Abstract

Background:

A fixed-drug eruption (FDE) is a unique cutaneous adverse drug effect in the form of recurrent lesions at the same site after re-exposure to the offending agent.

Aim:

The aim of the study was to identify changes in trends in fixed drug eruptions with regard to causative drug or patient risk factors.

Methods:

Cases of FDEs encountered between March 2014 to May 2017 during routine pharmacovigilance activities were analyzed.

Results:

FDEs made up 8.4% of total adverse drug reactions and 11.1% of cutaneous reactions. Majority of the patients were adults between 18 and 45 years old. The average lag period between drug intake and appearance of FDE was 2.04 days. Commonly affected sites were extremities, lips, head and neck, and genitalia. Number of FDE lesions varied from 1 to > 6, with nearly half the patients (46%) presenting with a single lesion. Antimicrobials (80.6%) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (20.8%) were most frequent drugs implicated. Route of administration was oral for all causative drugs. History of an FDE was positive in 26 (50.2%) of the cases. Majority of the patients (21 out of 25 or 84%) whose lesions appeared within minutes to hours of suspected drug intake had a history of FDE. Furthermore, 66.7% of patients with multiple lesions had a history of FDE while only 34.8% of patients with a single lesion had such a history.

Conclusion:

FDEs are common cutaneous reactions with antimicrobials and anti-inflammatory agents, with increased likelihood of extensive and multiple lesions in patients with a history of FDE.

KEY WORDS: Cutaneous adverse drug reactions, drug rash, fixed-drug eruptions

What was known?

Fixed-drug eruption is known to occur more frequently with antimicrobials and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs than with other drugs. Extremities and genitalia are the most common sites involved, with different studies reporting different gender preferences.

Introduction

A fixed-drug eruption (FDE) is an immunological cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by sharply defined lichenoid lesion/s which occur/s at the same location every time there is exposure to the causative substance.[1] Exogenous agents are the only known cause of FDE. It does not occur spontaneously or following an infection. The skin lesion sometimes resolves when medication is discontinued, but it usually results in long-lasting or even permanent pigmentation.[1,2] Because of its characteristic features, FDE can be diagnosed with relative ease compared to other drug eruptions.

The number of diagnosed FDE cases is increasing steadily, due in part to increased awareness by physicians, but also because of increased use of drugs. Its incidence, from different reports, varies from 2.5% to a high of 22% of all patients with cutaneous adverse drug reactions (CADRs),[3] including data from the Indian population.[4] Fixed-drug eruptions occur in both sexes and in all age groups, including infants and the elderly, although a majority of cases are seen in the age range 20–40 years.

Materials and Methods

The study was carried out at a tertiary care hospital in central India, which was also an adverse drug reaction (ADR) Monitoring Centre under the Pharmacovigilance Programme of India since March 2014. All cases of FDE reported between March 2014 and May 2017 were analyzed for patient characteristics, type and number of FDE, and suspected drug. The aim of the study was to identify any change in trend in FDE with regard to causative drug or patient risk factors.

Results

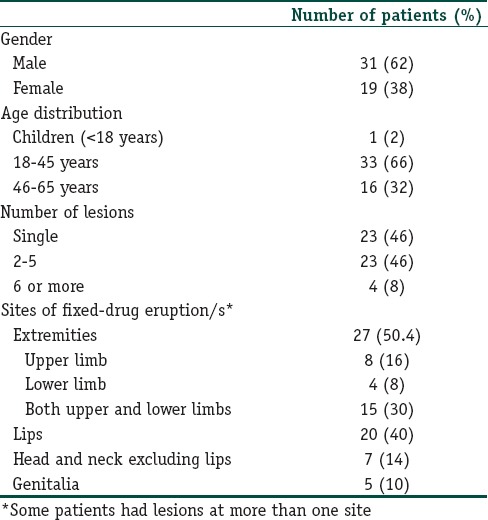

A total of 596 ADRs of which 451 (75.7%) CADRs were reported during the study period, i.e., March 2014 to May 2017. Among these, there were 50 patients (31 men and 19 women) with FDE, making it 8.4% of the total ADRs and 11.1% of CADRs. The mean age of the patients was 36.8 years, with a range from 7 to 62 years. Majority of the patients were adults between 18 and 45 years old [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with fixed-drug eruptions (n=50)

The lag period between intake of suspected drug and emergence of eruption ranged from 0 (lesions appeared on the same day) to 45 days, with an average lag period of 2.04 days. Twenty-one of the 25 patients who developed lesions on the same day had previous history of FDE, while one patient had a history of an unspecified allergic reaction to nimesulide. Only 3 patients with a lag period of onset of FDE of a few hours gave no previous history of FDE or any other drug allergy. History of an FDE in the past with the same (5), related (11) or unrelated (6) drug was positive in 26 (50.2%) of the cases. In four patients, drug responsible for FDE in the past was not known.

