Changes in secondary cell wall cellulose synthase stoichiometry coincide with changes in cellulose microfibril diameter in aspen.

Abstract

Cellulose is synthesized at the plasma membrane by cellulose synthase complexes (CSCs) containing cellulose synthases (CESAs). Genetic analysis and CESA isoform quantification indicate that cellulose in the secondary cell walls of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) is synthesized by isoforms CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 in equimolar amounts. Here, we used quantitative proteomics to investigate whether the CSC model based on Arabidopsis secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry can be applied to the angiosperm tree aspen (Populus tremula) and the gymnosperm tree Norway spruce (Picea abies). In the developing xylem of aspen, the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry was 3:2:1 for PtCESA8a/b:PtCESA4:PtCESA7a/b, while in Norway spruce, the stoichiometry was 1:1:1, as observed previously in Arabidopsis. Furthermore, in aspen tension wood, the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry changed to 8:3:1 for PtCESA8a/b:PtCESA4:PtCESA7a/b. PtCESA8b represented 73% of the total secondary cell wall CESA pool, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis of CESA transcripts in cryosectioned tension wood revealed increased PtCESA8b expression during the formation of the cellulose-enriched gelatinous layer, while the transcripts of PtCESA4, PtCESA7a/b, and PtCESA8a decreased. A wide-angle x-ray scattering analysis showed that the shift in CESA stoichiometry in tension wood coincided with an increase in crystalline cellulose microfibril diameter, suggesting that the CSC CESA composition influences microfibril properties. The aspen CESA stoichiometry results raise the possibility of alternative CSC models and suggest that homomeric PtCESA8b complexes are responsible for cellulose biosynthesis in the gelatinous layer in tension wood.

The wood of trees provides a renewable raw material resource of high economic value. The main component in wood is cellulose, which is produced as cellulose microfibrils (CMFs) consisting of fibrillar crystalline aggregates of β-1,4-glucans. The majority of the cellulosic biomass resides in the secondary walls of xylem cells, where the CMFs are embedded in a matrix of hemicelluloses and lignin. The CMFs are synthesized and laid down in an organized and controlled pattern contributing to the unique mechanical properties of the xylem cell walls and wood in general (Gibson, 2012). Hence, it is of both basic and applied interest to understand the biosynthetic machinery responsible for CMF formation in the differentiating xylem of trees.

Experimental work, mainly using nonwoody species, shows that the β-1,4-glucan chains of CMFs are synthesized at the plasma membrane by cellulose synthases (CESAs). Plant genomes code for multiple CESA isoforms classified into primary and secondary cell wall CESAs (Somerville, 2006; McFarlane et al., 2014). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), primary cell wall cellulose is synthesized by CESA1, CESA3, and one of the CESA6-related proteins (CESA2, CESA5, CESA6, or CESA9), while secondary cell walls are synthesized by CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 (Taylor et al., 2003; Desprez et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007). The plasma membrane-localized CESAs assemble into the catalytic core of the cellulose synthase complex (CSC). CSCs show 6-fold rosette-like symmetry when observed in electron micrographs of freeze-fractured plasma membranes. CSC rosettes were first observed in the plasma membranes of maize (Zea mays) and loblolly pine (Pinus taeda; Mueller and Brown, 1980) and have since then been observed in several other plant species, including the differentiating xylem of the eucalyptus tree (Eucalyptus tereticornis; Fujino, 1998). Evidence that the CSC rosettes contain CESAs is provided by the identification of the Arabidopsis radially swollen1 (rsw1) locus coding for a temperature-sensitive CESA1 isoform (Arioli et al., 1998). The CSCs in the plasma membrane of rsw1 mutants appear disorganized and reduced in number under restrictive temperatures. Further evidence for the presence of CESAs in the CSCs has been obtained from azuki bean (Vigna angularis) by gold immunolabeling of plasma membrane rosettes with a CESA antibody (Kimura et al., 1999).

Arabidopsis null mutants lacking CESA4, CESA7, or CESA8 are all phenotypically similar and have comparable reduction in cellulose content and xylem secondary cell wall thickness (Turner and Somerville, 1997; Taylor et al., 2003). Furthermore, double and triple mutants of secondary cell wall CESAs have similar cellulose content to the single mutants (Kumar and Turner, 2015). These observations support a model suggesting that CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 coexist in the same CSC. This model is further supported by experiments showing that an antibody against one of the CESAs coimmunoprecipitates the other two secondary cell wall CESAs (Taylor et al., 2003). Similar results have been obtained for the primary cell wall CESAs in Arabidopsis (Desprez et al., 2007; Persson et al., 2007) and secondary cell wall CESAs in Populus deltoides × Populus trichocarpa xylem extracts (Song et al., 2010). The latter observation indicated that secondary cell wall CSCs in Populus spp. also consist of CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 heteromers.

The initial CSC models contain 36 CESA subunits per rosette, with six CESAs in each rosette lobe (Herth, 1983; Scheible et al., 2001) and a 3:2:1 stoichiometry of the three CESA isoforms (Doblin et al., 2002; Ding and Himmel, 2006). The 3:2:1 stoichiometry model is derived from the hypothesis that not all of the three CESA isoforms form direct protein-protein contacts with each other. Instead, the CESA isoform present in a single copy interacts only with the isoform present in three copies and the isoform present in two copies per hexamer is the only one that can interact with the same isoform from a neighboring hexamer (Doblin et al., 2002; Ding and Himmel, 2006). However, whether such CESA contact rules constrain CSC assembly has not been established experimentally. Recently, the 3:2:1 stoichiometry model has been challenged by experimental evidence from Arabidopsis indicating that both the primary and secondary cell wall CSC rosettes consist of equimolar amounts of the respective CESA isoforms (Gonneau et al., 2014; Hill et al., 2014).

The diameter of CMFs and the number of glucan chains per CMF relate to the number of catalytically active CESAs in one rosette. Recent studies using NMR spectroscopy, wide-angle x-ray scattering (WAXS), small-angle neutron scattering, and computer modeling favor models containing 18 glucan chains in mung bean (Vigna radiata) primary cell walls and 24 glucan chains per CMF in celery (Apium graveolens) collenchyma primary walls and early wood of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis; Fernandes et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2013). Combined with the finding that Arabidopsis CESAs exist in 1:1:1 stoichiometry, and assuming that all CESAs are active, led both Gonneau et al. (2014) and Hill et al. (2014) to conclude that a 6 × 3 CESA complex producing 18 glucan chains is most likely. However, since CMF dimensions between higher plants are not constant (Jarvis, 2018), this model may not apply to all species. It is also clear that the CMF diameter can differ between cell types, as exemplified in tension wood fibers of angiosperm trees (Mueller and Sugiyama, 2006). Tension wood contains wood fibers with an inner cell wall layer of highly enriched crystalline cellulose, called the gelatinous or G-layer (Felten and Sundberg, 2013). X-ray diffraction studies showed that the CMFs in the G-layer of Populus maximowiczii are thicker than those in the S2 layer of fiber walls (Mueller and Sugiyama, 2006). Mueller and Sugiyama (2006) suggested that these differences in CMF properties between S2- and G-layers may be derived from differences in cellulose biosynthesis and/or differences in microfibril aggregation due to the reduction of other matrix polymers in the G-layer.

In this study, we determined the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry in Arabidopsis inflorescence stems and the differentiating xylem of aspen (Populus tremula) and Norway spruce (Picea abies). The Populus spp. genome contains 17 CESA genes, five of which encode orthologs of the Arabidopsis secondary cell wall CESAs (Kumar et al., 2009). Arabidopsis CESA4 has one ortholog in Populus (PtCESA4), whereas AtCESA7 and AtCESA8 are represented by two gene models named PtCESA7a/PtCESA7b and PtCESA8a/PtCESA8b, respectively. The PtCESA7a/b and PtCESA8a/b gene pairs result from the Populus spp. genome duplication approximately 65 million years ago (Tuskan et al., 2006; Takata and Taniguchi, 2015). PtCESA4 also was probably duplicated, but the second copy was later lost during a chromosome rearrangement event (Takata and Taniguchi, 2015). The Norway spruce genome codes for 10 CESAs, and phylogenetic comparison of Arabidopsis, aspen, and spruce CESAs identified a single ortholog of each secondary cell wall CESA in the spruce genome, denoted PaCESA4, PaCESA7, and PaCESA8 (Jokipii-Lukkari et al., 2017). Gene expression profiling of differentiating spruce xylem showed increased expression of these orthologs coinciding with secondary cell wall formation, further supporting their classification as secondary cell wall CESAs (Jokipii-Lukkari et al., 2017).

