Abstract

Background & Aims

Single-center studies have reported excellent outcomes of patients who underwent liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after successful down-staging (reduction of tumor burden with local-regional therapy), but multi-center studies are lacking. We performed a multi-center study, applying a uniform down-staging protocol, to assess outcomes of liver transplantation and performed an intention to treat analysis. We analyzed factors associated with treatment failure, defined as dropout from the liver transplant waitlist due to tumor progression, liver-related death without transplant, or recurrence of HCC after transplant.

Methods

We performed a retrospective multi-center study of 187 consecutive adults with HCC enrolled in the down-staging protocol at 3 liver transplant centers in California (Region 5), from 2002 through 2012. All patients underwent abdominal imaging 1 month after each local-regional treatment, and at a minimum of once every 3 months. The primary outcome was probability of treatment failure.

Results

Liver transplantation was performed after successful down staging in 109 patients (58%). Tumor explant from only 1 patient had poorly differentiated grade and 7 (6.4%) had vascular invasion. Based on Kaplan-Meier analysis of data collected a median 4.3 years after liver transplantation, 95% of patients would survive 1 year and 80% of patients would survive 5 years; probabilities of recurrence-free survival were 95% and 87%, respectively. There were no center-specific differences in survival in the intention to treat analysis (P=.62), in survival after liver transplantation (P=.95), or in recurrence of HCC (P=.99). Patients were removed from the liver transplantation waitlist due to tumor progression in (n=59, 32%) or liver-related death without liver transplantation (n=9, 5%). Factors associated with treatment failure, based on multivariable analysis, were pretreatment levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) >1000 ng/mL (hazard ratio, 3.3; P<.001) and Child Pugh class B or C (hazard ratio, 1.6; P<.001). The probability of treatment failure at 2 years from the first down-staging procedure was 100% for patients with levels of AFP >1000 and Child Pugh class B or C vs 29.4% for patients with neither risk factor (P<.001).

Conclusion

In a retrospective, multi-center study on HCC down staging under a uniform protocol, we found patients to have excellent outcomes following liver transplantation, with no center-specific effects. Our findings support application of the down-staging protocol on a broader scale. Patients with Child Pugh class B or C and AFP >1000 are unlikely to benefit from down staging.

Keywords: local regional therapy (LRT), LT, tumor recurrence, waitlist dropout

INTRODUCTION

Fueled by the hepatitis C and fatty liver disease epidemics, the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is projected to increase for at least another decade in the United States1. With HCC becoming a leading indication for liver transplant (LT)2,3, there have been ongoing efforts of the transplant community to refine LT selection criteria to ensure good outcome while attempting to meet the growing demands. The Milan criteria (1 lesion ≤5 cm, 2-3 lesions ≤3 cm)4 have been the benchmark for the selection of candidates with HCC for LT for 2 decades5. There have been a number of proposals to expand tumor size limits modestly beyond Milan criteria6, including the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) criteria7 and the “up-to-seven” criteria8, both associated with an estimated 5-year post-transplant survival only slightly below that with the Milan criteria. One of the limitations of expansion of the limits in tumor size/number alone is that it does not account for the effects of local regional therapy (LRT), which has been widely used to control tumor growth as a bridge to LT, particularly if the waiting time is prolonged5.

Tumor down-staging, defined as a reduction in tumor burden using LRT to meet acceptable criteria for LT9, has been identified as one of the priorities for research in two national conferences on HCC10,11. Down-staging is an attractive alternative to simply expanding the tumor size limits since response to down-staging treatment may also serve as a prognostic marker and a tool to select a subgroup of patients with more favorable tumor biology who will likely do well after LT9. Although published results on tumor down-staging before LT are encouraging, they are based entirely on single center experience12-15. In this first multicenter study, we aimed to assess post-LT and intention to treat outcomes under a uniform down-staging protocol. We also aimed to assess factors associated with treatment failure, which may help refine inclusion criteria for down-staging and improve overall outcome.

METHODS

Down-staging Protocol

The UNOS Region 5 down-staging protocol adopted from UCSF has previously been described in detail12 (Table 1). The present study included consecutive adult HCC patients enrolled in the down-staging protocol at three LT centers in Region 5 (UCSF, California Pacific Medical Center, and Scripps Green Hospital) from 2002-2012. A minimum follow-up of 6 months after the first down-staging treatment was required for inclusion. The diagnosis of HCC for a lesion ≥ 1cm was based on either quadruple-phase computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium contrast showing arterial phase enhancement and washout during the delayed images, or if a lesion showed interval growth. Hepatic nodules <1 cm were not counted as HCC.

Table 1.

