This analysis of health claims data from 3 large nationwide insurers examines changes in oral anticancer medication use, out-of-pocket spending, and total health plan spending associated with adoption of state parity laws.

Key Points

Question

How have state parity laws regarding coverage for orally administered chemotherapy drugs changed their use, out-of-pocket spending, and total health plan expenses?

Findings

In this analysis of health claims data from 3 nationwide insurers involving 63 780 adults, state parity laws appeared to reduce monthly spending on prescription fills at the lower end of the out-of-pocket spending distribution but appeared to increase spending for prescription fills with the highest out-of-pocket spending. Parity laws were not associated with changes in 6-month total health care spending.

Meaning

Although oral chemotherapy parity laws have been widely adopted by states, these laws have not consistently reduced out-of-pocket spending for orally administered anticancer medications.

Abstract

Importance

Oral anticancer medications are increasingly important but costly treatment options for patients with cancer. By early 2017, 43 states and Washington, DC, had passed laws to ensure patients with private insurance enrolled in fully insured health plans pay no more for anticancer medications administered by mouth than anticancer medications administered by infusion. Federal legislation regarding this issue is currently pending. Despite their rapid acceptance, the changes associated with state adoption of oral chemotherapy parity laws have not been described.

Objective

To estimate changes in oral anticancer medication use, out-of-pocket spending, and health plan spending associated with oral chemotherapy parity law adoption.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Analysis of administrative health plan claims data from 2008-2012 for 3 large nationwide insurers aggregated by the Health Care Cost Institute. Data analysis was first completed in 2015 and updated in 2017. The study population included 63 780 adults living in 1 of 16 states that passed parity laws during the study period and who received anticancer drug treatment for which orally administered treatment options were available. Study analysis used a difference-in-differences approach.

Exposures

Time period before and after adoption of state parity laws, controlling for whether the patient was enrolled in a plan subject to parity (fully insured) or not (self-funded, exempt via the Employee Retirement Income Security Act).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Oral anticancer medication use, out-of-pocket spending, and total health care spending.

Results

Of the 63 780 adults aged 18 through 64 years, 51.4% participated in fully insured plans and 48.6% in self-funded plans (57.2% were women; 76.8% were aged 45 to 64 years). The use of oral anticancer medication treatment as a proportion of all anticancer treatment increased from 18% to 22% (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; P = .34) comparing months before vs after parity. In plans subject to parity laws, the proportion of prescription fills for orally administered therapy without copayment increased from 15.0% to 53.0%, more than double the increase (12.3%-18.0%) in plans not subject to parity (P < .001). The proportion of patients with out-of-pocket spending of more than $100 per month increased from 8.4% to 11.1% compared with a slight decline from 12.0% to 11.7% in plans not subject to parity (P = .004). In plans subject to parity laws, estimated monthly out-of-pocket spending decreased by $19.44 at the 25th percentile, by $32.13 at the 50th percentile, and by $10.83 at the 75th percentile but increased at the 90th ($37.19) and 95th ($143.25) percentiles after parity (all P < .001, controlling for changes in plans not subject to parity). Parity laws did not increase 6-month total spending for users of any anticancer therapy or for users of oral anticancer therapy alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

While oral chemotherapy parity laws modestly improved financial protection for many patients without increasing total health care spending, these laws alone may be insufficient to ensure that patients are protected from high out-of-pocket medication costs.

Introduction

Orally administered anticancer medications are an increasingly important part of cancer treatment. By mid-2015, there were more than 50 orally administered anticancer medications approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, with more medications anticipated in coming years. These medications are expensive, with list prices often exceeding $100 000 per year.1,2

Proponents of legislation aimed at limiting out-of-pocket expenditures for patients suggest that anticancer medications obtained under a patient’s pharmacy benefit can require higher enrollee cost sharing than infused medications covered under the medical benefit,3 potentially affecting patient access to outpatient prescriptions.4,5,6,7 In response, since 2008, 43 states and Washington, DC, have passed oral chemotherapy parity laws to ensure cost-sharing equality for oral and infused anticancer medications.8 These laws are intended to ensure that cost sharing (eg, copayments, coinsurance, or benefit limits) for patients is equivalent for anticancer drugs obtained with either medical (infused) or pharmacy (oral) benefits. Despite their rapid acceptance, the association of the state oral chemotherapy parity laws with oral anticancer medication use and patient and health care spending is unknown.

