WSL5 is crucial for the splicing of the chloroplast genes rpl2 and rps12 under cold stress, and affects the retrograde signaling from plastids to the nucleus.

Keywords: Chloroplast development, cold stress, Oryza sativa, ribosome biogenesis, RNA-seq, RNA splicing

Abstract

Chloroplasts play an essential role in plant growth and development, and cold conditions affect chloroplast development. Although many genes or regulators involved in chloroplast biogenesis and development have been isolated and characterized, many other components affecting chloroplast biogenesis under cold conditions have not been characterized. Here, we report the functional characterization of a white stripe leaf 5 (wsl5) mutant in rice. The mutant develops white-striped leaves during early leaf development and is albinic when planted under cold stress. Genetic and molecular analysis revealed that WSL5 encodes a novel chloroplast-targeted pentatricopeptide repeat protein. RNA sequencing analysis showed that expression of nuclear-encoded photosynthetic genes in the mutant was significantly repressed, and expression of many chloroplast-encoded genes was also significantly changed. Notably, the wsl5 mutation causes defects in editing of rpl2 and atpA, and splicing of rpl2 and rps12. wsl5 was impaired in chloroplast ribosome biogenesis under cold stress. We propose that the WSL5 allele is required for normal chloroplast development in maintaining retrograde signaling from plastids to the nucleus under cold stress.

Introduction

Cold is an important environmental factor affecting chloroplast development and growth in juvenile plants. Sudden low temperature events that often occur during early seedling development in spring can directly affect chlorophyll development (Kusumi and Iba, 2014). Rice seedlings are susceptible to cold stress, with an impact that ultimately affects grain yield (Liu et al., 2013). Therefore, cold stress is a common problem that affects grain production, and rice varieties with increased cold tolerance are preferred (Zhao et al., 2017). Many studies have suggested that plants can regulate early chloroplast development under cold stress. The chlorophyll content in young leaves of a virescent mutant was low, but gradually increased to normal levels as they grew (Yoo et al., 2009). Temperature-sensitive virescent mutants were used to study mechanisms regulating chloroplast development in seedlings under cold stress, and many genes were identified (e.g. V3, St1, OsV4, TCD9, and TSV) (Yoo et al., 2009; Gong et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2017). However, the mechanisms of chloroplast development in rice seedlings under cold stress remain poorly understood.

Chloroplasts are essential for photosynthesis and have crucial roles in plant development and growth by fixation of CO2 and biosynthesis of carbon skeletons, as well as other physiological processes (Jarvis and López-Juez, 2013). Formation of a photosynthetically active chloroplast from a proplastid is controlled by both nuclear-encoded polymerase (NEP) and plastid-encoded polymerase (PEP) genes (Yu et al., 2014). NEP is a single protein that is responsible for the transcription of genes encoding PEP subunits, ribosomal proteins, and other plastidic ‘housekeeping’ proteins (Liere et al., 2011). PEP, on the other hand, is a large, dynamic complex with many transiently attached peripheral subunits (Yu et al., 2014).

Chloroplast RNAs need to be processed to become functional rRNAs and mRNAs. Many of the processing factors for RNA cleavage, splicing, editing, and stability are RNA-binding proteins (Tillich and Krause, 2010). All are encoded by the nuclear genome. Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins are a family of RNA-binding proteins that usually carry out specific RNA processing in chloroplasts (Stern et al., 2010; Shikanai and Fujii, 2013). PPR proteins are defined by tandem arrays of a degenerate 35 amino acid repeat (PPR motif). In higher plants, the PPR family comprises many members, with 450 in Arabidopsis and 655 in rice (O’Toole et al., 2008). The functions of PPR proteins are well characterized (Stern et al., 2010; Shikanai and Fujii, 2013). Chloroplast-targeted PPR proteins were characterized as being involved in regulating RNA splicing, RNA editing, RNA stability, and RNA translation during plant development and growth (Yu et al., 2009; Ichinose et al., 2012). Several PPR genes in rice, such as YSA, OsV4, WSL, ALS3, OspTAC2, and WSL4, were reported to function in RNA editing, RNA splicing and chloroplast development (Su et al., 2012; Gong et al., 2014; Tan et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2015; D. Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). The rice PPR mutant ysa develops albinic leaves before the three-leaf stage, but the plants gradually turn green and recover to normal green at the six-leaf stage (Su et al., 2012). WSL encodes a PPR protein that is targeted to the chloroplast and plays an essential role in the splicing of rpl2 (Tan et al., 2014). The P-family PPR mutant wsl4, which exhibits white-striped leaves before the five-leaf stage, has defective chloroplast RNA group II intron splicing (Wang et al., 2017). However, the functions, substrates, and regulatory mechanisms of many PPR proteins in rice remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we isolated and characterized the rice mutant wsl5 that develops white-striped leaves at the early seedling stage. wsl5 is albinic under low temperatures. WSL5 encodes a P-family PPR protein containing an RNA recognition motif (RRM) at its N-terminus and 15 PPR motifs at its C-terminus. WSL5 locates to the chloroplast and is essential for chloroplast ribosome biogenesis under cold stress. We showed that RNA editing sites of rpl2 and atpA were not edited, and plastid-encoded genes rpl2 and rps12 were not efficiently spliced in the wsl5 mutant. Abnormal splicing of rpl2 and rps12 may lead to chloroplast failure to form functional ribosomes, which blocks retrograde signaling from chloroplasts to the nucleus. Our results provide novel insights into the function of WSL5 in regulating rice chloroplast development under cold stress.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

The wsl5 mutant was isolated from an ethylmethane sulfonate (EMS) mutant pool of indica cultivar Nanjing 11. Seedlings were grown in a growth chamber under 16 h of light/8 h of darkness at constant temperatures of 20, 25, and 30 °C. The third leaves at ~10 d post-planting were used for nearly all analyses. To map the WSL5 locus, we constructed an F2 population derived from a cross of the wsl5 mutant and Dongjin (japonica).

Pigment determination and TEM

Wild-type and wsl5 mutant seedlings were grown in the field. Fresh leaves were collected and used to determine chlorophyll contents using a spectrophotometer according to the method of Arnon (1949). Briefly, 0.2 g of leaf tissue was collected, marinated in 5 ml of 95% ethanol, and held for 48 h in darkness. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation and were analyzed with a DU 800 UV/Vis Spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter) at 665, 649, and 470 nm, respectively.

TEM was performed according to the method of Y. Wang et al. (2016). Briefly, fresh leaves were collected and cut into small pieces, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a phosphate buffer at 4 °C for 4 h, further fixed in 1% OsO4, stained with uranyl acetate, dehydrated in an ethanol series, and finally embedded in Spurr’s medium prior to ultrathin sectioning. The samples were observed using a Hitachi H-7650 transmission electron microscope.

Map-based cloning and complementation of WSL5

Genetic analysis was performed using an F2 population (wsl5/Nanjing 11); 654 plants with the recessive mutant phenotype were used for genetic mapping. New simple sequence repeat (SSR)/Indel markers were developed based on the Nipponbare (japonica) and 93-11 (indica) genome sequences (http://www.gramene.org/). The WSL5 locus was narrowed to a 180 kb region between markers Y18 and Y47 on the long arm of chromosome 4 (see Table S2 available at the Dryad Digital Repository, http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.59185).

For complementation of the wsl5 mutation, a 2706 bp wild-type coding sequence fragment and an ~2 kb upstream sequence were amplified from variety Nanjing 11. They were cloned into the binary vector pCAMBIA1390 to generate the vector pCAMBIA1390-WSL5. This vector was introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105, which was then used to infect wsl5 mutant calli.

Sequence analysis

Gene prediction and structure analysis were performed using the GRAMENE database (www.gramene.org/). Homologous sequences of WSL5 were identified using the Blastp search program of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Multiple sequence alignments were conducted with DNAMAN.