Region 5 Down-staging Protocol

Inclusion Criteria

|

Criteria for successful down-staging

|

Criteria for down-staging failure and exclusion from liver transplant

|

Additional Guidelines

|

The specific type of LRT used was at the discretion of each of the three center’s multidisciplinary tumor board based on a review of imaging studies and not pre-specified in the down-staging protocol. All patients included in the down-staging protocol underwent CT or MRI of the abdomen at 1 month after each LRT, and at a minimum of once every 3 months. Imaging criteria for successful down-staging included a decrease size of the tumor(s) to within Milan criteria, or complete tumor necrosis with no contrast enhancement. Response to treatment was based on radiographic measurements of the maximal diameter of viable tumors, not including the area of necrosis resulting from LRT9. Each center applied LRT with repetitive interventions if needed to achieve complete necrosis of all tumor nodules if possible. A minimum observation period of 3 months after down-staging was required to be certain that the tumor stage remained within Milan criteria before LT.

Following successful down-staging of HCC, patients at each center were eligible for priority listing under the Model of End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) exception system. This down-staging protocol has been incorporated into UNOS Region 5 policy, whereby patients are eligible for MELD exception after successful down-staging without the need for individual petition for approval.

Histopathologic Analysis

In patients who underwent LT after successful down-staging, explant histopathologic features evaluated included tumor size, number of tumor nodules, histologic grade of differentiation based on the Edmondson and Steiner criteria16, and the presence of micro- or macro-vascular invasion. Pathologic tumor staging of viable tumors was based on the UNOS TNM staging system9.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was probability of treatment failure. Treatment failure was defined as dropout from the down-staging protocol due to tumor progression, liver-related death without LT, or post-LT HCC recurrence. The principle of down-staging is to select a subgroup of patients who are likely to demonstrate response to tumor down-staging and also do well after liver transplant with a low risk of tumor recurrence. Defining treatment failure in this way allows for the identification of patients who would benefit the most from down-staging. Secondary outcomes included probability of successful down-staging, intention-to-treat survival, and post-LT HCC recurrence and survival. Follow-up time was censored at the first of post-LT death, last follow-up, or 5 years after LT. For patients developing a non-liver disease medical contraindication to LT, were no longer interested in undergoing LT, or were noncompliant with each center’s transplant policies, follow-up was censored at the time of delisting or removal from the protocol.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-squared and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to assess differences between subgroups. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to estimate survival functions, cumulative probabilities, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Subgroup and center comparisons were evaluated using the log-rank test. To determine characteristics associated with treatment failure, univariate logistic regression evaluated the likelihood of never achieving down-staging and estimated odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs. The association of explanatory variables was explored using univariate and multivariable hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CIs estimated by competing risks for post-LT HCC recurrence and Cox proportional hazards regression for treatment failure. To categorize continuous variables, multiple cutoffs were tested and evaluated using Akaike information criteria (AIC) with lower AIC values indicating better model fit. Explanatory variables with a univariate p-value <0.1 were included in the multivariable analysis with the final model selected by backward elimination (p for removal >0.05).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics and LRT

The baseline characteristics and details of LRT are presented in Table 2. The majority of the cohort (69.5%) was from Center 1. At the time of first down-staging procedure, median MELD was 10, 57.5% were Child’s class A (CTP 5-6), 31.8% were Child’s B (CTP 7-9), and 10.6% were Child’s C (CTP 10-15). There were 38.0% with a single lesion, 51.3% with 2-3 lesions, and 10.7% with 4-5 lesions. Median baseline alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was 24 (IQR 8-154) and 10.2% had an AFP ≥1000 ng/ml. There was a similar distribution of LRT received with 25.7% undergoing a single procedure and 26.2% requiring ≥4 LRTs. Trans-arterial chemoembolization (TACE) was the mainstay of LRT with 50.3% receiving TACE alone and 43.3% receiving a combination of TACE and radiofrequency ablation (RFA). There were no significant differences among the 3 centers in baseline characteristics or type and number of LRT received.

Table 2.

Baseline and Tumor Treatment Characteristics of the Down-staging Group

| Variable | Overall (n=187) |

Center 1 (n=130) |

Center 2 (n=33) |

Center 3 (n=24) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Median Age (IQR) | 58 (54–63) | 58 (54–63) | 59 (54–65) | 59 (54–65) | 0.67 |

|

| |||||

| Male Gender (%) | 153 (81.8) | 106 (81.5) | 27 (81.8) | 20 (83.3) | 0.75 |

|

| |||||

| Race/Ethnicity (%) | 0.83 | ||||

| Caucasian | 81 (43.3) | 54 (41.5) | 16 (48.5) | 11 (45.8) | |

| Asian | 67 (35.8) | 51 (39.2) | 10 (30.3) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Hispanic | 21 (11.2) | 13 (10.0) | 4 (12.1) | 4 (16.7) | |

| African American | 12 (6.4) | 8 (6.2) | 2 (6.1) | 2 (8.3) | |

|

| |||||

| Liver Disease Etiology (%) | 0.51 | ||||

| Hepatitis C†† | 106 (56.7) | 73 (56.2) | 18 (54.5) | 15 (62.5) | |

| Hepatitis B | 46 (24.6) | 37 (28.5) | 6 (18.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Alcohol | 17 (9.1) | 11 (8.5) | 4 (12.1) | 2 (8.3) | |

| NAFLD | 15 (8.0) | 8 (6.2) | 4 (12.1) | 3 (12.5) | |

|

| |||||

| Median CTP Score (IQR)* | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 7 (6–7) | 0.73 |

