ABSTRACT

Objective

This study investigates ultrasonography as an effective tool for localizing and measuring the depth and size of wooden foreign bodies to perform less invasive and easier surgery without the need for any additional radiological techniques.

Methods

Fifteen patients were operated to remove foreign bodies in the extremities in 2016. The side of the affected extremity, the material, size, and location of the foreign body and time of admission after injury were noted, along with CRP, WBC, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate; length of incision, surgery duration, and complications were evaluated.

Results

The mean patient age was 39.66 (range: 6 to 68). Of the total, 8 of the foreign bodies were in the plantar surfaces of the feet, 3 were in the cruris, 2 were in the palm of the hand, and 2 were in the fingers. All patients underwent ultrasound evaluation before surgery. The surgeries lasted less than 10 min in 13 (87%) of the cases and from 10 to 20 min in 2 cases. No complications were observed in any of the patients.

Conclusion

Delayed extraction of foreign bodies can lead to local infections. Ultrasonography can be a reliable option for diagnosing and localizing radiolucent foreign bodies such as wooden objects. Level of Evidence IV; Case series.

Keywords: Foreign bodies, Soft tissues, Ultrasonography

RESUMO

Objetivo

Neste estudo, procuramos mostrar que a ultra-sonografia é uma ferramenta eficaz para localizar e medir a profundidade e o tamanho dos corpos estranhos em madeira, a fim de realizar uma cirurgia menos invasiva e mais fácil, sem a necessidade de técnicas radiológicas adicionais.

Métodos

15 pacientes foram submetidos à cirurgia para penetração de corpo estranho nas extremidades em 2016. O lado da extremidade afetada, o material, tamanho e localização do corpo estranho e o tempo de admissão após lesão foram observados. CRP, WBC e taxa de sedimentação de eritrócitos também foram observados. O comprimento da incisão, duração da operação e complicações foram avaliados.

Resultados

A idade média do paciente foi de 39,66 (intervalo: 6 a 68). No total, oito de todos os corpos estranhos estavam no lado plantar dos pés, três estavam no crúis, dois estavam na palma da mão e dois estavam nos dedos. Todos os pacientes foram submetidos a avaliação ultra-sonográfica antes da cirurgia. A duração da operação foi inferior a 10 minutos em 13 (87%) dos casos e entre 10 a 20 minutos em dois casos. As complicações não foram observadas em todos os pacientes.

Conclusão

A extração retardada de corpos estranhos pode levar a infeções locais. A ultra-sonografia pode ser uma opção confiável para diagnosticar e localizar corpos estranhos radiolúcidos, como objetos de madeira. Nível de evidência IV; Série de casos.

Keywords: Corpos estranhos, Tecidos moles, Ultrassonografia

INTRODUCTION

Residual foreign bodies in extremities after penetrating, lacerating, or crush injuries are commonly encountered. The history of the injury and physical examination of the extremity can provide information, but is usually insufficient. If a residual foreign body is suspected, radiographic visualization is necessary; conventional X-rays, ultrasonography (US), computerized tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to obtain visual images of the foreign bodies. Radiopaque objects can be easily diagnosed with X-rays. One study found that diagnosis was missed by the initial treating physician in ٣٨% of patients. Metal was visible in all of the radiographic images, glass in 96%, and wood in just 15%.1Delayed diagnosis can lead to pain, soft tissue infection, delayed and damaged wound healing, and abscess formation. Additionally, delayed surgery can lead to increased neurovascular injury, blood loss, wider surgical incision, and iatrogenic complications.

Ultrasound evaluation does not expose patients to ionized radiation and is highly sensitive to detecting foreign bodies with different densities. It is also more cost effective compared to CT and MRI.2,3

This study included patients who sought treatment at our clinic for complaints of residual wooden foreign bodies. We aimed to show that ultrasonography is an effective tool for localizing and measuring the depth and size of wooden foreign bodies in order to perform less invasive and easier surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 15 patients (6 male and 9 female) who presented with foreign body penetration in 2016 were evaluated retrospectively. The study was approved in advance by the institutional review board (2016-KAEK-51) and all patients signed an informed consent form. The injured side, material and location of the foreign body, presentation time after injury, length, width and depth of the foreign body, WBC, CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate at the time of admission, size of the incision, duration of surgery and complications were all evaluated. (Table 1)

Table 1. Sample data.

