Abstract

Introduction

The inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) sirolimus and everolimus are used as immunosuppressants after organ transplantation in combination with calcineurin inhibitors, but also as proliferation signal inhibitors coated on drug eluting stents and in cancer therapy. Notwithstanding their related chemical structures both have distinct pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and toxicodynamic properties.

Areas covered

The additional hydroxyethyl group at the C(40) of the everolimus molecule results in different tissue and subcellular distribution, different affinities to active drug transporters and drug metabolizing enzymes as well as differences in drug-target protein interactions including a much higher potency in terms of interacting with the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) than sirolimus. Said mechanistic differences as well as differences found in clinical trials in transplant patients are reviewed.

Expert opinion

In comparison to sirolimus, everolimus has higher bioavailability, a shorter terminal half-life, different blood metabolite patterns, the potential to antagonize the negative effects of calcineurin inhibitors on neuronal and kidney cell metabolism (which sirolimus enhances), the ability to stimulate mitochondrial oxidation (which sirolimus inhibits), and to reduce vascular inflammation to a greater extent. A head-to-head, randomized trial comparing the safety and tolerability of these two mTOR inhibitors in solid organ transplant recipients is merited.

Keywords: Everolimus, sirolimus, comparison, nephrotoxicity, neuronal metabolism, mitochondria, pharmacokinetics, drug metabolism, vascular inflammation, mTORC2

1. Introduction

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor class is now well-established as part of the immunosuppressive armamentarium following solid organ transplantation, which have been extensively explored in kidney [1, 2], in heart [3], as well as in liver transplantation [4–6]. In addition, mTOR inhibitors are used as proliferation signal inhibitors in cancer therapy [7,8] and coated on drug-eluting stents [9,10].

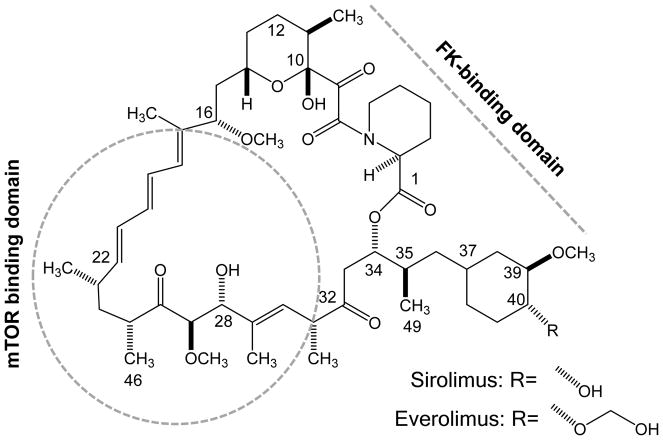

The two mTOR inhibitors that are approved in transplantation in the United States and most European countries, everolimus and sirolimus, are macrolide derivatives with related structure, which exert potent immunosuppressant and anti-proliferative effects [11,12]. Everolimus is the 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl) derivative of sirolimus [13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chemical structures of everolimus and sirolimus.

Numbering of the molecule follows the IUPAC nomenclature [14]. Regions of the macrolide ring binding to mTOR and FK-binding proteins, the so-called mTOR binding domain and FK-binding protein (FKPB)- binding domain [15], are marked.

Notwithstanding the structural relationship, there are substantial pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and toxicodynamic differences.

2. Mechanism of Action: Interactions with the mTOR Pathway

One of the major limitations of the calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) cyclosporine and tacrolimus, which nowadays are the cornerstones of most immunosuppressive protocols after transplantation, is their narrow therapeutic index. One strategy to expand the therapeutic index of a CNI-based immunosuppressive drug regimen is to combine immunosuppressive agents that interact in a synergistic fashion and thereby allow for dose reduction of each of the combination partners. Such a strategy has the benefit of reducing toxicity while maintaining immunosuppressive potency [2]. The inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) sirolimus and everolimus synergistically enhance the immunosuppressive activity of CNIs [16,17]. Both drugs act by forming a complex with the FK binding protein (FKBP-12), which binds with high affinity to the kinase mTOR [18,19]. This interrupts the mTOR intracellular signaling pathway, which is pivotal to multiple processes including, but not limited to, cell growth and proliferation, cellular metabolism and angiogenesis [17–23].

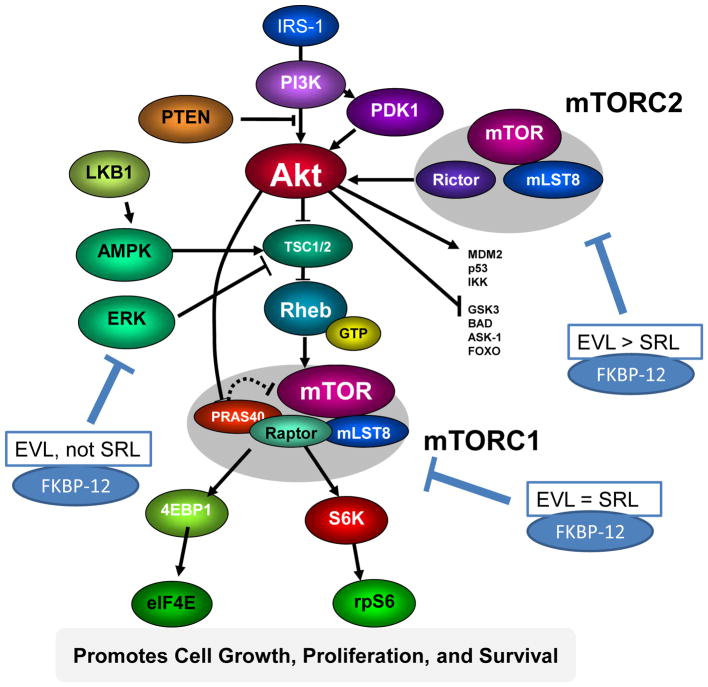

Although binding of everolimus to FKBP-12 is approximately 3-fold weaker than that of sirolimus [19], everolimus blood trough concentrations targeted in transplant patients are typically lower than for sirolimus (3–8 ng/mL versus 4–20 ng/mL [24–26]). Functionally, an FK-binding domain and an mTOR-binding domain have been identified [15] (Figure 1). As these regions of the sirolimus and everolimus molecules are structurally similar, it has been hypothesized that both molecules have the same effects on the mTOR pathway. However, in primary human aortic endothelial cells, Jin et al. [26] provided evidence that this assumption is not entirely correct and that there are significant pharmacodynamic differences. In this study, the effects of sirolimus and everolimus on the HLA I-induced m-TOR signaling pathways was studied. Importantly, equi-effective concentrations based on the aforementioned trough blood concentrations typically maintained in transplant patients were compared. Like sirolimus, everolimus inhibited mTOR complex-1 (mTORC1) by dissociation of Raptor from mTORC1 thus inhibiting phosphorylation of mTOR and downstream of p70SK and S6RP. Nevertheless, at the clinically relevant concentrations tested, everolimus was much more effective in inhibiting class-I-stimulated mTORC2 activation by dissociating Rictor and Sin1 from mTOR. This included more effective inhibition of class-I-stimulated AKT phosphorylation and inhibition of ERK phosphorylation, an ability that, remarkably, sirolimus lacked [26]. mTORC2 plays an important role in endothelial cell function and changes of mTORC2 signaling are likely to affect transplant vasculopathy. The results of this study suggest a better therapeutic effect than sirolimus in preventing chronic antibody-mediated rejection [26]. The distinct effects of everolimus and sirolimus on the mTOR pathway are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distinct effects of everolimus and sirolimus on the mTOR pathway.

The figure is based on data from [15,22,23,26]. The serine–threonine kinase mTOR plays a key role in, among others, the regulation of cell proliferation, cell metabolism (including glycolysis) and protein synthesis. It forms two complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2. Sirolimus and everolimus bind to FKBP12 [15] and then this complex inhibits activation of mTORC1 by dissociating Raptor from mTORC1. mTORC2 is not inhibited directly by the sirolimus/FKBP-12 complex. Nevertheless, but prolonged sirolimus treatment may reduce mTORC2 activity. However, as shown in [26], everolimus is markedly more potent than sirolimus in inhibiting mTORC2 formation. Everolimus effectively targets mTORC2-dependent signaling and ERK1/2 activation, an effect that sirolimus is lacking. ERK1 and ERK2 are serine/threonine kinases that are involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, survival and reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. A functional link between ERK and mTORC2 has been shown. Thus inhibition of ERK by everolimus may occur via mTORC2 [26]. Arrows and bars represent activation and inhibition, respectively. Please note that the mTOR pathway is greatly simplified. For more details and explanation of the acronyms, please see [23]. Abbreviations: EVL: everolimus, SRL: sirolimus.

