Abstract

Objective(s):

Type I IFN (IFN-I) responses confer both protective and pathogenic effects in persistent virus infections. IFN-I diversity, stage of infection and tissue compartment may account for this dichotomy. The gut is a major site of early HIV-1 replication and microbial translocation, but the nature of the IFN-I response in this compartment remains unclear.

Design:

Samples were obtained from two IRB-approved cross-sectional studies. The first study included individuals with chronic, untreated HIV-1 infection (n=24) and age/gender balanced uninfected controls (n=14). The second study included antiretroviral-treated, HIV-1-infected individuals (n=15) and uninfected controls (n=15).

Methods:

The expression of 12 IFNα subtypes, IFNβ and antiviral IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) was quantified in PBMCs and colon biopsies using real-time PCR and next-generation sequencing. In untreated HIV-1-infected individuals, associations between IFN-I responses and gut HIV-1 RNA levels as well as previously established measures of colonic and systemic immunological indices were determined.

Results:

IFNα1, IFNα2, IFNα4, IFNα5 and IFNα8 were upregulated in PBMCs during untreated chronic HIV-1 infection, but IFNβ was undetectable. By contrast, IFNβ was upregulated whereas all IFNα subtypes were downregulated in gut tissue. Gut ISG levels positively correlated with gut HIV-1 RNA and immune activation, microbial translocation and inflammation markers. Gut IFN-I responses were not significantly different between HIV-1-infected individuals on antiretroviral treatment and uninfected controls.

Conclusions:

The IFN-I response is compartmentalized during chronic untreated HIV-1 infection, with IFNβ being more predominant in the gut. Gut IFN-I responses are associated with immunopathogenesis, and viral replication is likely a major driver of this response.

Keywords: Type I Interferon, HIV-1 infection, mucosal immunology, IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), inflammation, gut

INTRODUCTION

Innate immune responses evolved to limit the initial spread of pathogens in the host, but these responses may also contribute to pathogenesis in persistent virus infections [1–4]. This dichotomy is highlighted by the role of type I interferons (IFN-I) in HIV-1 infection and in the SIV/rhesus macaque infection model. The IFN-Is are a diverse family of cytokines that include IFNα and IFNβ that signal through the type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) to induce hundreds of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) [5]. During acute HIV-1 and SIV infection, plasma levels of IFNα increased rapidly [6, 7]. Accompanying this IFN-I response, robust cellular expression of ISGs was observed in both the periphery and lymphoid tissue during acute HIV/SIV infection [6–13]. Several of these ISGs encode antiviral ‘restriction factors’. Genetic ablation of restriction factors APOBEC3 and Tetherin in murine retrovirus infection reduced the antiviral potency of administered IFNα in vivo [14, 15]. During acute SIV infection, blockade of type I IFN signaling with an IFNAR antagonist exacerbated viremia and pathogenesis [16]. Moreover, transmitted/founder HIV-1 strains that initially establish infection in vivo were relatively resistant to IFN-Is and restriction factors Mx2 and IFITMs in vitro [17–19].

The antiviral role of IFN-Is during acute HIV-1/SIV infection sharply contrasts with their emerging role during the chronic phase. Two of the most striking features of chronic untreated HIV-1 disease, inflammationand generalized immune activation, are linked to prolonged stimulation by IFN-Is [4, 20]. Indeed, a persistently elevated IFN-I response is a critical feature that distinguishes pathogenic [8, 10–12, 21–28] versus nonpathogenic SIV infections [6, 8, 29]. Of note, chronic immune activation and inflammation are associated with HIV-1 disease progression, non-AIDS comorbidities and increased mortality [30–33]. Blocking IFN-I signaling during chronic HIV-1 infection in humanized mice revived cell-mediated immune responses and reduced viremia [34, 35]. These data strengthened the case for clinically blocking IFN-I signaling to reduce inflammation and co-morbidities [36, 37]. However, IFN-Is may stillexert significant antiviral effects during chronic HIV-1 infection. Blockade of IFN-I signaling in humanized mice with antiretroviral drug-suppressed HIV-1 infection resulted in ‘blips’ of HIV-1 viremia [34].

Understanding the dichotomy of IFN-I responses would be key to harnessing the IFN-I pathway for curative and/or anti-inflammation strategies against HIV-1 infection. However, these studies may need to account for factors that drive IFN-I’s pleiotropic effects. One source of IFN-I pleiotropy is the diversity of the IFN-Is themselves. IFNα is comprised of 13 genes encoding 12 distinct subtypes that are produced primarily by plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) [38]. We previously showed that primary pDCs exposed to HIV-1 in vitro express a biased distribution of IFNα subtypes, with weakly antiviral IFNα1, IFNα2 and IFNα5 accounting for nearly half of the IFNα transcript pool [39]. Moreover, IFNβ, a single cytokine that shares only 50% homology to the IFNα subtypes, may have nonredundant functions compared to IFNα [40–43]. Interestingly, whereas IFNα levels increased in plasma from chronic HIV-1 infected individuals, IFNβ levels were mostly undetectable [23].

The IFN-I response is highly influenced by the tissue environment [44], but most data on HIV-1 infection were derived from peripheral blood. Early HIV-1 replication primarilyoccurs in the gut, suggesting that IFN-I responses may play a more important role in controlling HIV-1 replication in this compartment. The gut harbors large numbers of CCR5+ effector memory CD4+ T cells that are highly susceptible to infection by transmitted/founder HIV-1 strains. In the SIV model, pDCs are recruited early in the gut, and pDC frequency associated with increased ISG expression [45]. Importantly, increased ISG expression was associated with the accumulation of ileal pDCs in individuals with chronic HIV-1 infection [46]. Thus, a strong IFN-I signature likely occurs in the gut during chronic HIV-1 infection, similar to peripheral blood. However, the extent to which the various IFNα subtypes, IFNβ and ISGs associate with markers of gut pathogenesis remains unknown.

HIV-1 associated pathology of the gut is mediated by both virus and enteric bacteria. The loss of gut Th17 and Th22 cells likely precipitate epithelial barrier breakdown, resulting in the movement of microbes and microbial products into the lamina propria and eventually, the systemic circulation [33, 47]. This process, known as microbial translocation, is a key contributor to HIV-1-associated chronic immune activation despite effective anti-retroviral therapy (ART) [33, 47–50]. In fact, microbial exposure enhances HIV-1 replication and CD4+ T cell death in lamina propria mononuclear cells (LPMCs) ex vivo [51–53]. We profiled the transcriptome of gut CD4+ T cells exposed to Prevotella stercorea, an enteric microbe found in high relative abundance in gut mucosa of HIV-1-infected individuals [54]. The top pathway induced was the IFN-I response, involving the induction of >60 known ISGs, including several HIV-1 restriction factors [55]. This raises the possibility that microbial translocation may contribute to the elevated IFN-I response in the gut during chronic HIV-1 infection.

Given that the impact of IFN-Is may be influenced by IFN-I diversity, stage of infection and tissue environment, we investigated the nature of the gut IFN-I response during chronic HIV-1 infection. Our data revealed critical features of the chronic IFN-I response in the gut that may inform IFN-I-based strategies that target the gut to reduce chronic immune activation in HIV-1-infected individuals.

METHODS

Study participants and study design.