| Child’s A (CTP 5–6, %) | 103 (57.5) | 72 (56.3) | 20 (64.5) | 11 (55.0) | 0.87 |

| Child’s B (CTP 7–9, %) | 57 (31.8) | 43 (33.1) | 8 (25.8) | 6 (30.0) | |

| Child’s C (CTP 10–15, %) | 19 (10.6) | 13 (10.0) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (15.0) | |

|

| |||||

| Median MELD (IQR)** | 10 (7–12) | 10 (7–12) | 11 (7–13) | 10 (8–12) | 0.26 |

|

| |||||

| Median AFP ng/mL (IQR) | 24 (8–154) | 21 (7–176) | 32 (18–77) | 14 (6–88) | 0.68 |

| <100 (%) | 132 (70.6) | 90 (69.2) | 24 (72.7) | 18 (75.0) | 0.82 |

| 100–999 (%) | 36 (19.2) | 26 (20.0) | 7 (21.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| >1000 (%) | 19 (10.2) | 14 (10.8) | 2 (6.1) | 3 (12.5) | |

|

| |||||

| Largest Tumor Size (IQR) | 0.32 | ||||

| 1 lesion n=71 (38.0%) | 6.0 cm (5.7–6.7) | 6.3 (5.9–6.7) | 5.8 (5.2–6.8) | 5.7 (5.5–6.2) | |

| 2–3 lesions n=96 (51.3%) | 4.0 cm (3.5–4.7) | 4.2 (3.5–4.8) | 4.1 (3.5–4.6) | 3.3 (3.1–3.9) | |

| 4–5 lesions n=20 (10.7%) | 2.3 cm (2.0–2.7) | 2.3 (2.0–2.7) | 2.7 (2.2–3.0) | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | |

|

| |||||

| Type of LRT Received (%) | 0.05 | ||||

| TACE only | 94 (50.3) | 58 (44.6) | 18 (54.5) | 18 (75.0) | |

| RFA only | 12 (6.4) | 9 (6.9) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (8.3) | |

| TACE + RFA | 81 (43.3) | 63 (48.5) | 14 (42.4) | 4 (16.7) | |

|

| |||||

| Number LRT Received (%) | 0.63 | ||||

| 1 | 48 (25.7) | 35 (26.9) | 5 (15.2) | 8 (33.3) | |

| 2 | 52 (27.8) | 36 (27.7) | 9 (27.3) | 7 (29.2) | |

| 3 | 38 (20.3) | 24 (18.5) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (16.7) | |

| >4 | 49 (26.2) | 35 (26.9) | 9 (27.3) | 5 (20.8) | |

n=179;

n=178

Of the 106 patients with hepatitis C infection, none had received direct-acting antiviral agents before liver transplant; 62% were genotype 1 and 23% were genotype 3. Overall, 41% had positive hepatitis C RNA at the time of liver transplant.

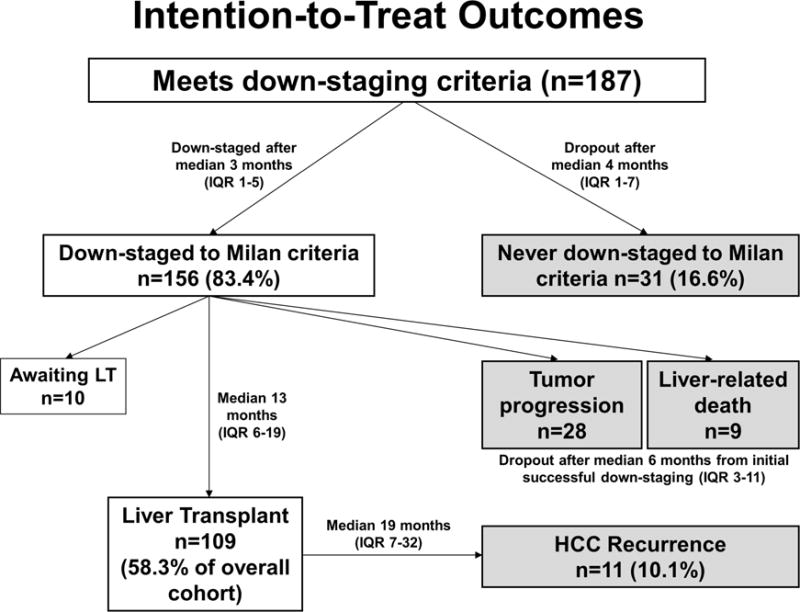

Intention-to-treat Outcome

The intention-to-treat outcome is summarized in Figure 1 and stratified by study center in Table 3. Overall, 31 patients (16.6%) were never down-staged to within Milan criteria and dropped out after a median of 4.2 months from first LRT (IQR 1.3-7.2). Among them, 13 (41.9%) received only 1 LRT before tumor progression. In logistic regression analysis, the only factor predicting inability to ever achieve tumor down-staging was pre-treatment AFP ≥100 (OR 2.7, p=0.02) and AFP ≥1000 (OR 3.8, p=0.01). The probability of not being able to be down-staged was 33.0% in those with an AFP ≥1000 compared to 15.2% for AFP 100-999 and 9.3% for AFP <100 (p=0.03). Number and size of tumors, MELD score, Child’s class, and number of LRT were not significant predictors of inability to be down-staged.

