Abstract

Woody perennials adapt their genetic traits to local climate conditions. Day length plays an essential role in the seasonal growth of poplar trees. When photoperiod falls below a given critical day length, poplars undergo growth cessation and bud set. A leaf-localized mechanism of photoperiod measurement triggers the transcriptional modulation of a long distance signaling molecule, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT). This molecule targets meristem function giving rise to these seasonal responses. Studies over the past decade have identified conserved orthologous genes involved in photoperiodic flowering in Arabidopsis that regulate poplar vegetative growth. However, phenological and molecular examination of key photoperiod signaling molecules reveals functional differences between these two plant model systems suggesting alternative components and/or regulatory mechanisms operating during poplar vegetative growth. Here, we review current knowledge and provide new data regarding the molecular components of the photoperiod measuring mechanism that regulates annual growth in poplar focusing on main achievements and new perspectives.

Keywords: poplar, photoperiodic time measurement, seasonal growth, shoot apical growth, circadian clock, flowering locus T, tempranillo, constans

Introduction

Shoot apical growth in poplar is extremely sensitive to day length (Howe et al., 1995). Under long day conditions, internode elongation and shoot organogenesis occur continuously. However, when photoperiod falls below a critical day length (CDL), these events come to a halt and this phenomenon is known as growth cessation (Weiser, 1970; Thomas and Vince-Prue, 1997). Poplar annual growth is therefore controlled by a photoperiodic time measurement (PTM) mechanism. This molecular mechanism is able to recognize seasonal photoperiod information by monitoring regular changes in day or night duration. Thus, the components of PTM must be under the control of light signaling pathways. A pulse of red illumination during the night abolishes short day-induced poplar growth cessation (Howe et al., 1996). Similar night break experiments have been found to accelerate Arabidopsis flowering under conditions of short days (Reed et al., 1994). Such responses to night break experiments suggest that poplar shoot growth and Arabidopsis flowering share a similar photoperiod regulation mechanism. In effect, functional studies have suggested that the genetic control of Arabidopsis flowering time and poplar shoot apical growth is conserved (Böhlenius et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2011; Ding et al., 2018). However, in the present study we show that some features of the PTM mechanism such as the daily expression pattern and molecular function of the FT repressor TEMPRANILLO (TEM) vary between the two plant models. We also describe that by comparing diurnal gene expression with height-associated single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genes, we here identified GIGANTEA (GI) and FLAVIN BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX1 (FKF1), already shown to be involved in poplar seasonal growth (Ding et al., 2018), along with new candidate orthologous genes to Arabidopsis flowering time regulators. Interestingly, the genes VERNALIZATION INDEPENDENCE 4 and 5 (VIP4 and VIP5), AGAMOUS-LIKE (AG-like) and TERMINAL FLOWER 2 (TFL2) associated with the vernalization pathway in Arabidopsis, show robust diurnal rhythms of mRNA accumulation in poplar, suggesting their potential role as photoperiodic regulators of poplar shoot apical growth.

A PTM mechanism controls seasonal development

Photoperiod is the most regular environmental signal that drives seasonal development in many insects, birds, other animals and plants (reviewed in Nelson et al., 2010). The external coincidence hypothesis, initially proposed by Bünning (1936) and later modified by Pittendrigh and Minis (1964), has been the prevailing PTM model tested in many organisms (Goldman, 2001; Pegoraro et al., 2014; Song et al., 2015). This model predicts that seasonal physiological responses are created when, by coincidence, diurnal endogenous rhythms match the external photoperiod. Accordingly, day/night duration is measured through photoperiod-dependent modulation of the activity of an endogenous oscillatory component, which controls seasonal physiologic and developmental responses (Pittendrigh and Minis, 1964). Three basic components are required to create a day length measurement mechanism: (1) a photosensory system which includes photoreceptors, (2) an endogenous oscillator, which has been identified as the circadian clock system, and (3) an endocrine effector or mobile photoperiodic signal that translates photoperiod information from the photosensory system to the target organs. In plants, the molecular nature of these components was firstly identified for Arabidopsis flowering time (Yanovsky and Kay, 2002). In woody perennials, components of the PTM mechanism have been recently identified in poplar (reviewed in Maurya and Bhalerao, 2017). In the sections below, we review the state of the art of this research topic.

Phytochromes as players in the poplar PTM mechanism

It is assumed that the photoperiodic signal is perceived in the leaf through discrimination of light quality information by photoreceptors, which have been linked to growth regulation in poplar (Howe et al., 1996; Olsen et al., 1997; Frewen et al., 2000; Ingvarsson et al., 2008; Ruonala et al., 2008; Kozarewa et al., 2010). In carefully-designed night-break experiments, subjecting plants to red light illumination caused the suppression of short day-induced growth cessation in poplar. This effect was reversed by red light followed by far red light night-break treatment, indicating that phytochromes participate in the photoperiodic regulation of poplar shoot apical growth (Howe et al., 1996). One phytochrome A (PHYA) and two phytochrome B (PHYB) genes, PHYB1 and PHYB2, were identified in poplar (Howe et al., 1998). The overexpression of oat PHYA in hybrid aspen (Populus tremula x tremuloides) showed relative insensitivity to photoperiod-induced growth cessation (Olsen et al., 1997). Conversely, hybrid aspen showing downregulation of PHYA has been noted to cease growth earlier than control plants subjected to photoperiod-inducing conditions below CDL (Kozarewa et al., 2010). Poplar PHYB1 but not PHYB2 has been observed to complement an Arabidopsis phyB mutant indicating that PHYB1 maintains the molecular function of Arabidopsis PHYB, while PHYB2 shows divergent molecular features (Karve et al., 2012). However, quantitative trait loci and single nucleotide polymorphism analyses have genetically linked the timing of photoperiod-induced bud set to PHYB2, but not to PHYB1 (Frewen et al., 2000; Ingvarsson et al., 2008). Thus, PHYA and PHYB2 could play a photosensory function during poplar shoot apical growth and may participate in the PTM mechanism.