Commonly affected sites were extremities (27), lips (20), head and neck excluding the lips (7) and genitalia (5). Number of FDE lesions varied from 1 to >6, with 23 patients presenting with a single lesion and another 23 presenting with 2–5 lesions. Four patients had 6 or more lesions, three of whom were classified as extensive FDE. Of the 27 patients with 2 or more lesions, 18 had a history of FDE, while only 8 out of 23 patients with a single lesion had an FDE previously. Majority of the patients had well-defined hyperpigmented macules and/or plaques [Figures 1 and 2]. Bullous FDE was seen in 3 cases [Figures 3 and 4], while one patient had an overlap of plaques and bullous lesions, and one patient had ulcerated lesion on the lips. Out of the three patients who had extensive FDE, two were due to ciprofloxacin. One was a case of bullous FDE with vesicular lesions developing all over the body 20–30 min after ciprofloxacin. Another was a nonbullous FDE which appeared all over the body 5 days after taking ciprofloxacin. The third patient developed lesions over lips, scrotum, thighs, and both forearms after 2–3 h of taking a fixed-dose combination of acetaminophen 325 mg + aceclofenac 100 mg. Two out of the three patients with extensive FDE had a history of FDE.

Figure 1.

A sharply defined fixed-drug eruption on the trunk

Figure 2.

An old lesion showing hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, scarring, and scaling

Figure 3.

Bullous fixed-drug eruptions on dorsal aspect of foot

Figure 4.

Bilateral bullous fixed-drug eruptions on hands, with peeling of skin

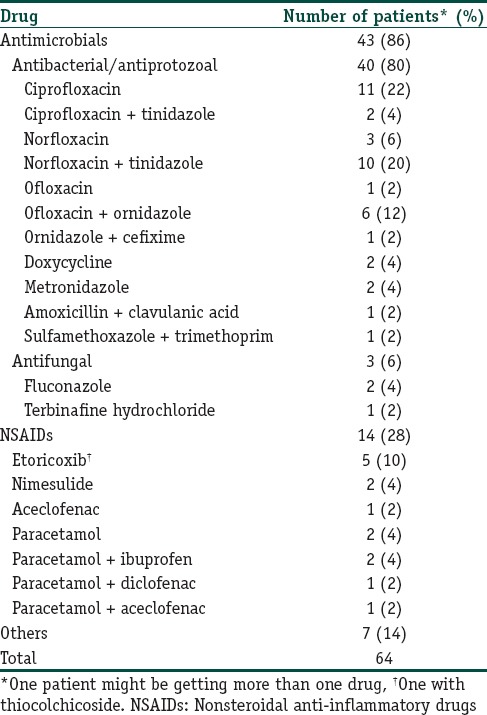

Antimicrobials (80.6%) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (20.8%) were the drugs implicated in a majority of patients. Four patients were receiving both antimicrobials and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at the time of developing the FDE. Among the antimicrobials, antibacterial agents or agents with dual antibacterial and antiprotozoal action (the nitroimidazoles) were most commonly used. Fluoroquinolones were the most common antibacterial involved, accounting for 34 (60.8%) of the FDE cases. In 18 of these patients, a nitroimidazole (metronidazole, tinidazole, or secnidazole) was prescribed along with a fluoroquinolone [Table 2]. Other drugs responsible for an FDE (not listed in table) were cetirizine, levocetirizine, loperamide, atropine-diphenoxylate, drotaverine, methylcobalamin-pregabalin, and a multivitamin-mineral preparation. An antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory agent was implicated in all patients with previous history of FDE [ Table 3].

Table 2.

Drugs implicated in fixed-drug eruptions

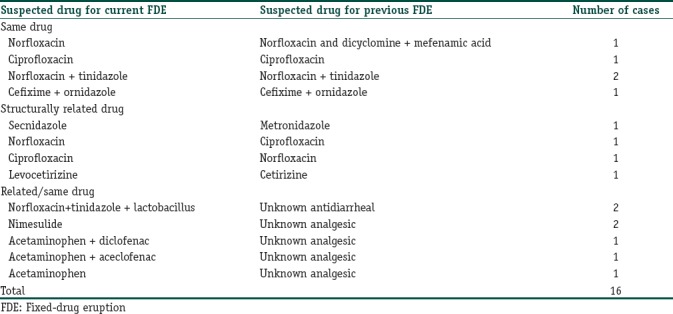

Table 3.

Drugs involved in patients with previous history of fixed-drug eruptions with same or related drugs

Route of administration was oral for all causative drugs.

