Abstract

Although grief is a natural response to loss among human beings, some people have a severe and prolonged course of grief. In the 1990s, unusual grief persisting with a high level of acute symptoms became known as ‘complicated grief (CG)’. Many studies have shown that people who suffer from CG are at risk of long-term mental and physical health impairments and suicidal behaviours; it is considered a pathological state, which requires clinical intervention and treatment. DSM-5 (2013 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn) proposed ‘persistent complex bereavement disorder’ as a psychiatric disorder; it is similar to CG in that it is a trauma- and stress-related disorder. In recent years, there has been considerable research on the treatment of CG. Randomized controlled trials have suggested the efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy including an exposure component that is targeted for CG. However, experts disagree about the terminology and diagnostic criteria for CG. The ICD-11 (International classification of diseases, 11th revision) beta draft proposed prolonged grief disorder as a condition that differs from persistent complex bereavement disorder with respect to terminology and the duration of symptoms. This divergence has arisen from insufficient evidence for a set of core symptoms and the biological basis of CG. Future studies including biological studies are needed to reach consensus about the diagnostic criteria for CG.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Evolutionary thanatology: impacts of the dead on the living in humans and other animals’.

Keywords: grief, complicated grief, prolonged grief disorder, persistent complex bereavement disorder, DSM-V, ICD-11

1. Introduction

Most people will experience the death of a loved one due to disease, disaster, accident, war, homicide or suicide. Although bereavement is inevitable, it leads to severe psychological suffering, and it sometimes profoundly changes one's way of living. Bowlby [1] stated: ‘Loss of a loved one is one of the most intensely painful experiences any human being can suffer. And not only is it painful to experience but it is also painful to witness, if only because we are so impotent to help. To the bereaved nothing but the return of the lost person can bring true comfort; should what we provide fall short of that it is felt almost as an insult’.

Given that death is an irreversible process, people have to withstand the feeling of sadness and continue living with it. However, in most cases, the bereaved do not require help from professional therapists; they gradually recover to normal life on their own. Freud [2] described the reaction to the loss of a significant other as ‘mourning (Trauer)’. He stated that mourning is a normal response, and that over time mourners relinquish the bond with the deceased by accepting their absence and transferring libido to others. The concept of mourning is similar to grief, which is a normal reaction to the death of a loved one and which has both psychological and physiological manifestations [3]. Freud [2] also indicated that mourning leads to a sequence of psychological processes that include reality testing. From the psychodynamic viewpoint, he explained that this process was susceptible to interference from external and internal conditions. External conditions include critical situations such as a severe disease of a family member or violent death. Internal conditions refer to a hostile or excessive relationship with the deceased and various psychological defence mechanisms including suppression of emotions and disbelief in the death to avoid distress. Mechanisms for an impeded grief process as suggested by Freud [2] have been examined in recent studies. Simon [4] proposed that the nature of the relationship with the deceased and the nature of death itself, such as sudden and violent death, were risk factors for the development of pathological grief. For Lobb et al. [5], cognitive behavioural conceptualizations including a negative view of the self and the world, and avoidance of emotional problems, predicted pathological grief. Lindemann [6] found that the Cocoanut Grove fire in 1942 led to delayed grief and distorted perceptions among some acquaintances of the victims; this pathological type of grief can be transformed to normal grief by appropriate intervention. More recently, grief researchers have sought to conceptualize unusual/pathological grief such as complicated grief (CG) [7,8], traumatic grief [9] and prolonged grief disorder (PGD) [10].

In the 2000s, based on empirical studies, the opinion that unusual/pathological grief represented by CG should be defined as a psychiatric disorder increased among grief researchers [8,10]. Accordingly, the American Psychiatric Association introduced ‘persistent complex bereavement disorder’ (PCBD) in the 2013 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn (DSM-5) [11]. At the same time, effective interventions for CG have been required following major man-made and natural disasters that have occurred in various parts of the world, such as the 9/11 incident, synchronized terrorist attacks and the Great East Japan Earthquake.

This review is based on empirical studies and systematic reviews from PubMed and Psycho INFO related to CG, PGD and PCBD mainly in the last two decades. It outlines the concept of normal grief based on attachment theory, development and arguments concerning diagnostic criteria for pathological grief, and recent advances in CG treatment.

2. What is ‘grief’?

Grief is primarily an emotional reaction to the loss of a loved one through death. A ‘loved one’ refers to a person with whom an individual shares a particularly strong emotional bond, including attachment figures and carers. Bowlby [1] drew parallels between the reaction following the death of the partner among adults and separation distress in infants who manifest protest, despair and detachment. He suggested that grief is essentially a reaction to the loss of an attachment figure. This ‘attachment theory’ view of grief has influenced many studies [12], supported by attachment mechanisms in various species and animals including cats, dogs, goats, non-human primates and elephants, which manifest grief-like reactions for a dead peer or family member [13]. In her book How animals grieve, King [13] describes examples such as a cat looking for its lost sister with plaintive cries and a group of elephants encircling the bones of a dead group leader, as if commemorating the deceased individual. It appears common for some animals as well as humans to experience grief due to the loss of an attachment figure.

