Abstract

Young children construct a biological conception of death, recognizing that death terminates mental and bodily processes. Despite this recognition, many children are receptive to an alternative conception of death, which affirms that the deceased has an afterlife elsewhere. A plausible interpretation of children's receptivity to this alternative conception is that human beings, including young children, are naturally disposed to remember and keep in mind individuals to whom they are attached even when those individuals leave and are absent for extended periods. This disposition is reflected in the pervasive tendency to talk about death as a departure rather than a terminus. It also enables the living to sustain their ties to the dead, even if, in the case of death, the departure is permanent rather than temporary. Linguistic and developmental evidence for these claims is reviewed. Possible biological origins and implications for archaeological research are also discussed.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Evolutionary thanatology: impacts of the dead on the living in humans and other animals’.

Keywords: understanding, death, biology, religion, departure

1. Introduction

Psychological research on children's conception of death has focused on their emerging grasp of the biological nature of death, but more recently attention has also been paid to the way that many children and adults entertain an alternative conception. Despite acknowledging the termination of bodily and mental functions at death, they come to believe in some form of afterlife. I seek to explain humans' receptivity to that belief, especially given its apparently counterintuitive status. I argue that afterlife beliefs are supported by a wide-ranging human disposition to feel connected to, think about and talk about attachment figures, despite their physical absence.

2. Two conceptions of death

As they get older, children growing up in a variety of cultures realize that death inevitably comes to all living creatures and is an irreversible transformation [1]. The exact age at which they realize those biological facts varies but, barring cognitive pathology [2], children typically attain those insights by 10 years of age [3]. More recent research has focused on how children conceive the sequelae of death. I argue that many children, and adults, are inclined to adopt two parallel conceptions of death—a biological conception in which they think of the deceased as a dead corpse and an afterlife, or religious, conception in which they think of the deceased as someone who has departed this life but lives on elsewhere in some form.

Initial evidence for these parallel views was obtained by Harris & Giménez [4]. They presented 24 7-year-olds and 24 10-year-olds growing up in Madrid with two narratives about the death of a grandparent. In one narrative, the death was presented in a biomedical context. Thus, following the death of the grandparent, a doctor explained to a grandchild what had happened: ‘Your grandfather is dead now’. In an otherwise similar narrative, also involving the death of a grandparent, the death was presented in an afterlife context. Following the death of the grandparent, a priest rather than a doctor explained to a grandchild what had happened: ‘Your grandmother is with God now’. After answering questions about the continuation or cessation of particular bodily and mental processes, children were also asked two more generic questions: to say whether the body and the mind of the dead grandparent still functioned—or had ceased to function—and in either case, to explain their conclusion. These two generic questions were asked in the context of both the doctor and the priest narrative, yielding a total of four such probes.

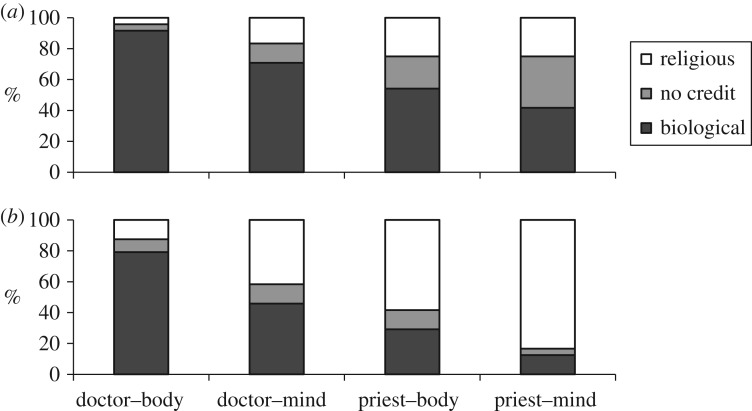

When children claimed that either the body or the mind had ceased to function and went on to explain that cessation in biological terms (e.g. ‘He has been eaten by worms; he has no body. He just has bones'; ‘If he is dead, nothing can work’), they were credited with a biological stance. By contrast, when they claimed that the body or mind continued to function and went on to explain that continuation in religious terms (e.g. ‘In Heaven everything can work even if she is dead’; ‘The soul keeps working’), they were credited with a religious or afterlife stance. Finally, when children failed to offer an explanation for their claim regarding cessation or continuity, or offered an explanation that did not cohere with that claim, they were given no credit for either stance. Figure 1 shows for each of the four probes the percentage of 7-year-olds (a) and 11-year-olds (b) credited with a biological stance, a religious stance or given no credit.