The stoichiometry of the aspen and spruce secondary cell wall CESAs was investigated by mass spectrometry-based proteomics and multiple reaction monitoring (MRM). MRM has emerged as a powerful technique for the sensitive and accurate quantification of proteins. In a quantitative MRM proteomics experiment, known amounts of stable isotope-labeled reference peptides are added into the sample, and the quantification is achieved by comparing the mass spectrometry intensities of the reference with endogenous peptide generated upon the proteolytic cleavage of the target protein (Brönstrup, 2004). We discovered that the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry in the differentiating aspen xylem differs from that of Arabidopsis and Norway spruce. Furthermore, the aspen tension wood CESA stoichiometry was different from that of normal aspen wood. Since the CMF diameter is different in tension wood, this suggests that it can be influenced by the stoichiometry and type of CESAs.

RESULTS

Optimization of CESA Extraction from Differentiating Xylem

CSCs are known to be unstable during protein extraction (Brown et al., 2012). To minimize CESA and CSC degradation and loss during sample preparation, we developed a rapid extraction method where protein digestion was conducted directly on the pellet remaining after a 20-min, 20,000g centrifugation of the xylem extract. To investigate the distribution of CESAs between the pellet and supernatant, the samples were digested with trypsin and analyzed using MRM. The majority of the CESA-derived peptides were found in the pellet fraction, whereas the supernatant contained levels too low for reliable quantification (data not shown). Thus, the subsequent experiments only used the pellet fraction for CESA digestion and stoichiometry determination. To quantify CESAs and to investigate secondary cell wall CESA composition in different species, we designed a quantitative liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) assay using MRM based on CESA isoform-specific standard peptides from Arabidopsis, aspen, and Norway spruce.

Standard Peptide Selection for Arabidopsis, Norway Spruce, and Aspen CESA Quantification

Secondary cell wall CESA isoforms and corresponding protein identifiers from Arabidopsis, Norway spruce, and aspen are listed in Table I. We selected for species and CESA isoform-specific peptides for quantification experimentally. We analyzed digested protein extracts on a Synapt G2 mass spectrometer in full scan mode and screened the data for CESA-derived peptides. All detected peptides derived from CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 from each species are listed in Supplemental Table S1. We selected six peptides from Arabidopsis, 12 from aspen, and 10 from spruce to the following rules: (1) unique peptide sequence; (2) peptide length between eight and 25 amino acids; (3) no peptides with potential acetylation, phosphorylation, or N-glycosylation sites; (4) no peptides with two consecutive K or R at either end (i.e. KK, KR, RK, RR) or one amino acid between two consecutive K or R (i.e. K/R-X-K/R) to avoid trypsin miscleavage; and (5) no peptides with N-terminal Q, which transforms into pyro-Glu under acidic conditions. Peptides containing M or C were not selected against, but all Cys residues were carbamidomethylated. Six of the selected standard peptides were isotopically labeled for internal normalization (Table I). Protein identifiers, peptide sequences, positions of the stable isotopic labeling, dwell times, transitions monitored, retention times, and cone voltages are shown in Supplemental Data Set S1.

Table I. Arabidopsis, aspen, and Norway spruce secondary cell wall CESA isoforms and the corresponding peptides used for quantification.

Underlined amino acids in boldface were isotope labeled (13C and 15N). Peptide number relates to the peptide location shown in Figure 1A. Potra stands for P. tremula and Potri stands for P. trichocarpa.

| Species | Protein Name and Accession No. | Peptide Sequence | Peptide No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | CESA4 | APEFYFSEK | 4 |

| AT5G44030.1 | FDGIDLNDR | 15 | |

| CESA7 | ATDDDDFGELYAFK | 24 | |

| AT5G17420.1 | FDGIDTNDR | 16 | |

| CESA8 | TADDLEFGELYIVK | 25 | |

| AT4G18780.1 | DIEGNELPR | 5 | |

| Aspen | CESA4 | APEFYFTQK | 9 |

| Potra002707g19806 (Potri.002G257900) | SADDAEFGELYLFK | 26 | |

| CESA7a | APEFYFALK | 7 | |

| Potra002910g20286 (Potri.006G181900) | EPPLVTGNTILSILAMDYPVEK | 6 | |

| CESA7a/b | VHPYPVSEPGSAR | 3 | |

| CESA7b | FDGIDTHDR | 12 | |

| Potra003935g23615 (Potri.018G103900) | APEFYFTLK | 8 | |

| CESA8a | AADDTEFGELYMVK | 27 | |

| Potra004051g24387(Potri.011G069600) | SMLISQLSFEK | 18 | |

| CESA8a/b | DIEGNELPR | 10 | |

| CESA8b | VSAVLTNAPYILNVDCDHYVNNSK | ||

| Potra000473g02869 (Potri.004G059600) | ESGNQSTMASHLNDSQDVGIHAR | 2 | |

| Spruce | CESA4 (comp89823_c0_seq1) | SVYCMPTRPAFK | 19 |

| WALGSIEIFMSR | 20 | ||

| VLAGVDTNFTVTAK | 23 | ||

| FEGPILQQCGVDC | 28 | ||

| GNAFDTTPR | 1 | ||

| APDFYFSLK | 13 | ||

| CESA7 (comp89823_c0_seq2) | APEIYFSQK | 14 | |

| ASDDGEFGELYAFK | 22 | ||

| CESA8 (comp89823_c0_seq3) | VSAVLTNAPYLLNLDCDHYVNNSK | 17 | |

| SSDDNEFGELYAFK | 21 |

Optimization of CESA Digestion

There are several sources of variation that can introduce bias in quantitative proteomics, including sample preparation, mass spectrometric acquisition, and spectral data interpretation. Incomplete protein digestion and labile amino acid residues of peptides are generally believed to be the major factors that contribute to inaccurate protein quantification with LC-MS (Brönstrup, 2004; Chiva et al., 2014). Trypsin has a lower digestion efficiency at K compared with R, especially in the presence of acidic amino acids D and E next to the digestion pocket. The miscleavages at K can be reduced greatly by using Lys C as the second digestion enzyme (Glatter et al., 2012; Chiva et al., 2014). Hence, to maximize CESA digestion, we used a Lys C/trypsin mixture, which has a higher efficiency of sample digestion than trypsin alone (Saveliev et al., 2013). We added 1% sodium deoxycholate (SDC) to both the extraction buffer and the digestion buffer to facilitate the solubilization of CESAs. SDC improves membrane protein digestion and can be removed through acid precipitation to avoid interference with the subsequent LC-MS analysis (Erde et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2015).