Colon biopsies, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plasma samples were obtained from individuals with untreated, chronic HIV-1 infection and HIV-1-seronegative (uninfected) adults enrolled in a completed IRB-approved study at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus (UC-AMC), Aurora, Colorado, USA (S1 Table). All study participants voluntarily gave written, informed consent. Inclusion and exclusion criteria and the collection, storage and processing of colon biopsies, PBMCs and plasma were extensively detailed in previous publications [56, 57].

To investigate the impact of ART on colonic type I ISG signatures, colon (sigmoid) biopsies and plasma samples were also obtained from the Rush University Medical Center (RUMC) Institutional Review Board-approvedgastrointestinal repository in Chicago, Illinois, USA. All subjects gave informed consent prior to tissue and blood collection agreeing to allow samples and their patient data to be stored for future use. Samples were shipped to UC-AMC for subsequent laboratory studies (S2 Table). All protected study participant information was de-identified to the investigators and laboratory personnel at the UC-AMC and the study approved by COMIRB. Colon biopsies were obtained from the left colon at the time of colonoscopy with a standard 2.2 mm biopsy forceps at the RUMC Endoscopy Lab. Biopsies were stored in RNAlater solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 hours at 4°C, before long term storage in −80°C freezers. Plasma was isolated from blood samples collected into a BD (Becton Dickinson) vacutainer tubes (EDTA) and stored at−80°C.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for IFNα and next-generation sequencing (NGS) for IFNα subtype determination.

Total RNA was extracted from PBMC or colon biopsies in RNAlater using Qiagen RNAeasy Micro Kit. Insufficient colonic biopsy RNA was obtained from 5 UC-AMC study participants (1 uninfected, 4 HIV-infected). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for total IFNα was performed as previously described [39], using primers in the conserved regions of the IFNα subtypes. Copy number was interpolated using a standard curve with 108-101 copies of IFNα8 plasmid and normalized against GAPDH copies. For quality control, RNA samples with GAPDH levels <200 copies/ng were excluded from the qPCR analysis (UC-AMC: 1 uninfected; 2 HIV-infected; RUMC: 4 uninfected).

IFNα subtype determination by NGS was performed on PBMC and colon biopsies from the UC-AMC cohorts only. Samples with insufficient RNA or GAPDH levels <200 copies/ng were excluded (PBMC: 6 uninfected, 11 HIV-1 infected; colon biopsies: 5 uninfected, 7 HIV-1 infected). cDNA was added to a PCR reaction containing Phusion Hi-Fidelity Taq (New England Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s instructions containing 10 pmol of Illumina primers [39]. Illumina sequences were compared to a reference database of the IFNα gene family with >90% identity threshold. IFNα gene distribution was calculated based on a percentage of the total IFNα counts. IFNα1 and IFNα13 DNA sequences were identical in the amplified region and encode an identical protein and so were referred to as IFNα1/13. Final numbers for PBMC and colon biopsy samples for IFNα and IFNα subtype measurement are detailed in S3 Table.

IFNβ and ISG transcript quantification.

Taqman primer probe combinations were used to quantify IFNβ, APOBEC3G, Tetherin and Mx2 relative to GAPDH. IFNβ primers included: IFNβ.forward TTGCTCTCCTGTTGTGCTTCTCCA, IFNβ.reverse TTCAAGCCTCCCATTCAATTGCC, IFNβ.probe ACTGAAAATTGCTGCTTCTTTGTAGGAATCCAAG.

All other primer sets and PCR conditions were reported previously [39]. Absolute quantification was conducted using 108-101 copies of plasmid standards for each of the gene tested and normalized to GAPDH copy numbers. Due to low RNA yields and/or GAPDH quantities, some samples were excluded from analyses. Final numbers for PBMC and colon biopsy samples for each measurement are detailed in S3 Table.

Accession numbers.

Next-generation sequencing data were deposited at the NCBI Sequence Archive Bioproject PRJNA422935.

Previously obtained measurements of colonic mucosal and systemic immunological and virological parameters in the UC-AMC cohort.

Indicators of systemic inflammation (IL6, high sensitivity C-reactive Protein (hsCRP), IFNγ, TNFα and IL10), microbial translocation (LPS, LTA) and epithelial barrier damage (intestinal fatty acid binding protein; iFAPB) as well as blood T cell activation (CD38+HLA-DR+), colonic CD4 and CD8 T cell frequencies and activation, colonic myeloid DC (mDC) and pDC frequencies and activation (CD40, CD83), constitutive colonic mucosal cytokine production, frequencies of IFNγ, IL17 and IL22-expressing colonic T cells and tissue HIV-1 RNA levels were previously evaluated in the untreated, HIV-1 infected study subjects and the methods detailed elsewhere [56, 57].

Measurements of plasma IFNα, IFNβ, sCD27 and sCD14.

Commercially available ELISAs were used to evaluate levels of IFNα, IFNβ (both PBL Assay Science), sCD27 (Invitrogen) and sCD14 (R&D Systems) in EDTA plasma samples. Manufacturer’s protocols were followed for all assays.

Statistical analysis.

Non-parametric statistics were performed with no adjustments for multiple comparisons due to the exploratory nature of this study. Analyses were undertaken using GraphPad Prism Version 6 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Outliers were identified using the Rout test (GraphPad).

RESULTS

Colon IFNβ gene transcripts are increased in chronic, untreated HIV-1 infection and correlate with indicators of systemic inflammation.

We quantified IFNα and IFNβ protein levels in plasma and IFN-I gene transcripts in paired PBMC and colon biopsies from untreated, HIV-1 infected (n=24) and uninfected (n=14) individuals from our previously completed clinical study [56–59] (S1 Table). Untreated HIV-1 infected persons had a median plasma viral load of 51,350 (range 2880–207,000) HIV-1 RNA copies/ml and 445 (221–1248) CD4 cells/μl. Median CD4 count for uninfected study participants (724, 468–1071 CD4 cells/μl) was significantly higher compared to untreated, HIV-1 infected study participants. In agreement with published data from other groups [23, 26, 27], plasma IFNα levels were significantly higher in untreated HIV-1 infected compared to uninfected study participants, whereas plasma IFNβ levels were undetectable in both cohorts (Figure 1A). These results were recapitulated at the transcriptional level, as we observed higher IFNα gene transcripts in PBMC from HIV-1 infected individuals relative to control study participants, but undetectable PBMC IFNβ gene transcripts for both groups (Figure 1B). We next evaluated the absolute gene expression of distinct IFNα subtypes in a subset of study participants for which good quality RNA sample remained available (S3Table). We observed that the higher total IFNα gene transcripts in PBMCs of HIV-infected individuals were reflected in higher levels of IFNα1 (P=0.0003), IFNα2 (P=0.02), IFNα4 (P=0.02), IFNα5 (P=0.04) and IFNα8 (P=0.06) (Figure 1C, D). No significant differences in the remaining IFNα subtypes were observed in PBMC samples between the two groups.

Figure 1. IFNα/β plasma levels and gene transcript levels in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in untreated, chronically infected HIV-1 and uninfected study participants.