Some authors have explored the link between PHYA and the circadian clock. Interestingly, poplar PHYA antisense gave rise to a longer period of leaf movement rhythms than wild type plants indicating that the circadian clock period depends on the PHYA level (Kozarewa et al., 2010).

Poplar circadian clock genes participate in photoperiodic regulation of shoot apical growth

The circadian clock is an endogenous molecular oscillator that creates a 24 h rhythmic pattern of gene expression, physiology, cell division and development (reviewed in Nohales and Kay, 2016). The first clock genes identified in a woody perennial species were chestnut LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY) and TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION 1 (TOC1), orthologs of essential components of the Arabidopsis circadian clock (Ramos et al., 2005). Later, the homologous Arabidopsis genes PSEUDO–RESPONSE REGULATORS (PRR), PRR9, PRR7, and PRR5 were identified in chestnut and these genes showed daily peak expression after LHY in the order PRR9→PRR7→PRR5→TOC1, in a similar serial manner to that seen in Arabidopsis (Ibáñez et al., 2008).

Poplar genes of the circadian clock system have been identified based on sequence homology with their Arabidopsis orthologs (reviewed in Johansson et al., 2015). Poplar has two copies of the LHY transcription factor, denoted LHY1 and LHY2 (Takata et al., 2009). The daily gene expression pattern of poplar LHY1 and LHY2 shows a morning expression peak similar to Arabidopsis and chestnut (Takata et al., 2009; Ibáñez et al., 2010; Ramos-Sánchez et al., 2017). Moreover, the poplar clock has several PRR orthologs of Arabidopsis PRR5, PRR7, PRR9 and PRR1/TOC1, which display a similar daily gene expression pattern to that previously reported in Arabidopsis and chestnut (Ramos et al., 2005; Ibáñez et al., 2008, 2010; Filichkin et al., 2011). Recently, two poplar orthologs of the Arabidopsis clock gene GI, designated GI and GIL, and two F-box protein orthologs of the clock regulator FKF1, denoted FKF1a and FKF1b, have been identified (Ding et al., 2018).

Pioneer functional analyses of poplar LHY and TOC1 clock genes revealed that the downregulation of LHY or TOC1 caused a drastic delay in growth cessation with respect to the wild type, confirming that circadian clock function is needed for seasonal regulation of growth (Ibáñez et al., 2010). Remarkably, both LHY and TOC1 RNA interference (RNAi) plants showed a reduced period relative to their wild type counterparts, the period in LHY RNAi being much shorter than in TOC1 RNAi (Ibáñez et al., 2010). This observation prompts the interesting question of how the PTM mechanism works. Thus, it could be shortening of the internal period or reduced levels of LHY or TOC1 expression or both together that were responsible for the observed late growth cessation phenotype in LHY and TOC1 RNAi plants.

FT2 acts as mediator of photoperiodic signaling to control poplar shoot apical growth