Figure 1.

Percentage of younger children (a) and older children (b) credited with a religious stance, a biological stance or given no credit in response to four probes, based on Harris [3].

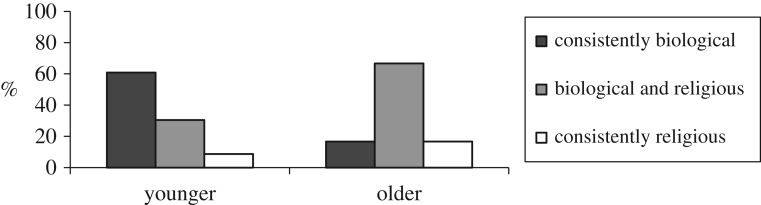

Inspection of figure 1 shows that, as expected on the basis of statistical analyses of children's replies to the questions about cessation versus continuity of function after death as well as their explanations [4], both age groups were influenced by the narrative context. They were more likely to adopt a biological stance for the two doctor probes than for the two priest probes. Conversely, they were more likely to adopt a religious stance for two priest probes than for the two doctor probes. In addition, the religious stance increased between 7 and 11 years, whereas the biological stance declined. One possible interpretation of this age change is that the religious stance increasingly displaces the biological stance. However, even among the 11-year-olds, the religious stance was not overwhelmingly adopted. For example, when asked to think about the functioning of the body in the context of the doctor narrative, most 11-year-olds adopted a biological stance. A different interpretation of the age change is that children do increasingly adopt a religious stance but in parallel with a biological stance. To assess this possibility more directly, Harris & Giménez [4] looked at the consistency of children's replies across the four probes. Individual children were assigned to one of the three categories depending on the pattern of their answers across the four probes: (i) consistently gave biological replies; (ii) gave a mix of biological and religious replies; or (iii) consistently gave religious replies. Figure 2 shows the percentage of 7- and 11-year-olds falling into each of these three patterns of responding.

Figure 2.

Percentage of 7- and 11-year-olds showing three patterns of responding across four probes, based on Harris [3].

Figure 2 shows that the majority of 7-year-olds gave consistently biological replies, whereas the majority of 11-year-olds gave a mix of biological and religious replies. By implication, children do not abandon the biological stance as they get older. Instead, they increasingly adopt the religious stance alongside the biological stance.

The study conducted by Harris & Giménez [4] was based on children growing up in a distinctive and relatively homogeneous culture, notably Catholic Spain. Arguably, the tendency to adopt two distinct ways of thinking about death is restricted to communities with a commitment to Catholicism or to Christianity. The tendency to adopt the two stances might also diminish or disappear if children strive for greater consistency as they get older. Subsequent findings cast doubt on both of these arguments. They show that the tendency to adopt a dual stance towards death is not confined to Christian cultures and persists into adulthood. Astuti & Harris [5] conducted a study with children and adults of the Vezo community in Madagascar. As in Spain, participants listened to two narratives about death. One involved a death in a biomedical context, whereas the other included cues to the ancestral afterlife. (Note that the Vezo believe that the dead take up a new form of life among the ancestors, from where they are able to influence the lives of the living.) Following each narrative, participants were presented with questions about the impact of death on the cessation or continuity of bodily and mental processes. The pattern of responding echoed that found in Spain. Participants were more likely to argue for the cessation of living processes following the biomedical narrative as opposed to the afterlife narrative. Indeed, in the biomedical context, a substantial minority of children and adults argued consistently for the cessation of all living processes. Nevertheless, the majority made claims of both cessation and continuity. This mixed response pattern was especially frequent in the afterlife context.

