Abstract

Objective

When a child is diagnosed with cancer, problems may arise in family relationships and negatively affect child adjustment. The current study examined patterns of spillover between marital and parent–child relationships to identify targets for intervention aimed at ameliorating family conflict.

Method

Families (N = 117) were recruited from two US children’s hospitals within 2-week postdiagnosis to participate in a short-term prospective longitudinal study. Children with cancer were 2–10 years old (M = 5.42 years, SD = 2.59). Primary caregivers provided reports of marital and parent–child conflict at 1-, 6-, and 12-month postdiagnosis.

Results

Results indicated that a unidirectional model of spillover from the marital to the parent–child relationship best explained the data. In terms of specific temporal patterns, lower marital adjustment soon after diagnosis was associated with an increase in parent–child conflict 6 months later, though this pattern was not repeated in the latter 6 months of treatment.

Conclusion

Targeting problems in marital relationships soon after diagnosis may prevent conflict from developing in the parent–child relationship.

Keywords: cancer and oncology, family functioning, parents

When a child is diagnosed with cancer, families may experience increases in conflict, as all family members cope with the diagnosis, readjust family roles, and adapt to lifestyle changes to accommodate the child’s treatment (Lavee, 2005; Long & Marsland, 2011; Pai et al., 2007; Van Schoors et al., 2015). Particularly during the first year of treatment, conflict may arise in multiple subsystems within the family, including the marital and parent–child systems (Burns et al., 2017; Dahlquist et al., 1993; Marine & Miller, 1998; Pai et al., 2007). Family conflict has been recognized as a strong predictor of child adjustment (Cummings, Davies & Campbell, 2000). Much work to date has posited that high levels of conflict in the family may threaten children’s emotional security (Davies & Cummings, 1994), thereby eliciting problems regulating emotional arousal (Katz, Kramer & Gottman, 1992). Among healthy populations, children who experience high levels of conflict are more likely to have a variety of adjustment problems, including externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, both concurrently and over time (Grych & Fincham, 1990; Katz & Gottman, 1993). Among children with cancer, family functioning has also been linked to children’s psychological adjustment (Van Schoors, Caes, Knoble, et al., 2017).

While many families exhibit resilient outcomes in the face of a child’s cancer diagnosis and treatment (Van Schoors et al., 2015), a number of studies have suggested that a subset of families experiences marital distress and increased parent–child conflict after a child’s diagnosis. However, no studies to date have examined how these family subsystems influence one another over time in the context of cancer. Although such questions have not been addressed among families with a chronically ill child, Engfer’s spillover hypothesis (1988) has been widely applied to examine such patterns of influence in families with healthy children (Gerard, Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2006; Katz & Gottman, 1996). Engfer (1988) posits that patterns of interaction and emotional displays in one subsystem (e.g., the marital relationship) may propagate similar patterns in other subsystems (e.g., the parent–child relationship). Given widespread support for this hypothesis among families with healthy children (Cox, Paley & Harter, 2001; Erel & Burman, 1995), this framework may also be of utility in understanding similar cascades in families of children with cancer.

Understanding how spillover between the marital and parent–child relationship operates in the context of pediatric cancer is needed to inform intervention and prevention efforts. First, if spillover is occurring over time, early intervention may be useful to prevent such cascades from unfolding. Second, understanding the direction of spillover would allow for interventions to be appropriately targeted, thereby minimizing burden on families. For example, if the quality of the marital relationship affects the parent–child relationship rather than the reverse, targeting the marital relationship early could prevent this spillover without need to involve the child. During treatment, families experience high stress and significant demands on their time (McCaffrey, 2006). Likewise, providers often have limited resources to implement supportive services for families. Identifying whether and how these relationships influence one another over time could inform the development of appropriately targeted interventions that would be maximally effective while minimizing burden on families and providers.

Pediatric Cancer, Family Conflict, and Child Adjustment

Only a small number of studies to date have examined how specific dyadic relationships within the family are affected by pediatric cancer. Among studies examining specific family dyads, most have focused on the marital relationship, yielding mixed results. For instance, Burns et al., (2017) found that about 25% of mothers and 21% of fathers reported significant marital distress at diagnosis, and 36% of mothers and 43% of fathers reported significant distress after 2 years. Similarly, Dahlquist and colleagues (1993) found that about 25% of couples reported significant marital distress shortly after their child’s diagnosis. Fife, Norton, and Groom (1987) found that on average, marital satisfaction was lower than the well-adjusted range. In contrast, other work with parents of children with cancer has suggested no differences compared with families with healthy children (Larson, Wittrock & Sandgren, 1994; Leventhal-Belfer, Bakker & Russo, 1993). A recent systematic review reported that many couples fare well after their child’s diagnosis, but a subset declines in general marital adjustment and satisfaction particularly in the first year postdiagnosis (Van Schoors et al., 2017). Relative to studies of the marital relationship, few studies have directly examined conflict in the parent–child relationship. To our knowledge, only one study to date has directly assessed parent–child conflict during pediatric cancer treatment. Marine and Miller (1998) found that adolescents with cancer reported higher conflict with both mothers and fathers compared with a noncancer sample.