The FDEs were treated by discontinuing the offending drug, topical corticosteroids, and oral antihistamines. More than half (50.4%) of the patients recovered within 10 days, while in 14 patients, the lesions took between 11 and 30 days to resolve. In all these patients, there was persistent hyperpigmentation of the affected site till last follow-up. In 7 patients, the lesions were resolving, while in 2 cases, the FDE was still continuing. Diagnosis of FDE was clinical in all the patients. There was unintentional oral rechallenge with ciprofloxacin, etoricoxib, or a multivitamin-mineral preparation in three patients by self administration (2 patients) or prescription (1 patient). In one patient with a single FDE on the shoulder with doxycycline, intentional oral rechallenge was carried out as it was decided to use doxycycline for a urinary tract infection. The patient was advised to take one-fourth of the original 100 mg dose but took the full 100 mg dose. Rechallenge was found to be positive in all four of these patients. Causality assessment was done by the Causality Assessment Committee of the in-house ADR Monitoring Center using the WHO-Uppsala monitoring center causality assessment criteria and was determined to be Certain in 44 cases, Probable in 2, and Possible in 4 cases with the suspected drugs. All cases were reported to the National Coordinating Center of Pharmacovigilance Programme of India.

Discussion

Although our cases numbered too few to give definitive trends, there was a predominance of men (31 men and 19 women). A slight male trend has been reported in some studies[5,3] while some analyzes report a female dominance.[6,7] According to some authors, FDEs account for 14%–22% of cutaneous drug reactions in children,[8,9] but in our study, there was only one child, 7 year old.

The most frequently affected sites in our series were the extremities (50.4%), followed by the lips (40%). Both these sites have been recognized as common sites of involvement in several studies.[1,2,6] We had only five cases with involvement of the genitalia.

Antimicrobials and NSAIDs are well-known triggers for an FDE[1,2,4] and were the common culprits in our series too. Among the antimicrobials, fluoroquinolones and nitroimidazoles were most commonly involved. This is in keeping with several other reports of FDE with these drugs as well as the increasing use of these drug groups in our country.[7,10,11] In 18 patients, these were given together, making it difficult to pinpoint any one drug as responsible. Sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, and doxycycline were earlier more frequently responsible for FDE, but with a decrease in their prescription rate, incidence of FDE due to them is likewise decreasing.[3] The other drugs implicated in our series, that is, fluconazole,[12] terbinafine, cetirizine[13,14] levocetirizine,[13,15,16,17] opioids,[18] and multivitamin-mineral preparations[19] have all been recognized as possible causes of FDE.

In a little over half the patients (50.2%), there was a history of an FDE. Many authors have reported a high proportion of recurrent FDEs.[11] In two patients, there was cross-reaction between ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin – that was an FDE due to norfloxacin in a patient with history of FDE with ciprofloxacin and vice versa. Similarly, there was cross-reaction between secnidazole-metronidazole and levocetirizine-cetirizine. Cross-reaction between fluoroquinolones, nitroimidazoles, fluoroquinolone-nitroimidazole combinations, and levocetirizine-cetirizine have been previously reported.[20,21,22,23] In 5 patients with FDE following an NSAID, there was a history of FDE with an analgesic/antipyretic though the exact drug was unknown. It could imply recurrence with same or a related drug. Similarly, in two patients with FDE due to an FDC-containing norfloxacin + tinidazole, there was history of FDE with an antidiarrheal drug.

Majority of the patients (21 out of 25 or 84%) whose lesions appeared within minutes to hours of suspected drug intake had history of FDE. Furthermore, 66.7% of patients with multiple lesions had a history of FDE while only 34.8% of patients with a single lesion had such a history. Although the number of cases was too small for statistical significance, it might be possible to expect that patients with a history of FDE were more likely to have a faster onset (lesions appeared within minutes to hours) as well as more number of lesions. Furthermore, two out of three patients with extensive FDE had history of FDE. The increase in number and severity of lesions on reexposure is related to the pathophysiology of FDE, which is still incompletely understood. Intraepidermal CD8+ T cells seem to play an important role in FDEs. These cells remain quiescent in a primed state in healed FDE lesions.[24] When a causative drug or a structurally related one is re-administered, the primed CD8+ T cells are activated to release interferon gamma and cytotoxic granules such as granzyme B and perforin. Mast cells also contribute to the activation of intraepidermal T cells by recruiting cell adhesion molecules on the surrounding keratinocytes, through the action of tumor necrosis factor alpha.[25] Cytokines and/or adhesion molecule-mediated recruitment of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and neutrophils may contribute to tissue damage in fully developed FDE lesions.

On a clinical front, the high percentage of patients with recurrent FDEs underlines the importance of recognizing an FDE as well as avoiding administration of same or structurally related drug to a patient who once developed an FDE. Since a patient may visit multiple health facilities and practitioners, the prescriber is often unaware of any history of FDE. Both patient as well as prescriber awareness is required to avoid inadvertent and unnecessary rechallenge with a causative drug.

