Abstract

Background Renal glomeruli are the primary target of injury in diabetic nephropathy (DN), and the glomerular podocyte has a key role in disease progression.

Methods To identify potential novel therapeutic targets for DN, we performed high-throughput molecular profiling of G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) using human glomeruli.

Results We identified an orphan GPCR, Gprc5a, as a highly podocyte-specific gene, the expression of which was significantly downregulated in glomeruli of patients with DN compared with those without DN. Inactivation of Gprc5a in mice resulted in thickening of the glomerular basement membrane and activation of mesangial cells, which are two hallmark features of DN in humans. Compared with wild-type mice, Gprc5a-deficient animals demonstrated increased albuminuria and more severe histologic changes after induction of diabetes with streptozotocin. Mechanistically, Gprc5a modulated TGF-β signaling and activation of the EGF receptor in cultured podocytes.

Conclusions Gprc5a has an important role in the pathogenesis of DN, and further study of the podocyte-specific signaling activity of this protein is warranted.

Keywords: podocyte, diabetic nephropathy, TGF-beta, EGFR

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) develops in 20%–40% of patients with diabetes mellitus.1 The disease is responsible for >40% of new ESRD cases.2 Today the treatment options of DN are based largely on repurposing of existing therapeutics and are neither kidney-target–based nor designed to address the underlying molecular mechanisms. Obviously, it is important to develop more kidney-specific treatment modalities. However, we still understand rather poorly pathogenic mechanisms of diabetic renal damage and therefore lack distinct molecular targets.

DN is a microvascular complication of diabetes that affects primarily renal glomeruli.2 The hallmark sign of the disease is albuminuria secondary to glomerular damage. Glomerular pathology includes thickening of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), mesangial cell activation with expansion of mesangial matrix, and dedifferentiation and loss of podocyte cells.2 Glomerular damage leads eventually to sclerosis and decreased renal function. Signaling pathway mediated by TGF-β has been pinpointed to play a major role in the pathogenesis of glomerular disease.1 However, mechanisms modulating the pathway in DN are not well understood.

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute a protein family of receptors that sense molecules outside the cell and activate a great diversity of intracellular signal transduction pathways.3 Because of their central involvement in biologic processes, GPCRs have been a very successful protein class for drug discovery because the market share of drugs targeting GPCRs is 20%–30%.3

Because the glomerulus is the main target of injury in DN, we analyzed glomerular GPCRs by large-scale expressional profiling. We identified Gprc5a as a novel highly podocyte-specific GPCR whose expression was significantly downregulated in patients with DN. Studies in Gprc5a-deficient mouse line and cell culture indicate that the receptor modulates EGF receptor (EGFR) and TGF-β signaling in podocytes. Gprc5a knockout mice phenocopy key features of glomerular pathology in human DN, including the thickening of the GBM and mesangial cell activation. Moreover, Gprc5a deficiency in mice promotes the progression of nephropathy in diabetes, highlighting its central role in the pathogenesis of the disease. Gprc5a enables manipulation of pathogenic signaling pathways in a podocyte-specific fashion and can therefore be a new pharmaceutic target to treat DN.

Methods

Human Kidney Tissues

Control tissue was collected from kidneys removed due to renal carcinoma or from living kidney donors (Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden). Renal biopsy samples from patients with diabetes showing DN were collected from Karolinska University Hospital.

PCR Experiments

Glomeruli were isolated using standard sieving and perfusion protocols. The expression of human GPCRs was analyzed using a predesigned 384-well plate (GPCR Tier 1–4 H384; Bio-Rad) and Gapdh was used for normalization. Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 6. Relative mRNA levels of genes were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

Western Blotting, Immunostaining, and Immunoelectron Microscopy

Western blotting and immunohistochemical experiments were performed as previously described.4–7

Mouse Models

Gprc5a mutant mouse in FVB background was generated using TALENs (Cyagen). Inactivation of Gprc5a was verified using western blotting and RT-PCR. Diabetes was induced in 8-week-old littermate and mutant mice by intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (50 mg/kg) for 5 days. Induction of hyperglycemia was confirmed by measuring nonfasting blood glucose 2 weeks after the last injection and by analyzing HbA1c at the end of the experiment. Urine was collected every second week and mice were euthanized 24 weeks after injections.

Cell Culture

Immortalized human podocytes were grown as described.8 Stable overexpressing cells were established by transfecting pcDNA3.1-hGprc5a construct using Lipofectamine. Silencing of Gprc5a expression was done using siRNA (Invitrogen). Effects of Gprc5a on EGF-mediated signaling were studied by adding 25 ng/ml of HB-EGF on culture media.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

Effects of Gprc5a on Smad2/3-mediated target gene transcription were assessed further using a dual-luciferase reporter system (Promega).

Statistical Methods

Real-time PCR experiments were analyzed using t test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Immunohistochemical and morphologic data were analyzed using t test.

Results

High-Throughput Expressional Profiling of Isolated Human Glomeruli Reveals a Number of Novel Glomerulus-Enriched GPCRs

Because GPCRs have been an outstanding protein family to target pharmacologically, we performed a large-scale qPCR analysis of the glomerular GPCR transcriptome using a predesigned 384-well panel. The analysis of isolated human glomeruli revealed a number of GPCRs that were putatively enriched in the glomerulus as compared with the kidney fraction devoid of glomeruli (Supplemental Table 1). We identified several GPCRs known to be associated with glomeruli, such as PTGER4 (PG E receptor 4)9 and EDNRB (Endothelin receptor type B),10 but also several targets that have previously not been described to be present in the glomerulus. The Human Protein Atlas (www.proteinatlas.com) was used to confirm the glomerular protein expression of some the identified gene transcripts with highest expression (ELTD1, GPR160, F2R, S1PR1, CD97; Supplemental Figure 1) but still many genes remain to be confirmed by alternative methodologies. Among the identified genes, we focused on an orphan GPCR, Gprc5a, because it has not previously been ascribed a role in kidney function.

