Abstract

Engaging patients and communities is invaluable for achieving a patient‐centered learning health system. Based on lessons learned in genomic and public health public engagement efforts of our community‐based organizations in Flint, Michigan, we offer a continuum model for distinguishing various levels of community engagement and recommendations for approaching community, patient, and public engagement for health care systems that are expanding uses of health information.

Keywords: Community engagement, learning health system, patient‐centered health care, public engagement, quality improvement, trust

1. INTRODUCTION

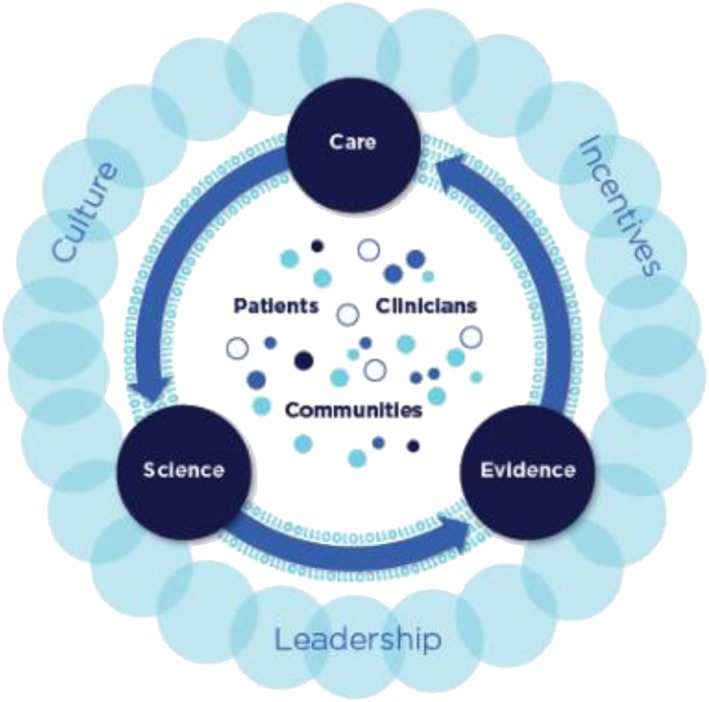

Engaging patients and communities is invaluable for achieving a patient‐centered learning health system. The Institute of Medicine 2012 report, Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America, defines a learning health system (LHS) as a system “designed to generate and apply the best evidence for the collaborative health care choices of each patient and provider; to drive the process of discovery as a natural outgrowth of patient care; and to ensure innovation, quality, safety, and value in health care.”1 Learning health system core values were developed to present a gold standard approach toward the mission of a national patient‐centered LHS.2 One core value is cooperative and participatory leadership, which ensures the participation/engagement of diverse communities and populations.3 As LHS frameworks increasingly shape health information use in a variety of ways ranging from research to large‐scale quality improvement and to chronic disease management, there are abundant opportunities and challenges for engagement. A critical factor in a productive LHS is the engagement of patients, family members, and community.3 The National Academy of Medicine posits engaged and empowered patients as a key characteristic of the LHS.4 Understanding the optimal strategies for knowing when, how, and to what extent to engage the public will be critical to building meaningful relationships between health care systems and the communities they aim to serve. Notably, an important consideration is the cultural context within which these processes occur (Figure 1) as supported by the Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Medicine's table of characteristics of a LHS. It is also important to have a clear definition of “community” and shared definitions across communities that enable dialogue about the goals and activities of efforts, such as LHSs, to improve health for all. In this paper, we draw on lessons learned from decades of community‐engaged health research and practice locally, in Flint, Michigan, in the Midwest Region, and at the national level addressing issues related to genomics.

Figure 1.

Schematic of a learning health care system

Our work to inform, educate, consult with, and assess the needs of communities following the successful completion of the Human Genome Project, for example, illuminated the need to appropriately consider culture and cultural contexts. With Flint Community Based Organization Partners, we partnered with the National Community Committee of the CDC's Prevention Research Centers on the “Genomics, Community and Equity” project to implement a community‐based participatory research model of achieving community engagement in genomics, hosting discussions for the Midwest region that elucidated community perspectives on ethical, social, and legal implications around genetics research. This, along with other initiatives such as the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health who strongly emphasize and puts high priority on partner engagement, 4 led us to ask how lessons from these engagements could be translated into opportunities for community engagement in an LHS. We believe it is critical that all players within the health system are engaged to their full potential to optimize the learning opportunities within a health system. We offer a continuum model for distinguishing various levels of engagement that link communities with health systems and research and make recommendations for achieving sustainable community engagement in the emerging LHS. This perspective was shared during the symposium held at the University of Michigan in 2016 on the Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications of Learning Health Systems.