The presence of grief among animals raises the question of the pertinence of grief for survival. In the case of an infant temporarily detached from the mother, it is beneficial for the infant to experience separation distress and to protest by crying in order to restore proximity or contact with her. However, when the separation is permanent, as in the case of a loved one's death, grief reactions such as longing and yearning are in vain; they do not reinstate the deceased individual and may interfere with forming new attachments [1]. In addition, if bereaved animals stay by the dead body when grieving, there may be increased risks of infection or predation. King [13] stated that manifestations of grief in animals indicate the possibility of a strong positive emotion—‘love’—for another individual, which means that grief itself may not be beneficial for survival, but an inevitable consequence of the rupture of a bond with a loved one or attachment figure [1]. According to Archer [14], grief is the cost of the overall adaptive separation reaction, and Parkes [15] described grief as a price to be paid for having a loving bond with another.

By contrast, also within an evolutionary framework, Nesse [16] proposed that grief has an adaptive function. He stated that grief is useful for coping with bereavement ‘by signaling others, by changing goals, by preventing future losses, by reassessing priorities and plans and other relationships' [16]. The view that grief promotes the reconstruction of life after bereavement is common in ‘relearning the world’; Attig [17] proposed that people who lose a loved one relearn and experience continuity and meaning in their life in a narrative manner.

This perspective on grief, wherein a person overcomes the painful emotions caused by bereavement and reconstructs their life to adapt to the world without the deceased, appears similar to post-traumatic growth [18] and resilience [19], and acknowledges that humans have the strength to recover and grow following a traumatic event.

3. Normal grief and the mourning process

In 1961, Engel [20] described grief as a deviation from a healthy or normal condition and argued that people recover from this pathological state to normal in a manner similar to the recovery process from a burn. In recent years, however, fewer grief researchers appear to share Engel's views. This is because attachment theory-driven views see grieving reactions, such as intense sorrow, longing, yearning and depression, as a typical manifestation of separation distress rather than a pathological reaction.

Many researchers including Parkes [15], Stroebe et al. [3] and Worden [21] interpret grief as a normal reaction, and for most people intense separation distress becomes manageable, and they gradually adapt to their new life without the deceased. For these researchers, the most important point that distinguishes normal grief from pathological grief is the mourning process. Therefore, it is important to understand what a normal mourning process entails.

Grief researchers have proposed various theories about the mourning process, including stage theory [1,15], task theory [21] and dual process theory [22] (see table 1 for a summary). The stage theory proposed by Bowlby [1] and Parkes [15] considered the adjustment to bereavement over a period of several weeks to a few months. This theory describes four stages: shock–numbness, yearning–searching, disorganization–despair and reorganization. This theory has been widely accepted by clinicians and the general population, in part owing to the stage theory of acceptance of death by Kübler-Ross [27]. However, it has also been criticized. Weiss [28] suggested that issues with this theory include lack of empirical testing, and that each stage implies intercorrelations within grief manifestations. For Neimeyer [25], the stage theory is prone to be misunderstood as implying that all people should go through all of the stages.

Table 1.

Summary of the mourning process models.

| model | authors | components of mourning process | summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| stage theory | Bowlby (1982) [1] |

|

this model focused on the natural emotional shift the findings of two recent studies [23,24] were inconsistent with this theory; however, the studies validated that the peak of emotions of grief is shifted over time |

| task theory | Worden (2008) [21] |

|

this model focused on the mourner's task of facing the situation

and actively coping with it the overall validity of this model has not been examined by empirical studies the importance of maintaining a connection with the deceased in order to adapt to the loss was supported by another study [25] |

| dual process model | Strobe & Schut (1999) [22] |

|

this model focused on the two coping strategies for stressors related to

grief the mourners recover from grief by oscillating between the two coping strategies in daily life some studies have attempted to validate this model. Chen et al. [26] supported the importance of this model in their study on disaster survivors |

In response to such criticisms, Stroebe et al. [3] pointed out that Bowlby did not imply these stages as a concrete model, and that his theory might be misunderstood. Maciejewski et al. [23] examined the relative magnitudes and patterns of post-loss changes over time on five grief indicators, including disbelief, yearning, anger, depression and acceptance, to assess consistency with Bowlby's stage theory. Their findings indicated that disbelief was the initial, dominant grief indicator. Acceptance was the most-frequently selected item, which increased throughout the study observation period. Yearning was the dominant negative grief indicator from 1 to 24 months after bereavement. The normal stages of grief following a natural death showed that negative grief indicators peaked within approximately six months post loss. This finding was inconsistent with the stage theory; however, it partly supported the peak of negative emotions according to Bowlby's stage theory. Holland & Neimeyer [24] also failed to fully corroborate the stage theory, although their finding was partly consistent with it in the short time period after the loss. These studies indicate that grieving emotions, such as yearning, anger and depression, did not shift stepwise, but their peaks transferred over time.