(A) Levels of IFNα/β were measured in plasma samples from HIV-1 uninfected control (HIVneg; n=14) and untreated, chronic HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+; n=24) study participants. (B) IFNα/β gene transcript levels were measured in PBMC from HIV-1 uninfected (HIVneg; n=14) and untreated, chronic HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+; n=24) study participants. (C, D) Expression of IFNα subtypes (number of transcripts for each IFNα subtype relative to total IFNα gene transcripts) in PBMC were assessed in 13 HIV-infected and 8 uninfected study participants. Lines represent median values (A, B, D) or are shown as median (range) (D). *Bold font indicates a significant p value. Italics indicates a trend (P<0.1). Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test to determine differences between unmatched groups.

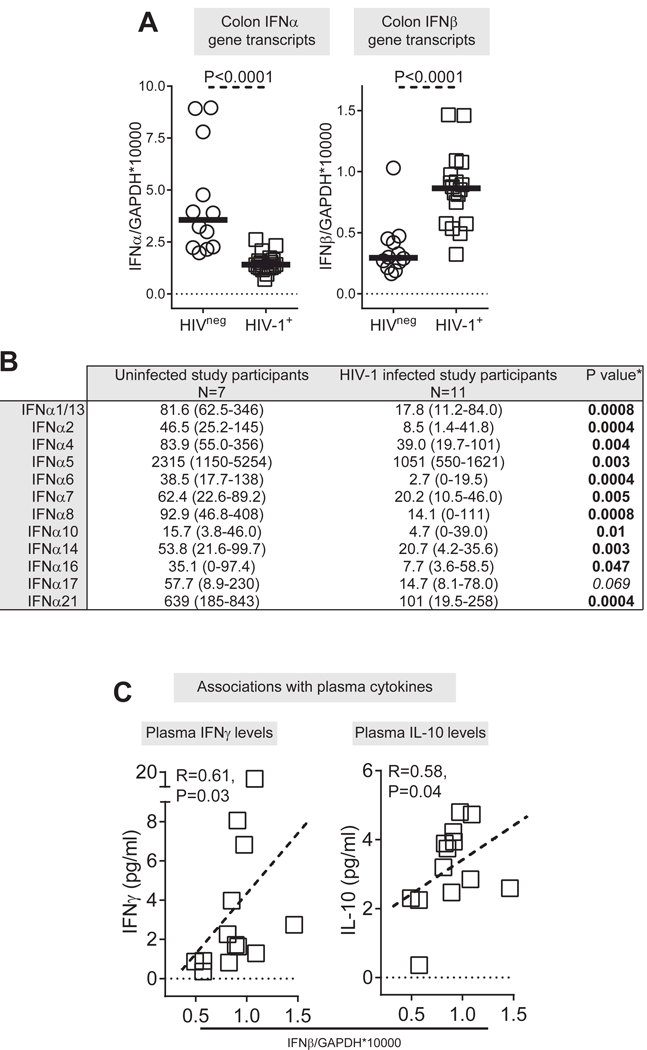

We next quantified the levels of IFNα (total and individual subtypes) and IFNβ transcripts in colonic mucosa of untreated HIV-infected and uninfected study participants (Figure 2; S3 Table). In contrast to IFNα profiles observed in PBMC, colon total IFNα gene transcripts were significantly lower in HIV-1 infected versus uninfected study participants (Figure 2A). In fact, all IFNα subtypes were expressed at lower levels in HIV-1-infected colon samples compared to uninfected study participants (Figure 2B). Surprisingly, colon IFNβ gene transcripts were significantly higher in HIV-1 infected relative to uninfected study participants (Figure 2A). We next determined whether colon IFNα and IFNβ gene expression levels in untreated, HIV-1-infected persons correlated with a battery of clinical, virological and immunological indices for pathogenesis that we measured in previous studies [56, 57] (S4 Table). IFNα/β gene transcripts did not associate with CD4 counts (Table S4). Total colon IFNα gene expression did not significantly correlate with other indices measured. By contrast, colon IFNβ gene expression significantly correlated with plasma IFNγ and IL10 levels (Figure 2C). IFNβ gene expression also associated with higher numbers of IFNγ and IL17 expressing CD4+ T cells in the tissue (S4 Table).

Figure 2. IFNα/β gene transcript levels in colonic cells in untreated, chronically infected HIV-1 and uninfected study participants.

(A) Levels of IFNα/β gene transcripts were measured in colonic samples from HIV-1 uninfected (HIVneg; n=12) and untreated, chronic HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+; n=18) study participants. Lines represent median values. (B) Expression of IFNα subtypes (number of transcripts for each IFNα subtype relative to total IFNα gene transcripts) in colonic samples were assessed in 18 HIV-infected and 8 uninfected study participants. *Bold font indicates a significant p value. Italics indicates a trend (P<0.1). (C) Correlations between IFNβ gene transcript levels and plasma levels of IFNγ and IL-10 in HIV-1 infected study participants (n=13; Plasma levels of IFNγ and IL-10 were not evaluated in 5 of the study participants with IFNβ gene expression data). Dotted line is a visual representation of the significant association. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test to determine differences between unmatched group and Spearman test to determine correlations between variables.

Colon antiretroviral gene expression in untreated HIV-1 infection positively correlates with colon HIV-1 RNA levels and immune activation.

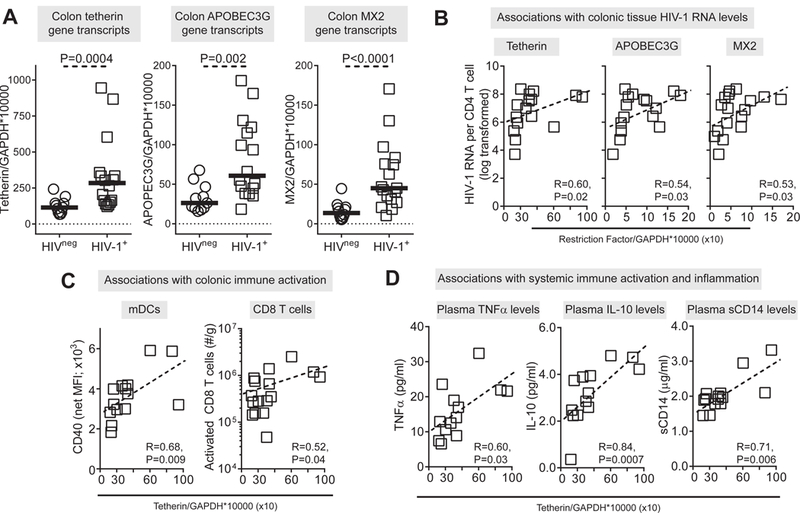

Since the IFNα subtypes and IFNβ were differentially altered in the colonic mucosa of HIV-1 infected study participants, we next evaluated if downstream ISGs were induced or inhibited. We focused on three canonical antiretroviral ISGs: Tetherin/BST-2, APOBEC3G and MX2[60]. All three ‘restriction factors’ were significantly higher in the colonic mucosa of untreated HIV-1 infected compared to uninfected study participants (Figure 3A; S3 Table), and the expression of all 3 restriction factor ISGs significantly correlated with each other (S5 Table). Interestingly, antiretroviral ISGs expression did not significantly associate with IFNα or IFNβ expression.

Figure 3. Restriction factor gene transcript levels in colonic cells in untreated, chronically infected HIV-1 and uninfected study participants.