Figure 1.

Summary of the intention-to-treat outcome of the 187 patients enrolled in the down-staging protocol.

Table 3.

Down-staging Outcomes Stratified by Center

| Overall (n=187) | Center 1 (n=130) | Center 2 (n=33) | Center 3 (n=24) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Initial Down-staging Response (%) | 0.19 | ||||

| Down-staged | 156 (83.4) | 110 (84.6) | 29 (87.9) | 17 (70.8) | |

| Never Down-staged | 31 (16.6) | 20 (15.4) | 4 (12.1) | 7 (29.2) | |

|

| |||||

| Dropout After Initial Down-Staging (%) | 37 (19.8) | 26 (20.0) | 7 (21.2) | 4 (16.7) | 0.95 |

| Dropout due to Tumor Progression | 28 (15.0) | 20 (15.4) | 5 (15.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Dropout due to Liver-related Death | 9 (4.8) | 6 (4.6) | 2 (6.1) | 1 (4.2) | |

|

| |||||

| Liver Transplant (%) | 109 (58.3) | 75 (57.7) | 21 (63.6) | 13 (54.2) | 0.75 |

|

| |||||

| Post-transplant Recurrence (%) | 11 (10.1) | 8 (10.7) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (7.7) | 0.94 |

Successful down-staging to within Milan criteria was achieved in 156 patients (83.4%) after a median of 2.7 months (IQR 1.4-4.9). Among them, 67.9% were down-staged after a single LRT while 32.1% required multiple treatments. The cumulative probability of successful down-staging from first LRT was 35.5% at 2 months, 74.5% at 6 months, and 86.4 at 12 months.

Of the 156 patients initially down-staged, 28 (17.9%) experienced waitlist dropout due to subsequent tumor progression and 9 (5.8%) had liver-related death without LT. The median time from listing with MELD exception to dropout in these 37 patients was 6.2 months (IQR 3.2-10.8). Successful down-staging to Milan criteria was maintained for >3 months in 75.7% and >6 months in 56.7%, before tumor progression and removal from the waiting list.

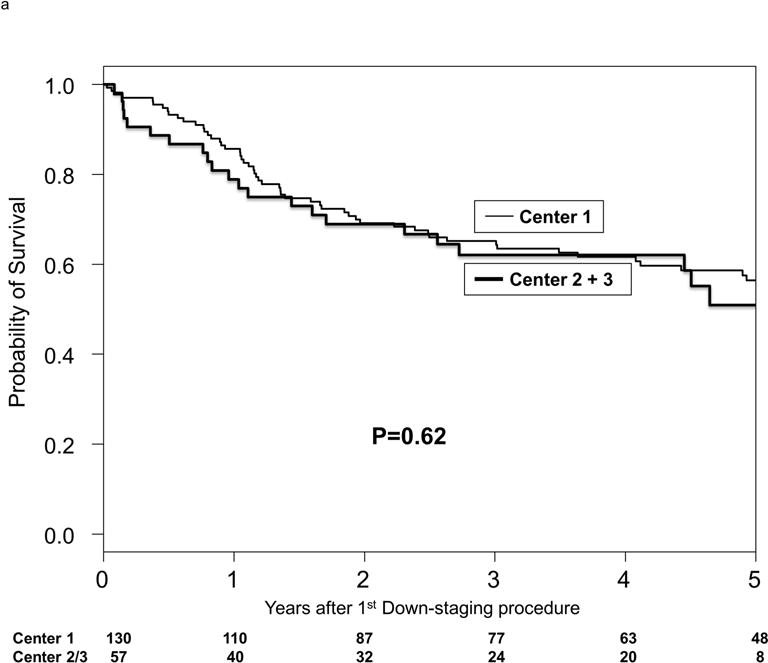

At last follow-up, 109 patients (58.3% of the entire cohort) had received LT and 10 patients were still active on the waiting list. The median time from MELD-exception listing after successful down-staging to LT was 12.6 months (IQR 5.8-18.6). Of the 109 LT recipients, 3 (2.8%) received live donor LT (all at center 1) at 3 to 4.8 months after achieving successful down-staging. The Kaplan-Meier intention-to-treat survival at 1 and 5 years from first down-staging procedure was 84.3% and 55.4%. Intention-to-treat survival at 1 year from first down-staging procedure was 37.6% in those never able to be down-staged, 72.9% in those who dropped out after initial successful down-staging, and 100% in those who underwent LT (p<0.001). There were no center-specific differences in intention-to-treat survival (Figure 2a).