3. Pharmacokinetics and Drug Metabolism

Although there is some overlap between sirolimus and everolimus pharmacokinetic properties, such as wide tissue distribution, poor correlation between dose and systemic exposure but close correlation between exposure (area under the curve, AUC) and trough concentration, high inter-patient variability, a relatively narrow therapeutic index and the need for dose adjustments guided by therapeutic drug monitoring to ensure that trough blood concentrations fall within the respective target ranges [24,25,27,28], there are also important clinically relevant differences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of sirolimus and everolimus pharmacokinetics.

| Sirolimus | Everolimus | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Pharmacokinetics | ||

|

| ||

| Time to peak concentration (tmax) | 2 hoursa | 1–2 hours |

|

| ||

| Time to steady state | 6 days | 4 days |

|

| ||

| Systemic bioavailability | 10% (rats) 15% (humans) 14% (humans) |

16% (rats)b |

|

| ||

| Elimination half-life, mean (SD) | 62 (16) hours | 28 (7) hours |

|

| ||

| Metabolism | ||

|

| ||

| Excretion | ||

| Feces | 91.1%c | 80%d |

| Urine | 2.2%c | 5%d |

|

| ||

| Effect of simultaneous CsA administration | ||

| AUC | Increased 230%e | Increased 168% |

| Cmax | Increased 116%e | Increased 82% |

|

| ||

| Dosing | ||

|

| ||

| Loading dose | Recommended (three times the maintenance dose) | Not recommended |

|

| ||

| Frequency of maintenance dosing | Once daily | Twice daily |

|

| ||

| Food | Consistently with or without food | Consistently with or without food |

|

| ||

| Timing of CsA | 4 hours after CsA dosing | Simultaneous |

Compiled from data reported by references [27–29, 44–47]. Abbreviations: AUC, area-under-the-concentration-time-curve; Cmax, maximum concentration; CsA, cyclosporine; SD, standard deviation; tmax; time-to-maximum concentration

Based on multiple doses in stable kidney transplant patients

Since there has not been a clinical everolimus IV formulation, absolute bioavailability in humans has not been determined.

Percentage of radioactivity recovered from the feces and urine after administration of a single radiolabelled dose in healthy volunteers

Percentage radioactivity recovered from the feces and urine after administration of a single radiolabelled dose in transplant patients receiving CsA

80% (AUC) and 37% (Cmax) when sirolimus was administered 4 hours after CsA [46]

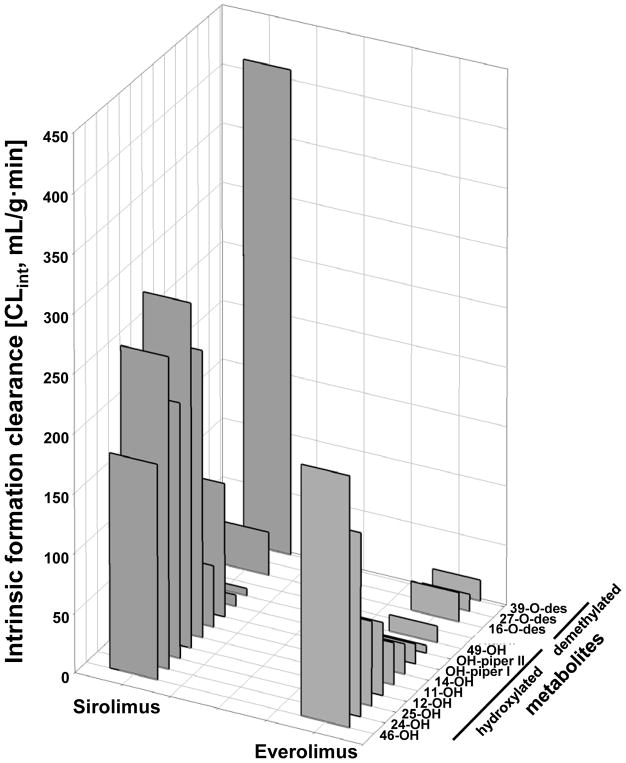

Everolimus is a second generation sirolimus derivative specifically developed to have improved pharmacokinetic properties including, but not limited to, facilitated oral formulation, higher oral bioavailability and better metabolic stability in comparison to sirolimus [13,19]. The everolimus C(40) 2-hydroxyethyl group alters its physicochemical properties and is sterically altering everolimus-protein interactions [13,19]. This may result in hindrance to bind to proteins, a different binding angle and changes in affinity to proteins which may explain the different interactions with FK-binding protein and the mTOR pathway as already aforementioned [13,19,26]. A comparative pharmacokinetic study in rats indicated faster absorption and higher oral bioavailability of everolimus than of sirolimus (16% versus 10%) [29]. This may at least partially be due to the finding that in addition to p-glycoprotein, sirolimus is also removed from intestinal cells by a second efflux system for which everolimus appears not be a substrate [30]. Intestinal efflux transporters in concert with intestinal drug metabolizing enzymes reduce oral bioavailability of everolimus and sirolimus [31,32]. This different substrate patterns for efflux transporters in addition to differences in lipophilicity and affinity to FK-binding proteins may also contribute to the distinct tissue distribution patterns of everolimus and its metabolites in comparison to sirolimus, alone and if combined with cyclosporine [33–37]. Differences between sirolimus and everolimus in terms of protein interactions are also the reason for the different metabolite patterns and the much lower intrinsic formation clearance of everolimus than of sirolimus metabolites by human liver microsomes, which was 2.7-fold lower for everolimus than for sirolimus [38]. Moreover, in this study the hepatic metabolite patterns of everolimus and sirolimus were found to be markedly different [38] (Figure 3). Most notably, the major metabolism reaction in sirolimus, 39-O-demethylation, was approximately 15-fold slower for everolimus [39]. Instead the major drug metabolism reactions of everolimus were hydroxylation in the C(11), C(12), C(14), C(46), C(25) and C(24) positions. This was reflected in the metabolite patterns detected in trough blood concentrations from kidney transplant patients treated with everolimus [40]. The only demethylated metabolite consistently detected in these samples was 16-O-desmethyl everolimus. Using a mechanism-based approach involving quantum chemical, docking, and molecular dynamics calculations suggested that hydrogen donor functionalities close to the metabolic site and in appropriate relative position to it are important for anchoring sirolimus and everolimus at the catalytic heme center of the cytochrome P4503A drug metabolizing enzymes [39]. Due to the C(40) hydroxyethyl group these differ and explain the distinct metabolite patterns and intrinsic clearances by the major drug metabolizing enzymes being responsible for first pass metabolism and systemic elimination of sirolimus and everolimus in patients [39].

Figure 3. Comparison of everolimus and sirolimus in vitro metabolism after incubation with human liver microsomes.

Data is taken from [36]. To facilitate visual comparison error bars are not shown. Abbreviations: -OH: hydroxy everolimus or hydroxy sirolimus, -des: desmethyl everolimus or desmethyl sirolimus, OH-piper: hydroxy piperidine everolimus or hydroxy piperidine sirolimus. The exact hydroxylation positions at the piperidine ring could not be identified, however, different high-performance liquid chromatography retention times suggested hydroxylation at different positions (hydroxy piperidine I and II).

Overall, systemic clearance of everolimus is faster than that of sirolimus, such that the elimination half-life of everolimus is considerably shorter than for sirolimus (mean± standard deviation: 28± 7 versus 62± 16 hours) [27,28]. A shorter terminal half-life means that steady state is reached faster, the response to dose changes is faster and everolimus is faster eliminated from the system than sirolimus if dosing is discontinued. Moreover, everolimus is dosed twice daily versus once daily for sirolimus. Clinically, the longer elimination half-life of sirolimus has led to recommendations that a loading dose of three times the maintenance dose be administrated to achieve steady-state concentrations within one day in most patients [27,28]. In the absence of a loading dose, steady state is not reached until day 6 [27,28]. No loading dose is necessary for everolimus. Key pharmacokinetic parameters of sirolimus and everolimus are compared in Table 1.

Differences in physicochemical properties also appear to affect the influence of food on absorption (Table 2). When everolimus is taken with a high-fat meal, data from healthy volunteers and kidney transplant patients show a decrease or no change in total exposure although the peak concentration is later and lower [41,42]. In contrast, although the peak concentration of sirolimus is also delayed and diminished in the presence of a high-fat meal, systemic exposure is increased compared to fasting healthy subjects [43]. Data on the effect of food on sirolimus absorption in transplant recipients are lacking. Nevertheless, both drugs should be taken consistently with or without food [44,45] to minimize unnecessary fluctuations in systemic exposure.

Table 2.