A possible interpretation of such mixed responding is that participants subscribe to a form of dualism. They think of the body in biological terms, emphasizing its cessation of function at death, whereas they think of the mind in religious terms, emphasizing its continuity of function. However, this account offers no explanation for the pervasive impact of narrative. Inspection of figure 1, for example, reveals that the type of narrative impacted children's replies whether they were questioned about the body or the mind.

More recent findings confirm that many participants display both a biological and a religious stance not just when they think about the body compared with the mind but also when they think about various different bodily processes or about various different mental processes. Watson-Jones et al. [6] compared beliefs about death among children and adults in the city of Austin, Texas, with those of children and adults in the city of Lenakel, on the island of Tanna, part of the Melanesian archipelago of Vanuatu. As in the studies in Spain and Madagascar, participants were primed with a narrative about death that provided either a biomedical context or an afterlife context. Following each narrative, participants were asked questions about various biological processes (e.g. ‘Do his eyes work or not?’; ‘Does his heart beat or not?’) as well as various psychological processes (e.g. ‘Does he see things or not?’; ‘Does he miss his children or not?’) and to explain their claim of cessation or continuity for each process. In line with the findings in Spain and Madagascar, the stance that participants adopted was influenced by the narrative. They produced more cessation claims and more biological explanations following the biomedical narrative compared with the afterlife narrative. Conversely, they produced more continuity claims and more religious explanations following the afterlife narrative compared with the biomedical narrative. Nevertheless, participants drew on both types of explanation when explaining the fate of particular psychological processes or when explaining the fate of particular bodily processes. Thus, the tendency to adopt a biological or a religious stance cannot be ascribed to a dualistic division between body and mind. It is found when participants think about each component of dualism—the body and the mind.

Finally, it is important to note that although evidence for the adoption of both a biological and a religious stance towards death has come from diverse cultures, this conception is unlikely to be universal. In communities where the surrounding culture provides little or no support for afterlife beliefs, it is likely that children and adults will adopt a predominantly biological stance, irrespective of the narrative context. Indeed, in a cross-national study, Lane et al. [7] found an effect of narrative on judgements of continuity versus cessation among participants in the USA but not in China.

Summing up across these various studies, they confirm that, depending on the surrounding culture, children and adults will often come to entertain two parallel stances towards death, a biological stance and an afterlife or religious stance. The narrative context in which a death is described and the type of process that participants are asked to think about (bodily processes versus mental processes) affect the probability of their adopting one stance rather than the other. Nevertheless, participants are prone to draw on both within a given narrative context and even for different processes of the same type. They readily recruit, and switch between, the two stances.

3. Missing persons

The findings described so far can be interpreted in terms of the following framework. In the course of childhood, children arrive at an understanding of the biological nature of death. They come to realize that, when someone dies, a living person turns into an insensate and unresponsive corpse that will decay and be disposed of. At the same time, children have the ability to think of deceased individuals as continuing to exist in some form. As noted by several authors [8–10], thinking about a deceased person is, in key respects, akin to thinking about a living person who has left for an extended period of time. Indeed, from an early age, children's social and emotional life is predicated on their ability to mentally represent the continued existence of various attachment figures (i.e. carers, siblings and friends)—despite their prolonged physical absence. This ability to represent absent persons presumably means that children are receptive to claims that, no matter what the fate of the corpse, the deceased person continues to exist elsewhere. The exact nature of that existence and of that elsewhere may be ultimately unknowable but when supplied with relevant testimony by the surrounding culture, children will be led to construct a suitable mental representation, just as they might do for a country they have never visited or a phenomenon they have never observed [11].

Children have the ability to represent absent persons before they have a comprehensive understanding of the biological inevitability and finality of death. Thus, even toddlers can think and talk about an absent attachment figure or anticipate a future reunion [12]. Children's emerging understanding of death confronts them with the fact that a separation brought about by death, unlike everyday separations, will be permanent rather than temporary. Yet children's continuing representation of the deceased is likely to be based on their memory of interactions with the living person—what Boyer [13] describes as the person-file system—and not just on their memory or representation of the insensate corpse. When children receive testimony about the afterlife, they are effectively offered further support for their representation of the ‘living person’ as existing elsewhere. He or she has departed this world for the afterlife, be it with God, in the Kingdom of Heaven, or among the Ancestors.