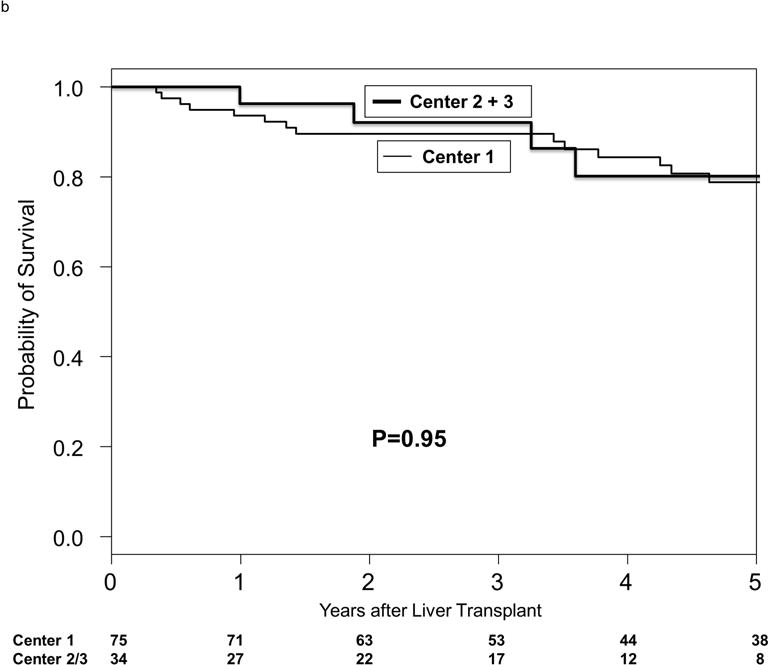

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier probabilities of (a) intention-to-treat survival by center and (b) post-transplant survival by center.

Explant Histopathologic Characteristics

Complete tumor necrosis from LRT (no residual tumors in explant) was observed in 34.9%. Tumor stage was within Milan criteria (T1/T2) in 45.9%, and beyond Milan criteria (T3/T4) in 19.3% due to under-staging by imaging. The latter group included one patient with macro-vascular invasion (T4b) and one with lymph node invasion (N1). Only 6.4% had micro-vascular invasion. Among 71 patients with viable tumors, almost all had either well-differentiated (35.2%) or moderately-differentiated tumors (63.4%), and only a single patient (1.4%) had poorly-differentiated tumor grade. There were no center-specific differences in explant histologic characteristics.

Post-transplant Survival and HCC Recurrence

Median post-LT follow-up was 4.3 years (IQR 2.4-6.6). The Kaplan-Meier post-LT survival at 1 and 5 years was 94.5% and 79.7%. There were no center-specific differences in post-LT survival (Figure 2b). HCC recurrence developed in 11 patients (10.1%) at a median of 19.1 months (IQR 7.3-31.7) from LT. The Kaplan-Meier recurrence-free probability at 1 and 5 years after LT was 95.4% and 87.3%. The recurrence-free probability at 5 years after LT were not significantly different between centers (87% in center 1 and 88.9% in centers 2 and 3 combined; p=0.99). Predictors of post-LT HCC recurrence on competing risks multivariable analysis included AFP >500 ng/ml (HR 8.41, 95% CI 2.02-35.64, p=0.003) and vascular invasion on explant (HR 7.37, 95% CI 1.48-37.34, p=0.02). Wait time from first down-staging treatment to LT, number or type of LRT, center, and explant grade and stage were not significant predictors of HCC recurrence.

Treatment Failure

A total of 79 patients (42.2%) were classified as treatment failures (Figure 1). Kaplan-Meier probability of treatment failure at 1 and 5 years from first down-staging treatment was 25.3% and 44.3%. There were no center-specific differences in probability of treatment failure (p=0.53). In univariate analysis, significant predictors of treatment failure included pre-treatment AFP ≥20 ng/ml, with increasing hazard ratios for increasing baseline AFP values. There was a non-significant trend towards increased treatment failure for patients with Child’s B/C cirrhosis as well as increasing MELD score. In multivariable analysis, pre-treatment AFP ≥1000 ng/ml (HR 3.25, p<0.001) and Child’s B/C cirrhosis (HR 1.61, p<0.001) remained statistically significant predictors of treatment failure (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and Multivariable Analyses of Predictors of Treatment Failure

| Predictor | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Univariate Analysis | ||

|

| ||

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | 0.32 |

|

| ||

| Etiology of Liver Disease | ||

| Hepatitis B (vs Hepatitis C) | 0.82 (0.46–1.45) | 0.49 |

| Non-viral (vs Hepatitis C) | 1.18 (0.68–2.05) | 0.56 |

|

| ||

| Child’s Class | ||

| Child’s B cirrhosis (vs Child’s A) | 1.61 (0.99–2.61) | 0.05 |

| Child’s C cirrhosis (vs Child’s A) | 1.35 (0.63–2.90) | 0.44 |

| Child’s B/C cirrhosis (vs Child’s A) | 1.54 (0.98–2.43) | 0.06 |

|

| ||

| MELD Score (per point) | 1.05 (1.00–1.12) | 0.08 |

|

| ||

| AFP (ng/ml) | ||

| ≥20 (vs. <20) | 1.71 (1.06–2.74) | 0.03 |

| ≥100 (vs. <100) | 1.90 (1.19–3.04) | 0.007 |

| ≥500 (vs. <500) | 2.56 (1.50–4.37) | 0.001 |

| ≥1000 (vs. <1000) | 3.47 (1.93–6.24) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Number of HCC Lesions | ||