(A) Levels of tetherin (BST2), APOBEC3G and MX2 gene transcripts were measured in colonic samples from HIV-1 uninfected (HIVneg; n=11–12) and untreated, chronic HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+; n=16–18) study participants. Lines represent median values. (B) Correlations between gene transcript levels and colonic tissue HIV-1 RNA levels in HIV-1 infected study participants (N=16 tetherin, APOBEC3G; N=17 MX2 Outlier identified using Rout test was not included in analyses). Correlations between tetherin gene transcript levels and (C) colonic mDC activation (CD40 expression levels; N=14; mDC activation levels were not measured in 2 of the study participants with tetherin gene expression data) and frequency of activated CD8+ T cells (N=16) and (D) plasma levels of TNFα (N=13), IL-10 (N=13) and sCD14 (N=14) in HIV-1 infected study participants (TNFα, IL-10 levels were not measured in 3 of the study participants and sCD14 level measured in 2 of the study participants with tetherin gene expression data). Dotted line is a visual representation of the significant association. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test to determine differences between unmatched group and Spearman test to determine correlations between variables.

We next evaluated if antiviral ISG expression correlated with colon HIV-1 RNA levels and immune parameters. Notably, these 3 ISGs positively correlated with colon HIV-1 RNA levels (Figure 3B, Table 1). Tetherin and APOBEC3G transcript levels positively correlated with the activation marker CD40 expressed on colonic mDC; and a similar trend was observed for MX2 and activated mDCs (P=0.07) (Figure 3C, Table 1). Higher tetherin and APOBEC3G gene transcripts positively associated with the constitutive production of IL12p70 by total colonic cells (Table 1). Tetherin levels correlated further with several virological and immunological parameters. Colon Tetherin levels positively correlated with plasma HIV-1 viral load, the number of activated colonic CD8+ T cells, systemic indicators of inflammation (TNFα, IL10), sCD14, an indicator of monocyte activation and indirect measure of microbial translocation, and inversely associated with epithelial barrier damage (iFABP) (Figure 3C-D, Table 1). Associations between APOBEC3G and MX2 and these clinical and systemic markers were more variable and did not consistently reach statistical significance (Table 1). No ISG gene transcripts associated with CD4 counts (Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlations between colonic restriction factor gene transcripts and clinical, virological and immunological parameters.a

| Tetherin (N=16) |

APOBEC3G (N=16) |

MX2 (N=17)b |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Parameters | |||

| Blood CD4 T cell count | R=−0.31, P=0.24 | R=−0.19, P=0.47 | R=−0.14, P=0.58 |

| Plasma HIV-1 viral load | R=0.51, P<0.05 | R=0.36, P=0.18 | R=0.46, P=0.07 |

| Systemic inflammation, immune activation, microbial translocation and epithelial barrier disruption parameters | |||

| Plasma IL-6 | R=0.33, P=0.22 | R=0.32, P=0.22 | R=0.00, P=0.98 |

| Plasma CRP | R=0.00, P=1.0 | R=0.23, P=0.39 | R=−0.12, P=0.66 |

| Plasma TNFα (N=13c, 14d ) | R=0.60, P=0.03 | R=0.51, P=0.08 | R=0.33, P=0.30 |

| Plasma IFNγ (N=13, 12) | R=0.45, P=0.12 | R=0.18, P=0.55 | R=0.57, P=0.06 |

| Plasma IL-10 (N=13, 12) | R=0.84, P=0.0007 | R=0.79, P=0.002 | R=0.47, P=0.13 |

| Activated blood CD4 T cells | R=0.30, P=0.26 | R=0.29, P=0.27 | R=0.07, P=0.77 |

| Activated blood CD8 T cells | R=0.48, P=0.06 | R=0.46, P=0.08 | R=0.05, P=0.85 |

| Plasma sCD27 | R=0.32, P=0.23 | R=0.31, P=0.25 | R=0.24, P=0.36 |

| Plasma sCD14 (N=14, 14) | R=0.71, P=0.006 | R=0.39, P=0.17 | R=0.32, P=0.26 |

| Plasma LPS (N=15, 15) | R=0.43, P=0.11 | R=0.29, P=0.29 | R=0.27, P=0.33 |

| Plasma LTA (N=14, 14) | R=0.10, P=0.74 | R=−0.21, P=0.47 | R=0.13, P=0.66 |

| Plasma iFABP | R=−0.56, P=0.03 | R=−0.45, P=0.08 | R=−0.31, P=0.23 |

| Colonic immunity parameters | |||

| HIV-1 RNA levels | R=0.60, P=0.02 | R=0.54, P=0.03 | R=0.53, P=0.03 |

| No. of CD1c+ mDC (N=14, 16) |

R=−0.38, P=0.19 | R=−0.28, P=0.33 | R=−0.47, P=0.07 |

| No. of pDC (N=14, 16) | R=0.38, P=0.16 | R=0.44, P=0.10 | R=0.18, P=0.51 |

| CD1c+ mDC: CD40e (N=14, 16) | R=0.68, P=0.009 | R=0.83, P=0.0005 | R=0.46, P=0.07 |

| pDC CD40 (N=14, 15) | R=−0.06, P=0.84 | R=0.17, P=0.56 | R=−0.15, P=0.59 |

| CD1c+ mDC: CD83f

(N=14, 16) |

R=0.14, P=0.64 | R=0.24, P=0.40 | R=0.14, P=0.61 |

| pDC: CD83 (n=15, 16) | R=0.17, P=0.55 | R=0.22, P=0.41 | R=−0.17, P=0.53 |

| No. of CD4 T cellsg | R=0.03, P=0.92 | R=0.20, P=0.45 | R=0.05, P=0.86 |

| No. of CD8 T cells | R=0.22, P=0.41 | R=0.02, P=0.93 | R=0.10, P=0.72 |

| No. of activated CD4 T cells | R=0.29, P=0.28 | R=0.21, P=0.44 | R=0.27, P=0.31 |

| No. of activated CD8 T cells | R=0.52, P=0.04 | R=0.42, P=0.11 | R=0.42, P=0.09 |

| No. of IFNγ+ CD4 T cells (N=15, 16) |

R=0.05, P=0.87 | R=−0.05, P=0.86 | R=0.05, P=0.87 |

| No. of IL-17+ CD4 T cells (N=15, 16) |

R=0.17, P=0.55 | R=0.10, P=0.73 | R=0.24, P=0.37 |

| No. of IL-22+ CD4 T cells (N=15, 16) |

R=−0.02, P=0.94 | R=0.07, P=0.81 | R=0.09, P=0.74 |

| No. of IFNγ+ CD8 T cells (N=15, 16) |

R=−0.26, P=0.34 | R=−0.13, P=0.64 | R=−0.26, P=0.33 |

| IL-12p70h (N=13, 13) | R=0.64, P=0.02 | R=0.65, P=0.02 | R=0.35, P=0.24 |

| IL-23 (N=13, 13) | R=0.42, P=0.16 | R=0.46, P=0.12 | R=0.18, P=0.57 |

| IL-10 (N=13, 13) | R=0.44, P=0.14 | R=0.45, P=0.13 | R=0.19, P=0.54 |

| IL-1β (N=13, 13) | R=0.37, P=0.22 | R=0.35, P=0.24 | R=0.15, P=0.62 |

| TNFα (N=13, 13) | R=0.29, P=0.33 | R=0.30, P=0.32 | R=0.08, P=0.80 |

| IL-6 (N=13, 13) | R=0.40, P=0.18 | R=0.35, P=0.24 | R=0.25, P=0.42 |

| IFNγ (N=13, 13) | R=0.31, P=0.30 | R=0.32, P=0.28 | R=0.04, P=0.89 |

| IL-17 (N=13, 13) | R=0.29, P=0.34 | R=0.25, P=0.41 | R=0.10, P=0.74 |

Statistical analysis performed using the Spearman test.