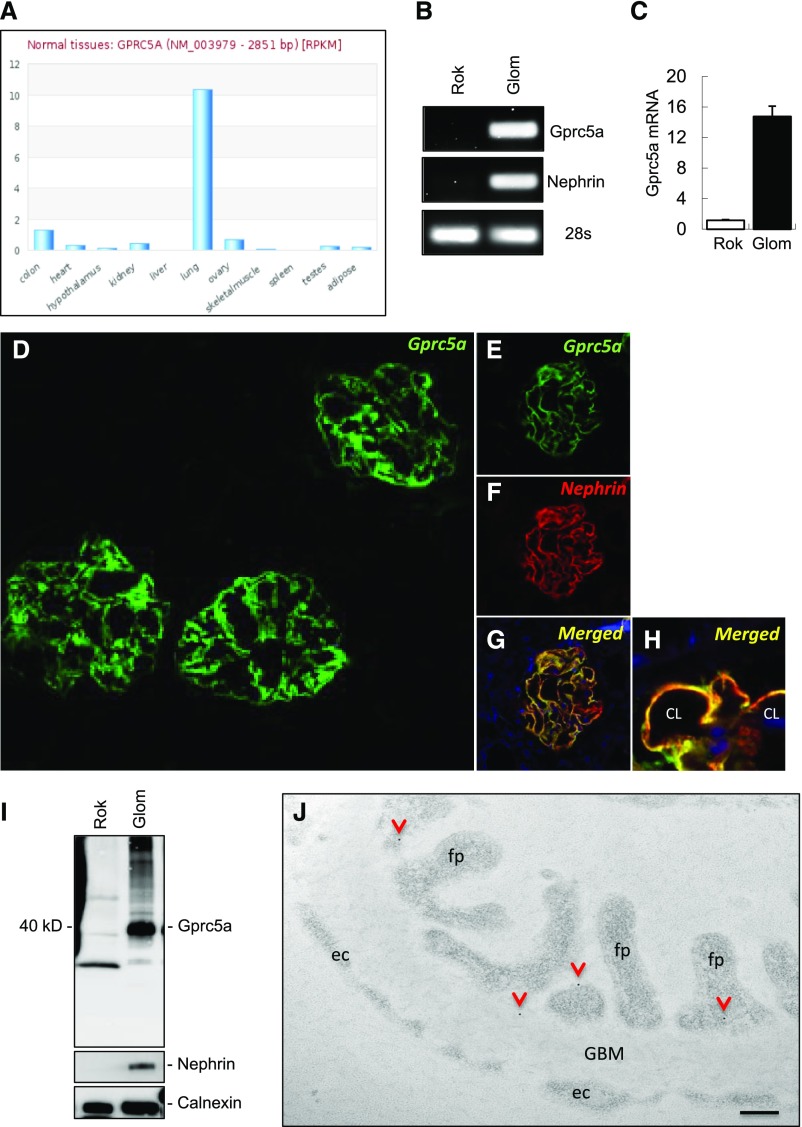

Gprc5a Is Highly Specific to Glomerular Podocytes

Expression of Gprc5a in different human tissues was studied by analyzing two publicly available RNA sequencing databases (www.medicalgenomics.org, www.proteinatlas.org). Both databases showed that Gprc5a was highly enriched in lung tissue and only sparsely expressed in other organs (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure 2A). In line with this, the RT-PCR experiment in RNA isolated from different mouse organs showed highly restricted and lung-enriched expression pattern (Supplemental Figure 2B). However, when we performed PCR using isolated kidney fractions, we could amplify a band for Gprc5a that was restricted to the human and mouse glomerulus (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 2B). This was confirmed by qPCR that showed 16-fold upregulation of the transcript in the glomerulus in comparison to the rest of the kidney (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Gprc5a is highly enriched in renal podocyte cells in humans. (A) Gprc5a transcript is highly expressed by lung tissue and only sparsely by other human tissues as detected by RNAseq analysis (data extracted from www.medicalgenomics.org). (B and C) In isolated human kidney fractions, RT-PCR and qPCR show Gprc5a expression in the glomerulus (Glom) and not in the fraction lacking glomeruli (Rok, rest of kidney). Nephrin was used to control the purity of glomerular fractions and 28S as a loading control. (D) Immunofluorescence for Gprc5a in adult human kidney tissue demonstrates strong immunoreactivity in glomeruli and no significant signal is detected in extraglomerular areas. (E–H) Double labeling with podocyte marker nephrin (red) shows almost complete overlapping (yellow) with Gprc5a (green) indicating localization to podocyte foot processes. (I) In western blotting, anti-Gprc5a antibody detects a 40-kD protein almost solely in the glomerulus fraction. Nephrin antibody validates the purity of isolated glomeruli and calnexin was used as a loading control (CL, capillary lumen). (J) Immunoelectron microscopy for Gprc5a shows gold labeling mostly in podocytes where it often localizes (arrowheads) close to the plasma membrane (fp, foot process; ec, endothelial cell). Original magnifications, ×150 (D); ×400 (F–H). (I) Scale bar=200 nm.

Next, we validated the expression of Gprc5a at the protein level. In immunofluorescence staining, a strong signal for Gprc5a was detected in human glomeruli whereas no reactivity was detected outside glomerular tufts (Figure 1D). In double labeling experiments Gprc5a showed almost complete overlapping reactivity with podocyte foot process marker nephrin (Figure 1, E–H). In western blotting, we detected a strong band sized approximately 40 kD in human glomeruli that was not readily detected in the tubulo-interstitial fraction devoid of glomeruli (Figure 1I). No expression was detected in glomerular endothelial or mesangial cells as shown by double labeling experiments with endothelial marker CD31 and mesangial marker PDGF receptor β (PDGFRB) (Supplemental Figure 3A).

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed to localize Gprc5a in more detail in podocytes. Immuno-gold label was detected mostly at the plasma membrane of podocytes (Figure 1J). No significant labeling was observed outside podocytes (Figure 1J, Supplemental Figure 3B). This was validated with a semiquantification of gold labeling (Supplemental Figure 3C). Taken together, our detailed molecular profiling unraveled Gprc5a as a novel highly podocyte-specific GPCR.

The specificity of anti-Gprc5a antibody was validated by transfecting HEK293 cells with a Gprc5a construct. Western blotting showed a clear band of about 40 kD in transfected cells whereas control cells showed no reactivity (Supplemental Figure 3D). Moreover, we used an additional Gprc5a antibody that was directed against a different part of Gprc5a protein.11 This antibody gave nearly an identical staining pattern in kidney tissue as the first antibody (Supplemental Figure 3E).