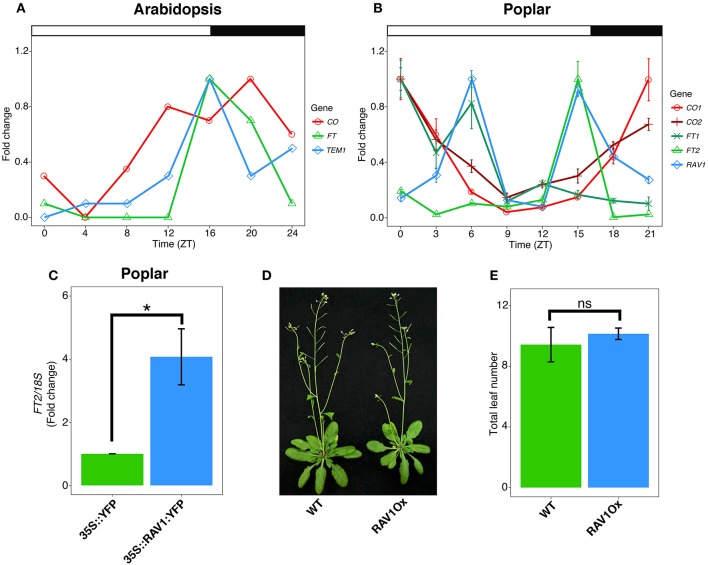

The mobile protein FT transmits photoperiod information from the leaf to apex to control Arabidopsis flowering (Corbesier et al., 2007). FT gene transcription is extremely sensitive to photoperiod changes. Long days enhance FT transcription and short days drastically reduce it. FT shows a robust diurnal gene expression pattern under long day conditions showing a peak of mRNA accumulation at the end of the day (Figure 1A). This temporal pattern is critical to distinguish photoperiod information from other signals (Krzymuski et al., 2015). The combined actions of circadian clock-controlled activators and repressors sustain this tight FT diurnal expression in Arabidopsis (reviewed in Song et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Divergent temporal expression pattern and molecular function of Poplar TEM/RAV1. (A) Representative diurnal mRNA expression pattern of Arabidopsis FT, CO and TEM under long day conditions. (B) Diurnal mRNA expression of FT1, FT2, CO1, CO2, and RAV1 examined through qRT-PCR of hybrid poplar (Populus tremula x alba) wild-type leaves under long day conditions. (A,B) Gene expression was relativized to the maximum value for each gene and represented as fold change to compare the diurnal patterns. Noteworthy, maximum expression peaks of FT2 and CO1 are 24 and 3.5 times higher than FT1 and CO2, respectively. Time is expressed in hours from dawn (ZT, zeitgeber time). Error bars indicate the standard deviation corresponding to three technical replicates. (C) FT2 mRNA expression at ZT15. qRT-PCR analysis performed on hybrid poplar leaf samples transiently expressing 35S::RAV1:YFP::tNOS and 35S::YFP::tNOS (control) constructs. Data are represented as the mean ± se of three independent experiments. Asterisk indicates significant differences between the RAV1 overexpressing (Ox) construct and control (t-test, P < 0.05). (D) Representative picture showing the flowering of wild type and chestnut RAV1Ox Arabidopsis plants grown for 5 weeks under long day conditions. (E) Flowering time of wild type and chestnut RAV1Ox Arabidopsis plants obtained by counting the total leaf number at bolting transition of plants grown under long day conditions (n = 12). Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the mean. n.s., not significant (t-test, P > 0.05).

Two poplar orthologs of Arabidopsis FT have been identified. These show different spatio-temporal pattern of gene expression whereby FT1 is mainly expressed in stem and bud tissues at the end of winter, and FT2 expression occurs during the growing season mainly in leaf tissues (Pin and Nilsson, 2012). Remarkably, poplar FT2 mRNA levels indicate conserved diurnal expression and photoperiod responses as in Arabidopsis (Böhlenius et al., 2006; Ibáñez et al., 2010; Hsu et al., 2011; Figure 1B). Moreover, natural variation across a latitudinal gradient suggests diurnal FT2 expression is locally adapted to the day length regime (Böhlenius et al., 2006). Further, the ectopic expression of FT2 in poplar has been noted to induce a dramatic delay in growth cessation. Conversely, FT2 downregulation significantly speeds up growth cessation (Böhlenius et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2011). These studies have shown the conserved role of poplar FT2 as a mediator of the photoperiod signaling required for shoot apical growth. Whether mobile FT2 transfers photoperiod information to the poplar shoot apical meristem (SAM) is unknown. However, recent genetic studies indicate that trafficking of FT, or an FT-dependent signal, to the SAM is mediated by plasmodesmata (Tylewicz et al., 2018). Downregulation of FT2 is necessary but not sufficient for poplar growth cessation. Resman et al. (2010) showed that the timing of growth cessation involved additional downstream events to FT2. However, whether these operate under the control of an FT-dependent PTM mechanism remains to be investigated.

Diurnal patterns of poplar CONSTANS and RAV1/TEMPRANILLO suggest an alternative mechanism of transcriptional FT2 regulation

The balance between the transcriptional activation role of CONSTANS (CO) and the repressive activity of TEM is critical to maintain adequate FT mRNA levels (Suárez-López et al., 2001; Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008). CO expression is controlled by the circadian clock, and diurnal transcriptional activation of CO precedes the activation of FT under long day conditions (Figure 1A). Mutations in lhy-7 and lhy-20, which shorten the clock period, have been detected to induce the early timing of CO expression and high levels of FT (Park et al., 2016). Hence, the diurnal matching of CO and FT expression patterns is important to control Arabidopsis flowering. CO protein levels are also diurnally regulated. Accordingly, during daylight hours, CO protein levels are maintained, while in the dark, CO levels are reduced contributing to FT downregulation (Valverde et al., 2004). Moreover, the repression of FT is transcriptionally controlled by TEM, a transcription factor related to APETALA 2 and VIVIPAROUS-1 (RAV1), which directly binds the FT promoter (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008). TEM and FT are co-expressed, showing peak mRNA accumulation at the day-night transition when days are long (Castillejo and Pelaz, 2008; Osnato et al., 2012; Figure 1A).

Poplar orthologs of CO have been identified and functionally implicated in the photoperiodic regulation of poplar shoot growth and flowering (Böhlenius et al., 2006). Simultaneous downregulation of poplar CO1 and CO2 correlates with reduced levels of poplar FT2 leading to accelerated growth cessation under short day conditions (Böhlenius et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, the ectopic expression of CO gives rise to constitutively high levels of FT leading to early flowering under conditions of both long and short days. Consequently, in these plants, high-levels of CO expression are sufficient to promote flowering (Putterill et al., 1995). In contrast, the overexpression of poplar CO1 or CO2 orthologs was found neither to upregulate FT2 nor delay growth cessation under conditions of short days in poplar (Hsu et al., 2012), suggesting that FT2 repression is dominant under short day conditions. Moreover, diurnal expression patterns of poplar CO1 and CO2 show an anti-phase temporal pattern relative to FT2, indicating an alternative mode of action to the Arabidopsis model (Figure 1B). Recently, Ding et al. (2018) showed that GI contributes to poplar photoperiodic control of shoot apical growth via strong direct FT2 activation, whereas in Arabidopsis, GI strongly activates both CO and FT (Sawa and Kay, 2011; Ding et al., 2018). Poplars overexpressing GI show delayed short day-induced growth cessation indicating its predominant role as an activator of FT over CO (Ding et al., 2018).

