Abstract

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for ESRD but is complicated by the response of the recipient’s immune system to nonself histocompatibility antigens on the graft, resulting in rejection. Multiphoton intravital microscopy, referred to as four-dimensional imaging because it records dynamic events in three-dimensional tissue volumes, has emerged as a powerful tool to study immunologic processes in living animals. Here, we will review advances in understanding the complex mechanisms of T cell–mediated rejection made possible by four-dimensional imaging of mouse renal allografts. We will summarize recent data showing that activated (effector) T cell migration to the graft is driven by cognate antigen presented by dendritic cells that surround and penetrate peritubular capillaries, and that T cell–dendritic cell interactions persist in the graft over time, maintaining the immune response in the tissue.

Keywords: transplantation, rejection, lymphocytes, intravital multiphoton microscopy, effector CD8 T cells, dendritic cells

Kidney transplantation is the treatment of choice for ESRD.1 With the exception of organ transplantation between monozygotic twins, grafts are identified as foreign by the recipient’s immune system, triggering the alloimmune response that causes rejection. Continuous immunosuppression is therefore required to sustain graft function, and the complex immunosuppression regimens used today are fraught with side effects that render the patient susceptible to infection and malignancy. As such, chronic immunosuppression is a balancing act between maximizing graft protection from rejection and minimizing morbidities caused by immunosuppression. The net outcome is suboptimal long-term renal allograft survival that ranges between 50% and 60% at 10 years.2

It has long been established that the essential player in rejection is the T lymphocyte.3–5 Rejection of a transplanted organ is mediated by both naïve and memory T cells that recognize antigens expressed by donor but not host cells.6,7 Naïve T cells bearing T cell receptors (TCRs) specific to donor antigens, termed alloantigens, are first primed in secondary lymphoid tissues by antigen-presenting cells,8,9 particularly dendritic cells (DCs).10 These activated T cells differentiate into effector T cells that migrate to and reject the allograft directly via cytotoxic effects on graft cells and indirectly by attracting and activating macrophages and granulocytes. They also provide help to B cells to produce alloantibodies.11 Memory T cells, in a more direct manner, are able to migrate to the graft and generate effectors in situ without the need for secondary lymphoid organs.12–14 Alloreactive memory T cells are surprisingly prevalent in humans and experimental animals, who have never received a graft, due to TCR crossreactivity.6 Moreover, memory cells are less susceptible to most immunosuppressants.11 Therefore, how effector and memory T cells migrate to the transplanted kidney and sustain immunity locally is central to understanding the rejection process and devising strategies to combat it.

Four-Dimensional Multiphoton Intravital Microscopy

Four-dimensional multiphoton intravital microscopy, or 4-D imaging in short, is a powerful tool to visualize the cellular dynamics of the immune response by imaging fluorescent immune cells in a defined tissue volume in their native environment over time.15 Briefly, the organ of interest is exposed and immobilized without severing its blood supply from the living animal. Genetically or chemically labeled fluorescent immune cells passing or residing in that organ are then excited by the simultaneous absorption of energy from two photons (each contributing half of the energy required to induce fluorescence) emitted by special lasers. Excitation occurs only at the focal point of the objective where the two photons are absorbed, minimizing photo-toxicity and enabling photo-sectioning of the tissue. In addition, multiphoton microscopy allows deep tissue penetration (up to a few hundred micrometers) and fast image acquisition (up to 30 fps). Computer software then reconstructs high-resolution three-dimensional volumes of the fluorescent signal over time to create 4-D images (Supplemental Movies). These movies capture the dynamic behavior of individual immune cells as well as interactions between immune cells labeled with different fluorophores. Image analysis software allows investigators to quantify key dynamic elements such as cell speed, displacement, contact time with other cells, and changes in cell size, shape, or activation status.

4-D Insights into T Cell Migration to Mouse Kidney Allografts

Inhibition of T cell migration by integrin blockade is known to inhibit rejection16,17 but is accompanied by unacceptable risks including progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.18 To find alternate means of blocking T cell migration, investigators have instead focused on interrupting chemokine action. It was initially assumed that T cells migrating to an allograft utilize the classic inflammatory adhesion cascade in which fast-acting selectin binding induces slow rolling of T cells followed by sensing of chemokines present on the inflamed endothelium. Binding of chemokines to chemokine receptors on T cells causes G-protein–dependent, inside-out signaling that results in integrin activation, firm adhesion, and transmigration into the tissue.19,20 Several studies, however, showed that blocking chemokine receptors highly expressed on activated T cells, namely CXCR3 and CCR5, has little or no effect on the migration of donor-specific (allospecific) effector or memory T cells to transplanted organs.21 Even more surprising, wholesale blockade of chemokine receptor signaling using pertussis toxin (PTx), which irreversibly inhibits Gαi function,22 failed to block the migration of these cells or to significantly delay rejection of heart or kidney allografts in the mouse.23 Therefore, signaling through Gαi-coupled chemokine receptors turned out to be not essential for the migration of effector or memory T cells to transplanted organs.