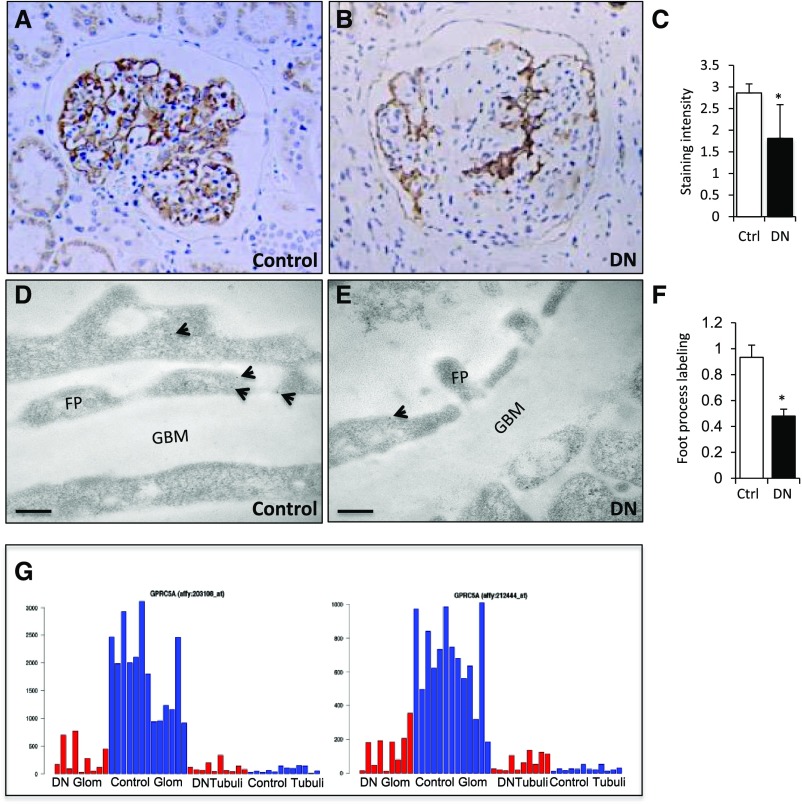

Gprc5a Expression Is Downregulated in DN

To study whether Gprc5a plays a role in human glomerular diseases, we analyzed its expression in biopsy samples collected from patients with DN. Clinical parameters of patients included are found in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. We detected a clearly reduced Gprc5a expression in DN glomeruli by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2, A and B). This was validated by a semiquantitative scoring of glomerular staining intensity (Figure 2C). Because podocytes can be lost in advanced stages of DN, we performed a semiquantitative immunoelectron microscopy study in which we analyzed Gprc5a expression in remaining podocytes. This analysis showed significantly decreased labeling for Gprc5a protein in DN (Figure 2, D–F).

Figure 2.

Gprc5a expression in the glomerulus is downregulated in patients with DN. (A and B) Immunohistochemistry in paraffin-embedded kidney biopsy samples shows clearly reduced glomerular staining in patients with DN in comparison to controls. (C) Visual scoring of staining intensity shows significant downregulation of Gprc5a expression. (D and E) Immunoelectron microscopy shows less gold labeling for Gprc5a in podocytes of patients with DN. (F) Semiquantification validates the reduced labeling intensity. (G) RNA levels of Gprc5a are significantly reduced in microdissected DN glomeruli in comparison to controls as detected by microarray using two different probes (left and right). No significant expression is detected in tubular fractions. Red, DN; blue, control. (A and B) Original magnifications, ×200. (D and E) Scale bars=150 nm. (C and F) Data shown as the mean±SEM; *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Ctrl, control; FP, foot process; Glo; glomerulus.

To analyze Gprc5a mRNA levels in DN glomeruli, we first analyzed our unpublished RNA sequencing dataset generated from microdissected glomeruli. The expression of Gprc5a mRNA was significantly reduced in isolated glomeruli of 20 patients with DN when compared with 20 control patients (A. Levin et al., manuscript under preparation). Finally, we analyzed data previously generated by Woroniecka et al.12 in which they performed microarray on glomerular tufts isolated from healthy patients and patients with DN. In the study, Gprc5a was one of the most highly downregulated genes in DN glomeruli (Figure 2G). Taken together, Gprc5a expression in glomeruli is significantly downregulated in patients with DN, suggesting a role in the disease process.

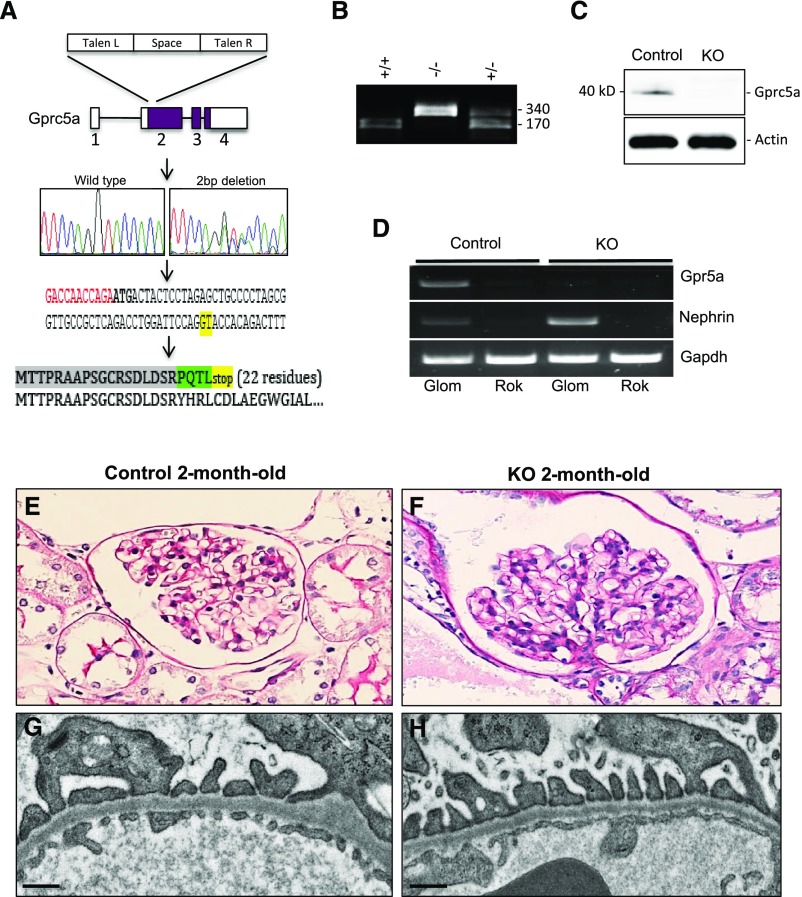

Generation and Characterization of Gprc5a Knockout Mouse Line

To analyze the role of Gprc5a in the glomerulus in vivo, we generated a mouse line in which Gprc5a gene was mutated. We targeted the first coding exon of Gprc5a gene using TALENs and mutagenesis generated a 2-bp deletion as validated by Sanger sequencing (Figure 3A). The coding sequence is predicted to go out of frame due to the deletion and produce a short 22-residue protein sequence.