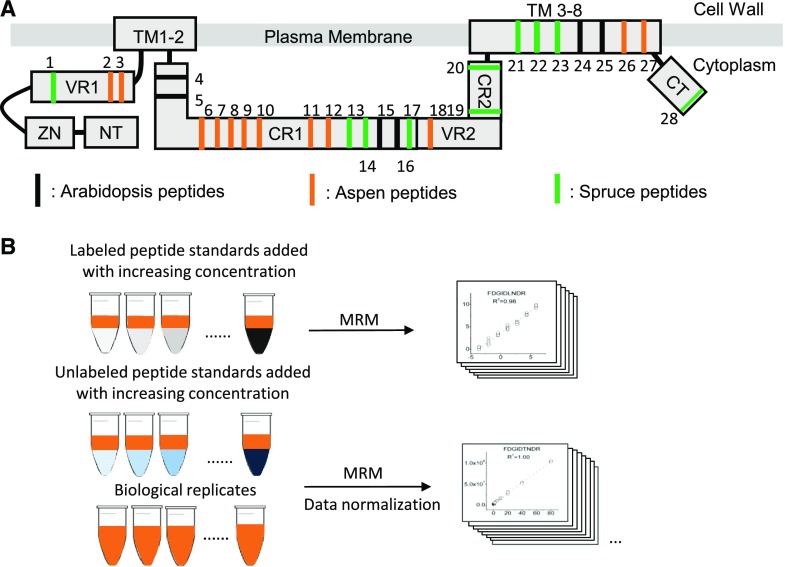

Another potential source of experimental variation is derived from differences in peptide release rates upon protein digestion. Peptides also can decay after digestion, leading to inaccuracies in quantification (Shuford et al., 2012). To determine CESA peptide production and decay rates upon Lys C/trypsin digestion, we carried out a time-course experiment where the digestions were quenched at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and 18 h. We quantified peptides through MRM and plotted the peak areas against the digestion time (Supplemental Fig. S1). A total of 27 CESA peptides were identified and classified into three groups named fast, slow, and very slow based on the digestion release rates (Supplemental Fig. S1). All of the 27 peptides were stable during the time course. The optimal digestion time was 10 h, based on complete release and minimal degradation of fast and slow peptides. The peptides chosen for quantification are listed in Table I, and their locations in relation to the CESA membrane topology are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Selected peptides and schematic of peptide quantification. A, Locations of the CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 peptides in Arabidopsis (black), aspen (red), and Norway spruce (green). Transmembrane domain regions (TM), N terminus (NT), zinc RING-type finger (ZN), variable region 1 (VR1), conserved region 1 (CR1), variable region 2 (VR2), conserved region 2 (CR2), and C terminus (CT) are indicated. The number assigned to each peptide also is shown in Table I. B, Workflow of the CESA mass spectrometry analysis.

Accuracy and Linearity of CESA Quantification

The precise quantification of target proteins through MRM experiments is based on the mass signal intensities of the target peptide and the internal standard. In most cases, synthesizing a stable isotope-labeled peptide for each target peptide is the most straightforward way to effectively overcome problems of fluctuations in mass signal intensity, which depends on peptide sequence, the matrix, and several experimental factors that cannot be controlled precisely. These factors become particularly problematic when many diverse samples are analyzed (Lange et al., 2008). Another alternative is label-free MRM quantification, which can be used when the samples are closely related in background and protein composition and the sample processing is well controlled (Lange et al., 2008).

The method we used in this study was a combination of label-free MRM and labeled MRM, as outlined in Figure 1B. Since the secondary cell wall CESAs are closely related between the three species, the 27 selected standard peptides could be classified into groups based on sequence similarity. At least one peptide from each group (six peptides in total) was isotopically labeled. To control for the mass signal fluctuations, these six peptides were used as normalization peptides before the generation of calibration curves and quantification of the other 21 peptides (for details of normalization, see “Materials and Methods”). By normalizing the average of the peak area of the six peptides to the same level, the relative sd of the injections was reduced greatly (data not shown) and the signal intensity difference originating from sample matrix change was largely overcome (Supplemental Figs. S2–S4).

The linearity of the standard curves for the 27 peptides was between 0.94 and 1 for all peptides apart from EPPLVTGNTILSILAMDYPVEK, which had R2 = 0.8 (Supplemental Fig. S5). An extra quality assessment (QA) sample was prepared by spiking in the target peptides at known concentration to the sample matrix. QA was then performed before quantification by comparing the difference between the true concentration and the calculated concentration. The results for QA are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Two aspen peptides, VHPYPVSEPGSAR (PtCESA7a/b) and EPPLVTGNTILSILAMDYPVEK (PtCESA7b), exhibited low recovery rates of 34.5% and 41.7% and very high relative standard deviations (RSDs) of 70.4% and 41.7%, respectively. Thus, these peptides were not used for quantification. The recovery of other peptides ranged from 91.4% to 119%, with most of the RSDs less than 10%, indicating good data quality (Mohammed et al., 2015).

Selection of Peptides for CESA Quantification

The peptides selected for CESA quantification are summarized in Table I. Peptides were excluded because of digestion problems, potential S-acetylation sites (FEGPILQQCGVDC), and large RSDs. The digestion time optimization experiment identified differences in trypsin digestion speed between peptides (Supplemental Fig. S1). Twelve of the 27 peptides belonged to the slow production or very slow production category peptides, indicating a low digestion efficiency. These peptides likely reside in the predicted transmembrane domains of CESAs, which can cause problems in digestion (Fig. 1A). The presence of multiple Glu or Asp acidic residues (E or D) near the cleavage site also can contribute to the relatively slow cleavage of these peptides (Šlechtová et al., 2015). Thus, the slow production peptides were excluded from further analysis, and the peptides showing the highest digestion efficiency were used for the CESA quantification.

Secondary Cell Wall CESA Stoichiometry in Aspen Differs from That in Arabidopsis and Norway Spruce

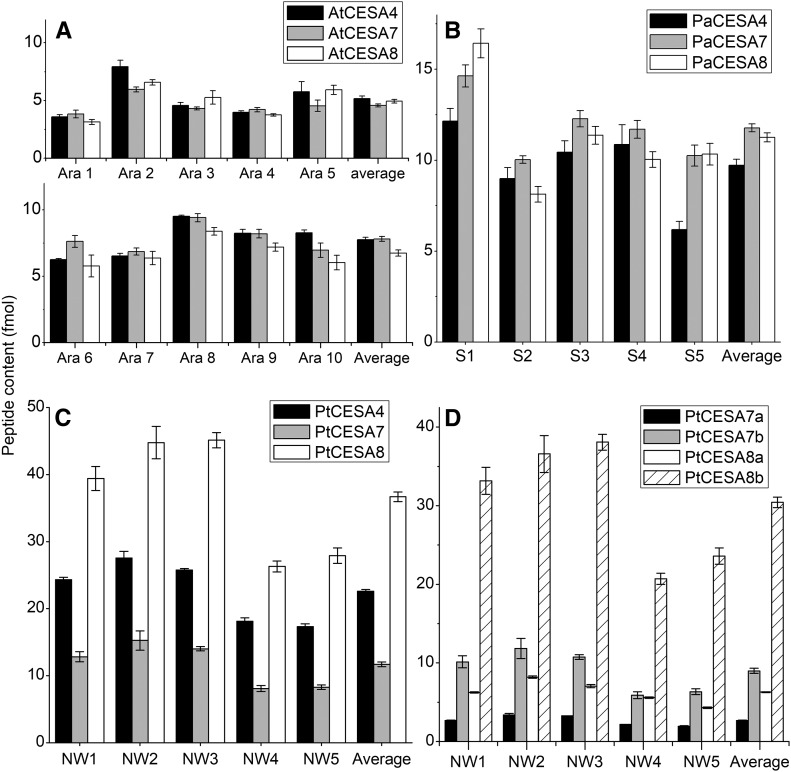

To compare the MRM CESA quantification method with the published Arabidopsis secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry results, we analyzed 6-week-old Arabidopsis stems using the extraction protocol by Hill et al. (2014) as well as the extraction method developed in this study. Peptides with the highest concentrations were chosen to represent the concentration of corresponding proteins. Both extraction methods gave similar results, supporting the 1:1:1 ratio of the secondary cell wall CESA CSC model in accordance with the previous findings (Hill et al., 2014; Fig. 2A; Supplemental Tables S3 and S4). Also, developing xylem of Norway spruce exhibited an equimolar stoichiometry of CESAs (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table S5). In a marked difference from Arabidopsis and Norway spruce, the differentiating xylem of aspen contained PtCESA4, PtCESA7a/b, and PtCESA8a/b at an average ratio of 2:1:3 (Fig. 2C; Supplemental Table S6). Quantification of the duplicate PtCESA7a/b and PtCESA8a/b isoforms showed that there is more PtCESA7a than PtCESA7b and more PtCESA8b than PtCESA8a (Fig. 2D). These results raised the question of whether the aspen CESA stoichiometry generates CSCs and, consequently, CMFs that differ from those found in Norway spruce.

Figure 2.

Secondary cell wall CESA content in developing xylem of Arabidopsis, aspen, and Norway spruce. A, Arabidopsis proteins extracted with the protocol developed here from five biological replicates (Ara1–Ara5) and with the protocol of Hill et al. (2014) from five biological replicates (Ara6–Ara10). B, Norway spruce developing xylem CESA content from five biological replicates (S1–S5). C, Aspen normal wood CESA content from five biological replicates (NW1–NW5). D, Proportion of aspen PtCESA7a/b and CESA8a/b in the total pool shown in C. Error bars represent 1 sd. Four technical replicates were analyzed for each sample. The average is calculated from five biological replicates.