Although conclusions are limited by few studies and some mixed results, findings collectively suggest that some families may experience distress in the marital and parent–child relationships during cancer treatment. This may be of particular importance given the link between family conflict and child adjustment. Indeed, in a recent meta-analysis, Van Schoors and colleagues (2017) identified that more family conflict was associated with poorer child adjustment across seven studies of families of children with cancer. However, no studies to date have examined interrelations between family relationships during cancer treatment. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand how strain in one relationship may temporally affect others to inform appropriate timing and targets for maximally efficient intervention.

Spillover of Family Conflict in Healthy Populations

While spillover between family relationships has not been addressed among families in which a child has cancer or another chronic illness, research on healthy families has identified three patterns or directions of spillover between marital and parent–child relationships. First, much work to date has found evidence of spillover from the marriage to the parent–child relationship. In a meta-analysis of 68 studies, Erel and Burman (1995) reported pervasive support for spillover between marital and parent–child relationships, suggesting that discord or dissatisfaction in the marriage may lead to troubled parent–child relationships (see also: Cox et al., 2001; Gerard, Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2006). Fewer studies have examined the second potential direction of influence in which conflict in the parent–child relationship may spill over into the marital relationship. A few studies have found direct evidence for spillover in this direction (Jenkins et al., 2005; VanderValk et al., 2007), while others have not (Almeida, Wethington & Chandler, 1999; Erel & Burman, 1995).

Only two studies have considered a third direction of influence—reciprocal and/or transactional pathways. In other words, that spillover may occur in both directions simultaneously, or may occur from one subsystem to another and in turn back to the subsystem in which the conflict originated. From a family systems perspective, the marital and parent–child relationships are closely intertwined and likely influence one another over time (Fincham, Grych, & Osborne, 1994). Margolin, Christensen, and John (1996) found evidence for reciprocal influence in daily family tensions among families of children aged 3–13 years, and Sears and colleagues (2016) found similar spillover of daily tensions between parent–child relationships and spousal relationships in families of children aged 8–13 years. To gain a better understanding of these patterns, more multiwave longitudinal research is needed in which reciprocal relations can be rigorously tested and temporal precedence can be used to suggest pathways of influence.

Current Study

The current study examines temporal relations between marital adjustment and parent–child conflict at three time points through the first year of cancer treatment. Two research questions were examined: (1) Is spillover occurring between the marital and parent–child relationships during the first year postdiagnosis, and if so, is this spillover unidirectional or bidirectional? (2) Do any specific patterns exist regarding how this cascade unfolds over time? We predict that there will be spillover between the marital and parent–child dyads and that it will be bidirectional in nature, meaning marital and parent–child relationships will influence one another over time.

Method

Participants

Families were part of a larger study examining pediatric cancer and family adjustment (N = 159). Families in the current study (N = 117) were those with a child aged 2–10 years (M = 5.42 years, SD = 2.59) who was recently diagnosed with cancer, and primary and secondary caregivers who were married (90.6%) or romantically involved (9.4%). Most children with cancer were identified as White/Caucasian (87.4%) by the primary caregiver, with the remaining identified as Black/African-American (2.7%), Asian (1.8%), American Indian (.9%), or other (7.2%). Additionally, 18.0% of participants identified as ethnically Hispanic. Children were diagnosed with leukemia (40.2%), lymphoma (11.1%), sarcoma (9.4%), Wilm’s tumor (7.7%), neuroblastoma (3.4%), or another form of cancer (6.8%). The remaining 21.4% of the children were diagnosed with a central nervous system tumor. Families were asked to self-identify the primary caregiver based on who spent the most time with the child with cancer. Most families identified the mother (86.3%). Primary caregivers were on average 35.04 years old (SD = 7.32), White/Caucasian (91.7%), and had completed college (58.0%). For married caregivers, the average length of marriage was 9.32 years (SD = 5.55). Median annual family income was between $70,000 and $79,000.