Interestingly, a poplar RAV1 ortholog of the TEM gene has been also identified (Moreno-Cortés et al., 2012). QRT-PCR expression analysis of poplar RAV1 has revealed a different diurnal pattern from that observed for Arabidopsis TEM (Figures 1A,B). Thus, in leaves, poplar RAV1 shows two mRNA peaks, the first in the morning and the second in the evening, the later overlapping with the FT2 peak (Figures 1A,B). Unexpectedly, in a transactivation assay in poplar leaf tissues, the overexpression of RAV1 led to FT2 activation (Figure 1C). Supporting this observation, the overexpression of the chestnut RAV1 ortholog of TEM did not cause delayed flowering in Arabidopsis (Moreno-Cortés et al., 2012, Figures 1D,E). These data suggest that hybrid poplar and chestnut TEM orthologs do not operate as in Arabidopsis.

While the expression pattern and function as an integrator of photoperiodic information of FT2 is well-conserved in Arabidopsis and poplar (Böhlenius et al., 2006; Hsu et al., 2006, 2011; Tylewicz et al., 2015, 2018), some known FT2 regulators show different modes of action. This suggests that the molecular framework for poplar seasonal growth could involve additional players with particular and diverged features.

Photoperiod signaling downstream from FT2, controls the rate of shoot apical cell proliferation (Karlberg et al., 2010). FT2 targets a poplar ortholog of Arabidopsis APETALA1, Like-AP1 (LAP1), via interaction with the FLOWERING LOCUS D poplar ortholog (FDL1) (Tylewicz et al., 2015). LAP1 activity maintains shoot vegetative growth via direct regulation of AINTEGUMENTA LIKE 1 (AIL1) transcription factor (Azeez et al., 2014). Interestingly, the ectopic expression of LAP1 in poplar does not promote early flowering as shown for Arabidopsis AP1, pointing to diverged features for LAP1 in poplar (Mandel et al., 1992; Azeez et al., 2014).

Diurnal gene expression of height-associated SNPs uncovers potential photoperiodic regulators of poplar shoot apical growth

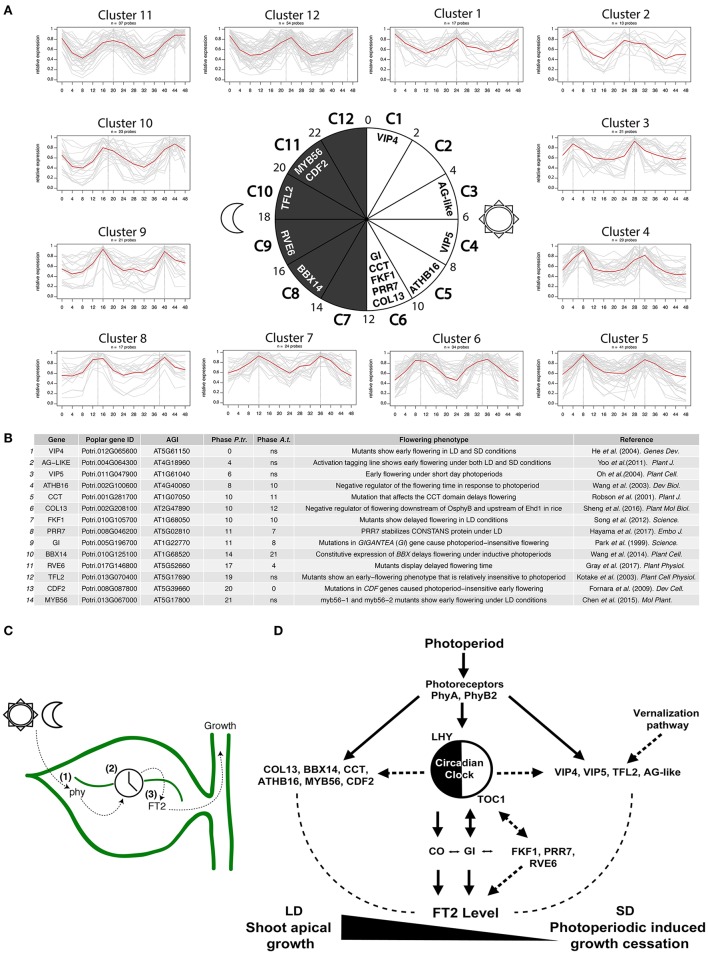

To examine whether the diurnal regulation of poplar shoot apical growth involves additional conserved known Arabidopsis flowering time regulators, we explored the diurnal expression of genes showing height-associated SNPs (Mockler et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2014). A total of 17% of genes associated with height showed robust diurnal rhythms of transcription over a 48 h period, indicating the requirement of diurnal gene expression for poplar shoot apical growth. We detected clusters of genes showing all possible diurnal expression patterns, indicating no specific phase enrichment in diurnally-controlled height increase (Figure 2A). Individual clusters were examined for poplar orthologs of flowering time genes that have been attributed a regulating role in the transition from vegetative growth to flowering in Arabidopsis. This led to the identification of 14 genes, whose altered expression in Arabidopsis gives rise to a variation in flowering time (Figures 2A,B). Interestingly, orthologs of the Arabidopsis clock-controlled GI, PRR7, FKF1, and REVEILLE 6 (RVE6) confirmed the role of the circadian clock in the regulation of shoot apical growth. Similarities in timing of mRNA accumulation peaks shown by Arabidopsis GI, FKF1, and PRR7 and the poplar orthologs suggest conserved transcriptional regulation despite the speciation process (Park et al., 1999; Song et al., 2012; Gray et al., 2017; Hayama et al., 2017) (Figures 2A,B). Phase differences in daily rhythms reflect local environmental constraints, which prompt diversification of molecular function contributing to phenotypic variation in natural populations (de Montaigu and Coupland, 2017). The poplar GI phase is delayed only 3 h compared with Arabidopsis GI and is synchronous with the daily timing of poplar FT2 activation (Figures 2A,B). The roles of FKF1, PRR7, and RVE6 in the photoperiodic regulation of poplar shoot apical growth requires further investigation. Physical interaction between FKF1 and GI has been reported in poplar, while the implications of this interaction remain unclear (Ding et al., 2018).