This account explains why many children and adults shift back and forth between two different but parallel stances towards death. They can adopt a biological stance towards the dead corpse—it no longer functions and will decay but, concurrently, they can also adopt an afterlife stance towards the absent person. He or she is assumed to exercise various mental and bodily powers, commensurate with local, cultural beliefs about the nature of that afterlife.1

In the sections below, I explore several implications of this account. First, if death is seen as a departure and not just as a biological terminus, this should be reflected in the euphemistic metaphors adopted in everyday talk about death. Second, the bereaved, including children, should voice their continuing psychological ties to the dead person even while recognizing that the separation that death entails is permanent. Third, the conception of death observed in humans invites two inter-related questions about the conception of death displayed by non-human primates. First, do non-human primates arrive at a piecemeal, empirically based understanding of death or the more comprehensive grasp of total cessation found among children? Second, if non-human primates display behaviours akin to human grief—especially immediately after the death of an individual to whom they were attached—what is the cognitive basis for that grief? Finally, if ideas about the afterlife are founded on the cognitive disposition to keep the deceased in mind despite their permanent absence, is that disposition also manifested in the increasing prevalence of burial sites in the course of human—and Neanderthal—history?

4. Metaphorical talk about death

If death is readily conceptualized in terms of a departure that ends our contact with the deceased, we may expect to find that departure implicated in the metaphors used to talk about death. Indeed, Lakoff & Turner [14] note that references to death as departure are common in English, fitting into a broader cognitive scheme in which life is conceived as a journey where birth is arrival, life is being present here and death is departure (e.g. ‘She passed away’, ‘He's gone’, ‘She's left us’, ‘He's no longer with us', ‘She's been taken from us’). Death is often viewed as the crossing of a threshold. A dying person is described as ‘slipping away’; a surgeon may ‘bring him back’ or ‘lose him’. Crossing that threshold implies that the deceased has left for another destination. He or she has ‘gone to a better place’, ‘gone to Heaven’, ‘gone to meet their Maker’ or ‘to join the Ancestors'. When the focus is not on the deceased but on the bereaved, they are described as ‘left behind’ and their experience is described in terms of a rupture in contact with the deceased, as in ‘they lost their father’. Funereal rituals are represented as a leave-taking, an opportunity for the bereaved to say a ‘last goodbye’.

The examples of metaphorical language described by Lakoff & Turner [14] are taken from English, including English poetry. However, subsequent analyses of a variety of other languages have confirmed that the metaphor of death as departure is found in Polish [15], Serbian [16], Spanish [17], Turkish [18], EkeGusii, a Bantu language of Western Kenya [19], Paiwan and Seediq, two Formosan languages and Mandarin [20]. It is unclear whether the metaphor is universal but evidently it is found in several unrelated languages.

Metaphorical talk about death might be restricted to adults. However, if Lakoff & Turner [14] are right in claiming that the metaphor of death as a departure is based on a relatively basic conceptual schema of life as a journey through the world with a final departure, we might also expect children to use that same metaphor. Silverman et al. [21] report findings supporting this speculation. They interviewed 125 children ranging from 6 to 17 years (M = 11.6 years) at four months, 1 year and 2 years after the death of a parent. Silverman et al. [21] focus on the content of children's replies, not on their use of metaphor. Nevertheless, the death as departure metaphor does appear in the answers that they quote, for example: ‘… I go to sleep fast so I won't think about his being gone’ (7-year-old); ‘He's not with me, and it hurts' (10-year-old); ‘… however, I don't want her to come back and be in such pain’ (12-year-old).