Figure 3.

Mutant mice do not express Gprc5a and do not show any obvious renal phenotype at young age. (A) TALENs were used to generate a 2-bp deletion in exon 2 of Gprc5a gene (marked with green in DNA sequence). The gene goes out of frame and is predicted to generate a short 22-residue truncated protein. (B) Genotyping of Gprc5a mice. Wild-type mice show 170 bp, homozygous mutant 340 bp, and heterozygotes both fragments. (C and D) Mutation generates a null allele because no Gprc5a protein or mRNA is detected in mutant animals. (E and F) Kidney histology is normal in 2-month-old −/− animals as demonstrated by PAS staining. (G and H) In electron microscopy, no abnormalities are detected in glomerular endothelial cells, the GBM, or podocytes. (E and F) Original magnifications, ×200. (G and H) Scale bars=250 nm. KO, knockout; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff staining; TALEN, transcription activator-like effector nuclease.

The genotyping of Gprc5a mouse line was performed by amplifying a 340-bp product from the genomic region around the mutation followed by digestion with Kpn1 restriction enzyme. The wild-type allele generates two 170-bp fragments, whereas mutated animals lack the restriction site and generate an intact 340-bp fragment (Figure 3B). As expected, the mutation generates a null allele because no Gprc5a protein was detected using western blotting (Figure 3C). Moreover, the mutation seems to result in an instable mRNA because no Gprc5a transcript could be amplified using RT-PCR (Figure 3D). Taken together, we generated successfully a Gprc5a-deficient mouse line (−/−).

Knockout mice were born in an expected Mendelian heritance, developed normally, and did not exhibit any obvious macroscopic or histologic abnormalities in major organs (data not shown). Renal histology was normal at birth and at 2 months of age as observed in routine light and electron microscopic examination (Figure 3, E–H). The glomerular filtration barrier seemed to be also functionally intact because no albuminuria was detected at 2 months of age (data not shown).

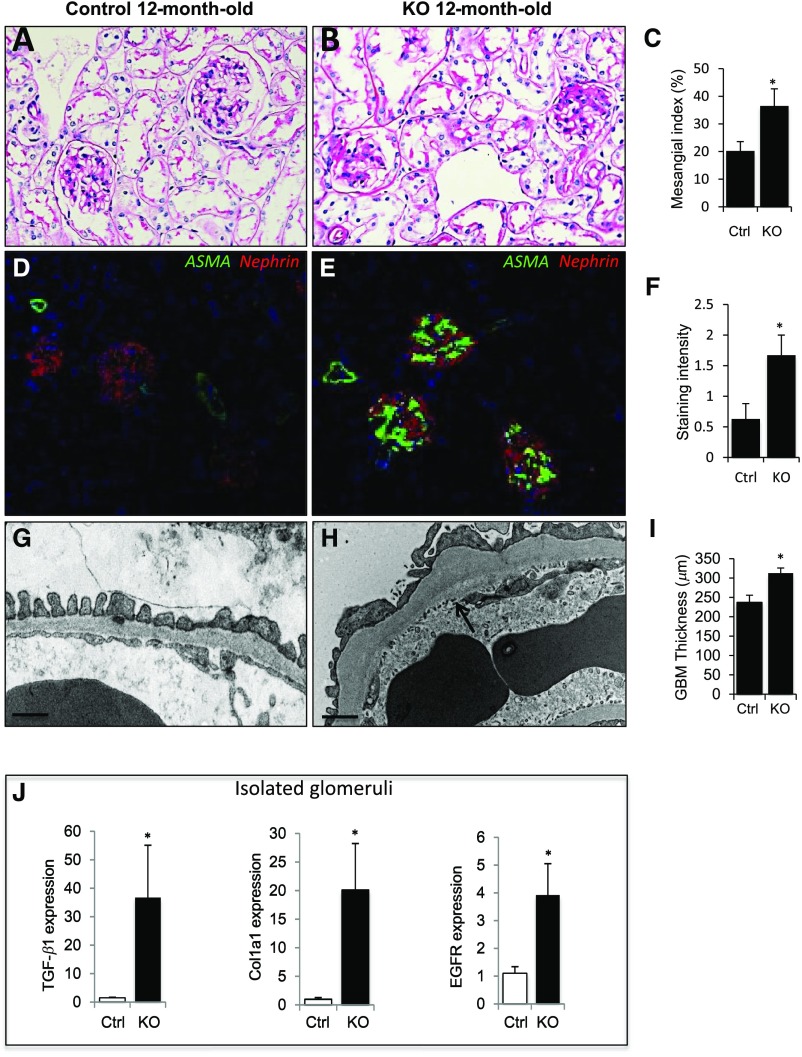

Gprc5a Deficiency Results in Thickening of the GBM and Activation of Profibrotic Signaling Pathways