Bold font indicates statistically significant correlation.

Outlier identified using Rout test was not included in analyses.

N denotes when not all study participants with tetherin/APOBEC3G or MX2

measurements had immunological data.

CD40 expression levels.

Percent of CD83.

No.: number per gram.

Constitutive production.

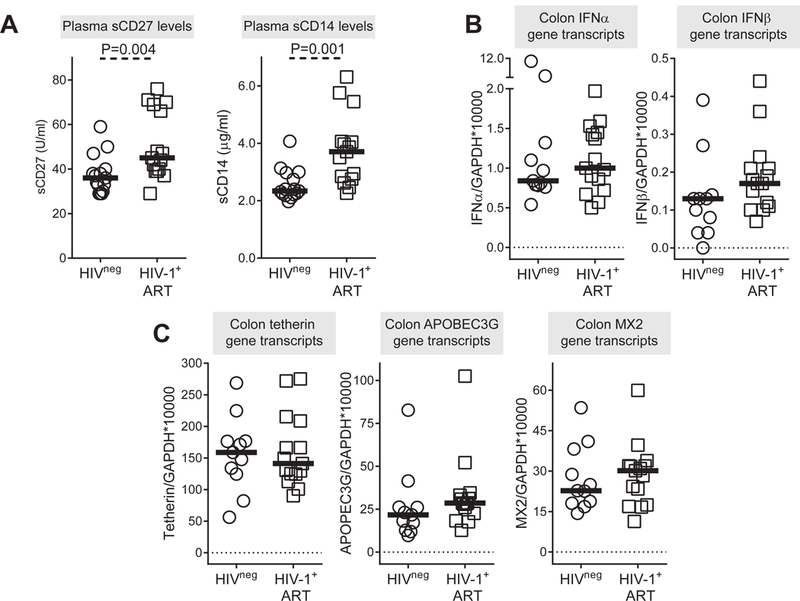

Colon expression of IFN-Is and restriction factors in ART-treated HIV-1 infected subjects were not significantly altered relative to uninfected controls.

The elevated IFN-I signature in the gut during chronic HIV-1 infection may be driven by persistent HIV-1 viremia and/or microbial translocation. To address if these parameters are responsible, we evaluated the levels of IFN-Is and antiretroviral ISGs in a separate cohort of ART-treated HIV-1 infected persons with effective viral suppression (n=15) and age, sex and ethnicity-matched uninfected persons (n=15). Stored plasma and colon biopsies were obtained from the RUMC IRB gastrointestinal repository (S2 Table). Of note, these subjects differed in age and ethnicity compared to those from UC-AMC (compare S1 and S2 Tables). ART-treated HIV-1 infected persons achieved plasma virus suppression (<40 HIV-1 RNA copies/ml) with 508 (range: 178–1415) CD4 cells/μl. CD4 counts were not measured in the uninfected study participants.

Plasma levels of sCD27 and sCD14 were significantly higher in the ART-treated study participants versus uninfected controls (Figure 4A) indicating ongoing lymphocyte and monocyte activation in these individuals despite virological suppression. Colonic gene transcripts levels of both IFNα and IFNβ were not significantly different in HIV-1 infected versus uninfected controls although a trend towards higher numbers of IFNβ transcripts was observed in HIV-1 infected persons (P=0.09) (Figure 4B; S3 Table). IFNα and IFNβ transcripts did not significantly associate with CD4 counts (IFNα: R=0.39, P=0.16; IFNβ: R=−0.06, P=0.84). Similarly, levels of colon tetherin, APOBEC3G and MX2 gene transcripts were not statistically different between the two cohorts, although both MX2 and APOBEC3G had higher median expression with differences in A3G approaching significance (P=0.07). ISG gene transcripts did not significantly associate with CD4 counts (Tetherin: R=−0.05, P=0.85; APOBEC3G: R=0.35, P=0.20; MX2: R= 0.41, P=0.13).

Figure 4. Restriction factor gene transcript levels in colonic cells in treated, chronically infected HIV-1 and uninfected study participants.

(A) Plasma levels of sCD27 and sCD14 in HIV-1 uninfected (HIVneg; n=15) and anti-retroviral therapy (ART) treated HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+ ART; n=15) study participants. Levels of (B) IFNα/β gene transcripts and (C) tetherin (BST2), APOBEC3G and MX2 gene transcripts measured in colonic tissue samples from HIV-1 uninfected (HIVneg; n=11) and ART treated HIV-1 infected (HIV-1+ ART; n=15) study participants. Lines represent median values. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test to determine differences between unmatched groups.

DISCUSSION

The dual nature of the IFN-I response against persistent virus infections complicates strategies to harness the IFN-I pathway to curb viremia and pathogenesis. Efforts to use IFNα to reduce the latent HIV-1 reservoir, or to block IFN-I signaling to reduce inflammation, may need to account for mechanisms that drive the pleiotropic effects of these cytokines. Here, we investigated how levels of diverse IFN-I species (12 IFNα subtypes and IFNβ) and antiviral ISGs in the blood versus the gut correlate with markers of inflammation, microbial translocation and immune activation during chronic untreated HIV-1 infection. We confirm data from other groups [23] that in PBMCs and plasma, IFNα is upregulated, whereas IFNβ is barely detectable. We extend these results to show that the increased IFNα response in the periphery is comprised of IFNα1, IFNα2, IFNα4, IFNα5 and IFNα8. With the exception of IFNα4, these IFNα subtypes were highly expressed in primary pDCs exposed to HIV-1 in our previous study [39]. It remains to be determined if pDCs drive the persistently high IFNα levels in the periphery [23, 61]. Of note, IFNα1, IFNα2 and IFNα5 have the weakest inhibitory activity against HIV-1 [39], suggesting that the chronic IFN-I response in the periphery may not be optimal for HIV-1 control. The immunomodulatory properties of these IFNα subtypes remain to be investigated.

The IFNα subtype profiles we obtained in the blood were not observed in the gut during chronic untreated HIV-1 infection. All IFNα subtypes were downregulated compared to uninfected controls. This finding was surprising, as colonic pDCs were found at higher frequencies in these same HIV-1 infected study participants [57]. We hypothesize that these gut pDCs may be exhausted and/or refractory to IFN-I stimulation during chronic HIV-1 infection [62]. Interestingly, IFNβ was significantly upregulated during chronic HIV-1 infection relative to uninfected controls. The cellular source(s) and stimuli driving IFNβ remain to be determined. We speculate that translocating bacteria may be one contributor [55]. Several reports suggested that IFNβ may have distinct biological effects [40–43]. Current strategies to reduce inflammation aim to completely block IFNAR signaling that may render the host more susceptible to other viral infections. Specifically blocking IFNβ in the gut to diminish immune activation may help maintain some level of innate immunity, as IFNα is still present, albeit at reduced levels. In fact, selective blockade of IFNβ, but not IFNα, in mouse LCMV infection decreased viral persistence and immunopathology [41]. However, in our study, IFNβ was associated with higher numbers of IFNγ and IL17 expressing CD4+ T cells, suggesting a link between IFNβ and gut CD4+ T cell survival. IFNβ may also have direct antibacterial properties [63]. Further studies would be required to test the impact of IFNβ on the gut microbiome and the clinical consequences of IFNβ blockade in the gut.