Our group resorted to 4-D imaging to re-explore how activated T cells migrate to kidney allografts.23 Using donor kidneys that ubiquitously express ovalbumin (OVA), a protein not normally expressed in mice, and OT-I CD8+ T cells that carry a transgenic TCR specific to OVA-derived peptide (SIINFEKL) presented in the context of the MHC-I molecule H2-Kb, we directly visualized the dynamic behavior of antigen-specific T cells in the allograft. We studied effector and memory OT-I cell arrest, defined as cell velocity <2 µm/min, and transendothelial migration, defined as change in location from the fluorescently labeled intracapillary space into the nonfluorescent extravascular space. Both arrest and transmigration were found to occur readily, with and without PTx treatment. However, this behavior disappeared in the absence of the cognate antigen (OVA). P14 cells, CD8+ T cells that express an irrelevant transgenic TCR specific to a viral antigen absent from the graft, were found to only arrest and transmigrate if OT-I cells were present. PTx treatment of P14 cells abolished their arrest and migration. Therefore, alloantigen-specific T cells (OT-I) responding to donor antigen firmly arrest in blood vessels (capillaries) and subsequently transmigrate in a manner that is independent of chemokine signaling. In contrast, nonspecific or bystander T cells (P14) are “dragged along” by alloantigen-specific T cells via chemokines.

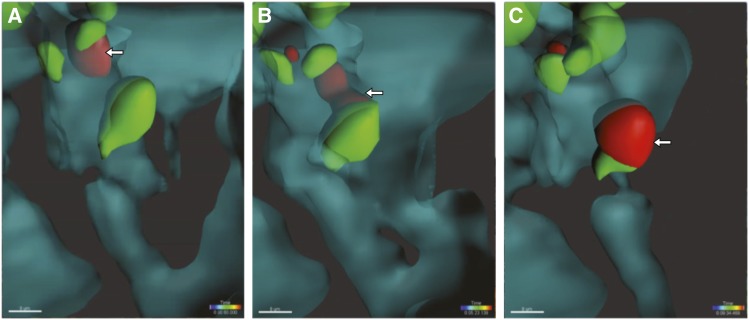

The presentation of alloantigen by allograft cells is therefore crucial to T cell infiltration into the graft, but is this function carried out by endothelial cells that line the renal vasculature or is it perhaps mediated by professional antigen-presenting cells (specifically, DC) that surround the vessels? To answer this question, we devised an experimental model in which antigen presentation was restricted to either endothelial cells or to bone marrow–derived cells.23 Using intravital imaging, we found that either the endothelium or CD11c+ DCs in the kidney are sufficient for antigen-specific T cell transmigration. These contributions were not equal, however, with DCs being more potent at arresting T cells. Careful analysis of 4-D images showed that renal DCs in both native and transplanted kidneys extend cellular processes into capillary lumina and contact blood-borne T cells.23,24 T cells subsequently arrest firmly and transmigrate, and remarkably stay in contact with the DC throughout this entire process (Figure 1).23 DC-driven arrest and transmigration of circulating effector T cells into the kidney had not been previously appreciated, illustrating the power of 4-D imaging in elucidating fundamental, in vivo biologic processes.

Figure 1.

Pericapillary DCs assist in the transmigration of effector T cells into the transplanted kidney. Two-photon intravital imaging of mouse renal allograft demonstrating effector T cell (red) interaction with peritubular capillary DCs (green) throughout the transendothelial migration process. Shown are iso-surfaces, intravascular space in cyan with 50% opacity, extravascular space in black. Arrows point to effector T cell (A) inside the capillary lumen, (B) in the process of transmigrating while maintaining contact with a DC, and (C) after it has transmigrated to the extravascular space.

