Abstract

The diagnosis, treatment, and medical late effects of childhood cancer may alter the psychosocial trajectory of survivors across their life course. This review of the literature focuses on mental health symptoms, achievement of social milestones, socioeconomic attainment, and risky health behaviors in survivors of childhood cancer. Results suggest that although most survivors are psychologically well adjusted, survivors are at risk for anxiety and depression compared with siblings. Although the absolute risk of suicide ideation and post-traumatic stress symptoms is low, adult survivors are at increased risk compared with controls. Moreover, young adult survivors are at risk for delayed psychosexual development, lower rates of marriage or cohabitation, and nonindependent living. Survivors’ socioeconomic attainment also is reduced, with fewer survivors graduating college and gaining full-time employment. Despite risk for late health-related complications, survivors of childhood cancer generally engage in risky health behaviors at rates similar to or only slightly lower than siblings and peers. CNS tumors and CNS-directed therapies are salient risk factors for poor psychosocial outcomes. In addition, physical health morbidities resulting from cancer-directed therapies are associated with worse psychosocial functioning. Several studies support the effectiveness of cognitive and behavioral interventions to treat psychological symptoms as well as to modify health behaviors. Additional randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy and long-term outcomes of intervention efforts. Future research should focus on the identification of potential genetic predispositions related to psychosocial outcomes to provide opportunities for preventive interventions among survivors of childhood cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for disrupted psychosocial development secondary to their primary diagnosis, treatment, and medical late effects. The immediate impact of a cancer diagnosis and treatment may result in acute distress and/or adjustment difficulties, maladaptive coping, missed educational opportunities, and reduced social engagement with peers. The psychosocial trajectory of survivors may be additionally offset by the emergence of treatment-induced medical late effects in adolescence and adulthood. Given the protracted time course spanning diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship, the potential psychosocial consequences of childhood cancer are considerable. Although most survivors are psychologically well adjusted, difficulties have been reported related to the development of mental health symptoms, failure to meet expected social milestones, reduced educational achievement and vocational attainment, and engagement in maladaptive health behaviors. The primary objectives of this paper are to review research related to psychosocial outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer, with an emphasis on risk factors for adverse outcomes, and to highlight potentially efficacious interventions to improve psychosocial outcomes for survivors.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SYMPTOMS

Epidemiologic and large cohort studies indicate that survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for psychological impairments compared with their peers1,2; however, the majority of survivors, 75% to 80% in most studies, do not experience significant psychological impairments.1,2 Moreover, studies of psychological problems in survivors tend to focus on prevalence of psychological symptoms without assessing associated impairments or the prevalence of mental disorders. Studies using both symptom rating scales and diagnostic interviews suggest many survivors of childhood cancer with elevated symptoms may not have mental health disorders,3,4 which is consistent with epidemiologic studies showing survivors are more likely to use mental health services but not more likely to have severe psychopathology.5 Moreover, beyond the absence of psychological symptoms, a substantial proportion of survivors report that cancer had a limited or even positive impact on their adjustment.6

Nevertheless, survivors of childhood cancer as a whole are at risk for adverse psychological outcomes. Children and adolescent survivors are significantly more likely to have symptoms of anxiety and depression, inattention, antisocial behavior, and impaired social competence compared with siblings.7 Increased prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms have been reported in adult survivors of childhood cancer many years after completion of therapy,1,2 as have post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) and suicide ideation (SI).8,9 Although the absolute risk of SI and PTSS were low (6% to 8% for SI; 9% for PTSS), adult survivors were at increased risk compared with controls. Importantly, it remains unclear if risk of SI extends to increased risk for suicide attempts or deaths.10

Several factors have been associated with adverse psychological symptoms in survivors, including low income, lower education, female sex, disability status, and unmarried status.2 However, the direction of effects is unclear, as these factors may contribute to, or be the consequences of, mental health problems. Poor physical health, including chronic health conditions, pain, and disfigurement, are consistently associated with poor mental health outcomes in survivors.1,7,9,11

With mental health strongly tied to childhood cancer survivors’ physical health, it is not surprising that cancer treatments associated with medical late effects are associated with psychological adjustment. CNS-directed therapies, especially cranial radiation therapy (CRT) have been associated with poor adjustment, and CNS tumor survivors overall are at high risk for poor adjustment.2,7,11 Intensive chemotherapy regimens and those including alkylating agents also have been associated with psychological symptoms.2,7,11 Survivors of bone tumors are at risk for psychosocial problems, likely reflecting the impact of physical mobility problems and pain on adjustment.2,11