Methods

We used 2008-2012 national administrative health plan claims from the Health Care Cost Institute for privately insured members of Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare to estimate the association of oral chemotherapy parity laws with the use of orally administered anticancer drugs and their out-of-pocket spending. Original analysis of data was completed in 2015; revisions were updated in 2017. We studied 72 500 patients aged 18 through 64 years who had prescription drug coverage; lived in 16 states implementing parity laws between July 1, 2008, through July 15, 2012; were treated with infused or orally administered anticancer medication; and were assigned diagnosis codes for a cancer for which orally administered drugs were available. We excluded 6104 individuals without 3 months of continuous health plan enrollment before the observation month (for comorbidity measurement) and 2616 individuals missing insurance plan funding status. In total, 63 780 individuals with 375 387 person-months of anticancer medication use were included. This study received an exemption from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Review Board.

We identified infused anticancer therapy from outpatient and physician service claims and orally administered anticancer medications from pharmacy claims. As in previous work by others,9,10 we included targeted orally administered anticancer medications and capecitabine (which has an infused equivalent) but excluded breast cancer endocrine therapies (eMethods 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement). We measured oral anticancer therapy use as a proportion of all anticancer therapy provided in each person-month.

We summarized out-of-pocket spending per prescription fill on oral anticancer medications, including copayment, coinsurance, and deductibles, adjusting to reflect spending on a median monthly dosage. We also summarized 6-month total health care spending beginning with the patient’s first observed anticancer therapy.11

Statistical Analysis

We used a propensity score–weighted, difference-in-differences approach to estimate the net association of parity with the use of orally administered anticancer drugs and out-of-pocket spending among individuals in fully insured plans, controlling for changes over time among individuals in self-funded plans (not subject to parity laws via the Employee Retirement Income Security Act [ERISA]) in those states.12 A 2-sided t test was used, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Our 3 models with binary outcomes included the probability of (1) using oral anticancer medications, (2) paying $0 per month for orally administered anticancer medications, and (3) paying more than $100 per month for orally administered anticancer medications. We used generalized estimating equations with logarithmic links and binomial distributions to account for repeated observations.13 As a result of parity laws, we observed nonlinear changes in out-of-pocket spending and used quantile regression to estimate changes at the 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles of monthly out-of-pocket spending.14,15 Finally, for 6-month total health care spending, we used generalized estimating equations with logarithmic links and gamma distributions and retransformed model estimates to 2012 US dollars. Data analyses were performed with PROC QUANTREG and PROC GENMOD in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). For further model descriptions and sensitivity analyses, see eMethods 2 in the Supplement.

Results

Of 63 780 individuals aged 18 to 64 years and using anticancer medications in states that passed parity laws during the study period, 51.4% participated in fully insured plans and 48.6% in self-funded plans (57.2% were women; 76.8% were aged 45-65 years). After propensity score weighting, patients were well balanced on measured characteristics (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Oral anticancer medication use as a proportion of all anticancer medication use increased from approximately 18% to 22%, with no significant differences attributed to parity laws (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 1.04; 95% CI, 0.96-1.13; P = .34).

In both fully insured and self-funded health plans, monthly out-of-pocket spending was $50 or less for most prescription fills of orally administered and infused anticancer medications both before and after parity laws (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement). After parity laws, the probability of paying $0 per month for orally administered anticancer medications more than doubled in fully insured plans (from 15.0% to 53.0%) compared with self-funded plans (from 12.3% to 18.0%) (aDDRR, 2.36; 95% CI, 2.00-2.79; P < .001). However, there was an increase in the proportion of prescription fills with out-of-pocket spending of more than $100 per month in fully insured plans (from 8.4% to 11.1%) vs self-funded plans (from 12.0% to 11.7%) during the same period (aDDRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11-1.68; P = .004). Among infused treatments, there was no difference in the probability of paying $0 per month (aDDRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.10; P > .05) or the probability of paying more than $100 per month (aDDRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.79-1.39; P > .05).

