Abstract

Background

Obesity rates are increasing among HIV-infected individuals, but risk factors for obesity development on ART remain unclear.

Objectives

In a cohort of HIV-infected adults in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, we aimed to determine obesity rates before and after ART initiation and to analyse risk factors for obesity on ART.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed data from individuals initiating ART between 2000 and 2015. BMI was calculated at baseline (time of ART initiation). Participants who were non-obese at baseline and had ≥90 days of ART exposure were followed until the development of obesity or the end of follow-up. Obesity incidence rates were estimated using Poisson regression models and risk factors were assessed using Cox regression models.

Results

Of participants analysed at baseline (n = 1794), 61.3% were male, 48.3% were white and 7.9% were obese. Among participants followed longitudinally (n = 1567), 66.2% primarily used an NNRTI, 32.9% a PI and 0.9% an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI); 18.3% developed obesity and obesity incidence was 37.4 per 1000 person-years. In multivariable analysis, the greatest risk factor for developing obesity was the use of an INSTI as the primary ART core drug (adjusted HR 7.12, P < 0.0001); other risk factors included younger age, female sex, higher baseline BMI, lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count, higher baseline HIV-1 RNA, hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

Conclusions

Obesity following ART initiation is frequent among HIV-infected adults. Key risk factors include female sex, HIV disease severity and INSTI use. Further research regarding the association between INSTIs and the development of obesity is needed.

Introduction

Advancements in ART have led to vast improvements in the general health and life expectancy of HIV-infected individuals.1–3 Among individuals on suppressive ART, wasting has become less common and recent studies from both upper- and lower-income countries report weight gain irrespective of ART type.4–8 Additionally, many countries have reported an increasing prevalence of overweight and obese states in HIV-infected persons even prior to ART initiation, consistent with trends in the general population.6,9 As obesity rates rise, so does the risk for obesity-related complications.10–13 This is particularly worrisome as, even in the absence of obesity, HIV-infected individuals are already at high risk of non-AIDS events such as cardiovascular and fatty liver disease.14–16

Among HIV-infected individuals initiating ART, female sex,4,17 lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte counts4,17,18 and a lower baseline BMI4,6 have been associated with subsequent weight gain. However, associations between specific ART regimens and weight gain/obesity remain controversial.5,17–19

In a large cohort of HIV-infected, ART-treated adults in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, we aimed to calculate the prevalence of obesity prior to ART initiation and the incidence of obesity after ART initiation. Additionally, we aimed to determine specific risk factors associated with the development of obesity after ART initiation, including associations between weight gain and the use of specific ART drugs and classes.

Methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute of the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (INI/FIOCRUZ, CAAE 0032.0.009.000-10) and was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patient records/information were anonymized prior to analysis. The study was exempt from additional review by the Office of the Human Research Protection Program of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Study population

The HIV clinical cohort of INI/FIOCRUZ in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil includes a database of sociodemographic and clinical information on patients receiving HIV care. Trained extractors input information from medical records and laboratory results into the database biannually. Complete procedures regarding cohort data collection have been described elsewhere.20

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants included in the baseline obesity prevalence analysis were HIV-infected adults ≥18 years of age who started their first ART regimen between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2015. Women who became pregnant while on ART were excluded. In addition, participants without height data and without a weight recorded within 180 days prior to and 30 days after ART initiation were excluded. For participants with multiple eligible height and weight records, the height/weight recorded closest to the date of ART initiation was used to calculate the baseline BMI (defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters). Participants from the baseline obesity prevalence analysis were included in the longitudinal obesity incidence analysis if they were non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2) at the time of ART initiation and had ≥90 days of cumulative exposure to at least one NRTI and at least one ART core drug class [NNRTI, PI or integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)].

Study design

In this retrospective cohort study, participants included in the baseline analysis were assessed for the presence of obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) prior to ART initiation. Participants included in the longitudinal analysis were retrospectively followed for the development of obesity after ART initiation. In order to determine whether a participant developed obesity, all recorded weights after baseline and prior to 31 December 2015 were compiled into a list and the amount of time between sequential weight measurements was calculated. Every post-baseline weight was required to have been measured within 2 years of the previously recorded weight in order to be included. Weights that were recorded after a gap of >2 years, and any subsequent measurements, were excluded from the analysis. These data were excluded because significant weight changes occurring within these large time intervals could have occurred, but not been captured, and exclusion ensured that the weights being analysed provided an accurate longitudinal depiction of weight changes over the course of follow-up.

Follow-up for each participant started on their date of ART initiation. For participants who developed obesity, follow-up ended on the date of obesity diagnosis. For participants who did not develop obesity, follow-up ended on the date of their last clinic visit, date of death, 2 years after their last recorded weight measurement or 31 December 2015, whichever occurred first. Loss to follow-up (LTFU) was defined among participants whose last clinic visit was earlier than any of the above-mentioned dates.