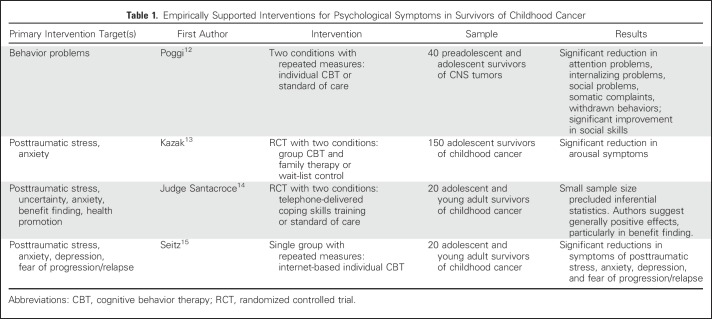

Little research has focused on the implementation and evaluation of interventions targeting psychological symptoms in survivors of childhood cancer (Table 1),12-15 and most existing studies are limited by small sample sizes, lack of appropriate comparison groups, and diagnostically heterogeneous samples. However, results seem to suggest that tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy can improve PTSS and anxiety as well as behavior problems in survivors of CNS tumors.

Table 1.

Empirically Supported Interventions for Psychological Symptoms in Survivors of Childhood Cancer

SOCIAL OUTCOMES

In childhood, survivors are at risk for social difficulties marked by poor peer acceptance, isolation, and diminished leadership roles. Difficulties in the social arena are most commonly observed among survivors of CNS tumors and CNS-directed therapies.16 Critical tasks for survivors include the development of social relationships and establishing independence from primary caregivers. Attainment of these developmental tasks may be complicated by survivors’ treatment history and/or the emergence of late effects. In general, results from large cohort studies suggest that survivors have lower rates of marriage or cohabitation compared with siblings,17 national cancer registry data,18 and general population data.17 Predictors of not partnering include CNS tumor diagnosis,17,18 CNS-directed therapies,17 and male sex.18 Rates of separation or divorce appear largely equivocal between survivors and comparison groups.18

Successful negotiation of psychosexual milestones has been increasingly recognized as an important social outcome for survivors of childhood cancer. Female survivors have reported lower sexual function, interest, desire, arousal, satisfaction, and activity compared with female siblings,19 and male survivors have reported significantly less sexual activity and 2.6-fold higher relative risk of erectile dysfunction compared with male siblings.20 Delayed achievement of psychosexual milestones, including dating, masturbation, and sexual intercourse, also have been reported among survivors.21 Higher neurotoxic treatment intensity seems to be a significant risk factor for delayed and/or impaired psychosexual development.19 Importantly, some data indicate no differences in risky sexual behaviors between adolescent survivors and siblings,22 suggesting more pronounced psychosexual difficulties may not emerge until young adulthood, when the development of intimate relationships is a more salient social goal.

The ability of survivors to live independently serves an important indicator of adult autonomy. Unfortunately, survivors are twice as likely to live dependently compared with their siblings.23 Risk factors for nonindependent living include CNS tumor diagnosis, CRT, poor physical functioning, and neurocognitive problems.23 The ability of survivors to live independently may be additionally complicated by treatment-related morbidities, including hearing impairment and vison loss.24,25

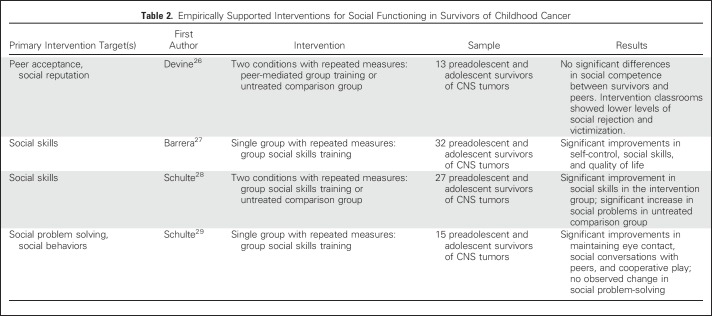

The majority of intervention research related to social functioning has involved social skills training among child and adolescent survivors of CNS tumors (Table 2).26-29 This focused effort is prudent, given the heightened risk for adverse social outcomes among survivors of CNS tumors as well the importance of early intervention to offset later deleterious social outcomes. However, these studies have been limited by small sample sizes, relatively modest effects, and discrepancies in outcomes on the basis of parent versus survivor self-report. Future work is needed to understand the long-term impact of these interventions as well as to promote social integration and independence among adult survivors of childhood cancer.

