Abstract

An enantioselective cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) reaction to access tetrahydropyrans has been developed. This process combines in situ Lewis acid activation of a nucleophile in concert with the oxidative formation of a transient oxocarbenium electrophile, leading to a productive and highly enantioselective CDC. These advances represent one of the first successful applications of CDC for the enantioselective couplings of unfunctionalized ethers. This system provides efficient access to valuable THP motifs found in many natural products and bioactive small molecules.

Tetrahydropyrans (THPs) are key structural elements in numerous bioactive natural products and medicinally relevant compounds.1 Due to the prevalence of THPs, multiple stereoselective processes have been developed for their construction, including Prins cyclizations,2 hetero-Diels-Alder reactions,3 and intramolecular nucleophilic conjugate additions.4 Established methods to construct THPs in an enantioselective fashion typically focus on conjugate additions5 or activation by enamine/iminium intermediates,6 two approaches that are deployed extensively in total synthesis. Inspired by natural product targets of interest in our laboratory, as well as small molecules possessing intriguing biological activity, we envisioned a complementary and direct method for the enantioselective synthesis of substituted tetrahydropyran-4-ones. We have disclosed the use of β-hydroxy dioxinones as nucleophiles with aldehydes and isatins to undergo mild and stereoselective cyclizations in the presence of catalytic Lewis or Brønsted acids to access enantioenriched THPs.7 Our efforts in this area have enabled total syntheses of various natural products including exiguolide,8 neopeltolide,9 okilactomycin,10 and other naturally occurring compounds containing THPs.11 Conceptually, moving beyond preformed nucleophiles such as dioxinones to simple β-ketoester systems presents opportunities for enantiocontrol, most likely through two-point/chelate binding, but also requires different activation modes to operate simultaneously in a single reaction flask.

Cross-dehydrogenative coupling (CDC) reactions have emerged as powerful approaches to forge C—C bonds from inert C—H bonds.12 As a subset of C—H functionalization processes,13 CDC reactions are attractive because they do not require prefunctionalized starting materials, relying instead on oxidative activation followed by net loss of H2 to facilitate C—C bond formation. Specifically, 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ) a strong oxidizing agent, promotes the formation of stabilized carbocations by benzylic and allylic C—H bond activation, and subsequent C—C bond formation.14 Mechanistically, DDQ mediated CDC reactions proceed via single electron transfer to form stabilized radical cations, followed by hydrogen atom abstraction to form the electrophilic coupling partner (e.g., oxocarbenium ion, iminium ion). Floreancig has effectively demonstrated that DDQ activation can facilitate racemic access to carbocycles and heterocycles via the oxidation of allylic ethers.15 Although enantioselective CDC reactions have been reported during the last decade,16 there is a dearth of highly enantioselective CDC reactions using oxocarbenium ion electrophiles in contrast to a plethora of enantioselective CDC reactions using iminium electrophiles (Scheme 1b).17 A major challenge to this approach is successfully integrating strongly oxidative conditions for oxocarbenium ion formation (e.g., DDQ) with stereodefining catalysts necessary for nucleophile activation (e.g., chiral Lewis acids) to a) promote a productive reaction, and b) induce stereocontrol around a transient, highly reactive oxocarbenium ion. Herein we report an enantioselective CDC of β-ketoesters with oxocarbenium ions to access substituted tetrahydropyrans with high yields and enantioselectivity through a merged chiral Lewis acid/oxidation strategy (Scheme 1c).

Scheme 1.

CDC Processes and Reaction Design

We initiated our investigations of this chiral Lewis acid/oxidant process using β-ketoester substrate 1a and found that Cu(II)-bisoxazoline (BOX) complex L1•Cu(OTf)2 gave the desired product 2a as the sole diastereomer in 72% yield and 92:8 er at −70 °C (Scheme 2). Additional screening with chiral BOX ligands L2–L5 identified ligand L3 as optimal, furnishing 2a in 83% yield and 95:5 er upon further reaction dilution to 0.02 M. Finally, substrates bearing more sterically encumbered esters were screened with no improvement in observed stereoselectivity (see Supp. Info.).

Scheme 2. Ligand Screening for CDC Reactionsa.

aThe reactions were performed with 1a (0.2 mmol), L•Cu(OTf)2 (10 mol %), DDQ (0.26 mmol), Na2HPO4 (0.4 mmol), and MS 4Å (250 mg) in CH2Cl2 (0.04 M). Absolute configuration of 2a was determined based on X-ray crystal analysis of 2h.18 bYield of isolated product. cDetermined by chiral-phase SFC analysis.