Figure 2.

Diurnal oscillations of poplar genes showing height-associated SNPs serve to unravel potential regulators of the photoperiodic control of shoot apical growth. (A) Clusters of poplar genes showing height-associated SNPs based on the phase of peak expression from the diurnal expression database. A total of 12 clusters were obtained covering the 24 h of the day and grouping phases every 2 h starting at cluster 1 (including phases 0 and 1). The central circadian circle shows the temporal succession of the clusters including identified poplar orthologs of known Arabidopsis flowering time regulators. (B) List of poplar genes orthologous to Arabidopsis flowering time regulators. Arabidopsis mutations in these genes gave rise to altered expression levels of FT. Poplar and Arabidopsis expression phases are shown (12:12 h light/dark, LDHC, cutoff 0.8). (C) Schematic representation of the leaf-localized photoperiod measurement mechanism in poplar. (1) Photosensory pathway, (2) circadian clock system, and (3) mobile photoperiodic mediator signal. (D) Schematic representation of poplar known and predicted photoperiod measurement components. Continuous lines represent experimentally supported links in poplar. Dashed lines represent experimentally supported links in Arabidopsis.

Additionally, we have identified 3 poplar CCT domain (CO, CO-like, and TOC1)-containing transcription factors designated COL13, BBX14, and CCT, showing both height-associated SNPs and robust diurnal expression (Robson et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2014; Sheng et al., 2016) (Figures 2A,B). Proteins carrying the CCT domain have been implicated in the photoperiodic regulation of FT in Arabidopsis. Moreover, the CCT motif has been shown to bind DNA and participate in protein-protein interactions (Wenkel et al., 2006; Gendron et al., 2012). Poplar COL13 and CCT show a phase similar to GI (Figures 2A,B). However, it remains to be determined whether they are also involved in the activation of FT2 in poplar.

A poplar ortholog of Arabidopsis CYCLING DOF FACTOR 2 (CDF2) was also found within cluster 11 (Figure 2A). This factor has been shown to transcriptionally repress CO (Fornara et al., 2009; Figure 2B). The overexpression of poplar CDF3 causes repression of FT2 and earlier growth cessation (Ding et al., 2018). Further, CDF2 was found to physically interact with GI and FKF1 in yeast two-hybrid assays, though in future work it remains to be elucidated if this interaction is meaningful (Ding et al., 2018).

A poplar ortholog of ARABIDOPSIS HOMEBOX 16 (ATHB16), which is a member of the HD-ZIP family of plant transcription factors, shows a similar expression phase in both plant species (Figures 2A,B). Functional studies have shown that ATHB16 acts as a negative regulator of flowering time in Arabidopsis (Figure 2B). Genetics studies have located ATHB16 downstream of the blue light signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2003). However, it is still not known if this pathway contributes to the control of poplar shoot apical growth.

We also identified a poplar ortholog of the Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB56, which has been shown to be a negative regulator of photoperiodic flowering time and FT expression in Arabidopsis (Chen et al., 2015). Interestingly, this poplar ortholog shares identical diurnal gene expression with the poplar ortholog of CDF2 and could thus be a negative regulator of poplar FT2 and growth cessation (Figures 2A,B). Contrary to findings in poplar, the diurnal expression of MYB56 showed no significant rhythmicity in Arabidopsis suggesting its different regulation in trees.

Remarkably, poplar orthologs of Arabidopsis VIP4 and VIP5, AG-like and TFL2, all associated with plant height, have also shown robust diurnal rhythms in poplar. However, diurnal variations in Arabidopsis VIP4, VIP5, AG-like, and TFL2 were found not to be significant, indicating their orthologous poplar genes have acquired robust diurnal expression (Figures 2A,B). Arabidopsis VIP4, VIP5, AG-like, and TFL2 have been attributed roles in flowering time and vernalization through the epigenetic regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) and FT, particularly for TFL2 (Kotake et al., 2003; He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2004; Yoo et al., 2011). It would be interesting to determine whether poplar orthologs of VIP4, VIP5, AG-like, and TFL2 participate in the regulation of shoot apical growth via rhythmic deposition and recognition of epigenetic marks in poplar.

Collectively, the available data have served to identify several poplar orthologs of Arabidopsis photoperiod-controlled flowering time regulators that could play a role in poplar shoot apical growth. Interestingly, we found key regulators of the vernalization pathway that show robust diurnal rhythms in poplar. This reveals that the transcriptional regulation of FT in Arabidopsis and poplar could share a larger molecular framework than was previously envisaged and new regulatory pathways (Figures 2C,D).

Concluding remarks

Poplar has a PTM mechanism that controls seasonal growth. This mechanism preserves the basic functions and molecular components of the mechanism of flowering time regulation known for Arabidopsis. Elements of the photosensory pathway, the circadian clock, and a mobile photoperiodic mediator are prerequisites for an adequate poplar growth cessation response (Figure 2C). Diurnal expression patterns serve to track the photoperiodic signal. Diurnally- expressed genes featuring SNPs associated with height show all possible diurnal phases. Divergent expression patterns of known and predicted PTM components relative to those of Arabidopsis suggest different modes of action in poplar. Interactions among photoreceptors, circadian clock system and FT2 regulation in poplar need further investigation. We here propose new potential candidates (Figure 2D). Among these candidates, we would highlight the poplar orthologs of epigenetic regulators of the Arabidopsis vernalization pathway. These factors show an unusually robust diurnal expression pattern in poplar, suggesting they could play a critical role in the photoperiodic pathway.