Baseline BMI was categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥30 kg/m2). Age at ART initiation was calculated by subtracting the participant’s date of birth from their ART start date. Self-reported sex/gender was grouped as ‘male’, ‘female’ or ‘transgender woman’ (TW). Self-reported race/skin colour was categorized as ‘white’, ‘black’ or ‘mixed/other’. Education was self-reported and dichotomized as 0–8 years or >8 years. Baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count and HIV-1 RNA were defined as the values recorded closest to the date of ART initiation (within 180 days before and 30 days after ART initiation). Time from HIV diagnosis to ART start was calculated by subtracting the participant’s date of HIV diagnosis from their ART start date. History of hypertension was defined as any of the following recorded up to 30 days after ART initiation: diagnosis of hypertension, use of antihypertensive medication, systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg. History of diabetes mellitus was defined as any of the following recorded up to 30 days after ART initiation: history of diabetes mellitus, diabetes on treatment, fasting glucose level ≥126 mg/dL or haemoglobin A1c >6.5%. History of dyslipidaemia was defined as any of the following recorded up to 30 days after ART initiation: history of dyslipidaemia, use of lipid-lowering therapy, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >159 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 mg/dL, total cholesterol >239 mg/dL or triglycerides >199 mg/dL. History of an AIDS-defining illness was defined as any of the diagnoses included in the CDC 1993 definition diagnosed up to 30 days after ART initiation.21 Participants were classified as ‘ever smoker’ if they indicated any smoking history on a cross-sectional survey.22 Those missing data from the cross-sectional survey were classified as ‘ever smoker’ if their medical chart indicated a history of tobacco use.

The total duration of an individual’s time on ART during follow-up was calculated for the following drugs/classes: tenofovir, zidovudine, NNRTI, PI and INSTI. Time spent on abacavir was categorized with time on tenofovir, and time on didanosine, zalcitabine and stavudine was categorized with time on zidovudine. This was done due to the low frequency of use of these agents for ≥90 days (abacavir n = 111, didanosine n = 89, zalcitabine n = 1, stavudine n = 104). Each participant was classified according to the NRTI (tenofovir versus zidovudine) and core drug class (NNRTI versus PI versus INSTI) used for the greatest cumulative time during their follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were compared using χ2 tests for categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables. Obesity incidence was estimated per 1000 person-years of follow-up (PYFU) using Poisson regression models. Cox competing risk models (accounting for death and LTFU as competing events) were used to assess factors associated with incident obesity after ART initiation. Multivariable modelling was performed by including all covariates with a P value ≤0.20 in bivariate models and sequentially removing variables with the highest P value until only variables with a P value ≤0.05 remained. Age at ART initiation and most-used NRTI were forced into the final model. Date of ART initiation and end of follow-up date were both accounted for in the final model. Multiple imputation for missing data was performed for missing values of baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (n = 125) and log of HIV-1 RNA (n = 229). Continuous variables that were not linearly correlated with obesity (baseline BMI and baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count) were included in the models using restricted cubic splines to relax linearity assumptions.23 R (version 3.1.1) and libraries ‘survival’, ‘mi’, ‘rms’ and ‘mstate’ were used for the analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics and obesity prevalence

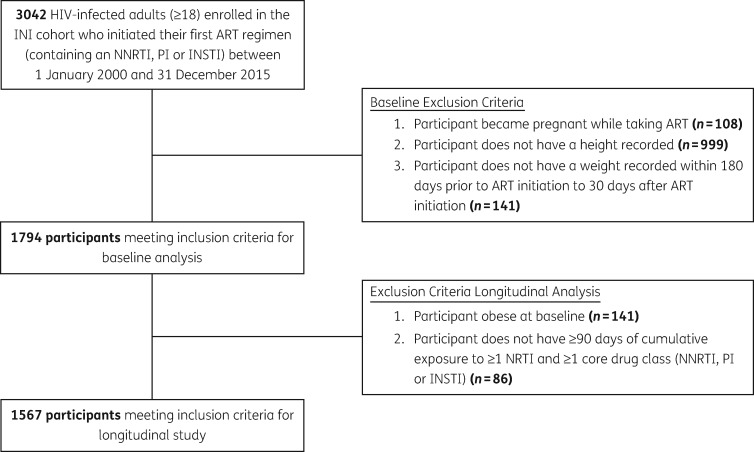

A total of 1794 individuals met inclusion criteria for the baseline analysis (Figure 1). At the time of ART initiation, 251 participants (14.0%) were underweight, 1012 (56.4%) were normal weight, 390 (21.7%) were overweight and 141 (7.9%) were obese. Median age at ART initiation was 36.3 years (IQR = 29.5–44.1). The majority of participants were male, white and had >8 years of schooling. Median baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count was 226 cells/mm³ (IQR = 79–350) and the median log HIV-1 RNA was 4.8 (IQR = 4.0–5.4). Median time from the date of HIV diagnosis to ART initiation was 0.6 years (IQR = 0.2–2.7). Participants had the following histories of comorbid disease: 12.9% hypertension, 4.9% diabetes mellitus, 27.0% dyslipidaemia, 38.8% AIDS-defining illness and 51.0% ever smoker. The prevalence of obesity at ART initiation increased over the study period (4.9% in 2000–03, 6.2% in 2004–07, 6.4% in 2008–11 and 12.0% in 2012–15) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study participant flow chart. INI, Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics at ART initiation by baseline BMI category, INI/FIOCRUZ, 2000–15