Table 2.

Empirically Supported Interventions for Social Functioning in Survivors of Childhood Cancer

SOCIOECONOMIC ATTAINMENT

Educational Achievement

School-age patients with cancer may miss significant educational opportunities because of their illness and treatment. This may result in survivors requiring additional educational support or grade retention.30 A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study indicated that 23% of survivors had a history of special education services compared with 8% of siblings.30 Neurocognitive deficits contribute significantly to the educational difficulties experienced by survivors.31 Although survivors of CNS tumors and leukemia are generally at greatest risk for low educational achievement, elevated risk of not graduating high school also has been observed among survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and neuroblastoma.30 Among survivors who did not receive CNS-directed therapies, the mechanisms underlying poor attainment have not fully been elucidated but may include individual variation in response to cancer-directed therapies, treatment-related late effects,32 or changes in teacher/peer behavior after school reentry.33 Of note, some studies suggest that subgroups of survivors achieve educational outcomes comparable to their peers, and reports from European countries indicate that survivors may surpass expected outcomes in the general population.34 Enhancing educational opportunities and outcomes is critical for survivors of childhood cancer, because success in the academic arena sets the stage for later vocational opportunities.

Vocational Attainment

A recent meta-analysis revealed that the likelihood of unemployment among survivors of childhood cancer is 50% greater than observed in the general population35 but may be improving in comparison with earlier studies.36 Importantly, vocational outcomes vary by geographic region. Specifically, survivors from the United States and Canada appear to be at greater risk of unemployment than survivors in Europe or Asia.35 Risk factors for unemployment include diagnosis of a CNS tumor, younger age at diagnosis, treatment with CRT, cancer-related late effects, and female sex. Employment has a direct impact on income and, in the United States, health insurance. Studies have consistently reported lower overall income among survivors compared with the general population, particularly among survivors of CNS tumors or those treated with CRT.37-39 In the United States, survivors often have difficulty acquiring health insurance,40 and a larger proportion are enrolled in federal programs that provide disability benefits compared with adults without a cancer history.41 In addition, a recent report from the Netherlands indicated that survivors use more social benefits for disability compared with the general population.42

The health implications of adverse socioeconomic outcomes for survivors of childhood cancer are considerable.43 Survivors with lower educational attainment and lower household income are at risk for not receiving recommended long-term follow-up care.44 Survivors who report financial burden, especially those who spend a high percentage of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs, are more likely to defer care for a medical problem.45 Restricted access to health insurance also has been associated with lower use of survivor-focused and general preventative health care.46 Taken together, these data suggest that survivors may experience financial toxicity or burden as a result of their cancer and its treatment. A report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study indicated that 14% and 37% of adult survivors experience severe and moderate financial hardship, respectively.47 Lower educational attainment, lower household income, and the development of chronic health conditions were associated with increased risk of severe hardship. Additional research is needed to better characterize the prevalence and consequences of financial toxicity.48

Despite risk of reduced vocational outcomes and associated financial and health consequences, we are unaware of interventions that have been developed/evaluated among survivors. Vocational rehabilitation efforts have been studied in other populations, including adults with traumatic brain injury, and similar approaches may be beneficial in survivors of childhood cancer. Strauser et al49 reported that although few young adult survivors of cancer were enrolled in state or federal rehabilitation programs, survivors who received job search assistance and on-the-job support were four times more likely to be employed after receipt of such services.