Conclusion

Since an FDE cannot be reversed and the pigmentation often persists indefinitely, prevention is the key. This can be done by better awareness about the common causative drugs, the likelihood of recurrence with same or similar drugs, and use of alternatives where possible.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Pharmacovigilance programme of India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

What is new?

In our series, FDE was found to be more common in men. Although extremities were common sites involved, genitalia was involved in only 10% of the cases. Majority of the extensive and multiple lesions were seen in patients with a history of FDE. Lag period of appearance of FDE was shorter in patients with a history of FDE.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ghaziabad, National Coordinating Center, Pharmacovigilance Programme of India, for their support of adverse drug reaction monitoring activities, which had made this study possible.

References

- 1.Burgdorf WH, Plewig G, Wolff HH, Landthaler M, editors. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2009. Braun Falco's Dermatology; pp. 460–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. 8th ed. West Sussex (UK): Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology; pp. 75.28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Fixed drug eruption (FDE): Changing scenario of incriminating drugs. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:897–908. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel TK, Thakkar SH, Sharma D. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Indian population: A systematic review. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S76–86. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.146165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung JW, Cho SH, Kim KH, Min KU, Kang HR. Clinical features of fixed drug eruption at a tertiary hospital in Korea. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2014;6:415–20. doi: 10.4168/aair.2014.6.5.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavoussi H, Rezaei M, Derakhshandeh K, Moradi A, Ebrahimi A, Rashidian H, et al. Clinical features and drug characteristics of patients with generalized fixed drug eruption in the West of Iran (2005-2014) Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:236703. doi: 10.1155/2015/236703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saini R, Sharma B, Verma P, Rani S, Bhutani G. Fixed drug eruptions: Causing drugs, pattern of distribution and causality assessment in a leading tertiary care hospital. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:4356–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khaled A, Kharfi M, Ben Hamida M, El Fekih N, El Aidli S, Zeglaoui F, et al. Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in children. A series of 90 cases. Tunis Med. 2012;90:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma VK, Dhar S. Clinical pattern of cutaneous drug eruption among children and adolescents in North India. Pediatr Dermatol. 1995;12:178–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1995.tb00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta R. Fixed drug eruption due to ornidazole. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:635. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.143591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pai VV, Kikkeri NN, Athanikar SB, Shukla P, Bhandari P, Rai V, et al. Retrospective analysis of fixed drug eruptions among patients attending a tertiary care center in southern India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80:194. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakai N, Katoh N. Fixed drug eruption caused by fluconazole: A case report and mini-review of the literature. Allergol Int. 2013;62:139–41. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.12-LE-0464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta LK, Agarwal N, Khare AK, Mittal A. Fixed drug eruption to levocetirizine and cetirizine. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:411–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.135507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cravo M, Gonçalo M, Figueiredo A. Fixed drug eruption to cetirizine with positive lesional patch tests to the three piperazine derivatives. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:760–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kataria G, Saxena A, Sharma S. Levocetirizine induced fixed drug eruption: A rare case report. Int J Sci Study. 2014;2:228–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim MY, Jo EJ, Chang YS, Cho SH, Min KU, Kim SH, et al. A case of levocetirizine-induced fixed drug eruption and cross-reaction with piperazine derivatives. Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3:281–4. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.4.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.An I, Demir V, Ibiloglu I, Akdeniz S. Fixed drug eruption induced by levocetirizine. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:276–8. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_348_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matarredona J, Borrás Blasco J, Navarro-Ruiz A, Devesa P. Fixed drug eruption associated to loperamide. Med Clin (Barc) 2005;124:198–9. doi: 10.1157/13071489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gohel D. Fixed drug eruption due to multi-vitamin multi-mineral preparation. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pal A, Sen S, Das S, Biswas A, Tripathi SK. A case of self-treatment induced recurrent fixed drug eruptions associated with the use of different fixed dose combinations of fluoroquinolone-nitroimidazole. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39:584–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kameswari PD, Selvaraj N, Adhimoolam M. Fixed drug eruptions caused by cross-reactive quinolones. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2014;5:54–5. doi: 10.4103/0976-0105.134986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanmukhani J, Shah V, Baxi S, Tripathi C. Fixed drug eruption with ornidazole having cross-sensitivity to secnidazole but not to other nitro-imidazole compounds: A case report. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69:703–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jhaj R, Asati DP, Chaudhary D. Fixed drug eruption due to levocetirizine. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2016;7:109–11. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.184778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiohara T, Mizukawa Y. Fixed drug eruption: A disease mediated by self-inflicted responses of intraepidermal T cells. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:201–8. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizukawa Y, Yamazaki Y, Teraki Y, Hayakawa J, Hayakawa K, Nuriya H, et al. Direct evidence for interferon-gamma production by effector-memory-type intraepidermal T cells residing at an effector site of immunopathology in fixed drug eruption. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1337–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64410-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]