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), n = 251 (14.0%) | Normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), n = 1012 (56.4%) | Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), n = 390 (21.7%) | Obese (≥30 kg/m2), n = 141 (7.9%) | Total, n = 1794 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) at ART initiation | ||||||

| median (IQR) | 34.0 (27.9–43.2) | 35.7 (29.0–43.7) | 37.4 (31.5–44.8) | 39.8 (33.2–44.7) | 36.3 (29.5–44.1) | <0.0001 |

| <30 | 86 (34.3%) | 290 (28.7%) | 79 (20.3%) | 22 (15.6%) | 477 (26.6%) | <0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 84 (33.5%) | 361 (35.7%) | 143 (36.7%) | 50 (35.5%) | 638 (35.6%) | |

| 40–49 | 55 (21.9%) | 251 (24.8%) | 114 (29.2%) | 55 (39.0%) | 475 (26.5%) | |

| ≥50 | 26 (10.4%) | 110 (10.9%) | 54 (13.8%) | 14 (9.9%) | 204 (11.4%) | |

| Sex | 0.0009 | |||||

| male | 149 (59.4%) | 648 (64.0%) | 243 (62.3%) | 60 (42.6%) | 1100 (61.3%) | |

| female | 81 (32.3%) | 241 (23.8%) | 102 (26.2%) | 67 (47.5%) | 491 (27.4%) | |

| TW | 21 (8.4%) | 123 (12.2%) | 45 (11.5%) | 14 (9.9%) | 203 (11.3%) | |

| Race/skin colour | 0.0002 | |||||

| white | 90 (35.9%) | 489 (48.3%) | 224 (57.4%) | 63 (44.7%) | 866 (48.3%) | |

| black | 69 (27.5%) | 194 (19.2%) | 56 (14.4%) | 33 (23.4%) | 352 (19.6%) | |

| mixed/other | 92 (36.7%) | 329 (32.5%) | 110 (28.2%) | 45 (31.9%) | 576 (32.1%) | |

| Education level | <0.0001 | |||||

| 0–8 years | 177 (70.5%) | 505 (49.9%) | 148 (37.9%) | 73 (51.8%) | 903 (50.3%) | |

| >8 years | 74 (29.5%) | 507 (50.1%) | 242 (62.1%) | 68 (48.2%) | 891 (49.7%) | |

| Year of ART initiation | <0.0001 | |||||

| 2000–03 | 34 (13.5%) | 128 (12.6%) | 33 (8.5%) | 10 (7.1%) | 205 (11.4%) | |

| 2004–07 | 33 (13.1%) | 217 (21.4%) | 69 (17.7%) | 21 (14.9%) | 340 (19.0%) | |

| 2008–11 | 114 (45.4%) | 400 (39.5%) | 157 (40.3%) | 46 (32.6%) | 717 (40.0%) | |

| 2012–15 | 70 (27.9%) | 267 (26.4%) | 131 (33.6%) | 64 (45.4%) | 532 (29.7%) | |

| CD4+ T lymphocyte count (cells/mm³) | ||||||

| median (IQR) | 88 (29–207) | 212 (71–334) | 292 (185–400) | 323 (224–439) | 226 (79–350) | <0.0001 |

| <100 | 117 (46.6%) | 291 (28.8%) | 57 (14.6%) | 13 (9.2%) | 478 (26.6%) | <0.0001 |

| 100–249 | 62 (24.7%) | 261 (25.8%) | 93 (23.8%) | 29 (20.6%) | 445 (24.8%) | |

| 250–500 | 31 (12.4%) | 316 (31.2%) | 160 (41.0%) | 69 (48.9%) | 576 (32.1%) | |

| >500 | 9 (3.6%) | 77 (7.6%) | 61 (15.6%) | 23 (16.3%) | 170 (9.5%) | |

| missing | 32 (12.7%) | 67 (6.6%) | 19 (4.9%) | 7 (5.0%) | 125 (7.0%) | |

| Viral load (copies/mL) | ||||||

| median log10 (IQR) | 5.2 (4.5–5.7) | 4.8 (4.1–5.4) | 4.4 (3.8–5.2) | 4.4 (3.7–5.0) | 4.8 (4.0–5.4) | <0.0001 |

| <100 000 | 88 (35.1%) | 505 (49.9%) | 247 (63.3%) | 94 (66.7%) | 934 (52.1%) | <0.0001 |

| ≥100 000 | 117 (46.6%) | 372 (36.8%) | 105 (26.9%) | 37 (26.2%) | 631 (35.2%) | |

| missing | 46 (18.3%) | 135 (13.3%) | 38 (9.7%) | 10 (7.1%) | 229 (12.8%) | |

| Years from HIV diagnosis to ART start, median (IQR) | 0.3 (0.1–1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–2.2) | 1.7 (0.4–4.2) | 1.7 (0.6–5.0) | 0.6 (0.2–2.7) | <0.0001 |

| History of hypertension | 17 (6.8%) | 94 (9.3%) | 74 (19%) | 46 (32.6%) | 231 (12.9%) | <0.0001 |

| History of diabetes | 14 (5.6%) | 38 (3.8%) | 20 (5.1%) | 16 (11.3%) | 88 (4.9%) | 0.0013 |

| History of dyslipidaemia | 53 (21.1%) | 247 (24.4%) | 126 (32.3%) | 58 (41.1%) | 484 (27.0%) | <0.0001 |

| History of an AIDS-defining illness | 180 (71.7%) | 425 (42.0%) | 72 (18.5%) | 19 (13.5%) | 696 (38.8%) | <0.0001 |

| Ever smoker | 137 (54.6%) | 524 (51.8%) | 189 (48.5%) | 65 (46.1%) | 915 (51.0%) | 0.2733 |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