HEALTH BEHAVIORS

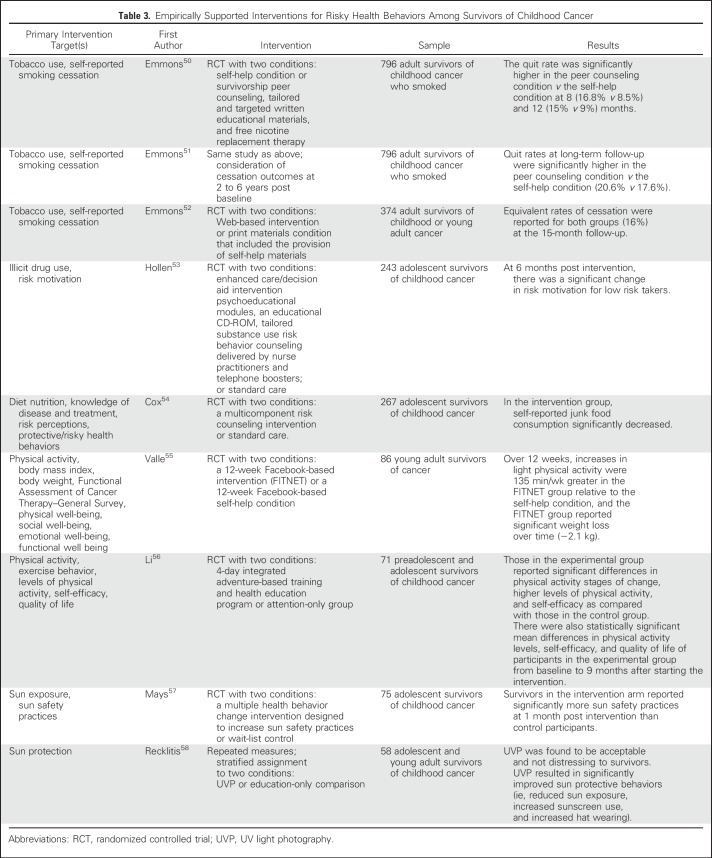

Psychological symptoms and poor socioeconomic outcomes place survivors at risk for engagement in risky health behaviors. Importantly, risky behavior exacerbates existing health vulnerabilities and places survivors of childhood cancer at risk for adverse health outcomes. Despite these risks, survivors of childhood cancer generally engage in risky health behaviors at rates similar to or only slightly lower than siblings and peers. Few mechanisms exist for reducing risk of second cancers in survivors, but modifying risky behavior remains one such option. Although the number of randomized trials considering risky health behavior in survivors is few (Table 3), overall results confirm that health behaviors are modifiable and behavioral counseling and/or psychoeducation can result in desired behavior change.50-58

Table 3.

Empirically Supported Interventions for Risky Health Behaviors Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer

Tobacco Use

Cigarette smoking has been linked to variety of adverse health outcomes, including neoplasia, cardiac, pulmonary, and other health problems. Cancer-directed therapies often result in organ compromise, which may be additionally exacerbated by tobacco use.59 Some 19% to 22% of survivors report smoking within the past 30 days,60 and 8.3% of males are smokeless tobacco users.61 However, these prevalence estimates may under- or overestimate the actual proportion of survivors who are tobacco users, because they are based on self-report and sensitive to secular trends. Survivors reporting psychological distress or heavy drinking are more likely to be current smokers, and those with higher income, higher education, and exposure to CRT are less likely to use tobacco.62 Smoking is particularly concerning among survivors, because they are less likely to successfully quit smoking after initiation compared with their peers.63

Marijuana (Cannabis) and Illicit Drug Use

As with tobacco use, smoking marijuana has been associated with pulmonary complications, whereas cocaine and methamphetamine use has been associated with cardiac problems in survivors of childhood cancer.64 Fortunately, prevalence estimates of cocaine/crack use remain low (eg, 0.6%).65 In contrast, estimates of marijuana use range from 10% to 12%,65,66 but with increasing legalization (both medical and recreational), these rates are climbing. Risk factors for marijuana and other illicit drug use include older age, male sex, lower resiliency to peer influences, depressive symptoms, higher socioeconomic status, and drug use among friends and household members.53

Alcohol Use

Excessive alcohol consumption has been associated with a number of malignancies, including oropharyngeal, esophageal, liver, and stomach cancers. Data from the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study indicated that frequent alcohol consumption occurred more often among survivors relative to the general population (22% v 12%), with similar patterns observed in monthly binge drinking (18% v 9%). Predictors of risky drinking include younger age, male sex, lower educational attainment, psychological stress, increased life stressors and dissatisfaction, activity limitations, and perceptions of poor health. Across studies, disease and treatments affecting the CNS have been associated with lower risk of alcohol use.