5. Continuing ties to the dead

Traditionally, post-Freudian clinical analyses of grief have implied that it involves the ‘work’ of detachment. However, later empirical research has shown that grief is often accompanied by strategies that maintain rather than sever a psychological tie to the deceased. In an influential study of widows (age range = 25–65 years) interviewed several times in the first year of their bereavement, Parkes [22] reported that in the first month, all the widows were preoccupied with thoughts of their dead husband and after a year, such preoccupation was still evident in the majority (68%). In the first month, most widows (73%) reported memories involving clear visualizations of their dead husband as he had been when he was alive and most (81%) continued to do so after a year. Indeed, most widows (73%) had a sense of their husband being near them during the first month and just over half (55%) continued to have that sense one year later. Not surprisingly, over the course of this first year of bereavement, there was a strong correlation among these three measures of a continuing psychological connection to the dead husband. Indeed, nearly half the widows engaged in activities likely to stir or sustain such connections. Most (86%) treasured objects associated with their husbands even if many also avoided certain items such as clothing or photographs for fear of provoking pangs of grief. Nearly half re-visited old haunts or returned to the cemetery or the hospital. Similar findings emerged in a study of young widows (under 45 years) in Boston [23]. One year after their bereavement, two-thirds reported that they continued to think of their husband ‘often’ or ‘a lot’. Many had the feeling that their husband was watching over them and reported deliberately invoking his presence when they were feeling depressed or unsure.

Reviewing these findings, Bowlby [24] proposed that an initial period of preoccupation and turmoil often gives way, not to detachment, but to the more comforting sense of a continuing psychological tie to the deceased. Recent longitudinal research has confirmed this pattern of sustained connection. In a large-scale study of widowhood, the majority of bereaved spouses reported thinking about their partner ‘daily or almost daily’ when interviewed six months after the loss. When re-interviewed 18 months after the loss, most reported thinking less often about their partner but they still did so ‘two or three times a week’ if not daily. At both time points, most spouses affirmed that thoughts and memories of their deceased partner had made them feel happy or at peace during the preceding months [25].

Do bereaved children also display a continuing psychological tie to dead attachment figures? Silverman and co-workers [21,26] interviewed bereaved children in the USA four months after the death of a parent. They found that most children (74%) said that their dead parent had gone to another place, typically Heaven. Children also talked about preserving their ties to the parent in various ways. Most said that they were still thinking about their dead parent several times a week (90%), thought that the dead parent was somehow watching them (81%) and kept something personal that belonged to their parent (77%), either in their room or on their person. The majority also said that they could talk about their dead parent with a family member (66%), had talked with friends (54%) and indeed reported speaking to the dead parent (57%). Despite the prevalence of these various strategies for maintaining ties with the dead parent, and even though half the children acknowledged having dreams in which the parent appeared to be alive, only a very small percentage (3%) reported that they could not believe that the death was real.

In summary, the findings reported by Silverman and co-workers [21,26] confirm that children think about and remain connected to a dead attachment figure while simultaneously acknowledging the reality of his or her death. By implication, many children cope with grief in the same manner as adults. They rarely deny the permanent loss that death brings about but nor do they become psychologically detached from the deceased parent.

6. Chimpanzees’ reactions to death

In the context of the special issue, the proposals above invite two sets of questions about the way that non-human primates conceive, and respond to, death. First, how far do chimpanzees interpret a given death in biological terms as a permanent cessation of function? Second, how do their psychological ties to a deceased group member impact their reactions, both immediately and in the longer term?

Observational reports of chimpanzees discovering a corpse [27–29] provide a preliminary, albeit partial, answer to the first question. They initially react with agitation and alarm. A suite of behaviours ensues: close investigation of the corpse via peering or smelling; subdued, and sometimes prolonged, visual inspection with limited manual contact and striking the corpse or lifting the limbs, as if testing for agency or responsiveness. These reactions imply that an encounter with the corpse of a conspecific is viewed as a major and disturbing deviation from ordinary interaction, a deviation that leads to uncertainty and empirical probing. Still, it is unclear whether the cessation of activity is understood—even by senior members of the group—in light of a broader biological framework in which death is understood as the permanent termination of all living functions.