Factors associated with incident obesity after ART initiation

Of the 1794 individuals analysed at baseline, 1567 were non-obese and had ≥90 days of cumulative exposure to at least one NRTI and one core drug class, thus meeting inclusion criteria for the obesity incidence analysis. These individuals contributed 7657 PYFU with a median follow-up time of 4.1 years (IQR = 2.1–7.0). The median time to obesity diagnosis was 1.9 years (IQR = 0.9–3.6), while the median follow-up time for participants who did not develop obesity was 4.7 years (IQR = 2.5–7.4). A total of 1198 individuals (76.5%) gained weight over the study period, 688 (43.9%) increased their BMI category and 286 (18.3%) developed obesity. From baseline to end of study, the median BMI increased from 22.3 to 24.7 kg/m2 (P < 0.0001), with a median annual increase of 0.4 kg/m2/year.

Table 2 shows the longitudinal changes in BMI stratified by baseline BMI. For those underweight at baseline, the median BMI increased from 17.1 to 20.3 kg/m2, with a median annual increase of 0.6 kg/m2/year. A total of 65.9% of those underweight at baseline were classified into a higher BMI category at study end. For those of normal weight at baseline, the median BMI increased from 21.9 to 24.2 kg/m2, with a median annual increase of 0.4 kg/m2/year. A total of 40.3% of those of normal weight at baseline were categorized as overweight or obese at study end. For those overweight at baseline, the median BMI increased from 26.9 to 28.6 kg/m2, with a median annual increase of 0.3 kg/m2/year. A total of 40.0% of those overweight at baseline had become obese by the end of follow-up.

Table 2.

BMI changes after ART by baseline BMI category

| Baseline BMI category |

Total, n = 1567 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| underweight, n = 223 (14.2%) | normal weight, n = 969 (61.8%) | overweight, n = 375 (23.9%) | |||

| Final BMI category | <0.0001 | ||||

| underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 76 (34.1%) | 26 (2.7%) | 3 (0.8%) | 105 (6.7%) | |

| normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 122 (54.7%) | 552 (57%) | 45 (12.0%) | 719 (45.9%) | |

| overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 19 (8.5%) | 261 (26.9%) | 177 (47.2%) | 457 (29.2%) | |

| obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 6 (2.7%) | 130 (13.4%) | 150 (40.0%) | 286 (18.3%) | |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 17.1 (16.3–17.9) | 21.9 (20.3–23.3) | 26.9 (25.9–28.1) | 22.3 (19.9–24.9) | <0.0001 |

| Final BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 20.3 (18.0–23.0) | 24.2 (22.0–26.6) | 28.6 (26.1–30.3) | 24.7 (21.9–28.1) | <0.0001 |

| Annual change in BMI (kg/m2/year), median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.2–1.3) | 0.4 (0.0–1.0) | 0.3 (−0.1–1.5) | 0.4 (0.1–1.0) | 0.0039 |

| Incidence of obesity per 103 PYFU (95% CI) | |||||

| overall | 5.2 (2.3–11.6) | 25.5 (21.5–30.3) | 106.6 (90.9–125.1) | 37.4 (33.3–41.9) | <0.0001a |

| males | 4.6 (1.5–14.4) | 22.4 (17.8–28.3) | 97.1 (78.9–119.6) | 34.5 (29.6–40.2) | <0.0001a |

| females | 7.6 (2.4–23.4) | 39.8 (30.1–52.5) | 138.1 (103.4–184.4) | 49.8 (40.9–60.6) | <0.0001a |

| TW | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 13.2 (6.9–25.4) | 95.3 (57.5–158.1) | 25.4 (17.1–38.0) | <0.0001a |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

P values for baseline BMI as a continuous variable.

Table 3 shows the characteristics of participants who developed obesity after starting ART compared with those who remained non-obese, as well as the unadjusted HRs for incident obesity. Participants who became obese were more likely to have the following characteristics: female sex (24.4% females developed obesity versus 16.7% males and 13.1% TW, P = 0.0005), higher baseline BMI (median 25.3 versus 21.8 kg/m2, P < 0.0001), lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (median 152 versus 233 cells/mm3, P < 0.0001), higher baseline log HIV-1 RNA (median 5.0 versus 4.8, P = 0.0100), use of zidovudine as the most-used NRTI (zidovudine 21.3% versus tenofovir 16.1%, P = 0.0104), use of an INSTI as the most-used ART core drug class (INSTI 42.9% versus NNRTI 17.3% and PI 19.4%, P = 0.0346) and a history of hypertension (hypertension 30.1% versus no hypertension 16.8%, P < 0.0001). All the variables listed in Table 3 were considered for inclusion in the final multivariable model.