DC–T Cell Interaction Continues within the Graft Parenchyma

It is established that donor-derived DCs that are transplanted with the graft (so-called passenger leukocytes) migrate rapidly out of the graft, are eliminated by recipient NK cells quickly, and are replaced by host DCs.25,26 Host DCs that infiltrate the graft after transplantation derive primarily from host monocytes, which migrate into the allograft, acquire DC morphology, produce IL-12, and induce type 1 polarization.27,28 Type 1 is the T cell phenotype characterized by IFNγ production and most closely associated with graft rejection. Host-derived DCs are present in allograft tissue in much greater numbers than their donor-derived brethren, composing >90% of kidney and heart graft-resident DCs by day 7 after transplantation.28 Indeed, monocyte precursors of DCs sense allogeneic nonself intrinsically, independent of the adaptive immune system, through mechanisms that predate the adaptive immune system.27,29 It is believed that this sensing is responsible for perpetual infiltration of allografts with host-derived DCs.30

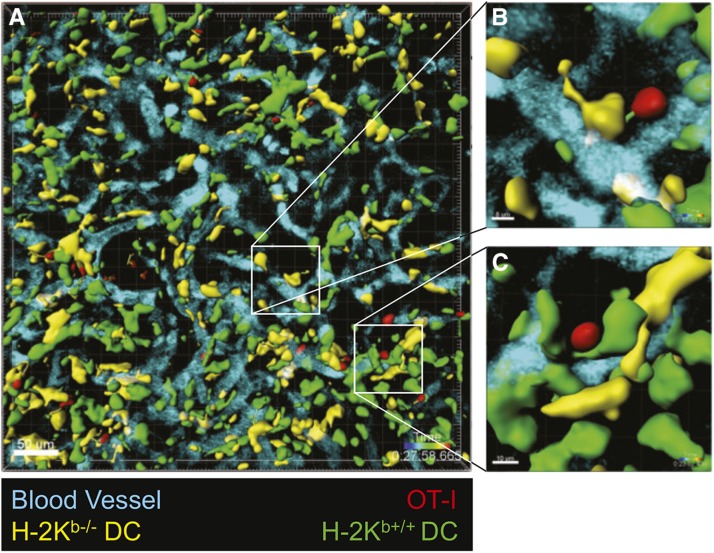

As stated in the previous section, 4-D imaging was instrumental in demonstrating that renal DCs project processes into the capillaries of native and transplanted mouse kidneys. In both cases, they “fish” for activated, circulating T cells using antigenic lures.24,28 However, what role do renal DCs have after they capture effector and memory T cells and assist in their extravasation? 4-D imaging once again provided an answer that could not be reached through other techniques. Stable contacts, defined as contacts<2 µm between cells with a velocity<2 µm/min, have previously been observed between DCs and T cells in skin31 and lung32 allografts. However, the nature and purpose of these interactions remained unknown. Previous work by our group showed that, within kidney allografts, overall mobility of antigen-specific T cells depended significantly on the ability of host-derived DCs to present antigen, with antigen presentation coinciding with lower T cell velocities and greater arrest coefficients.23 This suggested the presence of antigen-dependent (cognate) interactions between T cells and DCs. To determine if T cells continue to have cognate interactions with host DCs after they infiltrate the graft tissue, we generated mixed bone marrow chimeras by transplanting bone marrow in which 50% of DCs were MHC-I−/− (specifically H2-Kb−/−CD11c-YFP+), and therefore cannot present OVA antigen to OT-I cells, whereas the other 50% were H2-Kb+/+CX3CR1-GFP+ and can present OVA antigen. These mice were then used as recipients of (B6xBalb/c)F1-OVA kidney allografts followed by adoptive transfer of OT-I effector T cells 7 days later. Because the renal allografts were quickly infiltrated with both antigen-presenting (H2-Kb+/+) and non–antigen-presenting (H2-Kb−/−) DCs that can be distinguished by their fluorescent labels (GFP versus YFP, respectively), we were able to compare by 4-D imaging the dynamics of T cells interacting with either DC type (Figure 2). Twenty-four hours after OT-I transfer, we observed that >90% of OT-I effectors had transmigrated into the graft interstitium and >80% of these cells made extended contacts (>2 minutes) with recipient-derived DCs. However, OT-I cells interacted more frequently with H2-Kb+/+ than H2-Kb−/− DCs and, importantly, had significantly longer contact times with the former (18 versus 6 minutes mean contact time).28 By tracking OT-I movement within the graft interstitium, we noted that OT-I that contacted H2-Kb+/+ DCs had significantly lower mean velocity and higher mean arrest coefficient than OT-I that contacted only H2-Kb−/− DCs. Therefore, by presenting cognate antigen, DCs play an important role in arresting T cells within the allograft interstitium.

Figure 2.