A recent study showed that IFNβ may select for transmitted/founder HIV-1 strains [18], which comprise the earliest HIV-1 strains in infected individuals. The source of these transmitted/founder strains remains unclear, as IFNβ resistant HIV-1 strains were not readily detected in the plasma of the chronic HIV-1-infected donors using limiting dilution approaches. Since plasma virus likely originates from secondary lymphoid tissues and not from the gastrointestinal tract [64–66], we speculate that the gut may serve as an important reservoir of IFNβ-resistant HIV-1 strains that may be more fit to establish new infections. Cataloguing the IFN-I resistance profiles of systemic versus gut-derived HIV-1 strains should help test this interesting hypothesis.

Consistent with the high levels of IFNβ in the gut, we also observed elevated ISG expression in the gut during chronic HIV-1 infection. However, we found no correlation between IFNβ and ISG expression levels. This lack of correlation may be due to the nonconcurrent kinetics of IFN-I expression and ISG induction [67]. The increased expression of restriction factor ISGs in the gut would theoretically lead to a reduction in gut HIV-1 replication and its associated downstream pathological consequences. Instead, we observed that antiretroviral ISG levels positively correlated with colonic mucosal HIV-1 RNA levels and markers of immune activation and inflammation. Positive correlations were also reported between ISGs in PBMCs and plasma viral load by other groups [8, 10, 21, 22, 24, 25, 68]. Our findings strengthen the notion that during chronic HIV-1 infection, gut IFN-I responses are associated with immunopathogenesis. It remains unknown why the induction of restriction factors does not result in reduced viral loads during chronic infection. We previously reported that microbial exposure of LPMCs ex vivo induces gut CD4+ T cell activation, proliferation and Th17 differentiation, all of which promote HIV-1 susceptibility [51, 52, 55]. Thus, the threshold for restriction factors to inhibit HIV-1 replication in the gut may have been raised in the context of microbial exposure.

We previously showed that microbes can stimulate IFN-I responses in gut lymphocytes ex vivo [55]. However, the extent to which enteric bacteria – and potentially the bacteriophages they harbor (the ‘virome’) [69] – contribute to the elevated IFN-I response in the gut remains unclear. We thus analyzed IFN-I and ISG levels in gut biopsies from a separate cohort of ART-treated, HIV-1-infected versus HIV-1-uninfected individuals. ART-suppressed individuals still had significant microbial translocation and lymphocyte activation relative to uninfected individuals, but ISG levels almost normalized, suggesting that HIV-1 replication, and not microbial translocation, is the primary driver of high IFNβ and ISG expression in the gut. However, a limitation of this study is that colonic tissue HIV-1 RNA levels were not measured in the ART-treated cohort. Of note, prior IFN-I signaling may render cells more refractory to additional IFN-I stimulation [16]. If the gut has been exposed to IFN-Is from migrating pDCs prior to barrier dysfunction, then microbial translocation may not synergistically increase ISG levels. The absence of a strong IFN-I response in suppressed HIV-1 infection relative to untreated HIV-1 infection raises questions as to whether the IFN-I signaling program has been ‘reset’, such that exogenous IFN-Is would now elicit a strong antiviral program to reduce the gut latent HIV-1 reservoir. However, trends for higher ISGs such as Mx2 and APOBEC3G expression in treated HIV-1 infection compared to uninfected controls were still detected. It remains to be determined whether these low-level IFN-I responses still have immunomodulatory effects [34, 35].

There are a several limitations to this exploratory study. To assess the role of HIV-1 replication in driving the colonic IFN-I signature, we obtained colonic biopsies from ART-treated HIV-1 infected and from HIV-1 uninfected persons through a tissue repository at RUMC. These two cohorts were matched for age, gender and ethnicity, but age and ethnicity differed between the RUMC cohorts and the UC-AMC cohorts. Furthermore, previously obtained measurements of mucosal immune activation and inflammation and colonic mucosa HIV-1 RNA levels were only available for the untreated HIV-1 infected cohort. This prevented direct assessment of the relationship between ISGs and indicators of mucosal immunity and tissue HIV-1 replication in the ART-treated cohort. Sexual practice has recently been reported to impact the intestinal microbiome and has also been linked to mucosal immune cell activation and inflammation independent of HIV-1 [70, 71]. However, recruitment of study participants for this current study did not control for sexual practice. In addition, this study was not powered to investigate IFN-I gene expression and corrections for multiple comparisons have not been undertaken. Thus, the direct associations between ISGs and virological and immunological parameters observed in this current study must be interpreted with some caution. Nevertheless, our findings should inform the design of larger, statistically-powered studies on the relationship between colonic IFN-I responses pre and post-ART (ideally in the same individuals), colonic tissue HIV-1 RNA levels and indicators of immune activation while controlling for sexual practice, age, gender and ethnicity.

To conclude, we provide evidence for a compartmentalized IFN-I response during chronic HIV-1 infection in the gut, with a predominant IFNβ response and high ISG levels that correlated with immune activation, microbial translocation and inflammation. HIV-1 replication is a major driver of the ISG response in the gut, as ART significantly reduces this response. These data may help direct strategies to harness the IFN-I pathway to reduce chronic HIV-1 immune activation that is initiated and maintained in the gastrointestinal tract.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge all the clinical study participants as well as the physicians and staff at the University of Colorado Infectious Disease Group Practice Clinic and Rush University Medical Center Section of Gastroenterology as well both University Hospital endoscopy clinics for their assistance with our clinical study. We thank Eric Lee and Andrew Donovan, Department of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus for technical assistance with the generation of data associated with our previous clinical study.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK088663 (CCW), R01 AI134220 (CCW and MLS) and the University of Colorado RNA Bioscience Institute (MLS and CCW). This work was performed with the support of the Translational Virology Core at the San Diego Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI036214).

Footnotes

Author contributions: SMD, KG performed laboratory experiments and data analysis; SMD, CCW, MLS participated in study design, data analysis and wrote the primary version of the article; GA performed endoscopies; SG and ALL assisted with clinical study assays; EAM, JL, GS and AK participated in study design, enrolled study participants and performed endoscopic procedures as part of the RUMC gastrointestinal repository. PAE PC and AL participated in study design, collected clinical data and coordinated sample inventories at RUMC. All authors participated in revisions of the article.

DISCLAIMERS: The authors have no disclaimers.