After optimization the basic asymmetric CDC reaction with β-ketoester 1a, the general scope was explored (Table 1). When the aromatic ring on the cinnamyl ether was substituted with electron-donating groups at its para, meta, or ortho position, the reactions provided desirable tetrahydropyran-4-ones 2c–2g in high yields and stereoselectivity with exception of 2b. We observed that substrate 1b possessing a p-methoxycinnamyl group produced side products due to over-oxidation. Furthermore, reaction of 1b without a Cu(II) catalyst produced rac-2b in 70% yield in only 1 hour, suggesting the competitive background reaction of this highly reactive substrate also contributed to the observed reduction in stereoselectivity.

Table 1.

Substrate Scope of β-Keto Esters 1a

|

See Supp. Info. for reaction details. Er determined by chiral-phase SFC analysis. Products 2 were obtained with >20:1 dr (trans/cis).

Performed at −30 °C.

We then evaluated substrates substituted with electron-withdrawing groups at para, meta, and ortho positions. The reactions of 1h–1k provided desired products 2h–2k in moderate yields and high stereoselectivity. The results showed that high yields and stereoselectivity were observed for 1l and 1m containing naphthyl groups. The reaction of 1n containing a trisubstituted cinnamyl alkene afforded 2n in 87% yield and 97:3 er, while heteroaryl and conjugated ethers 1o–1q gave tetrahydropyran-4-ones 2o–2q in somewhat decreased yields and stereoselectivities. A survey of benzyl ethers revealed that only 4-methoxy-substituted substrates 1r–1t were capable of producing desired products 2r–2t with high stereoselectivity and moderate yield. Under the current conditions, we have not observed productive reactions using propargylic, unsubstituted allylic, alkyl, or ether substrates leading to tetrahydrofurans (i.e., 5 atom tether length). Instead, over-oxidation, resulting in 2,3-dihydropyran-4-one, or no oxidation is observed (see Supp. Info.). However, with this successful proof of concept, investigations with various oxidation methods and Lewis acids to engage an even larger range of substrate classes are ongoing.

Attempts to access enantioenriched tetrahydropyran-4-ones without the β-ketoester were unsuccessful, as enol acetate 3 provided racemic 4 in 68% yield (Scheme 3a). This observation supports the hypothesis that the β-ketoester is crucial for stereoselectivity by coordination with the Cu(II)/BOX catalyst. In an attempt to probe whether an enantioselective intermolecular CDC reaction was possible, cinnamyl methyl ether was exposed to methyl acetoacetate in the presence of L3•Cu(OTf)2 to afford 5 (Scheme 3b). Although the intermediate oxocarbenium ion could potentially undergo both 1,2-and 1,4-addition, the 1,2-addition adduct 5 was observed (as detected by NMR spectroscopy). Unfortunately, attempts to isolate 5 have been unsuccessful, due to facile elimination of the β-methoxy group to form enone 6 (2.7:1 E/Z mixture). Lastly, we evaluated α-methyl-β-ketoester 1z, which would forge a quaternary C-center (Scheme 3c). To our satisfaction, the reaction of 1z provided the desired (2R,3R)-7 in 65% yield (>20:1 dr, 96:4 er)23 which provides a roadmap for future intermolecular asymmetric CDC reactions.

Scheme 3.

CDC Reaction Extension

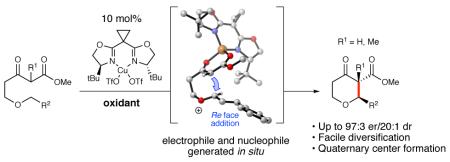

The stereochemical model of the reaction with 1a, Cu(II)/BOX and DDQ is based on a reported X-ray crystal structure of [L1•Cu(H2O)2](SbF6)2 by replacement of H2O ligands with the oxocarbenium ion of 1a (Figure 1).19 With the oxidized substrate bound to the Cu(II) center via bidentate chelation, the bulky tert-butyl group of the L3•Cu(II) complex shields the top face of the bound substrate (Si face) which in turn places the transient oxocarbenium ion below. During the reaction, the metal-bound enol(ate) adds to the Re face of the oxocarbenium ion via a pseudo chair-like conformation to provide product 2a with S configuration at the C1′ position, consistent with observed stereochemistry. This model also supports the observed relative C1′-C2′ trans relationship of the products.

Figure 1.