Comparison of the effects of high-fat meal versus fasting conditions on pharmacokinetic parameters of sirolimus and everolimus.

| Study | Population | mTOR inhibitor | Pharmacokinetic parameter | Effect of high-fat meal versus fasting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zimmerman et al., 1999 [43] | 22 healthy adults | Sirolimus (single dose) | AUC | Increased by 35% |

| Cmax | Decreased by 34% | |||

| C0 | No data | |||

| tmax | Delayed (mean 2.3 hours) | |||

| Kovarik et al., 2002 [41] | 24 healthy male adults | Everolimus (single dose) | AUC | Decreased by 16% |

| Cmax | Decreased by 60% | |||

| C0 | No data | |||

| tmax | Delayed (median 1.25 hours) | |||

| 6 stable adult kidney transplant patients | Everolimus (steady state dosing) | AUC | Decreased by 21% | |

| Cmax | Decreased by 53% | |||

| C0 | No effect | |||

| tmax | Delayed (median 1.75 hours) | |||

| Kovarik et al., 2003 [42] | 24 healthy adults | Everolimus (single dose) | AUC | No effect (ratio fed/fasting 0.99) |

| Cmax | Decreased 50% | |||

| C0 | No data | |||

| tmax | Delayed (median 2.5 hours) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area-under-the-concentration-time-curve; C0, trough blood concentration; Cmax, maximum concentration; tmax, time-to-maximum concentration.

Due to differences in cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism [38,39] and in affinities to active drug transporters [30], it is not unreasonable to assume that there may also be differences between sirolimus and everolimus in terms of drug-drug interactions and food-drug interactions. Several foods and herbs such as grapefruit and St. John’s Wort are known to affect drug metabolism and intestinal absorption of immunosuppressants [31]. However, drug-drug and such food-drug interactions of sirolimus and everolimus have not yet been compared in adequately designed clinical studies.

4. Toxicodynamic Effects on Neuronal Metabolism

Systematic in vitro and in vivo studies directly comparing the toxicodynamic effects of everolimus and sirolimus in combination with CNIs have provided evidence that, while sirolimus enhances CNI toxicity, everolimus is either lacking this negative effect or even has the ability to antagonize CNI toxicity [34,48–51]. Sirolimus enhances the negative effects of cyclosporine on neuronal cell metabolism via two mechanisms:

Sirolimus enhances the distribution of cyclosporine into brain tissue and brain mitochondria [34,52]. This also occurs in the rat kidney [36,37,53].

Cyclosporine inhibits the Krebs cycle and oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria [54,55]. An attempt is made by the cells to compensate for the inhibition of mitochondrial high-energy phosphate production by activating cytosolic anaerobic glycolysis as an alternative source for ATP [34,48,50]. This is indicated by a measurable increase in lactate production. Sirolimus has much less of a direct effect on mitochondrial metabolism than cyclosporine [50,51,54], but it inhibits anaerobic glycolysis [34,48]. While inhibition of anaerobic glycolysis only has a relatively minor negative effect on cell energy metabolism with mitochondrial energy metabolism intact, when combined with cyclosporine, by inhibiting anaerobic glycolysis sirolimus inhibits the main compensatory mechanism thus enhancing the cyclosporine-induced negative effects on energy metabolism [48–50, 52, 53]. mTORC1/AKT stimulates glycolysis, thus eliciting cell survival in many organs [56]. On the other hand inhibition of mTOR reduces glycolytic flux as observed in the aforementioned studies showing the enhancement of the negative effects of CNIs on cell metabolism by sirolimus.

Although both mTOR inhibitors, direct comparison of everolimus and sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine showed that everolimus behaved very differently in these models. At the concentrations tested, in contrast to sirolimus, everolimus antagonized the negative effects of cyclosporine on energy metabolism in the rat brain [34, 48–51].

There is also evidence that everolimus alone, but not sirolimus, stimulates mitochondrial oxidation. In rat brain slices, in contrast to sirolimus which reduced high-energy metabolism, everolimus stimulated high-energy metabolism as indicated by significantly higher phosphocreatine and NAD/NADH concentrations [51]. In addition, this study confirmed that sirolimus enhanced the negative effects of cyclosporine on high-energy metabolism while everolimus antagonized those.

One of the key differences between sirolimus and everolimus in these studies was that at therapeutically relevant concentrations everolimus, but not sirolimus, could distribute into brain mitochondria [34, 50]. Interestingly, at very high concentrations sirolimus could also be found in brain mitochondria and when this was the case, sirolimus also was able to antagonize the negative effects of cyclosporine on mitochondrial metabolism. In addition, at concentrations close to the therapeutic range, sirolimus increased while everolimus decreased cyclosporine concentrations in mitochondria [34].

5. Toxicodynamic Effects on Renal Metabolism and Function

Various studies have evaluated the impact of the mTOR inhibitors on renal cell metabolism and function. The effects of everolimus and sirolimus on human podocyte cultures were compared [57]. While there was some overlap, there were also differences such as a greater reduction in synaptopodin, podocin and nephrin expression, less NFκB activation, and more apoptosis when podocyte cultures were exposed to sirolimus than when exposed to everolimus. Yet these results are based upon cell cultures and it is unclear if these in vitro differences also translate into clinical differences [57].

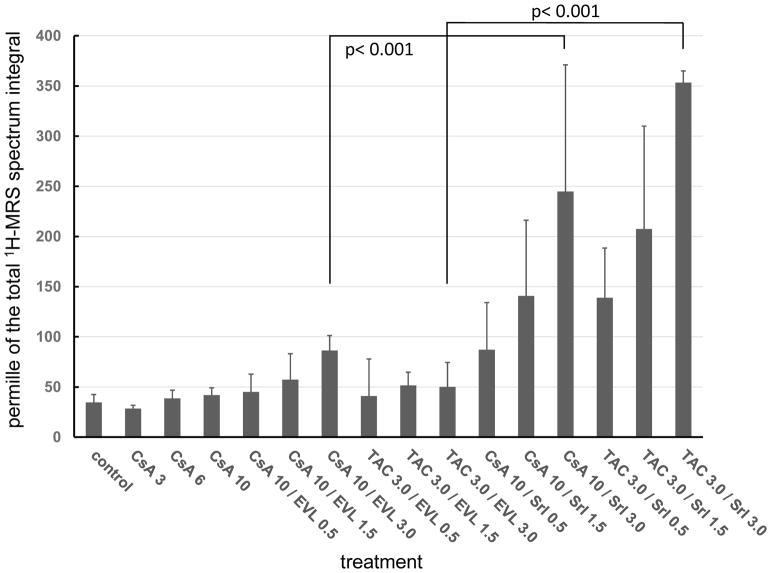

The effects of cyclosporine or tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus on the rat kidney following 28 days of oral administration were systematically compared with those of cyclosporine or tacrolimus in combination with everolimus [36], The study was based on a model previously developed and verified for cyclosporine toxicity [58,59]. The results showed sirolimus to dose-dependently enhance tacrolimus and cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. This was confirmed by histologies, changes in urine metabolite patterns and changes in kidney cell metabolism as assessed using various nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry metabolomics technologies. In contrast, with increasing doses, everolimus in combination with cyclosporine and tacrolimus had less of a negative effect on the kidneys and compared favorably with sirolimus [36] (Figure 4). Similar results were found when in the same model the CNI tacrolimus was combined with sirolimus and everolimus [60] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Comparison of the effects of sirolimus (SRL) and everolimus (EVL) in combination with cyclosporine (CsA, 10 mg/kg/day) on the proximal tubule kidney injury marker trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) in rat urine after 28 days of exposure as assessed using 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS).

Data is taken from references [36,60]. Values were normalized based on the total spectrum integral to compensate for differences in urine concentrations. Thus, all values are per mille of the total integral and are reported as means ± standard deviations (n=4). Data among groups was compared using analysis of variance in combination with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Not all statistically significant differences are shown to facilitate visual comparison of the data. The numbers in the treatment axis labels give the doses in mg/kg/day. All immunosuppressants were administered by oral gavage resulting in whole blood concentrations within the target range of transplant patients [36,60].