Worden [21] partly agreed with the phase or stage theory proposed by Bowlby [1] and Parkes [15] but suggested using the term ‘task’ in the mourning process, because whereas ‘phase’ implies a passive process, ‘task’ requires the bereaved to engage actively. He emphasized that most people faced and overcame the four basic tasks, namely acceptance of death, processing the pain, adjustment to the world without the deceased and acknowledging the continuing bond with the deceased over time [21]. The idea of the continuing bond contrasts with Freud's [2] view that people should transfer their ‘libido’ from the deceased to someone else through the mourning process. However, in recent years, there has been an increasing acceptance of the necessity of the continuing bond with the deceased for adapting to the loss [29].

Stroebe & Schut [22] proposed another theory to explain how people accept the death of a loved one and recover from distress in day-to-day life. They called these modes the dual process model of coping with bereavement. This model identifies two types of stressors, loss- and restoration-oriented, and a dynamic, regulatory coping process of oscillation, whereby the grieving individual at times confronts or avoids the different tasks of grieving. In daily life, the bereaved experiences both aspects; in other words, people repeat confrontation and avoidance with the distress related to death. This pattern is critical in accepting the death and starting a new life without the deceased. This model is characterized by recognizing the importance of avoidance of grief work. The role of avoidance in the recovery process from acute grief seems to be different from that in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The emotional processing theory of PTSD proposed by Foa & Kozak [30] regards harmless stimuli as a non-functional factor interfering with the natural recovery process. This means that memories related to the patient's traumatic event are seen as in the past, and at present it is not necessary to avoid them. By contrast, the bereaved individual is forced to confront the reality of the loss of the loved one; death cannot be treated as a past event because it is permanent. Parkes [15] stated that the reality of death is too catastrophic to be quickly accepted by the bereaved. Therefore, the bereaved lower their distress levels through adaptive avoidance, similar to protective exclusion and reappraisal of the meaning of death, while oscillating between avoidance and confrontation. Validity of the dual model process in different contexts with various types of bereavement has been addressed in several studies [26,31,32]. Chen et al. [26] reported that six mothers who lost their children in the 2008 China earthquake primarily coped with loss-oriented stressors and shifted their focus to restoration-oriented stressors to deal with the situation over time.

4. Is CG a mental disorder?

Usually, grief follows a natural course, and people make a compromise with their loss and move onto their new life. However, for some, painful yearning and longing persist. Freud [2] considered any mourning that deviated from the usual process as not pathological, and he viewed melancholia as a distinct disorder from mourning.

At present, the concept of pathological grief is widely accepted among researchers [3,7–11]. Grief that deviates from the normal process is variously referred to as delayed grief [6], distorted grief [6], CG [7,8], traumatic grief [9], PGD [10] and PCBD [11]. One of these attracted considerable attention among researchers in the 1990s. Stroebe et al. [3] identified some of its common features and summarized CG as follows: ‘a clinically significant deviation from the (cultural) norm in either (a) the time course or intensity of specific or general syndromes of grief and/or (b) the level of performance in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning’.

The development of a validated scale for CG has stimulated empirical studies. Prigerson et al. [33] developed the inventory of CG (ICG), which is a self-administered scale with 19 items. As a result of the availability of a validated CG scale, epidemiological studies have revealed the clinical status of CG, including prevalence, risk factors and prognosis. Additionally, various scales such as ICG-R [33] and the brief grief questionnaire [34] were developed and used to measure the prevalence of CG. In a recent meta-analytic study [35], the estimated prevalence of CG among mourners was 9.8% (95% CI: 6.8–14.0%).

The issue of whether or not CG is a psychiatric disorder has been discussed in the past two decades. According to Prigerson et al. [10] and Shear et al. [8], CG—which Prigerson et al. [10] termed ‘PGD’ —is a mental disorder which requires providing treatment to the patient for the following reasons.

(a). The symptoms of CG are outside the scope of usual grief

The characteristic symptoms of CG include intense yearning, longing or emotional pain, frequent preoccupying thoughts and memories of the deceased person, a feeling of disbelief or inability to accept the loss and difficulty imagining a meaningful future without the deceased person. Many of these symptoms are similar to the acute phase of normal grief. Acute grief reactions such as yearning, longing and pangs of sadness usually diminish with time. Maciejewski et al. [23] reported that in the normal stages of grief following a natural death, the grief indicators peaked including yearning, anger and depression within approximately six months post loss. However, the symptoms of CG continue for a prolonged period of time. Among bereaved adults of the 11 September attack in New York, 43% met the criteria for CG 2.5–3.5 years after the event [36]. Some symptoms of CG such as excessive avoidance of reminders of the loss, constant preoccupation with the deceased and excessive survivor's guilt lead to dysfunctional thoughts, maladaptive behaviours and emotion dysregulation [8]. Furthermore, CG is associated with a variety of symptoms of poor physical health, mental problems and social dysfunction, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, cancer, headache, flu, suicidal ideation [37,38], low subjective health [39], various psychiatric symptoms [39,40], poor quality of life [39,41] and reduced vitality [40].