| 2–3 (vs 1) | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) | 0.76 |

| 4–5 (vs 1) | 0.98 (0.46–2.06) | 0.95 |

|

| ||

| Type of LRT Performed | ||

| TACE only (vs RFA) | 1.44 (0.52–4.01) | 0.48 |

| Combination TACE+RFA (vs RFA) | 0.94 (0.33–2.68) | 0.91 |

|

| ||

| Multivariable Analysis* | ||

|

| ||

| AFP >1000 ng/ml | 3.25 (2.95–3.58) | <0.001 |

|

| ||

| Child’s B/C cirrhosis (vs Child’s A) | 1.61 (1.36–1.90) | <0.001 |

In the multivariate model, we calculated robust sandwich estimates of standard error to account for center-level clustering

Patients with Child’s B/C cirrhosis (n=76) had Kaplan-Meier 1- and 5-year probability of treatment failure of 33.1% and 50.8% compared with 18.5% and 38.9% for patients with Child’s A cirrhosis (n=103) (p=0.06). To determine the reason behind the association between Child’s B/C cirrhosis and treatment failure, we evaluated tumor and treatment related variables based on Child’s class. We found no significant interactions between Child’s class and AFP, number of lesions, number of LRTs received, or median time to dropout from first down-staging procedure. None of the 31 Child’s A patients who dropped out had hepatic decompensation after LRT compared to 19.2% (5/26) of Child’s B patients and 36.4% (4/11) of Child’s C patients (p=0.005).

Of the 19 patients with a pre-treatment AFP ≥1000 ng/ml, 6 were never able to be down-staged, 7 dropped out due to tumor progression after initial down-staging, and 1 had successful down-staging but was ultimately not considered for LT due to psychosocial contraindications. Only 5 patients with a pre-treatment AFP ≥1000 underwent LT and 2 of these experienced post-LT HCC recurrence. These 2 patients had an AFP at LT of 32 and 473 compared with an AFP <4 ng/ml in the 3 patients without HCC recurrence. Kaplan-Meier 1- and 5-year probabilities of treatment failure were 63.9% and 75.9% for patients with a baseline AFP ≥1000 compared with 20.2% and 39.8% among patients with a pre-treatment AFP <1000 (p<0.001).

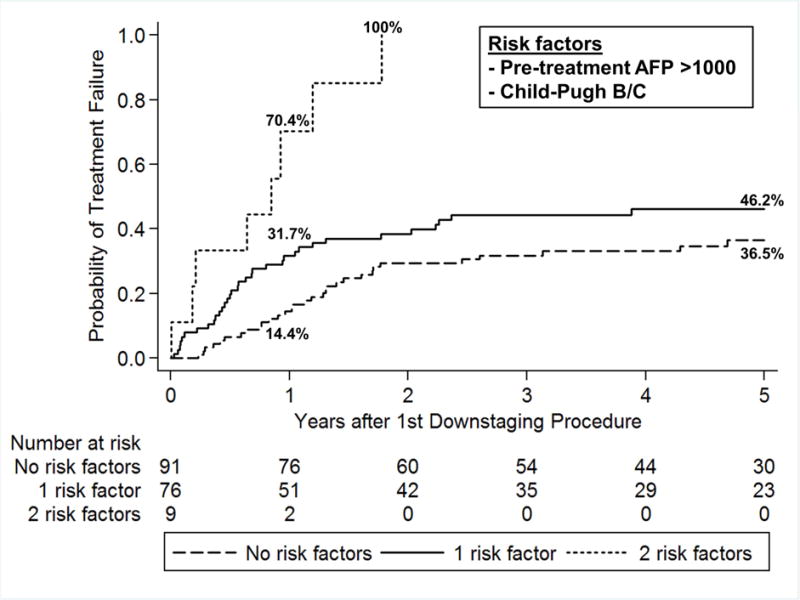

Patients with both AFP ≥1000 ng/ml and Child’s B/C cirrhosis had a 70.4% risk of treatment failure at 1 year from first down-staging procedure as compared to 31.7% with 1 risk factor and 14.4% without either risk factor (p=0.001). Patients with both risk factors had a 100% treatment failure rate within 2 years. In contrast, the probability of treatment failure at 5 years was 46.2% in patients with 1 of the 2 risk factors and 36.5% for those with neither risk factor (p=0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Probability of treatment failure from first down-staging procedure based on number of risk factors.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, we have witnessed a paradigm shift in the selection of HCC patients for LT17-19. Rather than relying solely on tumor size and number, there has been a greater emphasis on incorporating markers of tumor biology, including AFP20-21 and response to LRT22-23 in the selection scheme. In this context, high AFP and tumor progression despite LRT identify more aggressive tumors with a substantially greater risk for HCC recurrence after LT. A period of observation is required for evaluating tumor response to LRT and changes in AFP prior to LT. This concept has been filtered into the “ablate and wait” strategy for candidate selection17. Tumor down-staging is a process that combines expanded criteria with response to LRT9. It has been consistently shown that a subset of patients with initial tumor burden exceeding Milan criteria could achieve post-LT outcomes similar to that with Milan criteria. Identifying those who will likely do well after LT based on response to LRT with reduction in tumor burden to within Milan criteria underlies the fundamental principle behind using down-staging as an additional selection tool for LT9. Additionally, given that demand for organs far exceeds supply and the importance of maximizing transplant survival benefit, patients who are successfully down-staged with LRT may be more appropriate LT candidates than those with a single 2-3 cm well treated tumor and a low-risk for waitlist dropout24.