Stereochemical induction model with 1a/DDQ intermediate (see Supp. Info. for details)

A practical advantage of this strategy is the ease of synthetically elaborating these β-keto esters (Scheme 4). Conventional heating in DMF/H2O provided the decarboxylated product 4 in 77% yield, where methylation of 2a gave 3,3-disubstituted tetrahydropyran-4-one (2R,3S)-7 in excellent yield with 13:1 dr.23 Exposure of β-ketoesters 2a or 7 to L-selectride provided the corresponding tetrahydropyran-4-ol 8 or 9, while LiAlH4 reduction of 7 furnished diol 10.20 Functionalization of the 6-position of the 7 has also been demonstrated. First, cyclic enone 11 was prepared via dehydrogenation using 1 atm of O2 in the presence of Pd(TFA)2 in DMSO.21 Rh(I)-catalyzed 1,4-addition of phenylboronic acid produced 12,22 and conjugate addition of an alkyl cuprate provided 13 as the trans diastereomers in both reactions.20,23 Lastly, a Mukaiyama-Michael addition proceeded to afford 14 with 10:1 diasteromeric ratio.23,24 Notably, while many synthetic methods exist for cis-2,6-tetrahydropyran structures,25 there are far fewer preparations for trans-2,6-tetrahydropyrans.26

Scheme 4. Transformations of 2a.

aConditions: (a) DMF/H2O, 130 °C, 77% (b) MeI, NaH, 97%, 13:1 dr (c) L-selectride, 64% for 8, 71% for 9 (d) LiAlH4, 62% (e) Pd(TFA)2, O2, 67% (f) Rh(cod)2BF4, PhB(OH)2, 75%, 20:1 dr (g) nBu2CuLi, TMSCl, 76%, 20:1 dr (h) 15, InCl3, 93%, 10:1 dr

To substitute DDQ as a reagent, we investigated complementary oxidation processes to form the oxocarbenium ion. A recent report of photoredox catalysis being used to generate oxocarbenium ions27 inspired us to leverage this approach and trap the oxocarbenium ion with our tethered carbon nucleophile. Gratifyingly, the use of Sc(OTf)3, Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6, blue LEDs, and bromochloroform provided access to rac-2a in 90% yield (Scheme 5). To date, these photoredox conditions are not yet compatible with various chiral ligands to induce enantioselectivity.28

Scheme 5.