(b). CG differs from responses to a common stressor and other mental disorders

The prevalence of CG among the general population worldwide ranges from 2.4% in Japan [42] to 6.7% in Germany [43]. This means that only a small proportion of the bereaved population develops CG. Studies have reported that the prevalence of CG rises following traumatic events such as homicide (22% [44]) and terrorist attacks (43% [36]). CG often exists with other psychological co-morbidities including major depressive disorder (MDD) and PTSD [34,44,45]. The lifetime prevalence of a co-morbid disorder among the patients with CG is 84.5%, with the most prevalent being depression (71.8%) [45]. In recent years, however, it has generally been thought that CG is distinguishable from MDD and PTSD. The bereaved with CG suffers from intrusive memories of the loved one's death and avoids memories and reminders related to the loss. These symptoms of intrusion and avoidance are also seen in those with PTSD, particularly in the case of a traumatic death. However, patients with PTSD do not feel sadness but are fearful of trauma reminders, and they never seek proximity to the event-related situations or memories [8,46]. MDD has some features in common with CG, including feelings of sadness, guilt, suicidal ideations, decline in interest in daily and social life, and social isolation. Although symptoms of MDD are widespread across many aspects of life, CG symptoms are restricted to the deceased [8,46]. Furthermore, the finding that antidepressants are not effective for CG [47,48] underlines the difference between depression and CG. The diagnostic overlap between CG, MDD and PTSD has been reported to be modest [34,44].

(c). CG is universal across nations and cultures

There has been considerable research on CG among various cultures and nations, including both Western [43,45,49] and Eastern countries [26,42].

(d). CG has diagnostic validation in biological studies and responds to therapy

O'Connor et al. [50], in an fMRI study, suggested that the brain region related to CG was a reward system including the nucleus accumbens, which differed in reactivity to grief-related stimuli between CG and non-CG patients. Treatment studies have demonstrated that cognitive behavioural therapies designed for CG are more effective than other, non-specific therapies including interpersonal therapy [46,47] and supportive counselling [51].

(e). A diagnosis of CG might have more advantages than disadvantages

One of the reasons for opposing the view of CG as a mental disorder is the risk of regarding normal grief as pathological and stigmatizing the bereaved [3,52]. However, based on their experience and the results of the study by Johnston et al. [53], Shear et al. [8] suggested that many people were relieved to know that their symptoms had a name and were treatable. A field study by Prigerson et al. [10] found that a CG diagnosis could relieve the anxiety in bereaved individuals who feared a total mental and emotional breakdown.

In terms of cost, considering CG as a mental disorder might be advantageous. In Japan, unless diagnosed as a psychiatric disorder, a mental problem is not recognized for medical insurance. If CG were included as one of the psychiatric disorders, like PTSD, the burden of treatment costs to the patient with CG would be reduced.

5. Complications regarding diagnostic criteria for CG

Based on multiple studies on CG, in 2013, the American Psychiatric Association considered ‘CG’ as a psychiatric disorder and named it ‘PCBD’ in the DSM-5 [11]. PCBD is seen in other specific trauma- and stress-related disorders, and its diagnostic criteria were described in the chapter on conditions for future study [11]. It was also mentioned that grief researchers had not reached consensus regarding diagnostic criteria.

Prior to the revision of DSM-IV TR to DSM-5, two sets of diagnostic criteria were published. Prigerson et al. [54] used the diagnostic name PGD rather than CG. Shear et al. [8] continued using the term ‘CG’, arguing that the notion of ‘complication’ implied the nuance of interference with the natural process of recovery; CG was thus a commonly used term in the literature.