Arguably, the pattern of behaviour just described reflects the shock of discovery. Via their investigation and inspection, group members may be ‘taking in’ an unanticipated event. Indeed, Anderson et al. [30] report a different constellation of reactions to the relatively peaceful, and arguably foreseeable, death of Pansy, a female chimpanzee aged 50+ years, living in a Scottish Safari Park. Group members groomed the ailing female in the days and hours before her death. Immediately after the death, they engaged in close inspection (pulling at her shoulder and arm, attempting to open her mouth) but only for a minute or two. That night, group members displayed signs of disturbed sleep (as indexed by postural shifts). In the next few days, their behaviour was subdued and, with the exception of Pansy's daughter, they avoided sleeping in the nesting platform where the death had occurred for several days. Overall, this set of observations suggests that Pansy's death was not unexpected. Still, even in this case, it is not clear that the long-term implications were fully understood.

The preceding observations of chimpanzees' reactions to death also indicate that individual reactions vary depending on the prior relationship with the deceased. For example, Teleki [27] notes that Godi, a male adolescent belonging to the same subgroup as the deceased, was the most persistent in making a distinctive type of call (i.e. a Wraa call), showed the greatest interest in the corpse and became agitated when others approached it. Stewart et al. [28] report that Mambo, the daughter of the dead Malaika, watched her body more than other group members. Van Leeuwen et al. [29] describe how Pan, an older male who had had frequent interactions with the deceased Thomas, grabbed a branch and suddenly lunged at Thomas's corpse causing other individuals to scatter and scream. Pan also inspected the corpse more than any of the other adult males. Finally, the daughter of Pansy remained close to her body on the night of her death—unlike other group members [30]. These individualized patterns imply that some primate reactions to an unresponsive corpse are triggered not just by a disturbing departure from the ordinary pattern of living behaviour but also by the severing of a social or affective bond. Still, it remains to be seen whether non-human primates distinguish between the permanent loss of an attachment figure caused by death and the prolonged separation from an attachment figure that can be caused by physical absence.2 Recall that the interviews with bereaved children suggest such a differentiation. They understood the permanence of death despite their continuing psychological ties to the dead parent.

7. The origins of burial practices

The evidence from non-human primates suggests that they experience a sense of loss and, arguably, some form of grief after the death of a group member. Still, it is important to note the limits of that grieving process. There is no evidence of any systematic effort to dispose of, or bury, the corpse and no evidence of active efforts to remain connected with the deceased, for example by regular and repeated visits to the site of death.

By contrast, among anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals, there is persuasive evidence for deliberate, albeit highly regionalized, burial practices, starting in the Middle Palaeolithic ca 120 000 years ago and becoming more systematic, and eventually more cemetery-like, in the course of the Upper Palaeolithic, from approximately 30 000 years ago [31]. Reviewing this record, Stiner [32] emphasizes one emerging feature of many burial sites, notably their location within, or close to, spaces that were important to the living. There is some evidence of earlier mass graves, but these can be conservatively viewed as disposal sites, given their location in inhospitable caves or crevices at some distance from areas bearing clear signs of regular habitation.

From a psychological perspective, a key question is what led to the increasing prevalence of such burial practices. It is unlikely that burial became more widespread simply because of technological progress. There is no obvious change in the tool-based demands of burial over the initial 100 000 years. Second, granted that burial practices became more prevalent long after the emergence of anatomically modern humans, it is unlikely that cortically based changes can account for the later appearing behavioural change in burial practices [33]. Admittedly, those cortical changes may have underpinned the emergence of relevant cognitive capacities—such as the capacity for planning or mental time travel—but we need to look elsewhere if we are to explain the eventual onset and historical trajectory of the burial practices.

In the light of the analysis offered earlier, notably the distinction between a biological and an afterlife conception of death, two lines of speculation are worth considering. First, in the course of the shift from the Middle to the Upper Palaeolithic, insight into the nature of death as a biological terminus may have become increasingly consolidated. For example, increased insight into the irrevocability of death might have motivated both anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals to bury and memorialize the dead. However, it is not obvious what would have driven such increased insight or indeed exactly why any such biological insight would have translated into more systematic burial practices.