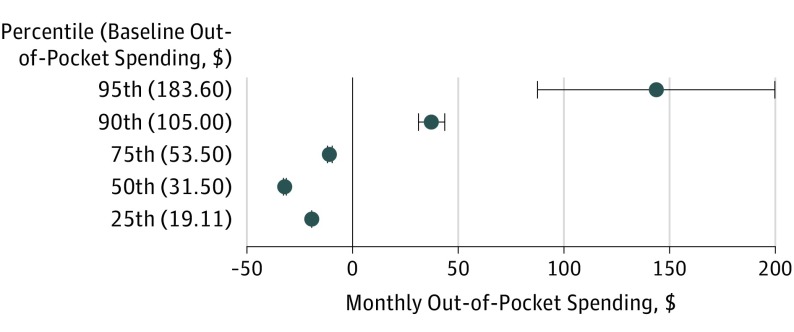

When considering the distribution of spending, the adoption of state parity laws was associated with modest but statistically significant decreases in estimated monthly out-of-pocket spending on orally administered anticancer medications by $19.44 at the 25th percentile, $32.13 at the 50th, and $10.83 at the 75th (all P < .001, controlling for changes in plans not subject to parity during the same period). However, spending increased by $37.19 at the 90th percentile and $143.25 at the 95th (all P < .001; Figure 1 and eTable 3). In a sensitivity analysis that excluded deductibles, results were consistent, but out-of-pocket spending increases of $24.32 (90th percentile) and $49.43 (95th percentile) were somewhat lower and not statistically significant for the 95th percentile.

Figure 1. Association of Parity Laws With Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending for Orally Administered Anticancer Medications.

Data represent quantile regression analyses of Health Care Cost Institute claims, 2008-2012 (85 107 observations), in propensity-weighted cohorts to estimate changes in the distribution of patient out-of-pocket spending on a single prescription fill of orally administered anticancer therapy. Medication costs per prescription fill were adjusted to reflect a standardized dosage of therapy, and dollars were inflation adjusted to 2012 US dollars by using the medical component of the US Consumer Price Index. Models were estimated using PROC QUANTREG in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Values in parentheses represent baseline spending per prescription fill for each percentile; data markers show the mean change in spending after parity at the specified point on the distribution; error bars, 95% CIs.

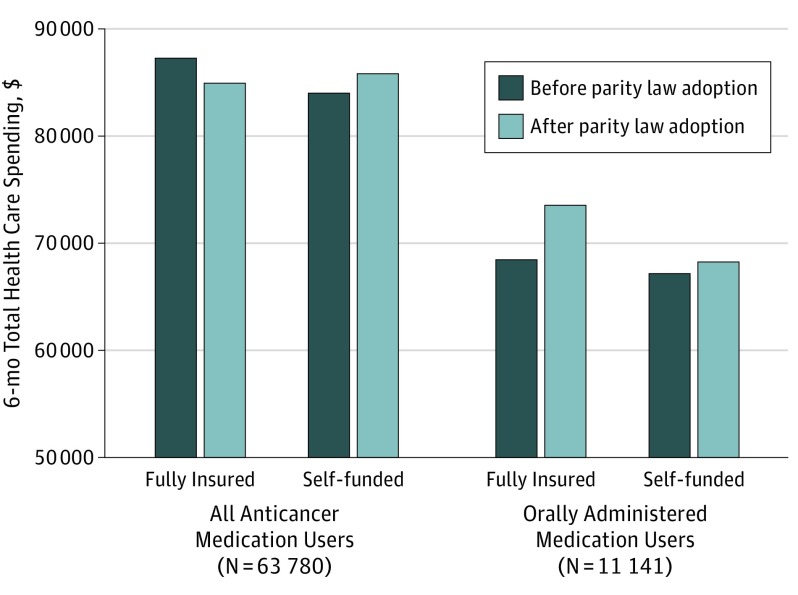

Before parity, total health care spending for 6-month treatment episodes of all anticancer medication users were a mean of $87 328 (95% CI, $85 481-$89 214) for patients in fully insured plans and $84 103 (95% CI, $82 524-$85 712) for patients in self-funded plans (Figure 2). There were no statistically significant changes in spending by parity status (for all anticancer medication users, P = .09; for oral anticancer medication users, P = .40).

Figure 2. Association of Parity Laws With 6-Month Total Health Care Spending.

Data represent an analysis of Health Care Cost Institute claims, 2008-2012. Propensity score–weighted, generalized estimating equations with logarithmic links and gamma distributions were used to estimate 6-month spending on health care services. Models were estimated using PROC GENMOD in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). There were no significant differences in total health care spending as a result of parity laws adoption for all anticancer medication users (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 0.96; 95% CI, 0.90-1.02; P = .09) or for orally administered anticancer medication users (aDDRR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.93-1.20; P = .40).

Discussion

Although oral chemotherapy parity laws have been widely adopted by states, these laws have not consistently reduced out-of-pocket spending for orally administered anticancer medications. Specifically, parity laws reduced monthly out-of-pocket spending on prescription fills at the lower end of the spending distribution but increased spending for prescription fills at the highest end of the spending distribution. Medication fills with $0 per month cost sharing more than doubled, and costs simultaneously increased for medication fills with at least $100 per month in cost sharing after adoption of parity laws.