The distinct effects of sirolimus and everolimus on the kidney in combination with cyclosporine were further confirmed in rats receiving a salt-depleted diet and the same sirolimus and everolimus doses (0.3 mg/kg/day) for 28 days [61]. Tubular injury, interstitial fibrosis and arteriolopathy were evaluated. Neither sirolimus nor everolimus alone caused detectable histological injury during the observation period. Also, nephrotoxicity was not observed at a daily dose of 5 mg/kg cyclosporine but was evident after treatment with a daily dose of 10 mg/kg cyclosporine. The combination of sirolimus with 5 mg/kg/day cyclosporine resulted in significant enhancement of cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. However, this was not observed when the corresponding doses of everolimus and cyclosporine were co-administered [61]. In another study, salt-depleted rats treated for 28 days, everolimus or sirolimus alone did not result in pancreatic dysfunction and renal injury, however, when combined with cyclosporine, both sirolimus and everolimus enhanced cyclosporine-induced pancreatic and renal injury [37]. It should be noted that the cyclosporine: everolimus dose ratio was much higher than in both previously discussed studies [36,61] and in contrast to the study described in [36], during which the immunosuppressants were administered by oral gavage, immunosuppressants were administered subcutaneously [37].

In summary, the toxicodynamic differences between sirolimus and everolimus alone and in combination with CNI as observed in in vitro and animal studies may be explained by differences in affinity to active drug efflux transporters, in tissue distribution, in distribution into mitochondria, in drug-drug interactions with cyclosporine in terms of distribution into cells and mitochondria, in binding to FKBP, in effects on the mTOR pathway and/or differences in mitochondrial metabolism.

Notwithstanding these in vitro and animal results, early clinical trials had suggested that everolimus, just like sirolimus, enhances cyclosporine nephrotoxicity [62,63]. In said clinical trials, trough blood concentration ratios ranged from 1: 10 to 1: 100 (everolimus: cyclosporine) [64], while concentration ratios in the aforementioned in vitro and animal studies were 1:3.3 to 1:5 [34,36,48–51]. When in such in vitro studies everolimus was tested combined with cyclosporine concentrations exceeding this ratio, everolimus-induced inhibition of glycolysis became critical and everolimus behaved just like sirolimus [50]. This may explain why in the first phase III clinical trials with everolimus no difference to sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine was observed [62–64].

In this context, it is interesting to note that using an exposure-effect modeling approach based on the data from a twelve-month phase III clinical trial in heart transplant recipients [65], Starling et al. [66] found that the negative effects on creatinine serum concentrations were associated with cyclosporine trough blood concentrations, while everolimus average trough blood concentrations were not related to kidney dysfunction and did not enhance cyclosporine nephrotoxicity within the observed exposure range. In fact, the data may even suggest that higher everolimus exposure antagonizes the negative effects of cyclosporine on kidney function. This seems consistent with the aforementioned in vitro and animal studies but will require further confirmation.

6. Effects of Sirolimus and Everolimus on the Vascular Endothelium

Functionality of the vascular endothelium plays a critical role for the outcome after organ transplantation. Endothelial responses mediated by the immune system and inflammatory reactions as well as those caused by immunosuppressant toxicity contribute to transplant allograft vasculopathy, hypertension and the increased cardio-vascular risk after transplantation. In these regards, mTOR inhibitors are a promising class of immunosuppressants as these have been shown not to possess the negative effects associated with CNI treatment and even can prevent endothelial vasculopathy [67]. There is evidence that the effects of sirolimus and everolimus on the vascular endothelium differ. As aforementioned, in human endothelial aorta cells everolimus was shown to be a more potent mTORC2 inhibitor than sirolimus and in contrast to sirolimus, everolimus inhibited ERK phosphorylation [26].

To compare the effects of immunosuppressants on vascular function, rats were treated for 10 days [68]. Hereafter, aortic vascular endothelial and smooth muscle function was assessed ex vivo in organ baths. Aortic contractions in response to noradrenaline were significantly greater in sirolimus than in everolimus-treated rats. Moreover, endothelial-dependent maximum relaxation in response to acetylcholine exposure after everolimus treatment was not different from the controls whereas it was markedly reduced in sirolimus-treated rats. Based on these results, it was concluded that in contrast to sirolimus, everolimus did not negatively affect aortic endothelial and smooth muscle function [68].

In an in vitro study to compare the effects of immunosuppressants alone and of their combinations on the inflammatory response of neutrophils isolated from healthy individuals, Vitiello et al. [69] found that everolimus alone was more effective than sirolimus alone in reducing IL-8 and VEGF release. Importantly, everolimus was the only immunosuppressant tested that was able to increase the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-1RA. These effects were maintained when everolimus was combined with cyclosporine, tacrolimus or mycophenolic acid. Under the same conditions, sirolimus was not as effective as everolimus when combined with other immunosuppressants. The authors concluded that among the tested immunosuppressants everolimus should be most beneficial in preventing coronary allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients [69].

7. Comparison of Sirolimus and Everolimus in Clinical Trials

Clinical trials directly comparing sirolimus and everolimus are lacking. At present only an indirect comparison is possible.

7.1. Immunosuppressive Efficacy

Analyses comparing the incidence of allograft rejection with sirolimus versus everolimus are restricted to one non-randomized, single-center study in de novo kidney transplant patients [70], retrospective single-center analyses in maintenance kidney [71] or heart [72,73] transplant patients converted from CNI immunosuppression to sirolimus or everolimus therapy and one retrospective analysis of maintenance kidney transplant patients switched from sirolimus to everolimus due to a center-wide decision [74]. None of these studies has suggested any clinically relevant or statistically significant difference in the rate of rejection between the two mTOR inhibitors other than a small retrospective analysis by Tenderich et al, in which 4/28 heart patients converted from a CNI to sirolimus experienced rejection versus 0/27 patients converted to everolimus [72]. No patient experienced acute rejection or graft loss during the six month follow-up when patients (n=51) were switched from sirolimus to everolimus [74].

7.2. Renal Function

Kamar et al. [70] undertook a non-randomized, single-center study of 30 de novo kidney transplant patients receiving either sirolimus or everolimus with cyclosporine or steroids with the objective of examining measured glomerular filtration rates (GFR) and tubular function at three months post transplant. At month 3, cyclosporine trough blood concentrations were 128± 10 ng/mL (mean ± standard deviation) in the patients receiving sirolimus and 148± 9 ng/mL in those given everolimus. Mean sirolimus trough blood concentrations were 12.0± 1.6 ng/mL; everolimus trough blood concentrations were 4.2± 0.4 ng/mL. Average GFR was significantly lower in sirolimus-treated patients versus everolimus-treated patients (49± 4 versus 64±4 mL/min/1.73m2, p<0.05), a difference that the authors ascribed to better protection of certain tubular functions (phosphorus reabsorption and uric acid excretion) under everolimus than sirolimus (Table 3). It is interesting to note that GFR was higher in the everolimus cohort despite numerically higher cyclosporine exposure, but on the other hand, sirolimus exposure was higher than the trough blood concentrations targeted today. Smaller retrospective analyses did not find any notable differences in renal function between the two mTOR inhibitors [73,74].

Table 3.

Renal parameters at month 3 post-transplant in de novo kidney transplant patients receiving sirolimus or everolimus with concomitant cyclosporine and steroids [70].

Parameters showing a significant difference between the two mTOR inhibitors are shown. Values are presented as mean (standard deviation)

| Normal range | Sirolimus | Everolimus | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFR (mL/min/1/73m2)a | - | 49 (4) | 64 (4) | <0.05 |

| Free water clearance (mL/min/1.73m2) | - | −0.1 (0.3) | 1.4 (0.5) | <0.01 |

| Serum phosphorus (mmol/L) | 0.8 (1.3) | 0.68 (0.05) | 0.82 (0.03) | <0.05 |

| TmPO4/GFR ratio (mmol/L)b | 0.98 (1.3) | 0.47 (0.04) | 0.66 (0.05) | <0.01 |

| Uric acid clearance (mL/min/1.73m2) | 7 (12) | 4.5 (0.5) | 7.3 (1.3) | <0.05 |

| Urinary pH | - | 6.2 (0.1) | 6.8 (0.1) | <0.01 |

| Urinary acid excretion (mEq/h) | 2.5 – 3.6 | 2.9 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.9) | <0.05 |

Measured by inulin clearance

Renal phosphate threshold

7.3. Discontinuation due to Adverse Events

Retrospective reports offer a mixed picture regarding the relative rates of discontinuation with everolimus and sirolimus [71,73]. In a prospective, non-randomized single-center analysis 56 maintenance heart transplant patients were converted from a CNI-based regimen to either sirolimus or everolimus. mTOR treatment was discontinued in significantly more sirolimus than everolimus patients (p < 0.0001) [75]. Moreover, everolimus showed significantly better survival without edema or infections and only sirolimus treatment was shown to be an independent predictor of adverse events [75]. However, in a larger retrospective study of 409 maintenance kidney transplant patients converted to mTOR inhibition, a numerically higher rate of discontinuation with everolimus (31.4%) versus sirolimus (22.8%, p=0.051) was observed [76]. It should be noted that in these studies there were too many uncontrolled variables to allow for a firm conclusion including, but not limited to, the concomitant immunosuppression regimen, the year of transplantation and immunosuppressant exposure levels.