Procedure

Participating families were recruited through two hospitals in urban areas of the northwestern and southeastern United States, and approached within 2 weeks of diagnosis. Eligible participants were identified through a new diagnosis registry within each hospital, and approached either by a provider during a clinic appointment for outpatient families or by a nurse for inpatient families. To be considered eligible, families needed to be English-speaking and have a child newly diagnosed with cancer with no history of developmental delay. Across both sites, of the 502 eligible families, 209 were approached, 176 enrolled, and 159 completed at least one study component. A greater number of families were eligible, approached, and enrolled at the northwestern site, though rate of decline was also higher (44 vs. 22%). Primary reasons that eligible families were not approached included: (a) physician did not consent to approach because child was too ill; (b) families were recruited by a competing study; and (c) at the northwestern site, there was difficulty completing an Insitutional Review Board-required two-step approach process within the study window. Of the families approached who did not enroll, common reasons for refusal were excessive time required or no reason was given (e.g., family did not respond to calls or letters from study team). Consent was attained from the self-identified primary caregiver and assent from the child with cancer. No children died while on study, and all families remained eligible for the duration of the study.

Data were collected over a 12-month period via questionnaire packets completed by primary caregivers and returned through the mail. The initial (Time 1) packet was received 1.5-month postdiagnosis on average (SD = 0.79), and was intended to assess family relationships within the past month (e.g., the first month after diagnosis). The Time 2 packet was sent 6-months after receipt of the Time 1 questionnaires. Caregivers had a 2-week window to return the packet after this date. If it was not received within that window, data were considered missing for that month. The same procedure was used for Time 3 (e.g., packet was sent 12-months after receipt of Time 1). Completion of each time point was not necessary to remain eligible for the next time point. While all families remained eligible through the duration of the study, some families did not complete data at each time point. Specifically, 97.5% of families completed questionnaires at Time 1, 80% at Time 2, and 58.4% at Time 3. Missing data were accounted for in all analyses (see data analytic strategy). For the current study, these time points were selected to represent relevant phases of the first year of treatment to capture the dynamic experience of families over time. Specifically, the first month after diagnosis is often a highly stressful time for families during which parents may be exhibiting high levels of distress and conflict may be more likely to arise (Pai et al., 2007); at 6-month postdiagnosis, life may be less chaotic, as the family has adjusted to a new lifestyle accommodating treatment; finally, the 12th month represents the end of the first year of treatment, when some families may be transitioning or have transitioned to survivorship. For additional information regarding study procedures, see (Katz et al., in press). Study procedures received Insitutional Review Board approval from all participating institutions.

Measures

Demographic and Medical Information

Demographic information was collected from families via primary caregiver report questionnaires included in the initial questionnaire packet. Questionnaires assessed child and family information, including age and ethnicity of child with cancer and caregivers, caregivers’ relationships to the child with cancer, caregiver marital status, length of marriage, family income, and number and age of siblings. Diagnosis and treatment intensity information were extracted from medical records by research assistants. Treatment intensity was coded using the Intensity of Treatment Rating (ITR-3, Kazak et al., 2012). This measure provides a treatment intensity score of 1 (least intensive)–4 (most intensive) based on diagnosis, stage/level of disease, and number or type of treatment modalities.

Marital Adjustment

Marital adjustment was assessed through primary caregiver report using the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS; Spanier, 1976). The DAS is a well-validated 35-item self-report questionnaire used to assess marital adjustment. This measure yields an overall dyadic adjustment score computed as the sum of all items, with higher scores indicating better adjustment. Wood, Crane, Schaalje, and Law (2005) established ranges for mildly distressed (96–107), moderately distressed (80–95.9), and severely distressed (<80) couples. Couples scoring >107 are considered to be in the happily married range. This measure has been shown to reliably predict marital distress among parents of chronically ill children (Walker, Manion, Cloutier & Johnson, 1992). Cronbach’s alpha was high throughout the study period (.96 at Time 1, .96 at Time 2, and .97 at Time 3).

Parent–Child Conflict

The conflict subscale of the Parenting Questionnaire (Fauchier & Margolin, 2004) was used to assess parent–child conflict between the primary caregiver and the child with cancer via primary caregiver report. Six items assessing parent–child conflict in the past month (e.g., “I easily lose my temper with my child,” “My child and I disagree and quarrel”) were rated on a five-point scale and summed to form a total score, with higher scores indicating higher levels of conflict. Concurrent validity for this scale has been demonstrated by Fauchier and Margolin (2004) through comparison with the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (PCCTS), which has been validated for use with children ranging from infancy through adolescence (Straus, 2007). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable across time points (.82 at Time 1, .78 at Time 2, and .81 at Time 3).