Subcellular localization of WSL5 protein

For subcellular localization of WSL5 protein in rice, the coding sequence of WSL5 was amplified and inserted into the pAN580 vector. The cDNA fragments were PCR-amplified using primer pairs shown in Table S2 at Dryad. Transient expression constructs were separately transformed into rice protoplasts and incubated in darkness at 28 °C for 16 h before examination (Chen et al., 2006). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence was observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 780).

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNA prep pure plant kit (TIANGEN, Beijing). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers (TaKaRa) for chloroplast-encoded genes and oligo(dT)18 (TaKaRa) for nuclear-encoded genes, and reverse transcribed using Prime scriptase (TaKaRa). RT-PCR was performed in three biological repeats using an ABI 7500 real-time PCR system with SYBR Green Mix. Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Table S2 at Dryad. The rice Ubiquitin gene was used as an internal control.

RNA analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 10-day-old seedlings of the wild type and wsl5 grown in C30 and C20 conditions using an RNA prep pure plant kit. RNA samples were diluted to 10 ng m–1 and analyzed by an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. The RNA 6000 Nano Total RNA Analysis Kit (Agilent) was used for analysis.

RNA editing sites and RNA splicing analysis

Specific cDNA fragments were generated by RT-PCR amplification following established protocols (Takenaka and Brennicke, 2007). The cDNA sequences were compared to identify C to T changes resulting from RNA editing. For RNA splicing analysis, chloroplast genes with at least one intron were selected and amplified using RT-PCR with primers flanking the introns. The primers used for RNA editing and splicing analysis were obtained as reported previously (Tan et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017).

Protein extraction, SDS–PAGE, and western blotting

Leaf material was homogenized in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 0.15 M NaCl, 2% SDS, 0.01% 2-mercaptoethanol). Sample amounts were standardized by fresh weight. The protein samples were separated by 10% SDS–PAGE. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore) and incubated with specific antibodies. Signals were detected using an ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Kit (Thermo) and visualized by an imaging system (ChemiDocTMX- RS; Bio-Rad).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

The coding sequences of five rice multiple organellar RNA editing factors (MORFs) were amplified with primers listed in Zhang et al. (2017). MORFs and WSL5 were cloned into the pGAD-T7 or pGBK-T7 vectors, respectively. Yeast two-hybrid analysis was performed using the Clontech (www.clontech.com) two-hybrid system, following the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from leaves of 10-day-old wild-type and wsl5 seedlings grown at different temperatures. mRNA was enriched from total RNA using oligo(dT) primers and Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kits for chloroplast-encoded genes. cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers. The library was constructed and sequenced using an Illumina Hisequation 2000 (TGS, Shenzhen). Totals of 45 million reads of genes from the wild type and 42 million from wsl5 were obtained. The significance of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) was determined by using |log2 (fold change)|>1 and q-values <0.05. Gene Ontology (http://www.geneontology.org/) analyses were performed referring to GOseq (Young et al., 2010). Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database (Kanehisa et al., 2008).

Results

Characterization of the wsl5 mutant

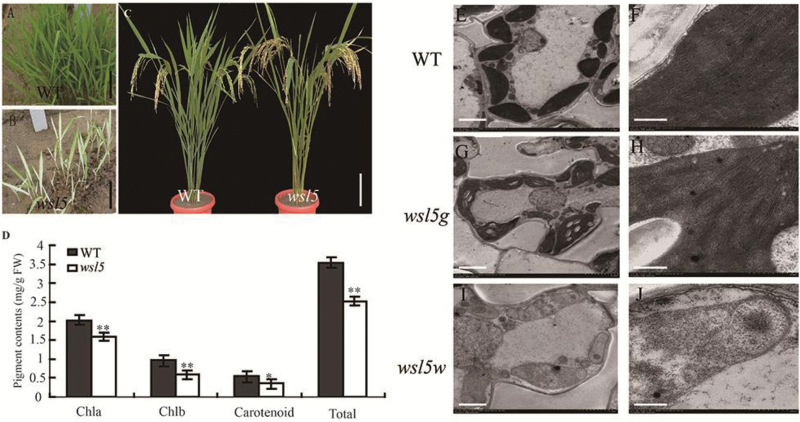

To identify genetic factors regulating chloroplast development in rice, we used the wsl5 mutant obtained in an EMS mutant pool of Nanjing 11 (indica). Seedlings of wsl5 exhibited a white-striped leaf phenotype up to the four-leaf stage under field conditions (Fig. 1A, B). Normal green leaves occurred thereafter. Chlorophyll (Chl a and Chl b) and carotenoid contents were reduced in the wsl5 mutant seedlings before the five-leaf stage, but were subsequently similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 1D; Fig. S1 at Dryad). The major agronomic traits of the wsl5 mutant at maturity, including plant height and grain size, were indistinguishable from those of wild-type plants (Fig. 1C; Table S1 at Dryad). To examine whether the color deficiency was accompanied by ultrastructural changes in chloroplasts, we compared the ultrastructure of chloroplasts in white and green sectors of wsl5 mutant leaves and normal wild-type leaves by TEM. Cells in wild-type leaves and green sectors in leaves of wsl5 had normal chloroplasts displaying structured thylakoid membranes composed of grana connected by stroma lamellae (Fig. 1E, H). However, the white sectors of wsl5 had abnormal chloroplasts (Fig. 1I, J). The results suggested that WSL5 had a role in chloroplast development in juvenile plants.

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of the wsl5 mutant. (A, B) Phenotypes of wild-type (WT) and wsl5 mutant seedlings in the field 20 d after seeding. (C) Phenotypes of WT (left) and wsl5 (right) plants at maturity. (D) Leaf pigment contents of field-grown WT and wsl5 seedlings at 20 d after seeding. (E, F) Mesophyll cells in WT plants showing normal, well-ordered chloroplasts. (G, H) Chloroplasts from green sectors of wsl5 seedlings were indistinguishable from those of the WT. (I, J) Cells from white sectors of the mutants displayed abnormalities, including vacuolated plastids and lack of organized thylakoid membranes. Scale bar=1 cm in (A, B), 10 cm in (C), 1 μm in (E, G, I), 500 nm in (F, H, J) (Student’s t-test, **P<0.01, *P<0.05).

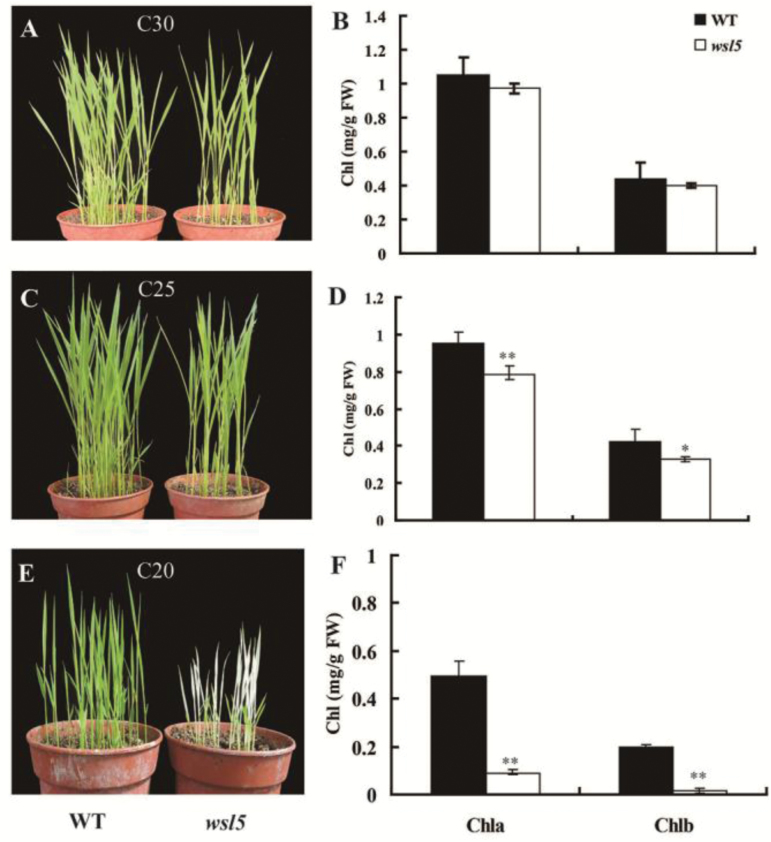

The wsl5 phenotype was temperature sensitive

To verify whether the wsl5 mutant was affected by temperature, wsl5 and wild-type seedlings were grown in growth chambers under constant temperatures of 20, 25, and 30 °C (C20, C25, and C30). Leaves of the wsl5 mutant were albinic at 20 °C (Fig. 2E) and the plants died. Chlorophyll was not detectable in the leaves (Fig. 2F). At 25 °C, the wsl5 mutant developed leaves with white stripes and reduced chlorophyll content (Fig. 2C, D). At 30 °C, wsl5 exhibited almost the same phenotype as the wild type (Fig. 2A) and contained similar pigment contents (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that the lack of WSL5 protein at 20 °C resulted in the observed damage.