Diet, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

Healthy nutrition, diet, and physical activity can mitigate many late effects of cancer treatment, including obesity, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and osteoporosis. Unfortunately, many survivors of childhood cancer do not meet recommended dietary guidelines, with 54% exceeding daily caloric consumption requirements,67 and only 4%, 19%, 24%, and 29% of survivors meet guidelines for vitamin D, sodium, calcium, and saturated fat intake, respectively.68 Furthermore, 52% of adult survivors of childhood cancer do not meet physical activity guidelines.69 Consistent with population factors, predictors of healthy diet among survivors include younger age, female sex, higher education, higher socioeconomic status, greater social support, and fewer depressive symptoms. Although female sex, low parent education, CRT, and mobility restrictions predict low physical activity in adolescence, poor diet and low self-esteem in adolescence have been associated with nonadherence to physical activity guidelines in adults.70 Although empirical support for diet, nutritional, and physical activity interventions among survivors remains in its nascency, preliminary evidence suggests that psychoeducational and physical activity interventions have the potential to improve these behaviors.

Sun Exposure

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most prevalent subsequent malignant neoplasm in survivors of childhood cancer.71 Because UV radiation from the sun is a well-recognized cause of skin cancer, efforts have been made to understand sun exposure and related behaviors in survivors. A minority of survivors of childhood cancer always or often use sunscreen (44%) or sun-protective clothing (18%), wear a hat when outside (36%), limit sun exposure (35%), stay in the shade (32%), or complete recommended skin examinations (33%).72 Older attained age and CNS tumors have been associated with increased engagement in sun protection, whereas overweight or obese survivors were less likely to report receiving a skin examination.72

Risky Sexual Behavior

Risky sexual behavior has recently been included in the cluster of risky behaviors studied among survivors, in part because of its association with genital human papillomavirus (HPV) and anogenital and oropharyngeal cancers. Although prevention of specific HPV-related cancers can occur via the HPV vaccine, survivors of childhood cancer initiate the HPV vaccine at rates significantly lower than their population peers (23.8% v 40.5%).73 Because survivors are more likely to experience an HPV-related cancer in adulthood,74 a better understanding of sexual behavior in survivors is needed.22

CONCLUSION

As the population of survivors of childhood cancer continues to grow, research into their long-term psychosocial adjustment will be critical. Although most studies to date are limited by cross-sectional designs, tumor location within the CNS and CNS-directed therapies have emerged as salient risk factors for poor psychosocial outcomes. As front-line therapeutic protocols aim to reduce potentially neurotoxic treatment exposures (eg, reduced-dose craniospinal radiation for subtypes of medulloblastoma, elimination of prophylactic CRT for acute lymphoblastic leukemia), continued follow-up to assess long-term outcomes is needed to determine if an expected reduction in psychosocial morbidities occurs. In addition, the impact of therapeutic changes in other groups of survivors (ie, limb-sparing approaches in survivors of bone tumor) should be examined in relation to psychological outcomes. Unfortunately, recent research suggests that changes to front-line therapies in more contemporarily treated cohorts of survivors have not yielded reductions in poor mental health, pain, or cancer-related anxiety in adult survivors.75 Incorporation of mental health and behavioral measures in established and new cohort studies will support research across a broader range of survivors and new cancer therapies. In addition, longitudinal studies will serve to enhance understanding of the time course of these outcomes as well as specific temporal causes. Assessing psychiatric diagnoses and impairment because of psychological symptoms in outcomes research will significantly improve our understanding of survivors’ mental health needs and help inform the development of intervention programs to meet those unique needs. Although most intervention efforts to date have been small, many suggest potential efficacy and should begin to be incorporated and disseminated as part of standard clinical care.

An important area of future research centers on the identification of potential genetic predispositions related to psychosocial outcomes among survivors of childhood cancer. Data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study indicated that among survivors of medulloblastoma, those with homozygous GSTM1 gene deletion reported greater symptoms of anxiety, depression, and global distress compared with survivors of medulloblastoma with the GSTM1 non-null genotype.76 This work could be extended to outcomes such as post-traumatic stress disorder, where evidence supporting a genetic predisposition has been reported in other populations. However, among survivors, understanding interactions between therapeutic exposures that place survivors at risk for adverse outcomes and genetic predispositions will be critical. Moreover, pharmacogenetics studies may be useful to promote understanding of survivor engagement in risky health behaviors, such as tobacco and alcohol abuse (eg, dopamine receptor gene DRD2). Identification of survivors who are at risk for adverse psychosocial outcomes secondary to genetic variations will provide opportunities for preventative interventions.