To evaluate the effects of aging on Gprc5a-deficient glomeruli, we analyzed albuminuria, blood chemistry, and kidney histology in mice at 12 months of age. No significant albuminuria or increase in BUN was detected in 12-month-old −/− mice (Supplemental Table 4). In histologic examination, PAS staining revealed a significant expansion of mesangial matrix in −/− mice (Figure 4, A and B). This was validated by measuring mesangial index and by a semiquantitative scoring of mesangial expansion (Figure 4C, Supplemental Figure 4E). To analyze mesangial cell phenotype in more detail, we performed immunostaining for α–smooth muscle actin (αSMA), a marker for the activation of mesangial cells.13 The expression of αSMA was clearly upregulated in knockout glomeruli (Figure 4, D and E). The increased αSMA expression was validated by semiquantitative scoring of immunofluorescence staining (Figure 4F). No tubulointerstitial changes were detected in 12-month-old −/− kidneys (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Aging Gprc5a mice develop DN-like changes in the glomerulus. (A and B) Significant mesangial expansion was detected in Gprc5a knockout animals at 12 months of age as detected by PAS staining. (C) Mesangial index shows significant expansion in −/− animals in comparison to littermate controls. (D and E) Staining for αSMA (green) is increased in −/− glomeruli as shown by immunofluorescence staining. Double labeling was performed with anti-nephrin antibody (red). (F) Semiquantitative scoring of glomerular staining validates the induction of αSMA expression in −/− mice in comparison to controls. (G and H) In electron microscopy, the thickening of the GBM (arrow) is observed and podocytes show focal foot process effacement. (I) The quantification validates the significant thickening of the GBM. (J) Expression of TGF-β, Col1a1, and EGFR genes in isolated glomeruli is upregulated in 12-month-old −/− mice as shown by qPCR. Original magnifications, ×200 (A and B); ×100 (D and E). (G and H) Scale bars=250 nm. (C, F, I, and J) Data shown as the mean±SEM; *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. CTRL, control; KO, knockout; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff staining; qPCR, quantitative-PCR.

In electron microscopic examination, we detected a striking thickening of the GBM in 12-month-old −/− mice (Figure 4, G–I). Slit diaphragms appeared intact and endothelial morphology was unaffected (Supplemental Figure 4, C and D). Moreover, podocytes showed occasional foot process effacement but this did not reach statistical significance when slits/GBM length were analyzed (Supplemental Figure 3F).

Because the GBM and mesangial matrix were expanded in 12-month-old −/− kidneys, we analyzed profibrotic signaling pathways in isolated glomeruli. Using qPCR, we detected a 35-fold upregulation of TGF-β, a cardinal driver of fibrosis, in −/− glomeruli when compared with age-matched littermates (Figure 4J). In line with this, Col1a1, a downstream effector of TGF-β, was significantly upregulated (20-fold). Because EGFR has been shown to modulate TGF-β signaling in podocytes in DN,14 we analyzed EGFR expression in −/− glomeruli. The expression of EGFR was five-fold upregulated as detected by qPCR (Figure 4J). Taken together, lack of Gprc5a in podocytes results in the activation of profibrotic signaling in glomeruli and glomerular phenotype that closely phenocopies histopathology of human DN.

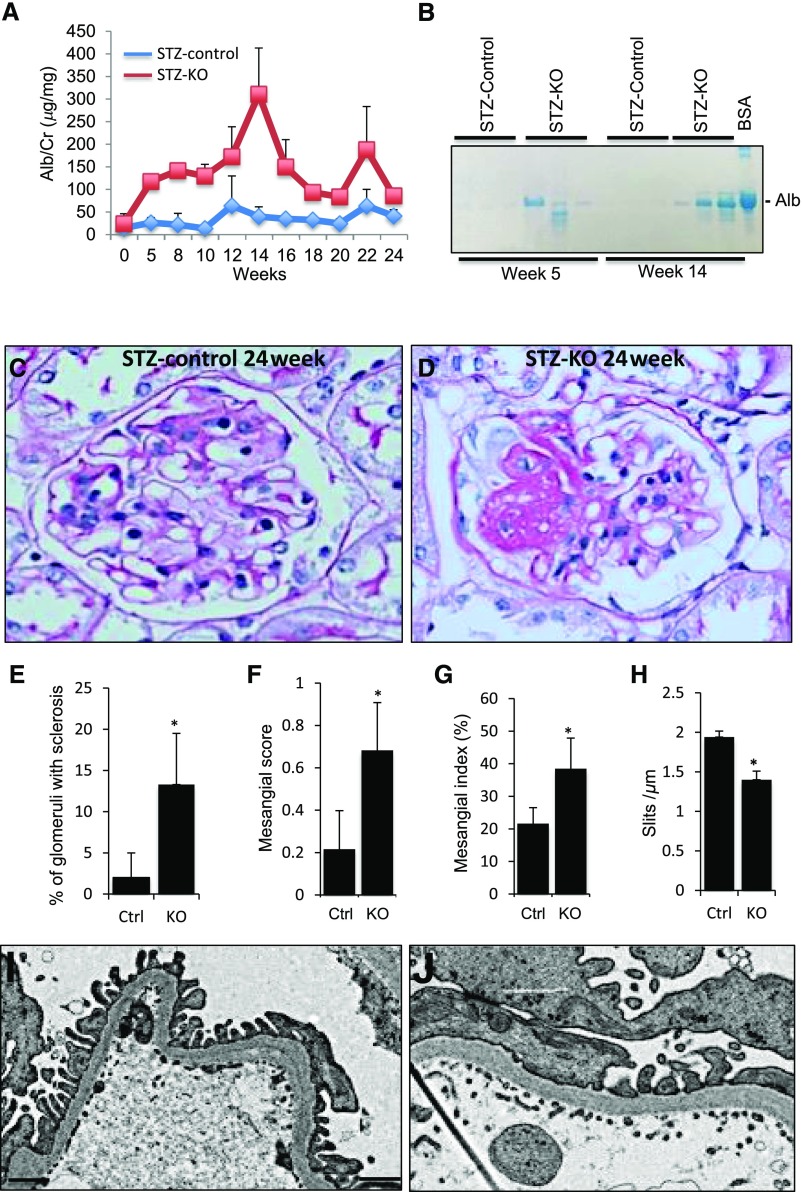

Gprc5a Deficiency Promotes Glomerular Injury in Diabetes

Because Gprc5a expression was downregulated in human DN, we wanted to analyze its pathogenic role in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetes was induced in −/− and littermate control mice at the age of 8 weeks with intraperitoneal streptozotocin injections and the mice were followed for 24 weeks. All mice developed diabetes as indicated by blood glucose values of >200 mg/dl measured 2 weeks after the induction (Supplemental Table 5 with other key parameters). Gprc5a-deficient mice were significantly more albuminuric than control STZ-treated mice as indicated by Alb/Crea ratio measurements and by analyzing urine samples on SDS-PAGE gel (Figure 5, A and B). Albuminuria was higher in −/− mice already 5 weeks after the induction of diabetes and remained elevated until the end of the experiment.

Figure 5.