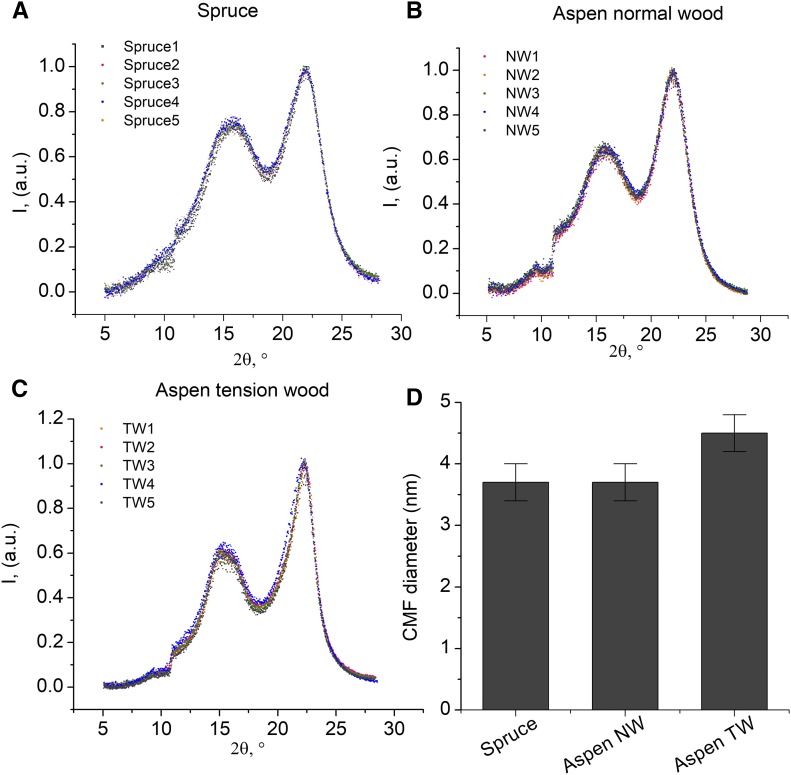

Crystalline CMF Thickness Does Not Differ between Aspen and Norway Spruce

To investigate the relationship between CESA stoichiometry, possible CSC composition, and CMF properties, we first measured the dimensions of CMFs in aspen and Norway spruce wood using WAXS analysis of 100-μm-thick tangential early wood sections. The x-ray diffraction pattern showed no difference in the average crystalline cellulose fibril dimensions between Norway spruce and aspen. The average diameter for both species was 3.7 ± 0.3 nm (Fig. 3, A, B, and D), in agreement with other CFM dimension studies of higher plants showing fairly constant elementary fibril size of 3 to 4 nm (Ding and Himmel, 2006; Fernandes et al., 2011; Newman et al., 2013). This established that the observed CESA stoichiometry difference in the normal wood of aspen and Norway spruce did not affect the crystalline CMF dimensions. This suggested that either (1) aspen is able to tolerate differences in CESA stoichiometry at the CSC assembly level and the active CSCs in aspen also contain an equimolar stoichiometry of CESAs, or (2) there are multiple CESA constellations that can generate a CSC producing CMFs of similar crystalline thickness. It is also possible that the aspen and Norway spruce CMFs differ in their noncrystalline disorganized surface regions, which are not measured by the WAXS analysis.

Figure 3.

A to C, WAXS spectra of cellulose in 100-μm-thick tangential wood sections: Norway spruce early wood (A), aspen normal wood (B), and aspen tension wood (C). D, Average CMF diameter derived from the data in A to C. The average spectra were calculated by normalizing the intensity of the 200 signal of cellulose Iβ at 2 θ of 22.4° to 1. The size of the CMFs was estimated using the Scherrer equation (Scherrer, 1918). n = 5 biological replicate samples. I, Intensity in arbitrary units (a.u.).

CESA8b Expression and Protein Levels Increase in Aspen Tension Wood

As discussed above, the CMFs in the G-layer of P. maximowiczii are thicker than those in the S2 layer of the secondary fiber walls (Mueller and Sugiyama, 2006). Similar to this previous observation, the WAXS analysis of 100-μm-thick tangential tension wood sections revealed wider (4.5 ± 0.3 nm) CMFs in tension wood compared with normal wood (Fig. 3, C and D). Hence, comparison of normal and tension wood provides an experimental system in which to investigate the relationship between CESA stoichiometry and CMF diameter. We hypothesized that, in normal and tension wood, the CESAs are constrained by the same CSC assembly rules, and any differences in the CESA stoichiometry between the two tissues would indicate flexibility in such rules. Furthermore, it would indicate that the CSC composition together with the cell wall matrix effects may play a role in CMF formation.