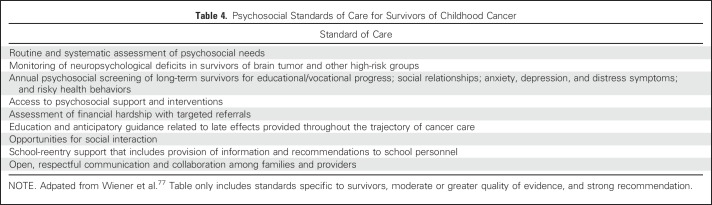

Timely identification of psychosocial issues is critical to offset potential deleterious effects across the developmental life course of survivors. Recent evidence-based standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer identify services that are essential for comprehensive care (Table 4).77 Unfortunately, many pediatric oncology programs lack the multidisciplinary teams necessary to implement the full set of standards. Despite this potential barrier, psychosocial programming must be prioritized in pediatric oncology and survivorship settings as a means of promoting prosocial development and physical and mental health outcomes across the cancer continuum.

Table 4.

Psychosocial Standards of Care for Survivors of Childhood Cancer

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant No. CA21765 (C. Roberts, Principal Investigator).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Psychological Symptoms, Social Outcomes, Socioeconomic Attainment, and Health Behaviors Among Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Current State of the Literature

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Tara M. Brinkman

No relationship to disclose

Christopher J. Recklitis

Research Funding: Merck Research Laboratories (Inst)