2. WHY COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT IN A LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM?

The literature supports that patient engagement has positively impacted the health system in many domains such as overall health outcomes, clinical outcomes, patient adherence, employee satisfaction, reduced malpractice risk, and greater financial performance,5, 6, 7 which suggests that LHSs will benefit from community engagement strategies. To understand the role of community engagement in an LHS, consider the case where full community engagement exists (ie, the community both providing and receiving service) at all levels of patient interaction. What would that LHS look like? What kind of knowledge would that LHS generate? Wherever a patient, family member, or caregiver interacts constitutes a point of engagement within the LHS. Patient/community–initiated methods of data collection, social networking, and information sharing provide positive outcomes for a LHS. This type of engagement may yield improved health system performance, patient adherence, and financial and clinical performance.8 More importantly, the knowledge gained generates a feedback loop of continuous learning within the LHS. Thus, at the far end of the spectrum, a fully engaged community is involved in all phases of the learning health cycle since such engagement will enhance the systems' capacity for knowledge generation.

Community‐engaged research can also benefit an LHS. Research questions, approaches, and specific learning objectives become more relevant and meaningful when the community is engaged in the research process. This may result in an enhanced system design and delivery model that is culturally informed and culturally appropriate for the stakeholders within the community and the LHS. Furthermore, this builds capacity among providers and receivers in the community, increasing the likelihood that results and knowledge gained from research is translated and disseminated effectively and equitably to all stakeholders. The Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute supports the belief that the engagement of patients, family members, caregivers, and other stakeholders is a means to improve and positively impact both health outcomes and clinical decision making. Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute has created an engagement rubric that highlights the various ways to utilize patient/community engagement in research.9 It is this type of engagement, engagement by all stakeholders, that may foster a shared commitment that leads to effective program implementation and continuous learning across a health care system.

3. DEFINING “COMMUNITY” AND “COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT” IN AN LHS

“Community” can be narrowly or broadly defined. Webster dictionary defines community as people with common interests living in a common area.10 In a broader sense, community could be where one lives, works, plays, and worships collectively with others, as well as community organizations, institutions, and community centers and thus may play critical roles as stakeholders to the plethora of services that resident receive. Engagement of community at the organizational and institutional levels are key elements to community engagement. One way to define “community” is to identify the stakeholders one intends to engage. In this conversation, we defined our community as those working within and utilizing services of the LHS. Stakeholders within the LHS are critical to the knowledge that the health system produces11 and may include researchers, clinicians, insurance providers, and other key staff embedded in the system. Each one is part of the community within the LHS who facilitates and provides health services; we will call them providers in that they provide some service within the health system to the patient/community. In addition, patients, patient advocates, family members, and caregivers are community stakeholders who can be viewed as receivers of services within the health system, with complementary roles within the LHS12; we will call them receivers. In an effort to effectively maximize the full benefit of an LHS, providers and receivers must be actively engaged. In an ideally engaged LHS, the receivers (patients, family, and community stakeholders) will through their interactions become empowered to provide critical feedback to the provider, which could be a nurse or dietician, and that information is then utilized in the continuous quality improvement of the system.

With “community” defined, delineation of “community engagement” becomes easier. The CDC defines community engagement as “the process of working collaboratively with, and through, groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well‐being of those people.”13 Whether the community consists of patients, service providers, families, or community residents, it is important that receivers and providers are engaged in an LHS or research studies collaboratively.

4. A CONTINUUM OF ENGAGEMENT

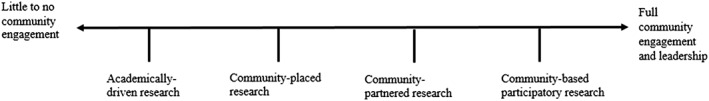

The ability to engage the community that provides the services and the community that receives the service within an LHS may directly affect the quality of the information that may be produced within that system.11 Our model of a community‐engaged research continuum (Figure 2) can be applied to an LHS to delineate approaches to engaging set communities within the system. This continuum covers traditional approaches to engagement, where the community being researched does not have the opportunity to provide any input to guide the research. At the opposite end of the continuum are more participatory models of engagement, with an endpoint where research is initiated by the community.

Figure 2.