| Age | Sex | Location | Depth of object | Length of object | Width of object | Time of admission | Symptoms | WBC | ESR | CRP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | M | R sole of the foot | 16 mm | 10 mm | 2 mm | 18th day | Pain | 8.47 | 25 | 2 |

| 2 | 6 | F | R sole of the foot | 5 mm | 6 mm | 1 mm | 5th day | Pain | 6.75 | 12 | 3 |

| 3 | 27 | M | R sole of the foot | 10 mm | 14 mm | 2 mm | 30th day | Pain, drainage | 7.53 | 14 | 9 |

| 4 | 68 | F | L leg | 30 mm | 50 mm | 20 mm | 42nd day | Pain, drainage | 7.82 | 85 | 6 |

| 5 | 37 | M | L sole of the foot | 14 mm | 8 mm | 3 mm | 24th day | Pain, swelling, redness | 9.45 | 16 | 2 |

| 6 | 65 y | M | R hand | 5 mm | 10 mm | 2 mm | 28th day | Pain, drainage | 8.34 | 26 | 2 |

| 7 | 52 | F | R leg | 23 mm | 51 mm | 19 mm | 16th day | Pain, drainage | 7.55 | 18 | 8 |

| 8 | 55 | M | R leg | 7 mm | 12 mm | 3 mm | 7th day | Pain | 6.62 | 6 | 1 |

| 9 | 34 | F | R hand | 5 mm | 5mm | 2 mm | 1st day | Pain | 7.83 | 8 | 1 |

| 10 | 21 | F | L sole of the foot | 4 mm | 6 mm | 2 mm | 2nd day | Pain | 8.2 | 10 | 1 |

| 11 | 58 | F | R hand | 5 mm | 4 mm | 2 mm | 10th day | Pain | 6.79 | 20 | 3 |

| 12 | 21 | F | L sole of the foot | 8 mm | 6 mm | 2 mm | 35th day | Pain, swelling | 9.17 | 28 | 6 |

| 13 | 45 | M | R hand | 4 mm | 10 mm | 3 mm | 12th day | Pain, swelling | 6.94 | 12 | 1 |

| 14 | 32 | F | R sole of the foot | 5 mm | 22 mm | 3 mm | 1st day | Pain | 7.88 | 10 | 1 |

| 15 | 16 | F | R sole of the foot | 12 mm | 28 mm | 2 mm | 1st day | Pain | 6.18 | 16 | 3 |

CRP: C-Reactive Protein; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; M: Male F: Female R: Right L: Left MM: Millimeter

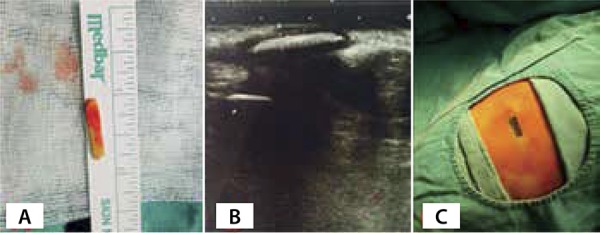

When the penetrating object was wooden and non-palpable or could not be observed superficially, patients underwent US imaging instead of X-ray, MRI, or CT. Wooden particles are visualized brightly in US, and the adjacent reactive inflammatory tissue is visualized as a hypoechoic region. (Figure 1B) A radiologist measured the length, width, depth, and longitudinal axis of the particles and marked the most superficial point of this axis on the skin. (Figure 1C) The radiologist also informed the surgeon about possible adjacent neurovascular structures. Patients were vaccinated against tetanus if more than 5 years had passed since previous vaccination. A first-generation cephalosporin was administered to all patients and all operations were performed under spinal or local anesthesia.

Figure 1. A. Extracted foreign body B. Ultrasound image of wooden foreign body C. Longitudinal axis of foreign body marked on the skin by the radiologist.

Fluoroscopy was not used in any of the cases. An incision was made over the marked skin and foreign bodies were easily accessed. (Figure 1A) In cases where infection was seen, soft tissue debridement was also performed and irrigated with 0.9% saline solution. Only one dose of cephalosporin was administered postoperatively when the case was not infected; in the other cases, antibiotic therapy was stopped after the clinical and laboratory findings returned to normal.

RESULTS

Mean patient age was 39.66 (range: 6 to 68). In total, 8 of the foreign bodies were in the plantar surfaces of the foot, 3 were in the cruris, 2 were in the palm of the hand, and 2 were in the fingers. The duration between injury and admission to the clinic was 1 day for 3 patients, 2–10 days in 4 patients, 11–30 days in 6 patients, and 31–45 days in 2 patients. All patients admitted to the clinic complained of pain; additionally, 4 patients reported drainage, and 3 patients reported redness and swelling. The mean WBC on admission was 7.70 (range: 6.18 to 9.45), mean sedimentation rate was 20.4 (range: 6 to 85), and mean CRP was 3.26 (range 1 to 9).