Gprc5a deficiency promotes diabetic damage in the glomerulus. (A and B) After induction of diabetes with streptozotocin (STZ) (week 0), −/− mice develop higher albuminuria than STZ-treated littermate controls as shown by albumin-to-creatinine ratios and analysis of urine samples on SDS-PAGE gel. BSA was used as a positive control. (C–E) Kidney histology at 24 weeks after the induction of diabetes shows more sclerotic changes in −/− glomeruli in comparison to controls. (F and G) Mesangial index and semiquantification of mesangial changes shows significant expansion of mesangial matrix in −/− animals. (H–J) Electron microscopic examination exhibits segmental podocyte foot process effacement in −/− glomeruli, whereas foot process structure is intact in control animals. (C and D) Original magnifications, ×400. (F and G) Scale bars=250 nm. (E–H) Data shown as the mean±SEM; *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Alb, albumin; Cre, creatinine; Ctrl, control; KO, knockout.

Mice were euthanized 24 weeks after the injection and kidneys were analyzed. Macroscopically, −/− kidneys were indistinguishable from littermate controls (data not shown). Histologic examination revealed, however, more significant changes in Gprc5a-deficient glomeruli. FSGS as well as few totally sclerotic glomeruli were observed in −/− kidneys of STZ-treated mice, whereas control STZ-treated mice exhibited only discrete mesangial expansion (Figure 5, C and D). The semiquantification of sclerotic changes in glomeruli validated the significant difference between −/− and control kidneys (Figure 5E). Moreover, mesangial index and semiquantification of mesangial changes revealed significantly more prominent expansion of mesangial matrix in KO animals (Figure 5, F–H). Electron microscopic examination showed segmental foot process effacement in −/− kidneys, whereas control STZ-treated animals exhibited intact foot process architecture (Figure 5, I–J).

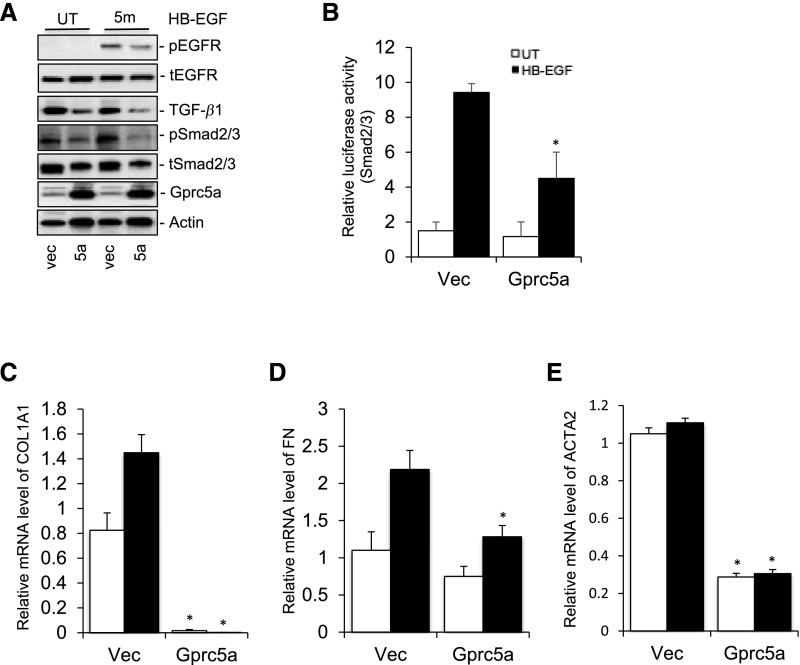

Overexpression of Gprc5a Inhibits EGFR and TGF-β Signaling in Cultured Podocytes

Next, we analyzed Gprc5a in a well established podocyte cell culture line.8 Because endogenous expression of Gprc5a was rather low in cultured cells, we started by generating a stable overexpressing cell line. The overexpression was validated by western blotting (Figure 6A) and localization of Gprc5a to the plasma membrane was shown by immunofluorescence staining (Supplemental Figure 4A). We analyzed signaling mediated by EGFR because Gprc5a has been linked to EGFR in the lung.11 The stable overexpression of Gprc5a in podocytes inhibited EGFR activation after EGF stimulation as detected by decreased receptor phosphorylation (Figure 6A). Overexpression also blunted downstream signaling to TGF-β pathway as detected by decreased TGF-β levels and Smad2/3 phosphorylation (Figure 6A). Expressional changes were validated by calculating normalized densities in the blot (Supplemental Figure 4B). Inhibition of TGF-β signaling was further confirmed in a luciferase assay using Smad2/3 responsive element because podocytes overexpressing Gprc5a showed decreased luciferase activity after EGF stimulation (Figure 6B). To validate that Gprc5a modulated also downstream targets of TGF-β signaling, we performed qPCR experiments for collagen 1 α 1 (COL1A), fibronectin, and αSMA. As expected, overexpression of Gprc5a blunted the activation of COL1A1, fibronectin, and αSMA expression after EGF exposure (Figure 6, C–E).

Figure 6.

Overexpression of Gprc5a inhibits EGFR activation and TGF-β signaling. (A) Western blotting shows blunted activation of EGFR and Smad2/3, as well as decreased expression of TGF-β1 after exposure to HB-EGF in Gprc5a-overexpressing cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) In the luciferase assay, the activation of Smad2/3 is diminished after exposure to HB-EGF in cells overexpressing Gprc5a. (C–E) Overexpression of Gprc5a suppresses expression of Col1A1, fibronectin, and αSMA genes after exposure to HB-EGF as detected by qPCR. (B–E) Data shown as the mean±SEM; *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. 5a, Gprc5a; FN, fibronectin; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; UT, untreated cells; Vec, empty vector.