One of the criticisms of the down-staging evidence is that it is based entirely on single-center studies9,15, and may not be reproducible on a broader scale. In this first multi-center study on tumor down-staging using a uniform protocol from Region 5, we observed excellent overall 5-year post-LT survival of 80% and recurrence-free probability of 87%, as well as a very low likelihood of unfavorable histologic features in the explant. Only 7% had micro- or macro-vascular invasion, and only one patient had poorly differentiated tumor grade. These findings underscore the effectiveness of down-staging in selecting tumors with favorable biology and a good prognosis for LT. Importantly, we did not observe significant center effects in the intention-to-treat survival, post-LT survival, or HCC recurrence.

One of the objectives of this multi-center study was to assemble a large enough cohort to assess factors associated with treatment failure, which might help refine inclusion criteria for down-staging. The two factors predicting treatment failure were pre-treatment AFP ≥1000 ng/mL and Child’s class B/C cirrhosis. Of the 19 patients with a baseline AFP ≥1000 ng/ml, only 3 (16%) underwent LT after successful down-staging and did not experience post-LT HCC recurrence. This adds to the mounting evidence of high AFP as a poor prognostic marker for LT, both in terms of waitlist outcome24 as well as post-LT survival and HCC recurrence20-21. With respect to the influence of Child’s class on waitlist dropout, patients with Child’s B/C cirrhosis likely have fewer LRT options and receive less aggressive treatments given the concerns of hepatic decompensation following LRT when compared to those with Child’s A cirrhosis. Additionally, Child’s B/C patients are more likely to have liver-related death without LT regardless of whether they receive LRT.

Given that treatment failure was observed in all Child’s B/C patients with pretreatment AFP ≥1000 ng/mL, these patients should be excluded from down-staging and not be subjected to the risks attendant upon LRT, particularly hepatic decompensation or even death. For patients with Child’s A cirrhosis and a high baseline AFP ≥1000 ng/ml, we propose following the previous recommendation of a reduction in the AFP level to <500 ng/ml after LRT to be eligible for LT9,10. This is also in accordance with a recently approved UNOS national policy for HCC MELD-exception listing25. We have further demonstrated that AFP >500 ng/ml predicted HCC recurrence after LT.

A recent systematic review and pooled analysis by Parikh15 showed an aggregate down-staging success rate of 54% after excluding patients with tumor thrombus, but there are major differences in the definition of success rate in these studies. In the present series, 58% of the patients received LT, but 83% of the entire cohort was initially successfully down-staged to within Milan criteria. This high initial success rate of down-staging is likely related to the upper limits in tumor size and number for inclusion. Only one other study on down-staging defined the upper limits in tumor burden. Ravaioli13 used more liberal inclusion criteria for down-staging and showed a successful down-staging rate of 69%, but the 3-year recurrence-free survival after LT was only 71%. Rassiwala26 demonstrated a very low probability of LT of 12% when applying an “all-comers” down-staging protocol to patients with initial tumor burden exceeding Region 5 down-staging inclusion criteria. All these findings suggest that there are upper limits in tumor size and number beyond which down-staging is not likely to be successful.

The Region 5 down-staging protocol mandates a minimum observation period of 3 months to ensure disease stability following successful down-staging to within Milan criteria before proceeding with LT, but the median wait time from successful down-staging to LT in our cohort was much longer at 13 months. In this study, failure to receive LT was equally likely as a result of inability to ever achieve down-staging to Milan criteria (17%) or tumor progression after initial successful down-staging (20%). The majority of the latter group could have been transplanted in centers with shorter waitlist times. The recent UNOS policy of a mandatory 6-month wait time before granting MELD exception means that a patient with tumors successfully down-staged would have sufficient time for observing durable response to down-staging before LT even in regions with shorter wait times. It is important to emphasize that listing decision should be consistent (list for LT after successful down-staging) and not depend on regional waitlist times. Since this study came from a region with one of the longest waitlist times and highest median MELD scores at LT, the results may not be generalizable across regions. Further studies of down-staging in regions with varying waitlist times are still needed.