Table 3.

Factors associated with the development of obesity in HIV-infected individuals on ART

| Remained non-obese (BMI <30 kg/m2), n = 1281 (81.7%) | Developed obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), n = 286 (18.3%) | Total, n = 1567 | Crude HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up time (years), median (IQR) | 4.7 (2.5–7.4) | 1.9 (0.9–3.6) | 4.1 (2.1–7.0) | |

| Age (years) at ART initiation | ||||

| median (IQR) | 35.7 (29.0–43.8) | 36.5 (30.9–43.5) | 36.0 (29.3–43.8) | 1.02c (0.91–1.15) |

| <30 | 365 (28.5%) | 64 (22.4%) | 429 (27.4%) | |

| 30–39 | 450 (35.1%) | 114 (39.9%) | 564 (36.0%) | |

| 40–49 | 325 (25.4%) | 75 (26.2%) | 400 (25.5%) | |

| ≥50 | 141 (11.0%) | 33 (11.5%) | 174 (11.1%) | |

| Sex | ||||

| male | 815 (63.6%) | 163 (57.0%) | 978 (62.4%) | reference |

| female | 307 (24.0%) | 99 (34.6%) | 406 (25.9%) | 1.48 (1.15–1.90) |

| TW | 159 (12.4%) | 24 (8.4%) | 183 (11.7%) | 0.80 (0.52–1.23) |

| Race/skin colour | ||||

| white | 633 (49.4%) | 140 (49.0%) | 773 (49.3%) | reference |

| black | 241 (18.8%) | 57 (19.9%) | 298 (19.0%) | 1.27 (0.93–1.73) |

| mixed/other | 407 (31.8%) | 89 (31.1%) | 496 (31.7%) | 1.12 (0.86–1.46) |

| Education level | ||||

| 0–8 years | 626 (48.9%) | 155 (54.2%) | 781 (49.8%) | reference |

| >8 years | 655 (51.1%) | 131 (45.8%) | 786 (50.2%) | 0.94 (0.74–1.18) |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| median (IQR)a | 21.8 (19.4–24.0) | 25.3 (22.3–27.7) | 22.3 (19.9–24.9) | 1.15 (1.04–1.28) |

| underweight (<18.5) | 217 (16.9%) | 6 (2.1%) | 223 (14.2%) | |

| normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 839 (65.5%) | 130 (45.5%) | 969 (61.8%) | |

| overweight (25–29.9) | 225 (17.6%) | 150 (52.4%) | 375 (23.9%) | |

| Baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (cells/mm³) | ||||

| median (IQR)a,b | 233 (90–355) | 152 (48–287) | 222 (78–343) | 0.74d (0.61–0.90) |

| <100 | 319 (24.9%) | 102 (35.7%) | 421 (26.9%) | |

| 100–249 | 331 (25.8%) | 72 (25.2%) | 403 (25.7%) | |

| 250–500 | 428 (33.4%) | 68 (23.8%) | 496 (31.7%) | |

| >500 | 122 (9.5%) | 16 (5.6%) | 138 (8.8%) | |

| missing | 81 (6.3%) | 28 (9.8%) | 109 (7.0%) | |

| Baseline viral load (copies/mL) | ||||

| median log10 (IQR)b | 4.8 (4.0–5.4) | 5.0 (4.2–5.5) | 4.8 (4.1–5.4) | 1.09 (0.96–1.23) |

| <100 000 | 681 (53.2%) | 119 (41.6%) | 800 (51.1%) | |

| ≥100 000 | 452 (35.3%) | 115 (40.2%) | 567 (36.2%) | |

| missing | 148 (11.6%) | 52 (18.2%) | 200 (12.8%) | |

| Years from HIV diagnosis to ART start, median (IQR) | 0.6 (0.2–2.5) | 0.5 (0.2–2.3) | 0.6 (0.2–2.5) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) |

| Most-used NRTI | ||||

| TDF | 767 (59.9%) | 147 (51.4%) | 914 (58.3%) | reference |

| AZT | 514 (40.1%) | 139 (48.6%) | 653 (41.7%) | 0.86 (0.68–1.09) |

| Most-used ART core drug class | ||||

| NNRTI | 858 (67.0%) | 180 (62.9%) | 1038 (66.2%) | reference |

| PI | 415 (32.4%) | 100 (35.0%) | 515 (32.9%) | 1.04 (0.82–1.33) |

| INSTI | 8 (0.6%) | 6 (2.1%) | 14 (0.9%) | 8.57 (3.77–19.47) |

| History of hypertension | 121 (9.4%) | 52 (18.2%) | 173 (11.0%) | 1.92 (1.42–2.60) |

| History of diabetes | 47 (3.7%) | 16 (5.6%) | 63 (4.0%) | 1.74 (1.05–2.88) |

| History of dyslipidaemia | 329 (25.7%) | 70 (24.5%) | 399 (25.5%) | 1.03 (0.78–1.34) |

| History of an AIDS-defining illness | 489 (38.2%) | 125 (43.7%) | 614 (39.2%) | 1.11 (0.88–1.40) |

| Ever smoker | 676 (52.8%) | 145 (50.7%) | 821 (52.4%) | 0.84 (0.66–1.06) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

TDF, tenofovir; AZT, zidovudine.