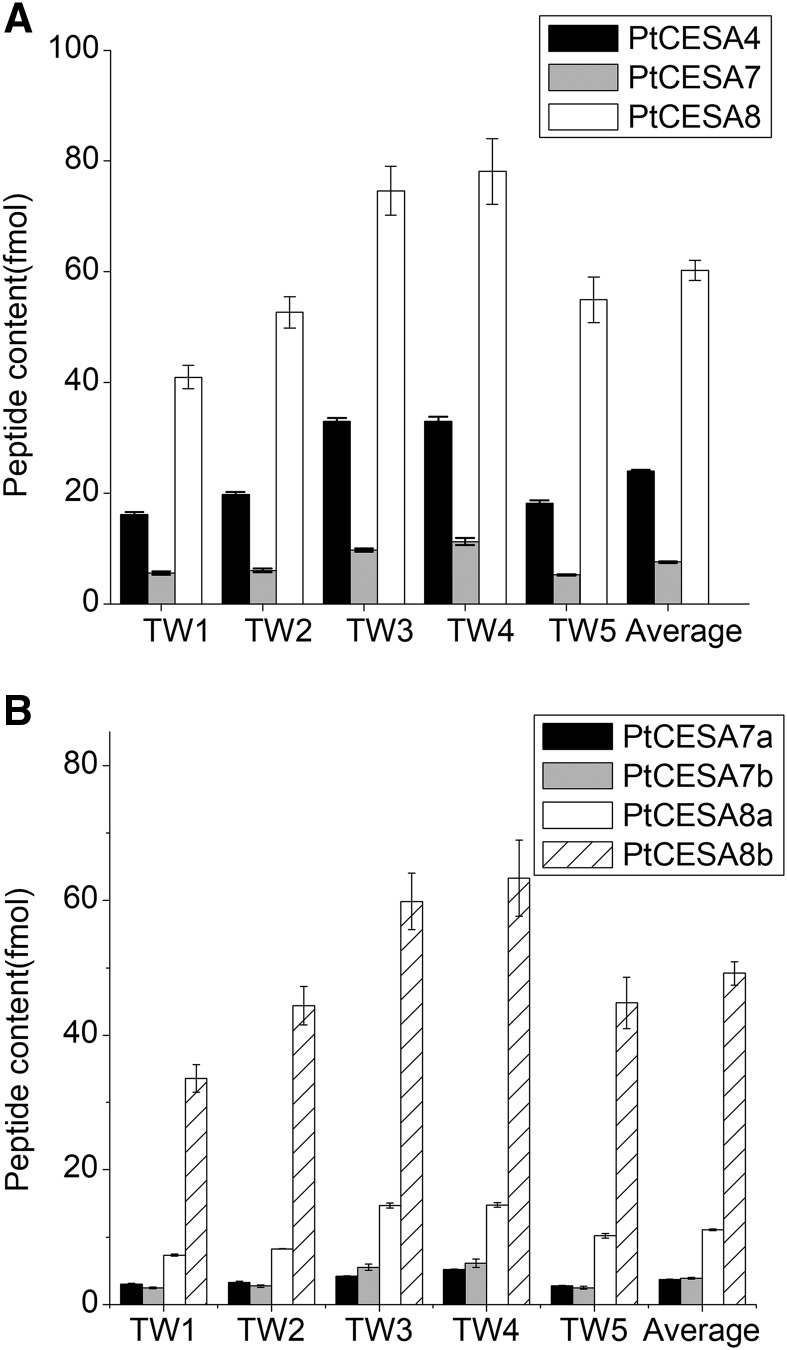

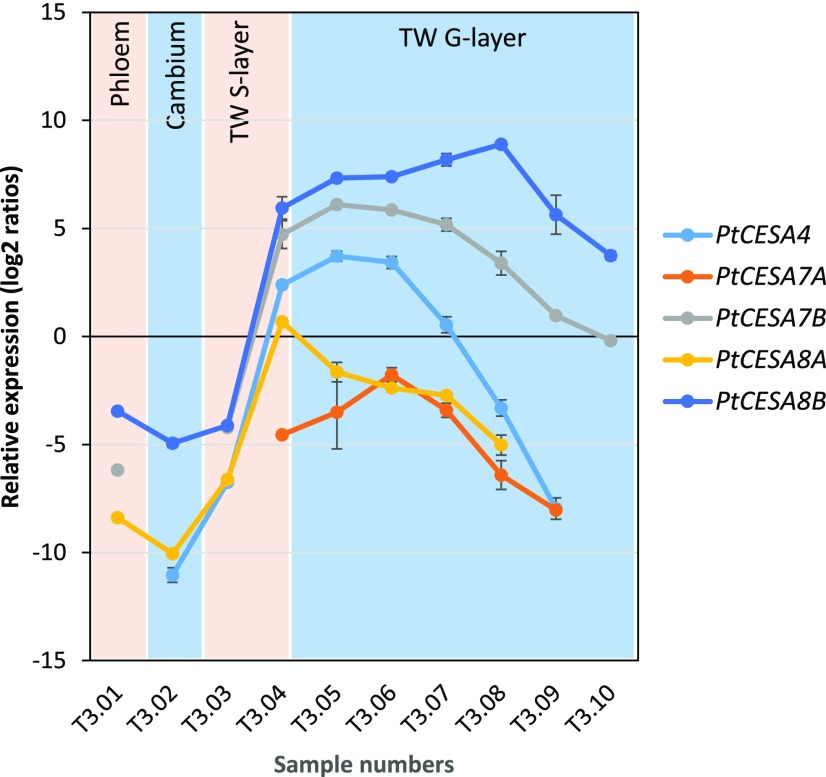

The secondary cell wall CESA ratio in tension wood was approximately 3:1:8 for PtCESA4, PtCESA7a/b, and PtCESA8a/b (Fig. 4A; Supplemental Table S7). Quantification of the PtCESA7a/b and PtCESA8a/b isoforms showed that there was more CESA7b than CESA7a and that CESA8b dominates in tension wood by representing 73% ± 2% of the total secondary cell wall CESA pool (Fig. 4B). To investigate the cause for the shift in CESA stoichiometry between normal and tension wood, we analyzed the corresponding transcript levels in a tangential cryosection series spanning the developing tension wood. In normal wood, the secondary cell wall CESAs have been shown to follow a similar expression pattern across the developing wood (Rajangam et al., 2008; Sundell et al., 2017). The transcript levels of CESA8b continued to increase in tension wood, while the other secondary cell wall CESA transcripts decreased (Fig. 5). Furthermore, this clear transcript pattern shift coincided with G-layer formation. Hence, the CESA transcript and protein stoichiometry results in tension wood point to a specific role for PtCESA8b in G-layer cellulose synthesis. The tension wood results also support a model where the CESA composition in developing xylem fibers has a role in determining CMF properties.

Figure 4.

Secondary cell wall CESA content in aspen tension wood. A, Total PtCESA4, PtCESA7, and PtCESA8 content in tension wood. B, Proportion of aspen PtCESA7a/b and PtCESA8a/b in tension wood. n = 5 biological replicates. Error bars represent 1 sd. Four technical replicates were analyzed for each sample. The average is calculated from five biological replicates.

Figure 5.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of secondary cell wall CESA transcripts during tension wood (TW) formation in aspen. Expression was normalized to two housekeeping genes: ubiquitin and elongation factor 1B α-subunit 2.

DISCUSSION

We developed an MRM proteomics-based CESA quantification method and discovered that the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry in the developing xylem of aspen differs markedly from the stoichiometry in the developing xylem of Arabidopsis and Norway spruce. Our analysis of Arabidopsis confirmed the previously observed 1:1:1 stoichiometry of secondary cell wall CESAs determined using immunoblotting with AtCESA4-, AtCESA7-, and AtCESA8-specific antibodies (Hill et al., 2014). Furthermore, we showed that the secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry is the same 1:1:1 in a gymnosperm tree (Norway spruce). This argues for the generality of a CSC model with one of each of the CESAs per hexamer lobe (hexamer of trimers). The CESA extraction method used in our study and the Hill et al. (2014) Arabidopsis study does not allow the differentiation between CESAs involved in cellulose biosynthesis in active CSCs and CESAs in the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi apparatus-plasma membrane biosynthesis and delivery pathway. Immunoblot analysis of secondary cell wall CESA levels in Arabidopsis cesa4, cesa7, and cesa8 mutants showed that the loss of one CESA isoform decreases the levels of the other two isoforms dramatically, indicating that incomplete CSCs are unstable (Hill et al., 2014). Nevertheless, it is still possible that the stoichiometry of the total CESA pool measured here does not reflect the situation in the functional CSCs. In the case of primary wall CESAs, the ratios were determined using coimmunoprecipitation with CESA isoform-specific antibodies followed by quantification of trypsin-digested CESA-derived peptides by LC-MS (Gonneau et al., 2014). Coimmunoprecipitation allowed the quantification of interacting CESAs, and this way arguably only heteromeric CSCs were analyzed and shown to also exist in 1:1:1 stoichiometry (Gonneau et al., 2014). Our results from Arabidopsis and Norway spruce support the 6 × 3 CESAs as the default CSC composition in these species, but the aspen results showed that deviations from this model are possible.

In aspen normal wood, PtCESA8a/b:PtCESA4:PtCESA7a/b displayed a stoichiometry of 3:2:1. This ratio does not agree with the hexamer of trimers model but rather fits with the original hexamer of hexamers CSC model (Doblin et al., 2002; Ding and Himmel, 2006). However, the latter model has been criticized for being too large in relation to the dimensions of the elementary CMFs synthesized by a CSC and that additional assembly rules as described earlier in the introduction are required to terminate the CSC assembly at 36 CESAs (Newman et al., 2013; Hill et al., 2014). These CSC model constraints make the assumption that all CESAs in a CSC are simultaneously active and that no additional factors are involved in the control of CSC assembly. Evidence of a heterotrimeric composition of Populus spp. CSCs is supported by coimmunoprecipitation of the P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides secondary cell wall CESAs from developing xylem extracts (Song et al., 2010). Moreover, genetic evidence shows that a reduction of the PtdCESA8a and PtdCESA8b transcripts causes a severe growth phenotype, collapsed xylem vessels, and a large reduction in cellulose content (Joshi et al., 2011). These results do not exclude the coexistence of homomeric and heteromeric CSCs in the developing xylem of Populus spp., but they do indicate that heteromeric CSCs containing all three secondary cell wall CESAs are essential for cellulose biosynthesis in the normal wood of Populus spp. With this in mind, it is interesting to consider the possible implications of the observed aspen CESA ratio on CMF biosynthesis.

The diameter of CMFs and the number of glucan chains per CMF relate to the number of catalytically active CESAs per CSC. The analysis of the average thickness of the crystalline CMF part using WAXS showed that the thickness between aspen normal wood and spruce wood is the same, arguing for similarities also in the number of active CESAs in each CSC. The implication is that the stoichiometry in the active CSCs is also 1:1:1 in aspen and that the CSC assembly process in aspen would include a mechanism retaining the excess CESAs in the cytoplasm. Conceivably, CMFs of similar crystalline thickness could be synthesized by different combinations of CESAs. In this case, the developing xylem of aspen may contain CSCs with different secondary cell wall CESA combinations, such as the 3:2:1 hexamer of hexamer CSCs, and/or other combinations, such as homotrimers and heterodimers. It is also worth noting that the calculation of the cellulose crystallinity index from NMR spectra showed that Norway spruce wood cellulose has a slightly higher overall crystallinity than cellulose in aspen wood (Wikberg and Maunu, 2004). Furthermore, NMR analyses have indicated that CMFs contain less ordered glucan chains on the surface of the crystalline CMF core (Wickholm et al., 1998). Hence, it is possible that the degree of surface disorder between Norway spruce and aspen CMFs is different and influenced by the cellulose synthesis process and CSC composition as well as by the other cell wall matrix components interacting with cellulose. The conclusive definition of the active secondary cell wall CSC composition would require the isolation of active CSCs from the plasma membrane of developing xylem cells. Unfortunately, the isolation of CESAs from the plasma membrane of developing xylem cells is technically challenging, as illustrated by our previous proteomics analysis of purified plasma membrane fractions from developing aspen wood, which failed to identify any secondary cell wall CESA proteins (Nilsson et al., 2010). The reason for this is not clear but may be related to the degradation and loss of CESAs during the lengthy plasma membrane purification process.