Gisela Michel

No relationship to disclose

Martha A. Grootenhuis

No relationship to disclose

James L. Klosky

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Michel G, Rebholz CE, von der Weid NX, et al. : Psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer: The Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor study. J Clin Oncol 28:1740-1748, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. : Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 27:2396-2404, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recklitis CJ, Blackmon JE, Chang G: Validity of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) for identifying depression and anxiety in young adult cancer survivors: Comparison with a Structured Clinical Diagnostic Interview. Psychol Assess 29:1189-1200, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phipps S, Klosky JL, Long A, et al. : Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: Has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? J Clin Oncol 32:641-646, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross L, Johansen C, Dalton SO, et al. : Psychiatric hospitalizations among survivors of cancer in childhood or adolescence. N Engl J Med 349:650-657, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tillery R, Howard Sharp KM, Okado Y, et al. : Profiles of resilience and growth in youth with cancer and healthy comparisons. J Pediatr Psychol 41:290-297, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkman TM, Li C, Vannatta K, et al. : Behavioral, social, and emotional symptom comorbidities and profiles in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 34:3417-3425, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuber ML, Meeske KA, Krull KR, et al. : Prevalence and predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Pediatrics 125:e1124-e1134, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkman TM, Zhang N, Recklitis CJ, et al. : Suicide ideation and associated mortality in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer 120:271-277, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gunnes MW, Lie RT, Bjørge T, et al. : Suicide and violent deaths in survivors of cancer in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood: A national cohort study. Int J Cancer 140:575-580, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Agostino NM, Edelstein K, Zhang N, et al. : Comorbid symptoms of emotional distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer 122:3215-3224, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poggi G, Liscio M, Pastore V, et al. : Psychological intervention in young brain tumor survivors: The efficacy of the cognitive behavioural approach. Disabil Rehabil 31:1066-1073, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kazak AE, Alderfer MA, Streisand R, et al. : Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: A randomized clinical trial. J Fam Psychol 18:493-504, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Judge Santacroce S, Asmus K, Kadan-Lottick N, et al. : Feasibility and preliminary outcomes from a pilot study of coping skills training for adolescent--young adult survivors of childhood cancer and their parents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 27:10-20, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seitz DC, Knaevelsrud C, Duran G, et al. : Efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioral intervention for long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: A pilot study. Support Care Cancer 22:2075-2083, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, Wells RJ, et al. : Intensity of CNS treatment for pediatric cancer: Prediction of social outcomes in survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 49:716-722, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janson C, Leisenring W, Cox C, et al. : Predictors of marriage and divorce in adult survivors of childhood cancers: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:2626-2635, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch SV, Kejs AM, Engholm G, et al. : Marriage and divorce among childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33:500-505, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford JS, Kawashima T, Whitton J, et al. : Psychosexual functioning among adult female survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 32:3126-3136, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritenour CW, Seidel KD, Leisenring W, et al. : Erectile dysfunction in male survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Sex Med 13:945-954, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJ, et al. : Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 17:506-511, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klosky JL, Foster RH, Li Z, et al. : Risky sexual behavior in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Psychol 33:868-877, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kunin-Batson A, Kadan-Lottick N, Zhu L, et al. : Predictors of independent living status in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:1197-1203, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brinkman TM, Bass JK, Li Z, et al. : Treatment-induced hearing loss and adult social outcomes in survivors of childhood CNS and non-CNS solid tumors: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Cancer 121:4053-4061, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Blank PM, Fisher MJ, Lu L, et al. : Impact of vision loss among survivors of childhood central nervous system astroglial tumors. Cancer 122:730-739, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devine KA, Bukowski WM, Sahler OJ, et al. : Social competence in childhood brain tumor survivors: Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a peer-mediated intervention. J Dev Behav Pediatr 37:475-482, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barrera M, Schulte F: A group social skills intervention program for survivors of childhood brain tumors. J Pediatr Psychol 34:1108-1118, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulte F, Bartels U, Barrera M: A pilot study evaluating the efficacy of a group social skills program for survivors of childhood central nervous system tumors using a comparison group and teacher reports. Psychooncology 23:597-600, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulte F, Vannatta K, Barrera M: Social problem solving and social performance after a group social skills intervention for childhood brain tumor survivors. Psychooncology 23:183-189, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitby PA, Robison LL, Whitton JA, et al. : Utilization of special education services and educational attainment among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 97:1115-1126, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krull KR, Hardy KK, Kahalley LS, et al. : Neurocognitive outcomes and interventions in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 36:2181-2189, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gurney JG, Tersak JM, Ness KK, et al. : Hearing loss, quality of life, and academic problems in long-term neuroblastoma survivors: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Pediatrics 120:e1229-e1236, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reiter-Purtill J, Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA, et al. : A controlled longitudinal study of the social functioning of children who completed treatment of cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 25:467-473, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dumas A, Berger C, Auquier P, et al. : Educational and occupational outcomes of childhood cancer survivors 30 years after diagnosis: A French cohort study. Br J Cancer 114:1060-1068, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mader L, Roser K, Michel G: Unemployment following childhood cancer—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dtsch Arztebl Int (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, van Dijk FJ: Adult survivors of childhood cancer and unemployment: A metaanalysis. Cancer 107:1-11, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunnes MW, Lie RT, Bjørge T, et al. : Economic independence in survivors of cancer diagnosed at a young age: A Norwegian national cohort study. Cancer 122:3873-3882, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wengenroth L, Sommer G, Schindler M, et al. : Income in adult survivors of childhood cancer. PLoS One 11:e0155546, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boman KK, Lindblad F, Hjern A: Long-term outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in Sweden: A population-based study of education, employment, and income. Cancer 116:1385-1391, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park ER, Li FP, Liu Y, et al. : Health insurance coverage in survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 