Fig. 2.

The wsl5 phenotype is temperature sensitive. (A, C, E) Phenotypes of wild-type (WT) and wsl5 seedlings produced at different constant temperatures. C20, C25, and C30, refer to 20, 25, and 30 °C, respectively. (B, D, F) Leaf pigment contents of WT and wsl5 seedlings grown at different temperatures (Student’s t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01).

We also examined the ultrastructure of chloroplasts in mesophyll cells of wild-type and wsl5 plants. At 30 °C, all the wild-type and wsl5 plants displayed normal chloroplasts with well-developed lamellar structures and normally stacked grana and thylakoid membranes (Fig. S2A–D at Dryad). At 20 °C, the wild type developed large starch grains and chloroplasts with normal thylakoids (Fig. S2E, F at Dryad), whereas leaf cells from albinic sectors in wsl5 had no chloroplasts (Fig. S2G, H at Dryad). The results indicated that the lack of WSL5 protein at 20 °C resulted in the observed damage.

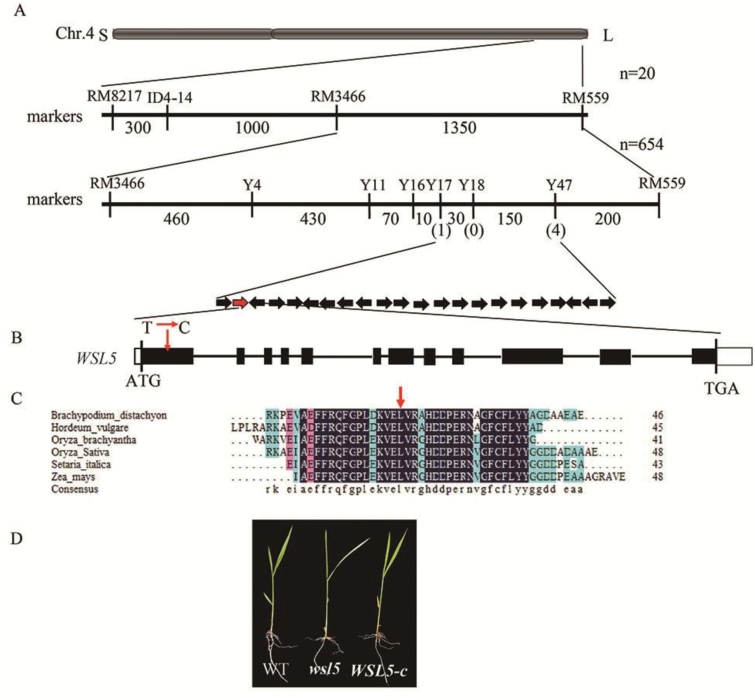

Map-based cloning of the WSL5 allele

Genetic analysis showed that the white stripe phenotype of the wsl5 mutant was controlled by a single recessive nuclear locus. To identify the WSL5 locus, 20 F2 individuals with the mutant phenotype derived from a cross between wsl5 and Dongjin (japonica) were used. The WSL5 locus was located to a 2.65 Mb region between markers RM8217 and RM559 on the long arm of chromosome 4. It was further delimited to a 180 kb region between markers Y17 and Y47 using 654 F2 plants with the mutant phenotype. Twenty-two ORFs were predicted in the region from published data (http://www.gramene.org/;Fig. 3A). Sequence analysis of the region showed that only one ORF encoding a PPR protein differed between the wild type and wsl5 (Fig. 3B). A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; T to C) located in the conserved region caused a leucine to proline amino acid substitution in the mutant (Fig. 3B, C).

Fig. 3.

Map-based cloning of the WSL5 allele. (A) The WSL5 locus was mapped to a 180 kb region between markers Y17 and Y47 on chromosome 4L. Black arrows represent 22 putative genes in this region; the candidate gene WSL5 (Os04g0684500) is shown by a red arrow. (B) ATG and TGA represent the start and stop codons, respectively. Black boxes indicate the exons, and the white boxes indicate the 3'- and 5'-UTRs. An SNP in the first exon in WSL5 causes a leucine to proline amino acid substitution. (C) Alignment of amino acid sequences with highest identity to the WSL5 protein. The red arrow indicates an amino acid change. (D) Complementation of wsl5 by transformation.

To confirm that mutation of WSL5 was responsible for the mutant phenotype, the WSL5 coding region driven by the UBQ promoter was transformed into calli derived from wsl5. Twenty-eight of 45 transgenic lines resistant to hygromycin and harboring the transgene displayed the wild-type phenotype (Fig. 3D). These results confirmed that Os04g0684500 was WSL5.

WSL5 encodes a PPR protein

Sequence analysis showed that WSL5 comprised 12 exons and 11 introns. The single base substitution in wsl5 was located in the first exon (Fig. 3B). A database search with Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/search) revealed that WSL5, which belongs to the P family, contained an RRM at its N-terminus and 15 PPR motifs at the C-terminus. The substituted amino acid (leucine) was highly conserved in the RRM of homologous proteins (Fig. 3C), suggesting an obligate role for this site in functional integrity of WSL5 protein. WSL5 shared a high degree of sequence similarity with maize PPR4 (84% identity) and Arabidopsis thaliana At5g04810 (59% identity) (Fig. S3 at Dryad). Together, these results indicated that WSL5 encodes a novel PPR protein.