7.4. Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia, already a common complication after kidney transplantation [77–80], is exacerbated by mTOR inhibitor therapy and use of lipid-lowering therapy is increased two-fold in mTOR inhibitor-treated kidney transplant patients [78]. Table 4 summarizes the limited data available from comparative analyses of the two agents. The most detailed data are reported in a retrospective, single-center analysis of maintenance heart transplant patients in whom sirolimus (n=28) or everolimus (n=27) were introduced in response to development of renal insufficiency, with a concomitant reduction in CNI exposure [72]. Follow-up at 6 and 12 months showed an increase in total cholesterol and triglycerides only in sirolimus-treated patients, despite an accompanying increase in statin use for the sirolimus cohort from 48% at time of conversion to 93% at 12 months. HDL-cholesterol increased only in the everolimus cohort (Table 4). Similar findings were described in [73] following introduction of sirolimus or everolimus in maintenance heart transplant recipients. In contrast, in a non-randomized comparison of de novo kidney transplant patients receiving sirolimus (n=18) or everolimus (n=12), no statistically significant differences in lipid profiles at month 6 post-transplant were found, but there was a tendency to higher levels of total cholesterol and triglycerides in the everolimus group [70]. Carvalho et al. [74] observed no significant change in lipid profiles after conversion of 51 maintenance kidney transplant patients from sirolimus to everolimus. Systematic reviews are also not consistent in their analysis of clinical trials. While in reference [78] no difference was found, reference [79] reports an advantage for everolimus. It has to be noted that in [78] clinical trials were analyzed which used early dosing strategies combining mTOR inhibitors without concomitant CNI reduction while [79] is more recent and is based upon more modern CNI-reduced immunosuppressive regimens.

Table 4. Lipid profiles in comparative analyses of sirolimus and everolimus.

Lipid values are shown as mean (standard deviation) in mmol/L at follow-up. All differences were statistically non-significant unless stated otherwise.

| Study | Design | Patients | Concom -itant IS |

Follow- up |

Statin therapy at baseline (%) |

Total cholesterol | LDL-cholesterol | HDL-cholesterol | Triglycerides | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRL | EVL | SRL | EVL | SRL | EVL | SRL | EVL | SRL | EVL | |||||

| Kamar 2005 [70] | Prospective, Non-randomized Single center | 30 de novo kidney transplant patients | CsA Steroids | 3 months | 22 | 17 | 6.0 (0.4) | 7.2 (0.5) | - | - | - | - | 2.4 (0.4) | 2.8 (0.5) |

| Tenderich 2007 [72] | Retrospective, Single center | 55 maintenance heart transplant patientsc, d | Tac | 12 months | 48a | 44a | 25% increaseb | No change | No change | No change | No change | 15% increase | 65% increaseb | No change |

| Baur 2011 [73] | Retrospective, Single center | 61 maintenance heart transplant patientsc, d | CsA or Tac MPA or Aza Steroids | 6 months | 38 | 27 | Sig. increase (p<0.01) | No sig. change | No data | No data | No sig. change | Sig increase (p<0.02) | Sig. increase (p<0.001) | No sig. change |

Abbreviations: Aza, azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine; EVL: everolimus; IS, immunosuppression; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolic acid; n.s., not significant; sig., significant; SRL: sirolimus; Tac, tacrolimus.

Statin use increased from 48% at time of conversion to SRL to 93% at month 12 (p<0.025) but remained stable in the everolimus group (44% at time of conversion to 59% at month 12, not significant)

Month 6 (data on change to month 12 not provided)

Sirolimus or everolimus introduced after an initial CNI-based regimen in response to a clinical indication, with concomitant reduction in CNI exposure

Absolute values not provided

7.5. Hematology

mTOR inhibition blocks signal transduction of the cytokines that modulate the maturation and proliferation of bone marrow cells [80]. Moreover, availability of iron in concert with mTORC1 activation are involved in the regulation of reticulocytes [81]. In their prospective trial of de novo kidney transplant patients, Kamar et al. [70] observed a higher mean hemoglobin level in everolimus-treated patients three months after transplantation. In heart transplant recipients a transient decrease in hemoglobin levels was observed after initiation of sirolimus that was not observed with everolimus [72,73]. In contrast, conversion of 51 maintenance kidney transplant patients from sirolimus to everolimus was not associated with any change in hematocrit values in a retrospective analysis at a single center [74]. The scant data available on leukocyte and platelet counts does not appear to indicate any consistent difference in the effect of the two mTOR inhibitors.

7.6. Edema

Peripheral edema is a recognized side effect of mTOR inhibitor therapy [80]. Only two analyses, both in maintenance heart transplant patients at single centers (35,37), have compared the incidence of edema in patients receiving sirolimus or everolimus. In a prospective study, Moro et al. [75] observed a lower rate of edema with everolimus (14.3% versus 64.3% with sirolimus, p< 0.001). In their retrospective analysis Baur et al. [73] found edema to be the leading cause of drug discontinuation for 3.1% of everolimus patients versus 28.2% of sirolimus patients (p< 0.01), although information on the frequency of edema elicited by patient questionnaires in their study showed no difference between the two drugs [73].

7.7. Infections

It is generally accepted that immunosuppression increases the risk of infections. Nevertheless, mTOR inhibitors have recently generated interest due to their ability to reduce the risk of viral infections such as those by cytomegalovirus [82,83]. Potential mechanisms include inhibition of the mTOR-dependent viral protein synthesis in host cells and immune-stimulatory effects on memory CD8(+) T-cell differentiation [84,85].

As of today there is no consistent pattern based on the few clinical studies comparing sirolimus and everolimus [70,71,74,75]. One prospective study reported a lower rate of infections with everolimus [75] but no difference was seen in other analyses [70,74]. Sánchez-Fructuoso et al. [71] observed no significant difference in the rate of drug discontinuation due to severe infection between everolimus- or sirolimus-treated patients in their retrospective study of 409 maintenance kidney transplant patients (everolimus 2.3%, sirolimus 4.8%, p=0.17).

7.8. Wound healing

A further safety concern in patients receiving an mTOR inhibitor is the potential interference with normal wound healing processes via their anti-proliferative effects [79,80]. All but one [70] of the analyses that present information on adverse events in patients receiving sirolimus or everolimus was undertaken in maintenance patients [71–73,75], such that information on healing of the transplant incision is virtually absent. Two reviews summarized the results of controlled studies with either sirolimus or everolimus in kidney [86] and heart [87], based on which it appears that the rate of surgical wound healing complications is lower with everolimus. In none of the phase III trials with everolimus in de novo renal transplantation an increase in wound healing complications was observed [88–90]. This is supported by a single center experience [91]. One explanation is the higher sirolimus exposure and loading doses in earlier studies targeting trough whole blood concentrations of 15–20 ng/mL, while everolimus dosing was based on phase II efficacy and safety trials suggesting a trough blood concentration range between 3–8 ng/mL in combination with cyclosporine.

7.9. Endocrine Adverse Effects

mTOR inhibitors seem to delay improvement of gonadal function after transplantation [79]. In sirolimus-treated adolescents a dose-dependent decrease in testosterone levels and an increase in luteinizing hormone were observed [92–94]. No change in sex hormone levels occurred in more recent trials of everolimus in children which used lower immunosuppressant doses [94]. There is some evidence that everolimus in combination with low-dose CNIs does not have a negative effect on growth in pediatric transplant patients [95,96]. In terms of sirolimus, albeit in combination with standard-exposure CNIs, case and case-control studies have reported mixed results of either negative or no effects [94]. Nevertheless, no conclusions can be drawn as early steroid-withdrawal and low CNI exposure also positively affect growth and without a direct comparison in a prospective clinical trial it is impossible to judge if there is a difference between both mTOR inhibitors on growth or not. For a more detailed discussion, please see reference [94].

7.10. Stomatitis

Stomatitis is a dose-limiting effect of mTOR-inhibitors that is believed to be due to a direct toxic effect [79,97]. A recent review comparing transplant studies with everolimus (everolimus (0.75 or 1.0 mg twice daily with reduced or standard-dose tacrolimus or cyclosporine) and sirolimus (sirolimus 2 or 5 mg with cyclosporine ± corticosteroids) [79] reported incidences of stomatitis including unconfirmed oral herpes simplex infections of 2–8% in everolimus and 10–19% in sirolimus studies. Nevertheless, such an indirect comparison is complicated by differences in the CNI regimens. Moreover, a retrospective study comparing everolimus and sirolimus did not observe any statistically significant differences in mouth ulcers [71].