Despite the uncertainties of how the CESA stoichiometry in total xylem extracts relates to the composition of active CSC, the tension wood results provided further support that deviations from the 1:1:1 model are possible and that the CESA composition in the CSCs may influence CMF properties. Our WAXS measurements showed thicker CMFs in the tension wood G-layer compared with normal wood, and this change coincided with a change in the CESA stoichiometry at both the transcript and protein levels. Increased PtCESA8b expression during G-layer formation, in contrast to decreases in transcripts of other CESAs, suggested that PtCESA8b may form homomeric CSCs during G-layer formation. This interpretation is supported by the protein quantification showing a PtCESA8a/b:PtCESA4:PtCESA7a/b stoichiometry shift from 3:2:1 in normal wood to 8:3:1 in tension wood, with CESA8b accounting for 73% of the total CESA pool. P. tremula × Populus tremuloides CESA8 was recently expressed and purified from Pichia pastoris and shown to synthesize CMFs in vitro (Purushotham et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2017), further supporting the possibility of functional PtCESA8 homomer CSCs also in planta. Interestingly, the diameter of the in vitro PtCESA8-produced CMFs was approximately 4.8 ± 0.1 nm (Purushotham et al., 2016), which is in the same range as the tension wood CMFs (4.5 ± 0.3 nm) we observed in this study. In addition to affecting CMF properties, the CSC composition also may influence the rate of cellulose biosynthesis. This idea is supported by the recent results of Kumar et al. (2018) indicating that, in Arabidopsis, AtCESA8 is the most active of the secondary cell wall CESAs. Differences in the maximal velocity of CESAs may be related to the PtCESA8b dominance in tension wood, where a high rate of cellulose synthesis is required for the G-layer formation.

CONCLUSION

The secondary cell wall CESA stoichiometry results in the developing xylem of the three species confirmed the previous Arabidopsis findings of equimolar stoichiometry and showed that the aspen wood CESA composition differs from that of Arabidopsis and Norway spruce. Furthermore, the CESA stoichiometry changes in aspen tension wood coincide with changing CMF diameter, suggesting a relationship between CESA composition and CMF diameter in tension wood. It is likely that CSCs containing just the single CESA8b isoform are responsible for the G-layer cellulose formation in tension wood. Functional genetics experiments with CESA mutant aspens are needed to test this hypothesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

HPLC solvents including acetonitrile and isopropanol were purchased from Fischer Chemical. Reagents for protein chemistry, including glycerol, potassium chloride, iodoacetamide, 1,4-DTT, ammonium bicarbonate, and SDC, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Formic acid and trifluoroacetic acid were purchased from Fluka. Sequencing-grade trypsin and Lys C/tryspin mixture were purchased from Promega. Trypsin was dissolved using the buffer provided by Promega and stored at −80°C in small aliquots before use. Fresh Milli-Q water was used throughout the experiment.

Plant Sampling

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were grown and harvested as described by Hill et al. (2014). Briefly, stems were harvested from 6- to 7-week-old plants, siliques and leaves were removed, and the stems were immediately ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Aspen (Populus tremula) and spruce (Picea abies) trees were collected in Umea, Sweden, in the first week of July. The trees were between 8 and 13 years old. After harvesting, samples were immediately frozen and kept at −80°C until further use. Differentiating xylem was scraped with a scalpel and ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen with mortar and pestle followed by bead milling (30 s at 30 s−1). The samples were stored at −80°C until extraction and analysis.

Peptide Selection and Sample Preparation

The total protein fraction was extracted from the developing xylem powder with Tris buffer (100 mm potassium chloride, 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 20% glycerol, and Roche Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail) at 4°C and centrifuged at 20,000g for 20 min. The extraction was repeated twice, and the supernatants were combined. The pellets were collected, and then in-solution digestions were carried out using a Lys C/trypsin protease mixture (mass spectrometry grade; Promega V5073) as enzyme to reduce missed cleavage. Briefly, pellets were reduced (5 mm DTT, 1% SDC, and 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate) for 15 min at 90°C and alkylated (iodoacetamide final concentration, 10 mm) at room temperature for 30 min in darkness. Then, the samples were digested with trypsin overnight at 37°C. SDC was precipitated and removed by centrifuging at 20,000g for 10 min. Digested proteins were desalted and concentrated on Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters; 96-well µElution Plate, 5 mg of sorbent), and the eluate was evaporated to dryness in a Mi-Vac Centrifugal Vacuum Concentrator (SP Scientific). Then, 0.1% formic acid was used to reconstitute samples before analysis.

Mass Spectrometry and Data Analysis

Samples were injected onto a nano-flow ultraperformance tandem mass spectrometer system, in which a nanoACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography system (Waters) was connected to a Synapt G2-Si quadrupole-ion mobility-time of flight-high-definition mass spectrometer (Waters). Samples were first loaded onto a trap column (ACQUITY UPLC M-Class Trap, C18, 5 µm, 180 µm i.d. × 20 mm; Waters) at 15 µL min−1 and then eluted and separated on an HSS T3 C18 column (75 µm i.d. × 150 mm, 1.8-µm particles; Waters) using a linear 145-min gradient of 0.5% to 40% solvent B (75% acetonitrile and 25% isopropanol), then balanced with 99% solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) at a flow rate of 300 nL min−1. The separated sample was introduced into the Synapt G2 mass spectrometer through a nanoflow electrospray ionization interface operating in positive mode. All the data were collected in continuum HDMSE mode with drift time-specific collision energy (Distler et al., 2014) and mass corrected using Glu-fibrinopeptide B and Leu enkephalin as reference peptides.

The raw data were subjected to database searching by ProteinLynx Global Server (Waters). For Arabidopsis, the TAIR-10 database was used. For aspen, the P. tremula proteome was downloaded from Uniprot and CESA sequences were added in manually. For spruce, the proteome for P. abies was downloaded from Uniprot and CESA sequences were added in manually. The aspen and spruce CESA sequences were retrieved from the Popgenie and Congenie databases, respectively (Sjödin et al., 2009; Nystedt et al., 2013) using Arabidopsis CESA4, CESA7, and CESA8 as query sequences. Peptide and fragment mass tolerance were set at 10 and 25 ppm, respectively. The number of allowed missed cleavages was set at 1. Fixed modification was set as carbamidomethylation at C. Other variable modifications included acetyl-N-terminal, deamidation at N or Q, oxidation at M, and phosphorylation at S, T, or Y. The false discovery rate was set at 1%. The transmembrane regions were obtained employing the CCtop Web server (Dobson et al., 2015).

Peptide Standard Synthesis and Dissolving

Peptides were synthesized by Cambridge Research Biochemicals with purity greater than 95%. The net peptide content was determined by amino acid analysis and used for concentration calculation. Peptides were fully dissolved in 20% to 80% acetonitrile and stored in small aliquots at −80°C.

Quantification of CESAs

Proteins from five biological replicate aspen and spruce trees and Arabidopsis plants for each sample type (aspen tension wood, normal wood, Arabidopsis stem, and spruce normal wood) were extracted, reduced, digested, and desalted in the same way as described in “Peptide Selection and Sample Preparation” with small differences: (1) Lys C/trypsin mix (Promega) was added and digested for 10 h at 37°C to reduce missed cleavage; and (2) after digestion and prior to desalting, labeled peptide standards were added into each sample. Each sample was injected four times.