A second line of speculation is more promising. As argued above, contemporary human adults and children maintain, and seek to maintain, their psychological ties to the deceased in various ways. Over an extended period, they often think about the deceased, talk about them and retain their possessions as keepsakes. Burial in close proximity to the living is consonant with the tendency to keep deceased individuals in mind rather than to dispose of their corpse and forget them. Indeed, the proximity of a grave is likely to serve as a reminder to the bereaved of the deceased. In addition, burial of kin or of group members in the same grave or in contiguous graves might symbolize for the living the restoration of severed ties between dead individuals. Such practices could have gradually produced a ratchet effect in which the proximity of burial sites helped to sustain memories of the dead among the living; and in turn, the accumulation of those memories, perhaps amplified by verbal recollection of the dead, provided a communal mental framework for the living to engage in the planning and execution of burials. Eventually, in the context of sustained burial practices, a group or community with a shallow collective memory of its ancestors might elaborate and deepen its awareness of successive, antecedent generations.3

8. Conclusion

Death is indubitably a biological event and it is important to ask how far children acquire a coherent understanding of its nature, especially its causes and its terminal consequences for all living functions. However, many children do not conceive death as an exclusively biological event. Especially when considering the social and emotional ties between the living and the deceased, they represent death as a separation. They are prone to represent that separation, not in narrowly biological terms as the termination of living functions, but rather in terms of a departure by the deceased to another place. In many cultures, religious testimony offers support for that representation. This parallel stance towards death invites questions about the degree to which it is present or absent in non-human primates and its emergence in the course of prehistory.

Acknowledgement

I am very grateful to Rita Astuti for helpful comments on this paper.

Endnotes

On this view, the human conception of death, whether as a biological event or as a departure, is primarily aimed at making sense of other people's deaths rather than our own. By implication, existential insecurity about our own personal mortality is a marginal rather than a central aspect of the human conception of death.

In concrete terms, it is possible that non-human primates will behave similarly whether they register identifiable cues (e.g. a distinctive vocalization) that signal the return of an individual who has been temporarily absent or that signal the apparent return of an individual who is known to have died. By contrast, human beings, including children, would presumably be disturbed by any apparent ‘return from the dead’, given its inconsistency with their biological understanding.

It is noteworthy that such a ratchet effect is not inevitable. For example, among some hunter–gatherer groups, disposal of the body barely goes beyond the practical need to dispose of a rotting corpse. Moreover, following a death, camp is generally abandoned thereby precluding the cumulative effect of successive burials in the same location [34].

Competing interests

I declare I have no competing interests.

Funding

I received no funding for this study.