Data Analytic Strategy

Cross-Lagged Models

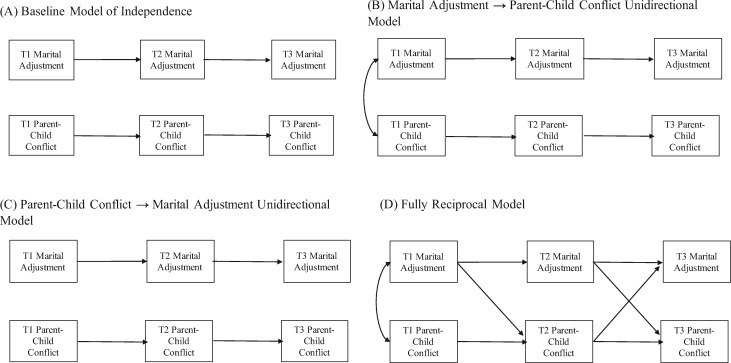

To test associations between marital and parent–child relationships, manifest variable cross-lagged models were used with each construct measured at three time points (see Figure 1 for full theoretical models). Cross-lagged models were selected because of their ability to test interrelations between constructs over time, and compare multiple directions of influence between dyads over time. Although cross-lagged models have faced some criticism in that they are not an appropriate method for assessing change within a construct over time (Rogosa, 1980), they are a useful tool for examining questions concerned with patterns of influence between constructs (Selig & Little, 2012). As such, they are appropriate for the current study. Models included the following paths: cross-lagged structural paths, whose regression coefficients reflect the extent to which one construct predicts another (i.e., X1 predicting Y2); autoregressive paths, which reflect stability in a single construct over time (i.e., X1 predicting X2); and estimates of residual covariance between exogenous constructs, which assesses whether changes in one variable not accounted for by the model are associated with concurrent changes in another. In other words, this assumes that two variables measured simultaneously share at least one unmeasured cause as a function of time (Kline, 2016). Autoregressive and cross-lagged paths are estimated controlling for the other, in other words testing whether one construct predicts change in another (i.e., X1 predicting Y2, controlling for Y1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical models for unidirectional vs. reciprocal nested model comparisons. See Table II for model fit and comparisons.

Missing Data

To account for missing data, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in R was used to estimate model parameters, supplemented with auxiliary correlates to improve estimation with missing data (Graham, 2003). Auxiliary correlates are variables included in the model that may account for missingness, though are not considered part of the substantive model. Correlates were selected using a data-driven approach, as follows: missingness across the study period was correlated with family demographic variables (e.g., child gender, number of children in family), treatment variables (e.g., treatment intensity, frequency of treatment events), and T1 variables representing initial levels of stress and family functioning after diagnosis (e.g., economic stress, parenting strain, sibling conflict). Any variable that was correlated with missingness at ± 0.1 or greater was selected as an auxiliary correlate (van Buuren et al., 1999). This resulted in four auxiliary correlates: number of children in the family, economic strain, frequency of parenting stress related to medical care, and sibling competitiveness. Using the spider method, these variables were (1) correlated with all exogenous variables (T1 marital adjustment and parent–child conflict), (2) correlated with residuals of all outcomes (T2 and T3 for both constructs), and (3) correlated with residuals of all other auxiliary correlates (Graham, 2003).

Testing the Research Questions

To test the first research question, four nested model comparisons were conducted to assess direction of spillover between family dyads—specifically, to compare models of unidirectional versus bidirectional influence (see Figure 1 for a depiction of each model). First, a baseline model of independence was established that included only autoregressive paths (no cross-lagged paths; Model A). This model suggests that each family dyad has no relation with the other over time, and was used as a basis for comparison for subsequent models positing different patterns of relations between dyads. Cross-lagged paths were then added to compare three models with the baseline model: (1) a model representing unidirectional spillover from marital adjustment to parent–child conflict over time (Model B); (2) a model representing unidirectional spillover from parent–child conflict to marital adjustment over time (Model C); and (3) a model representing spillover in both directions, in which all cross-lagged paths were included (Model D). Model D was also compared with both Models B and C to determine whether a model representing bidirectional influence fit better than either model fit representing unidirectional influence. Model fit comparisons were done via chi-square difference tests, comparisons of the root mean square error approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), and Aikaike information criteria (AIC). To address the second research question regarding how these relations specifically unfold over time, path coefficients were then interpreted from the best fitting model. To assess change in influence between constructs over time, path coefficients were not constrained.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Ms, SDs, and correlations for study variables are displayed in Table I. All correlations were in the expected directions. Results from independent samples t-tests or analysis of variances revealed no differences between any study variables based on recruitment site or demographic variables of diagnosis or child gender. Across all time points, mean marital adjustment scores were within the normal range (scored >107), though 16.2% of couples scored in the distressed range at Time 1, 15.4% at Time 2, and 8.5% at Time 3. However, few couples (<2%) were considered highly distressed (scored < 80) at any time point. Parent–child conflict ranged from 8.54 to 9.06, which corresponds with a low to average level on a scale ranging from 0 to 30. Because of substantial attrition, families with any missing data were compared with those with no missing data. Results suggested no differences between groups on gender, age of child, diagnosis, or initial parent–child conflict scores. Because marital adjustment at Time 1 was associated with number of missing data points (r = −.26, p = .01), initial marital adjustment was included as a predictor in all models.