For the calibration curves of isotope-labeled peptide standards, digested peptides of spruce, aspen, and Arabidopsis were pooled and used as background to generate a seven-point dilution curve in which the native peptides were held constant and labeled peptides were spiked with increasing concentrations from 0.04 to 30 fmol µL−1. For calibration curves of unlabeled peptide standards, the same sample digest for each species was used as background. Peptide standards were spiked in from 0 to 40 fmol μL−1 to the digest of Arabidopsis, from 0 to 40 fmol μL−1 to the digest of spruce, and from 0 to 180 fmol μL−1 for aspen. All the samples were desalted and evaporated in the same way as described previously. Each injection was repeated four times.

MRM Method

For MRM experiments, all samples were analyzed by reverse-phase liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry using a nanoACQUITY UPLC (Waters) system connected to a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer (Xevo TQ-S; Waters) in direct injection mode. The cycle time took 25 min at a flow rate of 2 µL min−1. Peptides were loaded onto HSS T3 iKey (C18, 1.8 µm, 150 µm i.d. × 50 mm; Waters) in 99% solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) and 1% solvent B (75% acetonitrile and 25% isopropanol). Then, the percentage of solvent B was kept for 0.3 min and ramped to 10% at 0.5 min, and the sample was separated with a 12-min linear gradient from 12% to 41% solvent B, followed by a 3-min linear gradient from 41% to 95% solvent B, and held at 95% for 3 min. The column was then rebalanced by ramping to 1% solvent B in 0.5 min and equilibrated at that concentration for 6 min. A blank injection was run every 10 injections, and no severe carryover effect was observed. A quality-control sample was run every 12 h to monitor the status of the system. Data acquisition was performed using the following parameters: capillary voltage, 3 kV; source temperature, 120°C; and cone gas, 60 L h−1. Five transitions per peptide were monitored in a scheduled way, with a cycle time of 2 s and a 2-min MRM detection window. The cone voltage and collision energy for each transition were optimized using the peptide standard. A summary of transitions, dwell times, and collision energy for each peptide is listed in Supplemental Data Set S1.

MRM Data Analysis and the Calculation of CESA Concentrations

MRM raw data were imported into Skyline (version 3.6; MacCoss lab software, Washington University) with Savitzky-Golay smoothing. Five transitions were monitored for each peptide, and transitions that have strong interference from background were removed during data processing. Three to five transitions per peptide were left after this procedure. All integrated peaks were inspected manually to ensure correct peak detection and accurate integration. The sums of peak areas were used.

The calibration curves for the SIS peptides were constructed as described previously (Mohammed et al., 2015). The peak area ratios of heavy versus light peptides were plotted against the added-in peptide concentration. For the LFS peptides, calibration curves and peak areas were normalized first. The average peak areas of the six SIS peptides in each injection were normalized to the same level. Normalized peak areas were plotted against the amount of peptide spiked in, and linear regression analyses were performed for each peptide. Because there are native peptides in the sample background, the true linear regression would have a lower y intercept than the generated linear curve but the same slope. The true y intercept, which is the peak area of background noise for each peptide, was integrated and used to generate the true calibration curve.

Transcript Analysis

RT-qPCR analysis of poplar secondary cell wall CESAs was performed as described previously (Rajangam et al., 2008). Briefly, P. tremula trees from a natural population of approximately 5-m-high trees growing outside Umea were leaned for 2 weeks to induce tension wood formation. Stem pieces were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −70°C until further use. Then, 30-µm tangential sections were obtained from tension wood sides of the stem pieces. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and RT-qPCR analysis were performed as described (Rajangam et al., 2008). A list of all primers used in the RT-qPCR analysis is shown in Supplemental Table S8.

WAXS

WAXS was measured using an Anton Paar SAXSpoint 2.0 instrument. The wood samples were mounted with the fibers orientated horizontally. Measurements were performed with a Cu Kα1 radiation (γ = 1.541 Å). Ten frames each with an acquisition time of 200 s were averaged for each sample. A background measurement in vacuum was acquired using the same settings and subtracted from the sample measurements.

Average spectra from five different samples were calculated by normalizing the intensity of the 200 signal of cellulose Iβ at 2 θ of 22.4° to 1. The size of the CMFs was estimated using the Scherrer equation relating the crystallite size, d, to the width of the signal at half its maximum, β, in radians (Scherrer, 1918):

where K is a constant set to 0.9, γ is the radiation wavelength, and θ is the position of the signal, in the case of the CMFs, the 200 signal of cellulose Iβ at 2 θ of 22.4°.

Accession Numbers

All accession numbers are listed in Table I.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. CESA digestion and peptide release time-course analysis.

Supplemental Figure S2. Aspen CESA peptide peak area normalization.

Supplemental Figure S3. Norway spruce CESA peptide peak area normalization.

Supplemental Figure S4. Arabidopsis CESA peptide peak area normalization.

Supplemental Figure S5. Standard curves for all studied peptides.

Supplemental Table S1. List of all detected CESA peptides from aspen, Arabidopsis, and Norway spruce.

Supplemental Table S2. QA test results for the recovery of the 27 peptides.

Supplemental Table S3. Arabidopsis CESA peptide quantification results.

Supplemental Table S4. Arabidopsis CESA peptide quantification results using the extraction method reported by Hill et al. (2014).

Supplemental Table S5. Norway spruce wood peptide quantification results.

Supplemental Table S6. Aspen normal wood peptide quantification results.

Supplemental Table S7. Aspen tension wood peptide quantification results.

Supplemental Table S8. List of primers used in RT-qPCR analysis.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Summary of transitions, dwell times, retention times, and collision energy for each peptide.

Dive Curated Terms

The following phenotypic, genotypic, and functional terms are of significance to the work described in this paper:

Acknowledgments

We thank Lennart Salmen at RISE, the Swedish Research Institute, for help with the WAXS analyses.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Kempe Foundation fellowship to X.Z., Bio4Energy (Swedish Programme for Renewable Energy), the Umeå Plant Science Centre, Berzelii Centre for Forest Biotechnology funded by VINNOVA, and the Swedish Research Council Formas (NANOWOOD).