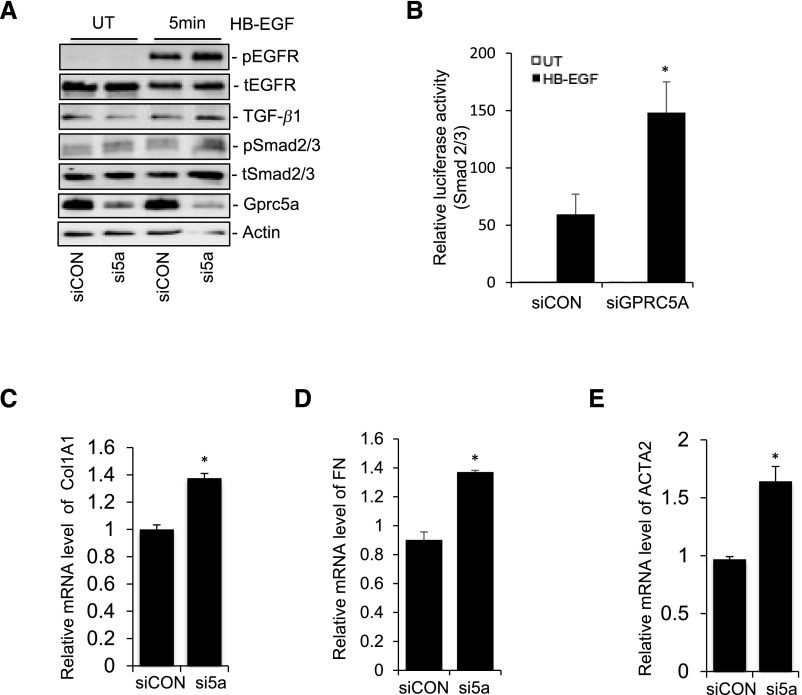

Silencing Gprc5a Expression Promotes EGFR and TGF-β Signaling in Cultured Podocytes

Although endogenous expression of Gprc5a in cultured podocytes was clearly weaker than in vivo (data not shown), we silenced the gene using siRNA to see whether this expression had remaining effects on cellular signaling. The silencing of Gprc5a in podocytes promoted EGFR activation after EGF stimulation as detected by increased receptor phosphorylation (Figure 7A). Silencing promoted also downstream signaling to TGF-β pathway as detected by increased TGF-β levels and Smad2/3 phosphorylation (Figure 7A). Expressional changes were validated by calculating normalized densities in the blot (Supplemental Figure 5C). Activation of TGF-β signaling was further confirmed in a luciferase assay using Smad2/3 responsive element because podocytes overexpressing Gprc5a showed increased luciferase activity after EGF stimulation (Figure 7B). To analyze whether the silencing of Gprc5a also had effects on downstream targets of TGF-β, we analyzed the expression of COL1A1, fibronectin, and αSMA using qPCR. In line with our results in overexpression experiments, silencing of Gprc5a with siRNA promoted the expression of COL1A1, fibronectin, and αSMA in comparison to control cells (Figures 7, C–E, and 8).

Figure 7.

Silencing of Gprc5a expression promotes EGFR activation and TGF-β signaling. (A) Western blotting shows increased activation of EGFR and Smad2/3, as well as increased expression of TGF-β1 after exposure to HB-EGF in Gprc5a silenced cells. Actin was used as a loading control. (B) In the luciferase assay, the activation of Smad2/3 is promoted after exposure to HB-EGF in cells with silenced Gprc5a expression. (C–E) Silencing of Gprc5a expression promotes the expression of Col1A1, fibronectin, and αSMA genes after exposure to HB-EGF as detected by qPCR. (B–E) Data shown as the mean±SEM; *P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. FN, fibronectin; HB-EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor; UT, untreated cells.

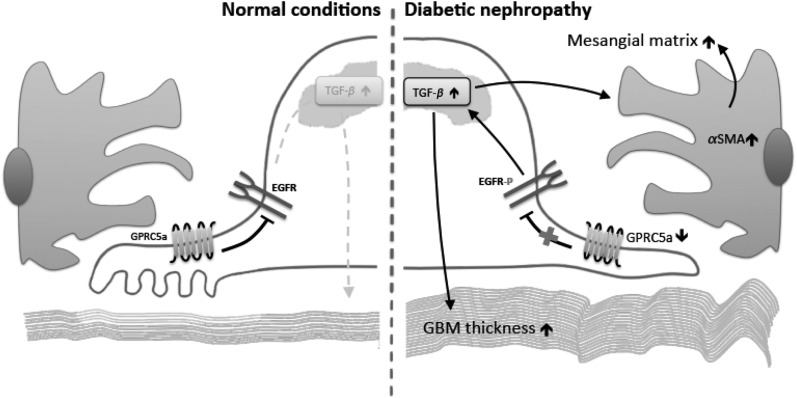

Figure 8.

Hypothetical model showing how Gprc5a-depletion activates EGFR-mediated matrix production in DN. In normal conditions (left), Gprc5a inhibits the activation of EGFR. In DN (right), the expression of Gprc5a is downregulated leading to loss of inhibitory signals that results in phosphorylation of EGFR. EGFR activates TGF-β signaling that causes the activation of mesangial cells and increased matrix deposition in both the GBM and the mesangium.

Discussion

Podocyte damage, mediated for instance by TGF-β and EGF signaling, is a central event in the pathogenesis of DN.15 In this study, we have identified a novel highly podocyte-specific GPCR, Gprc5a, which can allow us to manipulate these pathogenic signaling pathways in a cell-specific fashion. We show that: (1) Gprc5a is expressed highly by podocytes and not by other cells in the kidney, (2) Gprc5a expression is significantly downregulated in patients with DN, (3) inactivation of Gprc5a in mice results in DN-like phenotype and promotes glomerular injury in diabetes, and (4) Gprc5a modulates EGFR and TGF-β signaling pathways. Thus, Gprc5a plays a pathogenic role in the nephropathy and we propose that Gprc5a can be an interesting novel molecular target providing the possibility to develop a cell-specific therapy option for DN.

Renal fibrosis is a hallmark of CKD and predicts poor prognosis for renal insufficiency.16 TGF-β plays a critical role in the progression of renal fibrosis.1 Therefore, the pharmaceutic industry has tried to develop molecular compounds that would inhibit the signaling pathway.17 However, targeting TGF-β in a systemic fashion may induce unexpected effects because TGF-β can have both profibrotic and anti-inflammatory roles.18 This dual role can be one of the reasons for a recently failed clinical trial with anti–TGF-β therapy in DN.17 Similarly, EGFR has gained a lot of attention in kidney diseases because its activation is involved in the pathogenesis of acute and chronic renal injuries.19,20 Activation of EGFR can result in beneficial or detrimental consequences in the kidney, depending on the particular setting.20 In AKI, EGFR activation promotes recovery of renal function and structure. In chronic disease models, however, EGFR activation contributes to development and progression of renal diseases.19,20 Opposing effects of EGFR in kidney diseases have compromised possibilities to use it as a target of pharmaceutic intervention.