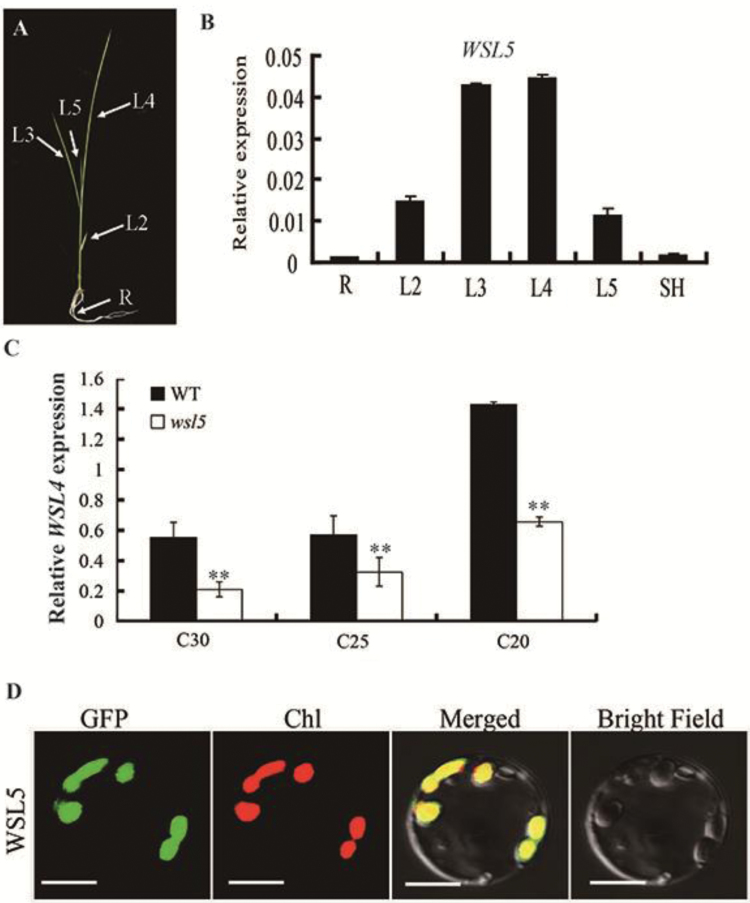

Expression pattern and subcellular localization of WSL5

Using the Rice eFP Browser (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efprice/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi), we found that WSL5 was expressed in all tissues, especially in young leaves. To verify these data, we examined the expression levels of WSL5 in different organs of the wild type by qRT-PCR (Fig. 4A, B). The WSL5 transcript was preferentially expressed in young leaves (Fig. 4B), suggesting that WSL5 had an important role in chloroplast development in young seedlings. The WSL5 transcript was more abundant in plants grown at 20 °C than at 30 °C, indicating that WSL5 was induced by low temperature. Thus plants might express WSL5 abundantly to regulate chloroplast development under cold stress (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Expression pattern analysis and subcellular localization of WSL5. (A) Schematic of a rice seedling with a fully expanded fourth leaf. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of WSL5 expression in roots, stems, L2, L3, L4, L5, and sheaths of the wild type (WT). (C) qRT-PCR analyses of the WSL5 transcript in WT and wsl5 mutant seedlings grown in a growth chamber with a 12 h photoperiod at 30, 25, and 20 °C. (D) Localization of WSL5 protein in rice protoplasts. Green fluorescence shows GFP, red fluorescence shows chloroplast autofluorescence, and yellow indicates the two types of fluorescence merged. Error bars represent the SD from three independent experiments (Student’s t-test, **P<0.01).

To examine the actual subcellular localization of WSL5, a Cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S-driven construct with a WSL5–GFP fusion protein was generated using the pAN580 vector and transiently expressed in rice protoplasts. Green fluorescent signals of WSL5–GFP co-localized with the autofluorescent signals of chlorophyll (Fig. 4D), suggesting that WSL5 localized to chloroplasts. These results, together with chloroplast localization and the observed wsl5 phenotype, supported the notion that WSL5 plays an important role in regulating chloroplast development in rice seedlings.

Expression of photosynthesis-related genes is down-regulated in wsl5

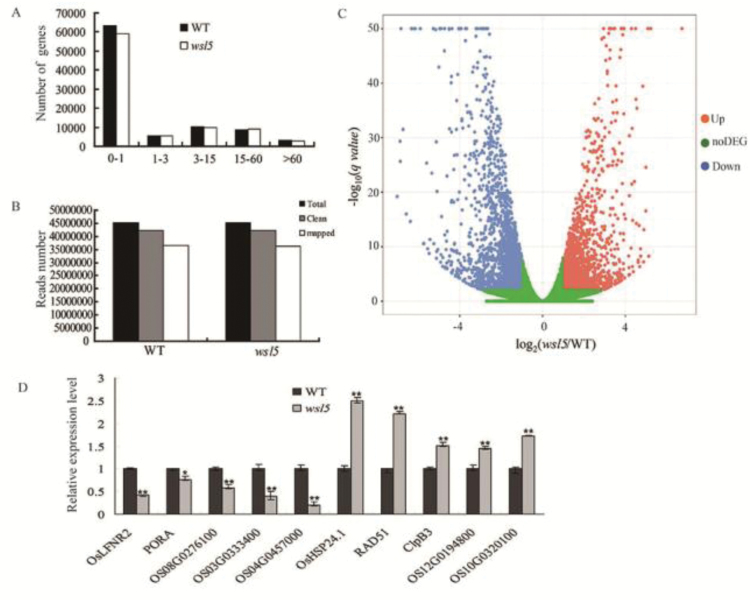

RNA-seq was performed to analyze the effect of the wsl5 mutation on gene expression. A total of 42 million clean reads were obtained from the wild type and wsl5 grown in C25 conditions. Compared with the wild type, there were 1699 up-regulated genes and 1999 down-regulated genes in wsl5 (Fig. 5A–C; Dataset S1 at Dryad). We randomly selected five down-regulated and five up-regulated genes to verify the results of RNA-seq. The qRT-PCR results were consistent with those from RNA-seq (Fig. 5D). GO and KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that the expression of genes encoding photosynthesis, light reaction, PSI and PSII, chloroplast thylakoid, ATP synthase, and carbon fixation were reduced in wsl5 (Figs S5, S6 at Dryad). Also, some chlorophyll synthesis genes, including HEMA, YGL8, PORA, CHLH, and CRD1, were significantly reduced, which was verified using RT-PCR (Fig. S7 at Dryad).

Fig. 5.

RNA-seq analysis of wild-type (WT) and wsl5 seedlings grown in C25 conditions. mRNA was enriched using oligo(dT) primers from total RNA isolated from 10-day-old (third leaf) seedlings of the WT and wsl5 using oligo(dT). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers. The library was then constructed and sequenced using an Illumina HiSEquation 2000. (A) Frequencies of detected genes sorted according to expression levels. (B) Read numbers of WT and wsl5 sequences. (C) Volcano plot showing the overall alterations in gene expression in the wild type and wsl5. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of genes differentially expressed in RNA-seq. Five up-regulated and five down-regulated genes were tested. Error bars represent the SD from three independent experiments (Student’s t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01).

wsl5 mutants have global defects in plastidic gene expression

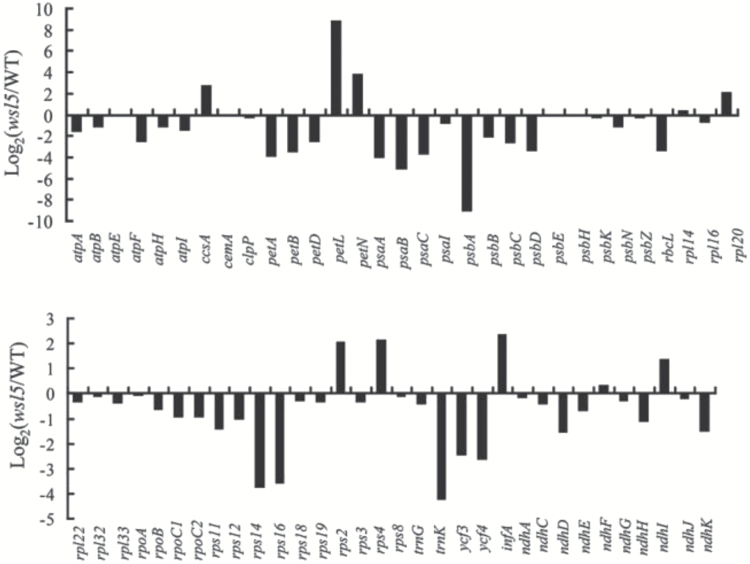

To investigate whether the WSL5 mutation affects transcription by PEP and NEP, we examined the transcript abundance of various plastidic genes in the wsl5 mutant grown in C25 conditions by RNA-seq. The expression of many plastidic genes differed between wsl5 and the wild type (Fig. 6). Compared with the wild type, the expression of plastidic genes that are transcribed by PEP, including psbA, psbB, psbD, petB, ndhA, and rbcL, was strongly reduced in the wsl5 mutant. In addition, the transcript levels of plastidic genes, including ribosomal protein L32 (rpl32), rpl14, rps2, rps4, and rpoA, which are transcribed by NEP, were increased or unchanged in the mutant (Fig. 6). These results indicated that the wsl5 mutation influenced the optimal expression of plastidic genes in rice seedlings.

