Abstract

Background:

Vitiligo is a depigmenting cutaneous disorder with complex pathogenesis. Thiol compounds are well-known organic structures that play a major role in melanogenesis.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to determine the association between plasma thiol level and disease severity in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Methods:

A total of 73 patients with nonsegmental vitiligo (57 generalized and 16 localized type) and age- and sex-matched 69 healthy controls were enrolled in the study. Plasma levels of native thiols, disulfides, and total thiols were measured by a novel and automated assay. Disease severity of vitiligo was assessed with Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI) score. The extent, stage, and spread of vitiligo of patients were evaluated according to the Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF) system.

Results:

The native and total thiol levels of vitiligo patients were higher than those of healthy control group (P≤0.001 and 0.001, respectively). The median VASI score of patients was 0.7 (0.02–28.30). Univariate analyses showed that plasma native thiol levels, VETF spread score, disease duration, and vitiligo type significantly correlated with VASI scores (r=0.237, P=0.043; r=0.458, P<0.001; and P<0.001, respectively). Stepwise multivariate analysis revealed that disease duration (β=0.017; P=0.005) and spread score (β=1.301; P=0.001) were found statistically significant as independent factors on VASI score.

Conclusion:

Although plasma native thiol level significantly correlated with VASI scores of patients, it is not a predictive factor for vitiligo severity.

KEY WORDS: Disease activity, pathogenesis, thiol, vitiligo

What was known?

Autoimmune theory alone does not explain the vitiligo pathogenesis as a whole

Thiol compounds are well-known organic structures that play a major role in melanogenesis

Increased levels of thiols are associated with pheomelanin production and pigment loss.

Introduction

Vitiligo is a multigenic cutaneous disorder with complex pathogenesis. Although autoimmunity causing a melanocyte-specific response with adaptive immunity is currently considered as the main pathway, this theory alone does not explain the pathogenesis as a whole. Intrinsic defects within melanocytes including oxidative stress, melanocytorrhagy, neural mechanisms, adhesion defects, and inflammasomes are the other different mechanisms proposed to involve in vitiligo lesions.[1]

Thiols, the organic compounds having sulfhydryl (-SH) groups are present as albumin thiols, protein thiols, and less as low-molecular-weight thiols such as cysteine, cysteinylglycine, glutathione (GSH), homocysteine and gamma-glutamylcysteine human plasma.[2,3] In a dynamic thiol/disulfide homeostasis, these compounds have disulfide bounds under oxidative conditions, which can be reduced to native thiols. Dynamic thiol/disulfide homeostasis regulates the maintenance of antioxidants, detoxification, apoptosis, and many cellular signal mechanisms involving cell division and cell growth.[4,5,6] Thiol compounds play a major role in melanogenesis.[7] Vitiligo presents with mainly depigmented patches, which is the reflection of impaired melanogenesis. The link between melanogenesis and thiol compounds suggested that there may be a link between plasma thiol levels and vitiligo severity. Currently, we can detect the plasma levels of native and total thiols and disulfide levels by a simple, cheap, practical, and automatic novel assay.[8] In the present study, we investigated the association of plasma thiol levels and disease severity in patients with nonsegmental vitiligo.

Materials and Methods

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the hospital. All participants signed written informed consent form.

Subjects

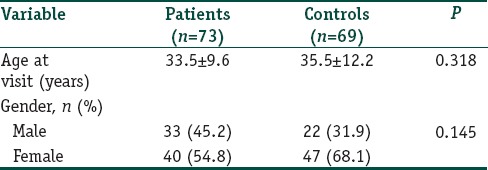

This case–control study was carried out in the outpatient clinic of Dermatovenereology, Ataturk Training and Research Hospital, Ankara. The study enrolled 73 patients with nonsegmental and focal vitiligo diagnosed by dermatological and Wood lamp examination (33 men and 40 women) and 69 healthy controls (22 men and 47 women), matched for age and gender [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of some demographic features of vitiligo patients and healthy controls

Patients who were on topical therapy for 1 month or phototherapy for 3 months before enrollment and who had systemic disease except thyroid disease were excluded from the study. Patients and controls did not have other dermatological diseases, alcohol consumption, and any systemic treatment or antioxidants. Pregnant and nursing individuals were not included in the study. None of the patients had segmental vitiligo.

