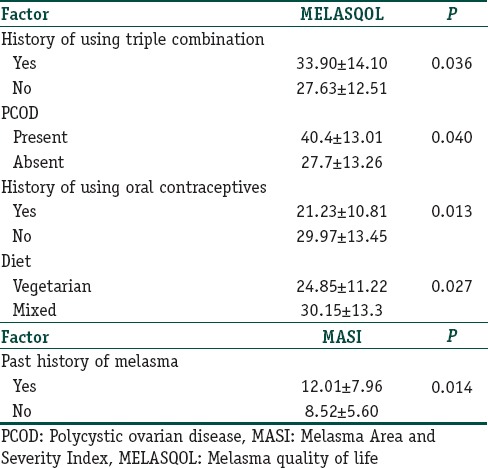

The overall mean MELASQOL score was 28.61 (±12.92; range, 10–64), higher in males (29.25±12.44) than in females (28.39±13.13). Question 8, i.e., “skin discoloration making you feel unattractive to others,” had the highest mean score (4.16±2.215); while question 7, i.e., “skin condition making it hard to show affection,” the lowest (2.12±1.742). While MELASQOL score was found to have a significant negative correlation (ρ=-0.170; P=0.044) with the duration of disease, no correlation was found with gender, occupation, marital status, age at onset, positive family history, menstrual history, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, history of thyroid disease, BMI, skin type, location of lesions, and the pattern of melasma [Table 2]. The patients who had used triple combination before presenting to our hospital (22; 15.60%) had a significantly greater MELAQOL score (33.90±14.10) than those who had not used any treatment (27.63±12.51; P=0.036). MELASQOL score of patients who had taken treatment other than with the triple combination was not affected significantly. Three female patients with polycystic ovarian disease (PCOD) had significantly higher MELASQOL score (44±15.52; P=0.041) than those without (27.91±13.2). Five cases (4.8%) with hirsutism (three, known PCOD patients; two, neither having symptoms of PCOD nor ultrasonic evidence thereof), too, had a significantly higher MELASQOL score (40.4±13.01; P=0.040) than those who did not (27.7±13.26). Surprisingly, females who took oral contraceptives (17, 16.2%) had a significantly lower MELASQOL score (21.23±10.81; P=0.013) than those who did not (29.97±13.45). Vegetarians (41; 29.07%), too, had a significantly lower MELASQOL score (24.85±11.22; P=0.027) than those who consumed a mixed diet (30.15±13.3).

Table 2.

Statistically significant correlations of Melasma Quality of Life and Melasma Area and Severity Index

Melasma area and severity index score

The overall mean MASI score in our study was 9.07 (±6.12; range, 1.20–32.40); the highest individual scores being for the right (3.97) and left (3.86) malar regions. The MASI score was found to be higher in female (9.32±6.46) than in male (8.33±5.03), though not significantly so. MASI correlated significantly with the age of the patient (ρ=0.178; P=0.035) but not with the duration of their melasma [Table 2]. Patients who had melasma in the past (22; 15.6%) had a significantly higher MASI (12.01±7.96) than those who presented with the first episode (8.52±5.60; P=0.014).

Patients who chewed tobacco (11; 7.8%) had a significantly higher MASI (13.33±6.68) than those who did not (8.71±5.96; P=0.016). Positive family history, menstrual history, diet, BMI, skin type, location of lesions, pattern of melasma, history of previous treatment, sun exposure, PCOD, stress, intake of oral contraceptives revealed no correlation with the MASI score.

QoL vis-a-vis clinical severity

There was no correlation between the MELASQOL-and MASI scores (ρ=0.151; P=0.074).

Discussion

Our study, like previous Indian studies, revealed a marked female preponderance (F:M=3:1).[6] However, this preponderance was found to be lower than various South East Asian (Malaysia, 6:1; Indonesia, 24:1; Singapore, 21:1) and South American (Brazil, 39:1) studies.[7,8]

The mean age of our cases (32.35±7.427 years) as well as of most studies from India[7] was found to be lower than studies conducted in Singapore[9] (42.3 years) and Brazil[10] (38.43 years).

Only the malar (69.5%) and centrofacial (30.5%) patterns were found in our study, similar (malar, 65.9%; centrofacial, 34.1%) to an Iranian study of 400 cases.[11] The absence of the mandibular pattern was also reported by a Korean study, 52% and 48% of whose participants had the centrofacial and malar patterns, respectively.[12] However, in contrast to our study, centrofacial preponderance has been reported by most Indian studies, the largest with 312 cases revealing centrofacial (54.44%), malar (43.26%) and mandibular (1.6%) patterns.[9]

A history of aggravation by the sun, given by 42.6% of our cases was also reported by 55.5% cases of another Indian study.[9] A positive family history of melasma that was seen in 27.7% of our cases was reported by ~ 33.33% participants in the same Indian study.[9]

Though not statistically significant, the MELASQOL score in our study was surprisingly found to be higher among males than in females. However, the total mean MELASQOL score (28.61) in our study was lower than most other Indian and foreign studies,[1] being higher than only a single French study (20.9),[13,14] suggesting lesser concern about cosmesis among patients of our study.