Community‐engaged research continuum

In traditional research engagement approaches, the community only receives the service and is not engaged in the research process. In this scenario, the community receiving the service is only informed by the community of providers. The community receiving a service has been granted very little opportunity to provide input for the research questions/learning objectives, designs, or approaches, and the community's role in this scenario is predominantly as the subject or the participant. We have seen this occur when members of the Flint community are asked to respond to surveys and have not been consulted regarding the relevance, design, questions, or recruitment method for the survey. A critical missing component from this point of engagement is the community's input. This input could be vital to the overall outcomes of the survey, as it would respond to the following questions: Are the questions understandable and relevant to the community? Are the issues being surveyed important to the community? Is the language used culturally/linguistically appropriate? These are critical questions the community could address when involved in the earlier stages of the research effort. As a result of this experience in Flint, Michigan, the Flint/Genesee County Speak to Your Health Community Survey, a biennial community‐based survey, was developed by a collaborative partnership consisting of community, academia, and the health department. Survey topics, questions, and recruitment strategies are all decided by the collaborative partnership, creating community “buy in” and equity‐based decision making.14 This experience provides the basis for recommendations for effective community engagement strategies.

As we move across the continuum, we notice the community may become a bit more involved (even though the scenario may still appear to be academically or health system driven). The establishment of community/patient advisory boards serves as a point of engagement designed to give the community a voice to provide input and consult on various issues as they emerge. Even at this level of engagement, the community/patient advisory boards may be limited in their scope of decision making, power, and control. As we move towards a more community‐placed engagement, we find community/patient advisory boards more involved, and the research or LHS project is placed somewhere in the local vicinity of the community where people are engaging within the context of the physical spaces of the community receiving the service.

Next, we have a community‐partnered mode of engagement where community is derived from a partnership between the community and the researcher (the community receiving the service and the community providing the service) has moved the research or LHS forward. At this point, the community has input in projects, questions, and learning objectives and may have some input around the design of research and practice. In community partnered engagement, the community may also be involved in other critical phases of the research such as the data analysis and the dissemination and translation of the findings.

Finally, near the end of the continuum there is community‐based participatory mode of engagement where the community is involved in all phases of the process and the community has co‐ownership of the data and products. When communities that receive services are provided control of and access to their community data, it is more likely to advance a receiver‐driven culture of research and continuous improvement.12

5. SHARED MEANING AND TRUST ACROSS THE CONTINUUM

Each mode of community engagement across the continuum represents a process that requires shared language and meaning as well as trust. With respect to language, words can have different definitions based on context and discipline. While serving as the Executive Director of the Universal Kidney Foundation and engaging health care providers about developing community partnerships, Ms Lewis (co‐author) encountered complexity and discontinuity while investigating the definition of meaningful use in the context of health care. Meaningful use is known in health policy and IT circles as a set of specific technical requirements for health information reporting to track adoption and implementation of electronic health records. In the vernacular, meaningful use implies just a significance or value to the use of health records to relevant stakeholders. To use the term meaningful use absent from “meaning of use” in patient communities rings hollow. Such terms not only impact public comprehension, but different notions of definitions can greatly influence the ability of providers and recipient community members to engage in partnerships; therefore, efforts should be taken to reduce technical jargon and communicate in terms understood by both receivers and providers.

Trust is a critical factor at each stage of the continuum of community engagement to support a quality LHS. According to the Office of the National Coordinator report, trust is perceived as a barrier, in that there is no reliable systematic method to scale trust across disparate networks, resulting in participants being unwilling to incorporate and use shared data.15 Trust does not just happen; it must be built over time. Trust is necessary. The patient and community must trust that they are being heard by providers, and future stakeholders involved in the care process; that medical records are being utilized safely and securely by providers; and that information is being disseminated appropriately over time. Recognition and trust in this process by both the community and providers will assist in building community capacity and ensure better communication. Understanding this, the Office of the National Coordinator identifies creating a trusted environment for the collecting, sharing, and using of electronic health information as its third critical pathway on the roadmap to interoperability.15 Therefore, this leads to the need for cross‐fertilization, where both the patient and provider communities' capacity is increased to share information.

Bidirectionality is not enough; it is important to be rooted in cross‐fertilization. The team approach should become a part of the culture of care on a regular basis because the system itself, the cart, and the hospital bed are not making a difference. It is the interaction between the patient, the orderly, the folks that fix the food, and those that bring it to the table for people to eat. It is the human interaction that is critical to effectively building a LHS. That trust is so important. We suggest that the quality of information obtained through this process will be improved. Understanding the importance of the process and the value of patient/community will open opportunities for input and improve the feedback loop. These interactions will provide opportunities for adjustments in real time that can improve the quality of the process as well as the outcomes. Consequently, as we continue this “technical journey” as health care professionals, we must all recognize that it is imperative to find the appropriate balance between what is “good for the system” over the long run and what is “operationally achievable” by our existing health care system over the short term.15 And we would add, keeping in mind the importance of human interactions and relationships.