Table I.

Observed Variable Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Marital Adjustment | – | ||||||

| 2. T2 Marital Adjustment | .72*** | – | |||||

| 3. T3 Marital Adjustment | .74*** | .80** | – | ||||

| 4. T1 Parent-Child Conflict | −.18 | −.16 | −.38** | – | |||

| 5. T2 Parent-Child Conflict | −.33** | −.33** | −.53** | .59*** | – | ||

| 6. T3 Parent-Child Conflict | −.24 | −.38** | −.33* | .41** | .74*** | – | |

| 7. Tx Intensity | −.05 | −.12 | −.14 | −.13 | .09 | .02 | – |

| N | 96 | 74 | 57 | 104 | 81 | 61 | |

| M | 123.26 | 122.87 | 125.75 | 8.54 | 9.06 | 8.82 | 2.56 |

| SD | 20.56 | 22.78 | 22.02 | 2.59 | 2.86 | 2.96 | 0.71 |

Note. N = 117. For marital adjustment, higher scores represent better adjustment. Scores ≤ 107 indicate marital distress. For parent-child conflict, higher scores represent more conflict. For treatment intensity, higher scores represent more intensive treatment. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Cross-Lagged Panel Models

Unidirectional Versus Bidirectional Patterns of Spillover

Nested model comparisons were used to test the hypothesis that a bidirectional rather than unidirectional relationship exists between marital adjustment and parent–child conflict during the first year of treatment. Results of each model and model fit comparisons are presented in Table II, and a graphical depiction of each model is presented in Figure 1. As predicted, based on comparisons of fit indices, the bidirectional model in which all autoregressive and reciprocal paths in both directions were included (Figure 1: Model D) had better fit compared with the baseline model (Figure 1: Model A), and the parent–child conflict to marital unidirectional model (Figure 1: Model C). Based on the chi-square difference test, the bidirectional model did not have significantly better fit compared with the marital adjustment to parent–child conflict unidirectional model (Figure 1: Model B). In addition, while the RMSEA value was slightly improved in the bidirectional model, comparing CFI and AIC fit indices also suggested no appreciable difference between models. Thus, it was concluded that the bidirectional model provided no appreciable improvement in fit, and the more parsimonious marital to parent–child unidirectional model was retained. In summary, model fit comparisons indicated partial support for our first hypothesis such that spillover does occur between the marital and parent–child relationships during the first year of treatment (as indicated by comparisons to the baseline model), though it is best characterized as unidirectional (from the marital to the parent–child relationship) rather than bidirectional.

Table II.

Model Fit and Fit Comparisons

| Model Fit Information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (df) | RMSEA | CFI | AIC | |

| A. Baseline | 18.18 (11) | .07 | 0.97 | 5628.4 |

| B. Marital → Parent-Child | 12.18 (9) | .05 | 0.99 | 5626.4 |

| C. Parent-Child → Marital | 13.46 (9) | .06 | 0.98 | 5627.7 |

| D. Bidirectional | 7.53 (7) | .02 | 0.99 | 5625.7 |

| Nested Model Fit Comparisons | ||||

| χ2dif (dfdif) | ||||

| A vs. B | 6.00 (2)* | |||

| A vs. C | 4.73 (2) | |||

| A vs. D | 10.65 (4)* | |||

| B vs. C | 1.28 (0)*** | |||

| B vs. D | 4.65 (2) | |||

| C vs. D | 5.93 (2)+ | |||

Note. +p = .05, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error Approximation; CFI = Comparative Fit Index. AIC = Aikake Information Criteria. Final model in bold.