Photoredox-Catalyzed CDC Reaction

In summary, a chiral Lewis acid-catalyzed intramolecular cross-dehydrogenative coupling of β-ketoesters has been developed. This oxidative process utilizes unfunctionalized starting materials to provide chiral 2-substituted tetrahydropyrans with excellent yields and stereoselectivity. The in situ generation of both nucleophilic and electrophilic partners specifically provides new opportunities for enantioselective oxocarbenium ion-driven reactions and CDC processes in general. Investigations in our laboratory towards leveraging this chiral Lewis acid/oxidation system with new substrate classes as well as the use of visible light mediated oxidation in asymmetric transformations are currently underway.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support for this work has been provided by the NCI (R01 CA126827) and the American Cancer Society (Research Scholar award 09-016-01 CDD). RCB acknowledges financial support from the NIGMS (T32GM105538). The authors thank Charlotte Stern (Northwestern) for as-sistance with X-ray crystallography.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supp. Info. Experimental procedures and spectroscopic, and crystallographic details. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1) (a). Boivin TLB Tetrahedron 1987. 43 3309–3362 [Google Scholar]; (b) Marmsäter FP West FG Chem. Eur. J 2002. 8 4346–4353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a). Adams DR Bhatnagar SP Synthesis 1977. 1977 661–672 [Google Scholar]; (b) Cloninger MJ Overman LE J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999. 121 1092–1093 [Google Scholar]; (c) Jasti R Vitale J Rychnovsky SD J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004. 126 9904–9905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3) (a). Dossetter AG Jamison TF Jacobsen EN Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1999. 38 2398–2400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Heravi MM Ahmadi T Ghavidel M Heidari B Hamidi H RSC Advances 2015. 5 101999–102075 [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a). Clarke PA Santos S Eur. J. Org. Chem 2006. 2006 2045–2053 [Google Scholar]; (b) Larrosa I Romea P Urpí F Tetrahedron 2008. 64 2683–2723 [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a). Nising CF Brase S Chem. Soc. Rev 2008. 37 1218–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nising CF Brase S Chem. Soc. Rev 2012. 41 988–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6) (a). Vetica F Chauhan P Dochain S Enders D Chem. Soc. Rev 2017. 46 1661–1674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7) (a). Betori RC Miller ER Scheidt KA Adv. Synth. Catal 2017. 359 1131–1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Morris WJ Custar DW Scheidt KA Org. Lett 2005. 7 1113–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang J Crane EA Scheidt KA Org. Lett 2011. 13 3086–3089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8). Crane EA Zabawa TP Farmer RL Scheidt KA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011. 50 9112–9115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a). Custar DW Zabawa TP Hines J Crews CM Scheidt KA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009. 131 12406–12414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Custar DW Zabawa TP Scheidt KA J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008. 130 804–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10). Tenenbaum JM Morris WJ Custar DW Scheidt KA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011. 50 5892–5895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11) (a). Lee K Kim H Hong J Org. Lett 2011. 13 2722–2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee K Kim H Hong J Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012. 51 5735–5738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Han X Peh G Floreancig PE Eur. J. Org. Chem 2013. 2013 1193–1208 [Google Scholar]; (d) Nasir NM Ermanis K Clarke PA Org. Biomol. Chem 2014. 12 3323–3335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12) (a). Li C-J Acc. Chem. Res 2009. 42 335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yeung CS Dong VM Chem. Rev 2011. 111 1215–1292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Girard SA Knauber T Li C-J Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014. 53 74–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13) (a). Yi H Zhang G Wang H Huang Z Wang J Singh AK Lei A Chem. Rev 2017. 117 9016–9085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davies HML Morton D J. Org. Chem 2016. 81 343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gensch T Hopkinson MN Glorius F Wencel-Delord J Chem. Soc. Rev 2016. 45 2900–2936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Arockiam PB Bruneau C Dixneuf PH Chem. Rev 2012. 112 5879–5918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Colby DA Tsai AS Bergman RG Ellman JA Acc. Chem. Res 2012. 45 814–825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gutekunst WR Baran PS Chem. Soc. Rev 2011. 40 1976–1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lyons TW Sanford MS Chem. Rev 2010. 110 1147–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14) (a). Ying B-P Trogden BG Kohlman DT Liang SX Xu Y-C Org. Lett 2004. 6 1523–1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Y Li C-J Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006. 45 1949–1952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15) (a). Brizgys GJ Jung HH Floreancig PE Chem. Sci 2012. 3 438–442 [Google Scholar]; (b) Cui Y Floreancig PE Org. Lett 2012. 14 1720–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu L Floreancig PE Org. Lett 2009. 11 3152–3155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Liu L Floreancig PE Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010. 49 5894–5897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tu W Liu L Floreancig PE Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008. 47 4184–4187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16) (a). Guo C Song J Luo S-W Gong L-Z Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010. 49 5558–5562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang G Zhang Y Wang R Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011. 50 10429–10432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhang J Tiwari B Xing C Chen X Chi YR Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012. 51 3649–3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan Y Yuan W Gong L Meggers E Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015. 54 13045–13048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sun S Li C Floreancig PE Lou H Liu L Org. Lett 2015. 17 1684–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Xie Z Liu X Liu L Org. Lett 2016. 18 2982–2985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Xie Z Zan X Sun S Pan X Liu L Org. Lett 2016. 18 3944–3947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yang Q Zhang L Ye C Luo S Wu L-Z Tung C-H Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017. 56 3694–3698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17) (a). Cui Y Villafane LA Clausen DJ Floreancig PE Tetrahedron 2013. 69 7618–7626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Meng Z Sun S Yuan H Lou H Liu L Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014. 53 543–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wan M Sun S Li Y Liu L Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017. 56 5116–5120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lu R, Li Y, Zhao J, Li J, Wang S, Liu L. Chem. Commun. 2018 doi: 10.1039/C8CC01276H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).CCDC 1817530 (2h) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. This data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystalographic Data Centre.

- (19) (a). Evans DA Johnson JS Olhava EJ J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000. 122 1635–1649 [Google Scholar]; (b) Evans DA Scheidt KA Johnston JN Willis MC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001. 123 4480–4491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20). Clarke PA Sellars PB Nasir NM Org. Biomol. Chem 2015. 13 4743–4750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21). Diao T Stahl SS J. Am. Chem. Soc 2011. 133 14566–14569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22) (a). Kumaraswamy G Ramakrishna G Naresh P Jagadeesh B Sridhar B J. Org. Chem 2009. 74 8468–8471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ramnauth J Poulin O Bratovanov SS Rakhit S Maddaford SP Org. Lett 2001. 3 2571–2573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23) (a).The stereochemistry of the products was determined by NOESY experiments. See Figure S1–S4 for details.

- (24). Chua S-S Alni A Jocelyn Chan L-T Yamane M Loh T-P Tetrahedron 2011. 67 5079–5082 [Google Scholar]

- (25) (a). Carpenter J Northrup AB Chung d. Wiener JJM Kim S-G MacMillan DWC Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2008. 47 3568–3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith AB Tomioka T Risatti CA Sperry JB Sfouggatakis C Org. Lett 2008. 10 4359–4362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Olier C Kaafarani M Gastaldi S Bertrand MP Tetrahedron 2010. 66 413–445 [Google Scholar]

- (26) (a). Ferrié L Reymond S Capdevielle P Cossy J Org. Lett 2007. 9 2461–2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brazeau J-F Guilbault A-A Kochuparampil J Mochirian P Guindon Y Org. Lett 2010. 12 36–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27). Tucker JW Narayanam JMR Shah PS Stephenson CR J. Chem. Commun 2011. 47 5040–5042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.