In this study, we show that a highly podocyte-specific GPCR, Gprc5a, regulates both EGFR and TGF-β signaling pathways in podocytes. Thus, Gprc5a offers us an opportunity to modulate these two critical signaling pathways in a cell-specific fashion and in that way escape potential effects resulting from systemic modulation of cellular signaling. Previous studies have shown that inactivation of EGFR exclusively in podocytes protects kidneys from DN,13 which underlines the key role of this pathway in podocytes. The activation of EGFR plays a critical role also in the development of rapidly progressive GN.21 It will be interesting to evaluate how Gprc5a is modulated in other glomerular disease processes.

On the basis of our findings in human DN and in Gprc5a-deficient mice, we believe that chronic reduction in Gprc5a expression plays a pathogenic role in the progression of DN. One possibility is that the reduced Gprc5a expression drives the dedifferentation of podocytes and in that way promotes disease progression. Our cell culture studies have, on the other hand, only limited value in this respect because the short-term nature of these experiments cannot copy the chronic nature of DN. However, the results in cell culture support our other findings in mice showing that Gprc5a modulates EGFR and TGF-β signaling in podocytes.

Gprc5a is a novel molecular player restricted to the glomerular podocyte that plays an important role under normal physiologic conditions and that additionally possesses disease-modifying properties. Although these observations highlight the involvement of Gprc5a in determining podocyte and renal health, a druggability assessment of this receptor reveals a number of challenges. Although classified as a GPCR of receptor class C (metabotropic glutamate receptor–like), Gprc5a does not possess the long amino-terminal domain that characterizes the metabotropic glutamate receptors of this family and that is requisite for ligand binding, receptor activation, and G-protein coupling.22 Gprc5a is an orphan receptor and there is currently no evidence indicating that this GPCR couples to G-proteins.23 Needless to say, it is challenging to develop a screening cascade without identification of ligands and substantial pathway investigation. Whether Gprc5a can be ligand activated or whether alternative strategies to manipulate its signaling function are feasible will require dedicated investigation.

Disclosures

M.L. is employed by AstraZeneca. J.P.’s research is supported by AstraZeneca.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by KI/AZ Integrated Cardio Metabolic Center, Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, Swedish Diabetes Foundation, Westmans Foundation, Karolinska Institute Foundation and through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between the Stockholm County Council and the Karolinska Institute.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017101135/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Chang AS, Hathaway CK, Smithies O, Kakoki M: Transforming growth factor-β1 and diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F689–F696, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reidy K, Kang HM, Hostetter T, Susztak K: Molecular mechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. J Clin Invest 124: 2333–2340, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wacker D, Stevens RC, Roth BL: How ligands illuminate GPCR molecular pharmacology. Cell 170: 414–427, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrakka J, Xiao Z, Nukui M, Takemoto M, He L, Oddsson A, et al.: Expression and subcellular distribution of novel glomerulus-associated proteins dendrin, ehd3, sh2d4a, plekhh2, and 2310066E14Rik. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 689–697, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patrakka J, Ruotsalainen V, Ketola I, Holmberg C, Heikinheimo M, Tryggvason K, Jalanko H. Expression of nephrin in pediatric kidney diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol 12(2): 289–296, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sistani L, Dunér F, Udumala S, Hultenby K, Uhlen M, Betsholtz C, et al.: Pdlim2 is a novel actin-regulating protein of podocyte foot processes. Kidney Int 80: 1045–1054, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sistani L, Rodriguez PQ, Hultenby K, Uhlen M, Betsholtz C, Jalanko H, et al.: Neuronal proteins are novel components of podocyte major processes and their expression in glomerular crescents supports their role in crescent formation. Kidney Int 83: 63–71, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saleem MA, O’Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, et al.: A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 630–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stitt-Cavanagh EM, Faour WH, Takami K, Carter A, Vanderhyden B, Guan Y, et al.: A maladaptive role for EP4 receptors in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1678–1690, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenoir O, Milon M, Virsolvy A, Hénique C, Schmitt A, Massé JM, et al.: Direct action of endothelin-1 on podocytes promotes diabetic glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1050–1062, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong S, Yin H, Liao Y, Yao F, Li Q, Zhang J, et al.: Lung tumor suppressor GPRC5A binds EGFR and restrains its effector signaling. Cancer Res 75: 1801–1814, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woroniecka KI, Park AS, Mohtat D, Thomas DB, Pullman JM, Susztak K: Transcriptome analysis of human diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes 60: 2354–2369, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagai K, Tominaga T, Ueda S, Shibata E, Tamaki M, Matsuura M, et al.: Mesangial cell mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 activation results in mesangial expansion. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 2879–2885, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Chen JK, Harris RC: EGF receptor deletion in podocytes attenuates diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 1115–1125, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herman-Edelstein M, Weinstein T, Gafter U: TGFβ1-dependent podocyte dysfunction. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 22: 93–99, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffield JS: Cellular and molecular mechanisms in kidney fibrosis. J Clin Invest 124: 2299–2306, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voelker J, Berg PH, Sheetz M, Duffin K, Shen T, Moser B, et al.: Anti-TGF-β1 antibody therapy in patients with diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 953–962, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sureshbabu A, Muhsin SA, Choi ME: TGF-β signaling in the kidney: Profibrotic and protective effects. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 310: F596–F606, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harskamp LR, Gansevoort RT, van Goor H, Meijer E: The epidermal growth factor receptor pathway in chronic kidney diseases. Nat Rev Nephrol 12: 496–506, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J, Liu N, Zhuang S: Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in acute and chronic kidney injury. Kidney Int 83: 804–810, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bollée G, Flamant M, Schordan S, Fligny C, Rumpel E, Milon M, et al.: Epidermal growth factor receptor promotes glomerular injury and renal failure in rapidly progressive crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nat Med 17: 1242–1250, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bräuner-Osborne H, Krogsgaard-Larsen P: Sequence and expression pattern of a novel human orphan G-protein-coupled receptor, GPRC5B, a family C receptor with a short amino-terminal domain. Genomics 65: 121–128, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou H, Rigoutsos I: The emerging roles of GPRC5A in diseases. Oncoscience 1: 765–776, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.