Temporal Patterns of Spillover

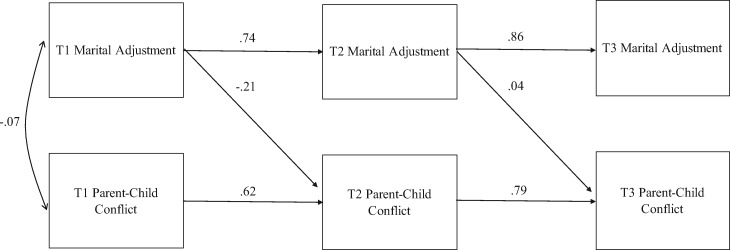

Path coefficients from the retained marital to parent–child unidirectional model were then interpreted to determine specific temporal patterns of spillover. This model showed good fit to the data, (χ2 (9) = 12.18, p = .20; CFI = .99; RMSEA = .05; see Figure 2). All first-order autoregressive paths were strong, as expected, meaning that previous levels of a construct predicted itself at later time points. Cross-lagged path estimates indicated that lower marital adjustment at T1 predicted higher parent–child conflict at T2 (ß = −.21, SE = .01, p = .01). No other cross-lagged paths were significant. Thus, the second hypothesis that marital adjustment drives patterns of spillover was supported such that poorer marital adjustment soon after diagnosis predicts an increase in parent–child conflict 6 months later.

Figure 2.

Final substantive model with standardized path estimates. χ2 (9) = 12.18, p =.12; CFI =.99; RMSEA =.05. Auxiliary correlates were included but are not depicted for clarity (see ‘Data Analytic Strategy’ section for more information).

Discussion

While some existing evidence suggests that some families experience conflict or strain in family relationships after a child’s cancer diagnosis, particularly within the marital relationship (Burns et al. 2017; Dahlquist et al, 1993; Katz et al., 2016), no studies to date have temporally examined how change in the marital relationship affects other family relationships in the context of cancer. The current study applied a spillover framework to the study of interrelations between family subsystems in families of children with cancer to test whether and how the marital and parent–child relationships influence one another during treatment and the direction and timing of such effects to inform intervention development.

Most couples in the current study scored in the happily married range (>107) at each time point, and parent–child conflict was low on average across time points given the range of the scale. Results suggested that spillover is occurring and it is driven by the marital relationship, as the model of unidirectional influence from the marital to the parent–child relationship best explained the data. This is aligned with most extant literature among families of non-ill children (for a review, see Erel & Burman, 1995), suggesting that quality of the marital relationships may influence conflict between parents and children both in typical contexts and in unique contexts such as pediatric cancer.

In terms of temporal patterns of spillover, results suggest that marital adjustment soon after diagnosis may spillover into the parent–child relationship in the first 6-months postdiagnosis. Specifically, lower marital adjustment during the first month postdiagnosis may be associated with an increase in parent–child conflict at 6 months. Interestingly, this pattern was not repeated between marital adjustment at 6 months and parent–child conflict at 12 months in the current study, suggesting that problems in the marriage soon after diagnosis may be uniquely indicative of later issues in family functioning. This highlights the importance of early identification of at-risk families and considering appropriate timing of intervention.

The effects of stress on the family may be one mechanism to explain spillover from the marital to the parent–child relationship in families of children with cancer. During treatment, families face numerous and prolonged stressors (McCaffrey, 2006), and coping resources of both parents and children are taxed. This may be especially pronounced around the time of diagnosis (Pai et al., 2007). Thus, for parents, marital quality may suffer in the face of stress (Sheeran, Marvin & Pianta, 1997), and this loss of a supportive partner may further exacerbate the effects of stress and make emotion regulation or coping more difficult (Gottman & Katz, 1989). Stressed parents may also be more likely to use ineffective parenting strategies, potentially leading to greater conflict with children (Webster-Stratton, 1990).

Results of this study suggest that quality of the marital relationship soon after a child’s cancer diagnosis may predict later family function. Intervention targeting marital relationships in early months after diagnosis may then be maximally effective in helping to minimize later problems in the parent–child relationship and potentially later exacerbation of marital conflict. Such interventions may be particularly beneficial to couples that report marital distress in the first months after diagnosis (Katz et al., 2016), though could also serve a preventative function by supporting happily married couples, as they navigate the myriad challenges inherent in cancer treatment. While parents may be reluctant to enroll in an intervention focused on marital adjustment immediately after their child’s diagnosis, brief interventions in the first few months of treatment may be viable. Indeed, enrollment was high in a recent pilot study of a brief resilience intervention for parents of children with cancer, with a median of 5 months since diagnosis at time of enrollment (Yi-Frazier et al., 2017). Additionally, screening for marital adjustment in the first few months postdiagnosis may aid in identifying at-risk families who could then be targeted for later intervention.