6. RECOMMENDATIONS

When invited to address the topic sustainable community engagement in a constantly changing health system the journey of a life time, years of experience of community engagement and partnership development were employed. Consideration was given to the history of working locally in Flint, Michigan, our regional efforts, as well as national, to address health and health disparities among racial and ethnically diverse populations within communities. How could these experiences inform and support community involvement in an ever‐changing health system? We ultimately determined that the consistent factors that lead to successful engagement and integration should be the focus for our sharing and recommendations.

Integrating a team‐based culture of engagement in the LHS cycle is critical. This will require consideration of how community and community engagement will be defined; clarity of purpose for engaging the community, as well as training and education in foundational skills and approaches to engaging with identified communities.

Therefore, we offer the following recommendations:

explore ways to intentionally integrate the community voice when defining and establishing a LHS;

utilize the concept of community engagement as a continuum;

identify ways to include the patient or the community at every possible level;

inform and advise a patient of their options and opportunities;

provide education and information about the health record and response;

be open to challenging feedback that may inform the process;

identify ways to include the feedback in the ongoing CQI process;

maintain high‐quality engagement throughout the learning health cycle.

Effective communication and trust are essential to achieve sustainable community engagement in a changing health system.

This presentation was the first effort to incorporate lessons learned from our work in Community‐Engaged Research and Community‐Based Participatory Research as well as overall efforts to engage community in understanding health and health care. It is essential to continue to provide community members with information to assist in understanding how best to make informed decisions about their health and health care. As a result, consideration is given exploring additional opportunities/dialogues to expand efforts to assist in addressing barriers identified to increasing community engagement in developing sustainable LHSs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Insights from this presentation were drawn from research and engagements supported by the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (MICHR), grant number UL1TR00043/NIH/NCATS. We thank Nikolas Koscielniak and Tevah Platt for assisting with the proofreading and preparation of this manuscript.

Key KD, Lewis EY. Sustainable community engagement in a constantly changing health system. Learn Health Sys. 2018;2:e10053 10.1002/lrh2.10053

Contributor Information

Kent D. Key, Email: kent.key@hc.msu.edu

E. Yvonne Lewis, Email: eyvonlewis@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brooks D, Douglas M, Aggarwal N, Prabhakaran S, Holden K, Mack D. Developing a framework for integrating health equity into the learning health system. Learning Health Sys. 2017:e10029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Core values underlying a national‐scale person‐centered continuous learning health system (LHS). 2012. Learning Health System Summit. Available at http://www.learninghealth.org/corevalues/.

- 3. Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuous Learning Health Care in America. 2013. Institute of Medicine . National Academies Press. https://www.nap.edu/read/13444/chapter/1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Global Alliance for Genomics and Health . Partner engagement.2017. Available at https://www.ga4gh.org/

- 5. Charmel PA, Frampton SB. Building the business case for patient‐centered care. [internet]. Healthc Financ Manage. 2008;62:80‐85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barry MJ, Edgman‐Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient‐centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780‐781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaller D, Consulting S: Patient‐centered care: what does it take? Dale Shaller Shaller Consulting October 2007 [Internet]. Commonwealthfund 2007;Available from: www.commonwealthfund.org.

- 8. Conway PH, Clancy C. Transformation of health care at the front line. JAMA. 2009;301(7):763‐765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hillard T, Paez K. The PCORI engagement rubric: promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):165‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Merriam Webster's Dictionary . Community defined. Accessed from the world wide web on December 24, 2017 at https://www.merriam‐webster.com/dictionary/community

- 11. Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335(7609):24‐27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, editors, Medicine R on E: the Learning Healthcare System [Internet]. 2007. 10.17226/11903 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Committee C and TSA (CTSA) CCEKF: principles of community engagement. NIH Publ No 11‐7782 2011; http://www.cdc.gov/phppo/pce/.

- 14. Kruger D, Shirey L, Morrels‐Samuels S, Skorcz S, ACHE , Brady J. Using a community‐based health survey as a tool for informing local health policy. J Public Health Manag Pract 2009. 2009;15:47‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) for Health Information Technology . 2014. Connecting health care for the nation: a shared nationwide interoperability roadmap. Retrieved on December 27, 2017 from the World Wide Web at https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/hie‐interoperability/nationwide‐interoperability‐roadmap‐final‐version‐1.0.pdf