Variable included in model using restricted cubic spline.

Missing values imputed in the models.

Crude HR per 10 year increase in age.

Crude HR per 100 cell increase in CD4+ T lymphocyte count.

The overall incidence of obesity was 37.4 per 1000 PYFU. Patients who were overweight at baseline had a higher incidence of obesity (106.6 per 1000 PYFU) than those who were underweight and normal weight (5.2 and 25.5 per 1000 PYFU, respectively). Females had a higher incidence of obesity (49.8 per 1000 PYFU) compared with males and TW (34.5 and 25.5 per 1000 PYFU, respectively) (Table 2). In addition, those who started ART between the years 2000 and 2003 had a lower incidence of obesity (20.1 per 1000 PYFU) than those who started ART between 2004 and 2007, between 2008 and 2011, and between 2012 and 2015 (39.7, 44.1 and 43.2 per 1000 PYFU, respectively) (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

In individuals primarily using an INSTI (n = 14), the incidence of obesity was higher than those primarily using an NNRTI (n = 1038) or PI (n = 515) (370.7 versus 36.0 and 37.8 per 1000 PYFU, respectively). In addition, those using an INSTI as their most-used ART core drug had greater annual BMI change versus NNRTI and PI (median gain of 1.6 versus 0.4 and 0.4 kg/m2/year, respectively, P = 0.1569) and shorter time to obesity diagnosis (median 1.0 versus 1.9 and 1.9 years, respectively, P = 0.1850). Among those classified under INSTI (10 men, 3 women, 1 TW), obesity incidence was higher for women than men (1073.2 versus 344.4 per 1000 PYFU, respectively) and women experienced greater annual BMI gain than men (median of 5.0 versus 0.5 kg/m2 per year) (Tables S2 and S3).

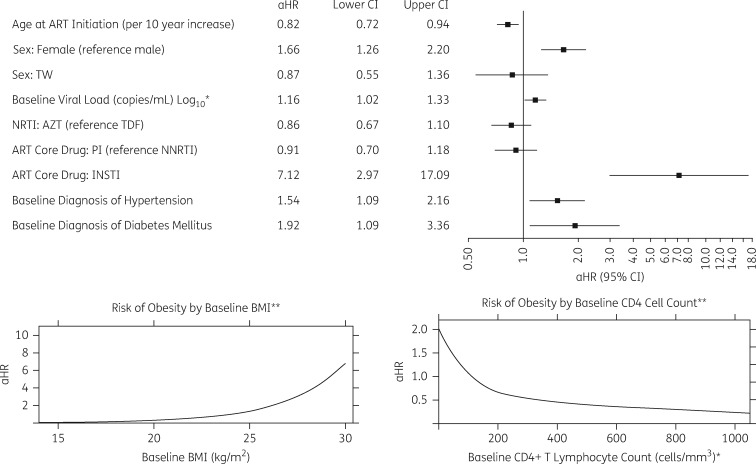

In multivariable models accounting for competing risks, the following variables were associated with the development of obesity after ART initiation: younger age at ART initiation [adjusted HR (aHR) 0.82 per 10 year increase, P = 0.0048], female sex (aHR 1.66, P = 0.0003), higher baseline BMI (using restricted cubic splines), lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count (using restricted cubic splines), higher baseline HIV-1 RNA (aHR 1.16, P = 0.0275), use of an INSTI as the ART core drug (aHR 7.12, P < 0.0001), and baseline diagnoses of hypertension (aHR 1.54, P = 0.0136) and diabetes mellitus (aHR 1.92, P = 0.0238) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Factors associated with incident obesity after multivariable analysis. Note: date of ART initiation and end of follow-up date were accounted for in multivariable analysis. AZT, zidovudine; TDF, tenofovir. *Missing values imputed in the models. **Variables included in the models using restricted cubic splines.

Discussion

We aimed to characterize obesity rates and risk factors in HIV-infected adults before and after ART initiation. We observed that, at the time of ART initiation, 7.9% of participants were obese and this prevalence increased over the study period (2000–15). This trend can likely be attributed to a combination of increasing obesity incidence worldwide24 and to 2012–13 international guidelines recommending earlier initiation of ART.25,26 While the prevalence of obesity at ART initiation observed in our cohort was lower than that reported in the Brazilian general population, where the prevalence of obesity steadily rose from 11.9% in 2006 to 17.9% in 2014,27 the prevalence of obesity at ART initiation increased by calendar year in our cohort, as did the incidence rate of obesity after ART initiation.