Cognate DC–T cell interactions persist in the renal transplant parenchyma. Kidney allografts were transplanted to B6 mixed bone marrow chimeras that harbor equal numbers of H2-Kb−/− (YFP+) and H2-Kb+/+ (GFP+) DCs. OT-I effector T cells were transferred 6 days after transplantation and intravital two-photon microscopy was performed 1 day later. (A) Representative, volume-rendered image of kidney allograft with insets showing (B) an OT-I cell (red) in brief contact with a H2-Kb−/− DC (yellow), and (C) an OT-I cell (red) in stable contact with an H2-Kb+/+ DC (green). Note the dragon tails depicting the trajectory of the T cells (visible for T cell briefly interacting with ko-DC). Also see corresponding Supplemental Movies.

In a separate model, F1-OVA kidneys were transplanted into B6 mice expressing diphtheria toxin receptor under the control of the CD11c promoter, therefore allowing DC depletion. By depleting DC after OT-I transfer and migration into the graft’s interstitium, we determined that DC elimination resulted in significant increases in OT-I cell velocities and significant decreases in arrest coefficients. It is widely postulated that increased T cell arrest coefficient translates to increased T cell activity and ultimately rejection.33,34 Indeed, delayed administration of diphtheria toxin was found to delay graft rejection by endogenous T cells. Additionally, early administration of diphtheria toxin to mice that lacked secondary lymphoid tissue prevented rejection of cardiac allografts by donor-specific effector T cells. Investigation of infiltrating CD4 and CD8 T cells isolated from grafts after DC depletion showed an increase in apoptosis markers and decrease in proliferation markers (Ki67).28 Together with the 4-D imaging data, these findings indicate that intragraft DCs play an essential role in the rejection process. They capture donor antigen–specific effector and memory T cells in the capillary space and facilitate their transmigration. Once in the interstitium, T cell survival and proliferation is sustained by antigen-presenting DCs, ultimately leading to graft rejection.