REFERENCES

- 1.McNab F, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, Wack A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in infectious disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 2015; 15(2):87–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odorizzi PM, Wherry EJ. Immunology. An interferon paradox. Science 2013; 340(6129):155–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snell LM, McGaha TL, Brooks DG. Type I Interferon in Chronic Virus Infection and Cancer. Trends in Immunology 2017; 38(8):542–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Utay NS, Douek DC. Interferons and HIV Infection: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Pathog Immun 2016; 1(1):107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meager A The Interferons: characterization and application. Wiley-VCH; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris LD, Tabb B, Sodora DL, Paiardini M, Klatt NR, Douek DC, et al. Downregulation of robust acute type I interferon responses distinguishes nonpathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of natural hosts from pathogenic SIV infection of rhesus macaques. Journal of Virology 2010; 84(15):7886–7891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stacey AR, Norris PJ, Qin L, Haygreen EA, Taylor E, Heitman J, et al. Induction of a striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infections. Journal of Virology 2009; 83(8):3719–3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraietta JA, Mueller YM, Yang G, Boesteanu AC, Gracias DT, Do DH, et al. Type I interferon upregulates Bak and contributes to T cell loss during human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. PLoS Pathogens 2013; 9(10):e1003658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.George J, Renn L, Verthelyi D, Roederer M, Rabin RL, Mattapallil JJ. Early treatment with reverse transcriptase inhibitors significantly suppresses peak plasma IFNalpha in vivo during acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Cellular Immunology 2016; 310:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyrcza MD, Kovacs C, Loutfy M, Halpenny R, Heisler L, Yang S, et al. Distinct transcriptional profiles in ex vivo CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are established early in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection and are characterized by a chronic interferon response as well as extensive transcriptional changes in CD8+ T cells. Journal of Virology 2007; 81(7):3477–3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiao Y, Zhang T, Wang R, Zhang H, Huang X, Yin J, et al. Plasma IP-10 is associated with rapid disease progression in early HIV-1 infection. Viral Immunol 2012; 25(4):333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Smith AJ, Schacker TW, Carlis JV, Duan L, Reilly CS, et al. Microarray analysis of lymphatic tissue reveals stage-specific, gene expression signatures in HIV-1 infection. J Immunol 2009; 183(3):1975–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simmons RP, Scully EP, Groden EE, Arnold KB, Chang JJ, Lane K, et al. HIV-1 infection induces strong production of IP-10 through TLR7/9-dependent pathways. AIDS 2013; 27(16):2505–2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harper MS, Barrett BS, Smith DS, Li SX, Gibbert K, Dittmer U, et al. IFN-alpha treatment inhibits acute Friend retrovirus replication primarily through the antiviral effector molecule Apobec3. J Immunol 2013; 190(4):1583–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberatore RA, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin is a key effector of the antiretroviral activity of type I interferon in vitro and in vivo. PNAS 2011; 108(44):18097–18101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandler NG, Bosinger SE, Estes JD, Zhu RT, Tharp GK, Boritz E, et al. Type I interferon responses in rhesus macaques prevent SIV infection and slow disease progression. Nature 2014; 511(7511):601–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster TL, Wilson H, Iyer SS, Coss K, Doores K, Smith S, et al. Resistance of Transmitted Founder HIV-1 to IFITM-Mediated Restriction. Cell Host & Microbe 2016; 20(4):429–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iyer SS, Bibollet-Ruche F, Sherrill-Mix S, Learn GH, Plenderleith L, Smith AG, et al. Resistance to type 1 interferons is a major determinant of HIV-1 transmission fitness. PNAS 2017; 114(4):E590–E599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Pan Q, Liang Z, Qiao W, Cen S, Liang C. The highly polymorphic cyclophilin A-binding loop in HIV-1 capsid modulates viral resistance to MxB. Retrovirology 2015; 12:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Acchioni C, Marsili G, Perrotti E, Remoli AL, Sgarbanti M, Battistini A. Type I IFN--a blunt spear in fighting HIV-1 infection. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2015; 26(2):143–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Mohsen M, Raposo RA, Deng X, Li M, Liegler T, Sinclair E, et al. Expression profile of host restriction factors in HIV-1 elite controllers. Retrovirology 2013; 10:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang JJ, Woods M, Lindsay RJ, Doyle EH, Griesbeck M, Chan ES, et al. Higher expression of several interferon-stimulated genes in HIV-1-infected females after adjusting for the level of viral replication. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2013; 208(5):830–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardy GA, Sieg S, Rodriguez B, Anthony D, Asaad R, Jiang W, et al. Interferon-alpha is the primary plasma type-I IFN in HIV-1 infection and correlates with immune activation and disease markers. PloS One 2013; 8(2):e56527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotger M, Dang KK, Fellay J, Heinzen EL, Feng S, Descombes P, et al. Genome-wide mRNA expression correlates of viral control in CD4+ T-cells from HIV-1-infected individuals. PLoS Pathogens 2010; 6(2):e1000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sedaghat AR, German J, Teslovich TM, Cofrancesco J, Jr., Jie CC, Talbot CC, Jr., et al. Chronic CD4+ T-cell activation and depletion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: type I interferon-mediated disruption of T-cell dynamics. Journal of Virology 2008; 82(4):1870–1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stylianou E, Aukrust P, Bendtzen K, Muller F, Froland SS. Interferons and interferon (IFN)-inducible protein 10 during highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART)-possible immunosuppressive role of IFN-alpha in HIV infection. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2000; 119(3):479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Sydow M, Sonnerborg A, Gaines H, Strannegard O. Interferon-alpha and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in serum of patients in various stages of HIV-1 infection. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 1991; 7(4):375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu JW, Liu FL, Mu D, Deng DY, Zheng YT. Increased expression and dysregulated association of restriction factors and type I interferon in HIV, HCV mono- and co-infected patients. Journal of Medical Virology 2016; 88(6):987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosinger SE, Li Q, Gordon SN, Klatt NR, Duan L, Xu L, et al. Global genomic analysis reveals rapid control of a robust innate response in SIV-infected sooty mangabeys. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009; 119(12):3556–3572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deeks SG, Tracy R, Douek DC. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity 2013; 39(4):633–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunt PW. HIV and inflammation: mechanisms and consequences. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 2012; 9(2):139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klatt NR, Chomont N, Douek DC, Deeks SG. Immune activation and HIV persistence: implications for curative approaches to HIV infection. Immunological Reviews 2013; 254(1):326–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klatt NR, Funderburg NT, Brenchley JM. Microbial translocation, immune activation, and HIV disease. Trends in Microbiology 2013; 21(1):6–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng L, Ma J, Li J, Li D, Li G, Li F, et al. Blocking type I interferon signaling enhances T cell recovery and reduces HIV-1 reservoirs. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017; 127(1):269–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhen A, Rezek V, Youn C, Lam B, Chang N, Rick J, et al. Targeting type I interferon-mediated activation restores immune function in chronic HIV infection. The Journal of ClinicalInvestigation 2017; 127(1):260–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cha L, de Jong E, French MA, Fernandez S. IFN-alpha exerts opposing effects on activation-induced and IL-7-induced proliferation of T cells that may impair homeostatic maintenance of CD4+ T cell numbers in treated HIV infection. J Immunol 2014; 193(5):2178–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ries M, Pritschet K, Schmidt B. Blocking type I interferon production: a new therapeutic option to reduce the HIV-1-induced immune activation. Clinical & Developmental Immunology 2012; 2012:534929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nature Immunology 2004; 5(12):1219–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper MS, Guo K, Gibbert K, Lee EJ, Dillon SM, Barrett BS, et al. Interferon-alpha Subtypes in an Ex Vivo Model of Acute HIV-1 Infection: Expression, Potency and Effector Mechanisms. PLoS Pathogens 2015; 11(11):e1005254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaitin DA, Roisman LC, Jaks E, Gavutis M, Piehler J, Van der Heyden J, et al. Inquiring into the differential action of interferons (IFNs): an IFN-alpha2 mutant with enhanced affinity to IFNAR1 is functionally similar to IFN-beta. Mol Cell Biol 2006; 26(5):1888–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng CT, Sullivan BM, Teijaro JR, Lee AM, Welch M, Rice S, et al. Blockade of interferon Beta, but not interferon alpha, signaling controls persistent viral infection. Cell Host & Microbe 2015; 17(5):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Runkel L, Pfeffer L, Lewerenz M, Monneron D, Yang CH, Murti A, et al. Differences in activity between alpha and beta type I interferons explored by mutational analysis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998; 273(14):8003–8008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheehan KC, Lazear HM, Diamond MS, Schreiber RD. Selective Blockade of Interferon-alpha and -beta Reveals Their Non-Redundant Functions in a Mouse Model of West Nile Virus Infection. PloS One 2015; 10(5):e0128636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zaritsky LA, Dery A, Leong WY, Gama L, Clements JE. Tissue-specific interferon alpha subtype response to SIV infection in brain, spleen, and lung. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine research 2013; 33(1):24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwa S, Kannanganat S, Nigam P, Siddiqui M, Shetty RD, Armstrong W, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are recruited to the colorectum and contribute to immune activation during pathogenic SIV infection in rhesus macaques. Blood 2011; 118(10):2763–2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lehmann C, Jung N, Forster K, Koch N, Leifeld L, Fischer J, et al. Longitudinal analysis of distribution and function of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in peripheral blood and gut mucosa of HIV infected patients. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2014; 209(6):940–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brenchley JM, Douek DC. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annual Review of Immunology 2012; 30:149–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ancuta P, Kamat A, Kunstman KJ, Kim EY, Autissier P, Wurcel A, et al. Microbial translocation is associated with increased monocyte activation and dementia in AIDS patients. PloS One 2008; 3(6):e2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, Asher TE, Silvestri G, Rao S, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nature Medicine 2006; 12(12):1365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchetti G, Tincati C, Silvestri G. Microbial translocation in the pathogenesis of HIV infection and AIDS. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2013; 26(1):2–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dillon SM, Lee EJ, Donovan AM, Guo K, Harper MS, Frank DN, et al. Enhancement of HIV-1 infection and intestinal CD4+ T cell depletion ex vivo by gut microbes altered during chronic HIV-1 infection. Retrovirology 2016; 13:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dillon SM, Manuzak JA, Leone AK, Lee EJ, Rogers LM, McCarter MD, et al. HIV-1 infection of human intestinal lamina propria CD4+ T cells in vitro is enhanced by exposure to commensal Escherichia coli. J Immunol 2012; 189(2):885–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steele AK, Lee EJ, Manuzak JA, Dillon SM, Beckham JD, McCarter MD, et al. Microbial exposure alters HIV-1-induced mucosal CD4+ T cell death pathways Ex vivo. Retrovirology 2014; 11:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dillon SM, Frank DN, Wilson CC. The gut microbiome and HIV-1 pathogenesis: a two-way street. AIDS 2016; 30(18):2737–2751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoder AC, Guo K, Dillon SM, Phang T, Lee EJ, Harper MS, et al. The transcriptome of HIV-1 infected intestinal CD4+ T cells exposed to enteric bacteria. PLoS Pathogens 2017; 13(2):e1006226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dillon SM, Lee EJ, Kotter CV, Austin GL, Dong Z, Hecht DK, et al. An altered intestinal mucosal microbiome in HIV-1 infection is associated with mucosal and systemic immune activation and endotoxemia. Mucosal Immunology 2014; 7(4):983–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dillon SM, Lee EJ, Kotter CV, Austin GL, Gianella S, Siewe B, et al. Gut dendritic cell activation links an altered colonic microbiome to mucosal and systemic T-cell activation in untreated HIV-1 infection. Mucosal Immunology 2016; 9(1):24–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dillon SM, Castleman MJ, Frank DN, Austin GL, Gianella S, Cogswell AC, et al. Inflammatory colonic innate lymphoid cells are increased during untreated hiv-1 infection and associated with markers of gut dysbiosis and mucosal immune activation. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dillon SM, Kibbie J, Lee EJ, Guo K, Santiago ML, Austin GL, et al. Low abundance of colonic butyrate-producing bacteria in HIV infection is associated with microbial translocation and immune activation. AIDS 2017; 31(4):511–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Colomer-Lluch M, Gollahon LS, Serra-Moreno R. Anti-HIV Factors: Targeting Each Step of HIV’s Replication Cycle. Current HIV Research 2016; 14(3):175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dillon SM, Robertson KB, Pan SC, Mawhinney S, Meditz AL, Folkvord JM, et al. Plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells with a partial activation phenotype accumulate in lymphoid tissue during asymptomatic chronic HIV-1 infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 48(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zuniga EI, Liou LY, Mack L, Mendoza M, Oldstone MB. Persistent virus infection inhibits type I interferon production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells to facilitate opportunistic infections. Cell Host & Microbe 2008; 4(4):374–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kaplan A, Lee MW, Wolf AJ, Limon JJ, Becker CA, Ding M, et al. Direct Antimicrobial Activity of IFN-beta. J Immunol 2017; 198(10):4036–4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Josefsson L, Palmer S, Faria NR, Lemey P, Casazza J, Ambrozak D, et al. Single cell analysis of lymph node tissue from HIV-1 infected patients reveals that the majority of CD4+ T-cells contain one HIV-1 DNA molecule. PLoS Pathogens 2013; 9(6):e1003432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lerner P, Guadalupe M, Donovan R, Hung J, Flamm J, Prindiville T, et al. The gut mucosal viral reservoir in HIV-infected patients is not the major source of rebound plasma viremia following interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Journal of Virology 2011; 85(10):4772–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Petravic J, Vanderford TH, Silvestri G, Davenport M. Estimating the contribution of the gut to plasma viral load in earlySIV infection. Retrovirology 2013; 10:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson EB, Yamada DH, Elsaesser H, Herskovitz J, Deng J, Cheng G, et al. Blockade of chronic type I interferon signaling to control persistent LCMV infection. Science 2013; 340(6129):202–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scagnolari C, Monteleone K, Selvaggi C, Pierangeli A, D’Ettorre G, Mezzaroma I, et al. ISG15 expression correlates with HIV-1 viral load and with factors regulating T cell response. Immunobiology 2016; 221(2):282–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Monaco CL, Gootenberg DB, Zhao G, Handley SA, Ghebremichael MS, Lim ES, et al. Altered Virome and Bacterial Microbiome in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Cell Host & Microbe 2016; 19(3):311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelley CF, Kraft CS, de Man TJ, Duphare C, Lee HW, Yang J, et al. The rectal mucosa and condomless receptive anal intercourse in HIV-negative MSM: implications for HIV transmission and prevention. Mucosal Immunology 2017; 10(4):996–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noguera-Julian M, Rocafort M, Guillén Y, Rivera J, Casadellà M, Nowak P, et al. Gut Microbiota Linked to Sexual Preference and HIV Infection. EBioMedicine 2016; 5:135–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.