References

- Arioli T, Peng L, Betzner AS, Burn J, Wittke W, Herth W, Camilleri C, Höfte H, Plazinski J, Birch R, et al. (1998) Molecular analysis of cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Science 279: 717–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brönstrup M. (2004) Absolute quantification strategies in proteomics based on mass spectrometry. Expert Rev Proteomics 1: 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Leijon F, Bulone V (2012) Radiometric and spectrophotometric in vitro assays of glycosyltransferases involved in plant cell wall carbohydrate biosynthesis. Nat Protoc 7: 1634–1650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiva C, Ortega M, Sabidó E (2014) Influence of the digestion technique, protease, and missed cleavage peptides in protein quantitation. J Proteome Res 13: 3979–3986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Purushotham P, Fang C, Maranas C, Díaz-Moreno SM, Bulone V, Zimmer J, Kumar M, Nixon BT (2017) Synthesis and self-assembly of cellulose microfibrils from reconstituted cellulose synthase. Plant Physiol 175: 146–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desprez T, Juraniec M, Crowell EF, Jouy H, Pochylova Z, Parcy F, Höfte H, Gonneau M, Vernhettes S (2007) Organization of cellulose synthase complexes involved in primary cell wall synthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15572–15577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding SY, Himmel ME (2006) The maize primary cell wall microfibril: a new model derived from direct visualization. J Agric Food Chem 54: 597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distler U, Kuharev J, Navarro P, Levin Y, Schild H, Tenzer S (2014) Drift time-specific collision energies enable deep-coverage data-independent acquisition proteomics. Nat Methods 11: 167–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doblin MS, Kurek I, Jacob-Wilk D, Delmer DP (2002) Cellulose biosynthesis in plants: from genes to rosettes. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 1407–1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson L, Reményi I, Tusnády GE (2015) CCTOP: a Consensus Constrained TOPology prediction web server. Nucleic Acids Res 43: W408–W412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erde J, Loo RRO, Loo JA (2014) Enhanced FASP (eFASP) to increase proteome coverage and sample recovery for quantitative proteomic experiments. J Proteome Res 13: 1885–1895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felten J, Sundberg B (2013) Biology, chemistry and structure of tension wood. In Fromm J, ed, Cellular Aspects of Wood Formation. Springer, Berlin, pp 203–224 [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AN, Thomas LH, Altaner CM, Callow P, Forsyth VT, Apperley DC, Kennedy CJ, Jarvis MC (2011) Nanostructure of cellulose microfibrils in spruce wood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: E1195–E1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino T. (1998) Changes in the three dimensional architecture of the cell wall during lignification of xylem cells in Eucalyptus tereticornis. Holzforschung 52: 111–116 [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LJ. (2012) The hierarchical structure and mechanics of plant materials. J R Soc Interface 9: 2749–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatter T, Ludwig C, Ahrné E, Aebersold R, Heck AJR, Schmidt A (2012) Large-scale quantitative assessment of different in-solution protein digestion protocols reveals superior cleavage efficiency of tandem Lys-C/trypsin proteolysis over trypsin digestion. J Proteome Res 11: 5145–5156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonneau M, Desprez T, Guillot A, Vernhettes S, Höfte H (2014) Catalytic subunit stoichiometry within the cellulose synthase complex. Plant Physiol 166: 1709–1712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herth W. (1983) Arrays of plasma-membrane “rosettes” involved in cellulose microfibril formation of Spirogyra. Planta 159: 347–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JL Jr, Hammudi MB, Tien M (2014) The Arabidopsis cellulose synthase complex: a proposed hexamer of CESA trimers in an equimolar stoichiometry. Plant Cell 26: 4834–4842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MC. (2018) Structure of native cellulose microfibrils, the starting point for nanocellulose manufacture. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 376: 20170045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokipii-Lukkari S, Sundell D, Nilsson O, Hvidsten TR, Street NR, Tuominen H (2017) NorWood: a gene expression resource for evo-devo studies of conifer wood development. New Phytol 216: 482–494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi CP, Thammannagowda S, Fujino T, Gou JQ, Avci U, Haigler CH, McDonnell LM, Mansfield SD, Mengesha B, Carpita NC, et al. (2011) Perturbation of wood cellulose synthesis causes pleiotropic effects in transgenic aspen. Mol Plant 4: 331–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Laosinchai W, Itoh T, Cui X, Linder CR, Brown RM Jr (1999) Immunogold labeling of rosette terminal cellulose-synthesizing complexes in the vascular plant Vigna angularis. Plant Cell 11: 2075–2086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Turner S (2015) Protocol: a medium-throughput method for determination of cellulose content from single stem pieces of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Methods 11: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Thammannagowda S, Bulone V, Chiang V, Han KH, Joshi CP, Mansfield SD, Mellerowicz E, Sundberg B, Teeri T, et al. (2009) An update on the nomenclature for the cellulose synthase genes in Populus. Trends Plant Sci 14: 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M, Mishra L, Carr P, Pilling M, Gardner P, Mansfield SD, Turner S (2018) Exploiting CELLULOSE SYNTHASE (CESA) class specificity to probe cellulose microfibril biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 177: 151–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange V, Picotti P, Domon B, Aebersold R (2008) Selected reaction monitoring for quantitative proteomics: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol 4: 222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Wang K, Liu Z, Lin H, Yu L (2015) Enhanced SDC-assisted digestion coupled with lipid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for shotgun analysis of membrane proteome. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1002: 144–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane HE, Döring A, Persson S (2014) The cell biology of cellulose synthesis. Annu Rev Plant Biol 65: 69–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed Y, Percy AJ, Chambers AG, Borchers CH (2015) Qualis-SIS: automated standard curve generation and quality assessment for multiplexed targeted quantitative proteomic experiments with labeled standards. J Proteome Res 14: 1137–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MBM, Sugiyama J (2006) Direct investigation of the structural properties of tension wood cellulose microfibrils using microbeam x-ray fibre diffraction. Holzforschung 60: 474–479 [Google Scholar]

- Mueller SC, Brown RM Jr (1980) Evidence for an intramembrane component associated with a cellulose microfibril-synthesizing complex in higher plants. J Cell Biol 84: 315–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman RH, Hill SJ, Harris PJ (2013) Wide-angle x-ray scattering and solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance data combined to test models for cellulose microfibrils in mung bean cell walls. Plant Physiol 163: 1558–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson R, Bernfur K, Gustavsson N, Bygdell J, Wingsle G, Larsson C (2010) Proteomics of plasma membranes from poplar trees reveals tissue distribution of transporters, receptors, and proteins in cell wall formation. Mol Cell Proteomics 9: 368–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt B, Street NR, Wetterbom A, Zuccolo A, Lin YC, Scofield DG, Vezzi F, Delhomme N, Giacomello S, Alexeyenko A, et al. (2013) The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497: 579–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Paredez A, Carroll A, Palsdottir H, Doblin M, Poindexter P, Khitrov N, Auer M, Somerville CR (2007) Genetic evidence for three unique components in primary cell-wall cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 15566–15571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushotham P, Cho SH, Díaz-Moreno SM, Kumar M, Nixon BT, Bulone V, Zimmer J (2016) A single heterologously expressed plant cellulose synthase isoform is sufficient for cellulose microfibril formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 11360–11365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajangam AS, Kumar M, Aspeborg H, Guerriero G, Arvestad L, Pansri P, Brown CJ, Hober S, Blomqvist K, Divne C, et al. (2008) MAP20, a microtubule-associated protein in the secondary cell walls of hybrid aspen, is a target of the cellulose synthesis inhibitor 2,6-dichlorobenzonitrile. Plant Physiol 148: 1283–1294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saveliev S, Bratz M, Zubarev R, Szapacs M, Budamgunta H, Urh M (2013) Trypsin/Lys-C protease mix for enhanced protein mass spectrometry analysis. Nat Methods 10: [Google Scholar]

- Scheible WR, Eshed R, Richmond T, Delmer D, Somerville C (2001) Modifications of cellulose synthase confer resistance to isoxaben and thiazolidinone herbicides in Arabidopsis Ixr1 mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 10079–10084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer P. (1918) Bestimmungen der Grösse und der inneren Struktur von Kolloidteilchen mittels Röntgenstrahlen. Nachr Ges Wiss Gottingen 1918: 98–100 [Google Scholar]

- Shuford CM, Sederoff RR, Chiang VL, Muddiman DC (2012) Peptide production and decay rates affect the quantitative accuracy of protein cleavage isotope dilution mass spectrometry (PC-IDMS). Mol Cell Proteomics 11: 814–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjödin A, Street NR, Sandberg G, Gustafsson P, Jansson S (2009) The Populus Genome Integrative Explorer (PopGenIE): a new resource for exploring the Populus genome. New Phytol 182: 1013–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šlechtová T, Gilar M, Kalíková K, Tesařová E (2015) Insight into trypsin miscleavage: comparison of kinetic constants of problematic peptide sequences. Anal Chem 87: 7636–7643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville C. (2006) Cellulose synthesis in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 53–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Shen J, Li L (2010) Characterization of cellulose synthase complexes in Populus xylem differentiation. New Phytol 187: 777–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell D, Street NR, Kumar M, Mellerowicz EJ, Kucukoglu M, Johnsson C, Kumar V, Mannapperuma C, Delhomme N, Nilsson O, et al. (2017) AspWood: high-spatial-resolution transcriptome profiles reveal uncharacterized modularity of wood formation in Populus tremula. Plant Cell 29: 1585–1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata N, Taniguchi T (2015) Expression divergence of cellulose synthase (CesA) genes after a recent whole genome duplication event in Populus. Planta 241: 29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor NG, Howells RM, Huttly AK, Vickers K, Turner SR (2003) Interactions among three distinct CesA proteins essential for cellulose synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 1450–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LH, Forsyth VT, Sturcová A, Kennedy CJ, May RP, Altaner CM, Apperley DC, Wess TJ, Jarvis MC (2013) Structure of cellulose microfibrils in primary cell walls from collenchyma. Plant Physiol 161: 465–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SR, Somerville CR (1997) Collapsed xylem phenotype of Arabidopsis identifies mutants deficient in cellulose deposition in the secondary cell wall. Plant Cell 9: 689–701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuskan GA, Difazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, et al. (2006) The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313: 1596–1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickholm K, Larson PT, Iversen T (1998) Assignment of non-crystalline forms in cellulose I by CP/MAS C-13 NMR spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res 312: 123–129 [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg H, Maunu SL (2004) Characterisation of thermally modified hard-and softwood by 13C CPMAS NMR. Carbohydr Polym 58: 461–466 [Google Scholar]