Author contributions

PT, IA, and MP planned and designed the research. PT, TH-V, and AM-C performed experiments and analyzed data. PT, JR-S, IA, and MP wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all colleagues whose work has not been cited because of space limitations. We acknowledge the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centers of Excellence in R&D 2017–2021 to CBGP.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by Grants AGL2014-53352-R, PCIG13-GA-2013-631630 awarded to IA and MP. The work of MP was supported by the Ramón y Cajal programme of MINECO (RYC-2012-10194). JR-S was funded by a FPU12/01648 fellowship and PT Ph.D. by a programme of CEI campus of the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (L1UF00-47-JX9FYF).

References

- Azeez A., Miskolczi P., Tylewicz S., Bhalerao R. P. (2014). A tree ortholog of APETALA1 mediates photoperiodic control of seasonal growth. Curr. Biol. 24, 717–724. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.02.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhlenius H., Huang T., Charbonnel-Campaa L., Brunner A. M., Jansson S., Strauss S. H., et al. (2006). CO/FT regulatory module controls timing of flowering and seasonal growth cessation in trees. Science 312, 1040–1043. 10.1126/science.1126038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bünning E. (1936). Die endogene Tagesrhythmik als Grundlage der photoperiodischen Reaktion. Ber. Dtsch. Dot. Ges. 54, 590–607. [Google Scholar]