Among non-obese individuals initiating ART, 18.3% developed obesity with a rapid median time of 1.9 years from ART initiation to obesity diagnosis. The greatest risk factor for developing obesity after ART initiation was having an INSTI as the most-used ART core drug class. Other risk factors included younger age, female sex, higher baseline BMI, lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte count, higher baseline HIV-1 RNA, and baseline diagnoses of hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

The observed associations between female sex and weight gain after ART initiation have been previously documented.5,17 Individuals who were overweight at baseline had a greater risk of developing obesity because their starting BMIs were closer to the obesity threshold; however, underweight individuals had the greatest annual change in BMI. This may be explained in part by the extreme relative immune reconstitution that can occur in individuals with more advanced HIV disease after ART initiation.4 This same explanation can be used to justify associations between obesity development and lower baseline CD4+ T lymphocyte counts and higher baseline HIV-1 RNA levels. This explanation may also help clarify why younger participants were more likely to develop obesity after ART use, as younger participants may have more robust immunological response to ART, making them more susceptible to weight gain. Finally, associations between obesity development and baseline hypertension and diabetes mellitus likely result from the fact that these conditions were more prevalent in individuals who were overweight at baseline compared with those who were of normal weight.

Importantly, the greatest risk factor for developing obesity in our cohort was having an INSTI as the most-used ART core drug class. Compared with those who primarily used an NNRTI or PI, participants who primarily used an INSTI had 10-fold higher obesity incidence, 4-fold greater annual BMI gain and nearly twice as rapid a time to obesity. Of note, females classified under INSTI had remarkably high rates of obesity and annual BMI gain. When adjusted for potential confounding, having an INSTI as the most-used ART core drug was associated with a >7-fold increase in the risk of developing obesity. Although the sample size of those classified under INSTI was small (n = 14), the magnitude of this association is impressive and has only recently been described in the literature. Menard et al.28 looked at weight changes in 462 individuals prescribed dolutegravir plus abacavir/lamivudine or tenofovir/emtricitabine and found that after 1 year of therapy, mean weight gain was 3 kg. This weight gain was significant for women and showed a tendency toward significance for men. Similarly, Norwood et al.29 found that, in individuals with ≥2 years of exposure to efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine, those who were switched to an INSTI-containing regimen (dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine or raltegravir/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine or elvitegravir/cobicistat/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) gained 2.9 kg after 18 months, compared with a 0.7 kg gain in those switched to a PI-containing regimen and a 0.9 kg gain in those who remained on efavirenz/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine.

Potential mechanisms explaining the association between weight gain and INSTI use are currently unknown. One possible explanation is that INSTIs cause an especially rapid drop in HIV-1 RNA,30 and HIV-1 RNA is positively correlated with resting energy expenditure.31 Thus, individuals taking INSTIs may experience greater short-term decreases in resting energy expenditure, predisposing them to weight gain. This hypothesis was unable to be assessed in our cohort as we did not have sufficient HIV-1 RNA data post-ART initiation to explore if decreases in HIV-1 RNA correlated with weight gain. A second possible explanation is that raltegravir has higher levels of tissue penetration compared with other classes of ART,32 which could result in as yet unidentified mechanisms of metabolic change that drive weight gain.

It should be noted that of the 14 individuals who had an INSTI as their most-used ART core drug, 50% had a baseline diagnosis of TB compared with 24% in the total cohort. The longitudinal multivariable analysis accounted for TB in the variable ‘history of an AIDS-defining illness’. When forcing TB into the final multivariable analysis, INSTIs were still associated with an increased risk of obesity (aHR 5.5, P = 0.0002) (Table S4). Additionally, when repeating the multivariable analysis in exclusively TB-infected individuals (n = 383), the association between INSTIs and an increased risk of obesity remained (aHR 6.9, P = 0.0006) (Table S5). Thus, even when adjusting for the potential confounding effect of TB, INSTIs were still associated with an increased risk of developing obesity.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not have data regarding caloric intake, alcohol use, menopausal status, concomitant medication usage that may have caused weight changes (i.e. metformin, psychiatric medications), or physical activity levels in participants, as would be ideal. Second, we were forced to rely on BMI as the sole marker of obesity because we did not have data from other anthropomorphic measurements, such as waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Third, as this was an observational study, participants did not have weights recorded at regularly scheduled intervals. In order to account for this, each participant was screened to ensure that they did not have a period of >2 years where they did not have a weight recorded. Another limitation is that NRTI usage and ART core drug usage were classified into mutually exclusive categories. While this categorization allowed for the comparison of obesity rates between NRTIs and core drug classes, it could not account for the overlap effects of using combination ART. However, it should be noted that 79% (n = 1231) of the participants had exposure to only one ART core drug class for ≥90 days during follow-up and associations between the specific NRTIs and obesity were not observed. In addition, of the six individuals who took an INSTI as their most-used ART core drug and developed obesity, five (83%) had no exposure to an NNRTI- or PI-based regimen for ≥90 days. Finally, due to the years of study follow-up included, the overall numbers of participants with INSTI exposure were low. However, this also makes the effect size and statistical significance more striking. Additionally, of the participants who took an INSTI as their most-used ART core drug, 92.9% (n = 13) used raltegravir. Thus, it is unknown whether our results will be applicable to the more recent generations of INSTIs.

A major strength of this study is the high number of female and TW participants, which allowed for the determination of sex-/gender-specific risk factors. Other strengths included the diversity of the cohort in terms of race and education, the high median follow-up time and the number of years that the study spanned.