The demographic and clinical variables of patients were noted on an evaluation sheet designed according to the report of Vitiligo European Task Force (VETF).[9] Clinical scoring was performed according to the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI)[10] and the extent, stage, and spread of vitiligo of patients were evaluated according to the VETF system.[9]

Blood samples and analysis of plasma thiol and disulfide levels

Venous blood samples of all participants were collected in tubes containing EDTA after fasting overnight. Plasma samples were separated from cells by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The samples were run immediately. In this novel assay, sodium borohydride (NaBH4) was used to reduce the disulfide bonds to the thiol groups. The unused NaBH4 remnants are completely removed by formaldehyde. This prevented the extra reduction of the 5,5’-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and further reduction of the formed disulfide bond, which were produced after the DTNB reaction. The total thiol content of the sample was measured using modified Ellman reagent. Native thiol content was subtracted from the total thiol content and half of the obtained difference gave the disulfide bond amount. After manual spectrophotometric optimization studies, parallel tests were applied using an automated analyzer (Cobas c501, Roche). Values were presented as μmol/L.[8]

Statistical analysis

Normality of the continuous variables was evaluated with Shapiro–Wilks test. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and were compared using the Student t-test for two independent groups. Continuous variables that were not normally distributed were expressed as median (minimum–maximum) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test for two independent groups. The association between continuous variables was explored by Pearson (normally distributed) or Spearman (nonnormally distributed) correlation analyses. Categorical variables were presented by frequency and percentage. Comparisons between two categorical variables were performed using the Chi-square analysis. Linear regression analysis was used to correlate VASI with other demographic and clinical variables. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 21.0; (IBM, Armonk, NY USA), and significance was set considered statistically significant P <0.05.