Our findings illuminate several important issues for privately insured patients. First, plans typically required relatively modest cost sharing before and after parity laws (<$50/mo). However, approximately 5% of prescription fills had out-of-pocket spending of $500 or more in fully insured plans after parity laws, suggesting that parity law requirements alone may not address high out-of-pocket spending for some patients. Second, estimated out-of-pocket spending did not change for patients in self-funded plans, which are exempt from state mandates. Federal legislation would be required to extend parity laws to individuals in self-funded plans. Finally, opposition to state efforts have centered on concerns that improved coverage for orally administered chemotherapy would increase overall health care spending, but we found no evidence of increases from our 6-month health care spending results.

Limitations

This study has some important limitations. First, we studied 16 states that passed parity laws from 2008 to 2012; thus, our findings may not represent all states with parity laws from more recent time periods. However, parity laws passed more recently are nearly identical to those in the 16 states studied.8 Second, we could not observe drug manufacturer coupon use or patients who do not fill their prescriptions because of very high cost sharing for their anticancer medication. Third, we studied patients in 3 health plans; thus results may not generalize to other insurers. However, Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare are among the largest private insurers in the United States. Finally, all orally administered anticancer medications were branded products, and out-of-pocket spending requirements may differ for generic or biosimilar medications.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that, while state oral chemotherapy parity laws modestly improved financial protection for many patients without increasing total health care spending, these laws alone may be insufficient to ensure that patients are protected from high out-of-pocket costs.

eMethods 1. Anticancer Medication Selection

eMethods 2. Difference-in-Differences Estimation

eTable 1. High-Cost Oral Cancer Medications and FDA-Approved Cancer Indications

eTable 2. Characteristics of Anticancer Medication Users by Plan Funding Status Before and After Propensity Weighting

eTable 3. Changes in Out-of-Pocket Spending for Orally Administered Anticancer Medications – Full Difference-in-Differences Model Results

eFigure 1. Estimated Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending on Anticancer Medications Before and After Parity, by Plan Funding Status

eFigure 2. Histogram of Logged Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending by Plan Funding and Time

References

- 1.Bach PB. Monthly and median costs of cancer drugs at the time of FDA approval 1965-2016. https://www.mskcc.org/research-areas/programs-centers/health-policy-outcomes/cost-drugs. Accessed October 2, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dusetzina SB. Drug pricing trends for orally administered anticancer medications reimbursed by commercial health plans, 2000-2014. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews M. Some states mandate better coverage of oral cancer drugs. http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/features/insuring-your-health/2012/cancer-drugs-by-pill-instead-of-iv-michelle-andrews-051512.aspx. Accessed September 18, 2013.

- 4.Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, Johnsrud M. Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3)(suppl):46s-51s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, Huskamp HA, Keating NL. Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4):306-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608-1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winn AN, Keating NL, Dusetzina SB. Factors associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor initiation and adherence among Medicare beneficiaries with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4323-4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B, Joffe S, Kesselheim AS. Chemotherapy parity laws: a remedy for high drug costs? JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1721-1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute targeted cancer therapies. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/targeted-therapies/targeted-therapies-fact-sheet. Published 2016. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- 10.Shih YC, Smieliauskas F, Geynisman DM, Kelly RJ, Smith TJ. Trends in the cost and use of targeted cancer therapies for the privately insured nonelderly: 2001 to 2011. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(19):2190-2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid innovation oncology care model. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2016. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 12.Wooldridge JM. What’s new in econometrics? difference-in-differences estimation. http://www.nber.org/WNE/lect_10_diffindiffs.pdf. Accessed October 2, 2017.

- 13.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckman JJ, Smith J, Clements N. Making the most out of programme evaluations and social experiments: accounting for heterogeneity in programme impacts. Rev Econ Stud. 1997;64(4):487-535. doi: 10.2307/2971729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckman JJ. The scientific model of causality. Sociol Methodol. 2005;35:1-97. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2006.00164.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Anticancer Medication Selection

eMethods 2. Difference-in-Differences Estimation

eTable 1. High-Cost Oral Cancer Medications and FDA-Approved Cancer Indications

eTable 2. Characteristics of Anticancer Medication Users by Plan Funding Status Before and After Propensity Weighting

eTable 3. Changes in Out-of-Pocket Spending for Orally Administered Anticancer Medications – Full Difference-in-Differences Model Results

eFigure 1. Estimated Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending on Anticancer Medications Before and After Parity, by Plan Funding Status

eFigure 2. Histogram of Logged Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending by Plan Funding and Time