Unlike the significant positive correlation between the duration of melasma and MELASQOL score in Mexican and French studies.[13,14] our study had a significantly negative correlation between these parameters; the same could possibly be a result from a tendency of our people to come to terms with their condition with the passage of time. However, our study along with some others[5,13,14] revealed that cases treated previously for melasma had a significantly higher MELASQOL than those who had received no treatment, suggesting there to be a “paradoxical” increase in impairment of QOL with attempted treatment.

The significantly higher MELASQOL score of our patients having PCOD and/or hirsutism could probably result from the cumulative impact of manifestations of their underlying disorders while the significantly lesser impairment of QoL in cases taking oral contraceptives from their, somewhat, lower MASI. The “confounding” finding of significantly lesser MELASQOL score in our study patients on a vegetarian diet versus — those on mixed — needs unraveling by future larger studies.

The lower mean MASI score (9.07) in our study — as compared to that of Brazilian (10.6), American (14.68), Singaporean (12.1), Spanish (10), and north Indian (20) studies[1,4,15] could be due to the preponderance of the malar (69.5%) pattern in our study along with other racial and/or environmental factors.

The significant correlation of MASI score with the age at presentation but not the duration of the disease or the age of onset suggests the possible contribution toward the severity of melasma by multiple unknown factors. The lack of correlation of MASI score with factors such as pregnancy, stress, PCOD, or intake of oral contraceptives in our study was surprising and could probably be due to their episodic nature. Lack of ultrasonography in all cases of hirsutism was one of the limitations of our study. The surprising significant higher MASI score in cases who chewed tobacco in our study also necessitates validation by larger studies.

As compared to cases presenting with their first spell of melasma, those with past history had a significantly higher MASI score; the majority of the latter having gone through pregnancy i.e. could have got primed for a more severe disease course.

QoL based on Hindi version of MELASQOL questionnaire did not correlate with the severity of melasma as assessed by MASI in our study population. A similar lack of correlation in several recent studies – including the original by Balkrishnan et al.,[5] and two studies from South America[4] – suggests the clinical severity to be one among many criteria (known and unknown) with which the patients assess the burden of their disease. Nonetheless, positive correlation between QoL based on MELASQOL/generic questionnaires and the clinical severity of melasma has also been reported in some, including an Indian, studies.[4]

Conclusion

The lack of correlation between the QoL and clinical severity in the present study most likely resulted due to the “paradoxical” decrease in impairment of QoL with the increasing duration of melasma despite its greater severity with age.

A significantly greater impairment of QoL identified with shorter duration of melasma and the presence of PCOD and/or hirsutism in our study is possibly indicative of the requirement of extra sensitivity on the part of the physicians for these patient groups. In general, the patients of melasma may well be treated as per the severity of their lesions, while the revival of their impaired QoL may necessitate in-depth counseling and psychotherapy, as appropriate.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

There was no correlation between impairment in QoL and clinical severity of melasma in our study probably due to the “paradox” of decrease in impairment of QoL with increase in duration and/or age.

Our study identified two groups – those with shorter duration of melasma and those having symptoms of PCOD – of patients with a significantly greater impairment of QoL

Patients treated previously with “triple combination” therapy had a greater impairment in their QoL as compared to those who had taken any other/no treatment.

References

- 1.Lieu TJ, Pandya AG. Melasma quality of life measures. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:269–80. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimbrough-Green CK, Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, Hamilton TA, Bulengo-Ransby SM, Ellis CN, et al. Topical retinoic acid (tretinoin) for melasma in black patients. A vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:727–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheth VM, Pandya AG. Melasma: A comprehensive update: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:689–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar R, Garg S, Dominguez A, Balkrishnan R, Jain RK, Pandya AG, et al. Development and validation of a Hindi language health-related quality of life questionnaire for melasma in Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:16–22. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.168937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkrishnan R, McMichael AJ, Camacho FT, Saltzberg F, Housman TS, Grummer S, et al. Development and validation of a health-related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(3):572–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krupa Shankar DS, Somani VK, Kohli M, Sharad J, Ganjoo A, Kandhari S, et al. A cross-sectional, multicentric clinico-epidemiological study of melasma in India. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2014;4:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s13555-014-0046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sivayathorn A, Apichati S. Melasma in Orientals. Clin Drug Investig. 1995;10:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pawar S, Khatu S, Gokhale N. A Clinico-Epidemiological Study of Melasma in Pune Patients. Journal of Pigmentary Disorders; 2. Epub ahead of print. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: A clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikino JK, Nunes DH, Silva VP, Fröde TS, Sens MM. Melasma and assessment of the quality of life in Brazilian women. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:196–200. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moin A, Jabery Z, Fallah N. Prevalence and awareness of melasma during pregnancy. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:285–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, Kim J, Lee KB, Yim H, et al. Melasma: Histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228–37. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-0963.2001.04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Misery L, Schmitt AM, Boussetta S, Rahhali N, Taieb C. Melasma: Measure of the impact on quality of life using the French version of MELASQOL after cross-cultural adaptation. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:331–2. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cestari TF, Hexsel D, Viegas ML, Azulay L, Hassun K, Almeida AR, et al. Validation of a melasma quality of life questionnaire for Brazilian Portuguese language: The MelasQoL-BP study and improvement of QoL of melasma patients after triple combination therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156(Suppl 1):13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominguez AR, Balkrishnan R, Ellzey AR, Pandya AG. Melasma in Latina patients: Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a quality-of-life questionnaire in Spanish language. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]