Results

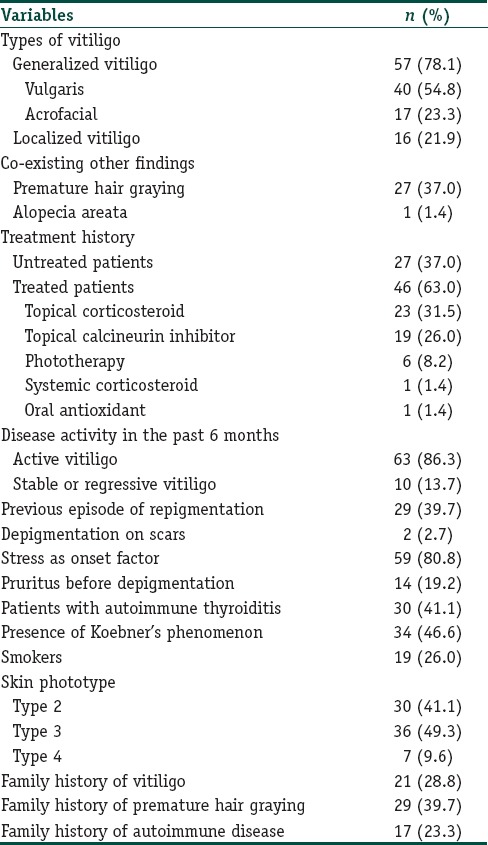

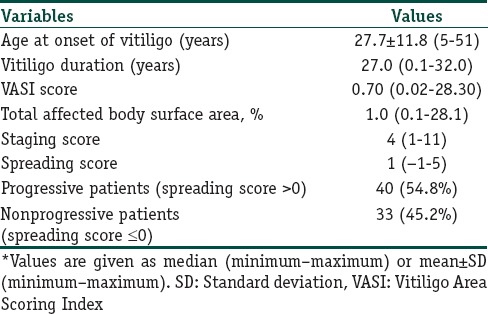

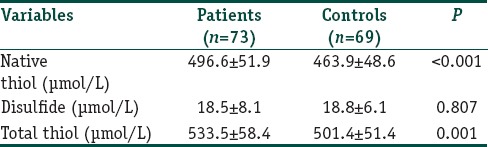

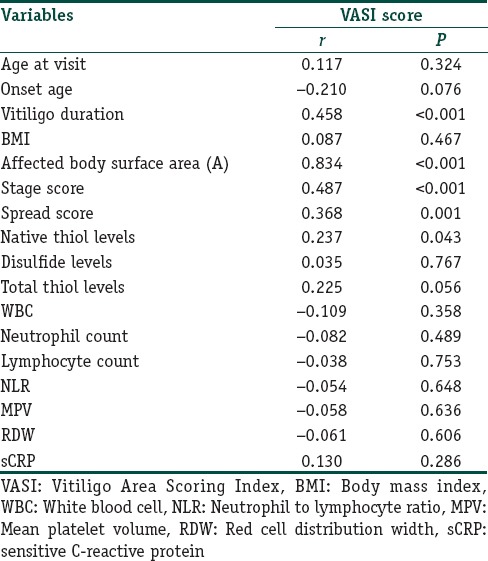

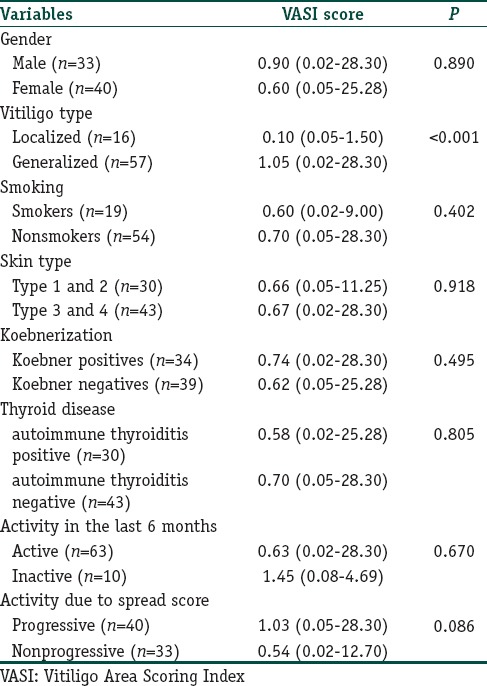

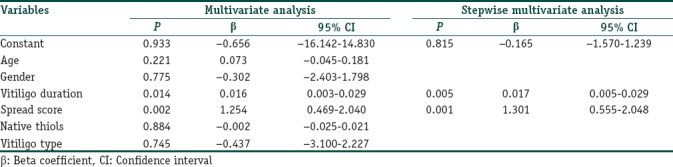

The gender and ages of patients and healthy participants were similar at the examination (P=0.318 and 0.145, respectively); [Table 1]. Of the patients, 78.1% had generalized vitiligo, and 21.9% had localized type. Demographic and clinical features of all patients are given in Tables 2 and 3. The native and total thiol levels of vitiligo patients were higher than those of healthy control group (P <0.001 and 0.001, respectively) [Table 4]. The median VASI score of patients was 0.7 (0.02–28.30). Univariate analysis demonstrated that plasma native thiol levels, VETF stage score, disease duration, affected body surface area, and vitiligo type significantly correlated with VASI scores (r =0.237, P=0.043; r =0.487, P ≤0.001; r =0.458, P <0.001; r =0.834, P ≤0.001; and P <0.001, respectively) [Tables 5 and 6]. Multiple linear regression analyses were used to assess multivariate relations among native thiol, age, gender, vitiligo duration, spread score, and vitiligo type [Table 7]. Since both VASI and stage score were closely related with pigmentation amount and VASI calculation was related with affected body surface area, we did not include these parameters for further statistical analyses. After stepwise method, disease duration (β=0.017; P=0.005) and spread score (β=1.301; P=0.001) were found statistically significant as independent factors on VASI score.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of vitiligo patients

Table 3.

The clinical characteristics of vitiligo patients*

Table 4.

Serum thiol levels of vitiligo patients and control subjects

Table 5.

Correlation analyses between Vitiligo Area Scoring Index score and some demographic and clinical features and laboratory data of vitiligo patients

Table 6.