- Castillejo C., Pelaz S. (2008). The balance between CONSTANS and TEMPRANILLO activities determines FT expression to trigger flowering. Curr. Biol. 18, 1338–1343. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Bernhardt A., Lee J., Hellmann H. (2015). Identification of Arabidopsis MYB56 as a novel substrate for CRL3(BPM) E3 ligases. Mol. Plant. 8, 242–250. 10.1016/j.molp.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L., Vincent C., Jang S., Fornara F., Fan Q., Searle I., et al. (2007). FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316, 1030–1033. 10.1126/science.1141752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montaigu A., Coupland G. (2017). The timing of GIGANTEA expression during day/night cycles varies with the geographical origin of Arabidopsis accessions. Plant Signal Behav. 12:e1342026. 10.1080/15592324.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Böhlenius H., Rühl M. G., Chen P., Sane S., Zambrano J. A., et al. (2018). GIGANTEA-like genes control seasonal growth cessation in Populus. New Phytol. 218, 1491–1503. 10.1111/nph.15087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L. M., Slavov G. T., Rodgers-Melnick E., Martin J., Ranjan P., Muchero W., et al. (2014). Population genomics of Populus trichocarpa identifies signatures of selection and adaptive trait associations. Nat. Genet. 46, 1089–1096. 10.1038/ng.3075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filichkin S. A., Breton G., Priest H. D., Dharmawardhana P., Jaiswal P., Fox S. E., et al. (2011). Global profiling of rice and poplar transcriptomes highlights key conserved circadian-controlled pathways and cis-regulatory modules. PLoS ONE 6:e16907. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornara F., Panigrahi K. C., Gissot L., Sauerbrunn N., Rühl M., Jarillo J. A., et al. (2009). Arabidopsis DOF transcription factors act redundantly to reduce CONSTANS expression and are essential for a photoperiodic flowering response. Dev. Cell. 17, 75–86. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frewen B. E., Chen T. H., Howe G. T., Davis J., Rohde A., Boerjan W., et al. (2000). Quantitative trait loci and candidate gene mapping of bud set and bud flush in Populus. Genetics 154, 837–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron J. M., Pruneda-Paz J. L., Doherty C. J., Gross A. M., Kang S. E., Kay S. A. (2012). Arabidopsis circadian clock protein, TOC1, is a DNA-binding transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 3167–3172. 10.1073/pnas.1200355109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman B. D. (2001). Mammalian photoperiodic system: formal properties and neuroendocrine mechanisms of photoperiodic time measurement. J. Biol. Rhythms 16, 283–301. 10.1177/074873001129001980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J. A., Shalit-Kaneh A., Chu D. N., Hsu P. Y., Harmer S. L. (2017). The REVEILLE clock genes inhibit growth of juvenile and adult plants by control of cell Size. Plant Physiol. 173, 2308–2322. 10.1104/pp.17.00109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayama R., Sarid-Krebs L., Richter R., Fernández V., Jang S., Coupland G. (2017). PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATORs stabilize CONSTANS protein to promote flowering in response to day length. EMBO J. 36, 904–918. 10.15252/embj.201693907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Doyle M. R., Amasino R. M. (2004). PAF1-complex-mediated histone methylation of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin is required for the vernalization-responsive, winter-annual habit in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 18, 2774–2784. 10.1101/gad.1244504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. T., Bucciaglia P. A., Furnier G. R., Hackett W. P., Cordonnier-Pratt M. M., Gardner G. (1998). Evidence that the phytochrome gene family in black cottonwood has one PHYA locus and two PHYB loci but lacks members of the PHYC/F and PHYE subfamilies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 160–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. T., Gardner G., Hackett W. P., Furnier G. R. (1996). Phytochrome control of short-day-induced bud set in black cottonwood. Physiol. Plant. 97, 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Howe G. T., Hackett W. P., Fumier G. R., Klevorn R. E. (1995). Photoperiodic responses of a northern and southern ecotype of black cottonwood. Physiol. Plant. 93, 695–708. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. Y., Adams J. P., Kim H., No K., Ma C., Strauss S. H., et al. (2011). FLOWERING LOCUS T duplication coordinates reproductive and vegetative growth in perennial poplar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10756–10761. 10.1073/pnas.1104713108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. Y., Adams J. P., No K., Liang H., Meilan R., Pechanova O., et al. (2012). Overexpression of CONSTANS homologs CO1 and CO2 fails to alter normal reproductive onset and fall bud set in woody perennial poplar. PLoS ONE 7:e45448. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. Y., Liu Y., Luthe D. S., Yuceer C. (2006). Poplar FT2 shortens the juvenile phase and promotes seasonal flowering. Plant Cell 18, 1846–1861. 10.1105/tpc.106.041038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez C., Kozarewa I., Johansson M., Ogren E., Rohde A., Eriksson M. E. (2010). Circadian clock components regulate entry and affect exit of seasonal dormancy as well as winter hardiness in Populus trees. Plant Physiol. 153, 1823–1833. 10.1104/pp.110.158220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez C., Ramos A., Acebo P., Contreras A., Casado R., Allona I., et al. (2008). Overall alteration of circadian clock gene expression in the chestnut cold response. PLoS ONE 3:e3567. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson P. K., Garcia M. V., Luquez V., Hall D., Jansson S. (2008). Nucleotide polymorphism and phenotypic associations within and around the phytochrome B2 locus in European Aspen (Populus tremula, Salicaceae). Genetics 178, 2217–2226. 10.1534/genetics.107.082354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M., Ramos-Sánchez J. M., Conde D., Ibáñez C., Takata N., Allona I., et al. (2015). “Role of the circadian clock in cold acclimation and winter dormancy in perennial plants,” in Advances in Plant Dormancy, ed J. V. Anderson (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ) 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Karve A. A., Jawdy S. S., Gunter L. E., Allen S. M., Yang X., Tuskan G. A., et al. (2012). Initial characterization of shade avoidance response suggests functional diversity between Populus phytochrome B genes. New Phytol. 196, 726–737. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlberg A., Englund M., Petterle A., Molnar G., Sjödin A., Bako L., et al. (2010). Analysis of global changes in gene expression during activity-dormancy cycle in hybrid aspen apex. Plant Biotechnol. 27, 1–16. 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.27.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kotake T., Takada S., Nakahigashi K., Ohto M., Goto K. (2003). Arabidopsis TERMINAL FLOWER 2 gene encodes a heterochromatin protein 1 homolog and represses both FLOWERING LOCUS T to regulate flowering time and several floral homeotic genes. Plant Cell Physiol. 44, 555–564. 10.1093/pcp/pcg091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozarewa I., Ibanez C., Johansson M. (2010). Alteration of PHYA expression change circadian rhythms and timing of bud set in Populus. Plant Mol. Biol. 73, 143–156. 10.1007/s11103-010-9619-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzymuski M., Andrés F., Cagnola J. I., Jang S., Yanovsky M. J., Coupland G., et al. (2015). The dynamics of FLOWERING LOCUS T expression encodes long-day information. Plant J. 83, 952–961. 10.1111/tpj.12938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel M. A., Gustafson-Brown C., Savidge B., Yanofsky M. F. (1992). Molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene APETALA1. Nature 360, 273–277. 10.1038/360273a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya J. P., Bhalerao R. P. (2017). Photoperiod- and temperature-mediated control of growth cessation and dormancy in trees: a molecular perspective. Ann. Bot. 120, 351–360. 10.1093/aob/mcx061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockler T. C., Michael T. P., Priest H. D., Shen R., Sullivan C. M., Givan S. A., et al. (2007). The DIURNAL project: DIURNAL and circadian expression profiling, model-based pattern matching, and promoter analysis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 72, 353–363. 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Cortés A., Hernández-Verdeja T., Sánchez-Jiménez P., González-Melendi P., Aragoncillo C., Allona I. (2012). CsRAV1 induces sylleptic branching in hybrid poplar. New Phytol. 194, 83–90. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04023.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R. J., Denlinger D. L., Somers D. E. (2010). Photoperiodism: The Biological Calendar, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nohales M. A., Kay S. A. (2016). Molecular mechanisms at the core of the plant circadian oscillator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 1061–1069. 10.1038/nsmb.3327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S., Zhang H., Ludwig P., van Nocker S. (2004). A mechanism related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Paf1c is required for expression of the Arabidopsis FLC/MAF MADS box gene family. Plant Cell 16, 2940–2953. 10.1105/tpc.104.026062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen J. E., Junttila O., Nilsen J., Eriksson M. E., Martinussen I., Olsson O., et al. (1997). Ectopic expression of oat phytochrome A in Hybrid aspen changes critical daylength for growth and prevents cold acclimatization. Plant, J. 12, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Osnato M., Castillejo C., Matías-Hernández L., Pelaz S. (2012). TEMPRANILLO genes link photoperiod and gibberellin pathways to control flowering in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 3:808. 10.1038/ncomms1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D. H., Somers D. E., Kim Y. S., Choy Y. H., Lim H. K., Soh M. S., et al. (1999). Control of circadian rhythms and photoperiodic flowering by the Arabidopsis GIGANTEA gene. Science 285, 1579–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M. J., Kwon Y. J., Gil K. E., Park C. M. (2016). LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL regulates photoperiodic flowering via the circadian clock in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol 16:114 10.1186/s12870-016-0810-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegoraro M., Gesto J. S., Kyriacou C. P., Tauber E. (2014). Role for circadian clock genes in seasonal timing: testing the bünning hypothesis. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004603. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin P. A., Nilsson O. (2012). The multifaceted roles of FLOWERING LOCUS T in plant development. Plant Cell Environ. 35, 1742–1755. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C. S., Minis D. H. (1964). The entrainment of circadian oscillations by light and their role as photoperiodic clocks. Am. Nat. 98, 261–294. [Google Scholar]