The type of LRT was not standardized, but determined at each center’s multidisciplinary tumor board. This is a potential limitation of this study. The majority received TACE either alone (50%) or in combination with RFA (43%), and there were no significant differences between centers in the LRT modalities. In the pooled analysis by Parikh15, there were no differences in down-staging success rate or post-LT tumor recurrence when comparing radioembolization to TACE. Another limitation of the present study is that nearly 70% were from a single center. While we observed no center-specific differences, the relatively small number of patients in centers 2 and 3 make comparisons between centers difficult to interpret and limit the generalizability of our findings.

This first multi-center study on down-staging under a uniform protocol demonstrated an excellent 5-year post-LT survival of 80% with a low rate of HCC recurrence. These results support expanding priority access to LT for patients with HCC that have been successfully down-staged. In the meantime, UNOS has recently approved the Region 5 down-staging protocol for receiving automatic HCC-MELD exception listing25. Slight refinements in the inclusion criteria for down-staging appear warranted based on the observation that all Child’s B/C patients with pre-treatment AFP ≥1000 ng/ml suffered poor outcomes when down-staging was attempted.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Health to the University of California, San Francisco Liver Center (P30 DK026743)

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- CTP

Child-Turcotte-Pugh

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HR

hazard ratio

- IQR

interquartile range

- LRT

local regional therapy

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End Stage Liver Disease

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OR

odds ratio

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

- UCSF

University of California, San Francisco

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None of the authors have any relevant potential conflicts of interest to disclose

Author Contributions: Concept and design: Mehta, Guy, Frenette, Roberts, Yao

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Mehta, Guy, Frenette, Dodge, Minteer, Osorio, Roberts, Yao

Drafting of the manuscript: Mehta, Dodge, Yao

Criticial revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Mehta, Guy, Frenette, Dodge, Minteer, Osorio, Roberts, Yao

Statistical Analysis: Mehta, Guy, Frenette, Dodge, Yao

Supervision: Osorio, Roberts, Yao

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim WR, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2012 Annual Data Report: liver. Am J Transpl. 2014;S1:69–96. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halazun KJ, Patzer RE, Rana AA, et al. Standing the test of time: outcomes of a decade of prioritizing patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:1957–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.27272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, et al. Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an international consensus conference report. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e11–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70175-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad KR, Young RS, Burra P, et al. Summary of candidate selection and expanded criteria for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a review and consensus statement. Liver transpl. 2011;S2:S81–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.22380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394–403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao FY, Fidelman N. Reassessing the boundaries of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Where do we stand with tumor down-staging? Hepatology. 2016;63:1014–25. doi: 10.1002/hep.28139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pomfret EA, Washburn K, Wald C, et al. Report of a national conference on liver allocation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Liver transpl. 2010;16:262–78. doi: 10.1002/lt.21999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas MB, Jaffe D, Choti MM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: consensus recommendations of the National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3994–4005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.7805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yao FY, Mehta N, Flemming J, et al. Downstaging of hepatocellular cancer before liver transplant: Long-term outcome compared to tumors within Milan criteria. Hepatology. 2015;61:1968–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.27752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Piscaglia F, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: results of down-staging in patients initially outside the Milan selection criteria. Am J Transpl. 2008;8:2547–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang JW, You CR, Kim CW, et al. Benefit of downsizing hepatocellular carcinoma in a liver transplant population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;31:415–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parikh ND, Waljee AK, Singal AG. Downstaging hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:1142–52. doi: 10.1002/lt.24169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edmondson H, Steiner P. Primary carcinoma of the liver: a study of 100 cases among 48,900 necropsies. Cancer. 1954;1:462–503. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195405)7:3<462::aid-cncr2820070308>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts JP, Venook A, Kerlan R, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Ablate and wait versus rapid transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:925–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta N, Yao FY. Moving past “one size (and number) fits all” in the selection of candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma for liver transplant. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1055–8. doi: 10.1002/lt.23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazzaferro V. Squaring the circle of selection and allocation in liver transplantation for HCC: An adaptive approach. Hepatology. 2016;63:1707–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.28420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duvoux C, Roudot-Thoraval F, Decaens T, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a model including alpha-fetoprotein improves the performance of Milan criteria. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:986–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hameed B, Mehta N, Sapisochin G, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein level > 1000 ng/mL as an exclusion criterion for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma meeting the Milan criteria. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:945–51. doi: 10.1002/lt.23904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto G, Herber S, Heise M, et al. Response to transarterial chemoembolization as a biological selection criterion for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1260–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai Q, Avolio AW, Graziadei I, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumor progression after locoregional therapy as predictors of hepatocellular cancer recurrence and death after transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1108–18. doi: 10.1002/lt.23706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta N, Dodge JL, Goel A, et al. Identification of liver transplant candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma and a very low dropout risk: implications for the current organ allocation policy. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1343–53. doi: 10.1002/lt.23753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.OPTN/UNOS policy. accessed 6/1/17 at https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/

- 26.Rassiwala J, Mehta N, Dodge JL, et al. Are there upper limits in tumor burden for successful down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma to liver transplant? Hepatology. 2016;64(Suppl):75A. doi: 10.1002/hep.30570. [Abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]