Comparison of Vitiligo Area Scoring Index scores between some demographic and clinical parameters of vitiligo patients

Table 7.

Multivariate linear regression analysis showing independent variables associated with Vitiligo Area Scoring Index score

Discussion

Vitiligo is mainly considered to be an autoimmune disorder of the skin melanocytes whereas many nonautoimmune mechanisms such as oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways are also suggested to involve in the disease pathogenesis.[1] Researches about melanogenesis led new proposals about impairment of melanogenesis in vitiligo. Thiol compounds were well-known organic structures that played a major role in melanogenesis.[7,11,12] Glutathione (GSH), the active –SH compound of human skin extract, was found to be associated with the inhibition of melanogenesis in human epidermis.[13,14] van Scott et al. reported that the sulfhydryl content of vitiliginous skin was lower than that of the normal skin surrounding the lesions.[15] Although melanocyte death was considered to be involved in vitiligo, depigmented patches were reported to consist of both eumelanin and mainly pheomelanin.[16] The key factor for pheomelanogenesis was the presence of thiol groups of cysteine molecule.[7,11,12] Thiol groups chelated with the copper part of the tyrosinase enzyme and inhibited melanogenesis.[17] The thiol-dopaquinon reaction shifted eumelanogenesis to pheomelanogenesis. Increased levels of thiols including GSH were associated with pheomelanin production and pigment loss.[18]

Pheomelanogenesis was suggested to be an adaptive excretion mechanism which removed excess thiol compound, cysteine.[19] Pheomelanin had pro-oxidant features[20] whereas eumelanin served as a scavenger of reactive oxygen derivate.[21] Pheomelanogenesis resulted in the consumption of GSH which served as the main cysteine source and which acted as an important antioxidant.[11,12] Pheomelanin caused oxidative lipid injury in the cells[22] and induction of apoptosis.[23] Some researchers suggested that the inhibition of tyrosinase activity or other factors causing pheomelanogenesis were involved in vitiligo pathogenesis.[16]

There had been many investigations about the amount of some thiol compounds such as GSH and homocysteine and enzyme activities involving the production and catabolization of these products in vitiligo patients and their relationship with disease severity.[24,25,26] However, plasma thiol levels and its role in vitiligo had not been investigated before. Since thiol-containing compounds were not stable in a dynamic organism, we considered that the systemic impact of thiol compounds, rather than isolated effects of individual ones, might have an important impact on vitiligo pathogenesis. Using a novel, practical, and automated assay developed by Erel and Neselioglu helped us to detect the native and total thiol levels and disulfide levels in plasma of vitiligo patients.[17] We detected higher plasma levels of native thiols which were related to increased systemic levels of organic compounds having sulfhydryl (-SH) groups. Furthermore, plasma native thiol levels closely correlated with vitiligo severity. Our findings pointed to the potential role of excess thiol compounds in vitiligo pathogenesis using possible associated increase of pheomelanogenesis, pheomelanin-induced oxidative stress, cell injury, or apoptosis in vitiligo. The major limitation of our study was the lack of investigation on the relationship between circulating thiol levels and amounts of thiol and pheomelanin in vitiligo and nonvitiligo skin. In addition, multivariate analyses revealed that plasma native thiol levels were not independent predictive factors on vitiligo severity. However, we considered that the present study was a preliminary study leading future investigations about the possible link between vitiligo-pheomelanogesis-increased levels of circulating thiol levels. Increased production or diminished catabolism of–SH compounds might result in higher systemic levels of native thiols. The enzymatic pathways in -SH metabolism might be also impaired in vitiligo.

Conclusion

The present study was the first one which investigated the relationship between plasma thiol levels and vitiligo severity. Although plasma native thiol level closely correlated with VASI score of patients, it was not a predictive factor for vitiligo severity. Further studies are needed to determine whether systemic thiol metabolism is related to the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

Plasma native thiol levels closely correlated with VASI scores. However, it is not a predictive factor for vitiligo severity

Circulating excess thiol compounds may have a potential role in vitiligo pathogenesis.