References

- 1.Kenyon BL. 2001. Current research in children's conceptions of death: a critical review. Omega 43, 63–91. ( 10.2190/0X2B-B1N9-A579-DVK1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson SC, Carey S. 1998. Knowledge enrichment and conceptual change in folkbiology: evidence from Williams syndrome. Cogn. Psychol. 37, 156–200. ( 10.1006/cogp.1998.0695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris PL. 2012. Trusting what you're told: How children learn from others. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press/Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris PL, Giménez M. 2005. Children's acceptance of conflicting testimony: the case of death. J. Cogn. Culture 5, 143–164. ( 10.1163/1568537054068606) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astuti R, Harris PL. 2008. Understanding mortality and the life of the ancestors in Madagascar. Cogn. Sci. 32, 713–740. ( 10.1080/03640210802066907) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson-Jones RE, Busch JTA, Harris PL, Legare CH. 2017. Does the body survive death? Cultural variation in beliefs about life everlasting. Cogn. Sci. 41, 455–476. ( 10.1111/cogs.12430) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lane JD, Zhu L, Evans ME, Wellman HM. 2016. Developing concepts of the mind, body, and afterlife: exploring the roles of narrative context and culture. J. Cogn. Culture 16, 50–82. ( 10.1163/15685373-12342168) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Proust M. 1992. In search of lost time, volume 5: the captive, the fugitive. London, UK: Chatto & Windus. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bering J. 2006. The folk psychology of souls. Behav. Brain Sci. 29, 1–46. ( 10.1017/S0140525X06009101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodge KM. 2011. On imagining the afterlife. J. Cogn. Culture 11, 367–389. ( 10.1163/156853711X591305) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris PL, Koenig M. 2006. Trust in testimony: how children learn about science and religion. Child Dev. 77, 505–524. ( 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00886.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris PL. 2016. Missing persons. In Art, mind, and narrative: themes from the work of Peter Goldie (ed. Dodd J.), pp. 190–206. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyer P. 2001. Religion explained: the evolutionary origins of religious thought. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lakoff G, Turner M. 1989. More than cool reason: a field guide to poetic metaphor. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuczoc M. 2016. Metaphorical conceptualizations of death and dying in American English and Polish: a corpus-based contrastive study. Linguist. Silesiana 37, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silaški N. 2011. Metaphors and euphemisms—the case of death in English and Serbian. Filološki Pregled 38, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crespo-Fernández F. 2013. Euphemistic metaphors in English and Spanish epitaphs: a comparative study. Atlantis 35, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Özçalişkan Ş. 2003. In a caravanserai with two doors I am walking day and night: metaphors of death and life in Turkish. Cogn. Linguist. 14, 281–320. ( 10.1515/cogl.2003.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyakoe DG, Matu PM, Ongarora DO. 2012. Conceptualization of ‘death as journey’ and ‘death as rest’ in EkeGusii euphemism. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2, 1452–1457. ( 10.4304/tpls.2.7.1452-1457) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AP-j. 2011. Metaphorical euphemisms of RELATIONSHIP and DEATH in Kavalan, Paiwan, and Seediq. Ocean. Linguist. 50, 351–379. ( 10.1353/ol.2011.0027) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman PR, Nickman S, Worden JW. 1992. Detachment revisited: the child's reconstruction of a dead parent. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 62, 494–503. ( 10.1037/h0079366) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parkes CM. 1970. The first year of bereavement: a longitudinal study of the reaction of London widows to the death of their husbands. Psychiatry 33, 444–467. ( 10.1080/00332747.1970.11023644) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glick IO, Weiss RS, Parkes CM. 1974. The first year of bereavement. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowlby J. 1980. Attachment and loss, vol. 3 loss: sadness and depression. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Nesse RM. 2004. Prospective patterns of resilience and maladjustment during widowhood. Psychol. Aging 19, 260–271. ( 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.260) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverman PR, Worden JW. 1992. Children's reactions in the early months after the death of a parent. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 62, 93–104. ( 10.1037/h0079304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teleki G. 1973. Group response to the accidental death of a chimpanzee in Gombe National Park. Tanzania. Folia Primatol. 20, 81–94. ( 10.1159/000155569) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart FA, Piel AK, O'Malley RC. 2012. Responses of chimpanzees to a recently dead community member at Gombe National Park, Tanzania. Am. J. Primatol. 74, 1–7. ( 10.1002/ajp.20994) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Leeuwen EJC, Mulenga IC, Bodamer MD, Cronin KA. 2016. Chimpanzees’ responses to the dead body of a 9-year-old group member. Am. J. Primatol. 78, 914–922. ( 10.1002/ajp.22560) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson JR, Gillies A, Lock LC. 2010. Pan thanatology. Curr. Biol. 20, R349–R351. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettitt P. 2011. The Palaeolithic origins of human burial. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stiner MC. 2017. Love and death in the Stone Age: what constitutes first evidence of mortuary treatment of the human body. Biol. Theory 12, 248–261. ( 10.1007/s13752-017-0275-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sterelny K, Hiscock P. 2017. The perils and promises of cognitive archaeology: an introduction to the thematic issue. Biol. Theory 12, 189–194. ( 10.1007/s13752-017-0282-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodburn J. 1982. Social dimensions of death in four African hunting and gathering societies. In Death and the generation of life (eds Bloch M, Parry J), pp. 187–210. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]