This study has strengths and limitations that may inform future work. First, families who were approached but did not enroll may have had poorer prognoses or more existing family stressors than those who did enroll, and thus may have had different patterns of spillover. Second, as observed rates of parent–child conflict were low, parents may be reluctant to report on conflict with their child with cancer which may have resulted in an underestimation of parent–child conflict. The measure used to assess parent–child conflict has also not been validated for use with pediatric samples. Third, because all measures were completed by the primary caregiver, there is risk of single-reporter bias. Stressed caregivers or those struggling with their own psychological adjustment may be more likely to notice or be more sensitive to problems in the marital relationship as well as conflict with the child. Use of multiple reporters or observational methods may address this issue in future work.

Finally, some limitations related to the quantitative methods used in the current study should be considered. Use of FIML as an estimation procedure assumes that any missing data are MAR (missing at random). While efforts were made in all models to account for missing data (e.g., inclusion of auxiliary correlate variables), data may have been MNAR (missing not at random) as suggested by the negative correlation between marital adjustment and missing data. If so, these may have resulted in biased estimates. Cross-lagged models also do not account for intraindividual change. As such, findings from the current study should not be used for inferences related to trajectories of change in these constructs over time (e.g., increases, decreases, or stability in marital adjustment). Strengths of this study include its prospective design and use of statistical methodology allowing for assessment of bidirectional effects rather than solely unidirectional processes. Finally, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine spillover between the marital and parent–child dyads in the context of pediatric cancer.

Given the well-established negative effects of family conflict on children’s adjustment, identifying appropriate, efficient, and effective ways to minimize conflict and preserve quality of family relationships during pediatric cancer treatment is needed. To do so, it is first necessary to understand when and with whom to intervene to aid prevention efforts and minimize burden on families. Based on results from the current study, the marital relationship may be the optimal point of intervention in early months postdiagnosis to prevent later spillover. In the context of cancer, the maintaining supportive and protective family relationships may serve to both support family members coping with the child’s diagnosis and ultimately protect the children from the deleterious effects of family conflict.

Funding

This research was supported by grant R01-CA134794 from the National Cancer Institute to the senior author.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Almeida D. M., Wethington E., Chandler A. L. (1999). Daily transmission of tensions between marital dyads and parent-child dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Burns W., Péloquin K., Sultan S., Moghrabi A., Marcoux S., Krajinovic M., Sinnett D., Laverdière C., Robaey P. (2017). A 2‐year dyadic longitudinal study of mothers' and fathers' marital adjustment when caring for a child with cancer. Psycho‐oncology, 26, 1660–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M. J., Paley B., Harter K. (2001). Interparental conflict and parent-child relationships In Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 249–272). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E. M., Davies P. T., Campbell S. B. (2000). Developmental psychopathology and family process: Theory, research, and clinical implications. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlquist L. M., Czyzewski D. I., Copeland K. G., Jones C. L., Taub E., Vaughan J. K. (1993). Parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer: Anxiety, coping, and marital distress. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 18, 365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P. T., Cummings E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 387–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engfer A. (1988). The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother-child relationship In Relationships within families: Mutual influences (pp. 104–118). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erel O., Burman B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 108–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauchier A., Margolin G. (2004). Affection and conflict in marital and parent-child relationships. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 30, 197–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fife B., Norton J., Groom G. (1987). The family's adaptation to childhood leukemia. Social Science and Medicine, 24, 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F. D., Grych J. H., Osborne L. N. (1994). Does marital conflict cause child maladjustment? Directions and challenges for longitudinal research. Journal of Family Psychology, 8, 128–140. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard J. M., Krishnakumar A., Buehler C. (2006). Marital conflict, parent-child relations, and youth maladjustment a longitudinal investigation of spillover effects. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 951–975. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman J. M., Katz L. F. (1989). Effects of marital discord on young children's peer interaction and health. Developmental Psychology, 25, 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. W. (2003). Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 10, 80–100. [Google Scholar]

- Grych J. H., Fincham F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 267–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J., Simpson A., Dunn J., Rasbash J., O'Connor T. G. (2005). Mutual influence of marital conflict and children's behavior problems: Shared and nonshared family risks. Child Development, 76, 24–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. F., Fladeboe K., Lavi I., King K. M., Kawamura J., Friedman D., Compas B., Breiger D., Lengua L., Gurtovenko K., Stettler N. (in press). Pediatric cancer and trajectories of marital adjustment, parent-child conflict, and sibling conflict. Health Psychology. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Katz L. F., Fladeboe K., Lavi I., King K., Kawamura J., Friedman D., Compas B., Breiger D., Lengua L., Gurtovenko K., Stettler N. (2016, October). Longitudinal patterns of marital, parent-child, and sibling conflict in the first year after a child's diagnosis of cancer. Presentation presented at the International Society of Paediatric Oncology, Dublin, Ireland.