Fig. 6.

Differential expression of plastid-encoded genes in the wild type (WT) and wsl5 grown in C25 conditions. mRNA was enriched from total RNA using Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kits for chloroplast-encoded genes from 10-day-old seedlings of the WT and wsl5. mRNA was fragmented and reverse-transcribed using random hexamer primers. The library was then constructed and sequenced using an Illumina HiSEquation 2000. The graph shows the log2 ratio of transcript levels in the wsl5 mutant compared with the WT.

Analysis of transcripts and proteins of genes associated with chloroplast biogenesis in wsl5

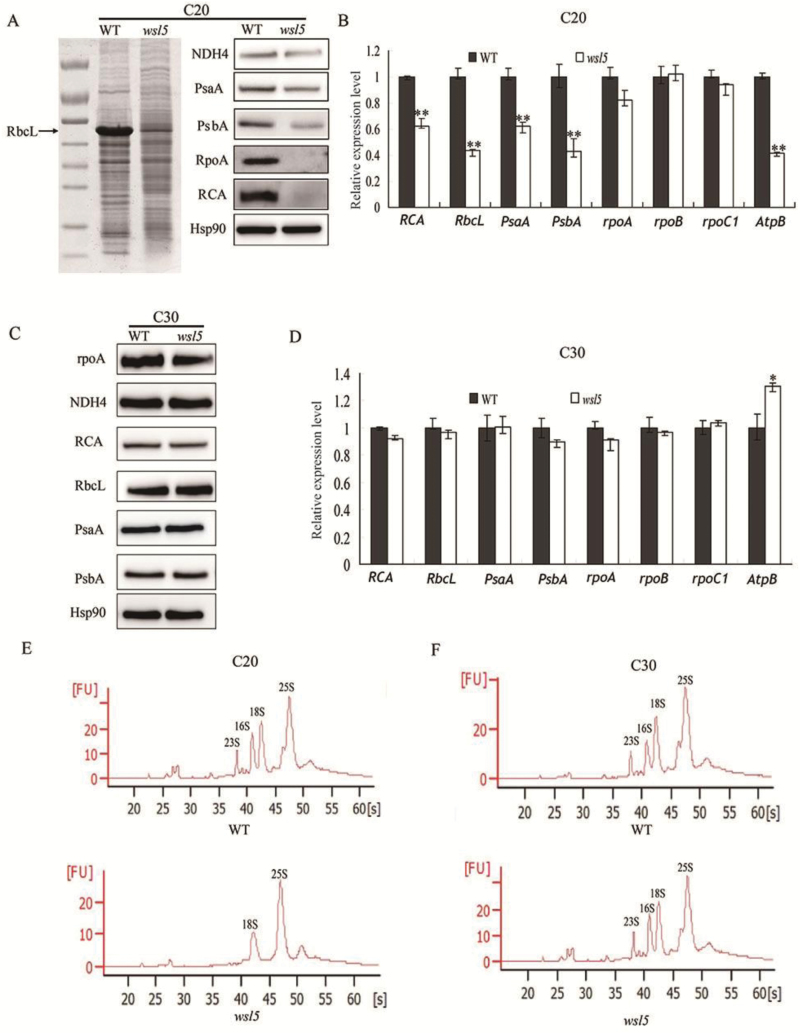

Since WSL5 was located in chloroplasts, we tested the accumulation of chloroplast proteins in wsl5 and the wild type using western blot analysis under C20 and C30 conditons. Under C20 conditions, the protein levels of the large subunit of Rubisco (RbcL) and Rubisco activase (RCA) were much lower in wsl5 (Fig. 7A). Other plastidic proteins including NADH dehydrogenase subunit 4, A1 of PSI, D1 of PSII, and the α-subunit of RNA polymerase were tested. The results showed that the levels of plastid-encoded proteins were significantly decreased in wsl5 (Fig. 7A). Plastidic genes can be classified into three types. Class I genes are predominantly transcribed by PEP, class II genes are transcribed by both NEP and PEP, and class III genes are exclusively transcribed by NEP. qRT-PCR results suggested that the expression levels of class I genes RbcL, psbA, and psaA were strikingly reduced, whereas expression of the class III genes rpoA and rpoC1, and class II gene AtpB, was unchanged (Fig. 7B). When grown in C30 conditions, the transcripts and proteins of all genes in the mutant and the wild type showed very slight differences in expression pattern (Fig. 7C, D). These results indicated that WSL5 was required for PEP activity under cold stress.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of accumulation of transcripts and proteins of representative genes associated with chloroplast biogenesis in wild-type (WT) and wsl5 seedlings. (A, C) Western blot analysis of chloroplast proteins and RCA in WT and wsl5 seedlings at the third-leaf stage at C20 (A) and C30 (C). Hsp90 was used as an internal control. (B, D) qRT-PCR analysis of relative expression levels of plastid-encoded genes in the WT and wsl5 at the third-leaf stage under (B) C20 or (D) C30. Error bars represent the SD from three independent experiments. (E, F) rRNA analysis using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. RNA was isolated from 10-day-old WT and wsl5 seedlings grown at C30 and C20 (Student’s t-test, **P<0.01).

The chloroplast ribosome consists of a 50S large subunit and a 30S small subunit. Both subunits are comprised of rRNAs (23S, 16S, 5S, and 4.5S) and ribosomal proteins. We analyzed the composition and content of rRNAs using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer under C20 and C30 conditions. Both 23S and 16S rRNAs were decreased in wsl5 seedlings under cold stress, but there was no difference relative to the wild type under C30 conditions (Fig. 7E, F). These results clearly indicated severe defects in plastidic ribosome biogenesis in the wsl5 mutant seedlings grown under low temperature conditions.

The wsl5 mutant is defective in RNA editing and splicing of chloroplast group II introns

PPR proteins are required for RNA editing, splicing, stability, maturation, and translation (Tan et al., 2014; Hammani et al., 2016). Since WSL5 belongs to the P group, it was probably involved in transcript processing activities. First, we determined whether loss of WSL5 function affected editing at 21 identified RNA editing sites in chloroplast RNA (Corneille et al., 2000). The results showed that the editing efficiencies of rpl2 at C1 and atpA at C1148 were significantly decreased in the wsl5 mutant compared with the wild type (Fig. S8 at Dryad) whereas the other nine genes and corresponding 19 editing sites were normally edited in the wsl5 mutant. We then analyzed the editing efficiencies of rpl2 at C1 and atpA at C1148 in complemented transgenic plants. As expected, the editing efficiencies of rpl2 at C1 and atpA at C1148 were markedly improved in complemented plants (Fig. S8 at Dryad). These data supported the contention that the mutation in WSL5 affected the editing efficiency of rpl2 at C1 and atpA at C1148.

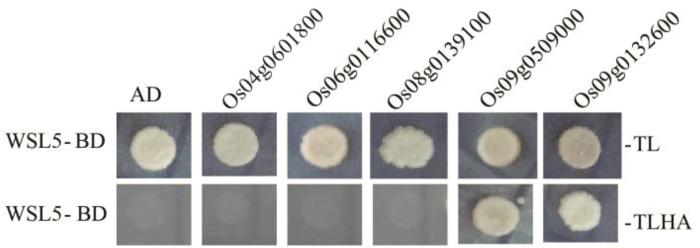

In A. thaliana, MORF proteins were implicated in RNA editing and provided a link between PPR proteins and proteins contributing to enzymatic activity (Takenaka et al., 2012). Based on A. thaliana MORF protein families (Zehrmann et al., 2015), we examined the potential interactions between rice MORF proteins and WSL5 by yeast two-hybrid analysis. The results showed that Os09g0509000 and Os09g0132600, both belonging to the A. thaliana MORF8 branch (Zhang et al. 2017), strongly interacted with WSL5 protein in yeast (Fig. 8). In contrast, Os04g0601800, Os06g0116600, and Os08g0139100 did not interact with WSL5 (Fig. 8). These results suggested that WSL5 may participate in RNA editing by interacting with OsMORF8s.