Concluding Remarks

Multiphoton intravital microscopy, or 4-D imaging, has been a crucial tool in advancing our understanding of transplant rejection because it has allowed investigators to observe the location, interaction, and dynamic behavior of immune cells in real time in the living allograft. Investigation of rejection in these four dimensions has led to the discovery that effector and memory T cell migration is primarily antigen-driven, not chemokine-driven, and that DCs reach into the capillary lumen to capture T cells. The observation that host DCs populate the transplanted graft and persist there led to the discovery that host DCs also continuously interact with captured antigen-specific T cells and sustain their activation (survival and proliferation) in the graft. These discoveries, none of which would have been possible without 4-D imaging, pave the way for better understanding of the highly complex rejection process.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 5R01 AI49466 and 4P30 DK079307, the John Merrill Grant in Transplantation (American Society of Nephrology), and a predoctoral scholarship from the American Society of Transplantation.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2017070800/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Suthanthiran M, Strom TB: Renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 331: 365–376, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, Agodoa LY, Albertus P, Ayanian J, et al. : US renal data system 2016 annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 69[3 Suppl 1]: A4, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller JFAP: Effect of neonatal thymectomy on the immunological responsiveness of the mouse. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 156: 415–428, 1962 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall BM, Dorsch S, Roser B: The cellular basis of allograft rejection in vivo. I. The cellular requirements for first-set rejection of heart grafts. J Exp Med 148: 878–889, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall BM, Dorsch S, Roser B: The cellular basis of allograft rejection in vivo. II. The nature of memory cells mediating second set heart graft rejection. J Exp Med 148: 890–902, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lakkis FG, Lechler RI: Origin and biology of the allogeneic response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3, a014993, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macedo C, Orkis EA, Popescu I, Elinoff BD, Zeevi A, Shapiro R, et al.: Contribution of naïve and memory T-cell populations to the human alloimmune response. Am J Transplant 9: 2057–2066, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakkis FG, Arakelov A, Konieczny BT, Inoue Y: Immunologic ‘ignorance’ of vascularized organ transplants in the absence of secondary lymphoid tissue. Nat Med 6: 686–688, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P, Hwang KW, Palucki D, Kim O, Newell KA, Fu YX, et al.: Secondary lymphoid organs are important but not absolutely required for allograft responses. Am J Transplant 3: 259–266, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH: T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature 427: 154–159, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moreau A, Varey E, Anegon I, Cuturi MC: Effector mechanisms of rejection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 3, a015461, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chalasani G, Dai Z, Konieczny BT, Baddoura FK, Lakkis FG: Recall and propagation of allospecific memory T cells independent of secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 6175–6180, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obhrai JS, Oberbarnscheidt MH, Hand TW, Diggs L, Chalasani G, Lakkis FG: Effector T cell differentiation and memory T cell maintenance outside secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol 176: 4051–4058, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenk AD, Nozaki T, Rabant M, Valujskikh A, Fairchild RL: Donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells infiltrate cardiac allografts within 24-h posttransplant in naive recipients. Am J Transplant 8: 1652–1661, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinselmeyer BH, Dempster J, Wokosin DL, Cannon JJ, Pless R, Parker I, et al.: Chapter 16. Two-photon microscopy and multidimensional analysis of cell dynamics. Methods Enzymol 461: 349–378, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Setoguchi K, Schenk AD, Ishii D, Hattori Y, Baldwin WM 3rd, Tanabe K, et al.: LFA-1 antagonism inhibits early infiltration of endogenous memory CD8 T cells into cardiac allografts and donor-reactive T cell priming. Am J Transplant 11: 923–935, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitchens WH, Haridas D, Wagener ME, Song M, Kirk AD, Larsen CP, et al.: Integrin antagonists prevent costimulatory blockade-resistant transplant rejection by CD8(+) memory T cells. Am J Transplant 12: 69–80, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carson KR, Focosi D, Major EO, Petrini M, Richey EA, West DP, et al.: Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: A review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) project. Lancet Oncol 10: 816–824, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Springer TA: Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: The multistep paradigm. Cell 76: 301–314, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shulman Z, Shinder V, Klein E, Grabovsky V, Yeger O, Geron E, et al.: Lymphocyte crawling and transendothelial migration require chemokine triggering of high-affinity LFA-1 integrin. Immunity 30: 384–396, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberbarnscheidt MH, Walch JM, Li Q, Williams AL, Walters JT, Hoffman RA, et al.: Memory T cells migrate to and reject vascularized cardiac allografts independent of the chemokine receptor CXCR3. Transplantation 91: 827–832, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spangrude GJ, Sacchi F, Hill HR, Van Epps DE, Daynes RA: Inhibition of lymphocyte and neutrophil chemotaxis by pertussis toxin. J Immunol 135: 4135–4143, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walch JM, Zeng Q, Li Q, Oberbarnscheidt MH, Hoffman RA, Williams AL, et al.: Cognate antigen directs CD8+ T cell migration to vascularized transplants. J Clin Invest 123: 2663–2671, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yatim KM, Gosto M, Humar R, Williams AL, Oberbarnscheidt MH: Renal dendritic cells sample blood-borne antigen and guide T-cell migration to the kidney by means of intravascular processes. Kidney Int 90: 818–827, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garrod KR, Liu FC, Forrest LE, Parker I, Kang SM, Cahalan MD: NK cell patrolling and elimination of donor-derived dendritic cells favor indirect alloreactivity. J Immunol 184: 2329–2336, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garrod KR, Wei SH, Parker I, Cahalan MD: Natural killer cells actively patrol peripheral lymph nodes forming stable conjugates to eliminate MHC-mismatched targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 12081–12086, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberbarnscheidt MH, Zeng Q, Li Q, Dai H, Williams AL, Shlomchik WD, et al.: Non-self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest 124: 3579–3589, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuang Q, Liu Q, Divito SJ, Zeng Q, Yatim KM, Hughes AD, et al.: Graft-infiltrating host dendritic cells play a key role in organ transplant rejection. Nat Commun 7: 12623, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai H, Friday AJ, Abou-Daya K, Williams A, Mortin-Toth S, Nicotra M, et al. : Donor SIRPα polymorphism modulates the innate immune response to allogeneic grafts. Sci Immunol 2, eaam6202, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oberbarnscheidt MH, Lakkis FG: Innate allorecognition. Immunol Rev 258: 145–149, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celli S, Albert ML, Bousso P: Visualizing the innate and adaptive immune responses underlying allograft rejection by two-photon microscopy. Nat Med 17: 744–749, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelman AE, Li W, Richardson SB, Zinselmeyer BH, Lai J, Okazaki M, et al.: Cutting edge: Acute lung allograft rejection is independent of secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol 182: 3969–3973, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dustin ML: Stop and go traffic to tune T cell responses. Immunity 21: 305–314, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider H, Downey J, Smith A, Zinselmeyer BH, Rush C, Brewer JM, et al.: Reversal of the TCR stop signal by CTLA-4. Science 313: 1972–1975, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.