- Putterill J., Robson F., Lee K., Simon R., Coupland G. (1995). The CONSTANS gene of Arabidopsis promotes flowering and encodes a protein showing similarities to zinc finger transcription factors. Cell 24, 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A., Pérez-Solís E., Ibáñez C., Casado R., Collada C., Gómez L., et al. (2005). Winter disruption of the circadian clock in chestnut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7037–7042. 10.1073/pnas.0408549102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Sánchez J. M., Triozzi P. M., Moreno-Cortés A., Conde D., Perales M., Allona I. (2017). Real-time monitoring of PtaHMGB activity in poplar transactivation assays. Plant Methods 13:50. 10.1186/s13007-017-0199-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J. W., Nagatani A., Elich T. D., Fagan M., Chory J. (1994). Phytochrome, A., and Phytochrome B have overlapping but distinct functions in Arabidopsis development. Plant Physiol. 104, 1139–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resman L., Howe G., Jonsen D., Englund M., Druart N., Schrader J., et al. (2010). Components acting downstream of short day perception regulate differential cessation of cambial activity and associated responses in early and late clones of hybrid poplar. Plant Physiol. 154, 1294–1303. 10.1104/pp.110.163907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson F., Costa M. M., Hepworth S. R., Vizir I., Piñeiro M., Reeves P. H., et al. (2001). Functional importance of conserved domains in the flowering-time gene CONSTANS demonstrated by analysis of mutant alleles and transgenic plants. Plant J. 28, 619–631. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruonala R., Rinne P. L., Kangasjärvi J., van der Schoot C. (2008). CENL1 expression in the rib meristem affects stem elongation and the transition to dormancy in populus. Plant Cell 20, 59–74. 10.1105/tpc.107.056721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa M., Kay S. A. (2011). GIGANTEA directly activates Flowering Locus T in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 11698–11703. 10.1073/pnas.1106771108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng P., Wu F., Tan J., Zhang H., Ma W., Chen L., et al. (2016). A CONSTANS-like transcriptional activator, OsCOL13, functions as a negative regulator of flowering downstream of OsphyB and upstream of Ehd1 in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 92, 209–222. 10.1007/s11103-016-0506-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. H., Shim J. S., Kinmonth-Schultz H. A., Imaizumi T. (2015). Photoperiodic flowering: time measurement mechanisms in leaves. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 441–464. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043014-115555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. H., Smith R. W., To B. J., Millar A. J., Imaizumi T. (2012). FKF1 conveys timing information for CONSTANS stabilization in photoperiodic flowering. Science 336, 1045–1049. 10.1126/science.1219644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-López P., Wheatley K., Robson F., Onouchi H., Valverde F., Coupland G. (2001). CONSTANS mediates between the circadian clock and the control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature 410, 1116–1120. 10.1038/35074138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata N., Saito S., Saito C. T., Nanjo T., Shinohara K., Uemura M. (2009). Molecular phylogeny and expression of poplar circadian clock genes, LHY1 and LHY2. New Phytol. 181, 808–819. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas B., Vince-Prue D. (1997). Photoperiodism in plants. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tylewicz S., Petterle A., Marttila S., Miskolczi P., Azeez A., Singh R. K., et al. (2018). Photoperiodic control of seasonal growth is mediated by ABA acting on cell-cell communication. Science 08:eaan8576 10.1126/science.aan8576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tylewicz S., Tsuji H., Miskolczi P., Petterle A., Azeez A., Jonsson K., et al. (2015). Dual role of tree florigen activation complex component FD in photoperiodic growth control and adaptive response pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3140–3145. 10.1073/pnas.1423440112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde F., Mouradov A., Soppe W., Ravenscroft D., Samach A., Coupland G. (2004). Photoreceptor regulation of CONSTANS protein in photoperiodic flowering. Science 303, 1003–1006. 10.1126/science.1091761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. Q., Guthrie C., Sarmast M. K., Dehesh K. (2014). BBX19 interacts with CONSTANS to repress FLOWERING LOCUS T transcription, defining a flowering time checkpoint in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26, 3589–3602. 10.1105/tpc.114.130252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Henriksson E., Söderman E., Henriksson K. N., Sundberg E., Engström P. (2003). The Arabidopsis homeobox gene, ATHB16, regulates leaf development and the sensitivity to photoperiod in Arabidopsis. Dev. Biol. 264, 228–239. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser C. J. (1970). Cold resistance and injury in woody plants. Science 169, 1269–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenkel S., Turck F., Singer K., Gissot L., Le Gourrierec J., Samach A., et al. (2006). CONSTANS and the CCAAT box binding complex share a functionally important domain and interact to regulate flowering of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 18, 2971–2984. 10.1105/tpc.106.043299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovsky M. J., Kay S. A. (2002). Molecular basis of seasonal time measurement in Arabidopsis. Nature 419, 308–312. 10.1038/nature00996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo S. K., Wu X., Lee J. S., Ahn J. H. (2011). AGAMOUS-LIKE 6 is a floral promoter that negatively regulates the FLC/MAF clade genes and positively regulates FT in Arabidopsis. Plant, J. 65, 62–76. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04402.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]