Conclusions

Obesity is a major concern in the HIV-infected population before and after ART initiation. Both the prevalence of obesity in HIV-infected, ART-naive individuals and the incidence of obesity after ART initiation continue to increase. Obesity prevention should be discussed at the time of ART initiation in order to reduce incidence and minimize long-term sequelae. Further research with a larger number of INSTI-exposed individuals is needed in order to validate the association between INSTIs and obesity and to elucidate potential mechanisms of weight gain in INSTI-treated individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

These data were previously published as an abstract at IDWeek 2017 (Abstract 1684).

We would like to thank the INI/FIOCRUZ staff for their dedication to patient care and to maintaining the clinical database. In addition, we would like to thank the patients of the INI cohort for allowing this research to be possible.

Funding

This work was supported by the South American Program in HIV Prevention Research, National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Mental Health (R25 H087222 to D. R. B.); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K23 AI110532 to J. E. L.); the National Institutes of Health (R25 MH087222 to J. L. C.); and the National Institutes of Health-funded Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet), a member cohort of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (leDEA) (U01AI069923).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Tables S1–S5 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS. et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One 2013; 8: e81355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boyd MA. Improvements in antiretroviral therapy outcomes over calendar time. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009; 4: 194–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodger AJ, Lodwick R, Schechter M. et al. Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. AIDS 2013; 27: 973–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ezechi LO, Musa ZA, Otobo VO. et al. Trends and risk factors for obesity among HIV positive Nigerians on antiretroviral therapy. Ceylon Med J 2016; 61: 56.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guehi C, Badjé A, Gabillard D. et al. High prevalence of being overweight and obese HIV-infected persons, before and after 24 months on early ART in the ANRS 12136 Temprano trial. AIDS Res Ther 2016; 13: 12.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Lau B. et al. Rising obesity prevalence and weight gain among adults starting antiretroviral therapy in the United States and Canada. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2016; 32: 50–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amorosa V, Synnestvedt M, Gross R. et al. A tale of 2 epidemics: the intersection between obesity and HIV infection in Philadelphia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005; 39: 557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gomes A, Reyes EV, Garduno LS. et al. Incidence of diabetes mellitus and obesity and the overlap of comorbidities in HIV+ Hispanics initiating antiretroviral therapy. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0160797.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lake JE, Stanley TL, Apovian CM. et al. Practical review of recognition and management of obesity and lipohypertrophy in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 1422–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N. et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2009; 9: 88.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Sullivan L. et al. Overweight and obesity as determinants of cardiovascular risk: the Framingham experience. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162: 1867–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berrahmoune H, Herbeth B, Samara A. et al. Five-year alterations in BMI are associated with clustering of changes in cardiovascular risk factors in a gender-dependant way: the Stanislas study. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 1279.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Poirier P, Eckel RH.. Obesity and cardiovascular disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2002; 4: 448–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paisible A-L, Chang C-CH, So-Armah KA. et al. HIV infection, cardiovascular disease risk factor profile, and risk for acute myocardial infarction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 68: 209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C. et al. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: 2506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Crum-Cianflone N, Dilay A, Collins G. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among HIV-infected persons. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 50: 464–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lakey W, Yang L-Y, Yancy W. et al. From wasting to obesity: initial antiretroviral therapy and weight gain in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2013; 29: 435–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crum-Cianflone N, Roediger MP, Eberly L. et al. Increasing rates of obesity among HIV-infected persons during the HIV epidemic. PLoS One 2010; 5: e10106.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McComsey GA, Moser C, Currier J. et al. Body composition changes after initiation of raltegravir or protease inhibitors: aCTG A5260s. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 853–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grinsztejn B, Veloso VG, Friedman RK. et al. Early mortality and cause of deaths in patients using HAART in Brazil and the United States. AIDS 2009; 23: 2107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. CDC. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Recomm Rep 1992; 41: 1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Torres TS, Luz PM, Derrico M. et al. Factors associated with tobacco smoking and cessation among HIV-infected individuals under care in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One 2014; 9: e115900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shepherd BE, Rebeiro PF.. Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology. Assessing and interpreting the association between continuous covariates and outcomes in observational studies of HIV using splines. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 74: e60–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014: “Attaining the Nine Global Noncommunicable Diseases Targets; A Shared Responsibility”. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF. et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2012 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA panel. JAMA 2012; 308: 387–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. WHO. Clinical Guidance across the Continuum of Care: Antiretroviral Therapy. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/art/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minesterio da Saude. VIGITEL Brasil 2014: Vigilância de Fatores de Risco e Proteção para Doenças Crônicas por Inquérito Telefônico.2014. Brazil.

- 28. Menard A, Meddeb L, Tissot-Dupont H. et al. Dolutegravir and weight gain: an unexpected bothering side effect? AIDS 2017; 31: 1499–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Norwood J, Turner M, Bofill C. et al. Weight gain in persons with HIV switched from efavirenz-based to integrase strand transfer inhibitor-based regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017; 76: 527–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Lazzarin A. et al. Safety and efficacy of raltegravir-based versus efavirenz-based combination therapy in treatment-naive patients with HIV-1 infection: a multicentre, double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mulligan K, Tai VW, Schambelan M.. Energy expenditure in human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med 1997; 336: 70–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Patterson KB, Prince HA, Stevens T. et al. Differential penetration of raltegravir throughout gastrointestinal tissue: implications for eradication and cure. AIDS 2013; 27: 1413–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.