The mean length of the foreign bodies was 16.13 mm (range: 4 to 51), the mean width was 4.53 mm (range: 1 to 20 mm), and the mean depth was 10.2 mm (range: 4 to 30 mm). Surgical incisions were shorter than 1 cm in 8 cases, 1–2 cm in 5 cases, and 2–3 cm in 2 cases. The procedure lasted less than 10 mins in 13 (87%) of cases and 10–20 mins in 2 cases. Complications were not observed in any of the patients. In 4 infected cases, 11 (range: 10 to 14) days of antibiotic therapy was required.

DISCUSSION

Penetrating foreign body injuries to the extremities can be caused by various materials such as metals, glass, wood, or plastic objects. Radiologic visualization is required unless the residual material is palpable or can be seen from the outside. Conventional X-rays are useful for detecting metal and radiopaque materials, but are not sufficient to visualize radiolucent objects such as wood particles. One study including 200 patients found that X-ray could only detect 15% of wood particles.1 Ultrasound should therefore be the first option in penetrant injuries caused by wooden materials.4-7A recent meta-analysis found that US has 72% sensitivity and 92% specificity for identifying foreign bodies in soft tissues.8 Wooden materials are visualized as hyperechoic regions in US, and the adjacent soft tissue appears as hypoechoic due to reactive inflammation.5,9 (Figure 1B) US can effectively measure the length, width, thickness and depth of wood objects.9In our study, we were able to localize and measure the size of the particles in all cases. A cadaver study indicated that 3cc saline injection around foreign bodies can increase the sensitivity and specificity of US, although the authors were not able to detect a statistically significant increase.10

Leaving residual foreign bodies or partially extracting them can lead to persistent pain, cellulitis, abscess formation, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, necrotizing fasciitis, pseudotumor, and swelling.11-16 In order to extract foreign bodies, extended incisions over the entry point are possible, but are prone to serious risks and complications such as migration of the foreign bodies and residual fragmentation.17-19 Furthermore, extended dissection can cause further damage to adjacent soft tissue. A retrospective study in which all patients underwent surgery according to local physical examination found failure to completely extract radiolucent foreign bodies and persistent local infection in 2 patients.17 Consequently, preoperative evaluation of the length, width, depth, and number of objects with US and marking the skin along the long axis of the foreign bodies is essential in order to reduce incision length, procedure duration and most importantly, avoid leaving foreign bodies in the soft tissues.

Authors performing surgeries due to local inflammatory findings state that US depends on the individual radiologist.4,17 However, detection of wooden objects using US is a simple method that does not require further specialization. In one study, 10 nurses who received 2 hours of US training were able to detect wooden foreign bodies with 95% sensitivity.20

Some authors suggest extracting foreign bodies with US in the operating room.4,21 However, we believe that if preoperative evaluation is effectively performed, intra-operative US is not necessary; we did not require US assistance in any of our cases.

In our case series, the feet (53.33%) and hands (26.6%) were the most affected parts of the body, since they are open to external penetrant injuries. This finding is similar to other case series in the literature.17

The rough and organic structure of wooden particles provides a favorable environment for germs to reproduce.22 Metal objects can remain in tissues without causing any complications, but wooden particles can cause infections and consequently should be extracted. One study in the literature described a wooden particle becoming symptomatic after 8 years.11 In our case, the latest admission was 42 days after injury. Pain was observed in all our patients as an indicator of inflammation. Only 4 of the patients had elevated CRP levels which may have indicated infection. The mean time of admission after injury was 15.46 days, while in these 4 cases with elevated CRP levels, the mean time was 30.75 days. At the time of surgery, infected tissues such as abscesses were seen around the foreign particles in these 4 cases, demonstrating that each day which passes after trauma increases the likelihood of infection. All of these 4 cases were successfully treated by debridement of the adjacent soft tissues and oral antibiotic therapy.

This study has some weak points, namely the limited number of cases and retrospective nature. A prospective study could compare preoperative and postoperative findings, such as the diameters of foreign bodies measured by the US and the diameters of the extracted materials. Further prospective randomized controlled cadaver and animal studies can be performed to investigate the detection of different-sized wooden objects at different depths by US.

Retained foreign bodies are usually referred to orthopedic surgeons because of the workload in emergency and radiology departments; consequently, this topic must be dealt with by orthopedic surgeons from a legal perspective. The number of medical lawsuits is constantly increasing, and neglected foreign bodies can represent legal risk since these cases can present with delayed pain, swelling, drainage and loss of function in the extremity.23,24 One study in the United States revealed that 32 (59%) of 54 lawsuits against physicians related to wounds in a hospital emergency department in Massachusetts involved neglected foreign bodies in the extremities.24

Consequently, we recommend that patients should be informed of possible risk including the retention of foreign bodies despite surgery, and informed consent should be obtained before surgery. We also recommend meticulous preoperative planning and marking of the location of radiolucent foreign bodies with US to increase the success of the surgery.