23:9187-9197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirchhoff AC, Parsons HM, Kuhlthau KA, et al. : Supplemental security income and social security disability insurance coverage among long-term childhood cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 107:djv057, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Font-Gonzalez A, Feijen EL, Sieswerda E, et al. : Social outcomes in adult survivors of childhood cancer compared to the general population: Linkage of a cohort with population registers. Psychooncology 25:933-941, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hudson MM, Oeffinger KC, Jones K, et al. : Age-dependent changes in health status in the Childhood Cancer Survivor cohort. J Clin Oncol 33:479-491, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Casillas J, Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, et al. : Identifying predictors of longitudinal decline in the level of medical care received by adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Health Serv Res 50:1021-1042, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al. : Financial burden in survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 35:3474-3481, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casillas J, Castellino SM, Hudson MM, et al. : Impact of insurance type on survivor-focused and general preventive health care utilization in adult survivors of childhood cancer: The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Cancer 117:1966-1975, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Huang IC, Bhakta N, Brinkman TM, et al: Effects of financial hardship on symptoms and quality of life among long-term adult survivors of childhood cancer: Results from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Presented at 8th Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research Conference, Washington, DC, June 16-18, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nathan PC, Henderson TO, Kirchhoff AC, et al. : Financial hardship and the economic impact of childhood cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol 36:2198-2205, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strauser D, Feuerstein M, Chan F, et al. : Vocational services associated with competitive employment in 18-25 year old cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 4:179-186, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Park E, et al. : Peer-delivered smoking counseling for childhood cancer survivors increases rate of cessation: The partnership for health study. J Clin Oncol 23:6516-6523, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Mertens A, et al. : Long-term smoking cessation outcomes among childhood cancer survivors in the Partnership for Health Study. J Clin Oncol 27:52-60, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Sprunck-Harrild K, et al. : Partnership for health-2, a web-based versus print smoking cessation intervention for childhood and young adult cancer survivors: Randomized comparative effectiveness study. J Med Internet Res 15:e218, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hollen PJ, Tyc VL, Donnangelo SF, et al. : A substance use decision aid for medically at-risk adolescents: Results of a randomized controlled trial for cancer-surviving adolescents. Cancer Nurs 36:355-367, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cox CL, McLaughlin RA, Rai SN, et al. : Adolescent survivors: A secondary analysis of a clinical trial targeting behavior change. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45:144-154, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, et al. : A randomized trial of a Facebook-based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 7:355-368, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li HC, Chung OK, Ho KY, et al. : Effectiveness of an integrated adventure-based training and health education program in promoting regular physical activity among childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 22:2601-2610, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mays D, Black JD, Mosher RB, et al. : Improving short-term sun safety practices among adolescent survivors of childhood cancer: A randomized controlled efficacy trial. J Cancer Surviv 5:247-254, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Recklitis CJ, Bakan J, Werchniak AE, et al. : Using appearance-based messages to increase sun protection in adolescent young adult cancer survivors: A pilot study of ultraviolet light photography. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 6:477-481, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klosky JL, Tyc VL, Garces-Webb DM, et al. : Emerging issues in smoking among adolescent and adult cancer survivors: A comprehensive review. Cancer 110:2408-2419, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marjerrison S, Hendershot E, Empringham B, et al. : Smoking, binge drinking, and drug use among childhood cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63:1254-1263, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klosky JL, Hum AM, Zhang N, et al. : Smokeless and dual tobacco use among males surviving childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 22:1025-1029, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gibson TM, Liu W, Armstrong GT, et al. : Longitudinal smoking patterns in survivors of childhood cancer: An update from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 121:4035-4043, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Larcombe I, Mott M, Hunt L: Lifestyle behaviours of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer 87:1204-1209, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tyc VL, Klosky JL: Lifestyle factors and health risk behaviors, in Mucci GA, Torno LR (eds): Handbook of Long Term Care of the Childhood Cancer Survivor. New York, NY, Springer, 2015, pp 325-346. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klosky JL, Howell CR, Li Z, et al. : Risky health behavior among adolescents in the childhood cancer survivor study cohort. J Pediatr Psychol 37:634-646, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rebholz CE, Rueegg CS, Michel G, et al. : Clustering of health behaviours in adult survivors of childhood cancer and the general population. Br J Cancer 107:234-242, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Love E, Schneiderman JE, Stephens D, et al. : A cross-sectional study of overweight in pediatric survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Pediatr Blood Cancer 57:1204-1209, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang FF, Saltzman E, Kelly MJ, et al. : Comparison of childhood cancer survivors’ nutritional intake with US dietary guidelines. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:1461-1467, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, et al. : Predictors of inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 115:1984-1994, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Devine KA, Mertens AC, Whitton JA, et al. : Factors associated with physical activity among adolescent and young adult survivors of early childhood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study (CCSS). Psychooncology 27:613-619, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Turcotte LM, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al. : Temporal trends in treatment and subsequent neoplasm risk among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer, 1970-2015. JAMA 317:814-824, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Krull KR, Annett RD, Pan Z, et al. : Neurocognitive functioning and health-related behaviours in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Eur J Cancer 47:1380-1388, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Klosky JL, Hudson MM, Chen Y, et al. : Human papillomavirus vaccination rates in young cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 35:3582-3590, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ojha RP, Tota JE, Offutt-Powell TN, et al. : Human papillomavirus-associated subsequent malignancies among long-term survivors of pediatric and young adult cancers. PLoS One 8:e70349, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ness KK, Hudson MM, Jones KE, et al. : Effect of temporal changes in therapeutic exposure on self-reported health status in childhood cancer survivors. Ann Intern Med 166:89-98, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brackett J, Krull KR, Scheurer ME, et al. : Antioxidant enzyme polymorphisms and neuropsychological outcomes in medulloblastoma survivors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuro-oncol 14:1018-1025, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, et al. : Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: An introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62:S419-S424, 2015. (suppl 5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]