Fig. 8.

Yeast two-hybrid assay of WSL5 and MORF families. WSL5 was fused to the pGBKT7 vector (WSL5-BD). MORF protein was fused to the pGADT7 vector. LT, control medium (SD–Leu/–Trp); LTHA, selective medium (SD–Leu/–Trp/–His/–Ade). Empty pGBKT7 and pGAD-T7 vectors served as negative controls.

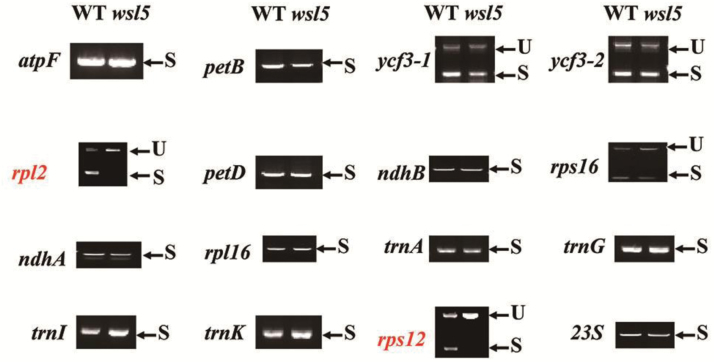

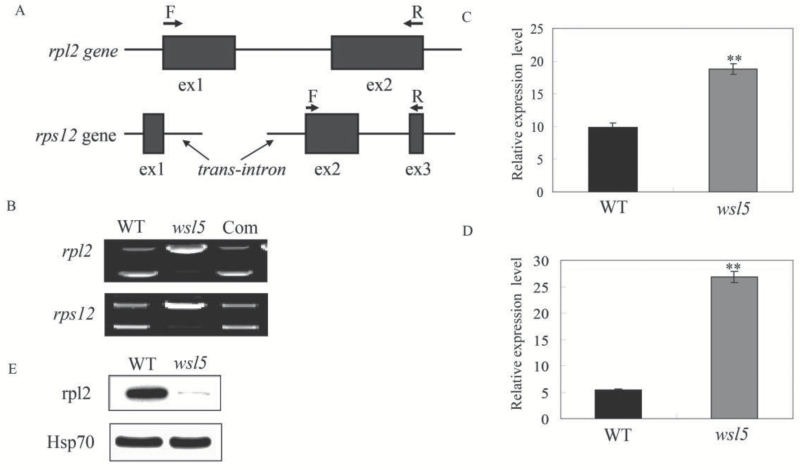

We tested whether WSL5 is involved in RNA splicing of chloroplast genes. The rice chloroplast genome contains 18 introns (17 group II introns and one group I intron) (Kaminaka et al., 1999). We amplified all chloroplast genes with at least one intron by RT-PCR using primers flanking the introns and compared the lengths of the amplified products between the wild type and the wsl5 mutant. Chloroplast transcripts rpl2 and rps12-2 were spliced at very low efficiency in wsl5 compared with the wild type (Figs 9, 10; Fig S9 at Dryad). To gain insight into the effects of the impaired splicing of rpl2 and rps12-2 on post-processing, we performed qRT-PCR and western blotting to examine the expression of rpl2 and rps12 in wsl5 at the RNA and protein levels. The rpl2 and rps12 transcript abundances were high in the mutant compared with the wild type (Fig. 10C, D), although the rpl2 protein was at a low level in the mutant compared with the wild type (Fig. 10E). Thus, the low splicing efficiency of rpl2 and rps12-2 resulted in aberrant transcript accumulation and reduced levels of rpl2 protein in the wsl5 mutant.

Fig. 9.

Splicing analysis of chloroplast transcripts in the wild type (WT) and wsl5. Gene transcripts are labeled on the left. Spliced (S) and unspliced (U) transcripts are shown on the right. RNA was extracted from WT and wsl5 seedlings.

Fig. 10.

Splicing analysis of two chloroplast group II introns in the wild type (WT) and wsl5. (A) Sketch map of rpl2 and rps12 transcripts. (B) RT-PCR analysis of rpl2 and rps12 transcripts in the WT and wsl5. (C, D) qRT-PCR analysis of rpl2 and rps12 transcripts in WT and wsl5 seedlings. (E) Western blot analysis of the rpl2 protein. Data are means ±SD of three repeats. Student’s t-test: **P<0.01.

Differentially expressed gene analysis in wsl5 and the wild type under cold stress and normal conditions

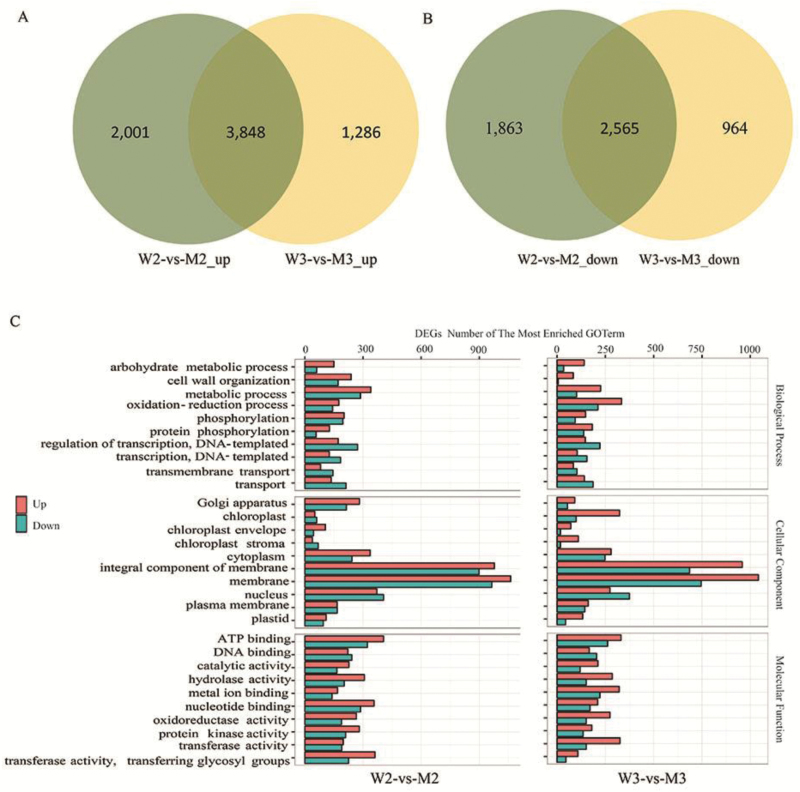

To investigate why phenotypic variagation in the wsl5 mutant depends on temperature, we carried out differential gene expression analysis in wsl5 and wild-type seedlings grown in growth cabinets at C20 and C30 by RNA-seq. mRNA was purified from total RNA isolated from the third leaves using poly(T) oligo-attached magnetic beads; 6491 overlapping genes were up- or down-regulated between the two temperature treatments (Fig. 11A, B; Dataset S2 at Dryad). GO analysis indicated that the expression of genes involved in metabolic processes, oxidation–reduction processes, photosynthesis, light reaction, PSI and PSII, chloroplast thylakoid, ATP synthase, and carbon fixation were strongly reduced in the wsl5 mutant at C20 (Fig. 11C). Functional plastidic ribosomes are crucial for the expression of the nuclear genes. However, the plastid could not assemble functional ribosomes because of the abnormal splicing of rpl2 and rps12 in the wsl5 mutant. Retrograde signaling from chloroplasts to the nuclear genome plays an important role in plant chloroplast development. The altered expression of these nuclear genes may be due to blocked retrograde signaling.

Fig. 11.