References

- 1.Speeckaert R, van Geel N. Vitiligo: An update on pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:733–44. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sen CK, Packer L. Thiol homeostasis and supplements in physical exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:653S–69S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.2.653S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turell L, Radi R, Alvarez B. The thiol pool in human plasma: The central contribution of albumin to redox processes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;65:244–53. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas S, Chida AS, Rahman I. Redox modifications of protein-thiols: Emerging roles in cell signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:551–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Circu ML, Aw TY. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:749–62. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogura R, Knox JM, Griffin AC, Kusuhara M. The concentration of sulfhydryl and disulfide in human epidermis, hair and nail. J Invest Dermatol. 1962;38:69–75. doi: 10.1038/jid.1962.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Ozeki H. Chemical analysis of melanins and its application to the study of the regulation of melanogenesis. Pigment Cell Res. 2000;13(Suppl 8):103–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.13.s8.19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erel O, Neselioglu S. A novel and automated assay for thiol/disulphide homeostasis. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taïeb A, Picardo M, VETF Members The definition and assessment of vitiligo: A consensus report of the vitiligo European task force. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamzavi I, Jain H, McLean D, Shapiro J, Zeng H, Lui H, et al. Parametric modeling of narrowband UV-B phototherapy for vitiligo using a novel quantitative tool: The vitiligo area scoring index. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:677–83. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.6.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jara JR, Aroca P, Solano F, Martinez JH, Lozano JA. The role of sulfhydryl compounds in Mammalian melanogenesis: The effect of cysteine and glutathione upon tyrosinase and the intermediates of the pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;967:296–303. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(88)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyskens FL, Jr, Buckmeier JA, McNulty SE, Tohidian NB. Activation of nuclear factor-kappa B in human metastatic melanomacells and the effect of oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1197–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman S, Krysa HF, Smiljanic AM. Inhibitory-action of human epidermis on melanin formation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1946;62:208. doi: 10.3181/00379727-62-15422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halprin KM, Ohkawara A. Glutathione and human pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:355–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Scott EJ, Rothman S, Greene CR. Studies on the sulfhydryl content of the skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1953;20:111–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.1953.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsad D, Wakamatsu K, Kanwar AJ, Kumar B, Ito S. Eumelanin and phaeomelanin contents of depigmented and repigmented skin in vitiligo patients. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:624–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05440.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamura T, Onishi J, Nishiyama T. Antimelanogenic activity of hydrocoumarins in cultured normal human melanocytes by stimulating intracellular glutathione synthesis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2002;294:349–54. doi: 10.1007/s00403-002-0345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiu L, Zhang M, Sturm RA, Gardiner B, Tonks I, Kay G, et al. Inhibition of melanin synthesis by cystamine in human melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:21–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galván I, Ghanem G, Møller AP. Has removal of excess cysteine led to the evolution of pheomelanin?. Pheomelanogenesis as an excretory mechanism for cysteine. BioEssays. 2012;34:565–8. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denat L, Kadekaro AL, Marrot L, Leachman SA, Abdel-Malek ZA. Melanocytes as instigators and victims of oxidative stress. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1512–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meredith P, Sarna T. The physical and chemical properties of eumelanin. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19:572–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitra D, Luo X, Morgan A, Wang J, Hoang MP, Lo J, et al. An ultraviolet-radiation-independent pathway to melanoma carcinogenesis in the red hair/fair skin background. Nature. 2012;491:449–53. doi: 10.1038/nature11624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeuchi S, Zhang W, Wakamatsu K, Ito S, Hearing VJ, Kraemer KH, et al. Melanin acts as a potent UVB photosensitizer to cause an atypical mode of cell death in murine skin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15076–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403994101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Briganti S, Caron-Schreinemachers AL, Picardo M, Westerhof W. Anti-oxidant defence mechanism in vitiliginous skin increases with skin type. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1212–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silverberg JI, Silverberg NB. Serum homocysteine as a biomarker of vitiligo vulgaris severity: A pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:445–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao BH, Shi M, Chen H, Cui S, Wu Y, Gao XH, et al. Glutathione peroxidase level in patients with vitiligo: A Meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:3029810. doi: 10.1155/2016/3029810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]