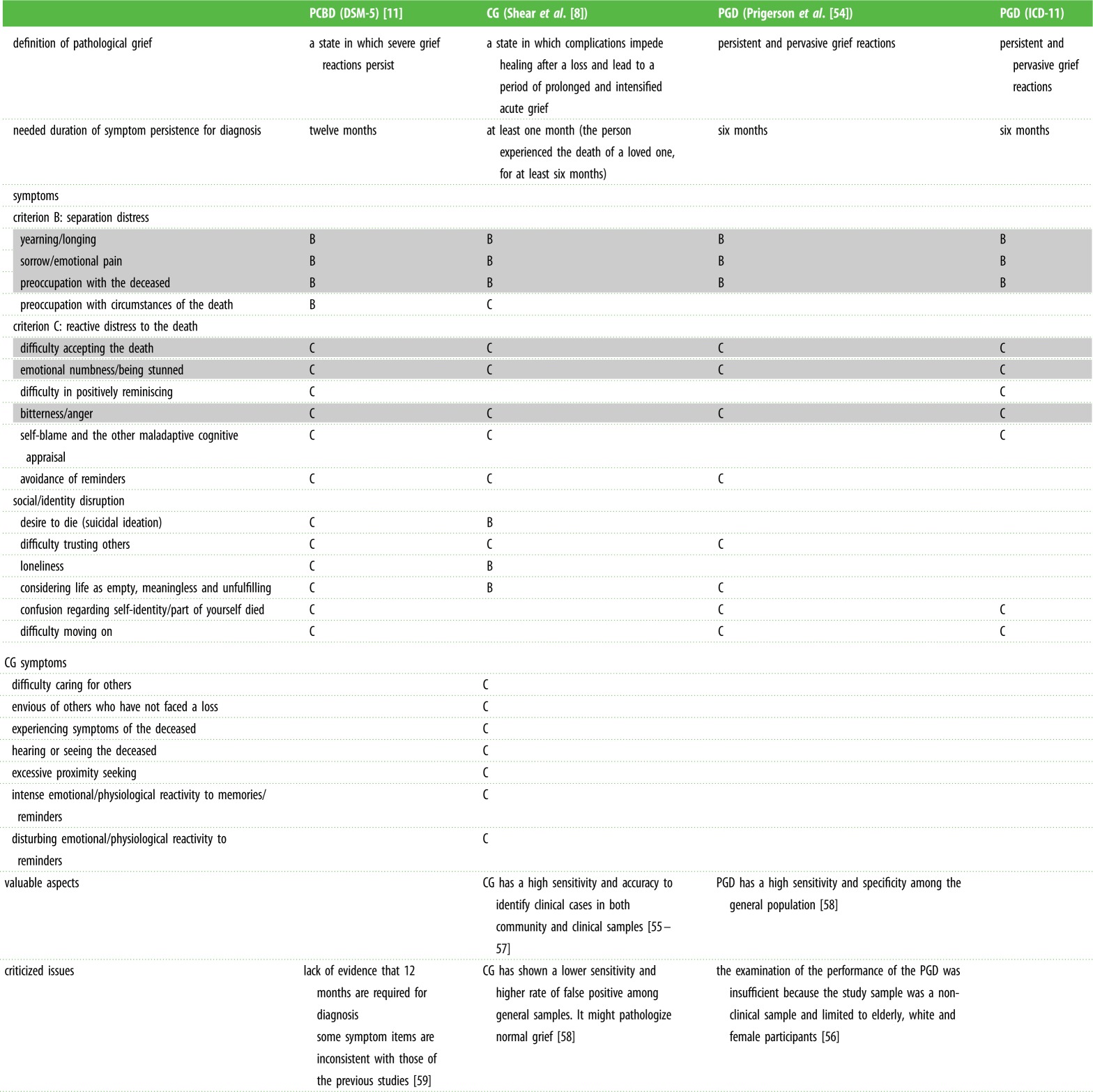

The diagnostic criteria for CG, PGD and PCBD share core symptoms of separation distress, including persistent yearning/longing, emotional pain and preoccupation with the deceased (table 2). However, the most important difference among them is the duration of the symptoms. The diagnostic criteria for PCBD require persistent symptoms for at least 12 months [11], compared with six months in PGD [54] and CG [8]. In ICD-11, which is scheduled to be revised in 2018, PGD will be defined as a condition that persists for six months (ICD-11 beta draft, December 2017).

Table 2.

Comparison of the characteristics of PCBD, CG and PGD. PCBD, persistent complex bereavement disorder; CG, complicated grief; PGD, prolonged grief disorder. Criterion B and C are the diagnostic criteria for PCBD. The grey colour shows common items across these criteria.

|

Other aspects of the diagnostic criteria for PCBD have been debated. Boelen & Prigerson [59] criticized the criteria of PCBD based on the inclusion of some new items such as ‘difficulty in positive reminiscing’, which were not included in the sets proposed for PGD [54] and CG [8], and that there was no evidence that the 12-month post-loss criterion was effective for distinguishing CG from normal grief. Many authors have considered the appropriateness of the diagnostic criteria for ICD-11 and revising the DSM-5 [55–58,60]. In a study of clinical and community samples, Cozza et al. [57] found that CG criteria showed higher accuracy than PGD and PCBD, which excluded non-clinical cases and identified more than 90% of clinical cases. Maciejewski et al. [58] compared the four proposed criteria for distorted grief, including PGD, PCBD, CG and PGD of the ICD-11 beta draft, among community samples. They reported PGD, PGD of ICD-11 and PCBD having a high consistency of diagnosis (0.80–0.84) and similar sensitivity (0.83–0.93) and specificity (0.95–0.98) [58]. They suggested that CG criteria differed from the others because CG had a moderate pairwise agreement with the other criteria (0.48–0.55) and had a high sensitivity (1.0) and moderate specificity (0.79) [58]. Maciejewski et al. [58] expressed concern that CG might identify a high rate of false-positive cases and pathologize normal grief. However, Reynolds et al. [56] argued that the sample used in Maciejewski et al.'s study [58] was biased towards non-clinical and elderly female subjects, and that CG criteria were superior to PGD for detecting clinical samples. Underlying the controversy about diagnostic criteria is a lack of consensus regarding the core concept and biological evidence of the pathology of grief.