CONCLUSION

Retained foreign bodies can lead to local infections; ultrasound evaluation and marking can be used preoperatively to diagnose, identify, and localize foreign bodies in the extremities.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson M, Newmeyer WL, 3rd, Kilgore ES., Jr Diagnosis and treatment of retained foreign bodies in the hand. Am J Surg. 1982;144(1):63–67. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham DD., Jr Ultrasound in the emergency department: detection of wooden foreign bodies in the soft tissues. J Emerg Med. 2002;22(1):75–79. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(01)00440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang R, Frazee B. Visual stimulus: splinter localization with ultrasound. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(3):294–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coombs CJ, Mutimer KL, Slattery PG, Wise AG. Hide and seek: pre-operative ultrasonic localization of non radioopaque foreign bodies. Aust N Z J Surg. 1990;60(12):989–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1990.tb07519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiels WE, 2nd, Babcock DS, Wilson JL, Burch RA. Localization and guided removal of soft-tissue foreign bodies with sonography. AJR Am J Roenigetiol. 1990;155(6):1277–1281. doi: 10.2214/ajr.155.6.2122680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haghnegahdar A, Shakibafard A, Khosravifard N. J Dent. 3. Vol. 17. Shiraz: 2016. Comparison between Computed Tomography and Ultrasonography in Detecting Foreign Bodies Regarding Their Composition and Depth: An In Vitro Study; pp. 177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turkcuer I, Atilla R, Topacoglu H, Yanturali S, Kiyan S, Kabakci N, et al. Do we really need plain and soft-tissue radiographies to detect radiolucent foreign bodies in the ED? Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(7):763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis J, Czerniski B, Au A, Adhikari S, Farrell I, Fields JM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasonography in Retained Soft Tissue Foreign Bodies: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(7):777–787. doi: 10.1111/acem.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockett MS, Gentile SC, Gudas CJ, Brage ME, Zygmunt KH. The use of ultrasonography for the detection of retained wooden foreign bodies in the foot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1995;34(5):471–478. doi: 10.1016/S1067-2516(09)80024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saul T, Siadecki SD, Rose G, Berkowitz R, Drake AB, Delone N, et al. Ultrasound for the evaluation of soft tissue foreign bodies before and after the addition of fluid to the surrounding interstitial space in a cadaveric model. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016;34(9):1779–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulati D, Agarwal A. Wooden foreign body in the forearm - presentation after eight years. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16(4):373–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidharthan S, Mbako AN. Pitfalls in diagnosis and problems in extraction of retained wooden foreign bodies in the foot. Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;16(2):e18–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laor T, Barnewolt CE. Nonradiopaque penetrating foreign body: “a sticky situation”. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29(9):702–704. doi: 10.1007/s002470050678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siegel IM. Identification of Non-Metallic Foreign Bodies in Soft Tissue: Eikenella corrodens Metatarsal Osteomyelitis Due to a Retained Toothpick: A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(9):1408–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanay O, Vaughan DJ, Diab M, Brownstein D, Brogan TV. Retained wooden foreign body in a child's thigh complicated by severe necrotizing fasciitis: A case report and discussion of imaging modalities for early diagnosis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(5):354–355. doi: 10.1097/00006565-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang Y, Zhu M, Qiu L. Ultrasonographic findings of gonarthritis caused by toothpick: a case report. J Clin Ultrasound. 2014;42(6):379–381. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtulmus T, Saglam N, Saka G, Imam M, Akpinar F. Tips and tricks in the diagnostic workup and the removal of foreign bodies in extremities. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2013;47(6):387–392. doi: 10.3944/aott.2013.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halaas GW. Management of Foreign Bodies in the Skin. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(5):683–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozsarac M, Demircan A, Sener S. Glass Foreign Body in Soft Tissue: Possibility of High Morbidity Due to Delayed Migration. J Glass Foreign Body in Soft Tissue: Possibility of High Morbidity Due to Delayed Migration. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(6):e125–e128. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkinson P, Madan R, Kendall R, Fraser J, Lewis D. Detection of soft tissue foreign bodies by nurse practitioner-performed ultrasound. 2Crit Ultrasound J. 2014;6(1) doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung A, Patton A, Navoy J, Cummings RJ. Intraoperative sonography-guided removal of radiolucent foreign bodies. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18(2):259–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ginsberg LE, Williams DW, Mathews VP. CT in penetrating craniocervical injury by wooden foreign bodies: reminder of a pitfall. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993;14(4):892–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, Caggiano R, Doyle MJ, Erdos MJ, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14(4):341–345. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser CW, Slowick T, Spurling KP, Friedman S. Retained foreign bodies. J Trauma. 1997;43(1):107–111. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]