7.11. Conversion from Sirolimus to Everolimus

As aforementioned, switching from sirolimus to everolimus did not result in any rejection episodes during the 6-month observation period [74]. The patients were on a CNI-free drug regimen and doses were converted 1:1. However, this may not be adequate in cyclosporine-treated kidney transplant patients [98]. Given the complex and distinct nature of drug interactions between sirolimus and everolimus with cyclosporine and tacrolimus [99] post-conversion dose adjustments guided by therapeutic drug monitoring may be advisable.

A small number of case reports described the clinical effect of conversion from sirolimus to everolimus in response to sirolimus-induced complications. No conversions from everolimus to sirolimus have been reported. Said case reports included sirolimus-induced proteinuria in a liver transplant recipient that improved after switch to everolimus [100] and disappearance of aphthous ulcers under sirolimus [101]. In single kidney [102] and liver [103] transplant patients, sirolimus-induced pneumonitis resolved after switch to everolimus. Nevertheless, an indirect retrospective comparison of kidney transplant patients taking either sirolimus or everolimus at a single center suggested that sirolimus did not cause more cases of pneumonitis than everolimus [104].

8. Expert Opinion

During the pre-clinical and clinical development of sirolimus its propensity to enhance CNI nephrotoxicity was not discovered before late in its clinical development. At this time the underlying toxicodynamic mechanisms were unknown and the risk/benefit ratio of sirolimus/CNI combinations has been a matter of debate ever since. Moreover, first evidence has emerged suggesting that sirolimus and mycophenolic acid, a frequently used combination in CNI-free long term immunosuppressive maintenance protocols, may also be nephrotoxic when co-administered [105]. Although combination immunosuppressive therapy has always been considered the standard after transplantation, drug agencies did not require systematic assessment of potential pharmacodynamics and toxicodynamic interactions in pre-clinical and early clinical studies. Meanwhile, over the last 20 years, research studies have been published that are starting to fill this important knowledge gap. As discussed above, sirolimus seems to enhance cyclosporine toxicity by increasing its distribution into toxicologically relevant organ tissues and mitochondria and it inhibits anaerobic glycolysis, which compensates for the negative effects of cyclosporine on mitochondrial energy metabolism [50,52]. This was discovered even before the exact mechanisms involved in the regulation of glycolysis via the mTOR pathway were known [34,48,56]. Based on their structural relationship, their common pharmacodynamic target, the mTOR pathway, and similar efficacy and safety profiles in the early phase III clinical trials combining full-dose cyclosporine with everolimus, it has originally been assumed that sirolimus and everolimus are clinically similar immunosuppressants. However, as shown by in vitro and animal studies sirolimus and everolimus have substantially different pharmacodynamic and toxicodynamic properties, notably their distinct effects on the mTOR pathway, mitochondrial energy metabolism, vascular endothelial function and inflammatory response. Based on present published evidence, it seems reasonable to assume that the everolimus C(40) hydroxyethyl group which sterically modifies everolimus-protein interactions, as for example shown in the case of cytochrome P4503A [39], plays an important role in the mechanistic differences between these two mTOR inhibitors. The next important question is if these differences translate into a clinical advantage. As discussed above, there is clinical evidence that this may be true, but at present objective, reliable clinical comparison of sirolimus and everolimus is complicated due to the lack of well-controlled, prospective studies that directly compare sirolimus and everolimus and the fact that most sirolimus studies are earlier studies, with trials based on either standard-exposure CNI or CNI-free immunosuppressive drug regimens, while the in most cases more recent everolimus studies are assessing everolimus in combination with low-exposure CNI. Moreover, everolimus is currently simply the better studied drug. Most of the sirolimus are older than the everolimus studies and it is reasonable to expect that these latter studies avoided the known problems as observed in previous sirolimus studies. Nevertheless, corresponding sirolimus studies are lacking so that it is unknown if sirolimus in studies with a similar design would match everolimus’ performance or not.

Although nowadays, at least in the United States and Europe, tacrolimus is the most frequently used CNI, there is far less data about toxicodynamic interactions between tacrolimus and everolimus or sirolimus than for cyclosporine. In vitro and animal studies infer that the cyclosporine/everolimus exposure ratio is critical. It can be hypothesized that if the systemic exposure (trough blood levels are a surrogate marker for systemic exposure) ratio is <5:1 everolimus has the potential to antagonize cyclosporine toxicity, if it is higher, everolimus will not enhance but will also not antagonize cyclosporine toxicity and if it is too high, as in some phase III clinical trials [63,64], everolimus will enhance cyclosporine toxicity. Based hereon, it can be speculated that everolimus should be especially useful in long-term immunosuppressive maintenance protocols in combination with low-dose CNI. Indeed, an increasing number of clinical studies have successfully used full-dose everolimus resulting in trough blood concentrations between 3–8 ng/mL in combination with low dose CNIs [106]. Those studies also suggest that everolimus does not enhance CNI toxicity as long as CNIs are not dosed too high relative to everolimus.

To further assess the potential of mTOR inhibitors in combination with low-dose CNI in immunosuppressive long-term maintenance protocols, the following will be required:

Additional mechanistic studies to better understand the differences between sirolimus and everolimus in terms of their distinct effects on the mTOR pathway, mitochondrial energy metabolism and vascular endothelial function and to develop strategies how to translate such mechanistic differences into a clinical advantage.

Systematic, prospective dose finding studies to assess which CNI/mTOR inhibitor ratio will be best to avoid kidney injury and preserve vascular endothelial function while maintaining immunosuppressive efficacy.

Prospective clinical trials directly comparing sirolimus and everolimus in combination with low-dose CNI to assess if the aforementioned pharmacodynamic and toxicodynamic differences will translate into a clinical advantage of everolimus.

Highlights.

Everolimus has different clinical pharmacokinetics than sirolimus, most importantly a shorter elimination half-life.

Everolimus is metabolized differently than sirolimus and has different affinities to active efflux drug transporters.

Everolimus affects the mTOR pathway differently than sirolimus and has a higher potency in terms of interacting with mTOR complex 2.

Everolimus distributes differently into tissues and sub-cellular components.

Everolimus has the potential to antagonize calcineurin inhibitor neuro- and nephrotoxicity at clinically relevant concentrations.

Head-to-head prospective clinical trials to directly compare sirolimus and everolimus are lacking.

Acknowledgments

Grant support

This work was supported by the United States National Institutes of Health, grant R01HD070511 (UC).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

BN has received research funding and honoraria from Novartis Pharma and has served on Novartis Pharma advisory committees. JK and UC have received research funding from Novartis Pharma. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents, received or pending, or royalties.