6. Recent trends in CG treatment

Despite the lack of consensus regarding diagnostic criteria for CG, studies on treatment have made progress over the past decade. In pharmacotherapy, the focus is on the effectiveness of antidepressants. One study [48] reported that a tricyclic antidepressant (nortriptyline) was effective for depressive symptoms, but not for grief symptoms. Studies using other types of antidepressant, namely serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors including escitalopram [61,62] and paroxetine [63], showed a significant reduction in ICG scores in a before-and-after procedure without a control group. However, a randomized clinical trial to examine the efficacy of citalopram [47] found that it significantly improved depressive symptoms such as suicidal ideation, but was not effective for CG symptoms. At present, there is no evidence that antidepressants are effective for treating CG.

Stroebe et al. [64] conducted a systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial and psychological counselling at three stages including primary, secondary and tertiary preventive interventions. Primary interventions were effective for all bereaved individuals including those with higher levels of mental health problems before intervention. Secondary interventions for high-risk bereaved individuals were effective when associated with stringent risk criteria, showing the need for further differentiation within groups and tailoring intervention for subgroups. In the tertiary intervention for bereaved individuals with mental disorders, the specific individual treatments for CG were effective.

Wittouck et al. [65] reported a meta-analysis of the prevention and treatment of CG. They were unable to establish the effectiveness of a preventive intervention for CG; however, treatment interventions, especially cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) [46,51,66] focused on CG, could effectively reduce CG symptoms. In addition, it was reported that some randomized controlled trials of CBT focused on CG including the exposure components to death situations [47,67] were effective, with a large effect size. Shear [68] stated that imaginal revisiting—the name of the exposure strategy in their treatment—was intended to facilitate the ability to both think about death and set it aside. Boelen et al. [51] reported that the effect size of the exposure component in CBT for CG (0.94) was greater than the cognitive restriction component (0.44), and exposure appeared effective in terms of avoidant thoughts and behaviours. Bryant et al. [67] reported that CBT with exposure therapy was more effective for CG than CBT alone, and that the exposure component might promote emotional processing of memories of the death. Although the method of exposure component varies across treatment studies, it is commonly used to reduce avoidance of reminders and memories of the deceased, and to promote the acceptance of death and restriction of negative thoughts. The results of these treatment studies are considered to provide insights into the pathology of CG.

7. Conclusion

This article briefly reviewed progress in our understanding of pathological grief as typified by CG, the debate regarding new diagnostic criteria and recent trends in CG treatment. The loss of a loved one is inevitable, and the psychology of grief, especially pathological grief, has been increasingly intensively studied in recent years. In the 1990s, a type of pathological grief was studied; it was similar to CG, characterized by an extended period of acute grief and impaired physical, psychological and social functioning, and treatment measures were developed. Naming this condition as PCBD and including it as a psychiatric disorder in DSM-5 marked a milestone in CG research. The prevalence rate of CG is 2.4% [42] to 6.7% [43] among the general population; this means that many people in the world suffer from this condition for a long time, especially in disaster- and conflict-affected regions. Given the importance of developing effective and convenient treatment methods for these people, we need to reach a consensus on diagnostic criteria and continue to develop standardized assessment tools.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Competing interests

I declare that I have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP17H02645).