RNA-seq analysis of the wild type and wsl5 grown under low temperature and normal conditions. (A) Up-regulated differentially expressed genes comparing W2 and M2 and W3 and M3. (B) Down-regulated differentially expressed genes comparing W2 and M2 and W3 and M3. (C) GO analysis of genes differentially expressed between W2 and M2 and W3 and M3. W3 and W2 represent wild-type plants grown at 30 °C and 20 °C, respectively. M3 and M2 represent wsl5 plants grown at 30 °C and 20 °C, respectively.

Discussion

WSL5 encodes a chloroplast-targeted PPR protein that is essential for chloroplast development in juvenile plants under cold stress

PPR genes constitute a large multigene family in higher plants. PPR proteins are essential for plant growth and development, and most of them are involved in RNA editing, splicing, and regulation of stability of various organellar transcripts (Barkan and Small, 2014). In contrast to PPRs in A. thaliana, little is known about the functions of PPRs in rice. Here, we present a molecular characterization of the PPR gene WSL5 in rice. It has an RRM and 15 PPR motifs (Fig. S3 at Dryad). The WSL5 protein was predicted to contain a chloroplast transit peptide (cTP) in its N-terminal region, suggesting that the protein is one of the PPRs targeted to chloroplasts, and this was confirmed by subcellular localization experiments (Fig. 4D). The disruption of WSL5 under natural conditions led to abnormal chloroplasts and caused a variegated phenotype that affected both the chlorophyll content and the chloroplast ultrastructure up to the four-leaf stage, whereas the wsl5 mutant was albinic under cold stress (Fig. 2; Fig. S2 at Dryad). This finding suggests that the function of WSL5 in rice is essential for early chloroplast development under cold stress. This conclusion is further supported by the results of expression analysis. WSL5 was highly expressed in leaf sections L3 and L4 at the seedling stage. A high level of WSL5 was noted under low temperatures. Sequence alignment of homologous proteins using A. thaliana, maize, and rice showed that the mutant site in wsl5 is conserved within the RRM motif.

WSL5 is involved in splicing of plastidic genes and in ribosome biosynthesis

A large group of nuclear-encoded PPR proteins involved in RNA editing, splicing, stability, maturation, and translation is required for chloroplast development (Tan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). To date, six PPR proteins have been reported to be involved in RNA splicing of group II introns in chloroplasts. Among them, the maize PPR4 protein acts as an rps12 trans-splicing factor (Schmitz-Linneweber et al., 2006). Arabidopsis thaliana PPR protein OTP51 functions as a plastid ycf3-2 intron cis-splicing factor and OTP70 has been implicated in splicing of plastid transcript rpoC1 (de Longevialle et al., 2008; Chateigner-Boutin et al., 2011). In this study, the wsl5 mutant caused defects in the splicing of rpl2 and rps12 in rice (Figs 9, 10), implying that WSL5 probably controls chloroplast RNA intron splicing during early leaf development. The majority of those splicing factors act on distinct, but overlapping, intron subsets, and each intron has been shown to require multiple proteins (de Longevialle et al., 2010; Khrouchtchova et al., 2012). In rice, WSL can splice rpl2, while WSL4 can splice rpl2 and rps12 (Tan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017). WSL5 could not interact with WSL and WSL4 in the yeast system (data not shown). These three proteins are all involved in the splicing of rpl2. There is no functional redundancy among them. There may be an unknown regulatory mechanism to control the function of these three proteins. Further studies on searching for interacting partners of WSL5 will help to uncover the regulatory mechanism of the splicing of chloroplast genes.

Defective rps12 and rpl2 splicing could account for the white-stripe leaf phenotype and plastid ribosome deficiency in the wsl5 mutant (Figs 9, 10). We found that 23S and 16S rRNAs were decreased in the wsl5 mutant under cold stress (Fig. 7E, F). The lack of mature rps12 and rpl2 mRNA in the wsl5 mutant may severely affect ribosome functions in plastids. The absence of RPL2 and RPS12 protein resulted in the inability to make functional ribosomes. Thus, the ribosome assembly defect in wsl5 may also contribute to the wsl5 phenotype.

Possible mechanism of WSL5 regulating chloroplast development under cold stress and normal conditions

To study the molecular mechanism of WSL5 in regulating chloroplast development under different temperature conditions, we compared gene expression patterns in the wsl5 mutant and wild type by RNA-seq analysis. Our findings showed that under cold stress, WSL5 influences the expression of genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, oxidation–reduction processes, photosynthesis, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, chlorophyll biosynthesis process, and chloroplast development (Fig. 11; Dataset S2 at Dryad). Plastid thioredoxins are important for maintaining plastid oxidation–reduction balance (Bohrer et al., 2012). Many genes involved in regulating plastid oxidation–reduction balance were changed under C20 and C30 conditons, such as OsTRXm and OsTRXz (Fig. S10 at Dryad). OsTRXm is involved in regulation of activity of a target peroxiredoxin (Prx) through reduction of cysteine disulfide bridges (Chi et al., 2008). OsTRXz interacts with TSV to protect chloroplast development under cold stress (Sun et al., 2017). The large and small subunits of ribonucleotide reductase (RNR), V3 and St1, regulate the rate of deoxyribonucleotide production for DNA synthesis and repair (Yoo et al., 2009). V3 and St1 are repressed at constant 20 °C in wsl5, indicating that mutation in WSL5 leads to defects in DNA synthesis and repair in juvenile plants at low temperatures (Fig. S10 at Dryad). The expression of fatty acid metabolism genes OsFAH1, OsFAH2, and OsFAD7, and plastid starch metabolism genes AGPS2b and PHO1, was dramatically changed in wsl5 compared with the wild type at low temperatures (Fig. S10 at Dryad). Chloroplast development depends on co-operation between nuclear and chloroplast genes. The altered expression of these nuclear genes in the wsl5 mutant may be due to the absence of RPL2 and RPS12 proteins and thereby impede the transfer of retrograde signaling from plastids to the nucleus.

In conclusion, WSL5 influences the expression of plastid genes and biogenesis of plastid ribosomes. It is essential for chloroplast development in rice seedlings under cold stress by maintaining the retrograde signaling from plastids to the nucleus. Identification of this new PPR protein will help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of plastid development and ribosome biogenesis, and shed light on understanding chloroplast development in juvenile plants under cold stress.

Data deposition

The following data are available at Dryad Data Repository: http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.59185.

Dataset S1. Genes differentially expressed in the wild type and wsl5.

Dataset S2. Genes differentially expressed in the wild type and wsl5 under different temperature conditions.

Fig. S1. Comparison of pigment contents from the second (L2), third (L3), fourth (L4), and fifth (L5) leaves of five-leaf stage plants between the wild type and the wsl5 mutant.

Fig. S2. Transmission electron microscopy images of cells from the wild type and the wsl5 mutant grown under different temperature conditions.

Fig. S3. Alignment of WSL5 orthologs in maize and Arabidopsis.

Fig. S4. WSL5 was expressed in all tissues, especially during leaf development, according to Rice eFP Browser.

Fig. S5. GO analysis of genes differentially expressed between the wild type and wsl5.

Fig. S6. Pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed between the wild type and wsl5.

Fig. S7. Expression levels of chlorophyll synthesis genes in the wild type and wsl5.

Fig. S8. Editing efficiencies of rpl2 and atpA in the wild type and the wsl5 mutant.

Fig. S9. qRT-PCR analysis of rpl2 and rps12 transcripts in the wild type and the wsl5 mutant.

Fig. S10. qRT-PCR analysis of genes differently expressed in RNA-seq.

Table S1. Comparison of agronomic traits between the wild type and wsl5 under field conditions.

Table S2. Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Key Laboratory of Biology, Genetics and Breeding of Japonica Rice in Mid-lower Yangtze River, Ministry of Agriculture, PR China, and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production, and grants from The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0101801, 2016YFD0100101-08), Jiangsu Science and Technology Development Program (BE2017368), Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund project of Jiangsu Province (CX(16)1029), and Key Program of Science and Technology of Anhui Province (16030701068).