- Katz L. F., Gottman J. M. (1993). Patterns of marital conflict predict children's internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 29, 940–950. [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. F., Gottman J. M. (1996). Spillover effects of marital conflict: In search of parenting and coparenting mechanisms. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1996, 57–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz L. F., Kramer L., Gottman J. M. (1992). Conflict and emotions in marital, sibling, and peer relationships In Cambridge studies in social and emotional development. Conflict in child and adolescent development (pp. 122–149). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. E., Hocking M. C., Ittenbach R. F., Meadows A. T., Hobbie W., DeRosa B. W., Leahey A., Kersun L., Reilly A. (2012). A revision of the intensity of treatment rating scale: Classifying the intensity of pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 59, 96–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Larson L. S., Wittrock D. A., Sandgren A. K. (1994). When a child is diagnosed with cancer: I. Sex differences in parental adjustment. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 12, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lavee Y. (2005). Correlates of change in marital relationships under stress: The case of childhood cancer. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 86, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal-Belfer L., Bakker A. M., Russo C. L. (1993). Parents of childhood cancer survivors: A descriptive look at their concerns and needs. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 11, 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Long K. A., Marsland A. L. (2011). Family adjustment to childhood cancer: A systematic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 57–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G., Christensen A., John R. S. (1996). The continuance and spillover of everyday tensions in distressed and nondistressed families. Journal of Family Psychology, 10, 304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Marine S., Miller D. (1998). Social support, social conflict, and adjustment among adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 23, 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey C. N. (2006). Major stressors and their effects on the well-being of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 21, 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai A. L., Greenley R. N., Lewandowski A., Drotar D., Youngstrom E., Peterson C. C. (2007). A meta-analytic review of the influence of pediatric cancer on parent and family functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 407–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D. (1980). A critique of cross-lagged correlation. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Sears M. S., Repetti R. L., Reynolds B. M., Robles T. F., Krull J. L. (2016). Spillover in the home: The effects of family conflict on parents' behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 127–141. [Google Scholar]

- Selig T., Little J. P. (2012). Autoregressive and cross-lagged panel analysis for longitudinal data In Handbook of developmental research methods (pp. 265–278). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran T., Marvin R. S., Pianta R. (1997). Mothers' resolution of their child's diagnosis and self-reported measures of parenting stress, marital relations, and social support. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22, 197–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier G. B. (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A. (2007). Conflict tactics scales In Encyclopedia of domestic violence (pp. 190–197). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S., Boshuizen H. C., Knook D. L. (1999). Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoors M., Caes L., Alderfer M. A., Goubert L., Verhofstadt L. (2017). Couple functioning after pediatric cancer diagnosis: A systematic review. Psycho-oncology, 26, 608–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoors M., Caes L., Knoble N. B., Goubert L., Verhofstadt L. L., Alderfer M. A. (2017). Systematic review: Associations between family functioning and child adjustment after pediatric cancer diagnosis: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42, 6–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schoors M., Caes L., Verhofstadt L. L., Goubert L., Alderfer M. A. (2015). Systematic review: Family resilience after pediatric cancer diagnosis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 40, 856–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderValk I., De Goede M., Spruijt E., Meeus W. (2007). A longitudinal study on transactional relations between parental marital distress and adolescent emotional adjustment. Adolescence, 42, 115–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker J., Manion I., Cloutier P., Johnson S. (1992). Measuring marital distress in couples with chronically ill children: The dyadic adjustment scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 17, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. (1990). Stress: A potential disruptor of parent perceptions and family interactions. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 19, 302–312. [Google Scholar]

- Wood N. D., Crane D. R., Schaalje G. B., Law D. D. (2005). What works for whom: A meta-analytic review of marital and couples therapy in reference to marital distress. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 33, 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Yi-Frazier J. P., Fladeboe K., Klein V., Eaton L., Wharton C., McCauley E., Rosenberg A. R. (2017). Promoting resilience in stress management for parents (PRISM-P): An intervention for caregivers of youth with serious illness. Families, Systems and Health, 35, 341–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]