References

- 1.Bowlby J. 1982. Attachment and loss, Vol. 3 loss—sadness and depression. London, UK: Tavistock Institute of Human Relations. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freud S. 1957. Mourning and melancholia. In Standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud 14 (ed. and trans. J. Strachey), pp. 243–258. London, UK: Hogarth Press; (Originally published 1917.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W. 2008. Bereavement research: contemporary perspectives. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schutm H, Stroebe W), pp. 3–25. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon NM. 2013. Treating complicated grief. JAMA 310, 416–423. ( 10.1001/jama.2013.8614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lobb EA, Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM, Monterosso L, Halkett GK, Davies A. 2010. Predictors of complicated grief: a systematic review of empirical studies. Death Stud. 34, 673–698. ( 10.1080/07481187.2010.496686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindemann E. 1944. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am. J. Psychiatry 101, 141–148. ( 10.1176/ajp.101.2.141) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF III, Shear MK, Newsom JT, Jacobs S. 1996. Complicated grief as a disorder distinct from bereavement-related depression and anxiety: a replication study. Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 1484–1486. ( 10.1176/ajp.153.11.1484) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shear MK, et al. 2011. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety 28, 103–117. ( 10.1002/da.20780) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs S, Mazure C, Prigerson H. 2000. Diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Death Stud. 24, 185–199. ( 10.1080/074811800200531) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prigerson HG, Vanderwerker LC, Maciejewski PK, Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W. 2008. A case for inclusion of prolonged grief disorder in DSM-V. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 165–186. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. 2008. An attachment perspective on bereavement. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 87–112. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 13.King BJ. 2013. How animals grieve. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archer J. 2008. Theories of grief: past, present, and future perspectives. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 45–66. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkes CM. 1996. Bereavement: studies of grief in adult life, 3rd edn London, UK: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nesse MN. 2000. Is grief really maladaptive? [Book review: the nature of grief: the evolution and psychology of reactions to loss; John Archer, London: Routledge, 1999. 317 pp.]. Evol. Hum. Behav. 21, 59–61. ( 10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00019-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Attig T. 2001. Relearning the world: making and finding meaning. In Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss (ed. Neimeyer RA.), pp. 33–53. Washington, DC: The American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tedeschi RCJ. 1995. Trauma and transformation. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonanno GA. 2004. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? Am. Psychol. 59, 20–28. ( 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engel GL. 1961. Is grief a disease? A challenge for medical research. Psychosom. Med. 23, 18–22. ( 10.1097/00006842-196101000-00002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Worden JM. 2008. Grief counseling and grief therapy: a handbook for the mental health practitioner, 4th edn New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stroebe M, Schut H. 1999. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud. 23, 197–224. ( 10.1080/074811899201046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. 2007. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA 297, 716–723. ( 10.1001/jama.297.7.716) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland JM, Neimeyer RA. 2010. An examination of stage theory of grief among individuals bereaved by natural and violent causes: a meaning-oriented contribution. Omega 61, 103–120. ( 10.2190/OM.61.2.b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neimeyer RA. 2000. Lesson of loss: a guide to coping, pp. 541–558. Keystone Heights, FL: Psycho Educational Resources. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Fu F, Sha W, Chan CLW, Chow AYM. 2017. Mothers coping with bereavement in the 2008 China earthquake: a dual process model analysis. Omega. ( 10.1177/0030222817725181) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kübler-Ross E. 1969. On death and dying. New York, NY: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss RS. 2008. The nature and causes of grief. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 29–44. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field NP. 2008. Whether to relinquish or maintain a bond with the deceased. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 113–132. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foa EB, Kozak MJ. 1986. Emotional processing of fear: exposure to corrective information. Psychol. Bull. 99, 20–35. ( 10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.20) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson VE. 2010. Length of caregiving and well-being among older widowers: implications for the dual process model of bereavement. Omega 61, 333–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robben AC. 2014. Massive violent death and contested national mourning in post-authoritarian Chile and Argentina: a sociocultural application of the dual process model. Death Stud. 38, 335–345. ( 10.1080/07481187.2013.766653) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF III, Bierhals AJ, Newsom JT, Fasiczka A, Frank E, Doman J, Miller M. 1995. Inventory of complicated grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiat. Res. 59, 65–79. ( 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shar KM, Jackson CT, Essock SM, Donahue SA, Felton CJ. 2006. Screening for complicated grief among project liberty service recipients 18 months after September 11, 2001. Psychiatr. Serv. 57, 1291–1297. ( 10.1176/ps.2006.57.9.1291) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, Farver-Vestergaard I, O'Connor M. 2017. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 212, 138–149. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neria Y, et al. 2007. Prevalence and psychological correlates of complicated grief among bereaved adults 2.5–3.5 years after September 11th attacks. J. Traum. Stress 20, 251–262. ( 10.1002/jts.20223) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latham AE, Prigerson HG. 2004. Suicidality and bereavement: complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 34, 350–362. ( 10.1521/suli.34.4.350.53737) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF III, Shear MK, Day N, Beery LC, Newsom JT, Jacobs S. 1997. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. Am. J. Psychiatr. 154, 616–623. ( 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ott CH. 2003. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Stud. 27, 249–272. ( 10.1080/07481180302887) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverman GK, Jacobs SC, Kasl SV, Shear MK, Maciejewski PK, Noaghiul FS, Prigerson HG. 2000. Quality of life impairments associated with diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief. Psychol. Med. 30, 857–862. ( 10.1017/S0033291799002524) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. 2007. The influence of symptoms of prolonged grief disorder, depression, and anxiety on quality of life among bereaved adults: a prospective study. Eur. Arch. Psychiat. Clin. Neurosci. 257, 444–452. ( 10.1007/s00406-007-0744-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, Ito M, Kato M, Kim Y. 2010. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. J. Affect. Disord. 127, 352–358. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kersting A, Brahler E, Glaesmer H, Wagner B. 2011. Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. J. Affect. Disord. 131, 339–343. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakajima S, Shirai A, Maki S, Ishii Y, Nagamine M, Tatsuno B, Konishi S. 2009. Mental health of the families of crime victims and factors related to their recovery. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 111, 423–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simon NM, Shear KM, Thompson EH, Zalta AK, Perlman C, Reynolds CF, Frank E, Melhem NM, Silowash R. 2007. The prevalence and correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in individuals with complicated grief. Compr. Psychiatry 48, 395–399. ( 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.05.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF III. 2005. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293, 2601–2608. ( 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shear MK, Reynolds CF III, Simon NM, Zisook S, Wang Y, Mauro C, Duan N, Lebowitz B, Skritskaya N. 2016. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 685–694. ( 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0892) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasternak RE, Reynolds CF III, Schlernitzauer M, Hoch CC, Buysse DJ, Houck PR, Perel JM. 1991. Acute open-trial nortriptyline therapy of bereavement-related depression in late life. J. Clin. Psychiatry 52, 307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newson RS, Boelen PA, Hek K, Hofman A, Tiemeier H. 2011. The prevalence and characteristics of complicated grief in older adults. J. Affec. Disord. 132, 231–238. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Connor MF, Wellisch DK, Stanton AL, Eisenberger NI, Irwin MR, Lieberman MD. 2008. Craving love? Enduring grief activates brain's reward center. Neuroimage 42, 969–972. ( 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.256) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J. 2007. Treatment of complicated grief: a comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 75, 277–284. ( 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.277) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rubin SS, Malkinson R, Witztum E. 2008. Clinical aspects of a DSM complicated grief diagnosis: challenges, dilemmas, and opportunities. In Handbook of bereavement research and practice: advances in theory and intervention (eds Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Schut H, Stroebe W), pp. 187–206. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johnson JG, First MB, Block S, Vanderwerker LC, Zivin K, Zhang B, Prigerson HG. 2009. Stigmatization and receptivity to mental health services among recently bereaved adults. Death Stud. 33, 691–711. ( 10.1080/07481180903070392) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prigerson HG, et al. 2009. Prolonged grief disorder: psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 6, e1000121 ( 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mauro C, et al. 2017. Performance characteristics and clinical utility of diagnostic criteria proposals in bereaved treatment-seeking patients. Psychol. Med. 47, 608–615. ( 10.1017/S0033291716002749) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reynolds CF III, Cozza SJ, Shear MK. 2017. Clinically relevant diagnostic criteria for a persistent impairing grief disorder: putting patients first. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 433–434. ( 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0290) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cozza SJ, et al. 2016. Performance of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder criteria in a community sample of bereaved military family members. Am. J. Psychiatry 173, 919–929. ( 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111442) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maciejewski PK, Maercker A, Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. 2016. ‘Prolonged grief disorder’ and ‘persistent complex bereavement disorder’, but not ‘complicated grief’, are one and the same diagnostic entity: an analysis of data from the Yale Bereavement Study. World Psychiatry 15, 266–275. ( 10.1002/wps.20348) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. 2012. Commentary on the inclusion of persistent complex bereavement-related disorder in DSM-5. Death Stud. 36, 771–794. ( 10.1080/07481187.2012.706982) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. 2017. Rebuilding consensus on valid criteria for disordered grief. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 435–436. ( 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0293) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hensley PL, Slonimski CK, Uhlenhuth EH, Clayton PJ. 2009. Escitalopram: an open-label study of bereavement-related depression and grief. J. Affect. Disord. 113, 142–149. ( 10.1016/j.jad.2008.05.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simon NM, Thompson EH, Pollack MH, Shear MK. 2007. Complicated grief: a case series using escitalopram. Am. J. Psychiatry 164, 1760–1761. ( 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07050800) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zygmont M, Prigerson HG, Houck PR, Miller MD, Shear MK, Jacobs S, Reynolds CF III. 1998. A post hoc comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline for symptoms of traumatic grief. J. Clin. Psychiatry 59, 241–245. ( 10.4088/JCP.v59n0507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. 2007. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 370, 1960–1973. ( 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wittouck C, Van Autreve S, De Jaegere E, Portzky G, van Heeringen K. 2011. The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 69–78. ( 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wagner B, Knaevelsrud C, Maercker A. 2006. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. Death Stud. 30, 429–453. ( 10.1080/07481180600614385) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bryant RA, Kenny L, Joscelyne A, Rawson N, Maccallum F, Cahill C, Hopwood S, Aderka I, Nickerson A. 2014. Treating prolonged grief disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 1332–1339. ( 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1600) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shear MK. 2010. Complicated grief treatment: the theory, practice and outcomes. Bereave Care 29, 10–14. ( 10.1080/02682621.2010.522373) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.