References

- Arnon DI. 1949. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiology 24, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan A, Small I. 2014. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 65, 415–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohrer AS, Massot V, Innocenti G, Reichheld JP, Issakidis-Bourguet E, Vanacker H. 2012. New insights into the reduction systems of plastidial thioredoxins point out the unique properties of thioredoxin z from Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 6315–6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chateigner-Boutin AL, des Francs-Small CC, Delannoy E, Kahlau S, Tanz SK, de Longevialle AF, Fujii S, Small I. 2011. OTP70 is a pentatricopeptide repeat protein of the E subgroup involved in splicing of the plastid transcript rpoC1. The Plant Journal 65, 532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tao L, Zeng L, Vega-Sanchez ME, Umemura K, Wang GL. 2006. A highly efficient transient protoplast system for analyzing defence gene expression and protein–protein interactions in rice. Molecular Plant Pathology 7, 417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi YH, Moon JC, Park JH, et al. 2008. Abnormal chloroplast development and growth inhibition in rice thioredoxin m knock-down plants. Plant Physiology 148, 808–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneille S, Lutz K, Maliga P. 2000. Conservation of RNA editing between rice and maize plastids: are most editing events dispensable?Molecular and General Genetics 264, 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Longevialle AF, Hendrickson L, Taylor NL, Delannoy E, Lurin C, Badger M, Millar AH, Small I. 2008. The pentatricopeptide repeat gene OTP51 with two LAGLIDADG motifs is required for the cis-splicing of plastid ycf3 intron 2 in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 56, 157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Longevialle AF, Small ID, Lurin C. 2010. Nuclearly encoded splicing factors implicated in RNA splicing in higher plant organelles. Molecular Plant 3, 691–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong X, Su Q, Lin D, Jiang Q, Xu J, Zhang J, Teng S, Dong Y. 2014. The rice OsV4 encoding a novel pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for chloroplast development during the early leaf stage under cold stress. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 56, 400–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammani K, Takenaka M, Miranda R, Barkan A. 2016. A PPR protein in the PLS subfamily stabilizes the 5'-end of processed rpl16 mRNAs in maize chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Research 44, 4278–4288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose M, Tasaki E, Sugita C, Sugita M. 2012. A PPR-DYW protein is required for splicing of a group II intron of cox1 pre-mRNA in Physcomitrella patens. The Plant Journal 70, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis P, López-Juez E. 2013. Biogenesis and homeostasis of chloroplasts and other plastids. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 14, 787–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Mei J, Gong XD, Xu JL, Zhang JH, Teng S, Lin DZ, Dong YJ. 2014. Importance of the rice TCD9 encoding α subunit of chaperonin protein 60 (Cpn60α) for the chloroplast development during the early leaf stage. Plant Science 215-216, 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminaka H, Morita S, Tokumoto M, Yokoyama H, Masumura T, Tanaka K. 1999. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA for an iron-superoxide dismutase in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 63, 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Araki M, Goto S, et al. 2008. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Research 36, D480–D484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khrouchtchova A, Monde RA, Barkan A. 2012. A short PPR protein required for the splicing of specific group II introns in angiosperm chloroplasts. RNA 18, 1197–1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusumi K, Iba K. 2014. Establishment of the chloroplast genetic system in rice during early leaf development and at low temperatures. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liere K, Weihe A, Börner T. 2011. The transcription machineries of plant mitochondria and chloroplasts: composition, function, and regulation. Journal of Plant Physiology 168, 1345–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Gong X, Jiang Q, Zheng K, Zhou H, Xu J, Teng S, Dong Y. 2015. The rice ALS3 encoding a novel pentatricopeptide repeat protein is required for chloroplast development and seedling growth. Rice 8, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xu W, Song Q, Tan L, Liu J, Zhu Z, Fu Y, Su Z, Sun C. 2013. Microarray-assisted fine-mapping of quantitative trait loci for cold tolerance in rice. Molecular Plant 6, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Lan J, Huang Y, et al. Data from: WSL5, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein, is essential for chloroplast biogenesis in rice under cold stress. Dryad Digital Repository doi: 10.5061/dryad.59185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Toole N, Hattori M, Andres C, Iida K, Lurin C, Schmitz-Linneweber C, Sugita M, Small I. 2008. On the expansion of the pentatricopeptide repeat gene family in plants. Molecular Biology and Evolution 25, 1120–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz-Linneweber C, Williams-Carrier RE, Williams-Voelker PM, Kroeger TS, Vichas A, Barkan A. 2006. A pentatricopeptide repeat protein facilitates the trans-splicing of the maize chloroplast rps12 pre-mRNA. The Plant Cell 18, 2650–2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikanai T, Fujii S. 2013. Function of PPR proteins in plastid gene expression. RNA Biology 10, 1446–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern DB, Goldschmidt-Clermont M, Hanson MR. 2010. Chloroplast RNA metabolism. Annual Review of Plant Biology 61, 125–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su N, Hu ML, Wu DX, et al. 2012. Disruption of a rice pentatricopeptide repeat protein causes a seedling-specific albino phenotype and its utilization to enhance seed purity in hybrid rice production. Plant Physiology 159, 227–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Zheng T, Yu J, et al. 2017. TSV, a putative plastidic oxidoreductase, protects rice chloroplasts from cold stress during development by interacting with plastidic thioredoxin Z. New Phytologist 215, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka M, Brennicke A. 2007. RNA editing in plant mitochondria: assays and biochemical approaches. Methods in Enzymology 424, 439–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenaka M, Zehrmann A, Verbitskiy D, Kugelmann M, Hartel B, Brennicke A. 2012. Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family proteins are required for RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids of plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 109, 5104–5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Tan Z, Wu F, et al. 2014. A novel chloroplast-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in splicing affects chloroplast development and abiotic stress response in rice. Molecular Plant 7, 1329–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillich M, Krause K. 2010. The ins and outs of editing and splicing of plastid RNAs: lessons from parasitic plants. New Biotechnology 27, 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Liu H, Zhai G, Wang L, Shao J, Tao Y. 2016. OspTAC2 encodes a pentatricopeptide repeat protein and regulates rice chloroplast development. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 43, 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Ren Y, Zhou K, et al. 2017. WHITE STRIPE LEAF4 encodes a novel P-type PPR pProtein required for chloroplast biogenesis during early leaf development. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Wang C, Zheng M, et al. 2016. WHITE PANICLE1, a Val-tRNA synthetase regulating chloroplast ribosome biogenesis in rice, is essential for early chloroplast development. Plant Physiology 170, 2110–2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SC, Cho SH, Sugimoto H, Li J, Kusumi K, Koh HJ, Iba K, Paek NC. 2009. Rice Virescent3 and Stripe1 encoding the large and small subunits of ribonucleotide reductase are required for chloroplast biogenesis during early leaf development. Plant Physiology 150, 388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. 2010. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biology 11, R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu QB, Huang C, Yang ZN. 2014. Nuclear-encoded factors associated with the chloroplast transcription machinery of higher plants. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu QB, Jiang Y, Chong K, Yang ZN. 2009. AtECB2, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein, is required for chloroplast transcript accD RNA editing and early chloroplast biogenesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant Journal 59, 1011–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehrmann A, Härtel B, Glass F, Bayer-Császár E, Obata T, Meyer E, Brennicke A, Takenaka M. 2015. Selective homo- and heteromer interactions between the multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290, 6445–6456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Cui X, Wang Y, Wu J, Gu X, Lu T. 2017. The RNA editing factor WSP1 is essential for chloroplast development in rice. Molecular Plant 10, 86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Zhang S, Dong J, Yang T, Mao X, Liu Q, Wang X, Liu B. 2017. A novel functional gene associated with cold tolerance at the seedling stage in rice. Plant Biotechnology Journal 15, 1141–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]