References

- 1.Peddi VR, Wiseman A, Chavin K, et al. Review of combination therapy with mTOR inhibitors and tacrolimus minimization after transplantation. Transplant Rev. 2013;27(4):97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yost SE, Byrne R, Kaplan B. Transplantation: mTOR inhibition in kidney transplant recipients. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7(10):553–5. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manito N, Delgado JF, Crespo-Leiro MG, et al. Clinical recommendations for the use of everolimus in heart transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando) 2010;24(3):129–42. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asrani SK, Leise MD, West CP, et al. Use of sirolimus in liver transplant recipients with renal insufficiency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2010;52(4):1360–70. doi: 10.1002/hep.23835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Simone P, Metselaar HJ, Fischer L, et al. Conversion from a calcineurin inhibitor to everolimus therapy in maintenance liver transplant recipients: a prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Liver Transplant. 2009;15(10):1262–9. doi: 10.1002/lt.21827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asrani SK, Wiesner RH, Trotter JF, Klintmalm G, Katz E, Maller E, Roberts J, Kneteman N, Teperman L, Fung JJ, Millis JM. De novo sirolimus and reduced-dose tacrolimus versus standard-dose tacrolimus after liver transplantation: the 2000–2003 phase II prospective randomized trial. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(2):356–66. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilar E, Perez-Garcia J, Tabernero J. Pushing the envelope in the mTOR pathway: the second generation of inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(3):395–403. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin D, Colombi M, Moroni C, et al. Rapamycin passes the torch: a new generation of mTOR inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(11):868–80. doi: 10.1038/nrd3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giordano A, Romano A. Inhibition of human in-stent restenosis: a molecular view. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2011;11(4):372–7. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park KW, Kang SH, Velders MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of everolimus- versus sirolimus-eluting stents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials. Am Heart J. 2013;165(2):241–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neumayer H-H. Introducing everolimus (Certican) in organ transplantation: an overview of preclinical and early clinical developments. Transplantation. 2005;79(9 Suppl):S72–S75. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000162436.17526.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sehgal SN, Molnar-Kimber K, Ocain TD, et al. Rapamycin: a novel immunosuppressive macrolide. Med Res Rev. 1994;14(1):1–22. doi: 10.1002/med.2610140102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sedrani R, Cottens S, Kallen J, Schuler W. Chemical modification of rapamycin: the discovery of SDZ RAD. Transplant Proc. 1998;30(5):2192–4. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Favre HA, Powell WH. IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Name. Cambridge, UK: The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2013. Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 15•.Schreiber SL. Chemistry and biology of the immunophilins and their immunosuppressive ligands. Science. 1991;251(4991):283–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1702904. Inroduces the concept of a sirolimus FKBP-binding and an mTOR-binding domain. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Womer KL, Kaplan B. Recent Developments in kidney transplantation– a critical assessment. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(6):1265–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahan BD, Gibbons S, Tejpal N, et al. Synergistic interactions of cyclosporine and rapamycin to inhibit immune performances of normal human peripheral blood lymphocytes in vitro. Transplantation. 1991;51(1):232–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199101000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schuurman HJ, Cottens S, Fuchs S. SDZ-RAD, a new rapamycin derivative: synergism with cyclosporine. Transplantation. 1997;64(1):32–35. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuler W, Sedrani R, Cottens S, et al. SDZ RAD, a new rapamycin derivative: pharmacological properties in vitro and in vivo. Transplantation. 1997;64(1):36–42. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, et al. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth dependent activation and signal transduction by the 70 kD S6 protein kinases. Cell. 1992;69(7):1227–36. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90643-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dumont FJ, Su Q. Mechanism of action of the immunosuppressant rapamycin. Life Sci. 1996;58(5):373–95. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02233-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17(6):596–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149(2):274–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mabasa VH, Ensom MH. The role of therapeutic monitoring of everolimus in solid organ transplantation. Ther Drug Monit. 2005;27(5):666–76. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000175911.70172.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenton SB, Partovi N, Ensom MH. Sirolimus: the evidence for clinical pharmacokinetic monitoring. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(8):769–86. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Jin YP, Valenzuela NM, Ziegler ME, et al. Everolimus inhibits anti-HLA I antibody-mediated endothelial cell signaling, migration and proliferation more potently than sirolimus. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(4):806–19. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12669. Provides evidence that sirolimus and everolimus have distinct effects on the mTOR pathways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahalati K, Kahan BD. Clinical pharmacokinetics of sirolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2001;40(8):573–85. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200140080-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirchner GI, Meier-Wiedenbach I, Manns MP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of everolimus. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(2):83–95. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowe A, Bruelisauer A, Duerr L, Guntz P, Lemaire M. Absorption and intestinal metabolism of SDZ-RAD and rapamycin in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27(5):627–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30•.Crowe A, Lemaire M. In vitro and in situ absorption of SDZ-RAD using a human intestinal cell line (Caco-2) and a single pass perfusion model in rats: comparison with rapamycin. Pharm Res. 1998;15(11):1666–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1011940108365. Shows that sirolimus and everolimus have different affinity patterns in terms of active efflux drug transporters, which may at least in part explain their difference in terms of pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and drug-drug interactions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christians U, Schmitz V, Haschke M. Functional interactions between p-glycoprotein and CYP3A in drug metabolism. Exp Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005;1(4):641–654. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christians U, Strom T, Zhang YL, et al. Active drug transport of immunosuppressants: new insights for pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000183385.27394.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serkova N, Hausen B, Berry GJ, et al. Tissue distribution and clinical monitoring of the novel macrolide immunosuppressant SDZ-RAD and its metabolites in monkey lung transplant recipients: interaction with cyclosporine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294(1):323–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34••.Serkova N, Jacobsen W, Niemann CU, Litt L, et al. Sirolimus, but not the structurally related SDZ-RAD (everolimus), enhances the negative effects of cyclosporine on mitochondrial metabolism in the rat brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;133(3):875–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704142. Showed for the first time that mTOR inhibition also inhibts anaerobic glycolysis and that this is one of the machanisms that enhances the negative effects of cyclosporine on cell metabolism. The study also showed that at clinically relevant concentrations everolimus, but not sirolimus, can distribute into mitochondria. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gottschalk S, Cummins CL, Leibfritz D, et al. Age and sex differences in the effects of the immunosuppressants cyclosporine, sirolimus and everolimus on rat brain metabolism. Neurotoxicol. 2011;32(1):50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bohra R, Schöning W, Klawitter J, et al. Everolimus and sirolimus in combination with cyclosporine have different effects on renal metabolism in the rat. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Piao SG, Bae SK, Lim SW, et al. Drug interaction between cyclosporine and mTOR inhibitors in experimental model of chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity and pancreatic islet dysfunction. Transplantation. 2012;93(4):383–9. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182421604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobsen W, Serkova N, Hausen B, et al. Comparison of the in vitro metabolism of the immunosuppressants sirolimus and RAD. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1–2):514–5. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(00)02116-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39•.Kuhn B, Jacobsen W, Christians U, et al. Metabolism of sirolimus and its derivative everolimus by cytochrome P450 3A4: Insights from docking, molecular dynamics, and quantum chemical calculations. J Med Chem. 2001;44(12):2027–34. doi: 10.1021/jm010079y. Molecular dynamics computer simulations and docking analyses show that the C(40) hydroxyethyl moïety markedly changes everolimus-protein interactions in comparison with sirolimus. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strom T, Haschke M, Bendrick-Peart J, et al. Everolimus metabolite patterns in the blood of kidney transplant patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2007;29(5):592–9. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181570830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kovarik JM, Hartmann S, Figueiredo J, et al. Effect of food on everolimus absorption: quantification in healthy subjects and a confirmatory screening in patients with renal transplants. Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22(2):154–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.3.154.33542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovarik JM, Noe A, Berthier S, et al. Clinical development of an everolimus pediatric formulation: relative bioavailability, food effect, and steady-state pharmacokinetics. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43(2):141–7. doi: 10.1177/0091270002239822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmerman JJ, Ferron GM, Lim HK, Parker V. The effect of a high-fat meal on the oral bioavailability of the immunosuppressant sirolimus (rapamycin) J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(11):1155–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapamune. Summary of Product Characteristics. Pfizer, Sandwich; United Kingdom: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Certican. Basic Prescribing Information. Novartis Pharma AG; Basel, Switzerland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmerman JJ, Harper D, Getsy J, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetic interactions between sirolimus and microemulsion cyclosporine when orally administered jointly and 4 hours apart in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43(10):1168–76. doi: 10.1177/0091270003257227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kovarik JM, Kalbag J, Figueiredo J, et al. Differential influence of two cyclosporine formulations on everolimus pharmacokinetics: a clinically relevant pharmacokinetic interaction. J Clin Pharmcol. 2002;42(1):95–9. doi: 10.1177/0091270002042001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christians U, Gottschalk S, Miljus J, et al. Alterations in glucose metabolism by cyclosporine in rat brain slices link to oxidative stress: interactions with mTOR inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143(3):388–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49•.Serkova N, Litt L, Leibfritz D, et al. The novel immunosuppressant SDZ-RAD protects rat brain slices from cyclosporine-induced reduction of high-energy phosphates. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129(3):485–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703079. Using a metabolomics approach, this is the first study to show substantial toxicodynamic differences of sirolimus and everolimus on cell energy metabolism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serkova N, Christians U. Transplantation: Toxicokinetics and mechanisms of toxicity of cyclosporine and macrolides. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2003;4(11):1287–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51•.Klawitter J, Gottschalk S, Hainz C, Leibfritz D, Christians U, Serkova NJ. Immunosuppressant neurotoxicity in rat brain models: oxidative stress and cellular metabolism. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23(3):608–19. doi: 10.1021/tx900351q. Shows that everolimus alone has the potential to stimulate mitochondrial energy metabolism, while sirolimus has negative effects. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serkova NJ, Christians U, Benet LZ. Biochemical mechanisms of cyclosporine neurotoxicity. Mol Interv. 2004;4(2):97–107. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.2.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Podder H, Stepkowski SM, Napoli KL, et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions augment toxicities of sirolimus/cyclosporine combinations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12(5):1059–71. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1251059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serkova N, Litt L, James TL, Sadee W, et al. Evaluation of individual and combined neurotoxicity of the immunosuppressants cyclosporine and sirolimus by in vitro multinuclear NMR. J Exp Pharmacol Ther. 1999;289(2):800–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serkova N, Donohoe P, Gottschalk S, et al. Comparison of the effects of cyclosporine on the metabolism of perfused rat brain slices during normoxia and hypoxia. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab. 2002;22(3):342–52. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200203000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts DJ, Miyamoto S. Hexokinase II integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: Akting on mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(2):248–57. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Müller-Krebs S, Weber L, Tsobaneli J, et al. Cellular effects of everolimus and sirolimus on podocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klawitter J, Bendrick-Peart J, Rudolph B, et al. Urine metabolites reflect time-dependent effects of cyclosporine and sirolimus on rat kidney function. Chem Res Toxicol. 2009;22(1):118–128. doi: 10.1021/tx800253x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Klawitter J, Klawitter J, Kushner E, et al. Association of immunosuppressant-induced protein changes in the rat kidney with changes in urine metabolite patterns: A proteo-metabonomic study. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(2):865–75. doi: 10.1021/pr900761m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christians U, Bohra R, Schoening W, et al. Sirolimus, but not everolimus, enhances tacrolimus nephrotoxicity in the rat. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(Supplement 2):34–35. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shihab FS, Bennett WM, Yi H, et al. Comparitive effects of sirolimus versus everolimus in similar doses and blood trough levels on chronic cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Am J Transplant. 2005;5(Supplement 11):222. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kahan BD for the Rapamune US Study Group. Efficacy of sirolimus compared with azathioprine for reduction of acute renal allograft rejection: a randomize multicenter study. Lancet. 2000;356(9225):194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kahan BD, Kaplan B, Lorber MI, et al. RAD in de novo renal transplantation: comparison of three doses on the incidence and severity of acute rejection. Transplantation. 2001;71(10):1400–6. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200105270-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nashan B. Early clinical experience with a novel rapamycin derivative. Ther Drug Monit. 2002;24(1):53–58. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200202000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eisen HJ, Tuzcu EM, Dorent R, et al. Everolimus for the prevention of allograft rejection and vasculopathy in cardiac-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(9):847–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Starling RC, Hare JM, Hauptman P, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring for everolimus in heart transplant recipients based on exposure-effect modeling. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(12):2126–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Delgado JF, Manito N, Segovia J, et al. The use of proliferation signal inhibitors in the prevention and treatment of allograft vasculopathy in heart transplantation. Transplant Rev. 2009;23(2):69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shing CM, Fassett RG, Brown L, et al. The effects of immunosuppressants on vascular function, systemic oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Transpl Int. 2012;25(3):337–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vitiello D, Neagoe PE, Sirois MG, et al. Effect of everolimus on the immunomodulation of the human neutrophil inflammatory response and activation. Cell Mol Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/cmi.2014.24. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kamar N, Allard J, Ribes D, et al. Assessment of glomerular and tubular functions in renal transplant patients receiving cyclosporine A in combination with either sirolimus or everolimus. Clin Nephol. 2005;63(2):80–6. doi: 10.5414/cnp63080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sánchez-Fructuoso AI, Ruiz JC, Pérez-Flores I, et al. Comparative analysis of adverse events requiring suspension of mTOR inhibitors: everolimus versus sirolimus. Transplant Proc. 2010;42(8):3050–2. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tenderich G, Fuchs U, Zittermann A, et al. Comparison of sirolimus and everolimus in their effects on blood lipid profiles and haematological parameters in heart transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2007;21(4):536–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Baur B, Oroszlan M, Hess O, et al. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus and everolimus in heart transplant patients: a retrospective study. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(5):1853–61. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carvalho C, Coentrão L, Bustorff M, et al. Conversion from sirolimus to everolimus in kidney transplant recipients receiving a calcineurin-free regimen. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(4):E401–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moro JA, Almenar L, Martínez-Dolz L, et al. Tolerance profile of the proliferation signal inhibitors everolimus and sirolimus in heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(9):3034–6. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.González-Costello J, Kaplinsky E, Manito N, et al. High rate of discontinuation of a mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor based regime during long-term follow-up of cardiac transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2012;31(Supplement 4):S224. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hart A, Weir MR, Kasiske BL. Cardiovascular risk assessment in kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.335. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kasiske BL, de Mattos A, Flechner SM, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor dyslipidemia in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(7):1384–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaplan B, Qazi Y, Wellen JR. Strategies for the management of adverse events associated with mTOR inhibitors. Transplant Rev. 2014;28(3):126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buhaescu I, Izzedine H, Covic A. Sirolimus--challenging current perspectives. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(5):577–84. doi: 10.1097/01.ftd.0000245377.93401.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knight ZA, Schmidt SF, Birsoy K, et al. A critical role for mTORC1 in erythropoiesis and anemia. Elife. 2014;3:e01913. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nashan B, Gaston R, Emery V, et al. Review of cytomegalovirus infection findings with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor-based Immunosuppressive therapy in de novo renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2012;93(11):1075–85. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824810e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brennan DC, Aguado JM, Potena L, et al. Effect of maintenance immunosuppressive drugs on virus pathobiology: evidence and potential mechanisms. Rev Med Virol. 2013;23(2):97–125. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andrassy J, Hoffmann VS, Rentsch M, et al. Is cytomegalovirus prophylaxis dispensable in patients receiving an mTOR inhibitor-based immunosuppression? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplantation. 2012;94(12):1208–17. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182708e56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Araki K, Youngblood B, Ahmed R. The role of mTOR in memory CD8 T-cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nashan B, Citterio F. Wound healing complications and the use of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors in kidney transplantation: a critical review of the literature. Transplantation. 2012;94(6):547–61. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3182551021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zuckermann Z, Barten MJ. Surgical wound complications after heart transplantation. Transplant Int. 2011;24(7):627–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Vitko S, Margreiter R, Weimar W, et al. Everolimus (Certican) 12- month safety and efficacy versus mycophenolate mofetil in de novo renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2005;78(10):1532–40. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000141094.34903.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lorber MI, Mulgaonkar S, Butt KM, et al. Everolimus versus myco- phenolate mofetil in the prevention of rejection in de novo renal transplant recipients: a 3-year randomized, multicenter, phase III study. Transplantation. 2005;80(2):244–52. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000164352.65613.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tedesco Silva H, Jr, Cibrik D, Johnston T, et al. Everolimus plus reduced-exposure CsA versus mycophenolic acid plus standard-exposure CsA in renal-transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(6):1401–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koch M, et al. Surgical complications after kidney transplantation: Different impact of immunosuppression, graft function, patient variables and surgical performance. Clin Transplant. 2015 Jan 17; doi: 10.1111/ctr.12513. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Lee S, Coco M, Greenstein SM, et al. The effect of sirolimus on sex hormone levels of male renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2005;19(2):162–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2005.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kaczmarek I, Groetzner J, Adamidis I, et al. Sirolimus impairs gonadal function in heart transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(7):1084–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ganschow R, Pape L, Sturm E, et al. Growing experience with mTOR inhibitors in pediatric solid organ transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17(7):694–706. doi: 10.1111/petr.12147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Billing H, Burmeister G, Plotnicki L, et al. Longitudinal growth on an everolimus-versus an MMF-based steroid-free immunosuppressive regimen in paediatric renal transplant recipients. Transpl Int. 2013;26(9):903–9. doi: 10.1111/tri.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pape L, Ganschow R, Ahlenstiel T. Everolimus in pediatric transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17(5):515–9. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328356b080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mahé E, Morelon E, Lechaton S, et al. Cutaneous adverse events in renal transplant recipients receiving sirolimus-based therapy. Transplantation. 2005;79(4):476–82. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000151630.25127.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rehm B, Keller F, Mayer J, et al. Resolution of sirolimus-induced pneumonitis after conversion to everolimus. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(3):711–3. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kuypers DR. Influence of interactions between immunosuppressive drugs on therapeutic drug monitoring. Ann Transplant. 2008;13(3):11–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neau-Cransac M, Moreau K, Deminière C, et al. Decrease in sirolimus-induced proteinuria after switch to everolimus in a liver transplant recipient with diabetic nephropathy. Transpl Int. 2009;22(5):586–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ram R, Swarnalatha G, Neela P, et al. Sirolimus-induced aphthous ulcers which disappeared with conversion to everolimus. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2008;19(5):819–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Calle L, Tejada C, Lancho C, Mazeucos A. Pneumonitis caused by sirolimus: improvement after switching to everolimus. Nefrologia. 2009;29(5):490–1. doi: 10.3265/Nefrologia.2009.29.5.5240.en.full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.De Simone P, Petruccelli S, Precisi A, et al. Switch to everolimus for sirolimus-induced pneumonitis in a liver transplant recipient – not all proliferation signal inhibitors are the same: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(10):3500–1. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rodríguez-Moreno A, Ridao N, Garcia-Ledesma P, et al. Sirolimus and everolimus induced pneumonitis in adult renal allograft recipients: experience in a center. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(6):2163–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Klawitter J, Klawitter J, Schmitz V, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil enhances the negative effects of sirolimus and tacrolimus on rat kidney cell metabolism. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]